Summary

Environmental and genetic factors seem to play a pathogenetic role in multiple sclerosis (MS). The genetic component is partly suggested by familial aggregation of cases; however, MS families with affected subjects over different generations have rarely been described.

The aim of this study was to report clinical and genetic features of a multigenerational MS family and to perform a review of the literature on this topic.

We describe a multigenerational Italian family with six individuals affected by MS, showing different clinical and neuroradiological findings. HLA-DRB1* typing revealed the presence of the DRB1*15:01 allele in all the MS cases and in 4/5 non-affected subjects. Reports on six multigenerational MS families have previously been published, giving similar results.

The HLA-DRB1*15:01 allele was confirmed to be linked to MS disease in this family; moreover, its presence in non-affected subjects suggests the involvement of other susceptibility factors in the development and expression of the disease, in accordance with the complex disease model now attributed to MS.

Keywords: familial, human leukocyte antigen, multigenerational, multiple sclerosis, review

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory demyelinating and neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system (CNS) (Compston and Coles, 2008). The heterogeneity of MS is well known, and this is seen in the clinical presentation, disease course, disease activity and disability progression (Lublin and Reingold, 1996; Lublin et al., 2014).

The worldwide prevalence of MS is estimated to be 2.5 million cases, varying with latitude, with a lower prevalence found nearer the equator. MS is more common in women than in men, with a female-to-male ratio of 2.3 (Kamm et al., 2014).

The etiology of the disease is unknown and both environmental and genetic factors seem to play a key role in its development. Various environmental factors have been identified, to date season of birth, vitamin D levels, latitude, exposure to the Epstein-Barr virus, vascular comorbidities, smoking (Kamm et al., 2014; Files et al., 2015) and dietary salt intake (Hucke et al., 2015). Interestingly, studies performed on immigrant populations showed that people who migrated before adolescence acquire the risk profile of their new country, whereas those who migrated after adolescence retain that of their country of origin (Kamm et al., 2014).

Various evidence suggests the involvement of a genetic component. MS frequency differs between ethnicities (the highest incidence being found in individuals of northern European origin compared with African and Asian groups), regardless of geographic location (Haines et al., 1998; Stüve et Oksenberg, 2006). Familial aggregation occurs in MS and the estimated overall recurrence rate is 20–22.8% (Ebers et al., 2000; Kamm et al., 2014). The risk changes from 2.77% in first-degree relatives to 1.02% in second-degree relatives and 0.88% in third-degree relatives, compared with 0.3% in the general population (Robertson et al., 1996). Twin studies indicate about 30% concordance for monozygotic twins compared with about 3–5% for dizygotic twins (Haines et al., 1998; Kamm et al., 2014; Files et al., 2015). Furthermore, it has previously been shown that the maternal parent-of-origin effect increases the risk of the disease (Ebers et al., 2004).

All available genetic data suggest that the inheritance model of the pathology is complex; susceptibility is determined by multiple, possibly interacting genes, each exerting small to moderate risk effects (Haines et al., 1998; Vitale et al., 2002; Hafler et al., 2007).

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex on chromosome 6p21.3, was the first MS risk locus identified (Bertrams and Kuwert, 1972; Naito et al., 1972) and it remains the most important one by far (Lill, 2014); in particular, the HLA class II region has the largest influence, with HLA-DRB1*15:01 conferring a threefold increase in MS risk (Kamm et al., 2014; Lill, 2014).

Italy is a high risk area for MS, with Sardinia, in particular, showing the highest frequency (Rosati et al., 1996; Melcon et al., 2014); here, MS has been found to be associated with different HLA-DRB1 alleles, such as DRB1*03:01 and DRB1*04:05 (Marrosu et al., 1997; Cocco et al., 2013), since Sardinians are an ethnically homogeneous population with a genetic structure that is quite different from that of all other Italian and European populations.

