Abstract

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to examine the current evidence on the possible effects of breastfeeding on different malocclusion traits in primary and mixed dentition. A systematic search was made in three databases, using terms related to breastfeeding and malocclusion in primary and mixed dentition. Of the 31 articles that met the inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative analysis, nine were included in the quantitative analysis. The quality of the 31 observational studies was moderate to high on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. It was found that the odds ratio for the risk of posterior crossbite was 3.76 (95% CI 2.01–7.03) on comparing children who had not been breastfed, with those breastfed for over six months, and rose to 8.78 (95% CI 1.67–46.1) when those not breastfed were compared to those breastfed for over twelve months. The odds ratio for class II malocclusion in children breastfed for up to six months compared to those breastfed for over six months was 1.25 (95% CI 1.01–1.55). Lastly, children who were breastfed for up to six months had an odds ratio of 1.73 (95% CI 1.35–2.22) for non-spaced dentition compared to those who were breastfed for over six months.

Introduction

The WHO recommends exclusive breastfeeding for at least the first six months of life, as this reduces the risk of infectious diseases of the gastrointestinal tract and respiratory system1.

Craniofacial development involves functional stimuli such as respiration, mastication, sucking and swallowing2. In addition to the protection against infection afforded by breastfeeding, it has also been observed to promote correct craniofacial development owing to the intense muscular activity it requires, which favors proper lip closure, stimulates mandibular function and positions the tongue correctly against the palate3. The movements of lips and tongue during breastfeeding mean that the child obtains milk through a “squeeze action”, whereas bottle-fed children make a more passive movement to obtain the milk, causing less stimulation of the orofacial structures4.

Consequently, breastfeeding can promote better occlusal development and correct growth of the orofacial structures, and the better occlusal development can extend through into the mixed dentition stage. Nevertheless, the influence of breastfeeding on occlusion is a subject of debate in the scientific literature.

Some authors have studied the relationship between breastfeeding and occlusion and reached very different conclusions, from the absence of any association between breastfeeding and occlusion5–7 to a specific relationship between a shorter duration of breastfeeding and the appearance of particular types of malocclusion, such as posterior crossbite8–11, open bite12 or class II malocclusion13, 14.

Owing to this controversy, the aim of the present systematic review and meta-analysis is to examine the current evidence on the possible effects of breastfeeding on the different malocclusion traits in primary and mixed dentition.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was conducted in accordance with the MOOSE guidelines for Meta-analyses and Systematic Reviews of Observational Studies15. The review was registered with the PRISMA (PROSPERO) database under number CRD42016032862.

Review questions

A PICO question was formulated as follows: Population – children with primary or mixed dentition; Exposure – duration of breastfeeding; Comparison – absence of breastfeeding; Outcome – malocclusions. Is breastfeeding a protective factor against malocclusion in primary and mixed dentition? Does the duration of breastfeeding have an effect on occlusal development? What occlusal traits of primary and mixed dentition are influenced by breastfeeding?

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion

The inclusion criteria were: randomized controlled trials (RCTs), case-control studies and cohort studies in humans. Retrospective and prospective studies were both included. Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, clinical cases, case series, literature reviews and editorials were excluded. Studies that assessed the current evidence on the effect of breastfeeding on occlusion in primary and mixed dentition were included. Both exclusive and mixed breastfeeding were included in order to assess the effects on occlusion in relation to the number of months of breastfeeding.

Search strategy

To identify relevant studies irrespective of language, a rigorous electronic search was made in the Pubmed, Embase and Scopus databases. An electronic search for “grey literature” was also made in the New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature Report. The search was made with no time limit on January 30, 2017. The following search strategy was employed: (child* OR infant OR infant, newborn OR baby) AND (breastfeed* OR breast feeding) AND (dental occlusion OR occlus* OR malocclusion OR crossbite* OR bite, cross OR bites, cross OR overbite OR deep bite OR dental overjet OR incisor protrusion OR open bite). For this search strategy, both MeSH and non-MeSH terms were used. Attention was paid to the different combinations of these terms and the electronic search was complemented by hand searching for the bibliographical references cited in the eligible articles in order to add studies that had not been found during the primary search.

Two independent reviewers (MBC and MCP) assessed the titles and abstracts of all the articles selected. The Kappa score16 was used to assess the degree of agreement on eligibility on reading the title and abstract. In the event of disagreement, a third reviewer (CBA) was consulted. If the information provided by the abstract was insufficient to reach a conclusion, the reviewers read the full article before taking the final decision. Subsequently, the full texts of all the articles were read and the reasons for rejecting those excluded were recorded.

Data extraction and list of variables

The following data were extracted from each of the studies included: author, year of publication, type of study, type of dentition studied (primary or mixed), sample size, sample selection method, gender, mean age, dropouts, type of malocclusion studied, breastfeeding data collection method, results, breastfeeding-malocclusion odds ratio (OR) and quality of the article.

Quality assessment

The quality of the studies was evaluated on the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) for cohort and case-control studies17. The NOS contains eight items. Each study can be awarded only one star for each item, with the exception of Comparability, for which up to two stars can be given, so the maximum possible score for each study is nine stars. The quality of the studies was assessed independently by two reviewers. If they disagreed, a consensus was reached with a third reviewer.

Measurement of the variables and synthesis of the results

The odds ratios of associations between different lengths of breastfeeding (no breastfeeding, less than six months’ breastfeeding, over six months’ breastfeeding, over twelve months’ breastfeeding) and class II molar, openbite, non-spaced dentition and posterior crossbite were calculated.

