Abstract

Objective

Pulmonary nocardiosis frequently develops as an opportunistic infection in patients with malignant tumor and is treated with steroids. This study was performed to clarify the clinical features of pulmonary nocardiosis in Japan.

Methods

The patients definitively diagnosed with pulmonary nocardiosis at our hospital between January 1995 and December 2015 were retrospectively investigated.

Results

Nineteen men and 11 women (30 in total) were diagnosed with pulmonary nocardiosis. Almost all patients were complicated by a non-pulmonary underlying disease, such as malignant tumor or collagen vascular disease, or pulmonary disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or interstitial pneumonia, and 13 patients (43.3%) were treated with steroids or immunosuppressors. Gram staining was performed in 29 patients, and a characteristic Gram-positive rod was detected in 28 patients (96.6%). Thirty-one strains of Nocardia were isolated and identified. Seven strains of Nocardia farcinica were isolated as the most frequent species, followed by Nocardia nova isolated from 6 patients. Seventeen patients died, giving a crude morality rate of 56.7% and a 1-year survival rate of 55.4%. The 1-year survival rates in the groups with and without immunosuppressant agents were 41.7% and 59.7%, respectively, showing that the outcome of those receiving immunosuppressants tended to be poorer than those not receiving them.

Conclusion

Pulmonary nocardiosis developed as an opportunistic infection in most cases. The outcome was relatively poor, with a 1-year survival rate of 55.4%, and it was particularly poor in patients treated with immunosuppressant agents. Pulmonary nocardiosis should always be considered in patients presenting with an opportunistic respiratory infection, and an early diagnosis requires sample collection and Gram staining.

Keywords: Pulmonary nocardiosis, opportunistic infection, Gram-stain

Introduction

Nocardia is an aerobic Gram-positive rod belonging to the Actinomycetales order and is mainly distributed in the soil. While Nocardia infection does occasionally occur in healthy individuals, it more frequently occurs in patients with impaired cellular immunity due to malignant tumor, diabetes mellitus, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome, and steroids and immunosuppressor treatments are known risk factors of this disease (1-14). Pulmonary nocardiosis most frequently develops among Nocardia infections, and the presence of chronic respiratory disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis, is a risk factor of pulmonary nocardiosis (1-14). However, only a few cases of pulmonary nocardiosis have been reported in Japan, and only a few studies involving many patients have been performed (15,16). This study was performed to clarify the clinical features of pulmonary nocardiosis in Japan.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects

Patients diagnosed with pulmonary nocardiosis at our hospital between January 1995 and December 2015 were retrospectively investigated using their medical records. Cases in which Nocardia was isolated by a culture of respiratory samples, such as sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage, pulmonary puncture sample, and pleural effusion, or blood culture with subjective and objective symptoms and laboratory test and imaging findings suggesting respiratory infection were defined as pulmonary nocardiosis. Immunosuppressors, such as steroids and cyclosporine, were simultaneously analyzed as innumosuppressant agents. Cases without symptoms suggesting respiratory infection despite Nocardia being isolated from sputum and those with no new appearance of an abnormal shadow on chest radiography were judged as colonization and excluded from ttanalysis. Eight patients overlapped with those in the previous report (15).

Microbiological identification

In the bacteriological investigation, when a Gram-positive rod was suspected as Nocardia on Gram staining, Kinyoun's stain was additionally performed, followed by culture on blood agar medium. The bacterial species was identified by biochemical identification tests, a 16S-ribosomal RNA base sequence analysis, or mass spectrometry. Regarding drug susceptibility, the minimum growth inhibitory concentration was measured using the broth microdilution method and judged in accordance with CLSI M24-A. When infection with other microorganisms was confirmed within one week before or after the date of the diagnosis of pulmonary nocardiosis, it was judged as a mixed infection.