Several genomewide association studies have been performed in MS, and they have revolutionized genetic analysis of the disease; more than 100 associated common variants have now been identified, implicating genes involved in immunological processes; many of them have already been associated with other autoimmune diseases (Sawcer et al., 2014). However, recent estimates suggest that the MS risk loci identified to date are able to explain only about a quarter of the reported heritability, most of which is attributable to the HLA locus (Svejgaard, 2008).

Familial MS aggregation is well known; multicase families with affected members found in more than one generation have been reported; it has been suggested that such families may represent an important resource for studying MS, since a higher aggregation of susceptibility loci in such families occurs as compared with the families of sporadic cases (Gourraud et al., 2011). Detailed clinical description of these families is a fundamental preliminary requirement to support such investigations. Here we describe an Italian family that has six members with MS (five females with a definite diagnosis and a male, possibly affected) spanning two, possibly three, generations. Affected and non-affected family members were typed for the HLA-DRB1* locus to test its association with the disease. Furthermore, we performed a review of literature data on MS multigenerational families.

Materials and methods

The proband was examined at MS Center of the Neurological Department at the ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda (Milan, Italy); the other members were submitted to clinical and genetic assessment over time after spontaneously seeking and requesting advice. The proband and all family members who requested genetic testing were carefully counseled after signing an informed consent form approved by the local ethics committee.

The controls in this study were family members with no symptoms, one belonging to the second generation (II:2, 86 years old), three belonging to the third generation (III:1; III:3; III:9; 68, 64 and 54 years old, respectively) and one belonging to the fourth generation (IV:10, 42 years old).

The family history was reconstructed through interviews and examination of the clinical records of each affected and non-affected member, to provide a family pedigree.

MS diagnoses were based on the criteria applicable at the time of diagnosis, i.e., the Poser criteria for subject III:6 (Poser et al., 1983), the McDonald’s 2001 criteria for subject III:10 (McDonald et al., 2001), the McDonald’s 2005 criteria for subjects III:2 and III:4 (Polman et al., 2005) and the McDonald’s 2010 criteria for subject IV:1 (Polman et al., 2011). All MS diagnoses were confirmed using the 2010 revision of the McDonald’s criteria (Polman et al., 2011).

The clinical course was defined according to the first consensus definition of MS clinical courses (Lublin and Reingold, 1996 oppure Lublin et al., 2014). A neuropsychological evaluation was performed in only three family subjects. In particular, the following tests were administered: phonemic fluency test, semantic fluency test, brief history, digit span, Corsi block-tapping test, Rey-Osterrieth complex figure test, attentional matrices, Trail Making tests A & B, Raven matrices test and Beck Depression Inventory test.

Blood samples were collected and DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using standard procedures (Miller et al., 1988). HLA analysis was performed at low and high resolution; in particular, a commercial kit with sequence-specific primers designed to match single alleles was used for PCR-SSP (HLA-Ready Gene DRB Low, Inno-Train, Kronberg im Taunus, Germania) to determine the HLA class II (HLA-DRB1* locus). High-resolution 4-digit typing was carried out using a specific Olerup kit (Olerup, Stockholm, Sweden) (Cristallo et al., 2012). Alleles were assigned on the basis of analysis of the reaction profile, which was defined as the presence or absence of specific bands in addition to the internal control. This was done using the software SCORE which refers to the NCBI dbMHC database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gv/mhc/main.fcgi?cmd=init).

Alleles were named according to current official nomenclature (http://hla.alleles.org/).

MS multigenerational families are defined as those in which there are at least two members affected occurring in different generations. The literature search was performed consulting the main online databases: EMBASE (www.elsevier.com/solutions/embase-biomedical-research), Pubmed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), Scopus (www.scopus.com) and Web of Science (workinfo.com). The search criteria were “multiple sclerosis”, “family”, “multicase”, and “multigenerational”, with no limits of publication years.

Each selected paper, together with its reference list, was carefully evaluated.