Statistical analysis

The Odds Ratios were estimated using the calculadora_metaanalisis.xls calculator from CASPe (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Español). Heterogeneity was assessed with the Q test, at p < 0.1, as well as the I2 test. For the combination of studies, the DerSimonian-Laird random effects pooling method was used to calculate the weighted odds ratio. Rosenthal’s tolerance level was employed to assess publication bias.

Results

Study selection and flow diagram

The protocol registered with PROSPERO stated that the search would be limited to the year 2000 or later, but during the search it was decided not to apply a time limit in order not to exclude any article that met the other inclusion criteria. The database searches identified 178 articles (146 in Pubmed, 21 in Embase and 11 in Scopus) and hand-searching found three more. The number of duplicates removed was 27. Initial screening of the titles and abstracts of the resulting 154 articles led to excluding 116. The full texts of the remaining 38 were then read. Finally, the 31 articles that met all the eligibility criteria were included in the qualitative synthesis. The inter-examiner agreement was greater than 0.9. Nine of the studies were included in the meta-analyses (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram. From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

Characteristics of the studies included

Of the thirty-one articles included in the review, twenty were cross-sectional, three longitudinal, seven cross-sectional in a study cohort, and one was a case-control study. Four examined breastfeeding and malocclusion in mixed dentition and twenty-seven in primary dentition.

The sample sizes of the studies ranged between 80 and 2026. The mixed dentition ages ranged between 6 and 15 years and the primary dentition ages between 0 and 6 years.

As regards the types of malocclusion, twelve of the studies examined the relationship between breastfeeding and posterior crossbite: Limeira et al. in mixed dentition8, and the other eleven in primary dentition4, 9–11, 18–24. The relationship between breastfeeding and overbite/anterior openbite was examined by fourteen studies, all in primary dentition3, 6, 10, 12, 18–21, 24–29. The relationship between breastfeeding and overjet/anterior crossbite in primary dentition was examined by six studies3, 10, 18–20, 29.

Luz et al. and Thomaz et al.30, 31 examined the association between breastfeeding and dental/skeletal class II in mixed dentition and Nahas-Scocate et al., Caramez da Silva et al., Feldens et al. and Agarwal et al.13, 14, 32, 33 investigated the same association in primary dentition. The relationship between breastfeeding and the development of occlusion/malocclusion was analyzed in nine studies, all in primary dentition5–7, 10–12, 18, 34, 35.

The relationship between breastfeeding and the presence/absence of interdental spaces in primary dentition was examined by three studies9, 11, 33. Only one study36 investigated the association between breastfeeding and palate depth in primary dentition, and one other37 looked at the association between breastfeeding and facial pattern in mixed dentition.

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the data collected from all the studies in mixed and primary dentition, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of articles studying the relationship between breastfeeding and malocclusion in mixed dentition.

| Author (year) [reference] Type of study | N (dropouts) % gender (n) Mean age Sample selection Setting | Results | Odds Ratio | Quality Newcastle Ottawa Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limeira et al.8 (2014) Cross-sectional | 714 (-) 52.38% M (374) 47.62% F (340) 6–11 years Consecutive Brazil | Posterior crossbite greater in children not breastfed, p = 0.001 | Exposure: not breastfed, Event: posterior crossbite, OR 2.25 (1.52–3.33), p < 0.001 Exposure: breastfed for less than 6 months, Event: posterior crossbite, OR 1.76 (1.09–2.84) | 6 |

| Thomaz et al.31 (2012) Cross-sectional | 2026 (0) 44.1% M (892) 55.9% F (1168) 12–15 years Probabilistic stratified two-stage clusters Brazil | Breastfeeding for up to 6 months associated with Class II and Class III associated with bruxism. Short breastfeeding period associated with severely convex profile, less concave profile associated with oral breathing p < 0.05 | Exposure: Breastfeeding for up to 6 months with history of nocturnal bruxism, Event: Class II, OR 3.14 (1.28–7.66) p = 0.01 Exposure: Breastfeeding for up to 6 months with history of bruxism, Event: Class III, OR 2.78 (1.21–6.36) p = 0.01 | 5 |

| Sanchez Molins et al.37 (2010) Case-Control | 197 (-) 53% M (105) 47% F (92) 6–11 years Consecutive Spain | Bottle fed: upper incisors protruded, dolichofacial, mandible retruded, more frequent pacifier and thumb sucking (P = 0.023) Breast fed: more brachyfacial | — | 2 |

| Luz et al.30 (2006) Cross-sectional | 249 (-) -% M -% F 8.4 years Consecutive Brazil | No significant association between duration of breastfeeding and mandibular retrusion. Significant association between up to 6 months’ breastfeeding and NNSH and between NNSH and Class II malocclusion p < 0.05 | Exposure: breastfeeding for up to 6 months, Event: NNSH, OR 3.81 (2.12–6.86) p = 0.00. Exposure: NNSH, Event: Class II, OR 2.4 (1.20–4.90) p = 0.02 | 5 |

M: male, F: female, OR: Odds Ratio, NNSH: non-nutritive sucking habits, (-): no information.

Table 2.

