This study provides novel and therapeutically relevant insights to retinal function following rod death but before cone death. To determine changes in retinal output, we used a large-scale multielectrode array to simultaneously record from hundreds of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). These recordings of large-scale neural activity revealed that following the death of all rods, functionally distinct RGCs remain. However, the receptive field properties and spontaneous activity of these RGCs are altered in a cell type-specific manner.

Keywords: multielectrode array, neural degeneration, receptive field, spontaneous activity, visual system

Abstract

We have determined the impact of rod death and cone reorganization on the spatiotemporal receptive fields (RFs) and spontaneous activity of distinct retinal ganglion cell (RGC) types. We compared RGC function between healthy and retinitis pigmentosa (RP) model rats (S334ter-3) at a time when nearly all rods were lost but cones remained. This allowed us to determine the impact of rod death on cone-mediated visual signaling, a relevant time point because the diagnosis of RP frequently occurs when patients are nightblind but daytime vision persists. Following rod death, functionally distinct RGC types persisted; this indicates that parallel processing of visual input remained largely intact. However, some properties of cone-mediated responses were altered ubiquitously across RGC types, such as prolonged temporal integration and reduced spatial RF area. Other properties changed in a cell type-specific manner, such as temporal RF shape (dynamics), spontaneous activity, and direction selectivity. These observations identify the extent of functional remodeling in the retina following rod death but before cone loss. They also indicate new potential challenges to restoring normal vision by replacing lost rod photoreceptors.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This study provides novel and therapeutically relevant insights to retinal function following rod death but before cone death. To determine changes in retinal output, we used a large-scale multielectrode array to simultaneously record from hundreds of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). These recordings of large-scale neural activity revealed that following the death of all rods, functionally distinct RGCs remain. However, the receptive field properties and spontaneous activity of these RGCs are altered in a cell type-specific manner.

degeneration affects neural circuits throughout the brain. In some neurodegenerative diseases, dysfunction and death in a single cell type can cause a range of secondary effects across the circuit. For example, in retinitis pigmentosa (RP), the initial dysfunction and death of rod photoreceptors causes secondary structural changes in retinal circuits before the loss of all photoreceptors (for review see Krishnamoorthy et al. 2016; Puthussery and Taylor 2010). These changes include the retraction of bipolar cell dendrites, altered glutamate receptor expression, and cell migration (Dunn 2015; Gargini et al. 2007; Ji et al. 2012; Jones et al. 2016; Puthussery et al. 2009). To understand the functional consequences of these secondary changes, their impact on the signals sent from the retina needs to be determined. This will reveal the extent to which these changes in retinal circuitry induce subtle vs. severe changes in retinal function; it will also likely guide the development of treatments for RP that restore vision more completely.

Retinal output, like that of many neural circuits, is carried by a diversity of cell types (Baden et al. 2016; Field and Chichilnisky 2007; Masland 2012; Sanes and Masland 2015). The mammalian retina consists of more than 20 (possibly ~40) types of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). Each type has distinct receptive fields (RFs), light-response properties, and spontaneous activity, which collectivity serve to signal distinct features of visual scenes to the brain. Rod loss may impact some RGC types more severely than others (Fransen et al. 2015; Margolis et al. 2008; Sekirnjak et al. 2011; Stasheff et al. 2011; Yee et al. 2014) and thus impair some aspects of visual processing more than others. Thus determining how rod death alters retinal function requires identifying and distinguishing changes in the RFs and other functional properties among different RGC types. This knowledge will provide clues to how rod death alters the function of different types of retinal interneurons (Euler and Schubert 2015; Toychiev et al. 2013; Trenholm et al. 2012; Trenholm and Awatramani 2015; Yee et al. 2012) and downstream visual areas (Chen et al. 2016; Dräger and Hubel 1978; Fransen et al. 2015).

A key time point to understand the impact of rod death on RGC function is before the loss of cones; many patients are diagnosed with RP when daytime vision persists but they are nearly nightblind (Openshaw et al. 2008). Therefore, this is likely a time point near to which therapeutic interventions would begin. Knowing the extent to which rod death changes cone-mediated RGC light responses and RFs may lead to both earlier detection of RP and more effective therapies.

To determine changes in the function of distinct RGC types when rods have died but cones remain, we used transgenic S334ter line 3 (S334ter-3) rats (Ji et al. 2012; Liu et al. 1999). This line exhibits relatively rapid rod death but slow cone death (Ji et al. 2012; Ray et al. 2010). For example, at postnatal day 60 (P60), the age we studied animals, only 0.01% of rods remain, whereas there is no significant change in the number of cones (Ji et al. 2012; Mayhew and Astle 1997; Shin et al. 2016). Rod synaptic terminals have also likely degenerated, because there is greatly reduced immunoreactivity for the presynaptic proteins synaptophysin and bassoon in the outer plexiform layer (Shin et al. 2015). Also, rod bipolar cells exhibit retracted dendrites, suggesting a loss of the glutamate release required to establish and maintain these synapses (Cao et al. 2015; Shin et al. 2015). Therefore, S334ter-3 rats provide a temporal window in which the effects of rod death on cone-mediated RGC function can be determined. Furthermore, following rod death, cones in S334ter-3 rats reorganize their locations to form rings in the outer retina; cone cell bodies accumulate along the rings and avoid the ring centers (Ji et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2013). The cones maintain at least some synaptic connections with second-order neurons (Shin et al. 2015). Thus this animal model provides an opportunity to understand how rod death and concomitant changes in the outer retina impact cone-mediated vision.

We measured light responses and RFs from RGCs of S334ter-3 at P60 and compared them with measurements from age-matched wild-type (WT) animals. RGC light responses were measured by presenting several distinct visual stimuli while recording their spiking activity with a large-scale multielectrode array (MEA; Anishchenko et al. 2010; Field et al. 2010). This allowed recording from hundreds of RGCs simultaneously. These recordings facilitated a cell type-specific analysis of the impact of rod death across many RGC types. Some changes in RGC function were common across types; other changes were cell type specific. This led to three primary conclusions. First, parallel processing in the retina remains largely intact after the death of rods and before the loss of cones. Second, the reorganization of cones disrupts the mosaic-like organization among the spatial RFs of each RGCs type. Third, rod loss does not only lead to a loss of rod-mediated signals among RGCs; it leads to altered temporal integration of cone-mediated responses, disruptions in the function of direction-selective RGCs, and differential changes in spontaneous spiking activity across RGC types. Collectively, these results point to several important changes in cone-mediated visual signaling that should be considered when testing strategies for rescuing vision in RP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

All procedures complied with and were prospectively approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the Department of Animal Resources at the University of Southern California or Duke University. Line 3 albino Sprague-Dawley rats homozygous for the truncated murine opsin gene (creation of a stop codon at serine residue 334; S334ter-line3) were obtained from Dr. Matthew LaVail (University of California, San Francisco, CA). Homozygous S334ter-line3 female rats were crossed with Long-Evans male rats (Charles River, San Diego, CA) to produce heterozygous, pigmented offspring that were used as the model of RP in this study. S334ter-3 rats were euthanized at postnatal day 60 (P60; 8 rats from 4 litters). Age-matched wild-type (WT) Long-Evans rats were used as healthy control animals (7 rats from 3 litters). All rats were housed under a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. Both sexes of control and S334ter-3 rats were used.

Immunohistochemistry.

Retinas were obtained and processed as described previously (Ji et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2011). Eyes were enucleated from deeply anesthetized (Euthasol, 40 mg/kg; Fort Worth, TX) dark-adapted rats before a second injection of Euthasol (40 mg/kg) to euthanize (overdose) the animal. The anterior segment and lens were removed, and the eyecups were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4, for 30 min to 1 h at 4°C. Following fixation, the retinas were isolated from the eyecups and transferred to 30% sucrose in PB for 24 h at 4°C. For fluorescence immunohistochemistry, 20-µm-thick cryostat sections were incubated in 10% normal goat serum for 1 h at room temperature. They were then incubated overnight with a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against the mouse middle-wavelength-sensitive opsin (M-opsin; dilution 1:1,000; kindly provided by Dr. Cheryl Craft, University of Southern California Roski Eye Institute) or a goat polyclonal antibody against short-wavelength-sensitive opsin (S-opsin; dilution 1:1,500; no. SC-14363, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The antiserum was diluted in a phosphate-buffered solution containing 0.5% Triton X-100 at 4°C. Retinas were washed in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH = 7.4) for 45 min (3 × 15 min) and afterward incubated for 2 h at room temperature in carboxymethy-lindocyanine-3 (Cy3)-conjugated affinity-purified donkey anti-rabbit IgG (dilution 1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) or Alexa 488 anti-goat IgG (dilution 1:300; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The sections were washed for 30 min with 0.1 M PB and mounted on a glass slide with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). For whole mount immunohistochemical staining, the same procedure was used. The primary antibody incubation was for 2 days, and the secondary antibody incubation was for 1 day.

Multielectrode array recordings.

Rats were dark-adapted overnight. Eyes were enucleated from deeply anesthetized (ketamine, 100 mg/kg; Ketaset; Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA; and xylazine, 20 mg/kg; X-Ject SA; Butler Animal Health Supply, Dublin, OH) dark-adapted rats following decapitation. The anterior portion of the eye, the lens, and the vitreous were removed in carbogen-bubbled Ames’ medium (Sigma) at room temperature (22–24°C). During the dissection, retinal landmarks were used to track the orientation of retina (Wei et al. 2010). A dorsal piece of retina approximately centered along the vertical meridian was dissected and isolated from the pigment epithelium and sclera. This retinal location exhibits the highest level of M-opsin expression in cones (Ortín-Martínez et al. 2010). Only pieces that were well attached to the pigment epithelium after removal of the vitreous were used. A piece of retina was placed RGC side down on a planar array of microelectrodes (Anishchenko et al. 2010; Field et al. 2010; Litke et al. 2004). The hexagonal array consisted of 519 electrodes with 30-µm spacing. Euthanization, the retinal dissection, and mounting of the retina on the MEA were all performed in a dark room with the aid of infrared converters and infrared illumination. Care was taken to eliminate any sources of visible light. During the recording, the retina was constantly perfused with Ames’ solution (35°C) bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Spikes recorded on the MEA were identified and sorted offline using custom software as described previously (Field et al. 2007; Shlens et al. 2006). Automated spike sorting was first performed and then visually inspected on each electrode. When the user identified spike clusters that were missed by the automated procedure or single clusters that were fit with more than one Gaussian, the number of clusters was adjusted and the data were refit. Sorted (clustered) spikes were confirmed to arise from an individual neuron if they exhibited a temporal refractory period of 1.5 ms and an estimated contamination of <10% (Field et al. 2007).

Visual stimuli.

