ABSTRACT

Hypoxic training is effective for improving athletic performance in humans. It increases maximal oxygen consumption (V̇O2max) more than normoxic training in untrained horses. However, the effects of hypoxic training on well-trained horses are unclear. We measured the effects of hypoxic training on V̇O2max of 5 well-trained horses in which V̇O2max had not increased over 3 consecutive weeks of supramaximal treadmill training in normoxia which was performed twice a week. The horses trained with hypoxia (15% inspired O2) twice a week. Cardiorespiratory valuables were analyzed with analysis of variance between before and after 3 weeks of hypoxic training. Mass-specific V̇O2max increased after 3 weeks of hypoxic training (178 ± 10 vs. 194 ± 12.3 ml O2 (STPD)/(kg × min), P<0.05) even though all-out training in normoxia had not increased V̇O2max. Absolute V̇O2max also increased after hypoxic training (86.6 ± 6.2 vs. 93.6 ± 6.6 l O2 (STPD)/min, P<0.05). Total running distance after hypoxic training increased 12% compared to that before hypoxic training; however, the difference was not significant. There were no significant differences between pre- and post-hypoxic training for end-run plasma lactate concentrations or packed cell volumes. Hypoxic training may increase V̇O2max even though it is not increased by normoxic training in well-trained horses, at least for the durations of time evaluated in this study. Training while breathing hypoxic gas may have the potential to enhance normoxic performance of Thoroughbred horses.

Keywords: hypoxia, treadmill exercise, V̇O2max

Hypoxic training is effective for improving athletic performance of not only endurance athletes but also athletes in comparatively short-duration sports [4, 7, 9, 10, 18]. It has been thought that one of the reasons why hypoxic training improves athletic performance is that it induces hypoxemia because arterial O2 tension is decreased as the fraction of inspired O2 is decreased. There is little known about hypoxic training in horses.

Thoroughbred horses are considered to be elite athletes because their mass-specific (per kg) maximal oxygen consumption (V̇O2max) is twice as high as that of elite human athletes. It has been reported that Thoroughbred horses experience severe hypoxemia when exercising at V̇O2max, with arterial O2 tension less than 75 mmHg [3, 14, 15, 22]. Therefore, we wonder if hypoxic training would be effective for increasing V̇O2max and the performance of well-trained Thoroughbred horses. We hypothesized that the V̇O2max of well-trained Thoroughbreds would increase with hypoxic training. We tested this hypothesis by evaluating the effects of hypoxic training on V̇O2max and associated variables of well-trained Thoroughbreds in which V̇O2max had not increased over 3 consecutive weeks of supramaximal treadmill training in normoxia when the horses trained twice per week.

Materials and Methods

The protocol for the study was reviewed and approved by the Animal Use and Care Committee and the Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of the Japan Racing Association’s Equine Research Institute, where the study was conducted. Veterinarians regularly inspected all horses used throughout this study and detected no lameness nor unsoundness in any of the horses during the experiment.

Horses

Five healthy Thoroughbreds (one male, three geldings, and one female, average age 7.0 ± 2.0 (SD) years, average weight 483 ± 24 kg) were studied. The horses trained on a treadmill by running up a 6% incline while breathing normoxic gas (inspired O2 fraction 0.2095) twice a week prior to hypoxic training. Following a warm-up (1.7 m/sec for 2 min and 3.5 m/sec for 3 min), the exercise protocol consisted of 2-min exercise intervals at 1.7, 4.0, 7.0, 10.0, 12.0, 13.0, and 14.0 m/sec until the horses could not maintain their position at the front of the treadmill with humane encouragement. On 3 other days, the horses walked at a speed of 7 km/hr for 1-hr in a walking machine; for the other 2 days of the week, the horses rested in their stalls.

Hypoxic training

For hypoxic training, we studied 5 horses in which V̇O2max had not increased during the 3 prior consecutive weeks of supramaximal treadmill training in normoxia. The horses ran up a 6% incline while breathing hypoxic gas twice a week for 3 weeks. On 3 other days, the horses walked at a speed of 7 km/hr for 1 hr in a walking machine; for the other 2 days of the week, the horses rested in their stalls. For hypoxic training, the horses wore a semi-open flow mask that delivered 15.1 ± 0.2% inspired O2 during exercise. The running speed on the treadmill was set to elicit exhaustion between 2–3 min after warm-up (1.7 m/sec for 2 min, 4.0 m/sec for 2 min, and 7.0 m/sec for 2 min). The horses had 5 hypoxic exercise training episodes during the span of 3 weeks.