Characteristics of articles studying the relationship between breastfeeding and malocclusion in primary dentition.

| Author (year) Type of study | N (dropouts) % gender (n) Mean age Sample selection Setting | Results | Odds Ratio | Quality Newcastle Ottawa Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agarwal et al.23 (2016) Cross-sectional | 415 (-) 54.9% M (228) 45.1% F (187) 4–6 years Consecutive India | Exclusive breastfeeding for up to 6 months has twofold increased probability of developing nonspaced dentition | Exposure: breastfeeding for up to 6 months, Event: nonspaced dentition, OR 1.92 (1.28–2.88) | 4 |

| Germa et al.24 (2016) Prospective | 422 (612) 50% M (212) 50% F (212) 3 years Consecutive France | Breastfeeding duration not associated with posterior crossbite. Anterior openbite more frequent in children breastfed for up to 6 months | — | 5 |

| Feldens et al.32 (2016) Cross-Sectional | 1026 (5.4%) 52% M (534) 48% F (492) 2–5 years Consecutive Brazil | Greater distocclusion in children with shorter duration of breastfeeding | Exposure: breastfeeding for up to 6 months, Event: malocclusion, OR 1.63 (CI 1.32–2.03) | 4 |

| Lopes-Freire et al.7 (2015) Cross-Sectional | 275 (-) 52.4% M (144) 47.6% F (131) 3–6 years Consecutive Spain | No significant association between breast or bottle feeding and malocclusion (p > 0.05). No association between duration of breast or bottle feeding and malocclusion. | Exposure: exclusive breastfeeding, Event: malocclusion, OR 1.37 (CI 0.34–5.51) p = 0.739 | 5 |

| Peres et al.10 (2015) Prospective cohort | 1123 (3108) 52.4% M (588) 47.6% F (535) 5 years Consecutive Brazil | Predominant breastfeeding (WHO) is related to less openbite, overjet and moderate-severe malocclusion (p = 0.019). Pacifier modifies associations. So does breastfeeding for overjet or posterior crossbite. Less openbite in children with 3 to 6 months’ breastfeeding (44%) | — | 6 |

| Chen et al.9 (2015) Cross-sectional | 734 (113) 54.2% M (398) 45.8% F (336) 4.48 ± 0.84 years Consecutive China | Breastfeeding for up to 6 months related to more posterior crossbite (OR: 3.13) (p = 0.031) and absence of spaces in upper arch (OR 1.63). More NNSH in children with fewer months’ breastfeeding (p = 0.038) | Exposure: No breastfeeding/breastfed for up to 6 months, Event: posterior crossbite, OR 3.13 (CI 1.11–8.82) p = 0.031. Exposure: No breastfeeding/ breastfed for up to 6 months, Event: absence of spaces in upper arch OR 1.63 (CI 1.23–2.98) p = 0.038. | 4 |

| Sum et al.29 (2015) Cross-sectional | 851 (24) 55.1% M (469) 44.4% F (378) 3.42 ± 1.10 years Cluster sampling China | Exclusive breastfeeding for over 6 months related to less Class II incisor relationship / overjet (p = 0.013) and greater intercanine and intermolar width (p = 0.006). No association with overbite or openbite. | Exposure: Exclusive breastfeeding for over 6 months, Event: Class II incisor relationship, OR 0.650 (0.438–0.966) p = 0.013. Exposure: Exclusive breastfeeding for up to 6 months, Event: Class II incisor relationship, OR 0.452 (0.277–0.739), p = 0.013. Exposure: Exclusive breastfeeding for over 6 months, Event: increased overjet, OR 0.511 (0.290–0.902) p = 0.021. | 4 |

| Agarwal et al.23 (2014) Retrospective cross-sectional | 415 (x) 54.9% M (228) 45.1% F (187) 4–6 years Randomized India | Greater maxillary intermolar and intercanine distances when breastfed for over 6 months (p = 0.006). More posterior crossbite in children with up to 6 months’ breastfeeding (p = 0.001). Also more NNSH with up to 6 months’ breastfeeding. | Exposure: breastfeeding for up to 6 months, Event: digit sucking, OR 2.093 (1–4.37) p = 0.046. Exposure: breastfeeding for up to 6 months, Event: NNSH, OR 1.852 (0.073–9.03) p = 0.024. Exposure: breastfeeding for up to 6 months, Event: posterior crossbite, OR 7.304 (2.68–19.89) p = 0.001. | 4 |

| Moimaz et al.28 (2014) Longitudinal cohort | 80 (40) -% M(-) -% F(-) 30 months Consecutive Brazil | Breastfeeding is related to overjet (p = 0.0001) and openbite (p = 0.002) | — | 6 |

| Galan-Gonzalez et al.11 (2014) Cross-sectional | 298 (-) 45.3% M (135) 54.7% F (163) 3–6 years Representation of districts Spain | Better occlusion with breastfeeding than bottle feeding, more Class I canine, more diastemas and primate space, less crowding, less posterior crossbite, but not statistically significant (p > 0.005) | — | 4 |

| Correa-Faria et al.12 (2014) Cross-sectional | 381 (-) 49.3% M (188) 50.7% F (193) 3–5 years Consecutive Brazil | With breastfeeding, more absence (69%) than presence (31%) of malocclusion. With no breastfeeding, more presence (54.8%) than absence (45.2%) of malocclusion (p = 0.007) | — | 5 |

| Bueno et al.27 (2013) Cross-Sectional | 138 (-) -% M -% F 4–5 years Consecutive Brazil | Pacifiers were the factor most associated with openbite, overjet and posterior crossbite (p < 0.0001) | Exposure: Breastfeeding for over 6 months, Event: no overbite, OR 2.78 (1.074–7.246) p = 0.0314. | 5 |