Results

Family overview

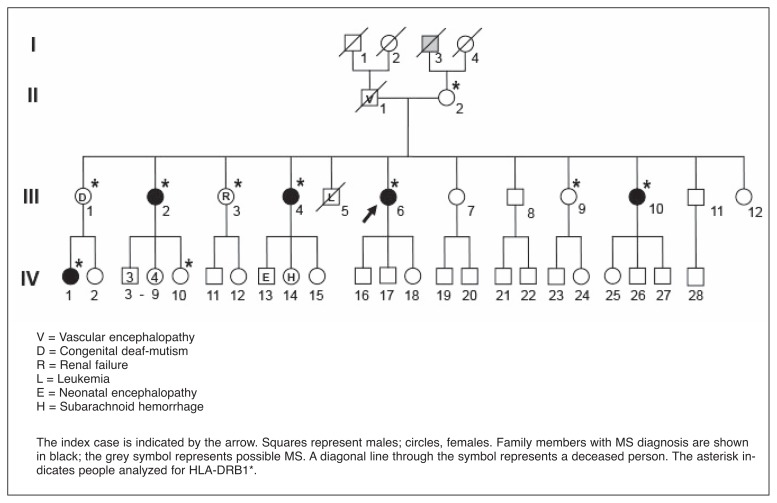

The family originated from a small town with about 8000 inhabitants located in southern Italy; the pedigree is shown in figure 1. It consists of 46 members spanning four generations. No consanguineous marriages were reported.

Figure 1.

The Italian MS family pedigree.

Five females, belonging to generations III and IV, were affected by MS, defined as: progressive with relapse (PR) (III:2), secondary progressive (SP) (III:4; III:10) and relapsing remitting (RR) (III:6; IV:1). Moreover a possible diagnosis of primary progressive (PP) MS was made for a male family member, I:3 (Tab. I).

Table I.

Synopses of MS cases.

| Subject | Sexa | Age at onset (years) | Onset symptom | Time to 2nd relapse (years) | Clinical courseb | Disease Duration (years) | Brain MRIc | Spinal MRIc | Oligoclonal bandsd | Current EDSS scoree | Migration to northern Italy (age, years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I:3 | M | 20 | Paraparesis | - | PP | 30 | NP | NP | NP | died | no |

| III:2 | F | 47 | Paraparesis | - | PR | 15 | >20 | >3 | + | 6.5 | yes (23) |

| III:4 | F | 42 | Leg numbness | 10 | SP | 17 | <9 | extensive | + | 6.5 | no |

| III:6 | F | 19 | Leg numbness | 3 | RR | 40 | <10 | extensive | + | 2.5 | yes (20) |

| III:10 | F | 24 | Facial palsy | 1 | SP | 23 | confluent | extensive | + | 6.5 | no |

| IV:1 | F | 27 | Leg paresis | 1 | RR | 3 | <9 | 1 | + | 2.5 | no |

F: female; M: male.

RR: relapsing remitting; SP: secondary progressive; PR: progressive relapsing.

MRI findings are described; the focal lesion count is reported when possible; NP: not performed.

Oligoclonal bands: (+) positive; (−) negative; NP: not performed.

EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale (Kurtzke, 1983).

Clinical and neuroradiological features of patients are described; information on migration from birth country to northern Italy is also provided.

All patients had MRI findings compatible with MS; brain and spinal lesion load varied.

Six non-MS members were affected by various disorders (Fig. 1); no pathological conditions were reported in the other subjects.

All the members of the first two generations stayed in their place of birth all their lives, while six members of the third generation migrated to northern Italy: two MS (III:2, III:6) and three non-MS (III:3, III:7, III:9) subjects migrated after adolescence, while one healthy member (III:8) migrated at the age of 14 (Tab. I).

The clinical data of the MS cases are summarized in Table I and briefly described below.

- Subject I:3 He died aged 50 years in 1940. He had presented a progressive gait disorder since he was 20 years and was confined to a wheelchair by the age of 33 years. No investigations were performed and a diagnosis of possible PP MS was made on the basis of a review of the medical records recovered.

