Abstract

Importance

Oxidative stress is an established dementia pathway, but it is unknown if the use of antioxidant supplements can prevent dementia.

Objective

To determine if antioxidant supplements (vitamin E or selenium) used alone or in combination can prevent dementia in asymptomatic older men.

Design

PREADVISE, designed to answer this question, began as a double-blind, randomized controlled trial in 2002 which transformed into a cohort study from 2009–2015.

Setting

PREADVISE was ancillary to SELECT, a randomized controlled trial of the same anti-oxidant supplements for preventing prostate cancer. SELECT closed in 2009 due to a futility analysis.

Participants

PREADVISE recruited 7,540 men, of whom 3,786 continued into the cohort study. Participants were at least 60 years old at study entry and were enrolled at one of 130 SELECT sites.

Intervention

Participants were randomized to vitamin E, selenium, vitamin E + selenium, or placebo. While taking study supplements, PREADVISE men visited their SELECT site and were evaluated for dementia using a two-stage screen. During the cohort study, men were contacted by telephone and assessed using an enhanced two-stage cognitive screen. In both phases, men were encouraged to visit their doctor if the screen indicated possible cognitive impairment.

Main Outcome

Dementia case ascertainment relied on a consensus review of the cognitive screens and medical records for those suspected cases that visited their doctor for an evaluation, or by review of all supplemental information provided by SELECT, including a functional assessment screen.

Results

Under a modified intent-to-treat analysis, dementia incidence (4.43%) was not different among the four study arms. A Cox model, which adjusted incidence for participant demographics and baseline self-reported co-morbidities, yielded hazard ratios of 0.88 (95% CI: 0.64–1.20) for vitamin E, 1.00 (0.75–1.35) for the combination, and 0.83 (0.60–1.13) for selenium compared to placebo.

Conclusions and Relevance

Neither supplement prevented dementia. This is the first study to investigate the long term effect of anti-oxidant supplement use on dementia incidence among asymptomatic men.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00040378.

Introduction

In the United States (US) an estimated 5 million elderly have Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and AD cases are expected to increase substantially by 2050.1 A recent review of clinical trials from 1984–2014 shows a focus on enrolling mild to moderate dementia cases in many trials with no real progress on identifying disease modifying treatments2. As a result, there has been a shift in focus to clinical trials emphasizing the prevention of cognitive decline, especially through secondary prevention trials targeting high risk groups3,4 and large trials that promote lifestyle changes to address modifiable risk factors for AD5,6. The usual primary endpoints of these trials are cognitive decline or composites of biomarkers and cognitive measures7. The gold standard of prevention is disease incidence, but few current trials have this as their primary endpoint because of the time required to observe reductions in disease incidence.

Multiple mechanisms associated with disease onset and progression have been described,8 and one key mechanism implicated in AD is oxidative stress,9 which may be modifiable through diet and/or antioxidant supplements10. Antioxidant use as a potential treatment for cognitive impairment or dementia has been of interest for many years. Vitamin E has had mixed results in treatment trials: in moderately demented patients treated for two years, its use slowed disease progression,11 but more recently, when used in an antioxidant cocktail, its use failed to improve cognition in AD patients with mild to moderate dementia12. It also failed as a preventive agent for dementia progression in subjects with mild cognitive impairment (MCI),13 although early in the trial its use did somewhat improve cognition. A review of controlled trials and case-control studies on the use of selenium in arresting the progression of AD also yields mixed results14. Observational studies correlate cognitive decline with decreased plasma selenium over time15,16. However, nothing is known about long-term use of these supplements as preventative agents in asymptomatic individuals. The purpose of this manuscript is to address this gap in the literature.