Cardiorespiratory valuables on a treadmill

Exercise evaluations were performed to measure O2 transport variables and the running distance before exhaustion for each horse in normoxia at the end of normoxic training (before hypoxic training) and at the end of hypoxic training (after hypoxic training). The running distance was calculated as the sum of the running speed × 2 min at each running step. Before leading a horse onto the treadmill, a 14-ga Teflon® catheter was placed in the left jugular vein following injection of a local anesthetic agent. The exercise protocol when breathing normoxic gas consisted of a warm-up (1.7 m/sec for 2 min and 3.5 m/sec for 3 min) followed by 2-min exercise intervals at 1.7, 4.0, 7.0, 10.0, 12.0, 13.0, and 14.0 m/sec until the horse could not maintain its position at the front of the treadmill with humane encouragement, all with the treadmill inclined to a 6% grade and with the horse breathing normoxic gas (Fig. 1). Horses wore an open-flow mask for measurement of V̇O2 and CO2 production (V̇CO2). Heart rate was measured with a heart rate monitor (S810, Polar, Kempele, Finland), and venous blood was drawn from the jugular catheter to measure the plasma lactate concentration ([LAC]) and packed cell volume (PCV). Blood samples were centrifuged (KH120A, Kubota, Tokyo, Japan) for 5-min (12,000 × g) to measure PCV, as well as for 5 min (1,800 × g) to separate plasma for measurement of [LAC] in a lactate analyzer (Biosen C-Line Glucose & Lactate Analyser, EKF-diagnostic GmbH, Barleben, Germany).

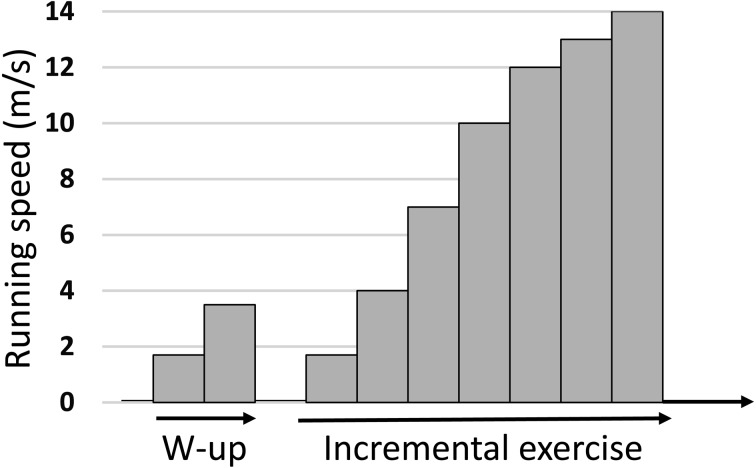

Fig. 1.

The exercise protocol during treadmill exercise when cardiorespiratory valuables were measured. After warming up (W-up), horses underwent an incremental exercise protocol consisting of an increase in treadmill speed every 2 min until they were exhausted.

Oxygen consumption

Horses wore a 25-cm diameter open-flow mask on the treadmill, with a rheostat-controlled 3.8-kW blower drawing air through it at bias-flow rates of 6,000–8,000 l (ATP)/min. Air flowed through 20-cm-diameter wire-reinforced flexible tubing affixed to the mask and across a 25-cm-diameter pneumotachograph (LF-150B, G. N. Sensor, Chiba, Japan) connected to a differential pressure transducer (TF-105, G. N. Sensor); this was used to ensure that bias flows during measurements were identical to those during calibrations. Oxygen consumption and V̇CO2 were measured with standard mass-balance techniques [1, 8] using an O2 and CO2 analyzer (METS-900, VISE Medical, Chiba, Japan), 2-m-long Nafion® drying tube with countercurrent dry gas flow (Drierite (CaSO4)) to remove H2O from sample gas, and electronic mass flowmeters (Model DPM3, Kofloc, Tokyo, Japan) for measuring N2 and CO2 calibration flows using the N2-dilution/CO2-addition technique [5]. Gas analyzer and flowmeter outputs were recorded with A/D hardware (DI-720-USB, DATAQ Instruments, Akron, OH, U.S.A.) and software (Windaq Pro+, DATAQ Instruments, Akron) on personal computers.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons were made using analysis of variance with pre- or post-hypoxic training as the treatment. A P-value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Before hypoxic training commenced, the V̇O2max values during the 3 consecutive weeks of supramaximal normoxic training, whch was perfoemed twice per week were 178 ± 9.1, 180 ± 10.0, and 178 ± 10.1 ml O2 (STPD)/(kg × min), respectively. The total running distance for the final normoxic exercise run, at which time the final measurement of V̇O2max was obtained before hypoxic training, was 5,174 ± 759 m.

