Abstract

PURPOSE

Bone fracture risk assessed ancillary to positron emission tomography with computed tomography co-registration (PET/CT) could provide substantial clinical value to oncology patients with elevated fracture risk without introducing additional radiation dose. The purpose of our study was to investigate the feasibility of obtaining valid measurements of bone mineral density (BMD) and finite element analysis-derived bone strength of the hip and spine using PET/CT examinations of prostate cancer patients by comparing against values obtained using routine multidetector-row computed tomography (MDCT) scans—as validated in previous studies—as a reference standard.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Men with prostate cancer (n=82, 71.6±8.3 years) underwent Fluorine-18 NaF PET/CT and routine MDCT within three months. Femoral neck and total hip areal BMD, vertebral trabecular BMD and femur and vertebral strength based on finite element analysis were assessed in 63 paired PET/CT and MDCT examinations using phantomless calibration and Biomechanical-CT analysis. Men with osteoporosis or fragile bone strength identified at either the hip or spine (vertebral trabecular BMD ≤80mg/cm3, femoral neck or total hip T-score ≤−2.5, vertebral strength ≤6500N and femoral strength ≤3500N, respectively) were considered to be at high risk of fracture. PET/CT- versus MDCT-based BMD and strength measurements were compared using paired t-tests, linear regression and by generating Bland-Altman plots. Agreement in fracture-risk classification was assessed in a contingency table.

RESULTS

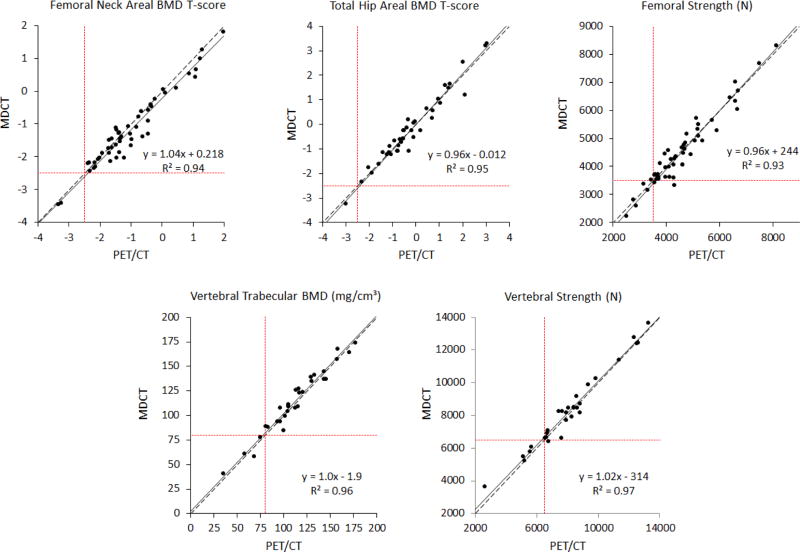

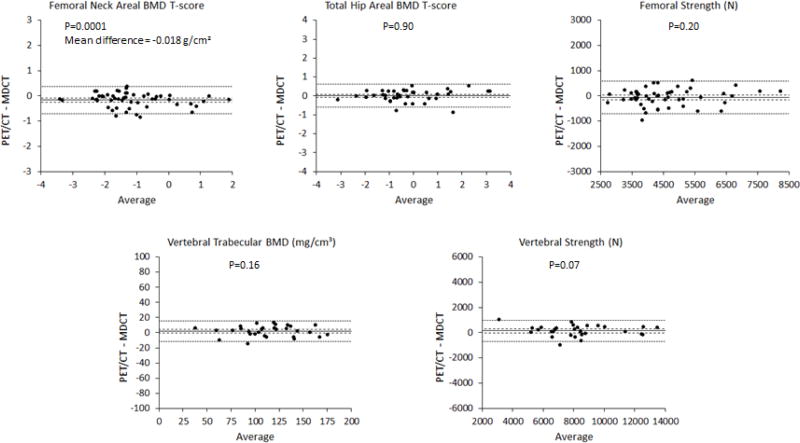

All measurements from PET/CT versus MDCT were strongly correlated (R2= 0.93–0.97; P<0.0001 for all). Mean differences for total hip areal BMD (0.001g/cm2, 1.1%), femoral strength (−60N, 1.3%), vertebral trabecular BMD (2mg/cm3, 2.6%) and vertebral strength (150N; 1.7%) measurements were not statistically significant (P>0.05 for all), whereas the mean difference in femoral neck areal BMD measurements was small but significant (−0.018 g/cm2; −2.5%; P=0.007). The agreement between PET/CT and MDCT for fracture-risk classification was 97% (0.89 kappa for repeatability).

CONCLUSION

Ancillary analyses of BMD, bone strength, and fracture risk agreed well between PET/CT and MDCT, suggesting that PET/CT can be used opportunistically to comprehensively assess bone integrity. In subjects with high fracture risk such as cancer patients this may serve as an additional clinical tool to guide therapy planning and prevention of fractures.

Keywords: 18F-NaF PET/CT, MDCT, Biomechanical-CT, finite element analysis, bone mineral density, bone strength, prostate cancer, cancer-induced bone disease

1 Introduction

Patients with prostate cancer are at a high risk of osteoporosis and fragility fractures of the spine and extremities due to associated therapies: Most regimens consist of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), in addition to radiation therapy and chemotherapy [1, 2]. ADT has been shown to negatively affect bone mineral density (BMD) [3–5] and increase the prevalence of osteoporosis to over 50% after a treatment period of 3 years [6]. Subsequently, men treated with ADT show an increase of 21–37% in fragility fractures of the spine and extremities [4]. Since prostate cancer is a chronic disease with a 5-year relative survival rate of more than 99% in the U.S. [7], the adequate diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis as a modifiable comorbidity is of high relevance. However, only a fraction of prostate cancer patients receiving ADT undergoes BMD measurements with clinically established methods such as dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), and thus remain untreated for increased bone fragility potentially resulting in significant morbidity and mortality [8, 9].