Specifically, this manuscript reports the main results of the Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease with Vitamin E and Selenium (PREADVISE) primary prevention trial. PREADVISE, the largest primary prevention trial in AD to date, began in 2002 as an ancillary trial within the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT), a double-blind, randomized controlled prostate cancer prevention trial17. When SELECT ended prematurely in 2009 due to a futility analysis, PREADVISE continued as a cohort study for a subset of its enrollees18. Extended follow-up over a seven-year period (blinded) allowed for case ascertainment, yielding a comparison of the study arms for effectiveness in preventing dementia. We present the results of this large primary prevention study of antioxidant supplements as a method to modify oxidative stress, one mechanism in the evolution of AD9.

Methods

Design

Study design19, participant recruitment20, and the conversion of the trial into a cohort study18 are described in earlier publications. Briefly, the parent study, SELECT, was designed as a double-blind, four-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) and initiated enrollment in 200117. SELECT’s primary aim was to determine the effectiveness of the antioxidant supplements vitamin E (400 IU/day) and selenium (200 μg/day) alone or in combination in preventing prostate cancer. PREADVISE recruited a subsample of SELECT participants age 62 and over (age 60 if black) at 130 participating clinical sites in the US, Canada, and Puerto Rico. PREADVISE enrolled 7,540 non-demented SELECT men between 2002 and 2008 (Appendix, CONSORT diagram). The RCT was powered to detect a hazard rate of 0.60 with 80% power assuming a targeted enrollment of 10,400 men; this was then lowered to a detectable hazard rate 0.5 once the actual enrollment finished at 7,540 men.

Study eligibility required SELECT enrollment at a participating site and absence of: dementia, active neurologic and/or neuropsychiatric conditions that affect cognition, as well as history of serious head injury (>30-minute loss of consciousness within the last five years prior to enrollment) and substance abuse. The RCT was scheduled to continue supplements until 2012 but in September 2008, the SELECT Data and Safety Monitoring Committee recommended that supplements be discontinued due to lack of efficacy on prostate cancer incidence. Study sites closed over the next two years, during which time both PREADVISE and SELECT transitioned into cohort studies18,21. RCT participants were asked to continue in the cohort study, and 4,271 of the original 7,540 PREADVISE men consented to continue annual memory screenings, which were then conducted by telephone. All study activities were approved by Institutional Review Boards at the University of Kentucky and at each SELECT site. All participants provided written informed consent.

Screening

The Memory Impairment Screen (MIS)22 was used as the primary screening instrument in both the RCT and cohort study. Participants who scored below cutoffs for intact cognition received a secondary screening instrument. The modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-m)23 was used during the cohort study, replacing the expanded Consortium to Establish a Registry in Alzheimer’s Disease (CERADe) neuropsychological battery24 used during the RCT. Annual screenings were completed in May 2014, and case ascertainment follow-up continued until fall 2015. All PREADVISE participants who completed at least one follow-up visit were included in the current analyses (intent-to-treat analysis, ITT), whether they participated in just the RCT or both the RCT and cohort studies.

Case Ascertainment

Dementia incidence, the primary endpoint, was determined by one of two methods. First, if a man failed both the first tier of the screen (MIS ≤5 out of 8) and the second tier (T Score ≤ 35 on the CERAD battery, total score ≤ 35 on the TICS-m), then he was encouraged to obtain a memory work-up from his local clinician and share the medical records with PREADVISE. Medical records were reviewed by a team of 2–3 expert neurologists and 2–3 expert neuropsychologists to determine a consensus diagnosis. Participants who did not obtain the work-up were assessed by additional longitudinal measures collected during the study. These included the AD8 Dementia Screening Interview26, self-reported medical history, self-reported medication use, and cognitive scores including the MIS, CERAD T Score, NYU Paragraph Delayed Recall27, and TICS-m. An AD8 ≥1 (at any time during follow-up) plus a self-reported dementia diagnosis, use of a memory enhancing prescription drug (i.e., donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, memantine), or cognitive score ≥1.5 standard deviations below expected performance yielded a dementia diagnosis. The diagnosis date was assigned to the earliest event.