Four visual stimuli were used in this study: checkerboard noise, drifting square-wave gratings, full-field light steps, and a spatially uniform and temporally static gray screen; parameters for each stimulus are detailed below. All visual stimuli were presented on an OLED display (Emagin, SVGA+ XL-OLED, Rev 3) controlled by custom software written in LISP (generously provided by Dr. E. J. Chichilnisky). The image of the display was focused on the photoreceptors through the mostly transparent MEA using an inverted microscope (Nikon; Ti-E, ×4 objective). The mean intensity of all stimuli (static gray screen, white noise, drifting gratings, and full-field light steps) was 7,300 photoisomeriations per rod per second given the calibrated power per unit area of the video display, the emission spectrum of the display, the spectral sensitivity of the rods, and a rod collecting area of 0.5 µm2 (Baylor et al. 1984; Field and Rieke 2002; note the effect of pigment self-screening was not included). The photoisomerization rate per cone was 6,200 for M cones, assuming a peak absorption at 510 nm and a collecting area of 0.37 µm2. S-opsin activation was negligible given the emission spectra of the video display. Binary checkerboard white noise stimuli that modulated the three primaries of the video display synchronously (each pixel was either “black” or “white” on any given frame) were used to estimate the spatiotemporal RFs of the recorded RGCs. Stimulus pixels (stixels) of the checkerboard were 20 × 20 μm or 60 × 60 μm along each edge and presented on a video display refreshing at 60.35 Hz. The smaller stixels were used to measure the spatial RF at high resolution. They were refreshed every four or eight display frames (15.09 or 7.54 Hz). Larger stixels were used to estimate temporal RFs and were refreshed every display frame (60.35 Hz). Square-wave gratings drifting in 8 directions with a spatial period of 512 µm and at temporal periods of 0.5 and 2 s were used to identify and classify direction-selective (DS) ganglion cells (see below Functional classification of RGCs; see Fig. 3A). Responses to these stimuli were also used to classify other retinal cell types on the basis of their temporal modulation to the drifting grating (see Fig. 3B). Full-field light steps that cycled from white to gray to black to gray (3 s at each light level, 12 s per cycle) were presented to measure the polarity and kinetics of RGC responses to high-contrast light steps.

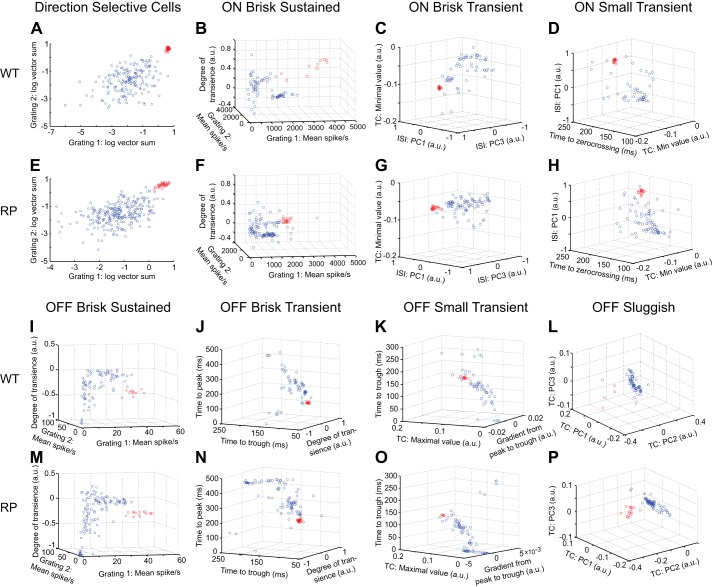

Fig. 3.

Functional classification of RGCs in WT and S334ter-3 retinas. A: identification of DS RGCs in one WT retina (WT3 in Table 1). Scatter plot shows vector sums to a high- and a low-speed drifting grating for all RGCs in one recording (gratings 1 and 2; spatial periods 512 μm, temporal periods 0.5 and 2.0 s). Data points show results of a 2-Gaussian mixture model fit. Red points are DS RGCs. B: classification of ON brisk sustained (BS) RGCs. Scatter plot shows indicated response parameters measured from all ON RGCs. Data points show results of a 2-Gaussian mixture model fit. Red points are identified ON BS RGCs. C: scatter plot showing all ON RGCs with ON BS cells removed. Data points show results of a 2-Gaussian mixture model fit to points; red points are identified ON brisk transient (BT) RGCs. D: scatter plot of remaining ON RGCs in the indicated parameter space. Data points show the results of a 2-Gaussian mixture model fit; red are identified ON small transient (ST) RGCs. E–H: same conventions as A–D but showing results of classification of each RGC type from one S334ter-3 recording (RP1 in Table 1). I–L: result of serial classification for OFF BS, BT, ST, and OFF sluggish RGCs. I shows all OFF cells, J shows all OFF cells with OFF BS cells removed, K shows all OFF cells with OFF BS and BT removed, and L shows all OFF cells with OFF BS, BT, and ST removed. Data points show the results of a 2-Gaussian mixture model fit; red points indicate the classified cells. M–P: same conventins as I–L, but for the S334ter-3 recording in E–H. a.u., Arbitrary units; TC, time course of temporal RF; PC1–PC3, principal components; ISI, interspike interval histogram.

RF measurements.

The spatial and temporal RFs of RGCs were estimated by computing the spike-triggered average (STA) to a checkerboard noise stimulus (Chichilnisky 2001; Marmarelis and Naka 1972). The temporal RF was estimated by identifying stimulus pixels with an intensity value that exceeded 4.5 robust standard deviations (SD) calculated over the intensity values of all stimulus pixels across all frames of the STA. The temporal evolution of these pixels was averaged to estimate the temporal RF. To estimate the spatial RF, the temporal RF was used as a template, and the dot product between this template and each pixel of the STA across time was computed (Chichilnisky and Kalmar 2002; Field et al. 2010). This identified the spatial profile in the STA that evolved with the temporal RF. This procedure assumes the spatiotemporal RF is the product of independent spatial and temporal RFs (i.e., the RF is space-time separable). Singular value decomposition was also used to estimate (and separate) the rank 1 spatial and temporal RFs from the STA (Gauthier et al. 2009). Use of this alternative procedure did not change any conclusions in this article. For a quantitative comparison, the time courses were fit with a difference of low-pass filters, and three features were extracted from these fits: time to peak, time to zero-crossing, and degree of transience (DoT; see Fig. 8A, top right) (Chichilnisky and Kalmar 2002; Field et al. 2007).

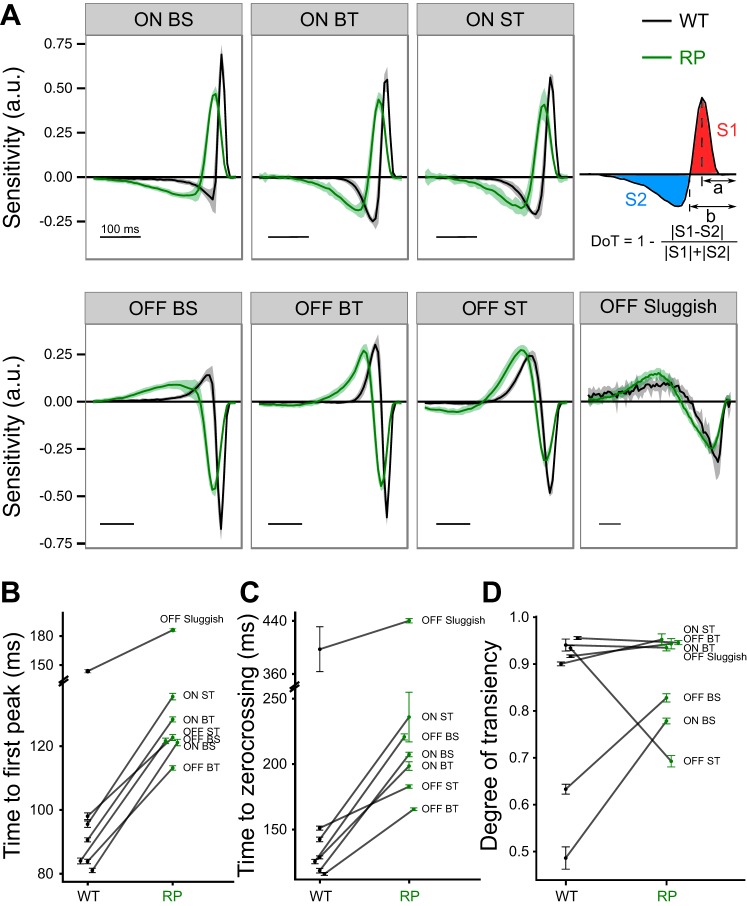

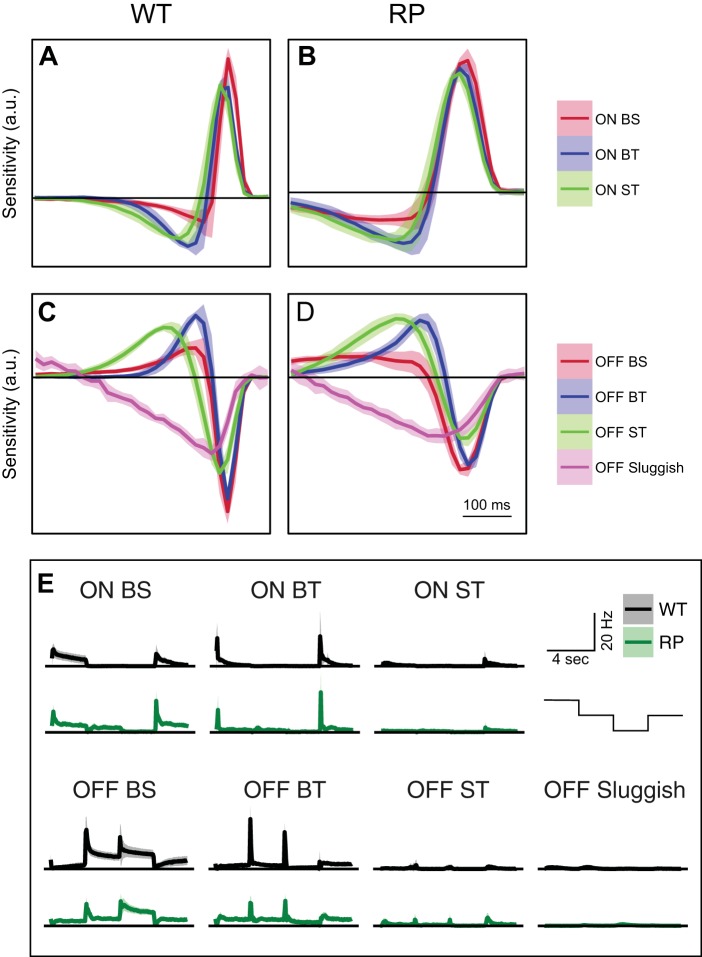

Fig. 8.

Changes in RGC temporal integration in S334ter-3 retinas. A: comparison of temporal RFs for 3 ON and 4 OFF RGC types in WT (black) and S334ter-3 retinas (green). Lines indicate mean values, and shaded areas show SE. Scale bar, 100 ms. Top right, illustration of extracted quantities from temporal RFs: time to first peak preceding spike (a), time to zero-crossing (b), and degree of transiency (DoT); S1 and S2 are areas under the curve. B–D: comparison of time to first peak (P < 0.0001 for all types; B), time to zero-crossing (C), and DoT (D) between WT and S334ter-3 retinas for 7 RGC types. Data points show mean and SE.