The total running distance during hypoxic exercise was 2,987 ± 567 m. The running speed that elicited exhaustion in hypoxia between 2–3 min was 12.1 ± 0.45 m/sec. After hypoxic training, the average body weight of the horses was 482 ± 30 kg.

Table 1 shows a summary for the results of the cardiorespiratory valuables. The mass-specific V̇O2max increased from 178 ± 10.1 ml O2 (STPD)/(kg × min) before hypoxic training to 194 ± 12.3 ml O2 (STPD)/(kg × min) after hypoxic training; absolute V̇O2max also increased after hypoxic training. Total running distance after hypoxic training increased 12% compared with that before hypoxic training, but there was no difference between them (P=0.29). There were no differences between pre- and post-hypoxic training for [LAC] or PCV (Table 1).

Table 1. Cardiorespiratory valuables before and after hypoxic training.

| Variable | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| Body mass (kg) | 483 ± 26 | 482 ± 30 |

| Total running distance (m) | 5,174 ± 759 | 5,808 ± 981 |

| Total running time (min) | 11.33 ± 0.95 | 12.07 ± 1.22 |

| Heart rate (beat/min) | 214 ± 5 | 217 ± 7 |

| V̇O2/Mb (ml O2 (STPD)/(min × kg)) | 178 ± 10 | 194 ± 12* |

| V̇CO2/Mb (ml CO2 (STPD)/(min × kg)) | 202 ± 12 | 214 ± 20 |

| Respiratory exchange ratio | 1.14 ± 0.02 | 1.10 ± 0.04* |

| Absolute V̇O2 (l O2 (STPD)/min) | 86.6 ± 6.2 | 93.6 ± 6.6* |

| Absolute V̇CO2 (l CO2 (STPD)/min) | 97.8 ± 7.3 | 102.7 ± 8.0 |

| End-run [LAC] (mmol/l) | 23.1 ± 3.3 | 23.2 ± 6.8 |

| PCV (%) | 65.0 ± 3.3 | 66.1 ± 3.2 |

Cardiorespiratory valuables were recorded during a run at a speed eliciting V̇O2max. Mb: body mass. Mean values (± SD) are shown. *Significant difference (P≤0.05) compared with before hypoxic training.

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the effects of hypoxic training on V̇O2max using well-trained horses in which V̇O2max had not increased over 3 consecutive weeks of twice a week supramaximal treadmill training in normoxia. Three weeks of training while inspiring 15% O2 twice a week improved not only the horses’ mass-specific V̇O2max, but also their absolute V̇O2max. Total running distance after 3 weeks of hypoxic training had increased 12% compared with that at the onset of hypoxic training, although this difference in total running distance between before and after hypoxic training was not significant. This may have been due to the high variance in the distance-run data resulting in low statistical power to detect a significant difference. These results suggest that hypoxic training is an effective method for increasing aerobic capacities of horses compared with only using normoxic training.

It has been reported that Thoroughbred horses experience severe hypoxemia when exercising at V̇O2max [3, 14, 15, 22]. Severe hypoxemia may contribute to elevation of aerobic capacity in Thoroughbred horses, as it suggests that horses are maximally utilizing all components of their O2 transport system, even to the point of becoming hypoxemic and experiencing reduced O2 saturation of arterial blood. Therefore, we wondered if hypoxic training might be effective for increasing V̇O2max and enhancing the performance of well-trained Thoroughbred horses. We found in this study that hypoxic training is effective in increasing V̇O2max in highly trained Thoroughbred horses compared with their normoxic V̇O2max. Hypoxic training may generate more severe hypoxemia than does normoxic training, and we speculate that the existence of more severe hypoxemia may contribute to increasing V̇O2max; it will be useful to measure the arterial blood O2 concentration in hypoxia in the future.