Statistical Methods

Groups were compared using chi-square statistics for categorical variables and two-sample t-tests or analysis of variance for interval level variables. Cox proportional hazards models were used perform a modified intent-to-treat (mITT) analysis to compare hazard rates among the study arms. Hazard ratios were adjusted for the following covariates: baseline age, black race, APOE ε4 carrier status (present or absent), college education, baseline MIS score, and the presence/absence of the following self-reported co-morbidities at PREADVISE baseline: coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), congestive heart failure (CHF), diabetes, hypertension, stroke, sleep apnea, and memory change or problem. In this analysis, survival time is the time from PREADVISE baseline to ascertainment of a case (event) or last cognitive assessment (right censored). All dropouts due to death, personal withdrawals from the study, and administrative withdrawals (e.g., SELECT sites not re-consenting men for the cohort study) were right censored. The proportional hazards assumption required by the Cox model was checked using martingale residuals and Schoenfeld residuals. The latter analysis indicated that proportionality was met for the indicators of the treatment arms and all covariates except for the indicators of baseline memory problems and baseline MIS score less than 7 or 8. A stratified analysis using the combination of these latter two variables yielded the same results for the effect of the treatment arms. Therefore, the original Cox model is reported here. Missing APOE ε4 carrier status values (4.8% of the subjects) were imputed; a re-analysis limited to known APOE ε4 yielded virtually the same results as those reported here.

Three additional analyses were conducted. First, the observations were weighted by treatment compliance. This weight equaled the length of time the man could take the supplements (time between enrollment and the date the supplements were stopped) multiplied by the proportion of visits at which the man was compliant with assigned supplement one (vitamin E or placebo) or compliant with supplement two (selenium or placebo), whichever was greater. Compliance information was based on returned pill counts. For example, suppose a randomly selected study participant had three years on treatment, and he was found to be 50% compliant with assigned treatment. The weight assigned to that man’s record was 1.5 (3 years × 50% compliance, normed to make the sum of all weights equal the sample size for this analysis given the 7,289 men with compliance information). Second, the Cox models were re-fitted using only medical records-based dementia cases as the outcome (cases identified without medical records were right censored).

Results

Table 1 shows that participants evaluated with at least one memory screen in the cohort study (n=3,786) were similar to the complete PREADVISE enrollment, except possibly for less education at the college level or higher (52.2% versus 60%), fewer black participants (8.4% versus 10.0%), and fewer Hispanic participants (2.5% versus 6.9%). Table 2 lists participant characteristics at the time of PREADVISE enrollment by study arm. Based on the means and percentages, despite randomization occurring at SELECT baseline rather than PREADVISE enrollment, there were no perceivable differences between study arms in terms of medical history, APOE ε4 genotype, or initial MIS.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of men at PREADViSE entry and the subset who continued into the cohort study

| Baseline measure | PREADViSE Baseline (n=7,540) | Cohort Study (n=3,786) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) years | 67.5 (5.3) | 67.3 (5.2) |

| MIS, mean (SD) | 7.6 (0.7) | 7.6 (0.7) |

| APOE 4 carrier (%) | 1,993 (25.5) | 954 (25.2) |

| Family History (%) | 1,606 (21.3) | 859 (22.7) |

| ≥ College Education (%) | 3,936 (52.2) | 2,272 (60.0) |

| Black Race (%) | 754 (10.0) | 318 (8.4) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity (%) | 505 (6.7) | 95 (2.5) |

| Memory Change (%) | 1,779 (23.6) | 852 (22.5) |

| Memory Problem (%) | 121 (1.6) | 49 (1.3) |

| Hypertension (%) | 3,024 (40.1) | 1,412 (37.3) |

| Diabetes (%) | 860 (11.4) | 35 (9.3) |

| Sleep Apnea (%) | 550 (7.3) | 295 (7.8) |

| CABG (%) | 317 (4.2) | 136 (3.6) |

| Stroke (%) | 45 (0.6) | 11 (0.3) |

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of men in the mITT analysis by study arm (n=7,338*)

