Abstract

Protists kill their bacterial prey using toxic metals such as copper. Here we hypothesize that the metalloid arsenic has a similar role. To test this hypothesis, we examined intracellular survival of Escherichia coli (E. coli) in the amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum (D. discoideum). Deletion of the E. coli ars operon led to significantly lower intracellular survival compared to wild type E. coli. This suggests that protists use arsenic to poison bacterial cells in the phagosome, similar to their use of copper. In response to copper and arsenic poisoning by protists, there is selection for acquisition of arsenic and copper resistance genes in the bacterial prey to avoid killing. In agreement with this hypothesis, both copper and arsenic resistance determinants are widespread in many bacterial taxa and environments, and they are often found together on plasmids. A role for heavy metals and arsenic in the ancient predator–prey relationship between protists and bacteria could explain the widespread presence of metal resistance determinants in pristine environments.

Keywords: Protist, Grazing, Arsenic

Introduction

The Great Oxidation Event changed the bioavailability of many metals and metalloids and increased the concentrations of both copper and zinc but also arsenic but peaked at different time points (Chi Fru et al. 2015, 2016). Recent data show that at least some protists forage on bacteria using toxic metals such as copper and maybe zinc in their phagosomes (Hao et al. 2016). Dictyostelium discoideum (D. discoideum) as an ‘early’ macrophage shares several unique functions with mammalian phagocytic cells (Metchnikoff 1887). Since the basic mechanisms involved in phagocytosis appear extremely conserved, this unicellular soil amoeba could provide a better understanding of how bacteria can escape phagocytosis and intracellular killing by both amoeba and macrophages (Cosson and Soldati 2008). Here we propose a novel hypothesis that protists also use the metalloid arsenic to kill bacterial prey, thus, inducing a selective pressure for bacteria to become more resistant to arsenic.

Methods and materials

Intracellular bacteria survival in Dictyostelium

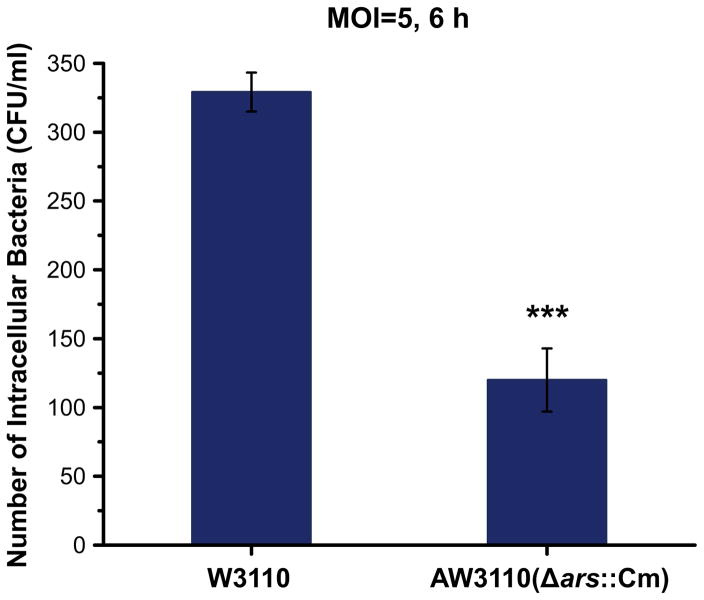

To test if arsenic resistance determinant could assist bacterial survival in amoeba, gentamicin (Gm) protection assays were performed as reported previously (Hao et al. 2015). Briefly, overnight growth of the wild type Escherichia coli (E. coli) W3110 and the arsenic sensitive mutant AW3110 (ΔarsRBC::Cm) (Carlin et al.) were harvested, rinsed and suspended in HL5:SorC (1:4) solution to A600 nm of 0.1 [approximately 108 colony-forming units (CFUs)/ml], respectively. A mid-exponential phase (1 × 106 cell/ml) culture of D. discoideum was prepared in HL5:SorC (1:4) solution. 900 μl of Dictyostelium cells was placed into 24-well polystyrene plates and mixed with bacteria to a final multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5. The mixture was cultured at 22 °C for 6 h, centrifuged (400×g; 2 min), and rinsed twice with 1 ml of SorC buffer. Dictyostelium cells were treated with 400 μg/ml Gm at room temperature for 1 h to remove extracellular bacteria. After two times of washing by SorC buffer, Dictyostelium cells were lysed in 1 ml SorC with 0.4% Triton X-100. 100 ml of lysates were plated on LB for CFU counting. Two sets of control were prepared as follows: (1) we set amoebal suspension (1 × 106 cell/ml, 900 μl) mixed with 100 μl of HL5:SorC (1:4) solution as negative control to make sure the initial amoebal cultures were free from bacteria, (2) we used 100 μl of bacterial suspension mixed with 900 μl of HL5:SorC (1:4) solution (without amoebae) to verify the efficiency of Gm. All assays were performed in at least six replicates.