| Caramez da Silva et al.14 (2012) Cross-sectional in a cohort | 153 (80) 54.2% M (83) 45.8% F (70) 50 months ± 7.2. Consecutive Brazil | Breastfeeding (for over 12 months) protects against distocclusion (p < 0.001) | Exposure: Breastfeeding for over 12 months, Event: distocclusion, OR 0.44 (0.23–0.82) | 5 |

| Raftowicz-Wojcik et al.6 (2011) Cross-sectional | 245 (2) -% M(-) -% F(-) 3–5 years Consecutive Poland | More openbite with breastfeeding for 0–6 months and over 12 months (p < 0.000). More overbite with breastfeeding for over 12 months (p < 0.01). More mesial occlusion with bottle-feeding | — | 3 |

| Nahas-Scocate et al.13 (2011) Cross-sectional | 485 (-) 48.9% M (237) 51.1% F (248) 3–6 years Consecutive Brazil | With shorter breastfeeding duration, more likelihood of distal step (p < 0.001) | Exposure: No breastfeeding, Event: distal step, OR 3.54 p = 0.007. Exposure: breastfeeding for up to 3 months, Event: distal step, OR 4.10, p = 0.000 | 4 |

| Romero et al.26 (2011) Cross-sectional | 1377 (1323) 50.1% M (-) 49.9% F (-) 3–6 years Consecutive Brazil | Breastfed children presented less openbite (p < 0.05) | Exposure: No breastfeeding, Event: openbite OR 7.10 (p = 0.000). Exposure: Exposure: breastfed for up to 6 months, Event: openbite, OR 5.35 (p = 0.000) Exposure: breastfed for 6–12 months, Event: openbite, OR 4.30 (p = 0.000) | 4 |

| Massuia et al.18 (2011) Cross-sectional | 374 (14) -%M -%F 4.2 ± 0.8 years Consecutive Brazil | Exclusive breastfeeding for up to 6 months: malocclusion more prevalent.. Exclusive breastfeeding for over six months is a protective factor against overjet and anterior openbite | — | 4 |

| Diouf et al.36 (2010) Cross-sectional | 226 (-) 54.42% M (123) 45.58% F (103) 5–6 years Randomized Senegal | Combination of breast and bottle feeding causes longer and deeper maxilla than breastfeeding alone. It could not be checked whether bottle-feeding alone caused these effects (P < 0.05) | — | 5 |

| Kobayashi et al.22 (2010) Cross-sectional | 1377 (-) 50.1% M (690) 49.9% F (687) 3–6 years Consecutive Brazil | More posterior crossbite in children with no breastfeeding, less in those with over 12 months’ breastfeeding (p = 0.000). | Exposure: No breastfeeding, Event: posterior crossbite, OR 4.9 (compared to 6–12 months’ breastfeeding, p = 0.0000), OR 19.9 (compared to over 12 months’ breastfeeding, p = 0.0000) | 4 |

| Leite-Cavalcanti et al.35 (2007) Cross-sectional | 342 (-) 57.3% M (196) 42.7% F (146) 3–5 year Randomized Brazil | NNSH less frequent in breastfed children | Exposure: Artificial (bottle) feeding versus breastfeeding, Event: malocclusion, OR 5.34 (2.89–9.85) p < 0.001. | 4 |

| Peres et al.21 (2007a) Cross-sectional in a cohort | 359 (-) 53.8% M (190) 46.2% F (169) 6 years Consecutive Brazil | With few months’ breastfeeding, greater posterior crossbite (p = 0.03) | Exposure: breastfed for up to 9 months, Event: openbite, PR 1.2 (p = 0.8–1.7) Exposure: breastfed for less than 9 months, Event: posterior crossbite, PR 7.4 (1.4–38.3) | 6 |

| Peres et al.25 (2007b) Cross-sectional in a cohort | 359 (-) 53.8% M (190) 46.2% F (169) 6 years Consecutive Brazil | Breastfeeding for up to 9 months related to greater openbite | Exposure: breastfed for up to 9 months, Event: openbite, OR 2.8 (1.6–4.8) p = 0.001 | 5 |

| Lescano de Ferrer et al.20 (2006) Cross-sectional in a cohort | 290 (-) -% M -% F 5 years Consecutive Spain | Breastfeeding related to normal occlusion and less malocclusion. More overbite and less openbite with breastfeeding, no anterior crossbite with breastfeeding, anterior crossbite with artificial feeding. Posterior crossbite with artificial feeding, very low with breastfeeding (p = 0.06) | — | 4 |

| Lopez del Valle et al.34 (2006) Cross-sectional | 540 (-) 52% F (-) 48% M (-) 28 ± 14 months Consecutive Puerto Rico | Breastfeeding associated with normal occlusion, less bottle feeding and less NNSH (p = 0.004) | — | 5 |

| Viggiano et al.4 (2004) Retrospective in a cohort | 1130 (-) -% M -% F 3–5 years Consecutive Italy | Less posterior crossbite with breastfeeding, more frequent with bottle feeding (P = 0.0002) | — | 5 |

| Warren et al.5 (2002) Longitudinal | 372 (328) -% M -% F 4–5 years Consecutive EEUU | No association between breastfeeding and occlusion | — | 5 |

| Karjalainen et al.19 (1999) Cross-Sectional | 148 (31) 52.7% M (78) 47.3% F (70) 3 years (37.5 ± 2.2 months) Random Finland | No association between breastfeeding and openbite or overjet. Children with posterior crossbite had shorter breastfeeding period. | — | 6 |