| Baseline | Placebo | Vitamin E | Selenium | Combination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) years | 67.3 (5.2) | 67.5 (5.2) | 67.6 (5.3) | 67.6 (5.3) |

| MIS, mean (SD) | 7.6 (0.7) | 7.6 (0.7) | 7.6 (0.7) | 7.6 (0.7) |

| APOE 4 carrier (%) | 459 (25.1) | 484 (26.9) | 493 (26.2) | 439 (24.0) |

| Family History (%) | 384 (21.0) | 417 (23.2) | 376 (20.0) | 393 (21.5) |

| ≥ College Ed (%) | 975 (53.3) | 946 (52.6) | .976 (51.9) | 962 (52.6) |

| Black Race (%) | 168 (9.2) | 175 (9.7) | 182 (9.7) | 172 (9.4) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity(%) | 115 (6.3) | 124 (6.9) | 115 (6.1) | 130 (7.1) |

| Memory Change (%) | 412 (22.5) | 437 (24.3) | 450 (23.9) | 439 (24.0) |

| Memory Problem (%) | 27 (1.5) | 27 (1.5) | 30 (1.6) | 29 (1.6) |

| Hypertension (%) | 756 (41.3) | 698 (38.8) | 749 (39.8) | 718 (39.3) |

| Diabetes (%) | 207 (11.3) | 210 (11.7) | 214 (11.4) | 196 (10.7) |

| Sleep Apnea (%) | 137 (7.5) | 146 (8.1) | 126 (6.7) | 124 (6.8) |

| CABG (%) | 82 (4.5) | 74 (4.1) | 75 (4.0) | 73 (4.0) |

| Stroke (%) | 7 (0.4) | 5 (0.3) | 13 (0.7) | 13 (0.7) |

excludes 201 participants with no follow-up

Incident dementia cases were defined as above. There were 325/7,540 incident dementia cases in the study (4.31%) and, of these, 121/325 (37.2%) provided medical records (Table 3). Unadjusted cumulative incidence varied among the study arms: 3.95% in the vitamin E arm, 4.15% in the selenium arm, 4.62% in the placebo arm, and 4.96% in the combination arm (Table 3).

Table 3.

Incident cases of dementia by study arm

| Arm | Demented (%) | Not Demented (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 85 (4.62) | 1,745 (95.38) | 1,830 (100) |

| Vitamin E | 71 (3.95) | 1,728 (96.05) | 1,799 (100) |

| Selenium | 78 (4.15) | 1,803 (95.95) | 1,881 (100) |

| Combination | 91 (4.98) | 1,737 (95.02) | 1,828 (100) |

| Total | 325 (4.43) | 7,013 (95.57) | 7,338 (100) |

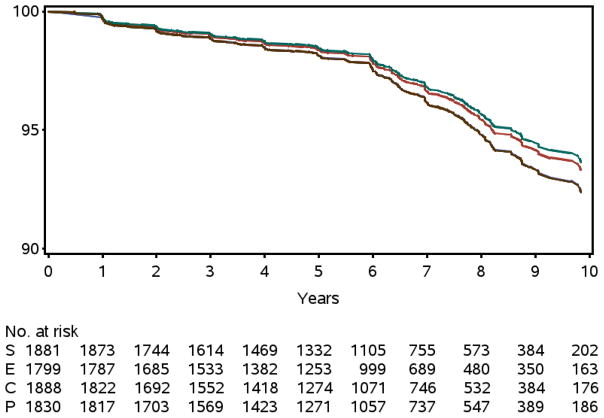

To compare the hazard rates for dementia among the four study arms, mITT analysis based on a Cox proportional hazards model was fitted to the data. The mITT analysis excluded 201 participants who had only a baseline visit. Hence, the Cox model included 7,338 men with at least one follow-up visit. None of the active study arms had a significantly lower adjusted hazard rate for incident dementia when compared to the placebo arm; the selenium arm had a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.83 vs. placebo (95% CI: 0.61–1.13), while the vitamin E arm had HR=0.88 (95% CI: 0.64–1.20) (Table 4). The combined supplements arm was indistinguishable from the placebo arm had HR=1.00 (95% CI: 0.74–1.35) (Figure 1).