One approach to increasing screening rates is to exploit already-acquired CT scans, thus providing an ancillary but diagnostic-quality assessment of the BMD and architecture. Several approaches have been investigated for this ancillary assessment of bone parameters in already existing imaging data, such as ancillary BMD measurements derived from multidetector-row computed tomography (MDCT) [10–17], or bone strength assessment based on finite element analysis [18–20]. One comprehensive ancillary approach combines quantitative CT analysis for BMD assessment with finite element analysis for bone strength assessment, and is called Biomechanical-CT analysis [21]. In patients with inflammatory bowel disease, CT enterography-derived BMD T-score values were generated by Biomechanical-CT analysis that were highly correlated with DXA values, and patients with osteopenia and osteoporosis were correctly identified as having clinically relevant fragile bone strength [22]. Biomechanical-CT has also been validated for CT colonography in subjects undergoing colorectal cancer screening, providing BMD T-scores equivalent to DXA-derived values and bone strength values without requiring changes to the imaging protocols [23].

Imaging protocols for prostate cancer patients commonly include positron emission tomography with computed tomography co-registration (PET/CT) for staging/restaging including the assessment of bone metastasis, and treatment planning [2, 24–26]. Using these imaging data, an ancillary assessment of BMD and bone strength would be beneficial for this patient population. However, application of Biomechanical-CT to prostrate cancer patients presents some unique challenges. For example, the CT component of a PET/CT examination uses a protocol with reduced radiation doses and lower axial spatial resolution, leading to an imaging quality usually inferior to routine MDCT examinations. Also, a whole-body PET/CT protocol typically positions the patient with arms at the sides which may increase photon starvation artifacts.

The purpose of this study was therefore to evaluate the feasibility and validity of PET/CT-derived Biomechanical-CT measurements of bone strength and BMD at the hip and lumbar spine, and to validate these measurements against those derived from routine MDCT as a standard of reference.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Subjects

In our institutional database on subjects undergoing 18-F PET/CT examination according to the selection criteria from the National Oncologic PET Registry (NOPR) [27], we retrospectively searched for men who had undergone a whole-body PET/CT examination for biopsy-proven prostate adenocarcinoma and one other routine MDCT examination. We identified 82 men (mean age ± standard deviation = 71.6 ± 8.3 years) with PET/CT and routine MDCT examinations including the spine, hip, or both within a period of three months that did not receive radiation therapy between the two examinations. In these examination pairs, we assessed the feasibility of Biomechanical-CT analysis as described below.

This retrospective analysis was Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant and approved by our local institutional review board with a waiver of informed consent.

2.2 PET/CT and MDCT Imaging

For each patient, the same Biomechanical-CT analysis was performed twice: once using the CT component of the PET/CT examination (not the fused image), and once using a routine MDCT examination performed within three months of the PET/CT, either before or after. For clarity, we refer to these two imaging modalities as "PET/CT" and "MDCT," respectively.

Fluorine-18 NaF PET/CT examinations were performed on a Biograph 16 (Hi-Rez) PET/CT scanner (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany) with an integrated PET and 16-slice CT scanner. By direct venipuncture or intravenous catheter, 18F-Fluoride (185–370 MBq) was injected and approximately 60 minutes later, the CT scan was performed for attenuation correction and anatomic localization. Seventeen scans included intravenous contrast medium (150 ml Omnipaque 350, 3 ml/sec). Acquisition was performed at 120 kVp with automatic tube current modulation. Images were reconstructed with a soft tissue kernel (B19f or B40f), 50–70 cm field of view, and 4–5 mm section thickness. PET images were obtained in a three-dimensional mode at 7–10 bed positions per patient, with an acquisition time of 3–4 minutes per station, from the skull vertex through the toes.

The MDCT scans were originally acquired for abdominal and/or pelvic examinations on 12 different MDCT scanners including models from GE Healthcare (n=54), Siemens AG (n=35) and Toshiba Medical Systems (n=2). Scans were acquired at 120–140 kVp using automatic tube current modulation. Images were reconstructed at 18–50 cm field of view and 0.625–5 mm contiguous section thickness.

One radiologist with four years of experience in spine imaging (BJS) analyzed all imaging data for vertebral fractures and the presence of bone metastases in the spine and proximal femur. Single vertebral bodies with metastases or any type of fracture were not assessed with Biomechanical-CT, and subjects with metastases in all vertebral levels were excluded completely from the analysis (see 2.5). Fractures were classified as osteoporotic or potentially malignant according to established criteria [28], and deformities of fractured vertebrae were graded according to Genant et al. [29].

2.3 Biomechanical-CT Analysis

Biomechanical-CT analysis was performed by a single analyst (KJL) using the VirtuOst® software (O.N. Diagnostics, Berkeley, CA). This analysis method has been validated previously for identifying osteoporosis and assessing fracture risk based on clinical MDCT examinations [18, 21–23]. The method has been shown to be robust in both contrast-enhanced and non-contrast enhanced examinations,[18, 22, 23] and has received FDA approval for clinical use.

The primary measurements were femoral strength, DXA-equivalent measurements of areal BMD from the femoral neck and total hip regions, vertebral strength, and vertebral trabecular volumetric BMD as previously specified [18]. The same bone was analyzed for each paired PET/CT and MDCT scan. In the hip, the left proximal femur was analyzed for all except two participants due to abnormal morphology or an implant in the left femur. In the spine, L1 was selected for analysis. If L1 was not captured in both the PET/CT and MDCT scans or was diagnosed with a fracture, metastasis (see 2.2) or any other pathology such as osteoma, another vertebra from T11 to L3 that was closest to L1 and free of these findings was analyzed. As previously reported, the interoperator precision errors as a percent coefficient of variation of repeat measures were 0.57% for femoral strength, 0.45% for femoral neck areal BMD, 0.74% for vertebral strength, and 0.44% for vertebral trabecular density [30].