Statistical analyses

The survival time was defined as the period from the date of the diagnosis of pulmonary nocardiosis to the date of death, and the observation of survivors was discontinued on December 31, 2015. Statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan). The survival rate was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the survival curve was compared using the log-rank test. A p value of <0.05 was regarded as significant.

Results

Characteristics and clinical features

Thirty patients were diagnosed with pulmonary nocardiosis. Nineteen and 11 patients were men and women, respectively, and the age ranged from 25-88 years old (mean: 65.6 years old). Twenty-nine patients (96.7%) had a non-pulmonary underlying disease, such as hematologic malignancy, solid tumor (colon 2, stomach 1, lung 1, prostate 1), collagen vascular disease, Cushing's syndrome, and diabetes mellitus, or an underlying pulmonary disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and interstitial pneumonia. Thirteen patients (43.3%) were treated with immunosuppressant agents. Three patients (10.0%) were treated with sulfatomethoxazole-trimethoprim (ST) to prevent Pneumocystis pneumonia (Table 1). The condition was judged as colonization in three patients during the investigation period.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Pulmonary Nocardiosis.

| No. (%) of Cases | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 19 | (63.3) |

| Mean Age, Yr. [range] | 65.6 [25-88] | |

| Non-pulmonary underlying disease | 25 | (83.3) |

| Hematologic malignancy | 10 | (33.3) |

| Solid tumor | 5 | (16.7) |

| Connective tissue disease, vasculitis | 3 | (10.0) |

| Cushing syndrome | 2 | (6.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 | (6.7) |

| Human immunodeficiency virus infection | 2 | (6.7) |

| Auto-immune hepatitis | 1 | (3.3) |

| Pulmonary underlying disease | 9 | (30.0) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3 | (10.0) |

| Interstitial pneumonia | 2 | (6.7) |

| Bronchiectasis | 2 | (6.7) |

| Bronchial asthma | 1 | (3.3) |

| Non-tuberculous mycobacteria | 1 | (3.3) |

| No underlying disease | 1 | (3.3) |

| Immunosuppressant agents | 13 | (43.3) |

| Corticosteroids | 8 | (26.7) |

| Corticosteroids+Cyclosporin | 4 | (13.3) |

| Corticosteroids+Tacrolimus | 1 | (3.3) |

| Prophylaxis with sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim | 3 | (10.0) |

The initial symptoms were a fever (33.3%) and sputum (30.0%) in many cases, and coughing (13.3%), chest pain (10.0%), and anorexia (10.0%) were also frequently noted. Three patients (10.0%) were asymptomatic, and the detection of an abnormal shadow on chest radiography led to the diagnosis.

Radiographic findings

On chest radiography, solitary or multiple shadows of infiltration and nodules with a homogeneous density were observed in many patients. Chest CT was performed in 29 patients. Solitary infiltrative shadows were observed in 9 (31.0%) of them, making them the most frequent finding, followed by solitary mass shadows in 6 (20.7%). Multiple shadows of infiltration or mass were observed or were mixed in many patients, and a cavity was present in the infiltration or mass shadows in 8 patients (27.6%). Retention of pleural effusion was observed in 3 patients (10.0%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Chest CT Findings of Pulmonary Nocardiosis.

| No. (%) of Cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Consolidation | 9 | * | (31.0) |

| Multifocal consolidation | 1 | (3.4) | |

| Multifocal consolidation, cavitation | 1 | (3.4) | |

| Nodule | 6 | * | (20.7) |

| Nodule, cavitation | 2 | (6.9) | |

| Multiple nodules | 4 | (13.8) | |

| Multiple nodules, cavitation | 3 | * | (10.3) |

| Multifocal consolidation+multiple nodules | 1 | (3.4) | |

| Multifocal consolidation+multiple nodules, cavitation | 2 | (6.9) | |

*: Pleural Effusion (+)

Diagnosis and microbiological identification

Nocardia was isolated by culture from sputum in 24 patients (80.0%), bronchoscopic samples in 4 (13.3%), and CT-guided fine-needle aspiration samples in 2 (6.7%). It was also isolated by culture of purulent pus from the skin in 2 (6.7%) and pleural effusion and blood in 1 each (3.3%) (Table 3). The final diagnosis was pneumonia in 16 patients (53.3%) and lung abscess in 14 (46.7%), and one patient each was complicated by sepsis, brain abscess, iliopsoas abscess, and skin abscess.