Table 4.

Adjusted hazard ratios (HR*) by study arm for both the mITT analysis and the weighted analysis

| ITT | Weighted** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value |

| Vitamin E | 0.88 (0.64–1.20) | 0.41 | 0.84 (0.61–1.15) | 0.27 |

| Selenium | 0.83 (0.61–1.13) | 0.23 | 0.80 (0.59–1.09) | 0.16 |

| Combined | 1.00 (0.74–1.35) | 0.98 | 0.99 (0.74–1.32) | 0.93 |

All HR estimates are vs. Placebo;

weighted analysis is missing 50 participants

Figure 1. Probability Dementia Free.

The probability of a male being dementia free by year of follow-up and study arm. Top curve is selenium (S), middle curve is vitamin E (E), and bottom two curves are placebo (P) and the combined supplements (C). Plot obtained from the Cox model; there were no significant differences (P = 0.80).

Since this was a truncated RCT (due to the futility analysis for the SELECT trial as described above), the Cox model was re-fitted by weighting each man’s survival time to dementia by the length of time that man was exposed (time on supplement) multiplied by the estimated proportion of this time that the man was compliant with the assigned treatment (i.e., compliance). The weighted analysis showed results similar to the unweighted mITT analysis (Table 4).

Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted. First, the analysis was restricted to the 3,786 participants who volunteered for the cohort study and were screened by telephone at least once; here, the number of incident dementia cases was 228. The reported effects were HR=0.92 (95% CI: 0.63–1.34) for selenium and HR=0.97 (95%CI: 0.65–1.43) for E and HR=1.18 (95% CI: 0.82–1.68) for both. Second, the analysis used all 7,338 subjects with at least one annual follow-up screen, but only classified a participant as having dementia if confirmed by medical records. This reduced the number of events to 121 as stated above yielding HR = 0.70 (95%CI: 0.41–1.19) for selenium, HR=0.80 (95%CI: 0.59–1.62) for vitamin E and HR=0.97 (95%CI: 0.60–1.58) for both.

Discussion

PREADVISE was a double-blind RCT conducted as an ancillary study to a cancer prevention trial (SELECT), both of which evolved into observational cohort studies. This trial investigated whether the supplements vitamin E and selenium used alone or in combination would prevent new AD or dementia cases. The results showed that neither vitamin E or selenium (with 5.4± 1.2 years of supplement use) had a significant preventive effect on incidence. One possible explanation for the negative findings is that the trial met only 75% of its planned accrual; however, the results also show that the effect sizes observed for either supplement are likely much lower than the projected HR of 0.6019. Nevertheless, this is the first, large-scale primary prevention trial to investigate the effect of antioxidant supplements on reducing dementia incidence.

PREADVISE is a member of the first generation of AD prevention trials28–31, all of which failed in their primary goal. One common reason for the failure of those trials was the low incidence of AD and dementia observed during follow-up. This was attributed partially to selection bias, since participants had higher levels of education than the general population and perhaps more cognitive reserve. Dementia incidence among PREADVISE participants was very low for several additional reasons. Case ascertainment could not use modern diagnostic procedures since suspected cases did not, as a rule, visit dementia specialists for diagnosis. Instead, ascertainment relied on a consensus review of medical records derived from a variety of care providers. Case ascertainment was also affected by continual staff turnover at study sites in the RCT component of the study, which was associated with a low cognitive screen failure rate (less than 1%). The failure rate increased substantially once centralized follow-up began18.