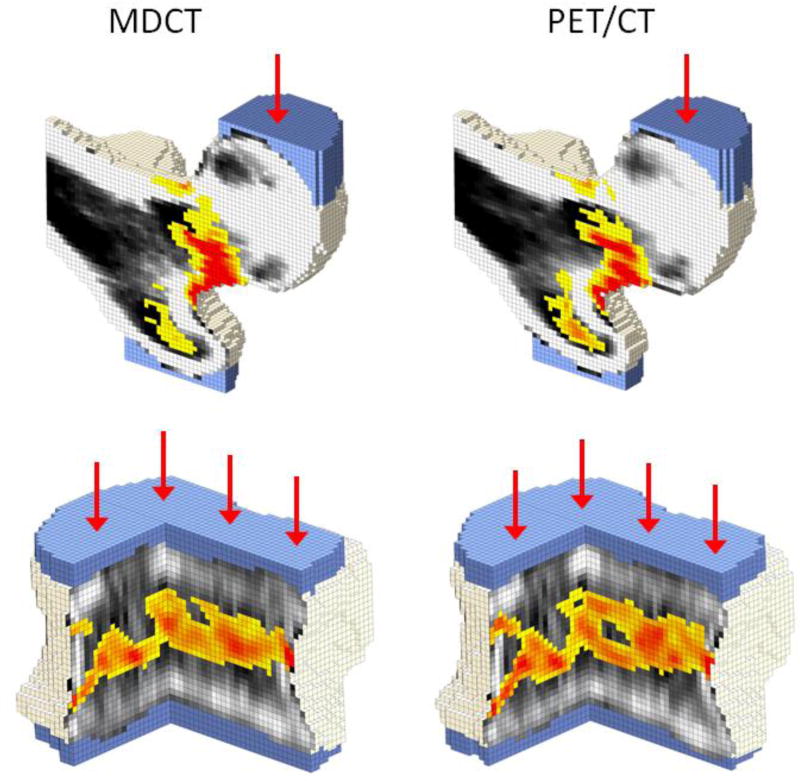

Bone strength was estimated via finite element analysis (FEA) (Figure 1) using previously described methods [20, 31]. Briefly, the CT scans were calibrated to convert CT numbers to BMD using a phantomless calibration technique based on analysis of external air and either aortic blood or visceral fat. For BCT analysis, the bone was segmented, and then routinely resampled into isotropic voxels (1.0 mm for the spine; 1.5 mm for the hip). Each voxel was then converted into an 8-noded hexahedral brick element, and assigned elastic and failure material properties based on empirical relations to BMD. With these highly reliable finite element meshes, there are no malformed elements, no stiffness artifacts due to gradients in element size, no spurious deformation modes, etc. Smaller elements are used in the vertebral body models for improved convergence of stresses near the thinner cortices and endplates. For the femur, boundary conditions were applied to simulate a sideways fall directly on the greater trochanter; for the spine, the boundary conditions represented a uniform compressive overload.

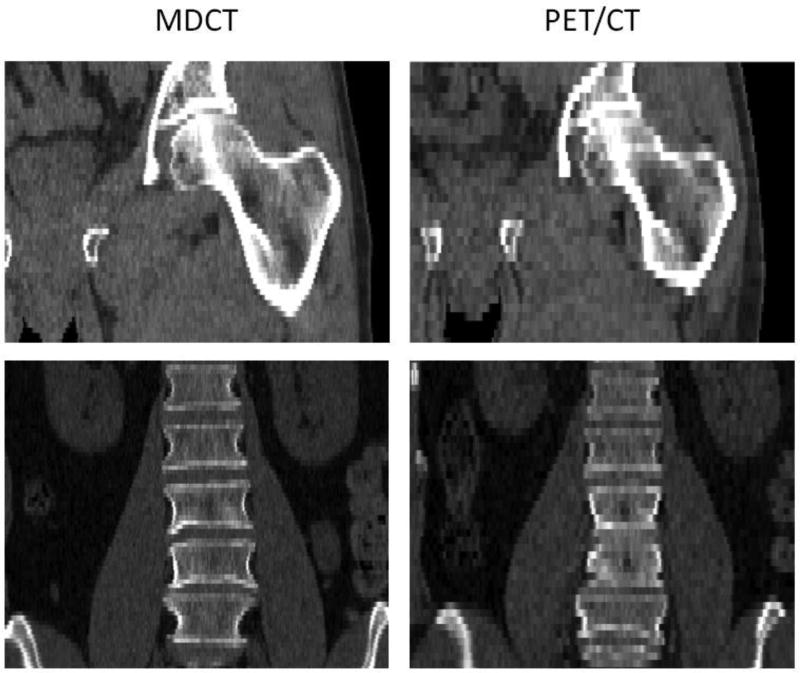

Figure 1.

MDCT (left) and PET/CT examinations (right) of a 60-year-old man. Coronal reformations showing the left proximal femur (top) and the lumbar spine (bottom). MDCT images were acquired on a Siemens Sensation Open at 120 kVp and 160–225 mAs, and reconstructed with 3 mm section thickness using a B42 kernel. The PET/CT scans were acquired on a Siemens Biograph 16 at 120 kVp and 37.5 mAs, and reconstructed with 5 mm section thickness using a B19 kernel.