Binary response map.

A binary response map was generated across RGC RFs to analyze the uniformity of visual sensitivity across space (see Fig. 2). This map was calculated by overlaying individual binarized STAs. STAs were binarized by a threshold set to 4.5 SD of the distribution of STA intensity values. For pixel values larger than 4.5 SD from the mean, the pixel location was labeled 1, otherwise 0.

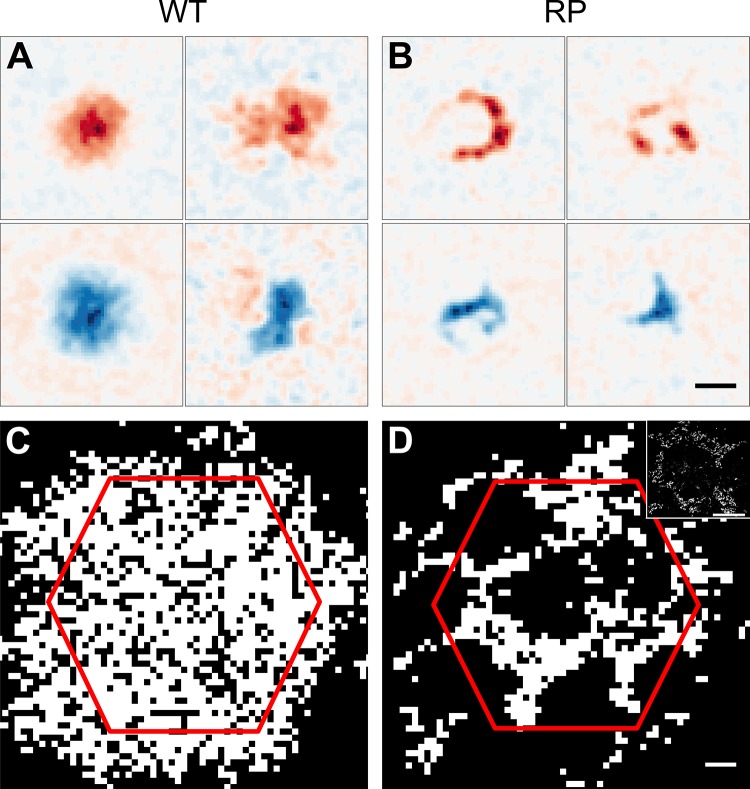

Fig. 2.

Functional changes in spatial sensitivity in S334ter-3 retina. A: spatial RFs of two ON and two OFF RGCs from WT retina. Red (blue) indicates sensitivity to increments (decrements) of light. B: spatial RFs from S334ter-3 (RP) retina. RFs exhibit holes and arc-like shapes. Scale bar, 150 μm. C: binary map indicating locations of high (white) vs. low (black) sensitivity to light cumulated across all recorded RGCs from a WT retina. D: same as C for S334ter-3 retina. Scale bar, 50 μm. Inset: micrograph shows the outer segments of cones from S334ter-3 retina at the same scale as the sensitivity map. Red hexagon in C and D is the MEA border. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Analyzing spatial RF shapes and sizes.

RF shapes were analyzed by calculating a convexity index (see Fig. 7B). This index was the ratio of the spatial RF area to the area of the convex hull of the spatial RF. For a perfectly Gaussian RF, this index will be approximately equal to 1, but it will be substantially smaller than 1 for an RF that is has a ring-like or arc-like shape. The spatial RF was estimated from the spatial component of the STA as described above. A region of interest (ROI) was defined around the spatial RF to exclude noisy stimulus pixels that could cross threshold far from the RF. This ROI was generated by downsampling the original high-resolution (20 × 20 µm) STA by fourfold (every 4 stixels in the STA were averaged to form 1 stixel) and blurred with a two-dimensional Gaussian function (SD = 8 stixels). Once the ROI was selected, significant stixels were extracted from the downsampled (but not blurred) STA by a threshold set to 4.5 SD above or below the mean stixel intensity. A convex hull was then generated from these significant stixels. RF sizes (see Fig. 7, E and F) were also calculated from the downsampled STA (without blurring) as the total area of all stixels that exceeded 4.5 SD above or below the mean. Note that DS RGCs and ON brisk sustained RGCs were excluded from this analysis because the spatial RFs did not consistently exhibit a signal-to-noise ratio sufficient to reliably estimate the shape.

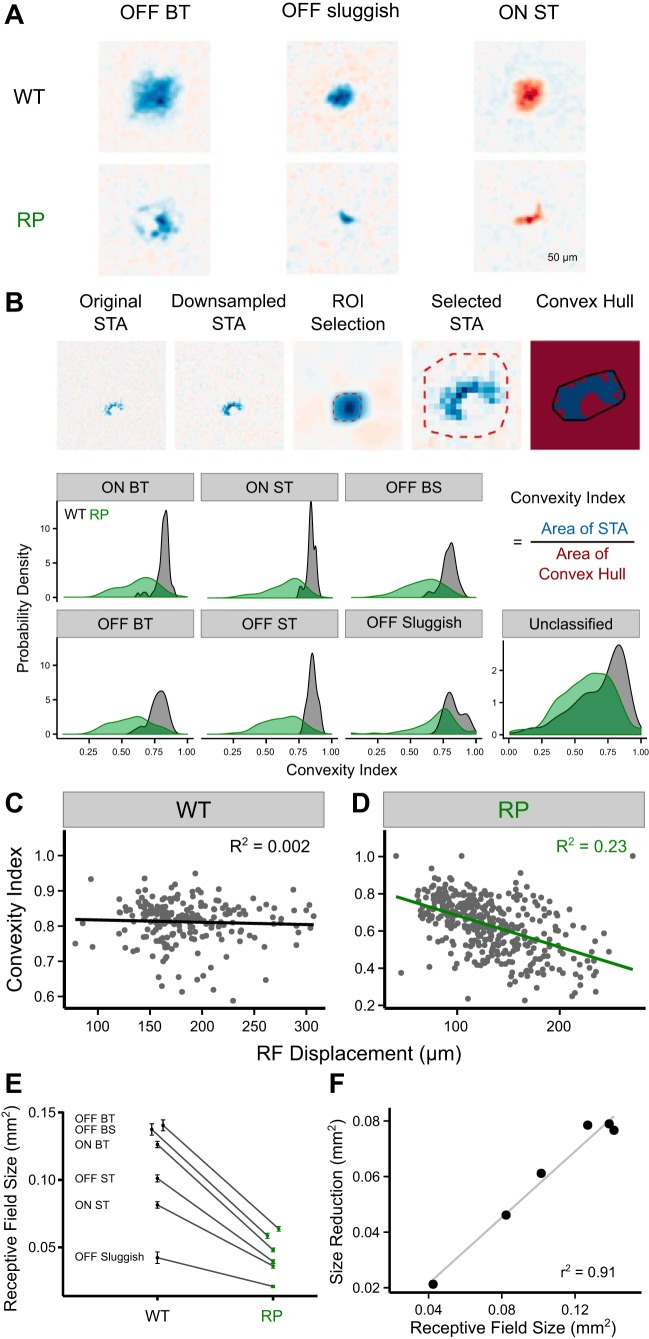

Fig. 7.

Impact of RP on the spatial RFs of distinct RGC types. A: representative spatial RFs for OFF BT, OFF sluggish, and ON ST RGCs in WT (top) and S334ter-3 retinas (RP; bottom). B: illustration of data processing for computation of the convexity index (CI; top). Bottom, probability density of CI for 3 ON, 3 OFF, and unclassified RGCs types from WT (black) and S334ter-3 retinas (green; RP). C and D: correlation between CI and RF displacement in WT (R2 = 0.002, β = −33.6, P = 0.4947) and S334ter-3 retinas (R2 = 0.23, β = −141.4, P < 0.00001). E: reduction of RF sizes in S334ter-3 retinas (P < 0.0002 for all types). Error bars are SE. F: linear relationship between spatial RF sizes estimated in WT retinas and observed size reduction in S334ter-3 retinas. Each point shows a different RGC type from E.

Functional classification of RGCs.

RGCs were classified on the basis of their light responses and intrinsic spiking dynamics. The classification was serial: in each parameter space, one type of RGC was identified; these cells were then removed from the data, and another type was identified among the remaining RGCs in a new parameter space (see Fig. 3). RGCs of a given type were first selected “by hand” by drawing a boundary in a two- or three-dimensional parameter space. To objectively define the boundary separating an RGC type from all other cells, a two-Gaussian mixture model (in 2 or 3 dimensions) was fit to capture the distribution of points in the parameter space (see Fig. 3). The initial conditions of this fit were provided by the by-hand classification.

The same parameter spaces were used at each step in the classification procedure for both WT and S334ter-3 retinas. The first step isolated DS RGCs from all other recorded cells (see Fig. 3, A and E). DS RGCs were distinguished on basis of the strength of their direction-selective index (DSI) computed from rapidly and slowly drifting square-wave gratings (temporal periods = 0.5 and 2 s, respectively). The next step separated ON from OFF RGCs by the sign of largest magnitude peak in their temporal RFs, estimated from checkerboard noise (not shown). Among ON RGCs, ON brisk sustained RGCs were isolated first by comparing their responses to rapidly and slowly drifting gratings and to the DoT of their temporal RF (see Fig. 3, B and F). ON brisk sustained RGCs formed a clear cluster in this parameter space in S334ter-3 and WT retinas (Fig. 3, B and F, red circles). Subsequently, ON brisk transient (Fig. 3, C and G) and ON small transient (Fig. 3D and H) were identified using the parameter spaces shown in Fig. 3. After these ON RGC types were classified, OFF RGCs were classified. The order and parameter spaces are illustrated in Fig. 3, with OFF brisk sustained (Fig. 3, I and M), OFF brisk transient (Fig. 3, J and N), OFF small transient (Fig. 3, K and O), and OFF sluggish cells (Fig. 3, L and P) classified in that order. This naming convention for functionally distinct RGC types is largely taken from previous work in the rabbit and cat retinas (Amthor et al. 1989a, 1989b; Caldwell and Daw 1978; Cleland et al. 1973; Cleland and Levick 1974). Different naming conventions have been used previously in the rat (Heine and Passaglia 2011), but we viewed the convention used in the rabbit as better describing the functional distinctions between RGC types measured in this study.

This classification order was used because it provided a large separation between clusters defining each cell type at each classification step. Because we did not exhaustively search all possible parameter spaces and classification orders, we cannot claim the parameter spaces or classification order used are optimal. However, this classification procedure did yield robust results across experiments in both WT and S334ter-3 retinas (see Fig. 3). Changing the classification order or using alternative parameter spaces revealed the same basic RGC types but with a higher misclassification rate as judged by RGCs with clearly distinct response properties and irregular cell spacing or mosaic violations among the spatial RFs. Use of these alternative classifications did not qualitatively change any of the results reported in this article.