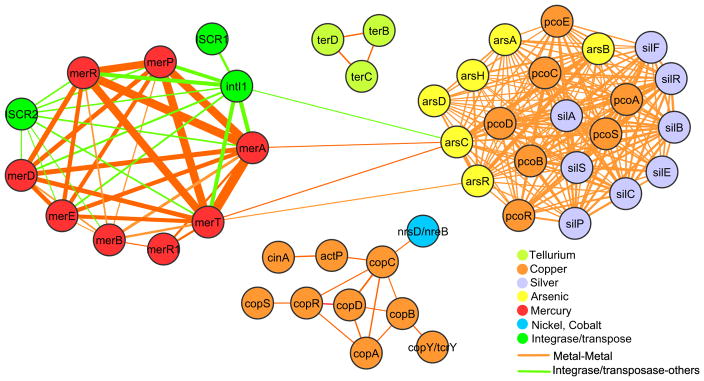

Co-occurrence network of metal resistance genes

To show the co-occurrence patterns between metal resistance genes that most frequently occur together on plasmids, publicly available completely sequenced plasmids (n = 4582) were retrieved from the NCBI plasmid genomes database (Acland et al. 2014) (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/Plasmids/). In addition, metal resistance protein sequences were retrieved from the BacMet predicted database (version 1.1; http://bacmet.biomedicine.gu.se) (Pal et al. 2014). A network showing the co-localization of resistance genes on the same plasmid, was developed, explored and visualized using Cytoscape (version 3.2.0) (Shannon et al. 2003). To avoid dense clustering of genes and show only the most common co-occurrences, the network was filtered on Cytoscape platform in such a way so that two genes (i.e., nodes) coexisted on at least ten plasmids were connected by a line (e.g., an edge). In addition to co-localization of resistance genes, resistance genes that frequently co-occur together with well-known integron-associated integrases or ISCR transposases was also shown (Pal et al. 2015).

Results and conclusions

In support of our hypothesis, we examined the intracellular survival of E. coli AW3110, a strain in which the ars operon had been deleted. We found that the intracellular survival of E. coli AW3110 in D. discoideum was significantly (two-sample t test, p < 0.0001) decreased as compared to the wild type strain (Fig. 1). Our data suggests that D. discoideum could use arsenic to kill the bacterial prey in the phagosome, which is inline with the copper and zinc poisoning of bacterial and fungi prey in the phagosome of macrophages (German et al. 2013) and D. discoideum (Hao et al. 2016). Notably, Cu(I) and As(III) are far more toxic than Zn(II) and if available would be a more toxic mix. It is known that Great Oxidation Event increased the concentrations of both copper and arsenic but peaking at different time points (Chi Fru et al. 2015, 2016). Therefore we suggest that arsenic and copper poisoning to be a potent weapon for protists, beginning after the onset of the Great Oxidation. Subsequently, it increased the bioavailability of both copper and arsenic for the primitive phagocytic eukaryotes. As a consequence, resistance genes to these metals frequently occur in bacteria, which help in evading bacterial killing by macrophages and protists via clustering resistances. Recently, it was hypothesized that metals get concentrated in endosomes “metallosomes” before merging with their phagosome, the location of bacterial killing (Kapetanovic et al. 2016). Nonetheless, so far zinc accumulation into vesicles has been observed (Kapetanovic et al. 2016). In addition, protist-grazing resistance as an important component in the evolution of bacterial pathogenesis has also been recognized (Amaro et al. 2015).