The regions of interest for BMD measurements have been described previously [18]. For the hip, femoral neck and total hip areal BMD were measured from standard DXA regions on a properly oriented two-dimensional projection of the proximal femur [32]. T-scores were calculated based on a reference cohort of 409 non-hispanic white women between 20 and 29 years of age from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database [33], which can be used for the diagnosis of osteoporosis in men as previously discussed [34, 35]. For the spine, vertebral trabecular BMD was measured from an anteriorly placed elliptical region in the center of the vertebral body [18].

2.4 Fracture Risk Classification

Because a clinical decision to treat a patient typically depends on whether or not a patient is classified as being at high risk of fracture (i.e. a binary decision), we only considered two fracture-risk classifications – high risk or not high risk – in accordance with the 2015 International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD) guidelines endorsing the use of interventional thresholds [36]. A patient having either BMD-defined osteoporosis or “fragile bone strength” defined in Biomechanical-CT at either the hip or spine was considered to be at high risk of fracture [37]. According to established criteria, patients were considered to have osteoporosis when showing femoral neck or total hip T-scores ≤−2.5 based on virtual 2D images, according to guidelines [38, 39], or a vertebral trabecular BMD ≤ 80 mg/cm3 [40, 41]. For spinal measurements, the vertebral trabecular density was given instead of T-scores, since the latter have shown to be often confounded by degenerative changes, while CT-based trabecular density was more robust [18, 37, 40, 42].

Using previously established sex-specific interventional thresholds, fragile bone strength was classified on the basis of the values of a patient’s vertebral compressive strength and femoral strength with respect to the thresholds [18]. All thresholds are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameter derived from Biomechanical-CT describing osteoporosis and fragile bone strength.

| Osteoporosis [38–41] | Fragile bone strength [18] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Parameter: | Vertebral Trabecular BMD | Femoral neck or total hip T-score | Vertebral compressive strength | Femoral strength |

| High fracture risk*: | ≤ 80 mg/cm3 | ≤ −2.5 | ≤ 6500 N | ≤ 3500 N |

Patient considered at high risk of fracture if one or more of these parameters are below threshold.

2.5 Exclusions

Data for a given patient were used in the study only if Biomechanical-CT analyses could be performed at either the hip or the spine using both a PET/CT examination and a paired MDCT examination. In any of the CT examinations, the hip was not analyzed if metal artifacts from implants were present; the spine was not analyzed either if metastatic bone disease was observed in all scanned vertebral levels or if intravenous contrast medium was present. Intravenous contrast medium has been shown to substantially influence vertebral BMD measurements [43, 44] but not to appreciably influence hip measurements [22, 44].

Of the 82 subjects initially identified as eligible, 19 patients were excluded since neither their hip nor spine could be analyzed. For these patients, the hip could not be analyzed due to insufficient coverage in the MDCT image (n=6), low axial resolution of the MDCT image (n=6), excessive image artifact in the PET/CT image (n=3) or the MDCT image (n=1), or the presence of a hip implant (n=3; excluded hips overall, n=13). The spine could not be analyzed for these 13 patients due to the presence of intravenous contrast medium in either the PET/CT or MDCT image or both (n=7), metastatic bone disease in all scanned vertebral levels (n=4), low axial resolution of the MDCT image (n=3), excessive image artifact in the PET/CT image (n=1), or use of a non-standard reconstruction algorithm in the MDCT image (n=1; excluded spines overall, n=13).

2.6 Statistical Analysis

Besides descriptive statistics, mean PET/CT and MDCT derived values were compared by using paired t-tests. Correlations between PET/CT and MDCT derived values were calculated by using orthogonal linear regression models. To further illustrate agreement between the two modalities, Bland-Altman plots were produced. To assess the possible influence of scanner type and section thickness, multiple linear regression analyses were used to determine if these factors affected the comparison between PET/CT and MDCT measurements. Post hoc paired t-tests were used to assess mean differences within levels of any significant confounding variable. To assess the agreement between PET/CT and MDCT for fracture risk classification, percent agreement and Cohen's kappa [45] for repeatability were calculated and a 2×2 contingency table was constructed. Statistical analyses were performed with JMP v9.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), using a two-sided, 0.05 level of significance.

3 Results

3.1 Study Cohort

The Biomechanical-CT analyses for the 69 patients were performed using both imaging modalities at the hip only (n=35), spine only (n=12), or at both sites (n=22). Average time between the two examinations was 37±40 days, and ages of patients ranged from 56 to 86 years (mean ± standard deviation, 71.5 ± 7.6).

Overall, 19 prevalent vertebral fractures were found in 10 patients (12.2%), of which 16 fractures (84.2%) were classified as osteoporotic and 3 (15.8%) as malignant. Of these fractures, 8 (50.0%) were graded as mild, 5 (26.3%) as moderate, and 6 (31.6%) as severe. Two malignant fractures were graded as moderate, and one as severe.

3.2 Comparison of Bone Strength and BMD Measurements

Overall, the bone mineral density measurements derived from PET/CT agreed well with those from MDCT. The measurements from the two imaging modalities were strongly correlated with each other (R2=0.93–0.97; p<0.001 for all, Figure 3). On average, there were no significant difference between PET/CT and MDCT for total hip areal BMD, femoral strength, vertebral trabecular BMD, or vertebral strength (Table 2). Femoral neck areal BMD was 2.5% lower on average for PET/CT than for MDCT (p=0.0001). This difference was small compared to the variation in femoral neck areal BMD across patients (coefficient of variation = 17%; Figure 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Linear regressions (solid line) demonstrate highly significant correlations between PET/CT and MDCT measurements (p<0.001 for all plots). Total hip areal BMD, vertebral trabecular BMD and vertebral strength regression lines were not different from Y=X (dashed line) over the observed range. Femoral neck areal BMD and femoral strength show small deviations from a Y=X relationship. Values below the interventional thresholds for BMD or bone strength (dotted lines) identify patients at high risk of fracture.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of PET/CT and MDCT measurements for the proximal femur and spine.