- Subject III:2 She was born in June 1949. She presented progressive spasticity, painful dysesthesias and urinary disorders by the age of 47 years. Ten years later she was admitted to our hospital for transient diplopia. Brain and spinal MRI showed T2-weighted hyperintense lesions and few T1-weighted enhancing lesions after gadolinium infusion. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) oligoclonal bands (OBs) were detected. Visual evoked potentials (VEPs) were within normal limits. A diagnosis of PR MS was made. Interferon beta-1b was started without benefit. In 2012, she scored 6.5 points on the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) (Kurtzke, 1983); at this time a breast carcinoma was removed.

- Subject III:4 She was born in January 1953. At the age of 42 years she developed abdominal and leg hypoesthesia, with spontaneous remission within three months. Two years later a diagnosis of seronegative spondy-loarthritis and fibromyalgia was made. A further eight years later she reported dizziness and bladder dysfunction. Brain and spinal MRI showed T2-hyperintense lesions and CSF OBs were detected; evoked potentials were not performed. She was treated with immunosuppressive agents for three years. She had further relapses and a progressive worsening of deambulation from the age 55 years. At the last examination her disability score was 6.5 EDSS; some visible cognitive dysfunctions were present, but no specific neuropsychological assessment was performed.

- Subject III:6 (proband) She was born in July 1955. At the age of 19 years she developed transient leg numbness, followed by episodes of paresthesia and diplopia. She was admitted to our hospital in 1999. Brain and spinal MRI showed T2-hyperintense lesions compatible with MS and CSF OBs were found; multimodal evoked potentials were within normal limits. Interferon beta-1a therapy was started. In 2009 a diagnosis of spondy-loarthritis was made. At the last examination, she was relapse free (EDSS score of 2.5). Neuropsychological evaluation showed the presence of visual motor apraxia and a prolonged attention dysfunction; this situation remained stable at follow-up.

- Subject III:10. She was born in June 1964. At the age of 24 years she developed facial palsy and one year later right optic neuritis. Fifteen years later she showed walking impairment and urinary incontinence. Brain and spinal MRI showed T2-hyperintense lesions and CSF OBs were detected. VEP showed mild dysfunction of central visual conduction in response to foveal and parafoveal stimuli in the right eye. Interferon beta-1a therapy was started. She had further relapses and worsening. At the last examination spastic paraparesis was found (EDSS score of 6.5). In 2003 her neuropsychological evaluation showed the same problems manifested by the proband.

- Subject IV:1 She was born in September 1983. At 27 years of age she manifested a right leg paresis. After one year she complained of paraparesis and leg hypoesthesia, which extended to the perineum. Brain and spinal MRI was compatible with active MS. CSF OBs were detected; multimodal evoked potentials were within normal limits. Fingolimod therapy was started after Interferon beta-1a. At the last examination, her EDSS score was 2.5. At the time of diagnosis, no neuropsychological dysfunctions were detected. Migraine with aura was also reported.

HLA genotypes

Ten subjects were analyzed for the HLA-DRB1* locus, five with MS and five not affected.

In the MS subjects, the HLA genotypes were found to be DRB1*15:01, *11 in III:2, III:4, III:6 and III:10 and DRB1*15:01, *16 in IV:1.

In the non-MS individuals, the HLA genotypes were found to be DRB1*15:01, *11 in III:1, III:3, and III:9; DRB1*15:01, *07:01 in II:2 subject, and DRB1*1, *04 in IV:10.

Literature review

To the best of our knowledge, six MS multigenerational families have been reported prior to the one reported herein. Table II summarizes the relative descriptions of pedigree, clinical and genetic findings (Bird, 1975; Vitale et al., 2002; Dyment et al., 2002; Haghighi et al., 2006; Dyment et al., 2008; Binzer et al., 2010).