Matching RGC types between WT and S334ter-3 retinas.

A minimal mapping algorithm (Ullman 1979) was used to match RGC types one-to-one between WT and S334ter-3 retinas (see Fig. 5). The most plausible matching was determined by minimizing the sum of the distances between selected properties of matched pairs. Two functional properties of RGCs were analyzed: temporal RFs and responses to full-field light steps. To match temporal RFs (Fig. 5, A–D), they were first normalized to unit magnitude and then averaged across all RGCs of a type. The sum of dot products was calculated for each possible pairing of mean temporal RFs from WT and S334ter-3 RGC types. With seven RGC types to pair (DS RGCs were excluded from this analysis), there were 5,040 summed dot products calculated. The maximum of these summed dot products was chosen as the best match. This corresponds to minimizing the angular distances between pairs. The z score for this match was 3.02, relative to the distribution of all 5,040 summed dot products.

Fig. 5.

Temporal RFs and full-field light steps match RGC types between WT and S334ter-3 retinas. A and B: mean temporal RFs of 3 ON RGC types from all WT and S334ter-3 retinas, respectively. C and D: mean temporal RFs of 4 OFF RGC types from all WT and S334ter-3 retina, respectively. Lines are average time courses. Shaded regions show the SD. RGC types were matched between WT and S334ter-3 recordings by applying a minimum matching algorithm to the RFs (see materials and methods). E: comparison of PSTHs from 3 ON and 4 OFF RGC types identified from WT and S334ter-3 retinas. RGC types were matched by applying a minimum matching algorithm to the PSTHs. Staircase at far right indicates the time course of the stimulus, which started at “white” and then transitioned through “gray,” “black,” and back to “gray,” switching intensity every 3 s. RP indicates data from S334ter-3 retinas.

Responses to full-field light steps were analyzed similarly to the temporal RFs (Fig. 5E). The peristimulus time histogram (PSTH) for each RGC in response to this stimulus was normalized to unit magnitude and then averaged over RGCs of a type separately for WT and S334ter-3 retinas. The sum of dot products between mean PSTHs for all possible pairings was calculated, and the maximum was selected as the best match. The largest sum of these dot products had a z score of 3.23 relative to the distribution of 5,040 summed dot products.

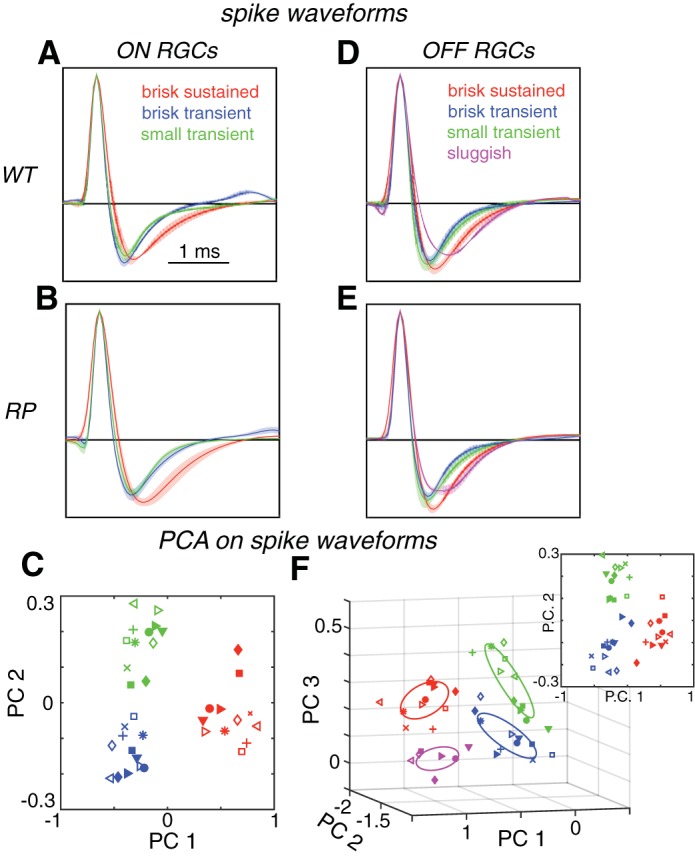

Analysis of spike shapes.

One line of evidence that RGC types were reliably matched between S334ter-3 and WT retinas was based on spike shape (see Fig. 6). In particular, RGC types with similar light-response properties between WT and S334ter-3 retinas also exhibited the greatest similarities in the shape of their average spike waveform. To estimate the spike waveform shape of each individual RGC, spikes detected on the MEA were sampled at 20 kHz. For a given RGC, spike waveforms were averaged across the two electrodes with the highest spike amplitude for that cell. Cells with their largest amplitude spike waveforms recorded on electrodes at the edge of the MEA were excluded from the analysis. These cells frequently had small signals on those electrodes, presumably because the cell body was some distance from the MEA edge. For RGCs of a given type, the spike waveforms were averaged across cells to generate the average spike waveform for that type. These waveforms were accumulated over each RGC type in seven WT and five S334ter-3 retinas. Three WT retinas were used in this analysis that were not used elsewhere because they were recorded at ages other than P60; their RGCs were classified as described above. The average spike spaces for each RGC type were then compared using principal components analysis (PCA); average spike waveforms were analyzed separately for ON and OFF RGCs (see Fig. 6). Specifically, PCA provided a low-dimensional space in which to represent the average spike waveforms for each RGC type from each recording (Fig. 6, C and F), which facilitated comparing their shapes. Spike waveforms that were similar in shape clustered together in the low-dimensional space identified by PCA, indicating spike waveforms across recordings were similar within an RGC type (for both WT and S334ter-3 animals) and distinct across RGC types.

Fig. 6.

Spike waveforms match RGC types between WT and S334ter-3 retinas. A and B: mean spike waveforms from 3 ON RGC types in WT (A) and S334ter-3 retinas (B). Solid lines are mean, and shaded areas are the SD. Spike waveforms exhibit type-dependent differences in dynamics. C: mean spike waveforms for ON BS (red), BT (blue), and ST (green) RGCs are plotted in a 2-dimensional subspace defined by PCA applied to the spike waveforms across retinas. Each symbol is the mean spike waveform for a cell type from a different recording; filled symbols are from S344ter-3 retinas. D and E: mean and SD of spike waveforms for 4 OFF RGC types from WT (D) and S334ter-3 (E). F: OFF BS (red), BT (blue), ST (green), and sluggish (magenta) RGC types are plotted in a 3-dimensional subspace defined by PCA. Ellipses show 1.3-sigma contours of 3-dimensional Gaussian fits to each group of points. Inset: 3-dimensional subspace defined by PCA applied to spike shapes for just 3 OFF RGC types yields clustering similar to that observed for the 3 ON RGC types (C).

RGC locations from electrophysiological images.

The electrophysiological image (EI) is the average electrical activity of a neuron produced across the electrode array (Field et al. 2009; Litke et al. 2004; Petrusca et al. 2007). After the spikes from a given neuron were isolated on a source electrode, the electrical activity in a time window 0.5 ms before to 3 ms after the spike was averaged over all spikes. Because the spiking activity of any given cell is largely independent from all other cells, the average electrical activity across the array reveals a unique spatiotemporal electrical “footprint” for every cell, reflecting its position, width of dendritic arbor, and axon trajectory registered to the electrode array. The EI, excluding the axon, was used to estimate the soma location of RGCs over the array by fitting a two-dimensional Gaussian. Electrodes dominated by axonal signals were excluded by identifying manually those electrodes with triphasic voltage waveforms in the EI (Litke et al. 2004). The center of the Gaussian was taken as a representation of RGC position (Li et al. 2015). Note this position need not be registered with an electrode, so the regular spacing between electrodes does not enforce regularity on the estimated RGC locations.

Quantifying the tuning of DS RGCs.

To quantify the directional tuning of DS RGCs (see Fig. 9), the average firing rates for gratings drifting in eight directions (temporal period = 0.5 s, spatial period = 512 µm) were fitted with the von Mises function (Eq. 1; Oesch et al. 2005), the parameters of the function were estimated using maximum likelihood methods (Berens 2009), and the peak and full width at half height (fwwh) were computed (Eq. 2; Elstrott et al. 2008). Direction tuning curve shape was insensitive to increasing the temporal period of the drifting gratings to 2 s. Circular statistics were used to calculate the circular skewness of individual DS tuning curves and Rao’s spacing test for the nonuniformity of preferred tuning distribution (Berens 2009).

| (1) |

| (2) |

A is the maximum response, u is the preferred direction in radians and was determined by the vector sum of the normalized responses across the eight presented grating directions, and κ is the concentration parameter accounting for tuning width.

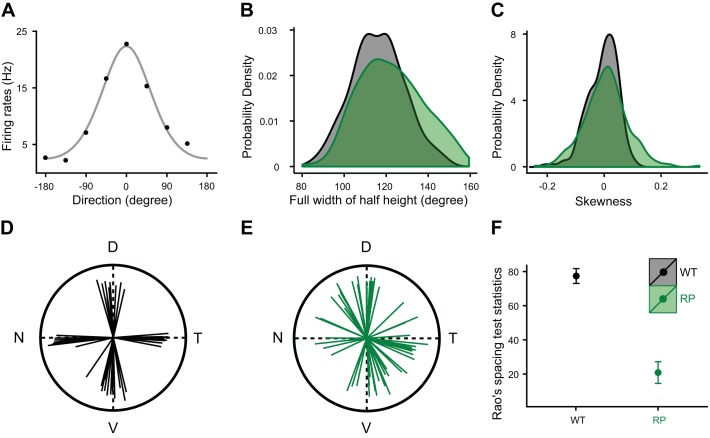

Fig. 9.

Direction tuning preferences are disrupted among DS-RGCs in S334ter-3 retina. A: direction tuning for a DS RGC from an S334ter-3 retina. Data points show average firing rates, and gray curve is a fitted von Mises function. B: distribution of tuning widths at half height for DS RGCs in WT (black) and S334ter-3 retinas (green). C: skewness distribution of tuning curves for DS RGCs in WT (black) and S334ter-3 retinas (green). D and E: directional preferences of DS cells in one WT (D) and one S334ter-3 retina (E). D, dorsal; T, temporal; V, ventral; N, nasal. F: homogeneity test for the distribution of preferred directions (mean and SE).

Statistical analysis.

Unless noted otherwise, the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test was used to compare WT and RP data sets, and significance was determined at P < 0.05; data are means ± SD. In Fig. 7, C, D, and F, linear regression was used to fit the data. All statistics were performed using R version 3.2.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing; https://www.R-project.org).

RESULTS

The primary goal of this study was to determine the impact of rod photoreceptor death on cone-mediated signaling among RGCs. First, we show RGC spatial RFs are irregular due to the reorganization of cones in this animal model of RP. Second, despite the nearly complete loss of rods, RGC types persist and can be matched to cell types in WT retinas. These RGC types exhibit a mosaic organization, indicating they correspond to morphologically distinct types. Third, we show both common and cell type-specific changes in the spatiotemporal RF structure, direction selectivity, and spontaneous activity caused by the loss of rods and reorganization of cones.