| n | PET/CT Mean±SD (range) |

MDCT Mean±SD (range) |

PET/CT - MDCT Mean Difference [Percent], (95% CI) |

p-value from paired T-test |

95% Limits of Agreement |

R2 from linear regression1 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebral Trabecular BMD (mg/cm3) | 30 | 114 ± 33 (41–174) | 113 ± 33 (35–177) | 2 [1.6%] (−1, 4) | 0.16 | ± 14 | 0.96 |

| Vertebral Strength (N) | 30 | 8320 ± 2390 (3640–13670) | 8170 ± 2440 (2610–13280) | 150 [1.8%] (−10, 310) | 0.07 | ± 830 | 0.97 |

| Femoral Neck areal BMD (g/cm2) | 51 | 0.716 ± 0.122 (0.465–1.05) | 0.734 ± 0.127 (0.479–1.07) | −0.018 [−2.5%] (−0.027, −0.010) | 0.0001 | ± 0.061 | 0.94 |

| Total Hip areal BMD (g/cm2) | 40 | 0.921 ± 0.171 (0.548–1.34) | 0.920 ± 0.166 (0.573–1.31) | 0.001 [0.1%] (−0.011, 0.013) | 0.90 | ± 0.074 | 0.95 |

| Femoral Strength (N) | 51 | 4530 ± 1260 (2220–8320) | 4590 ± 1210 (2490–8140) | −60 [−1.3%] (−150, 30) | 0.20 | ± 650 | 0.93 |

SD = Standard Deviation; 95% CI = 95% Confidence Intervals.

All p-values from linear regressions <0.0001

Figure 4.

Bland-Altman plots with 95% confidence intervals on the mean (dashed lines) and 95% limits of agreement (dotted lines). There was a small but significant fixed bias of 140 N (3.0% of the mean) in the femoral strength measurement. For all other parameters, there was no significant difference in the means measured from PET/CT compared to MDCT examinations (p>0.05 for all).

In exploratory analyses using multiple linear regressions, MDCT scanner manufacturer and scan section thickness were investigated as potential confounders in the PET/CT versus MDCT measurement differences. These parameters had no statistically significant effect on measurement differences (p>0.05 for all) except for vertebral strength (manufacturer: p=0.003; section thickness: p=0.03). When including both confounding variables in the model, scanner manufacturer remained statistically significant (p=0.02), but section thickness did not (p=0.65). Vertebral strength measurements from PET/CT were 4.5% higher compared to the GE MDCT measurements (p=0.0002), but no significant differences were found when comparing the PET/CT strength measurements to the Siemens MDCT measurements (p=0.27).

3.3 Fracture Risk Classification

Based on PET/CT derived BMD and bone strength measurements, 11 subjects were found to be at high risk for fracture (criteria, see Table 1), 10 in common (Table 3). Sixty-one of the 63 patients were assigned the same classification using PET/CT and MDCT which represents an overall agreement of 97%. Kappa for repeatability was 0.89.

Table 3.

Contingency table for a binary fracture-risk classification using PET/CT scans and assuming the MDCT is the reference.

| MDCT (Assumed Reference) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| High Risk | Not High Risk | Total | ||||

|

|

||||||

| PET/CT | High Risk | 10 (91%) | 1 (2%) | 11 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Not High Risk | 1 (9%) | 51 (98%) | 52 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Total | 11 | 52 | 63 | |||

|

|

||||||

| Overall agreement (± SE) = 97% ± 2.2% | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Kappa (± SE) = 0.89 ± 0.08 | ||||||

|

|

||||||

SE = Standard Error

4 Discussion

In our study, MDCT and PET/CT derived measurements of hip and spine BMD and bone strength showed highly significant correlations, and classifications of high-risk of fracture showed a substantial agreement. This suggests that PET/CT can be used opportunistically to assess bone density and strength in men with prostate cancer.

Patients with prostate cancer could benefit substantially from such opportunistic measurements due to their elevated risk of osteoporosis and fracture of the spine and extremities. A majority of the patients suffer from cancer-induced bone disease, a condition that describes not only the effects on bone health caused by the primary condition, but also by therapies against the primary condition leading to bone fragility [46, 47]. Some pathways up-regulated by prostate cancer cells such as the RANK/RANKL/OPG signaling mechanism can directly induce bone destruction [48]. Even more importantly, therapeutic hypogonadism induced by androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) may cause cancer treatment-induced bone loss [49], characterized by decreasing bone mineral density (BMD) [3–5] and increasing prevalence of osteoporosis [6]. Subsequently, men treated with ADT show a total hip, femoral neck, and lumbar spine BMD loss of up to 4.6% during the first year of treatment and an increase of 21–37% in fragility fractures of the spine and extremities [4]. Several pharmaceuticals such as denosumab or bisphosphonates have been identified to reduce fragility fracture risk in patients on ADT, and thus early diagnosis of osteoporosis would be highly beneficial for these patients [50, 51]. However, only a fraction of prostate cancer patients receiving ADT undergoes BMD screening [8, 9], and thus the vast majority of eligible patients remain untreated for their reduced bone strength and increased fracture risk. In addition, DXA as the current clinical standard has been shown to have a low sensitivity for fracture risk assessment [52]. Therefore, opportunistic assessment of BMD and fracture risk in non-dedicated, already existing imaging data could potentially close this diagnostic gap by increasing identification rates of subjects at elevated risk of fractures.