Table II.

Multigenerational MS families: review of the literature.

| First Author, year | Country | Families (N)a | Members (N)a | MS patients (N)a | Generations (N)a | MS typeb (Na patients) | MS F- MS Mc | Mean age at onset (Range) | HLA findings (MS n/Td) (not-MS n/Td) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bird, 1975 | North America | 1 | 80 | 3 (+1 possible) | 3 | RR (3) (+ 1 PP) | 1–3 | 20 (15–26) | Haplotype 11, W16e (3/3) (1/8) |

|

| |||||||||

| Vitale, 2002 | North America (Dutch Pennsylvania) | 1 | 21 | 7 (+1 possible) | 3 | SP (2) RR (4) UK (1) (+ 1 PP) |

6-2 | 30 (24–37) | DRB1*15f (7/7) (4/11) |

|

| |||||||||

|

Dyment, 2002 Dyment, 2008 |

North America | 1 | 96 | 15 (+1 possible) | 3 (possibly 4) | PP (2) SP (6) RR (7) (+ 1 PP) |

10-6 | 27 (17–49) | DRB1*15g (11/14) |

|

| |||||||||

| Haghighi, 2006 | Western Sweden | 2 | Family A 88 |

7 | 3 | UK | 7-0 | 42 (18–78) | DRB1*15f (7/7) (17/41) |

| Family B 15 |

6 | 3 | UK | 2–4 | 41 (19–61) | DRB1*01:03 (5/5) (5/8) | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Binzer, 2010 | Faroe Islands | 1 | 67 | 14 | 4 | PP (7) RR (5) UK (2) SP (1) RP (1) |

9-5 | 34 (19–51) | DRB1*15f,g (3/6) |

| Present report | Italy | 1 | 46 | 5 (+1 possible) | 2 (possibly 3) | RR (3) (+ 1 PP) | 5-1 | 32 (19–48) | DRB1*15 (5/5) (4/5) |

N: number.

RR: relapsing remitting; SP: secondary progressive; PR: progressive relapsing; PP: primary progressive; UK: unknown.

MS F: MS female; MS M: MS male.

n/T: number of subjects with the reported allele out of the total number of analyzed patients; no information are reported on heterozygous or homozygous state of the allele.

This paper does not allow to compare with the actual HLA classification

The HLA allele is reported according to the current official nomenclature although different names were reported in the original articles (Vitale et al., 2002: DR15; Haghighi et al., 2006: DRB1*02(15), Binzer et al., 2010: DR15).

No data on HLA typing are available for non-affected family members.

Three of the families came from North America (Bird, 1975; Vitale et al., 2002; Dyment et al., 2002; Dyment et al., 2008), two from Sweden (Haghighi et al., 2006) and one from the Faroe Islands (Binzer et al., 2010).

Overall, 52 MS subjects and three possible MS cases over three or four generations were studied. All the patients were adults except for two adolescents, aged 15 and 17 years (Bird, 1975; Dyment et al., 2002). The prevalence of female gender was confirmed in all but two of the families (Bird, 1975; Haghighi et al., 2006). The subjects’ clinical conditions were heterogeneous in terms of MS type and mean age at onset. With regard to MRI, detailed reports were not available.

The HLA pattern was analyzed in the MS cases in all the families and the HLA-DRB1*15 allele was detected in most of them; however, in those reports in which HLA analysis was extended to all the family (Vitale et al., 2002; Haghighi et al., 2006; Binzer et al., 2010), the same allele was found also in some family members not affected by MS.

Discussion

We have here described clinical, MRI and HLA-DRB1 findings in an Italian family in which six out of 46 members were found to be affected by MS (five definite and one possible). Their clinical presentation was heterogeneous in terms of type of MS, age and symptoms at onset and disability, as well as MRI lesion load. All the definite cases were females while the individual with a possible diagnosis of MS was male. The five analyzed cases all carried the HLA-DRB1*15:01 allele.