Table 3.

Microbiological Characteristics of Pulmonary Nocardiosis.

| No. (%) of Cases | ||

|---|---|---|

| Source of culture | ||

| Sputum | 24 | (80.0) |

| Broncho-alveolar lavage | 4 | (13.3) |

| CT-guided needle aspiration | 2 | (6.7) |

| Purulent pus | 2 | (6.7) |

| Pleural effusion | 1 | (3.3) |

| Blood culture | 1 | (3.3) |

| Isolated organism | ||

| N. farcinica | 7 | (23.3) |

| N. nova | 6 | (20.0) |

| N. asteroides | 4 | (13.3) |

| N. cryriacigeorgica | 4 | (13.3) |

| N. brasiliensis | 3 | (10.0) |

| N. exelbida | 2 | (6.7) |

| N. abscessus | 1 | (3.3) |

| N. arthritidis | 1 | (3.3) |

| N. asiatica | 1 | (3.3) |

| N. beijingensis | 1 | (3.3) |

| N. elegans | 1 | (3.3) |

| Co-Isolated organism | ||

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 2 | (6.7) |

| Cytomegalovirus | 2 | (6.7) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 1 | (3.3) |

| Mycobacterium avium | 1 | (3.3) |

| Pneumocystis jiroveci | 1 | (3.3) |

Characteristic Gram-positive rods were confirmed by Gram and Kinyoun's stain in 28 (96.6%) of 29 patients excluding 1 patient in whom the bacterium was cultured only from blood. Thirty-one strains of Nocardia were isolated and identified. Seven strains (23.3%) of Nocardia farcinica were isolated, making this species the most frequent, followed by 6 strains (20.0%) of Nocardia nova and 4 strains (13.3%) each of Nocardia asteroids and Nocardia cryriacigeorgica (Table 3).

Twenty-six strains were subjected to drug susceptibility tests. All strains were susceptible to imipenem (or meropenem), amikacin, and minocycline, but susceptibility to other antibiotics varied. Two strains of Nocardia farcinica (7.7%) were resistant to ST.

Seven patients (23.3%) were diagnosed with mixed infection, and the causative microorganism was Aspergillus fumigatus and cytomegalovirus in 2 patients each (6.7%), and Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycobacterium avium, and Pneumocystis jiroveci in one patient each (3.3%) (Table 3).

Treatment and outcome

Treatment was initiated with single or combination antibiotics therapy, such as ST, carbapenem, and minocycline in most cases. The duration of treatment ranged from 3 days to 55 months. ST was inevitably withdrawn due to adverse reactions, such as digestive symptoms, renal insufficiency, and drug eruptions, in 47% of ST-treated patients.