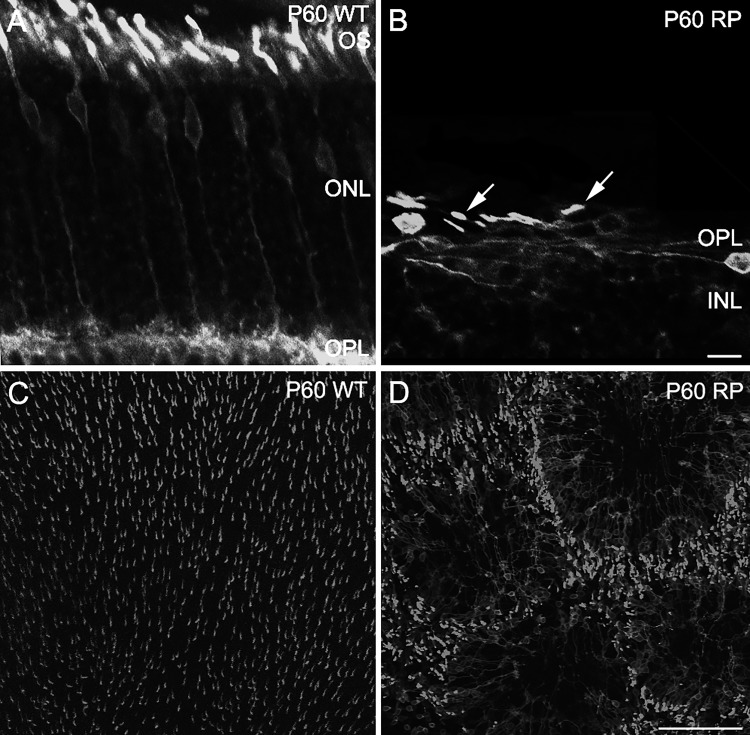

Photoreceptor remodeling leads to distorted RGC RFs.

S334ter-3 rats exhibit progressive photoreceptor degeneration that begins with rods and eventually leads to cone death (Ji et al. 2012; Liu et al. 1999). Most rods die by P30, whereas cone loss is minimal before P180 (Ji et al. 2012). Between rod and cone death, cones reorganize to form rings in the outer retina (Ji et al. 2012). To determine the extent of this reorganization at P60, the age at which RGCs were recorded in this study, WT and S334ter-3 retinas were immunolabeled for opsins. M-opsin immunoreactivity in WT animals revealed cones that were vertically aligned and homogeneously organized with uniform spacing across the retina, consistent with previous studies (Figs. 1, A and C; García-Ayuso et al. 2013; Ji et al. 2012). In contrast, M-opsin immunoreactivity in S334ter-3 retinas revealed that cones lost their vertical orientation, lying flat against the outer retina with shorter and distorted outer segments (Fig. 1B). Consistent with previous observations at P90 (Ji et al. 2012), the cones also exhibited a ring-like spatial organization, leaving large holes with few or no cones (Fig. 1D). A similar pattern was observed with S-opsin immunoreactivity (data not shown; Ji et al. 2012).

Fig. 1.

Remodeling of the cone mosaic in S334ter-3 RP rats at P60. A and B: confocal micrographs of vertical sections showing M-opsin immunoreactivity in WT (A) and S334ter-3 (RP) retinas (B). Cone outer segments (OS) are shorter and distorted (B, arrows). ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer. Scale bar, 10 μm. C and D: M-opsin immunoreactivity from confocal micrographs of whole mount retinas in WT (C) and S334ter-3 rats (D). C: homogeneous distributions of M-opsin-containing cones in WT retina. D: cones are organized into rings in S334ter-3 retina. Scale bar, 100 μm.

To determine the consequences of these structural changes on the spatial RFs of RGCs, we recorded WT and S334ter-3 rat retinas on a large-scale MEA while presenting visual stimuli (Anishchenko et al. 2010; Litke et al. 2004). Checkerboard noise stimuli were presented to estimate the spatiotemporal RFs of RGCs by computing the STA stimulus (Chichilnisky 2001). In WT retinas, the RFs of ON and OFF RGCs exhibited a Gaussian-like shape (Fig. 2A). In contrast, RFs from S334ter-3 retinas exhibited anomalous spatial structures; they tended to form arcs, partial rings, and sometimes complete rings (Fig. 2B). This structure was reminiscent of that observed in the cone mosaic (Fig. 1D). Indeed, when RFs of individual RGCs were summed together to generate a binary map of spatial sensitivity across the retina, the map revealed ring-like regions that were responsive to light that encircled large regions that were insensitive to light (Fig. 2D; see materials and methods). This functional map of light sensitivity reproduced the pattern exhibited by the cone outer segments in S334ter-3 retinas (Fig. 2D, inset). In comparison, the maps of spatial sensitivity did not exhibit ring-like patterns in WT retinas (Fig. 2C).

To determine whether anatomical holes in the cone mosaic and functional holes in RGC light sensitivity matched in size, we compared the diameters of rings observed anatomically and functionally by fitting each ring with an ellipse. The mean diameter of these ellipses (geometric mean of the major and minor axes) was not significantly different between anatomical and functional rings (anatomical rings: 274 ± 66 µm; physiological rings: 243 ± 72 µm; P = 0.3204).

The regions in S334ter-3 retinas with little to no light sensitivity were not caused by a failure to record from RGCs in those regions. The total number of recorded RGCs (classified and unclassified) in each WT and S334ter-3 experiment was not significantly different (WT: 291 ± 28, n = 4; RP: 350 ± 18, n = 5; P = 0.1905), indicating that the efficiency of recording from RGCs was similar in S334ter-3 and WT retinas. In addition, estimates of RGC soma locations from the electrical images of recorded RGCs (see materials and methods) indicated that total RGC density was unchanged in areas with low visual sensitivity in S334ter-3 retinas (low sensitivity: 551 ± 51 cells/mm2, whole area: 556 ± 47 cells/mm2, n = 5; P = 0.8413; Chan et al. 2011). Therefore, the gaps in light sensitivity in the recorded retinas were caused by the reorganization of cones into rings.

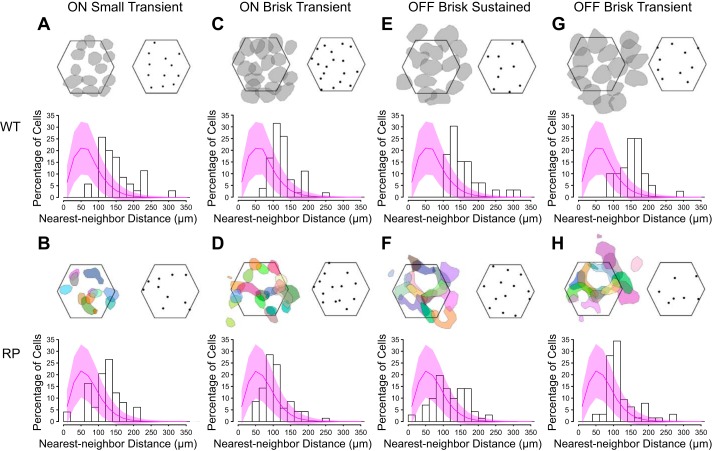

Functionally distinct RGC types remain after rod death.

The results of Figs. 1 and 2 demonstrate a structural and functional reorganization in the outer retina, caused by rod death and cone reorganization. To determine the consequences of these changes on the many functionally diverse RGC types in the mammalian retina necessitates a cell type-specific analysis (Della Santina et al. 2013; Ou et al. 2015; Sanes and Masland 2015; Yee et al. 2014). Therefore, we first establish a method for functionally classifying RGCs from these MEA recordings and show that functionally distinct RGC types persist after the loss of nearly all rods.

A semi-supervised classification of RGCs based on their light responses was applied to WT retinas (Fig. 3, A–D and I–L; see materials and methods). RGCs were classified in a serial manner, in which a distinct type was isolated from all other RGCs at each step in the classification. This approach allowed ~40% of RGCs in WT retinas to be classified into distinct types (Fig. 3, A–D and I–L; WT: 42.2 ± 1.4%, RP: 42.4 ± 1.4%). Specifically, we identified ON-OFF DS RGCs, functionally symmetric pairs of ON and OFF brisk sustained cells, ON and OFF brisk transient cells, ON and OFF small transient cells, and finally, OFF sluggish RGCs. To validate the output of this classification, each identified type exhibited an approximate tiling of RFs over space and regular spacing of RGC locations (Fig. 4, A, C, E, and G). These features indicate that each functionally defined type corresponds to a morphologically distinct RGC type, because they also exhibit regularly spaced cell bodies and approximate tiling between neighboring dendritic fields (Dacey 1993; Vaney 1994; Wässle et al. 1981). Additionally, this tiling arrangement of RFs indicates that each RGC type could not be further subclassified (Devries and Baylor 1997; Field et al. 2007).

Fig. 4.

RGCs exhibited regular spacing within identified types in WT and S334ter-3 retinas. A, top left: RF contours for ON ST RGCs in one WT retina recording. Contours are drawn at 60% of RF peak. Hexagon indicates the outline of the electrode array. Top right, RGC locations estimated from the electrical image of each cell. Only cells with locations well estimated by the electrical image are plotted. Bottom, histogram of nearest-neighbor distances cumulated over 4 recordings. The magenta curve is the nearest-neighbor distribution of randomly sampled RGC locations (across all RGC types) measured across recordings; shaded area is the SD. B: same as A, but for ON ST RGCs identified in S334ter-3 retina. RF contours (B, top left) are drawn at 40% of peak RF and distinctly colored to aid in the visualization of their shapes. C and D, E and F, G and H: same as A and B, but for ON BT, OFF BS, and OFF BT RGCs, respectively, from WT and S334ter-3 recordings. RF contours are drawn at 60% of peak for all WT data (A, C, E, and G) and at 40% for all RP data (B, D, F, and H). MEA is 450 µm across from the left and right hexagon corners.

We used the identical classification approach to reveal functionally distinct RGC types in S334ter-3 retinas (Fig. 3, E–H and M–P). Specifically, each classification space that identified an RGC type in WT retinas, also identified an RGC type in S334ter-3 retinas. To check that RGC types identified in S334ter-3 retinas corresponded to morphologically distinct RGC types, their spacing was analyzed (Fig. 4, B, D, F, and H; Dacey 1993; Vaney 1994; Wässle and Riemann 1978). RGC locations were estimated by the location of their electrical signals on the MEA. Note that these locations were not fixed to the grid of electrodes; thus regular electrode spacing did not enforce regular RGC spacing (see materials and methods). The distribution of nearest-neighbor distances (NNDs) for RGC locations indicated that they were not consistent with a random distribution (Fig. 4, B, D, F, and H, histograms). Specifically, the dearth of short distances supported the existence of an exclusion zone around each RGC within a type, but not across types (Fig. 4, magenta curves). In addition, the clear peaks in each NND distribution indicates a tendency toward regular spacing. This suggests these functionally defined RGC types corresponded to morphologically distinct types. Note that the cone reorganization disrupted the spatial structure of individual RFs and thus also disturbed the tiling of neighboring RFs in S334ter-3 retinas (Fig. 4).