Several approaches for opportunistic BMD and fracture risk assessment have been investigated recently: Multidetector-row computed tomography (MDCT) examinations have been deemed particularly useful, since they are not only commonly used in multiple clinical contexts, but they also allow for the assessment of central regions of the skeleton such as the spine and proximal femur, where assessing fracture risk and monitoring therapy effects may be most useful [53]. Measures of bone texture derived from MDCT studies have been shown to be able to differentiate subjects with and without osteoporotic spine fractures [54], to monitor teriparatide-associated microstructural changes [55], and to assess vertebral body strength based on finite element analysis [56, 57] with a higher sensitivity in fracture risk assessment compared to DXA [19]. Furthermore, BMD equivalent values derived from asynchronously calibrated MDCT examinations have been shown to highly correlate with values obtained from phantom-calibrated QCT examinations [10, 13]. However, to our best knowledge, this is the first study reporting PET/CT derived measurements of bone strength and BMD analyzed with Biomechanical-CT.

In comparison to MDCT examinations, basing Biomechanical-CT analyses on PET/CT imaging data may be more challenging. PET/CT is associated with comparatively high overall radiation doses of up to 8.9mSv, thus substantially adding to the lifetime attributable risk of cancer predominantly in already high-risk populations [58]. In order to reduce radiation dose, PET/CT protocols are designed to provide as much functional information as possible, while the CT component primarily provides topographic information, leading to an imaging quality that usually is inferior to routine MDCT examinations. For example, at our institution, the patient’s arms are positioned next to the body during the examination, which increases image noise and the likelihood of beam hardening artifacts. Furthermore, PET/CT section thickness was higher on average compared to MDCT examinations and previous Biomechanical-CT studies had used thinner sections [18, 22, 23].

This larger average section thickness for PET/CT (5 mm versus 2.5 mm) may have affected comparability of femoral neck areal BMD values. However, the observed mean difference of 0.018 g/cm2 would correspond to a difference in BMD T-score of 0.1–0.2. Thus, this difference would only have a small effect clinically, affecting only patients who are at the diagnostic threshold (T=−2.5), and only affecting the femoral BMD measurement. We hypothesize that these differences resulted from a higher volume-averaging artifact in the femoral neck caused by the larger section thickness in PET/CT. Femoral strength and total hip areal BMD, which would be less affected by such artifact, showed higher agreement between PET/CT and MDCT as did the two spine measurements when assessing all scans.

In sub-analyses for specific MDCT scanners, the type of scanner did not significantly influence the relationship between MDCT and PET/CT measurements for femoral strength, femoral neck areal BMD, total hip areal BMD, or vertebral trabecular BMD; however, vertebral strength measurements were significantly higher when measured using the PET/CT scanner compared to the GE MDCT scanner. Due to the retrospective nature of this analysis, we are unable to assess whether this was caused by scanner-specific technical parameters or by other site-specific factors including patient positioning (e.g., positioning of the arms).

We identified 17% of our subjects to be at high risk of fracture based on PET/CT data. This corresponds well with a previous study in more than 50,000 men which reported a 5-year fracture incidence of 19% in subjects undergoing ADT [59]. The possibility of identifying these subjects prior to incident fractures could be of high clinical relevance. Of note, as with other methods for fracture risk classification, caution should be exercised especially when interpreting findings of subjects with BMD and bone strength values close to the respective thresholds. However, only few subjects showed value pairs outside the 95% limits of agreement in the Bland-Altman plots, suggesting an excellent agreement for the vast majority of measurements (Figure 3).

Our study had several limitations. First, since DXA was not acquired for the patients included in this analysis, we were not able to perform a direct comparison of PET/CT-derived BMD values with DXA. As an alternative standard of reference, we therefore used bone strength and BMD values derived from routine MDCT examinations of the same patients. It has previously been reported that Biomechanical-CT analysis software generated valid and reproducible bone strength and BMD measurements based on clinical examinations without the use of a mineral calibration phantom [22, 23]. Furthermore, the DXA-equivalent approach to measuring BMD using MDCT scans has been described before [18, 60, 61].

Interventional thresholds determining fragile bone strength were adopted from a previous study based on over 2000 spine and hip examinations [18]. While these thresholds are sex-specific, it has not been assessed yet whether other demographic, constitutional and metabolic parameters such as body mass index have not only an effect on actual fracture risk, but also on the validity of the presented thresholds defining bone strength. In future prospective studies, these parameters should therefore be taken into account.

Despite the positive results for the patients that we successfully analyzed, we could not analyze all patients. Six of eighty-two (7.3%) patients were excluded as neither the spine nor the hip could be analyzed in the PET/CT scan due to imaging artifacts, hip implants, extensive metastatic disease, or IV contrast medium in the spine. This suggests that based on imaging quality and the presence of certain conditions, some subjects or examinations may be ineligible for the technique presented. Thirteen additional patients were excluded due to the lack of an MDCT scan that would allow analysis of the same bone available in the PET/CT scan. Since exclusion criteria were heterogeneous and applied to PET/CT, MDCT and patient characteristics, we can only speculate on a possible selection bias, however, since this sample reflects a clinical patient cohort, a systematic bias should be minimal.

Due to the retrospective nature of this study and modus of patient recruitment, the additional information gathered outside clinical routine during this analysis did not immediately affect patient management. However, we are aiming for including subjects in further longitudinal analyses for evaluating the potential of the presented method for therapy guidance and monitoring.

In conclusion, we assessed the feasibility of ancillary Biomechanical-CT measurements in PET/CT. We have found substantial agreement between PET/CT and MDCT derived values indicating that ancillary BMD and bone strength measurements using Biomechanical-CT analysis software are feasible in PET/CT examinations. Obtaining this additional information without introducing additional radiation dose or requiring any extra patient procedures might be highly useful for the early detection of increased risk for fragility fractures and to guide therapy decisions.

Figure 2.