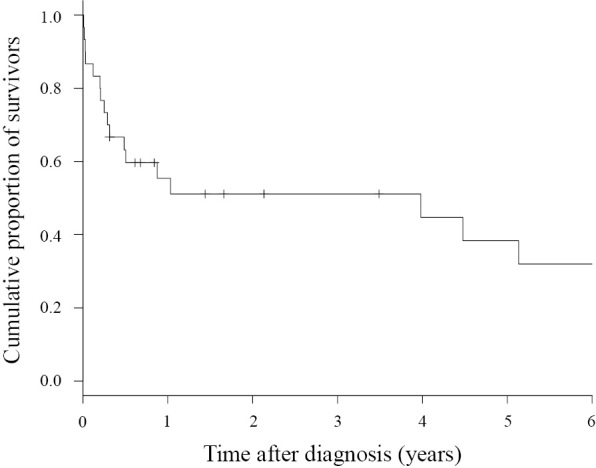

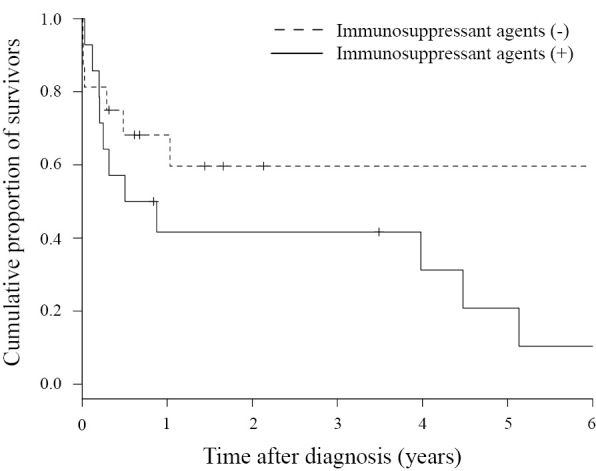

Regarding the outcome, 17 patients died, and the crude mortality rate was 56.7%. The duration of the observation period ranged from 3 days to 190 months (median: 9.2 months), and the 1-year survival rate was 55.4% (Fig. 1). When the survival period was investigated based on the presence or absence of immunosuppressant agents, the 1-year survival rates in the group with (13 patients) and without (17 patients) these treatments were 41.7% and 59.7%, respectively, showing that the prognosis tended to be poorer in the treated group (p=0.098) albeit without a significant difference (Fig. 2). The cause of death was assumed to be the underlying disease, such as malignant disease, in 10 of the 17 patients that died and Nocardia infection in the other 7 patients, but no marked differences were noted in the survival period between these 2 groups.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve of patients with pulmonary nocardiosis (n=30).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve of patients with pulmonary nocardiosis without immunosuppressant agents (n=17, the dotted line) and with immunosuppressant agents (n=13, solid line).

Discussion

Nocardiosis develops as an opportunistic infection in patients with impaired cellular immunity due to steroids and immunosuppressor treatments, malignant tumor, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome. In addition, the presence of chronic respiratory disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, is a risk factor of pulmonary nocardiosis (1-14). Underlying disease was present in 96.7% of the patients, and 13 patients (43.3%) received immunosuppressant agents, but the initial symptom and laboratory test findings were nonspecific in all cases. Shadows of multiple masses and infiltration and cavity formation, which are typical conventional findings, were observed on CT, but no characteristic findings of this disease were clarified (17-19).

An important finding of this study was the detection of the characteristic Gram-positive rods of Nocardia in 28 (96.6%) of the 29 patients examined by Gram staining, and it led to the rapid initiation of treatment. At present, Gram staining is the only method for the rapid diagnosis of Nocardia infection. Culture of this pathogen requires several days to several weeks, and continuation of culture is difficult due to overgrowth of other bacteria unless their growth is kept in check. It was reconfirmed that Gram staining is the most important method for achieving not only an early diagnosis and treatment but also improving the success rate of culture and administering optimum treatments based on drug susceptibility.

Drug susceptibility of Nocardia varies among the bacterial species, and Nocardia farcinica and Nocardia nova are resistant to various antibiotics. Resistance to ST, the first-choice agent, has recently been attracting attention, and the resistance rate was reported to be 0-58%. In our study, 2 strains (7.7%) were resistant. Drug susceptibility test results may vary markedly depending on differences in the epidemic bacterial species, regional differences in drug resistance, and susceptibility measurement methods (3,20-27), but a susceptibility surveillance of Nocardia in Japan is desired. In addition, 3 patients treated with oral ST to prevent Pneumocystis pneumonia developed pulmonary nocardiosis. ST is a first-line drug against Nocardia infection. Normally, the dose of ST administered to prevent Pneumocystis pneumonia is 1 g daily or 2 g two to three times a week, which is lower than the dose against nocardiosis. A poor pulmonary nocardiosis-preventive effect of low-dose ST has been reported (5,6,10,28,29), and our study also suggested that the preventive effect is insufficient.