The rationale for this trial was supported by results from the basic sciences, as well as observational and prospective studies in humans suggesting that the use of antioxidants improved cognition and reduced dementia incidence. The studies preceding the trial focused more on the benefits of vitamin E, since at that time it was being evaluated in a number of therapeutic trials, including a trial that studied its effect on the progression of MCI to dementia13. As in the MCI trial, vitamin E had no effect on dementia incidence in the asymptomatic cohort in PREADViSE.

A recent review of studies on selenium argues that selenium is vital for central nervous system function and that brain selenium levels are maintained at the expense of other tissues32. A study of 2,000 rural Chinese over age 64 years showed that participants in the lowest quintile of nail selenium levels had significantly lower scores on all instruments in the CERAD battery except for animal fluency16. It is well known that high levels of selenium are toxic, inducing a severe selenosis by pro-oxidant action and glial activation, leading to neuronal death33.

For PREADVISE, dose decisions were made by a committee in the parent SELECT study34. The absence of biomarkers for target engagement of the supplements makes it difficult to translate basic science findings into prevention trials in a rigorous manner.

Data monitoring in SELECT showed that selenium appeared to elevate levels of Type II diabetes, although this elevated rate subsequently decreased with additional follow-up and that vitamin E appeared to increase prostate cancer incidence35. The supplements had no effect on mortality, other cancers, cardiovascular events, nausea, fatigue, or nail changes. Selenium was associated with a significant increase in alopecia and grade 1–2 dermatitis17 (Tables 4–5).

The transitioning process cost the study about half of its participants for long-term follow-up; this was unavoidable since the study had to rely on SELECT sites to enroll the participants for the cohort study. Fortunately, Table 1 shows that the major cost was sample size (reduction in person-years of follow-up) since no new large selection biases were introduced. Aside from the transitioning to a cohort study from an RCT, PREADVISE had other limitations. Publicity about the negative effect of supplements may have affected the conduct of both the RCT and cohort study. SELECT reports on the potentially harmful effects of vitamin E (increased prostate cancer) and selenium (potentially increased diabetes), coupled with outside negative reports on vitamin E (i.e., increased mortality36) created issues to be addressed37. Many individuals who failed the screening instruments refused to see clinicians for further testing; recent research suggests that this could be due to the stigma attached to such an event or living alone38. This complicated case ascertainment. AD diagnoses that rely on the choice of cut points on neuropsychological tests have been shown to fail to identify individuals in the initial symptomatic stages of the disease39. Hence, our methods for case ascertainment could have missed cases that would have been identified by more rigorous in-clinic examinations. Future trials may benefit from electronic medical records. The reluctance to visit doctors prompted the introduction of the AD8 during the follow-up phase of the study, which could have induced bias due to the inability of participants or informants to distinguish anosognosia from dementia. This is a likely a small bias since examining the subjects with medical records showed a high level of agreement with the AD8 as also evidenced in another study40. The reliability of telephone assessments versus in-clinic assessments used in the two phases of the study was less of an issue due to high intraclass correlations, which were in the range 0.92–0.9841. In addition, the TICS-m has been shown to be a reliable discriminator between cognitively intact individuals and those with amnestic MCI42.

Conclusion

The supplemental use of vitamin E and selenium did not forestall dementia and are not recommended as preventative agents. This conclusion is tempered by the underpowered study, inclusion of only men, a sort supplement exposure time, dosage considerations, and methodologic limitations in relying on real world reporting of incident cases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Additional support for the current study comes from NIA R01 AG038651 and NIA P30 AG028383. SELECT was supported by NCI CA37429 and UM1 CA182883. NCI was involved in the design of SELECT. Otherwise, the sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the current study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the preparation of the manuscript; or in the review or approval of the manuscript.

