Abstract

Background

Temporary abdominal closure (TAC) may be performed for cirrhotic patients undergoing emergent laparotomy. The effects of cirrhosis on physiologic parameters, resuscitation requirements, and outcomes following TAC are unknown. We hypothesized that cirrhotic TAC patients would have different resuscitation requirements and worse outcomes than noncirrhotic patients.

Methods

We performed a 3-year retrospective cohort analysis of 231 patients managed with TAC following emergent laparotomy for sepsis, trauma, or abdominal compartment syndrome. All patients were initially managed with negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) TAC with intention for planned relaparotomy and sequential abdominal closure attempts at 24- to 48-h intervals.

Results

At presentation, cirrhotic patients had higher incidence of acidosis (33% versus 17%) and coagulopathy (87% versus 54%) than noncirrhotic patients. Forty-eight hours after presentation, cirrhotic patients had a persistently higher incidence of coagulopathy (77% versus 44%) despite receiving more fresh frozen plasma (10.8 units versus 4.4 units). Cirrhotic patients had higher NPWT output (4427 mL versus 2375 mL) and developed higher vasopressor infusion rates (57% versus 29%). Cirrhotic patients had fewer intensive care unit-free days (2.3 versus 7.6 days) and higher rates of multiple organ failure (64% versus 34%), in-hospital mortality (67% versus 21%), and long-term mortality (80% versus 34%) than noncirrhotic patients.

Conclusions

Cirrhotic patients managed with TAC are susceptible to early acidosis, persistent coagulopathy, large NPWT fluid losses, prolonged vasopressor requirements, multiple organ failure, and early mortality. Future research should seek to determine whether TAC provides an advantage over primary fascial closure for cirrhotic patients undergoing emergency laparotomy.

Keywords: Temporary abdominal closure, Damage control surgery, Laparotomy, Open abdomen, Cirrhosis, Ascites

Introduction

Cirrhotic patients who undergo abdominal surgery have poor outcomes. Following trauma laparotomy, cirrhotic patients have higher mortality than noncirrhotic patients (45% versus 24%) when controlling for age, gender, mechanism of injury, and injury severity.1 Although cirrhosis does not appear to increase the likelihood of failing nonoperative management of blunt liver injury, cirrhotic patients who fail nonoperative management and require a laparotomy have higher mortality than noncirrhotic counterparts.2 Emergency general surgery is also hazardous in the cirrhotic patient.3 A review of non-injured patients with cirrhosis undergoing laparotomy reports 46% mortality for nonelective cases compared to 12% for elective cases.4 Urgent and emergent abdominal wall herniorraphy among cirrhotic patients has been independently associated with increased morbidity (OR 7.3, 95% CI: 1.4–38) and mortality (OR 10.8, 95% CI: 1.3–91).5

Damage control laparotomy has become a preferred management strategy for patients with severely deranged physiology who require emergency abdominal surgery. This includes the utilization of temporary abdominal closure (TAC) techniques which utilize a protective barrier over the viscera, negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), and techniques to prevent lateral retraction of the fascia while the abdomen remains open.6–8 Definitive surgical repair is deferred to facilitate physiologic resuscitation to minimize the chances of progression to multiple organ failure.9–12 In patients with intra-abdominal sepsis, TAC may facilitate early diagnosis and treatment of residual infection, remove cytokine-rich peritoneal fluid, and defer anastomosis until physiologic optimization.13,14 Among injured patients, TAC may be appropriate following administration of more than 10 units of packed red blood cells, more than 15 L of crystalloid, and presence of acidosis, coagulopathy, and hypothermia.9,11,12,15–17 Prevention and treatment of abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) may involve decompressive laparotomy followed by TAC if immediate primary fascial closure is not safe or feasible.18

Data regarding the utilization of damage control management and TAC in cirrhotic patients are limited to a report of nine patients with posttraumatic ACS, which included two cirrhotic patients.19 One cirrhotic patient underwent primary fascial closure and survived, and the other was managed with absorbable mesh bridge placement and had persistent drainage of ascites for 6 wk before succumbing to sepsis and pulmonary failure.19 Owing to the paucity of literature regarding TAC in cirrhotic patients, management strategies must be extrapolated from studies that may not be generalizable to this population. The purpose of this study was to characterize the effects of cirrhosis on physiologic parameters and outcomes for TAC patients. We hypothesized that cirrhotic TAC patients would have different resuscitation requirements and worse outcomes than noncirrhotic TAC patients.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of patients managed with TAC for intraabdominal sepsis, traumatic injury, or ACS at our institution during a 3-year period ending June 2015. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained. Patients were identified by CPT code modifiers 58 (planned reoperation) and 78 (unplanned reoperation) for all surgeons in the Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. Inclusion criteria were age ≥18, by TAC with NPWT for intraabdominal sepsis, traumatic injury, or ACS, and survival for at least 24 hours following presentation. Patients who had their initial exploratory laparotomy at an outside facility and those with preexisting intestinal fistulas were excluded. Cases of necrotizing pancreatitis were excluded to avoid the confounding effects of significant differences in the preoperative and postoperative courses for this disease process.