The optimum antibiotics and dose and duration for the treatment of pulmonary nocardiosis are unclear because no prospective study has been performed. ST is recommended as the first choice, and the combination of imipenem and amikacin is recommended for severe cases and central nervous system infections. Regarding the duration of treatment, 6-12 months is recommended for many cases corresponding to the underlying disease and infection lesions (2-7,25). We also initiated treatment with one or several of the drugs recommended above until the results of drug susceptibility tests were obtained. Naturally, the potential presence of a resistant strain must be considered in patients who develop nocardiosis while being treated with antibiotics. Furthermore, pulmonary nocardiosis induces mixed infection at a high frequency, being a cause of aggravation to a severe state (12-14,28). Mixed infection was noted in 7 patients (23.3%), showing that the presence of a mixed infection should be considered when diagnosing this disease and selecting antibiotics.

The 1-year survival rate in all patients was 55.4% (Fig. 1). A simple comparison of the outcome is difficult because the outcome is strongly affected by factors such as the patient background and timing of the investigation, but the outcome was poor compared with previously reported survival rates (40-100%) (6,8-13,28-30). Furthermore, the 1-year survival rate in the group treated with immunosuppressant agents was 41.7%, which was poorer than that (59.7%) in the untreated group (Fig. 2).

Several limitations associated with the present study warrant mention. First, this was a long-term 20-year retrospective study. Since there are various differences in the medical care environment between 20 years ago and now, it may be problematic to investigate the overall treatment effect and outcome. The short-term prospective accumulation of cases should therefore be performed to achieve a more accurate view. Second, pulmonary nocardiosis was unlikely to be definitively diagnosed unless it was strongly suspected based on the results of Gram staining; as such, it is very possible that patient selection was biased, with our population potentially including only subjects in whom the characteristic Gram-positive rod had been detected. Pulmonary nocardiosis might be included in an opportunistic respiratory infection treated as those of unclear causative pathogens. Third, Nocardia species were identified by various methods, such as biochemical identification tests, a 16S-ribosomal RNA nucleotide sequence analysis, and mass spectrometry. Since an increasing number of Nocardia species have recently been identified, those previously identified by biochemical tests may be differently named today.

Although pulmonary nocardiosis is relatively rare, it is a major opportunistic infection. The prognosis of pulmonary nocardiosis is not favorable, and the outcome was particularly poor in patients treated with immunosuppressant agents. Pulmonary nocardiosis should be considered when a respiratory infection develops in these patients. We want to emphasize that confirmation of the characteristic Gram-positive rod by active high-quality sample collection and Gram staining is most important for the early diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