M: male, F: female, OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval, PR: prevalence ratio, NNSH: non-nutritive sucking habits, (−): no information

Qualitative synthesis

The quality of the thirty-one observational studies was moderate to high in all cases according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Quality of the studies on the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies.

| Author (Year) | Selection (****) | Comparability (**) | Outcome (***) | Total Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5a | 5b | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| Agarwal et al.23 (2016) | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||||

| Germa et al.24 (2016) | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | ||||

| Feldens et al.32 (2016) | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||||

| Lopes-Freire et al.7 (2015) | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | ||||

| Peres et al.10 (2015) | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | |||

| Chen et al.9 (2015) | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||||

| Sum et al.29 (2015) | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||||

| Agarwal et al.23 (2014) | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||||

| Limeira et al.8 (2014) | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | |||

| Moimaz et al.28 (2014) | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | |||

| Galan-Gonzalez et al.11 (2014) | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||||

| Correa-Faria et al.12 (2014) | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | ||||

| Bueno et al.27 (2013) | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | ||||

| Caramez da Silva et al.14 (2012) | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | ||||

| Thomaz et al.31 (2012) | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | ||||

| Raftowicz-Wojcik et al.6 (2011) | * | * | * | 3 | ||||||

| Nahas-Scocate et al.13 (2011) | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||||

| Romero et al.26 (2011) | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||||

| Massuia et al.18 (2011) | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||||

| Diouf et al.36 (2010) | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | ||||

| Kobayashi et al.22 (2010) | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||||

| Leite-Cavalcanti et al.35 (2007) | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||||

| Peres et al.21 (2007a) | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | |||

| Peres et al.25 (2007b) | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | ||||

| Lescano de Ferrer et al.20 (2006) | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||||

| Luz et al.30 (2006) | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | ||||

| Lopez del Valle et al.34 (2006) | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | ||||

| Viggiano et al.4 (2004) | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | ||||

| Warren et al.5 (2002) | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | ||||

| Karjalainen et al.19 (1999) | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | |||

Criteria: (1) Representativeness of the exposed cohort. (2) Selection of the non-exposed cohort. (3) Ascertainment of exposure. (4) Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study. (5) Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis, (5a) for one factor and (5b) for additional factor. (6) Assessment of outcome. (7) Duration of follow-up period. (8) Adequacy of follow-up.

Table 4.

Quality of the studies on the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for case-control studies.

| Author (Year) | Selection (****) | Comparability (**) | Outcome (***) | Total Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5a | 5b | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| Sanchez-Molins et al.37 (2010) | * | * | 2 | |||||||

Criteria: (1) Adequate case definition. (2) Representativeness of the cases. (3) Selection of controls. (4) Definition of controls. (5) Comparability of cases and controls on the basis of the design or analysis, (5a) for one factor and (5b) for additional factor. (6) Ascertainment of exposure. (7) Same method of ascertainment for cases and controls. (8) Non-response rate.

As regards the relationship between breastfeeding and posterior crossbite in mixed dentition, Limeira et al.8 found that no breastfeeding or a short period of breastfeeding were more often associated with this malocclusion. In primary dentition, most authors observed a greater prevalence of posterior crossbite in the no breastfeeding or breastfeeding for up to 6 months groups4, 9–11, 19–24. Only one study found no association between the duration of breastfeeding and posterior crossbite in primary dentition24.

Concerning anterior openbite, relationships have been reported between few months of breastfeeding6, 21, 24, 25 or absence of breastfeeding12 and greater prevalence of this malocclusion. Peres et al.10 and Romero et al.26 observed a greater prevalence of anterior openbite in patients with few months of breastfeeding, and Massuia et al.18 found that breastfeeding was a protective factor against anterior openbite.

In relation to overbite, the results are contradictory. Lescano de Ferrer et al.20 and Moimaz et al.28 observed greater overbite in children with over twelve months’ breastfeeding but Bueno et al.27 observed the opposite. Sum et al.29 found no association between breastfeeding and openbite or overbite.

With regard to overjet, some authors reported a relationship between longer breastfeeding and less overjet10, 18, 29, but Moimaz et al.28 found greater overjet in children with more than twelve months’ breastfeeding.

Lastly, Lescano de Ferrer et al.20 observed a lower prevalence of anterior crossbite in children who had been breastfed.

Some of the authors who examined the relationship between breastfeeding and dental class II found that a longer period of breastfeeding was associated with less prevalence of this class of malocclusion in mixed dentition31 and in primary dentition13, 14, 32 However, no relationship between class II and breastfeeding was found by Luz et al.30 in mixed dentition or by Karjalainen et al. or Agarwal et al.19, 33 in primary dentition.

Of the authors who examined the association between breastfeeding and occlusion development, three studies concluded that breastfeeding favors better occlusion10, 11, 34 and two found greater malocclusion prevalence in the absence of breastfeeding12, 35 or with up to six months’ breastfeeding18. In contrast, three groups of researchers found no association between these two variables5–7.

Three studies examined the relationship between breastfeeding and the presence or absence of interdental spaces in primary dentition. Two concluded that breastfeeding for up to six months is related to an absence of maxillary spaces9, 33, while the third related the existence of breastfeeding to diastema and primate spaces11.