All MS cases shared the same environmental risk factors, since the only two who migrated did so after adolescence. No correlation between the occurrence of MS and the season of birth was found in our family, although previous data suggested that the highest rate of MS occurred in people born in May and the lowest in those born during November (Files et al., 2015). The non-affected subjects analyzed were adults with an average age of 63 years, greater than that commonly reported at disease onset; all carried the HLA-DRB1*15:01 allele except the youngest (42 years old).

MS families with more than three affected individuals have rarely been described. In the data set described by Haines et al. (1998), referring to 98 Caucasian multiplex families, 14% had four or more affected individuals. Moreover, among 28,000 MS cases collected in the Canadian population, 10% of families had two or three affected cases, 0.2% four or five and five families had seven–nine cases (Dyment et al., 2008).

Pedigrees with more than two consecutive generations are even more rarely described.

Our review of the literature disclosed reports on clinical and HLA findings in six MS multigenerational families, published prior to the present one (Tab. II) (Bird, 1975; Vitale et al., 2002; Dyment et al., 2002; Haghighi et al., 2006; Dyment et al., 2008; Binzer et al., 2010). These families showed similar clinical heterogeneity to that found in our family; it is also to be noted that, with the exception of two studies, the gender distribution showed a female predominance (Tab. II).

Only Dyment et al. (2002) and Vitale et al. (2002) reported MRI findings, without providing detailed descriptions. In our cases, MRI lesion load was found to be consistent with clinical phenotype and disease duration.

An association between MS and the HLA-DRB1*15 allele was found in all reports, except for the family described by Bird (1975), supporting its role as strong susceptibility factor. The frequency of this allele within the family reported by Dyment et al. (2008) was 79% in MS cases and 38% in the unaffected subjects (Dyment et al., 2008). On the contrary, we detected the HLA-DRB1*15 allele in four out of five non-affected subjects, including the proband’s mother (II:2) and three adult sisters, who are currently healthy.

It is conceivable that a high genetic burden may be operating within families with co-affected relatives (Gourraud et al., 2012), while it is probable that, according to the complex disease model, other factors (genetic and non-genetic) play a role in determining the expression of the disease (Dyment et al., 2012; Sawcer et al., 2014; Barizzone et al., 2015; Hollenbach and Oksenberg 2015). A more extensive molecular analysis has been planned in our multigenerational MS family in order to identify genes/genetic variants with a possible modifier role in this disease.