We gratefully acknowledge all PREADVISE volunteers for their many years of participation, the support staff of PREADViSE at the University of Kentucky, and the SWOG Statistical Center at Cancer Research and Biostatistics for assistance with study procedures and data management. We also acknowledge Dr. Gregory Jicha, M.D., and Dr. John Ranseen, Ph.D., at the University of Kentucky and Dr. Gregory Cooper, M.D. at Baptist Health Medical Group Neurology for reviewing medical records on suspected cases; Dr. Steven Estus, Ph.D., and Dr. Donna Wilcock, Ph.D., at the University of Kentucky for APOE genotyping; and Dr. Marta Mendiondo, Ph.D., (retired) for expertise in data management. We thank Dr. Herman Buschke, M.D., at Albert Einstein College of Medicine for recommending the MIS as the first stage screening instrument. The project also acknowledges the late Dr. William Markesbery, M.D., the original P.I. of PREADVISE.

Footnotes

Data Access: RJK and ELA had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflict of interest: All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards: The study protocol was approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board in addition to Institutional Review Boards at each study site. All participants provided written informed consent.

References

- 1.Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider LS, Mangialasche F, Andreasen N, et al. Clinical trials and late-stage drug development for Alzheimer’s disease: an appraisal from 1984 to 2014. J Int Med. 2014;275(3):251–283. doi: 10.1111/joim.12191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Brayne C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:788–794. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70136-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon A, Mangialasche F, Richard E, et al. Advances in the prevention of Alzheimer’ disease and dementia. J Intern Med. 2014;275:229–250. doi: 10.1111/joim.12178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kivipelto M, Solomon A, Ahtiluoto S, et al. The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER): study design and progress. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(6):657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A, et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9984):2255–2263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kryscio RJ. Secondary prevention trials in Alzheimer disease: the challenge of identifying a meaningful end point. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(8):847–949. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogen-Shtern N, Ben David T, Lederkremer GZ. Protein aggregation and ER stress. Brain Res. doi: 10.1016/jbrainres2016.03.044. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rinaldi P, Polidori MC, Metastasio A, Mariani E, Mattioli P, Cherubini A, Catani M, Cecchetti R, Senin U, Mecocci P. Plasma antioxidants are similarly depleted in mild cognitive impairment and in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(7):915–919. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(03)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vina J, Lloret A, Orti R, Alonso D. Molecular bases of the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease with antioxidants; prevention of oxidative stress. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2004;25(10):117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas RG, et al. A controlled trial of selegiline, alpha-tocopherol, or both as treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1216–1222. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704243361704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galasko DR, Peskind E, Clark CM, et al. Antioxidants for Alzheimer disease: a randomized clinical trial with cerebrospinal fluid biomarker measures. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(7):836–841. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen RC, Thomas RT, Grundman M, et al. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. NEJM. 2005;353(24):2379–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loef M, Schrauzer GN, Walach H. Selenium and Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;26(1):81–104. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnaud J, Akbaraly NT, Hininger I, Roussel AM, Berr C. Factors associated with longitudinal plasma selenium decline in the elderly: The EVA Study. J Nutr Biochem. 2007;18(7):482–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao S, Yinlong J, Hall KS, Liang C, Unverzagt FW, Ji R, Murrell JR, Cao J, Shen J, Ma F, Matesan J, Ying B, Cheng Y, Bian J, Li P, Hendrie HC. Selenium level and cognitive function in rural elderly. Chinese Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:955–965. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, Lucia MS, Thompson IM, Ford LG, Parnes HL, Minasian LM, Gaziano JM, Hartline JA, Parsons JK. Effect of Selenium and Vitamin E on Risk of Prostate Cancer and Other Cancers: The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301(1):39–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kryscio RJ, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, et al. A randomized controlled Alzheimer’s disease prevention trial’s evolution into an exposure study: the PREADViSE trial. J Nutrition: Health and Aging. 2013;17(1):72–75. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0083-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kryscio RJ, Mendiondo MS, Schmitt FA, Markesbery WR. Designing a large prevention trial: statistical issues. Stat Med. 2004;23:285–296. doi: 10.1002/sim.