Lastly, Diouf et al.36 analyzed breastfeeding and palate depth in primary dentition and found that a combination of breastfeeding and bottle feeding produced a longer and deeper maxilla than breastfeeding alone. Sanchez Molins et al.37 examined the association between breastfeeding and facial pattern in mixed dentition and found a greater prevalence of brachyfacial pattern in children who had been breastfed.

Quantitative synthesis

Nine studies were included in the quantitative synthesis.

Association between no breastfeeding and posterior crossbite

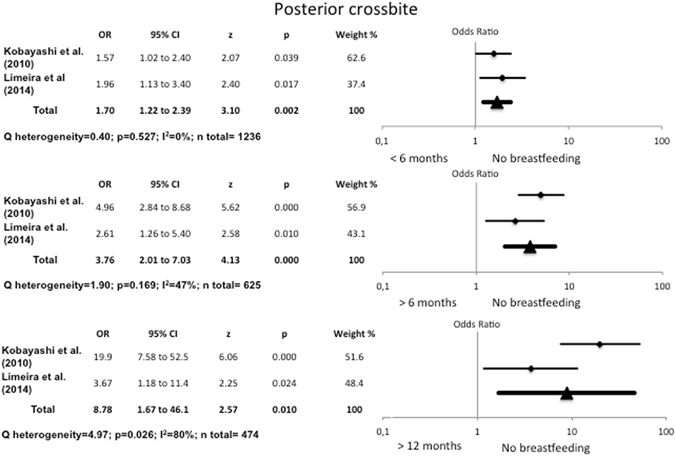

Children who were not breastfed presented 1.7 times more posterior crossbite than those who had been breastfed for between one and six months (OR = 1.70, 95% CI 1.22–2.39). Heterogeneity was very low (I2 = 0%, Q test p = 0.527). On comparing children who had not been breastfed with those who had been breastfed for over six months, the odds ratio for posterior crossbite rose to 3.76 (95% CI 2.01–7.03), with low heterogeneity (I2 = 47%, Q test p = 0.169). On comparing no breastfeeding with breastfeeding for over twelve months, the odds ratio rose to 8.78 (95% CI 1.67–46.1) (I2 = 80%, Q test, p = 0.026) (Fig. 2 ).

Figure 2.

Odds Ratio for posterior crossbite, comparing no breastfeeding with breastfeeding for <6 months, >6 months and >12 months.

Association between exclusive breastfeeding and posterior crossbite

The data for the exclusively breastfed groups proved very similar (Fig. 3). Children who were not breastfed presented 1.52 times more posterior crossbite than those exclusively breastfed for between one and six months (OR = 1.52, 95% CI 1.10–2.10). Moreover, on comparing children who had not been breastfed with those exclusively breastfed for over six months, the odds ratio for posterior crossbite rose to 3.74 (95% CI 2.13–6.58).

Figure 3.

Odds Ratio for posterior crossbite, comparing no breastfeeding with exclusive breastfeeding for <6 months and >6 months, and <6 months of exclusive breastfeeding with >6 months.

Association between duration of breastfeeding and posterior crossbite

Figure 4 shows that children who were breastfed for up to 6 months presented 2.77 times more posterior crossbite than those who had been breastfed for over 6 months (OR = 2.77, 95% CI 1.79–4.31). The heterogeneity was low (I2 = 43%, Q test p = 0.133). The data for exclusively breastfed children (Fig. 3) were very similar (OR = 2.52, 95% CI 1.52–4.14).

Figure 4.

Odds Ratio for posterior crossbite, comparing breastfeeding for <6 months with breastfeeding for >6 months and >12 months.

Additionally, the odds ratio in children breastfed for between one and six months was five times greater than for those breastfed for over twelve months (OR = 4.99, 95% CI 0.72–34.6), though the differences were not statistically significant. The heterogeneity was I2 = 87% (Q test p = 0.005) (Fig. 4).

Absence of association between breastfeeding duration and openbite

Figure 5 shows the relationship between openbite and patients who were breastfed for up to six months and for over six months. There were no significant differences between the two groups (OR = 1.76, 95% CI 0.55–5.61) and the heterogeneity was high (I2 = 75%, Q test p = 0.019).

Figure 5.

Odds Ratio for openbite, comparing breastfeeding for <6 months with breastfeeding for >6 months.

Association between breastfeeding duration and Class II molar relationship

Children who were breastfed for up to six months presented 1.25 times more Class II relationship than those who had been breastfed for over six months. There were significant differences between the two groups (OR = 1.25, 95% CI 1.01–1.55) and the heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 43%, p = 0.136) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Odds Ratio for Class II molar relationship, comparing breastfeeding for <6 months with breastfeeding for >6 months.

Association between breastfeeding duration and non-spaced dentition

Children who were breastfed for up to six months presented 1.73 times more non-spaced dentition than those who had been breastfed for over six months. There were significant differences between the two groups (OR = 1.73, 95% CI 1.35–2.22) and the heterogeneity was low (I2 = 0%, Q test p = 0.524) (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Odds Ratio for non-spaced dentition, comparing breastfeeding for <6 months with breastfeeding for >6 months.