Bone strength was estimated from both the MDCT (LEFT) and the PET/CT (RIGHT) examinations using finite models. Femur models in a lateral fall configuration for a 60-year-old man are shown with a coronal section through the middle of the femoral head (TOP). Models for the L1 vertebra in axial compression for a 74-year-old man are shown with a quarter section removed (BOTTOM).

Per definition, elements with a plastic strain greater than zero were considered to have failed. These failure regions are shown in yellow-to-red. Areas of zero plastic strain are not colored; instead, black-white density maps are shown to demonstrate the influence of low density regions on local failure patterns.

Displacement boundary conditions were applied through a virtual layer of bone cement (blue) in order to distribute the load over the surface of the bone. Models based on PET/CT showed similar behavior to the models based on MDCT.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Biomechanical-CT measurements for bone mineral density (BMD) and bone strength from PET/CT are strongly correlated with those from MDCT.

Fracture-risk classification from PET/CT agrees well with that from MDCT.

Ancillary analysis of routine PET/CT examinations can provide valid assessments of BMD, bone strength, and fracture-risk classification.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R44AR057616).

D.L. Kopperdahl reports grants from the National Institutes of Health (Grant Number R44AR057616), during the conduct of the study; and employment at O.N. Diagnostics. T.M. Keaveny reports personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Agnovos Healthcare, personal fees and other from O.N. Diagnostics, outside the submitted work. In addition, T.M. Keaveny has a US Patent Application 14/311,242 pending, and a US Patent Application 14/455,867 pending and Equity interest in O.N. Diagnostics, who developed the software used in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

B.J. Schwaiger, L. Nardo, L. Facchetti, A.S. Gersing, K.J. Lee and T.M. Link have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Mohler JL, Kantoff PW, Armstrong AJ, et al. Prostate cancer, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:686–718. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intentupdate 2013. Eur Urol. 2014;65:124–137. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamada Y, Takahashi S, Fujimura T, et al. The effect of combined androgen blockade on bone turnover and bone mineral density in men with prostate cancer. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:321–327. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higano CS. Androgen-deprivation-therapy-induced fractures in men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer: what do we really know? Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2008;5:24–34. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro0995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diamond T, Campbell J, Bryant C, Lynch W. The effect of combined androgen blockade on bone turnover and bone mineral densities in men treated for prostate carcinoma: longitudinal evaluation and response to intermittent cyclic etidronate therapy. Cancer. 1998;83:1561–1566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lassemillante AC, Doi SA, Hooper JD, Prins JB, Wright OR. Prevalence of osteoporosis in prostate cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2014;45:370–381. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-0083-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanvetyanon T. Physician practices of bone density testing and drug prescribing to prevent or treat osteoporosis during androgen deprivation therapy. Cancer. 2005;103:237–241. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alibhai SM, Yun L, Cheung AM, Paszat L. Screening for osteoporosis in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy. JAMA. 2012;307:255–256. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller DK, Kutscherenko A, Bartel H, Vlassenbroek A, Ourednicek P, Erckenbrecht J. Phantom-less QCT BMD system as screening tool for osteoporosis without additional radiation. Eur J Radiol. 2011;79:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pickhardt PJ, Lee LJ, del Rio AM, et al. Simultaneous screening for osteoporosis at CT colonography: bone mineral density assessment using MDCT attenuation techniques compared with the DXA reference standard. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2194–2203. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pickhardt PJ, Pooler BD, Lauder T, del Rio AM, Bruce RJ, Binkley N. Opportunistic screening for osteoporosis using abdominal computed tomography scans obtained for other indications. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:588–595. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwaiger BJ, Gersing AS, Baum T, Noel PB, Zimmer C, Bauer JS. Bone mineral density values derived from routine lumbar spine multidetector row CT predict osteoporotic vertebral fractures and screw loosening. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:1628–1633. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Summers RM, Baecher N, Yao J, et al. Feasibility of simultaneous computed tomographic colonography and fully automated bone mineral densitometry in a single examination. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2011;35:212–216. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3182032537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baum T, Grabeldinger M, Rath C, et al. Trabecular bone structure analysis of the spine using clinical MDCT: can it predict vertebral bone strength? J Bone Miner Metab. 2014;32:56–64. doi: 10.1007/s00774-013-0465-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baum T, Muller D, Dobritz M, Rummeny EJ, Link TM, Bauer JS. BMD measurements of the spine derived from sagittal reformations of contrast-enhanced MDCT without dedicated software. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:e140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baum T, Muller D, Dobritz M, et al. Converted lumbar BMD values derived from sagittal reformations of contrast-enhanced MDCT predict incidental osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Calcif Tissue Int. 2012;90:481–487. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopperdahl DL, Aspelund T, Hoffmann PF, et al. Assessment of incident spine and hip fractures in women and men using finite element analysis of CT scans. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:570–580. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Sanyal A, Cawthon PM, et al. Prediction of new clinical vertebral fractures in elderly men using finite element analysis of CT scans. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:808–816. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orwoll ES, Marshall LM, Nielson CM, et al. Finite element analysis of the proximal femur and hip fracture risk in older men. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:475–483. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.081201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keaveny TM. Biomechanical computed tomography-noninvasive bone strength analysis using clinical computed tomography scans. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1192:57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber NK, Fidler JL, Keaveny TM, et al. Validation of a CT-derived method for osteoporosis screening in IBD patients undergoing contrast-enhanced CT enterography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:401–408. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fidler JL, Murthy NS, Khosla S, et al. Comprehensive Assessment of Osteoporosis and Bone Fragility with CT Colonography. Radiology. 2016;278:172–180. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015141984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinkawa M, Eble MJ, Mottaghy FM. PET and PET/CT in radiation treatment planning for prostate cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2011;11:1033–1039. doi: 10.1586/era.11.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Picchio M, Mapelli P, Panebianco V, et al. Imaging biomarkers in prostate cancer: role of PET/CT and MRI. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:644–655. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2982-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jadvar H. Molecular imaging of prostate cancer with PET. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1685–1688. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.126094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hillner BE, Liu D, Coleman RE, et al. The National Oncologic PET Registry (NOPR): design and analysis plan. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1901–1908. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.043687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torres C, Hammond I. Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Differentiation of Osteoporotic Fractures From Neoplastic Metastatic Fractures. J Clin Densitom. 2016;19:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:1137–1148. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engelke K, Libanati C, Fuerst T, Zysset P, Genant HK. Advanced CT based in vivo methods for the assessment of bone density, structure, and strength. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2013;11:246–255. doi: 10.1007/s11914-013-0147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crawford RP, Cann CE, Keaveny TM. Finite element models predict in vitro vertebral body compressive strength better than quantitative computed tomography. Bone. 2003;33:744–750. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00210-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonnick SL. Application and Interpretation. Humana Press; 2010. Bone Densitometry in Clinical Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plan and operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–94. Series 1: programs and collection procedures. Vital Health Stat 1. 1994:1–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Melton LJ, 3rd, Khaltaev N. A reference standard for the description of osteoporosis. Bone. 2008;42:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Looker AC, Orwoll ES, Johnston CC, Jr, et al. Prevalence of low femoral bone density in older U.S. adults from NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1761–1768. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.11.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shepherd JA, Schousboe JT, Broy SB, Engelke K, Leslie WD. Executive Summary of the 2015 ISCD Position Development Conference on Advanced Measures From DXA and QCT: Fracture Prediction Beyond BMD. J Clin Densitom. 2015;18:274–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.ACR-SPR-SSR Practice Parameter for the Performance of Quantitative Computed Tomography (QCT) Bone Densitometry Res. 32 – 2013, Amended 2014 (Res. 39) ( http://www.acr.org/~/media/ACR/Documents/PGTS/guidelines/QCT.pdf)