All patients were initially managed with TAC per surgeon discretion with intention for planned relaparotomy and sequential abdominal closure attempts at 24- to 48-hour interval. Both commercial and vacuum pack dressings were used for NPWT. Critical care management decisions were at the discretion of the attending surgeon and attending intensivist. If primary fascial closure was not safe or feasible following completion of diagnostic and therapeutic objectives, the fascia was sequentially closed with simple interrupted or figure-of-eight sutures placed at the cranial and caudal portions of the fasciotomy until further closure would result in excessive fascial tension or pathologically elevated airway pressures.

Hypothermia was defined as Tmin <35.0°C. Acidosis was defined as pH < 7.20. Lactic acidosis was defined as lactic acid >4 mmol/L. Coagulopathy was defined as international normalized ratio (INR) > 1.5 or coagulopathy on thromboelastograph (TEG) (rapid TEG with at least 2 of 4 conditions: activated clotting time [ACT] > 142 seconds [s], clot formation [K] time >143 s, alpha angle <64°, and maximum amplitude [MA] <52 mm; or standard TEG with at least 2 of 4 conditions: reaction time >600 s, K time >180 s, alpha angle <53°, and MA <50 mm).20 Patients were classified as cirrhotic if they had any of the following: biopsy proven cirrhosis, liver nodularity on imaging studies or intraoperative exploration in conjunction with laboratory value evidence of cirrhosis (elevated INR and thrombocytopenia), or cirrhosis noted as an active disease in the electronic medical record. Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores were calculated for cirrhotic patients on presentation and 48 h later as defined by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. The Child-Pugh score could not be calculated because it was difficult to consistently and accurately determine whether NPWT output was composed of blood, ascites, or both based on review of the electronic medical record. Acute respiratory distress syndrome was defined according to Berlin criteria.21 Acute kidney injury (AKI) was defined as a 2-fold increase in serum creatinine.22 Multiple organ failure (MOF) was defined as dysfunction or failure of at least two organ systems such that homeostasis could not be maintained without intervention.23,24 Long-term follow-up was restricted to post-admission clinic visits and hospitalizations at our institution (follow-up range 3 months-3 years).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY) to calculate one-way analysis of variance, Fisher’s Exact test, and the Kruskal–Wallis test as appropriate in comparing cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients. Data was reported as mean ± standard error, n (%), or median [interquartile range] as appropriate. Correlations between MELD score and outcomes were assessed by Pearson’s coefficient r. Predictors of in-hospital mortality were identified by performing univariate analysis to identify those factors with significant correlation (r > 0.2, P < 0.05) to the outcome variable and eliminate factors with collinearity to other independent variables. Selected factors were entered into a multiple logistic regression equation. Confidence intervals for regression variables were set at 95%, and significance was set at α = 0.05.