Although the total number of cells in each type varied across preparations, the functional classification of RGCs in WT and S334ter-3 retinas was consistent (Table 1). Seven types of RGCs emerged in WT and S334ter-3 retinas in addition to four types of ON-OFF DS RGCs (one type for each cardinal direction; data not shown).

Table 1.

Number of cells identified for each RGC type in WT and RP retinas

| Retina | Total | DS | ON BS | ON BT | ON ST | OFF BS | OFF BT | OFF ST | OFF Sluggish |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT1 | 252 | 44 | 4 | 15 | 5 | 9 | 14 | 8 | 0 |

| WT2 | 238 | 44 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 11 |

| WT3 | 317 | 51 | 15 | 18 | 14 | 13 | 16 | 12 | 5 |

| WT4 | 356 | 62 | 13 | 19 | 12 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 0 |

| RP1 | 369 | 54 | 16 | 21 | 16 | 15 | 22 | 6 | 14 |

| RP2 | 411 | 63 | 23 | 15 | 7 | 27 | 24 | 2 | 0 |

| RP3 | 309 | 50 | 13 | 6 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 10 |

| RP4 | 341 | 59 | 12 | 17 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 21 |

| RP5 | 324 | 37 | 8 | 23 | 14 | 13 | 10 | 13 | 14 |

Data are the number of cells identified for each RGC type in 4 WT and 5 S334ter-3 RP retinas. The total number of recorded RGCs (classified + unclassified) is 1,163 and 1,754 in WT and RP, respectively. The percentage of cells identified in each RGC type was not significantly different between WT and S334ter-3 except for OFF sluggish cells (1.5 ± 1.1% and 3.5 ± 1.0%, P = 0.003, WT and S334ter-3, respectively).

Matching RGC types between WT and S334ter-3 retinas.

To determine how rod death and the reorganization of cones impacts different RGC types, they must be matched between WT and S334ter-3 retinas. We matched RGC types on the basis of their classification order. The validity of this matching is supported by four lines of evidence. The first line of evidence is that the parameter spaces used to identify each RGC type in WT and S334ter-3 retinas were identical (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the distributions of RGCs in these parameter spaces were similar between WT and S334ter-3 animals (e.g., compare Fig. 3A with 3E, 3B with 3F, and so on). This suggests that although rod death perturbed RGC function, these perturbations were relatively small compared with the functional distinctions between RGC types.

The second line of evidence is based on matching cell types by the dynamics of their temporal RFs (Fig. 5, A–D). RGC temporal RFs indicate how visual input is integrated in time; they were estimated from the STAs (see materials and methods). To choose the best matching between RGC types in WT and S334ter-3 retinas, a minimal mapping algorithm was applied to the average temporal RF of each RGC type; DS RGCs were not included in this analysis. This algorithm finds the set of matches between elements from two conditions that are most similar (see materials and methods; Grzywacz and Yuille 1988; Ullman 1979). The minimal mapping algorithm indicated that the best matching was the same as that indicated by the classification order. This result supports the conclusion that RGC types were correctly matched between WT and S334ter-3 retinas.

The third line of evidence is based on matching RGC types by their responses to full-field light steps (Fig. 5E). This response feature provided a more independent matching than the previous two lines of evidence because full-field light steps were 1) not used in the classification and 2) the responses to this stimulus were not well predicted by temporal RF dynamics; full-field light steps stimulate center and surround simultaneously, engaging RF nonlinearities (Sagdullaev and McCall 2005). The responses to full-field light steps were summarized by generating a PSTH. These histograms were averaged across cells of a type. The best matching was identified by the minimum mapping algorithm applied to these histograms (Fig. 5E; see materials and methods). The matching of cell types by this method was identical to the two previous methods.

The three previous lines of evidence were all based on responses to visual stimuli. However, rod death and the reorganization of cones may cause the response properties of one RGC type to mimic those of another. Thus the fourth line of evidence is based on spike shape, an intrinsic neuronal property. If photoreceptor degeneration minimally perturbs ion channel expression patterns among RGCs, then the spike shapes of each RGC type should be similar within types and different across types for WT and S334ter-3 retinas. To test this, the spike shape for each RGC type was estimated by averaging the extracellularly recorded spike waveforms across all cells of a type in each recording (see materials and methods). This analysis was limited to non-DS RGCs. The mean spike shapes revealed subtly different dynamics across cell types and in S334ter-3 retinas (Fig. 6, A, B, D, and E).

To determine whether these differences were systematically preserved across healthy and S334ter-3 retinas, PCA was used to identify a subspace for viewing the spread in spike shapes across recordings (Fig. 6, C and F). For the three ON cell types, spike waveforms clustered by type in a subspace defined by the first two principal components (Fig. 6C; filled symbols are RP recordings). The first principal component separated ON brisk sustained cells, whereas the second component separated brisk transient from small transient cells. For the four OFF RGC types, spike waveforms clustered by types in a subspace defined by the first three principal components (Fig. 6F). When the OFF sluggish cells were omitted from the classification, PCA yielded a clustering of the OFF brisk sustained, brisk transient, and small transient cells similar to that produced by the corresponding ON RGC types (Fig. 6F, inset). Therefore, spike shapes were consistent between WT and S334ter-3 retinas within RGC types and systematically different across types. This further supports the conclusion that RGC types were correctly matched between WT and S334ter-3 retinas.

To summarize, the classification parameter spaces, the temporal RFs, responses to full-field light steps, and spike shapes all indicated the same matching of RGC types between WT and S334ter-3 retinas. This indicates that RGC types persisted and could be analyzed independently after rod death and the reorganization of cones.

Rod death and cone reorganization alters RF size and shape.

The distributions of spatial RF sizes and shapes summarize the resolution and regularity with which visual scenes are sampled by RGCs. Changes in the size or shape of spatial RFs indicates altered visual signaling. We therefore determined how the size and shape of cone-mediated spatial RFs were altered by rod death in specific RGC types. This analysis led to three conclusions: 1) the distribution of RF shapes changed uniformly across all examined RGC types; 2) the larger variation in RF shape among RGCs from S334ter-3 animals was consistent with the reorganization of cones; and 3) RGC types with larger spatial RFs exhibited larger changes in RF size than those with smaller spatial RFs.

To analyze changes in RF shape, a convexity index was computed for the spatial RFs of each RGC (Fig. 7, A and B). High indexes correspond to approximately Gaussian-shaped RFs, whereas arc-like RFs will have low indexes. In WT retinas, convexity index values were close to 1, on average, and the distributions of convexity indexes were similar for all types examined (Fig. 7B, distributions in black). In contrast, S334ter-3 retinas exhibited distributions of convexity indices, with lower mean values (Fig. 7B, distributions in green). The distributions were similar across RGC types in S334ter-3 retinas, indicating that rod death had a similar impact on RF shape across cell types.

The distribution of convexity indexes in S334ter-3 also exhibited higher variance than in WT (Fig. 7B), indicating that some individual RGCs were impacted by rod death and the reorganization of cones more than others. A possible explanation is that RGCs located near the center of a hole in the cone mosaic receive input from many cones that moved to the rim of a ring. These RGCs would exhibit non-convex RF shapes, such as arcs. In contrast, RGCs located near the rim of a ring may receive input from cones that migrate less far, and the RFs of these RGCs will remain more Gaussian. To test this possibility, the relationship between RF shape and RF displacement was compared for each RGC (Fig. 7,C and D). RF displacement was estimated as the median distance from the RF center of mass to the RGC location (as estimated from the electrical image of the RGC; see materials and methods). Convexity indexes and RF displacements were negatively correlated in S334ter-3 retinas (Fig. 4D; r2 = 0.23, β = −141.4, P < 0.00001), but not in WT retinas (Fig. 4C; r2 = 0.002, β = −33.6, P = 0.4947). This analysis indicates that changes in cone-mediated RF shape are largely due to the reorganization of cones.

Finally, we found that RGCs with larger RFs exhibited greater changes in size compared with those with smaller RFs. Spatial RF sizes were computed for each RGC type in WT and S334ter-3 retinas (see materials and methods). Consistent with previous studies (Hammond 1974; Heine and Passaglia 2011; Petrusca et al. 2007), RF size depended strongly on RGC type (Fig. 7E). OFF brisk transient RGCs had the largest RFs, whereas OFF sluggish RGCs had the smallest (Fig. 7E). In S334ter-3 retinas, RF sizes decreased significantly in all types relative to WT (P < 0.00001 for all the types). However, their relative order (largest to smallest) was maintained (Fig. 7E). Moreover, the shrinkage of the mean RF was proportional to its size (Fig. 7F; r2 = 0.91, P = 0.002). Therefore, whereas changes in spatial RF shape were largely independent of cell types, changes in RF size were cell type dependent.

Rod death prolongs temporal integration of RGCs.

Just as each RGC type has a distinct spatial RF, each type integrates visual signals with distinct temporal dynamics. These dynamics determine the range of temporal frequencies that readily drive responses in RGCs. Human patients with RP exhibit diminished temporal vision becoming less sensitive to high temporal frequencies (Dagnelie and Massof 1993), which may be explained by changes in RGC temporal RFs. Therefore, we determined how temporal RF dynamics were affected by rod death (Fig. 8).

For all non-DS RGC types, the dynamics of the temporal RF was slower (exhibited prolonged temporal integration) in S334ter-3 than in WT retinas (Fig. 8A; P < 0.0001 for all types). For a quantitative comparison, the temporal RFs were fit with a difference of low-pass filters, and three features were extracted from these fits: time to peak, time to zero-crossing, and degree of transience (DoT; Fig. 8A, top right).

The time to peak of the temporal RF corresponds to response latency (Chichilnisky and Kalmar 2002; Field et al. 2007). Analysis of the time to peak indicated that rod death leads to increased response latencies among all RGCs, but the magnitude of the change depends on RGC type (Fig. 8B; P < 0.0001 for all types). Specifically, in S334ter-3 retinas, the mean time to peak was delayed 36 ms compared with WT. OFF sluggish RGCs exhibited the largest change (42 ms, 29.3%), whereas OFF small transient RGCs exhibited the smallest change (25 ms, 25.2%).

Time to zero-crossing of the temporal RF is related to the time of maximum firing rate in response to a step in light intensity (Field et al. 2007). Similar to the time to peak, all RGC types in S334ter-3 retinas had longer times to zero-crossing than those in WT (Fig. 8C; P < 0.0001 for all types). The mean time to zero-crossing was delayed 67 ms compared with WT. However, the magnitude of the delay depended on RGC type, with the OFF brisk sustained RGCs being affected the most (95 ms, 75.8%) and OFF brisk transient RGCs the least (32 ms, 21.0%; Fig. 8C).