We are grateful to the staff of Medical Mycology Research Center, Chiba University, and Clinical Laboratory, Chiba University Hospital, for performing the identification tests.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1.Brown-Elliott BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, Wallance RJ Jr. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev 19: 259-282, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martínez R, Reyes S, Menéndez R. Pulmonary nocardiosis: risk factors, clinical features, diagnosis and prognosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med 14: 219-227, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson JW. Nocardiosis: Updates and clinical overview. Mayo Clin Proc 87: 403-407, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Salinas-Carmona MC. Current treatment for nocardia infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother 14: 2387-2398, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peleg AY, Husain S, Qureshi ZA, et al. . Risk factors, clinical characteristics, and outcome of Nocardial infection in organ transplant reciepients: a matched case-control study. Clin Infect Dis 44: 1307-1314, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minero MV, Marín M, Cercenado E, Rabadán M, Bouza E, Muñoz P. Nocardiosis at the turn of the century. Medicine 88: 250-261, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ambrosioni J, Lew D, Garbino J. Nocardiosis: Updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection 38: 89-97, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez TR, Menéndez VR, Reyes CS, et al. . Pulmonary nocardiosis : risk factors and outcomes. Respirology 12: 394-400, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muños J, Mirelis B, Aragón LM, et al. . Clinical and microbiological feature of nocardiosis. J Med Microbiol 56: 545-550, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walensky RP, Moore RD. A case series of 59 patients with nocardiosis. Infect Dis Clin Pract 10: 249-254, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chedid MBF, Chedid MF, Porto NS, Severo CB, Severo LC. Nocardial infections: report of 22 cases. Rev Inst Med trop S. Pauro 49: 239-246, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuo MH, Tsai YH, Tseng HK, Wang WS, Liu CP, Lee CM. Clinical experiences of pulmonary and bloodstream nocardiosis in two tertiary care hospitals in northern Taiwan, 2000-2004. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 41: 130-136, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torres HA, Reddy BT, Raad II, et al. . Nocardiosis in cancer patients. Medicine 81: 388-397, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hui CH, Au VWK, Rowland K, Slavotinek JP, Gordon DL. Pulmonary nocardiosis re-visited: experience of 35 patients at diagnosis. Respir Med 97: 709-717, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takiguchi Y, Uruma R. Pulmonary infection with Nocardia species: a report of 10 cases. J Jpn Respir Soc 42: 810-814, 2004. (in Japanese, Abstract in English). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurahara Y, Tachibana K, Tsuyuguchi K, Akira M, Suzuki K, Hayashi S. Pulmonary nocardiosis: A clinical analysis of 59 cases. Respir Invest 52: 160-166, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanne JP, Yandow DR, Mohammed TLH, Meyer CA. CT findings of pulmonary nocardiosis. Am J Rentogenol 197: W266-W272, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsujimoto N, Saraya T, Kikuchi K, et al. . High-resolution CT findings of patients with pulmonary nocardiosis. J Thorac Dis 4: 577-582, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehrian P, Esfandiari E, Karimi MA, Memari B. Computed tomography features of pulmonary nocardiosis in immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients. Pol J Radiol 80: 13-17, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mootsikapun P, Intarapoka B, Liawnoraset W. Nocardiosis in Srinagarind Hospital, Thailand: review of 70 cases from 1996-2001. Int J Infect Dis 9: 154-158, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uhde KB, Pathak S, McCullum Jr, et al. . Antimicrobial-resistant Nocardia isolates, United States,1995-2004. Clin Infect Dis 51: 1445-1448, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larruskain J, Idigoras P, Marimón JM, Pérez-Trallero E. Susceptibility of 186 Nocardia sp. isolates to 20 antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55: 2995-2998, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown-Elliott BA, Biehle J, Conville PS, et al. . Sulfonamide resistance in isolates of Nocardia spp. from U.S. multicenter survey. J Clin Microbiol 50: 670-672, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlaberg R, Fisher MA, Hanson KE. Susceptibity profiles of Nocardia isolates based on current taxonomy. Antimicrob Agent Chemother 58: 795-800, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark NM, Reid GE; ATS infectious, disease community, of practice Nocardia infections in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant 13: 83-92, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang HL, Seo YH, LaSala PR, Tarrand JJ, Han XY. Nocardiosis in 132 patients with cancer. Microbiological and clinical analyses. Am J Clin Pathol 142: 513-523, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McTaggart LR, Doucet J, Witkowska M, Richardson SE. Antimicrobial susceptibility among clinical Nocardia species identified by multilocus sequence analysis. Antimicrob Agent Chemother 59: 269-275, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts SA, Franklin JC, Mijch A, Spelman D. Nocardia infection in heart-lung transplant recipients at Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Australia, 1989-1998. Clin Infect Dis 31: 968-972, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Husain S, McCurry K, Dauber J, Singh N, Kusne S. Nocardia infection in lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant 21: 354-359, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosman Y, Grossman E, Keller N, et al. . Nocardiosis: A 15-year experience in a tertiary medical center in Israel. Eur J Intern Med 24: 552-557, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]