Results

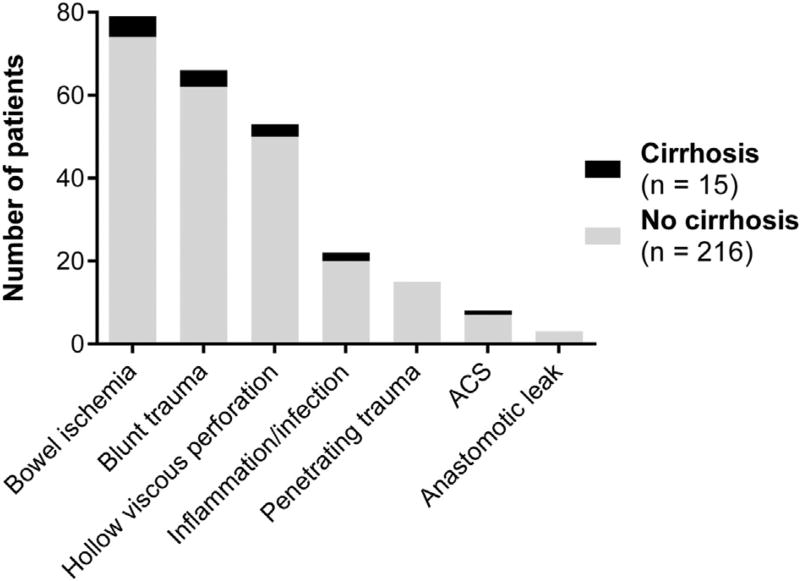

Two hundred and thirty-one patients were included. There were fifteen cirrhotic patients that were evenly distributed among primary diagnoses (P = 0.881) (Fig. 1). Cirrhotic patients had higher rates of acidemia, lactic acidosis, and coagulopathy at presentation (Table 1). Eleven out of fifteen cirrhotic patients (73%) had ascites at the time of presentation. Forty-eight hours after presentation, rates of acidemia were similar between groups, but lactic acidosis continued to disproportionately affect cirrhotic patients (Table 2). Coagulopathy persisted at higher rates among cirrhotic patients despite the fact that they received more fresh frozen plasma than noncirrhotic patients. Of the 125 patients with coagulopathy at initial presentation, 116 had INR >1.5, 47 of these patients also had coagulopathy on TEG, and nine had coagulopathy on TEG alone. Of the 88 patients with coagulopathy at 48 hours, 82 had INR >1.5, 33 of these patients also had coagulopathy on TEG, and six patients had coagulopathy on TEG alone.

Fig. 1.

Primary diagnosis at presentation.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at presentation.

| Baseline characteristics | Cirrhotic (n = 15) |

Not cirrhotic (n = 216) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 55 ± 1.1 | 55 ± 3.1 | 0.994 |

| Male | 9 (60%) | 121 (56%) | 0.796 |

| Hypothermia (Tmin < 35.0°C) | 4 (27%) | 49 (23%) | 0.723 |

| Acidosis (pH < 7.20) | 5 (33%) | 37 (17%) | 0.013* |

| Lactic acidosis (lactic acid > 4.0 mmol/L) | 9 (60%) | 52 (24%) | 0.002* |

| Coagulopathy (per TEG and/or INR > 1.5) | 13 (87%) | 112 (52%) | 0.013* |

| Vasopressor infusion | 9 (60%) | 84 (39%) | 0.110 |

| Solid organ resection or repair | 3 (20%) | 44 (20%) | 0.973 |

| Bowel resection or repair | 8 (53%) | 132 (61%) | 0.551 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard error or n (%).

P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics 48 h after presentation.

| Resuscitation parameters | Cirrhotic (n = 14) | Not cirrhotic (n = 214) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothermia (Tmin < 35.0°C) | 1 (7%) | 7 (3%) | 0.446 |

| Acidemia (pH < 7.20) | 1 (7%) | 5 (2%) | 0.295 |

| Lactic acidosis (lactic acid > 4.0 mmol/L) | 5 (36%) | 25 (12%) | 0.015* |

| Coagulopathy (per TEG and/or INR > 1.5) | 10 (71%) | 78 (36%) | 0.022* |

| Vasopressor infusion | 8 (57%) | 61 (29%) | 0.024* |

| Net fluid balance (mL) | 8432 [5742–8432] | 6692 [4141–9637] | 0.406 |

| Total crystalloid administration (mL) | 8477 [5909–10,290] | 7516 [5942–9590] | 0.870 |

| NPWT output (mL) | 3305 [1695–7300] | 1850 [1055–3200] | 0.030* |

| Red blood cell transfusions (units) | 9.8 ± 6.4 | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 0.103 |

| Plasma transfusions (units) | 10.8 ± 6.3 | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 0.031* |

Data are presented as n (%), median (interquartile range), or mean ± standard error.

P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Total NPWT output was significantly higher in the cirrhotic group. Cirrhotic patients had also had higher vasopressor infusion rates 48 hours after presentation, a difference that was not present on admission (Tables 1 and 2). At 48 hours, net fluid balance was more positive among cirrhotic patients who suffered in-hospital mortality compared to cirrhotic patients who survived (10,578 mL [6272–13,712] versus 6495 mL [3773–11,450]), though the sample sizes were small (n = 10 versus n = 5), and the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.317).

At presentation, cirrhotic patients had average MELD score 17.8 ± 1.1. Forty-eight hours later, average MELD among cirrhotics had increased to 18.7 ± 1.7. Although MELD score at initial laparotomy was not associated with NPWT fluid loss (r = 0.186, P = 0.507), MELD at 48 hours and the change in MELD score from initial laparotomy to 48 hours each correlated directly with NPWT output at 48 hours (r = 0.613, P = 0.015 and r = 0.733, P = 0.002, respectively). MELD scores at these time points were not associated with in-hospital mortality. Adherence to our protocol of postdamage control relaparotomy within 24–48 hours was lower in cirrhotic patients. Within 48 hours, 94% (198/211) of noncirrhotic patients underwent relaparotomy, compared to 79% (11/14) in the cirrhotic group (P = 0.031).