- 38.Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Postmenopausal Osteoporosis- 2016. Endocr Pract. 2016;22:1–42. doi: 10.4158/EP161435.GL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, et al. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:23–57. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2074-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Engelke K, Adams JE, Armbrecht G, et al. Clinical use of quantitative computed tomography and peripheral quantitative computed tomography in the management of osteoporosis in adults: the 2007 ISCD Official Positions. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11:123–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reston VA. In: ACR practice guideline for the performance of quantitative computed tomography (qct) bone densitometry. Radiology ACo, editor. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tenne M, McGuigan F, Besjakov J, Gerdhem P, Akesson K. Degenerative changes at the lumbar spine--implications for bone mineral density measurement in elderly women. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:1419–1428. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pompe E, Willemink MJ, Dijkhuis GR, Verhaar HJ, Mohamed Hoesein FA, de Jong PA. Intravenous contrast injection significantly affects bone mineral density measured on CT. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:283–289. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bauer JS, Henning TD, Mueller D, Lu Y, Majumdar S, Link TM. Volumetric quantitative CT of the spine and hip derived from contrast-enhanced MDCT: conversion factors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1294–1301. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rizzoli R, Body JJ, Brandi ML, et al. Cancer-associated bone disease. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2929–2953. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2530-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roodman GD. Mechanisms of bone metastasis. Discov Med. 2004;4:144–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dushyanthen S, Cossigny DA, Quan GM. The osteoblastic and osteoclastic interactions in spinal metastases secondary to prostate cancer. Cancer Growth Metastasis. 2013;6:61–80. doi: 10.4137/CGM.S12769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saad F, Adachi JD, Brown JP, et al. Cancer treatment-induced bone loss in breast and prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5465–5476. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.4184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perez Ruixo JJ, Zheng J, Mandema JW. Similar relationship between the time course of bone mineral density improvement and vertebral fracture risk reduction with denosumab treatment in postmenopausal osteoporosis and prostate cancer patients on androgen deprivation therapy. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;54:503–512. doi: 10.1002/jcph.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michaud LB. Managing cancer treatment-induced bone loss and osteoporosis in patients with breast or prostate cancer. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67:S20–30. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100078. quiz S31-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone. 2004;34:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Link TM. Osteoporosis imaging: state of the art and advanced imaging. Radiology. 2012;263:3–17. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12110462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ito M, Ikeda K, Nishiguchi M, et al. Multi-detector row CT imaging of vertebral microstructure for evaluation of fracture risk. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1828–1836. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Diederichs G, Link TM, Kentenich M, et al. Assessment of trabecular bone structure of the calcaneus using multi-detector CT: correlation with microCT and biomechanical testing. Bone. 2009;44:976–983. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.01.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keaveny TM, Hoffmann PF, Singh M, et al. Femoral bone strength and its relation to cortical and trabecular changes after treatment with PTH, alendronate, and their combination as assessed by finite element analysis of quantitative CT scans. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1974–1982. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mawatari T, Miura H, Hamai S, et al. Vertebral strength changes in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with alendronate, as assessed by finite element analysis of clinical computed tomography scans: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3340–3349. doi: 10.1002/art.23988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Segall G, Delbeke D, Stabin MG, et al. SNM practice guideline for sodium 18F-fluoride PET/CT bone scans 1.0. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1813–1820. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.082263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shahinian VB, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Risk of fracture after androgen deprivation for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:154–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keyak JH, Sigurdsson S, Karlsdottir G, et al. Male-female differences in the association between incident hip fracture and proximal femoral strength: a finite element analysis study. Bone. 2011;48:1239–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.03.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khoo BC, Brown K, Cann C, et al. Comparison of QCT-derived and DXA-derived areal bone mineral density and T scores. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1539–1545. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0820-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]