Discussion

This systematic review examines the current evidence on the possible effects of breastfeeding on occlusal development. The consensus is clear on the greater prevalence of posterior crossbite in both mixed and permanent dentition in the absence of any form of breastfeeding, and also on the association between a longer breastfeeding period and a lower prevalence of posterior crossbite4, 8–11, 19–23, although one study found no association24. A possible explanation for this association is that breastfeeding is based on advancing the mandible and raising and lowering the tongue, which promotes balanced muscular development, whereas the main action in bottle feeding is sucking, which contracts the buccinators and favors a narrower maxilla22.

The same consensus was not found for the other malocclusions considered. For overbite, anterior openbite and overjet, the results were disparate and no homogeneous conclusion could be reached. Regarding dental and skeletal class II malocclusion, despite some discrepancies the majority of studies considered that breastfeeding is associated with less distocclusion in both primary13, 14, 32 and mixed dentition31. However, other authors19, 30, 33 found no relationship between breastfeeding and class II in mixed and primary dentition, respectively.

The present meta-analysis found that the risk of posterior crossbite falls as the duration of breastfeeding rises. It also found that the risk of posterior crossbite was 1.52 times higher in children who had not been breastfed than in those exclusively breastfed for between one and six months, and 3.74 times higher than in children exclusively breastfed for over six months.

As regards openbite/overbite, the results were contradictory. While Lescano de Ferrer et al.20 and Moimaz et al.28 observed greater overbite in children with over twelve months’ breastfeeding, Bueno et al.27 encountered the opposite, and Sum et al.29 found no association. Massuia et al.18 reported that breastfeeding was a protective factor against anterior openbite. They also found that pacifiers could have a negative effect on the duration of breastfeeding, limiting its beneficial effects on occlusion development38.

The present meta-analysis found that children who were breastfed for up to six months presented 1.25 times more risk of Class II relationship and 1.73 times more risk of non-spaced dentition than those who had been breastfed for over six months.

A very small number of studies examined the effect of breastfeeding on palate depth and facial pattern. It would be useful for future studies to include these variables.

The sample sizes were large and representative: the smallest had 80 participants28 and the largest 202631.

Almost all the studies collected the breastfeeding data through retrospective questionnaires or interviews with the parents, which could give rise to memory bias in the parents’ recollection of the number of months for which the children were breastfed. Only the 3 longitudinal studies5, 10, 28 avoided this possible bias, collecting the data prospectively.

Some limitations of the present systematic review and meta-analysis are that most of the studies did not specify whether or not breastfeeding was exclusive, or take into account possible confounders such as digit sucking or the use of a pacifier.

In an attempt to control for publication bias, the search was conducted in three databases and was complemented by a grey literature search and hand-searching.

A further limitation in this meta-analysis is a certain heterogeneity among the studies analyzed, which limited their comparability. Additionally, they were observational studies of child populations, in which it is difficult to control for confounders.

Although two systematic reviews39, 40 and three meta-analyses38, 41, 42 have been published recently, the present study provides separate assessments of the effects of breastfeeding on primary dentition and on mixed dentition, as well as a meta-analysis that examines the relations between breastfeeding and different malocclusion traits separately, including openbite, class II malocclusion and non-spaced dentition, which have not been studied in previous meta-analyses.

In conclusion, breastfeeding is a protective factor against posterior crossbite and class II malocclusion in primary and mixed dentition. The protective effect increases in line with the months of breastfeeding. There is no clear evidence for breastfeeding providing protection against other malocclusion risks such as openbite.

To avoid bias in the results would require longitudinal studies with data on the months of exclusive breastfeeding, collected prospectively through questionnaires administered to the mothers, and subsequent examination of occlusal status at the primary dentition, mixed dentition and permanent dentition stages. They should also consider confounders such as non-nutritional sucking habits and the use of baby feeding bottles.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mary-Georgina Hardinge for translating the manuscript into English.

Author Contributions

M.B.-C. and M.C.-P. participated in data collection, analysis and interpretation, and in drafting and revising the manuscript. J.M.M.-C. and C.B.-A. participated in designing and interpreting the statistical analysis and in critical revision. J.M.A.-S. participated in interpretation, drafting and revision.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). 10 Facts on Breastfeeding. WHO [Internet]. [cited September 2016] Available in: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/breastfeeding/en/ (2015).

- 2.Salone LR, Vann WF, Dee DL. Breastfeeding an overview of oral and general health benefits. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:143–51. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silveira LM, Sauer L, Maria A, Bonfanti LS, Maciel AR. Influence of breastfeeding on children’s oral skills. Rev Saúde Pública. 2013;47:37–43. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102013000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viggiano F, Fasano D, Monaco G, Strohmenger L. Breast feeding, bottle feeding and non-nutritive sucking; effects on occlusion in deciduous dentition. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:1121–3. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.029728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren JJ, Bishara SE. Duration of nutritive and nonnutritive sucking behaviours and their effects on the dental arches. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;121:347–56. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.121445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raftowicz-Wojcik K, Matthews-Brzozowska T, Kawala B, Antoszewska J. The effects of breast feeding on occlusion in primary dentition. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2011;20:371–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopes-Freire GM, et al. Exploring the association between feeding habits, non-nutritive sucking habits, and malocclusions in the deciduous dentition. Prog Orthod. 2015;16:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s40510-015-0113-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Limeira AB, Aguiar CM, Bezerra N, Cruz A. Association between breast-feeding duration and posterior crossbites. J Dent Child. 2014;81:122–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X, Ge L. Effects of breast-feeding duration, bottle-feeding duration and non-nutritive sucking habits on the occlusal characteristics of primary dentition. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12887-015-0318-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peres KG, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding and risk of dental malocclusion. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e60–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galan-Gonzalez AF, Aznar-Martín T, Cabrera-Dominguez ME, Dominguez-Reyes A. Do breastfeeding and bottle feeding influence occlusal parameters? Breastfeed Med. 2014;9:24–9. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2013.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Correa-Faria P, Ramos-Jorge ML, Martins-Junior PA, Vieira-Andrade RG, Marques LS. Malocclusion in preschool children: prevalence and determinant factors. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2014;15:89–96. doi: 10.1007/s40368-013-0069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nahas-Scocate AC, et al. Association between infant feeding duration and the terminal relationships of the primary second molars. Braz J Oral Sci. 2011;10:140–5. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242013000100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caramez da Silva F, Giugliani ER, Pires SC. Duration of breastfeeding and distoclusion in the deciduous dentition. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7:464–8. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2011.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroup DF, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wells, G., et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (2017).