Fig. 1.

Arsenic resistance determinant arsRBC enhances bacterial survival in D. discoideum. Gentamicin (Gm) protection assay was carried out to test the number of intracellular bacteria within Dictyostelium. Dictyostelium (1 × 106 cell/ml, 0.9 ml) was seeded in 24-well polystyrene plates and mixed with the wild type E. coli W3110 and the arsenic sensitive mutant AW3110 (ΔarsRBC::Cm), respectively, to a MOI of 5. Mono-bacteria or Dictyostelium cells were set as control. The mixture was co-cultured for 6 h at 22 °C, washed twice with SorC, and treated with 400 μg/ml Gm for 1 h. Dictyostelium cells were washed twice with SorC after Gm treatment and lysed with 0.4% Triton X-100. Lysates (100 μl) were then plated on LB agar for CFU counting. All assays were performed in at least six replicates

Metal resistance genes are ubiquitous in bacterial communities across different environments and occur in many different phyla (Pal et al. 2015, 2016). Based on the analyses of 4582 fully sequenced plasmids, common occurrence of copper, arsenic and silver resistance genes have been reported (Fig. 2) (Pal et al. 2015). In our previous study, we revealed the fact that silver resistance determinants were actually copper resistance determinants. In fact, it is actually only copper and arsenic resistance determinants which are occurring together (Hao et al. 2015). A putative explanation for the joint appearance of resistance genes could be a response to selection pressure by protists, dating back more than two billion years. Protists, without harming themselves can utilize the most toxic Cu(I) and As(III), which are sufficiently bioavailable in the environment to be routinely used for poisoning bacterial and fungal prey. Bacteria carrying arsenic and copper resistance genes may also carry antibiotic resistance genes, providing opportunities for co-selection. While antibiotic resistance genes are considerably more common in isolates from human and domestic animals, i.e., where there often is a strong antibiotic selection pressure, metal resistance genes are common in a much wider set of environments (Pal et al. 2015). Consequently, co-selection by antibiotics is not the prime reason of widespread copper and arsenic resistance in bacteria. In fact, more ancient and widespread selection pressures are likelihood reasons for such resistance, and in line with our finding of heavy metal resistance genes across taxa (Pal et al. 2015) and metagenomes (Pal et al. 2016). This principally also excludes recent uses of heavy metals by humans, and thereby elevated exposure in some bacterial communities, as a major driving force. Nevertheless, recently introduced anthropogenic selection pressures including metals and antibiotics have the potential to propagate the spread of plasmids carrying multiple resistance determinants, also in pathogens. While arsenic resistance determinants have previously not been considered as a virulence factor, which is as also evident from earlier studies (Neyt et al. 1997; Tosetti 2014), many strains of Yersinia pestis and Yersinia enterolytica harbor plasmids containing an arsenic resistance operon arsHRBC (Eppinger et al. 2012). We postulate the presence of ars operons in Yersinia sp. is an adaptation to help the bacteria evade arsenic poisoning by protist grazing possibly with a role in bacterial virulence.

Fig. 2.

Co-occurrence of metal resistance genes on plasmids. The network depicts co-occurrences of metal resistance genes included in the BacMet database (Pal et al. 2014) on 4582 plasmids retrieved from the NCBI plasmids database (see Pal et al. 2015 for details). The thickness of each connection (i.e., edge) between two genes (i.e., nodes) is proportional to the number of times the genes co-occurred on the same plasmid. Connections are only shown if the genes are found together on at least 10 different plasmids. The network also includes connections between metal resistance genes and markers of mobile genetic elements (integron-associated integrases and ISCR transposases)

Acknowledgments

This Project was financially supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB15020402, XDB15020302), the International Postdoctoral Exchange Fellowship Program (No. 20150079), the Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agriculture and Spatial Planning (FORMAS), and the Centre for Sea and Society at University of Gothenburg. BPR was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM55425 and ES023779. Authors would like to thank Twasol Research Excellence Program (TRE Program), King Saud University, Saudi Arabia for support.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Xiuli Hao, Key Laboratory of Urban Environment and Health, Institute of Urban Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xiamen 361021, China.