We have previously found that hypoxic training improves V̇O2max and that it increases the running distance before exhaustion in untrained horses [12]. However, the running speeds on the treadmill were the same for both normoxic and hypoxic training. In that study, the relative intensity (percentage of V̇O2max) of hypoxic exercise was higher than that of normoxic exercise [12]. Therefore, it is possible that the differences in V̇O2max and running distance resulted from differences in the relative intensity of the exercise in that study. In this study, it was difficult to directly compare running speed and running distance between normoxic (i.e., before hypoxic) training and hypoxic training because the exercise protocols were not identical. However, the absolute exercise intensity in normoxia was greater than in hypoxia because the total running distance, running speed, and run time in normoxia were greater than in hypoxia. However, both normoxic and hypoxic training were at the same relative intensity in terms of the fact that all horses ran to exhaustion, although the run time in normoxia was longer than that in hypoxia. Nevertheless, hypoxic training appears to be an effective method to improving V̇O2max in horses, perhaps due to a stimulus resulting from breathing hypoxic gas, given that V̇O2max had not increased in these horses over 3 consecutive weeks of supramaximal treadmill training in normoxia. It appears that hypoxic training may enhance the aerobic capacities of horses compared with normoxic training.

It has been reported that altitude training in humans increases the hemoglobin concentration, resulting in increased aerobic capacity [6, 19,20,21]. It has also been reported that altitude training in human endurance athletes may explain more than half of the increase in V̇O2max that occurs due to increased hemoglobin mass [20]. In contrast, there was no significant difference in PCV between before and after hypoxic training in this study; it is possible that non-hematological changes may play a role in increasing V̇O2max in Thoroughbreds. It is known that PCV in Thoroughbreds increases when running because of mobilization of erythrocytes stored in the spleen [17]. Therefore, it is not clear whether increased PCV contributes to increased equine performance or not; further study of this question is needed.

Mizuno et al. reported that increases in O2 deficit (29%) and short-term running performance (17%) were observed after 2 weeks of altitude (2,700 m) training in humans, although V̇O2max remained at the pre-altitude training value [11]. Some reports suggest that high-intensity intermittent training in hypoxia may increase anaerobic performance [7, 11]; some studies have found that performance, e.g., run time to exhaustion, increased without increased V̇O2max [9, 11]. End-run lactate concentrations were nearly the same values before and after hypoxic training in this study. In Thoroughbreds, the plasma lactate accumulation rate is related to net anaerobic capacity [13, 16]. Therefore, it is possible that hypoxic training may not increase net anaerobic power in Thoroughbreds, as end-run [LAC] was nearly the same at exhaustion in this study when breathing either gas.

It has been reported that altitude training may decrease body weight [2]. In this study, the horses maintained body weight during hypoxic training, likely because the horses used were highly trained in normoxia a priori. In terms of energy expenditure, horses running while breathing hypoxic gas consumed less O2 because their running speeds and running distances were less than those in normoxia. Because the horses were not living in chronic hypoxia but instead only ran acutely while breathing hypoxic gas during experiments, this may have contributed to the horses’ maintaining their body weights during the course of the experiments.

In summary, it appears that training while breathing hypoxic gas may have the potential to enhance the peak normoxic performance of Thoroughbred horses. Although the specific mechanisms responsible for eliciting this difference are not yet known, the effect of the hypoxic stimulus, even during this relatively brief duration of exposure, is striking.