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caban-Holt A, Schmitt FA, Runyons CR, et al. Studying the effects of vitamin E and selenium for Alzheimer’s disease prevention: the PREADViSE model. Research and Practice in Alzheimer’s Disease. 2006;11:124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodman PJ, Hartline JA, Tangen CM, et al. Moving a randomized clinical trial into an observational cohort. Clin Trials. 2013;10:131–142. doi: 10.1177/1740774512460345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buschke H, Kuslansky G, Katz M, et al. Screening for dementia with the memory impairment screen. Neurology. 1999;52:231–238. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Jager CA, Budge MM, Clarke R. Utility of TICS-M for the assessment of cognitive function in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psych. 2003;18:318–324. doi: 10.1002/gps.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39(9):1159–1165. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathews M, Abner E, Caban-Holt A, Kryscio R, Schmitt F. CERAD practice effects and attrition bias in a dementia prevention trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:1115–1123. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Powlishta KK, et al. A brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology. 2005;65:559–564. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172958.95282.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kluger A, Ferris SH, Golomb J, Mittelman MS, Reisberg B. Neuropsychological prediction of decline to dementia in nondemented elderly. J Geriatr Psych Neur. 1999 Winter;12(4):168–179. doi: 10.1177/089198879901200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeKosky ST, Williamson JD, Fitzpatrick AL, et al. Gingko biloba for prevention of dementia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:2253–2262. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ADAPT Research Group. Lyketsos CG, Breitner JC, Green RC, et al. Naproxen and celecoxib do not prevent AD in early results from a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;68(21):1800–1808. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260269.93245.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coker LH, Espeland MA, Rapp SR, et al. Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy and Cognitive Outcomes: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS) The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2010;118(0):304–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vella B, Coley N, Ousset PJ, et al. Long term use of standardized Ginkgo biloba extract for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease (GuidAge): a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(10):851–859. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lovell MA, Xiong S, Lyubartseva G, Markesbery WR. Organoselenium (Sel-Plex diet) decreases amyloid burden and RNA and DNA oxidative damage in APP/PS1 mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46(11):1527–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vincenti M, Mandrioli J, Borella P, Michalke B, Tsatsakis A, Finkelstein Y. Selenium neurotoxicity in humans: bridging laboratory and epidemiologic studies. Toxicology Letters. 2014;230:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang GQ, Wang SZ, Zhou RH, Sun SZ. Endemic selenium intoxication of humans in China. Am Jin Nutr. 1983;37(5):872–881. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/37.5.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the selenium and vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) JAMA. 2009;301(1):39–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller ER, 3rd, Pastor-Barriuso R, Dalal D, Riemersma RA, Appel LJ, Guallar E. Meta-analysis: high-dosage vitamin E supplementation may increase all-cause mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Jan 4;142(1):37–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-1-200501040-00110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Mendiondo MS, Marcum JL, Kryscio RJ. Vitamin E and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. Curr Aging Sci. 2011;4(2):158–70. doi: 10.2174/1874609811104020158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fowler NR, Frame A, Perkins AJ, et al. Traits of patients who screen positive for dementia and refuse diagnostic assessment. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;1(2):236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Storandt M, Morris JC. Ascertainment bias in the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(11):1364–1368. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Coats MA, Morris JC. Patient’s rating of cognitive ability using the AD8, a brief informant interview, as a self-rating tool to detect dementia. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(5):725–30. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monteiro IM, Boksay I, Auer SR, Torossian C, Sinaiko E, Reisberg B. Reliability of routine clinical instruments for the assessment of Alzheimer’s disease administered by telephone. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1998;11:18–24. doi: 10.1177/089198879801100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duff K, Beglinger LJ, Adams WH. Validation of the modified Telephone Interview for cognitive status in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and intact elders. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(1):38–43. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181802c54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.