Xuanji Li, Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Chandan Pal, Department of Infectious Diseases, Institute for Biomedicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Göteborg, Sweden. Center for Antibiotic Resistance Research (CARe) at the University of Gothenburg, Göteborg, Sweden.

Jon Hobman, School of Biosciences, The University of Nottingham, Sutton Bonington Campus, Sutton Bonington, Leicestershire LE12 5RD, UK.

D. G. Joakim Larsson, Department of Infectious Diseases, Institute for Biomedicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Göteborg, Sweden. Center for Antibiotic Resistance Research (CARe) at the University of Gothenburg, Göteborg, Sweden

Quaiser Saquib, Zoology Department, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. A.R. Al-Jeraisy Chair for DNA Research, Zoology Department, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Hend A. Alwathnani, Botany & Microbiology Department, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Barry P. Rosen, Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA

Yong-Guan Zhu, Key Laboratory of Urban Environment and Health, Institute of Urban Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xiamen 361021, China.

Christopher Rensing, Key Laboratory of Urban Environment and Health, Institute of Urban Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xiamen 361021, China. J. Craig Venter Institute, San Diego, CA, USA. Fujian Provincial Key Laboratory of Soil Environmental Health and Regulation, College of Resources and Environment, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China.

References

- Acland A, Agarwala R, Barrett T, Beck J, Benson DA, Bollin C, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro F, Wang W, Gilbert JA, Anderson OR, Shuman HA. Diverse protist grazers select for virulence-related traits in Legionella. ISME J. 2015;9:1607–1618. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Fru E, Arvestål E, Callac N, El Albani A, Kilias S, Argyraki A, et al. Arsenic stress after the Proterozoic glaciations. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17789. doi: 10.1038/srep17789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Fru E, Rodriguez NP, Partin CA, Lalonde SV, Andersson P, Weiss DJ, et al. Cu isotopes in marine black shales record the Great Oxidation Event. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:4941–4946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523544113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosson P, Soldati T. Eat, kill or die: when amoeba meets bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppinger M, Radnedge L, Andersen G, Vietri N, Severson G, Mou S, et al. Novel plasmids and resistance phenotypes in Yersinia pestis: unique plasmid inventory of strain Java 9 mediates high levels of arsenic resistance. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German N, Doyscher D, Rensing C. Bacterial killing in macrophages and amoeba: Do they all use a brass dagger? Future Microbiol. 2013;8:1257–1264. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao X, Luthje FL, Qin Y, McDevitt SF, Lutay N, Hobman JL, et al. Survival in amoeba—a major selection pressure on the presence of bacterial copper and zinc resistance determinants? Identification of a “copper pathogenicity island”. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:5817–5824. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6749-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao X, Luthje F, Ronn R, German NA, Li X, Huang F, et al. A role for copper in protozoan grazing—two billion years selecting for bacterial copper resistance. Mol Microbiol. 2016;102:628–641. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovic R, Bokil NJ, Achard ME, Ong CL, Peters KM, Stocks CJ, et al. Salmonella employs multiple mechanisms to subvert the TLR-inducible zinc-mediated antimicrobial response of human macrophages. FASEB J Off Publ Feder Am Soc Exp Biol. 2016;30:1901–1912. doi: 10.1096/fj.201500061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metchnikoff E. Sur la lutte des cellules de l’organisme contre l’invasion des microbes. Ann Inst Pasteur. 1887;1:321–336. [Google Scholar]

- Neyt C, Iriarte M, Thi VH, Cornelis GR. Virulence and arsenic resistance in Yersiniae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:612–619. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.612-619.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal C, Bengtsson-Palme J, Rensing C, Kristiansson E, Larsson DG. BacMet: antibacterial biocide and metal resistance genes database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D737–D743. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal C, Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DG. Co-occurrence of resistance genes to antibiotics, biocides and metals reveals novel insights into their co-selection potential. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:964. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2153-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal C, Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DG. The structure and diversity of human, animal and environmental resistomes. Microbiome. 2016;4:54. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0199-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosetti F. On arsenic and plague. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2014;59:1806–1808. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]