Footnotes

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- Barizzone N, Zara I, Sorosina M, et al. The burden of multiple sclerosis variants in continental Italians and Sardinians. Mult Scler. 2015;21:1385–1395. doi: 10.1177/1352458515596599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrams J, Kuwert E. HL-A antigen frequencies in multiple sclerosis. Significant increase of HL-A3, HL-A10 and W5, and decrease of HL-A12. Eur Neurol. 1972;7:74–78. doi: 10.1159/000114414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binzer S, Imrell K, Binzer M, et al. Multiple sclerosis in a family on the Faroe Islands. Acta Neurol Scand. 2010;121:16–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird TD. Apparent familial multiple sclerosis in three generations. Report of a family with histocompatibility antigen typing. Arch Neurol. 1975;32:414–416. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1975.00490480080009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco E, Murru R, Costa G, et al. Interacion between HLA-DRB1–DQB1 haplotypes in Sardinian multiple sclerosis population. Plos One. 2013;8:e59790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1502–1517. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristallo AF, Lando G, Rossi U, et al. HLA polymorphisms in Lombardy defined by high-resolution typing methods. Riv Ital Med Lab. 2012;8:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Dyment DA, Cader MZ, Willer CJ, et al. A multigenerational family with multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2002;125:1474–1482. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyment DA, Cader MZ, Herrera BM, et al. A genome scan in a single pedigree with a high prevalence of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:158–162. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.122705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyment DA, Cader MZ, Chao MJ, et al. Exome sequencing identifies a novel multiple sclerosis susceptibility variant in the TYK2 gene. Neurology. 2012;79:406–411. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182616fc4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebers GC, Koopman WJ, Hader W, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study. 8: familial multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2000;123:641–649. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.3.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebers GC, Sadovnick AD, Dyment DA, et al. Parent-of-origin effect in multiple sclerosis: observations in half-siblings. Lancet. 2004;363:1773–1774. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Files DK, Jausurawong T, Katrajian R, et al. Multiple sclerosis. Prim Care. 2015;42:159–175. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourraud PA, McElroy JP, Caillier SJ, et al. Aggregation of multiple sclerosis genetic risk variants in multiple and single case families. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:65–74. doi: 10.1002/ana.22323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourraud PA, Harbo HF, Hauser SL, et al. The genetics of multiple sclerosis: an up-to-date review. Immunol Rev. 2012;248:87–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafler DA, Compston A, Sawcer S, et al. Risk alleles for multiple sclerosis identified by a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:851–862. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi S, Andersen O, Nilsson S, et al. A linkage study in two families with multiple sclerosis and healthy members with oligoclonal CSF immunopathy. Mult Scler. 2006;12:723–730. doi: 10.1177/1352458506070972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines JL, Terwedow HA, Burgess K, et al. Linkage of the MHC to familial multiple sclerosis suggests genetic heterogeneity. The Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Group Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1229–1234. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.8.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbach JA, Oksenberg JR. The immunogenetics of multiple sclerosis: A comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2015;64:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hucke S, Wiendl H, Klotz L. Implications of dietary salt intake for multiple sclerosis pathogenesis. Mult Scler. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1352458515609431. pii: 1352458515609431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamm CP, Uitdehaag BM, Polman CH. Multiple sclerosis: current knowledge and future outlook. Eur Neurol. 2014;72:132–141. doi: 10.1159/000360528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch-Henriksen N, Sørensen PS. The changing demographic pattern of multiple sclerosis epidemiology. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:520–532. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS) Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1452. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.11.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lill CM. Recent advances and future challenges in the genetics of multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol. 2014;5:130. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lublin FD, Reingold SC. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology. 1996;46:907–911. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.4.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83:278–286. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrosu MG, Murru MR, Costa G, et al. Multiple sclerosis in Sardinia is associated and in linkage dise-quilibrium with HLA-DR3 and -DR4 alleles. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:454–457. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9297(07)64074-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:121–127. doi: 10.1002/ana.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcon MO, Correale J, Melcon CM. Is it time for a new global classification of multiple sclerosis? J Neurol Sci. 2014;344:171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito S, Namerow N, Mickey MR, et al. Multiple sclerosis: association with HL-A3. Tissue Antigens. 1972;2:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1972.tb00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “Mc-Donald Criteria”. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:840–846. doi: 10.1002/ana.20703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:292–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poser CM, Paty DW, Scheinberg L, et al. New diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines for research protocols. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:227–231. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson NP, Fraser M, Deans J, et al. Age-adjusted recurrence risks for relatives of patients with multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1996;119:449–455. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.2.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosati G, Aiello I, Pirastru MI, et al. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Northwestern Sardinia further evidence for higher frequency in Sardinians compared to other Italians. Neuroepidemiol. 1996;15:10–19. doi: 10.1159/000109884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawcer S, Franklin RJM, Ban M. Multiple sclerosis genetics. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:700–709. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stüve O, Oksenberg J. Multiple Sclerosis Overview. 2006. [Accessed 28 December 2015]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20301492.

- Svejgaard A. The immunogenetics of multiple sclerosis. Immunognetics. 2008;60:275–286. doi: 10.1007/s00251-008-0295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale E, Cook S, Sun R, et al. Linkage analysis conditional on HLA status in a large North American pedigree supports the presence of a multiplvite sclerosis susceptibility locus on chromosome 12p12. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:295–300. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]