DoT quantifies the biphasic nature of the temporal RF and indicates whether the temporal filtering of visual input is low pass or bandpass (e.g., a high biphasic index indicates strongly bandpass temporal integration). The impact of S334ter-3 on DoT depended on RGC type (Fig. 8D; P = 0.6743 for OFF sluggish, P = 0.4402 for OFF brisk transient, and P < 0.0001 for all other types). In particular, OFF small transient RGCs became less biphasic, whereas ON small transient, OFF brisk sustained, and ON brisk sustained cells became more biphasic; the DoT of OFF sluggish and OFF brisk transient cells did not change significantly.

These results indicate that rod degeneration generally prolonged the temporal integration of RGCs. However, the magnitude of prolongation and changes in the dynamics of temporal integration depended on RGC type.

Impact of rod death on DS RGCs.

DS RGCs signal visual motion to the brain (Barlow and Hill 1963; Grzywacz and Amthor 1993; Oyster and Barlow 1967; Vaney et al. 2012). They are likely important for the optokinetic reflex and may play a role in shaping cortical motion processing (Cruz-Martín et al. 2014; Yoshida et al. 2001). Furthermore, direction selectivity is the result of a precisely wired circuit within the retina (Briggman et al. 2011; Demb 2007; Ding et al. 2016; Hoggarth et al. 2015). Therefore, changes in DS RGC function induced by rod death may provide a “canary in the coal mine” for observing perturbations to retinal circuits and may be predictive of behavioral deficits related to motion processing.

We first tested whether DS RGCs persisted after the death of rods and reorganization of cones. The reorganization of the outer retina did not significantly decrease the proportion of RGCs identified as direction selective in S334ter-3 retinas compared with WT (WT: 17.4 ± 0.5%; RP: 15 ± 1.0%; Pearson’s chi-square test: χ2 = 2.5698, df = 1, P = 0.1089). This indicates that rod death and cone reorganization do not cause a rewiring in the inner retina that eliminates direction selectivity.

To test for more subtle changes in DS RGC function, the shape of their direction tuning functions were compared between S334ter-3 and WT retinas (Fig. 9, A–C). DS RGC tuning curves were measured using square-wave gratings that were drifted in eight directions (see materials and methods). Tuning curves were broader in S334ter-3 retinas, indicating that individual cells were less precisely direction tuned (Fig. 9B; 1-tailed Mann-Whitney test, P = 0.0013). To test for changes in tuning curve symmetry, the circular skewness of the tuning curve was calculated for each DS RGC (see materials and methods). The distribution of these skewness values was broader in S334ter-3, indicating more DS RGCs with asymmetric tuning curves (Fig. 9C; WT: −0.005 + 0.05; RP: 0.001 + 0.09; 2-tailed F-test, P < 0.0001). These analyses suggest that cone reorganization may disrupt the precision and regularity of DS RGC tuning. A change in the temporal integration of DS RGCs, like that observed for non-DS RGCs (Fig. 8), may also contribute to changes in direction tuning width. However, this is unlikely to fully explain these observations because the expected change in temporal integration (~50%, as estimated from non-DS-RGCs in Fig. 8) is much less than the increase in the temporal period of drifting gratings (~400%) required to match the increase in tuning width observed in DS RGCs (data not shown).

If the tuning of individual DS-RGCs is perturbed by the reorganization of cones, this suggests that the direction preferences among populations of DS-RGCs may no longer lie along four cardinal directions (Elstrott et al. 2008; Oyster and Barlow 1967). We measured the direction tuning across populations of simultaneously recorded DS RGCs in WT and S334ter-3 retinas. In WT retinas, population tuning preferred four cardinal directions (Fig. 9D). In S334ter-3 retinas, population tuning appeared less organized (Fig. 9E). A statistical analysis of the distribution of preferred directions across the population of DS RGCs confirmed greater disorder in S334ter-3 than WT retinas (Fig. 9F; P = 0.0159; see materials and methods). However, Rao’s spacing test of uniformity also indicated that the distribution of preferred directions was not random (P < 0.05), suggesting that some residual bias for the original cardinal axes persisted.

These results indicate that for individual and populations of DS RGCs, rod death did not eliminate direction selectivity under photopic conditions. However, the reorganization of cones likely disrupted the direction tuning of individual cells and led to spurious direction tuning away from the cardinal axes (see discussion). Note that ON DS RGCs were not distinguished from ON-OFF DS RGCs. However, nearly all (95%) recorded DS RGCs exhibited OFF responses to decrements of light (data not shown), suggesting that most were ON-OFF DS RGCs.

Spontaneous activity is elevated in many but not all types of RGCs.

The spontaneous activity of RGCs defines the spiking activity on which light-driven signals must be detected (Barlow and Levick 1969; Copenhagen et al. 1987; Mastronarde 1983). Increases in spontaneous activity generally signify a decreased signal-to-noise ratio for stimuli near detection threshold. Therefore, to fully understand the functional consequences of rod death on RGC signaling, it is necessary to determine the impact on spontaneous activity (Margolis and Detwiler 2011; Stasheff 2008).

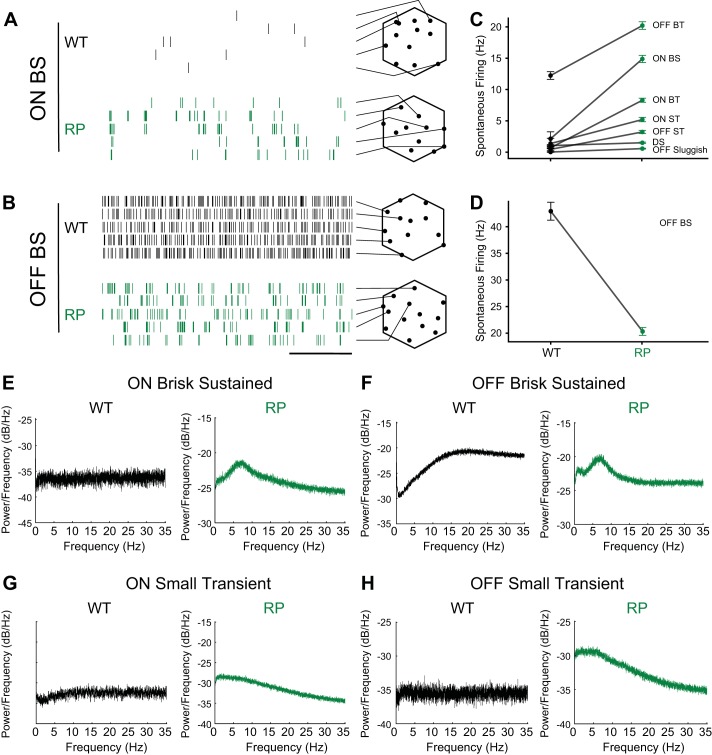

We found that the impact of rod death on the spontaneous activity of RGCs depended on cell type. Spontaneous activity was measured using a static and uniform “gray” screen presented at a photopic light level (see materials and methods). Most RGC types exhibited higher spontaneous firing rates in S334ter-3 (Fig. 10, A and C), consistent with previous results (Dräger and Hubel 1978; Euler and Schubert 2015; Fransen et al. 2015; Stasheff 2008). On average, classified RGCs exhibited a significant increase in spontaneous activity from 7.56 ± 0.79 Hz (n = 319) to 8.54 ± 0.33 Hz (n = 672; P < 0.0001, 1-way Mann-Whitney test), and unclassified RGCs exhibited an increase from 4.29 ± 0.30 Hz (n = 334) to 7.26 ± 0.27 Hz (n = 811; P < 0.0001, 1-way Mann-Whitney test). However, the fractional increase in spontaneous activity differed between types (Fig. 10C; P = 0.006 for OFF sluggish cells and P < 0.0001 for all other types). OFF brisk sustained RGCs exhibited a twofold reduction in spontaneous activity (Fig. 10B, raster plot; Fig. 10D, WT: 42.9 ± 1.7 Hz, n = 37; S334ter-3: 20.3 ± 0.7 Hz, n = 81; P < 0.0001). Therefore, in at least one RGC type, spontaneous activity decreases following rod death and before cone death.

Fig. 10.

Changes in spontaneous activity in S334ter-3 retinas are RGC type dependent. A: spontaneous firing for ON BS RGCs from WT and S334ter-3 (RP) retinas. Each row shows spike times for a different RGC recorded simultaneously (scale bar, 500 ms). Array outlines (hexagons) show estimated soma locations of recorded RGCs (black points), and lines point to the corresponding row of the raster. B: same as A, but for OFF BS RGCs. C: mean spontaneous firing rates for 7 types of ganglion cells (means ± SE). D: mean spontaneous firing rates for OFF BS RGCs (means ± SE). E and F: power spectra of the spontaneous spiking for ON BS RGCs (E) and OFF BS RGCs (F) from WT and S334ter-3 retinas. G and H: power spectra of the spontaneous spiking for ON and OFF ST RGCs from WT and S334ter-3 retinas.

In addition to changes in the mean firing rate, photoreceptor death can induce oscillatory activity among RGCs (Biswas et al. 2014; Borowska et al. 2011; Euler and Schubert 2015; Fransen et al. 2015; Margolis et al. 2014; Menzler and Zeck 2011; Stasheff 2008; Yee et al. 2012). This oscillatory activity may also disrupt visual signaling. To determine whether different RGC types exhibited increased oscillatory activity before cone death, a power spectral analysis of the spontaneous activity was performed (Fig. 10, E–H). This analysis revealed weak rhythmic activity at ~7 Hz among ON and OFF brisk sustained, OFF brisk transient, and ON small transient RGC types in S334ter-3 but not WT retinas (Fig. 10, E and F). This is weaker than, but generally consistent with, oscillatory activity observed after the loss of both rods and cones (Borowska et al. 2011; Yee et al. 2012). In other RGC types such as ON and OFF small transient cells, the power spectral analysis revealed greater power at frequencies <5 Hz than at higher frequencies (Fig. 10, G and H). Thus changes in both firing rates and the dominant spiking frequencies were RGC type dependent.

DISCUSSION

Neural circuits throughout the brain are composed of many cell types. Learning how degeneration of one type impacts other types in these circuits will provide a greater understanding of the progression of these diseases and may point toward novel therapeutic approaches. In this study, we measured the net effect of rod death on cone-mediated RFs and light responses of many RGC types. We observed some changes that were ubiquitous across RGC types and some changes that were cell type dependent. Below, we comment on the mechanisms that may underlie the observed changes in RFs and RGC physiology, we comment on RGCs that were not functionally classified in this study, and we discuss some implications of this study for treating RP.

RF changes: implications and potential mechanisms.