References

- 1.Birks E.K., Jones J.H., Berry J.D. 1991. Plasma lactate kinetics in exercising horses. pp. 179–187. In: Equine Exercise Physiology 3. (Persson, S.G.B., Lindholm, A. and Jeffcott, L.B., eds.), ICEEP Publications, Davis. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyer S.J., Blume F.D. 1984. Weight loss and changes in body composition at high altitude. J. Appl. Physiol. 57: 1580–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erickson B.K., Seaman J., Kubo K., Hiraga A., Kai M., Yamaya Y., Wagner P.D. 1995. Hypoxic helium breathing does not reduce alveolar-arterial PO2 difference in the horse. Respir. Physiol. 100: 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faiss R., Léger B., Vesin J.M., Fournier P.E., Eggel Y., Dériaz O., Millet G.P. 2013. Significant molecular and systemic adaptations after repeated sprint training in hypoxia. PLoS ONE 8: e56522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fedak M.A., Rome L., Seeherman H.J. 1981. One-step N2-dilution technique for calibrating open-circuit VO2 measuring systems. J. Appl. Physiol. 51: 772–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gore C.J., Clark S.A., Saunders P.U. 2007. Nonhematological mechanisms of improved sea-level performance after hypoxic exposure. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 39: 1600–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamlin M.J., Marshall H.C., Hellemans J., Ainslie P.N., Anglem N. 2010. Effect of intermittent hypoxic training on 20 km time trial and 30 s anaerobic performance. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 20: 651–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones J.H., Longworth K.E., Lindholm A., Conley K.E., Karas R.H., Kayar S.R., Taylor C.R. 1989. Oxygen transport during exercise in large mammals. I. Adaptive variation in oxygen demand. J. Appl. Physiol. 67: 862–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasai N., Mizuno S., Ishimoto S., Sakamoto E., Maruta M., Goto K. 2015. Effect of training in hypoxia on repeated sprint performance in female athletes. Springerplus 4: 310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kon M., Nakagaki K., Ebi Y., Nishiyama T., Russell A.P. 2015. Hormonal and metabolic responses to repeated cycling sprints under different hypoxic conditions. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 25: 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mizuno M., Juel C., Bro-Rasmussen T., Mygind E., Schibye B., Rasmussen B., Saltin B. 1990. Limb skeletal muscle adaptation in athletes after training at altitude. J. Appl. Physiol. 68: 496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagahisa H., Mukai K., Ohmura H., Takahashi T., Miyata H. 2016. Effect of high-intensity training in normobaric hypoxia on Thoroughbred skeletal muscle. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016: 1535367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohmura H., Hiraga A., Jones J.H. 2006. Method for quantifying net anaerobic power in exercising horses. Equine Vet. J. Suppl. 2006: 370–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohmura H., Hiraga A., Jones J.H. 2013. Exercise-induced hypoxemia and anaerobic capacity in Thoroughbred horses. J. Phys. Fit. Sports Med 2: 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohmura H., Matsui A., Hada T., Jones J.H. 2013. Physiological responses of young thoroughbred horses to intermittent high-intensity treadmill training. Acta Vet. Scand. 55: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohmura H., Mukai K., Takahashi T., Matsui A., Hiraga A., Jones J.H. 2010. Comparison of net anaerobic energy utilisation estimated by plasma lactate accumulation rate and accumulated oxygen deficit in Thoroughbred horses. Equine Vet. J. Suppl. 42: 62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Persson S. 1967. On blood volume and working capacity in horses. Studies of methodology and physiological and pathological variations. Acta Vet. Scand. 19: 9–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richardson A.J., Relf R.L., Saunders A., Gibson O.R. 2016. Similar inflammatory responses following sprint interval training performed in hypoxia and normoxia. Front. Physiol. 7: 332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodríguez F.A., Ventura J.L., Casas M., Casas H., Pagés T., Rama R., Ricart A., Palacios L., Viscor G. 2000. Erythropoietin acute reaction and haematological adaptations to short, intermittent hypobaric hypoxia. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 82: 170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saunders P.U., Garvican-Lewis L.A., Schmidt W.F., Gore C.J. 2013. Relationship between changes in haemoglobin mass and maximal oxygen uptake after hypoxic exposure. Br. J. Sports Med. 47(Suppl 1): i26–i30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt W., Heinicke K., Rojas J., Manuel Gomez J., Serrato M., Mora M., Wolfarth B., Schmid A., Keul J. 2002. Blood volume and hemoglobin mass in endurance athletes from moderate altitude. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 34: 1934–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagner P.D., Erickson B.K., Seaman J., Kubo K., Hiraga A., Kai M., Yamaya Y. 1996. Effects of altered FIO2 on maximum VO2 in the horse. Respir. Physiol. 105: 123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]