- 18.Massuia JM, Carvalho WO, Matsuo T. Má oclusao, hábitos bucais e aleitamento materno: Estudo de base populacional em um município de Pequeno Porte. Pesq Bras Odontoped Clin Integr. 2011;11:451–5. doi: 10.4034/PBOCI.2011.113.22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karjalainen S, Ronning O, Lapinleimu H, Simell O. Association between early weaning, non-nutritive sucking habits and occlusal anomalies in 3-year-old finnish children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1999;9:169–173. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.1999.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lescano de Ferrer A, Varela de Villalba TB. Effect of the suction-swallowing action on orofacial development and growth. Rev Fac Cien Med Univ Nac Cordoba. 2006;63:33–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peres KG, Barros AJD, Peres MA, Victora CG. Effects of breastfeeding and sucking habits on malocclusion in a birth cohort study. Rev Saúde Pública. 2007;41:343–50. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102007000300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi HM, Scavone H, Jr, Ferreira RI, Garib DG. Relationship between breastfeeding duration and prevalence of posterior crossbite in the deciduous dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:54–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agarwal SS, et al. Association between breastfeeding duration, non-nutritive sucking habits and dental arch dimensions in deciduous dentition: a cross-sectional study. Prog Orthod. 2014;15:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s40510-014-0059-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Germa A, et al. Early risk factors for posterior crossbite and anterior open bite in the primary dentition. Angle Orthod. 2016;86:832–838. doi: 10.2319/102715-723.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peres KG, et al. Social and biological early life influences on the prevalence of open bite in Brazilian 6-year-olds. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007;17:41–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2006.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romero C, Scavone-Junior H, Garib DG, Cotrim-Ferreira FA, Ferreira RI. Breastfeeding and non-nutritive sucking patterns related to the prevalence of anterior open bite in primary dentition. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19:161–8. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572011000200013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bueno SB, Bittar TO, Vazquez FL, Meneghim MC. Association of breastfeeding, pacifier use, breathing pattern and malocclusions in preschoolers. Dental Press J Orthod. 2013;18:30e1–6. doi: 10.1590/S2176-94512013000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moimaz SA, et al. Longitudinal study of habits leading to malocclusion development in childhood. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sum FG, et al. Association of breastfeeding and three-dimensional dental arch relationships in primary dentition. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luz C, Garib D, Arouca R. Association between breastfeeding duration and mandibular retrusion: a cross-sectional study of children in the mixed dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:531–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomaz EB, Cangussu MC, Assis AM. Maternal breastfeeding, parafunctional oral habits and malocclusion in adolescents: a multivariate analysis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;76:500–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feldens CA, et al. Factors associated with the occurrence of distoclusion in the primary dentition: A hierarchical analysis. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2016;40:88–93. doi: 10.17796/1053-4628-40.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agarwal SS, et al. Validation of association between breastfeeding duration, facial profile, occlusion and spacing: a cross-sectional study. IJCPD. 2016;9:162–6. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopez del Valle LM, Singh D, Feliciano N, Machuca MC. Associations between a history of breastfeeding, malocclusion and parafunctional habits in Puerto Rican children. P R Health Sci J. 2006;25:31–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leite-Cavalcanti A, Medeiros-Bezerra PK, Moura C. Breastfeeding, bottle feeding, sucking habits and malocclusions in Brazilian pre-school children. Rev Salud Publica. 2007;9:194–204. doi: 10.1590/S0124-00642007000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diouf JS, et al. Influence of the mode of nutritive and non-nutritive sucking on the dimensions of primary dental arches. Int Orthod. 2010;8:372–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ortho.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanchez Molins M, Grau J, Lischeid C, Ustrell JM. Comparative study of the craniofacial growth depending on the type of lactation received. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2010;11:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaafar SH, Ho JJ, Jahanfar S, Angolkar M. Effect of restricted pacifier use in breastfeeding term infants for increasing duration of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;30(8):CD007202. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007202.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hermont AP, et al. Breastfeeding, bottlefeeding practices and malocclusion in the primary dentition: a systematic review of cohort studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:3133–51. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120303133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abreu LG, Paiva SM, Pordeus IA, Martins CC. Breastfeeding, bottle feeding and risk of malocclusion in mixed and permanent dentitions: a systematic review. Braz Oral Res. 2016;30:e22. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2016.vol30.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peres KG, Cascaes AM, Nascimento GG, Victora CG. Effect of breastfeeding on malocclusions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:54–61. doi: 10.1111/apa.13103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Victora CG, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;30:475–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]