RGC spatial RFs frequently exhibited arc-like shapes in S334ter-3 retinas (Fig. 7). These perturbations in the spatial RFs of individual cells also had consequences at the population level by disrupting the mosaic-like arrangement of RFs with homotypic neighbors (Fig. 4). These changes at both the single cell and population level can be explained largely, if not entirely, by the reorganization of cones (Figs. 1 and 2). Functionally, the cone reorganization introduced blind spots and locations with high cone density, which were reflected in the spatial RFs of the RGCs. We also observed a nearly linear relationship between the reduction in RF size in S334ter-3 retinas and RF size in WT retinas (Fig. 7F): cell types with larger spatial RFs exhibited larger reductions in RF size in S334ter-3 animals. This can be explained by noting that the reorganization of cones decreases their nearest neighbor spacing, effectively decreasing the retinal area sampled by the cone mosaic. This manifests as a shrinking in the area sampled by the spatial RFs. Larger RFs sample from more cones and thus shrink more because they are subject to a decreased inter-cone spacing that propagates across more cones. Functionally, these changes in RF size increase the mean and decrease the range of spatial frequencies that strongly drive RGC spiking.

The mechanisms causing changes in the temporal RFs are less clear. Although the temporal dynamics were slower for all RGCs in S334ter-3 retinas, the degree of change depended on type (Fig. 8). Thus common and distinct mechanisms could be involved. A possible common mechanism is compromised cone health, which could slow their responses; rod death has been observed to compromise cone function by producing toxic byproducts and loss of trophic support (Léveillard et al. 2004; Mohand-Said et al. 1997, 1998; Steinberg 1994). Another possible common mechanism is a reduced cone collecting area for light, which would effectively dark-adapt the cones; the response dynamics of cones are slower at lower light levels (Baylor et al. 1974, 1987). Cone outer segments were shorter and flattened in S334ter-3 retinas (Fig. 1; Ji et al. 2012), which likely reduces their effective collecting area (Baylor and Fettiplace 1975; Baylor and Hodgkin 1973; Sandberg et al. 1981). Rod death during retinal development may also impact all retinal pathways (Cuenca et al. 2004, 2005; Martinez-Navarrete et al. 2011; Ray et al. 2010; Strettoi et al. 2003). Rod loss can perturb postnatal maturation of cone pathways (Banin et al. 1999), and light responses of RGCs are slower at the time of eye opening than in adult rats (Anishchenko et al. 2010).

A possible pathway specific mechanism is differential changes in synaptic transmission between cones and different cone bipolar cell types. Glutamate receptor expression on bipolar cells is reduced and mislocalized with photoreceptor degeneration (Martinez-Navarrete et al. 2011; Puthussery et al. 2009; Strettoi et al. 2003). This could generate a slower bipolar cell response with differential effects among different bipolar cell types. Further experiments are needed to distinguish between common and pathway-specific mechanisms.

The spatiotemporal RFs of RGCs have also been examined in P23H-1 rats using approaches similar to those used here to study S334ter-3 rats (i.e., checkerboard noise stimuli and MEA recordings; Sekirnjak et al. 2011). Both P23H-1 and S334ter-3 rats have mutations in the gene encoding for rhodopsin. In P23H-1, the mutation causes a misfolding of the protein; in S334ter-3, the mutation results in a truncated COOh terminus that likely leads to improper protein trafficking (Liu et al. 1999; Martinez-Navarrete et al. 2011). P23H-1 animals exhibit a slower time course of rod photoreceptor death than S334ter-3, but both lines exhibit photoreceptor loss during development. Significant cone loss is observed before all rods have died in P23H-1 rats (García-Ayuso et al. 2013); therefore, the two lines exhibit distinct dynamics in rod and cone death. Despite these differences, both lines exhibit rings of cones surrounding regions with few or no photoreceptors (García-Ayuso et al. 2013; Ji et al. 2012). Average spatial RF size decreased and temporal integration increased in P23H-1 rats as photoreceptors died. These effects are qualitatively consistent with those reported in the present article. However, the spatial RFs in P23H-1 rats were not reported to exhibit arc-like shapes. One possible explanation for this difference is that in those experiments, the spatial resolution of the RF measurements was 4 to 16 times courser in area. This lower resolution could have blurred abnormal spatial RFs, causing them to appear more Gaussian.

Mechanisms altering tuning of direction selective RGCs.

Anatomical measurements indicate that DS RGCs are ~15–20% of all RGCs in rat (Sun et al. 2002), consistent with the fraction RGCs identified as DS in this study. These cells receive input from precisely wired presynaptic circuits to respond selectively to motion direction regardless of stimulus polarity (Barlow and Hill 1963; Grzywacz and Amthor 1993; Lee et al. 2012; Trenholm et al. 2011). DS RGCs are likely important for gaze stabilization, calibration of the vestibular system, and motion perception (Vaney et al. 2012). Therefore, understanding the impact of rod death on these cells is important for interpreting visual deficits measured behaviorally.

Rod death led to a broadening of DS tuning among individual RGCs and diminished the population preferences for the cardinal axes (Fig. 9). One possible explanation for these observations is that the reorganization of cones changed the direction and broadened the tuning of individual DS RGCs. A second possibility is that rod death caused a rewiring in the inner retina that altered DS RGC tuning. However, the extent of inner retinal remodeling is limited by the observation that RGCs with DS responses were not eliminated by rod death; a similar proportion of DS-RGCs were recorded in WT and S334ter-3 retinas. A third possible explanation is that retinal development was altered by rod death. The fine-tuning of DS circuits depends on visual experience (Bos et al. 2016; Chan and Chiao 2013; Chen et al. 2009; Elstrott et al. 2008; Tian and Copenhagen 2003); thus altered photoreceptor function may interrupt this refinement. Further experiments are needed to determine the relative contributions of these potential mechanisms.

Cell type-specific changes in spontaneous activity.

Spontaneous spiking activity sets a baseline noise level against which signals near threshold must compete (Barlow and Levick 1969; Troy 1983). Changes in spontaneous activity can therefore strongly impact behavior and perception (Aho et al. 1988). We observed changes in spontaneous activity following rod death that were RGC type specific. Given that each RGC type signals different visual features to the brain, cell type-dependent changes in spontaneous activity predict that some visually guided behaviors may be more severely impacted by rod death than others. Further work to understand the relationship between different RGC types and behaviors in rodents (Yilmaz and Meister 2013; Yoshida et al. 2001) is needed to test rigorously this prediction.

Changes in spontaneous activity have been observed and studied in many animal models of RP (Choi et al. 2014; Dräger and Hubel 1978; Fransen et al. 2015; Margolis et al. 2008, 2014; Menzler and Zeck 2011; Pu et al. 2006; Sekirnjak et al. 2011; Stasheff 2008; Stasheff et al. 2011; Toychiev et al. 2013). Recent work has also indicated that these changes depend on RGC type (Sekirnjak et al. 2011; Yee et al. 2012, 2014). However, there are several differences between previous studies and the experiments described in the present study. Previous studies primarily classified RGCs according to morphological features or simple functional distinctions (e.g., ON vs OFF), and these classifications were not validated by checking whether cells of a given type exhibited a mosaic organization (Sekirnjak et al. 2011; Yee et al. 2012, 2014). Furthermore, these studies largely (but not exclusively) focused on time points after which all photoreceptors were lost. Our study provides a distinct yet complementary view. First, RGCs were classified functionally rather than morphologically. Second, large-scale MEA recordings allowed us to validate the classification by testing for a mosaic organization within each RGC type. Third, we focused exclusively on a time point at which the vast majority of rods were dead (99.99%) but cones persisted. We found that most RGC types exhibited elevated spontaneous activity, but the increase depended on cell type (Fig. 10, A and C). Furthermore, OFF brisk sustained RGCs exhibited a substantial reduction in spontaneous activity (Fig. 10, B and D).

The spontaneous activity of RGCs has been measured in P23H-1 rats (Fransen et al. 2015; Sekirnjak et al. 2011). OFF, but not ON, RGCs exhibited elevated spontaneous activity in that model. This effect on spontaneous activity is distinct from that observed in this study and reported in rd1 and rd10 mice (Margolis et al. 2014; Stasheff 2008; Stasheff et al. 2011; Yee et al. 2012). This suggests that different causes and trajectories toward photoreceptor loss can have different effects on retinal circuits and RGC function.

Oscillatory activity has also been noted in many animal models of RP (Borowska et al. 2011; Haq et al. 2014; Margolis et al. 2008; Menzler et al. 2014; Yee et al. 2014). Low-frequency oscillations (~1 Hz) appear to be driven by horizontal cells (Haq et al. 2014), whereas higher frequency oscillations (~7–14 Hz) appear to be driven by either a coupled network of ON cone bipolar cells and AII amacrine cells or by AII amacrine cells alone (Borowska et al. 2011; Choi et al. 2014; Euler and Schubert 2015; Margolis et al. 2014; Yee et al. 2012). The present results indicate that the higher frequency oscillations appear before cone death in S334ter-3 rats, but not in all RGC types. This may result from some RGC types receiving stronger direct or indirect input from the network of AII amacrine cells. Further experiments are needed to determine whether lower frequency oscillations may become more substantial at later stages of degeneration.

Unclassified RGCs.

In WT and S334ter-3 experiments, ~40% of recorded RGCs were successfully classified. The rodent retina contains 30–40 RGC types (Baden et al. 2016; Sanes and Masland 2015; Sümbül et al. 2014), and we distinguished just 11 types. Our limited ability to classify these remaining cells largely stemmed from recording from too few cells of a given type in a single experiment to reveal a mosaic arrangement of RGCs. Without this verification step, it is difficult to accurately make cell type-specific comparisons between control and disease conditions, which was the main objective of this study.

The trends of slower temporal RFs and irregularly shaped spatial RFs observed among classified RGCs were also observed among unclassified cells. However, because this comparison is not cell type specific, we cannot rule out the possibility that some RGC types exhibit opposite trends. Further technical developments to improve large-scale neural population recordings will likely allow for more complete cell type-specific comparisons between healthy and disease retinas. For example, more sophisticated spike-sorting algorithms (Marre et al. 2012; Prentice et al. 2011) may increase the number of identified neurons. More identified neurons may provide sufficient statistical power to classify more cell types. Cell yield may also be increased by using denser electrode arrays or Ca2+ imaging of neural activity (Baden et al. 2016). It is also possible that using additional visual stimuli would aid the identification of more RGC types. For example, some rodent RGC types exhibit strong surround suppression such that they only respond to stimuli localized to their RF center (Jacoby and Schwartz 2017; Zhang et al. 2012). These cells would be expected to respond poorly to full-field checkerboard noise and the drifting gratings used in this study. Therefore, developing more refined stimuli, recording technologies, and spike-sorting procedures will ultimately allow a more complete and cell type-specific view of retinal degeneration.

Implications for RP.

RP results from one of many possible gene mutations and leads to severe vision loss in humans (Bowes et al. 1990; Farber and Lolley 1974; Marc and Jones 2003; Rosenfeld et al. 1992). Regardless of the underlying genetic defect, the disease begins with the degeneration of rod photoreceptors, followed by the degeneration of cones and an eventual rewiring of the remaining retinal neurons (Jones et al. 2003; Jones and Marc 2005; Strettoi 2015).