Rates of multiple organ failure and in-hospital mortality were significantly higher in the cirrhotic group (Table 3). Among the 11 cirrhotic patients who achieved primary fascial closure, there were six inpatient mortalities; all four cirrhotic patients who did not achieve fascial closure died in the hospital (54% versus 100%, P = 0.231). Of the ten cirrhotic patients who died during admission, admission diagnoses included blunt trauma (n = 3), bowel ischemia (n = 3), hollow viscous perforation (n = 2), suppurative peritonitis (n = 1), and ACS (n = 1). Cirrhosis was an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality (OR 8.3, 95% CI: 2.2–31) in a multivariate model including two other factors that were associated with in-hospital mortality on univariate analysis: the presence of a vasopressor infusion 48 h after initial laparotomy, and successful primary fascial closure, which was protective against mortality (Table 4). Together, these factors formed a model which was highly significant [χ2(3) = 65.4, P < 0.001], explained 38% of the variability in mortality rates (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.38), and correctly classified 85% of all cases. Cirrhotic patients also had higher long-term mortality (80% versus 34%, P = 0.001).

Table 3.

Patient characteristics at discharge.

| Outcomes | Cirrhotic (n = 15) |

Not cirrhotic (n = 216) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary fascial closure | 11 (73%) | 154 (71%) | 0.866 |

| Days to primary fascial closure | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 0.828 |

| Fascial dehiscence | 0 (0%) | 11 (5%) | 0.345 |

| Intestinal fistula | 0 (0%) | 6 (3%) | 0.513 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 5 (33%) | 33 (15%) | 0.052 |

| Acute kidney injury | 8 (53%) | 77 (36%) | 0.076 |

| Multiple organ failure | 9 (60%) | 71 (33%) | 0.020* |

| Days on mechanical ventilation | 11 [8–25] | 9 [4–17] | 0.213 |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 14 [11–33] | 14 [5–25] | 0.440 |

| ICU-free days | 0 [0–3] | 4 [1–10] | 0.001* |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 14 [11–39] | 20 [9–35] | 0.831 |

| Mortality | 10 (67%) | 46 (21%) | <0.001* |

Data are presented as n (%), mean ± standard error, or median (interquartile range).

P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Table 4.

Predictors of in-hospital mortality.

| Factors | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis | 8.3 | 2.2–31 | 0.002* |

| Vasopressor infusion at 48 h | 6.0 | 2.9–12 | <0.001* |

| Primary fascial closure | 0.2 | 0.1–0.4 | <0.001* |

P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Discussion

Our data show that cirrhotic patients that undergo damage control laparotomy and TAC have different resuscitation requirements and worse outcomes than noncirrhotic patients. This included persistent lactic acidosis, coagulopathy, progression to multiple organ failure, and inpatient mortality. Although serum pH improved significantly over the first 48 hours of resuscitation in both groups, lactic acid levels remained elevated in the cirrhotic cohort. This may be explained in two ways. First, renal and pulmonary compensatory mechanisms may have corrected serum pH, whereas lactic acid clearance progressed at a more indolent pace among cirrhotic patients, given that hepatic metabolism accounts for about 40%–50% of lactate clearance.25 Second, intensive care providers often correct serum pH with sodium bicarbonate administration when pH ≤ 7.15, which may increase serum lactate levels by restoring glycolytic pathways.26,27

This is typically done to raise serum pH to a level at which catecholamines may function optimally, which is relatively common in clinical practice despite a paucity of supporting evidence.28 Although intravenous sodium bicarbonate has been associated with decreased intracellular and cerebrospinal fluid pH and adverse effects on systemic and myocardial oxygen utilization, a systematic review of sodium bicarbonate for patients with lactic acidosis demonstrated no significant changes in cardiac output, morbidity, ormortality.29–31 Human studies have not consistently demonstrated that severe acidosis adversely affects hemodynamics, and sodium bicarbonate administration has not shown clear benefit or harm for severely acidotic patients.32 Therefore, our general practice of administering sodium bicarbonate when pH ≤ 7.15 likely did not impact outcomes but may have accounted for differences in serum pH and lactate trends during resuscitation.

As expected, cirrhotic patients were more commonly coagulopathic than noncirrhotic patients and received more fresh frozen plasma transfusions. Cirrhosis is associated with increased risk for bleeding and thromboembolism due to complex interactions among coagulation and anticoagulation factors as well as fibrinolytic and antifibrinolytic pathways, with a typical phenotype of clotting activation followed by hyperfibrinolysis and prolonged bleeding time.33–35 Platelet counts are not very useful because they only predict bleeding complications at extremely low levels, and cirrhotic patients develop high plasma von Willebrand factor levels to compensate for thrombocytopenia, such that severe thrombocytopenia likely contributes to bleeding diathesis primarily by decreasing plasma thrombin levels.34,36 Fortunately, any physiologically significant effects of severe thrombocytopenia on thrombin should be manifested on TEG. TEG has been endorsed for effectively evaluating platelet function in the context of portal hypertension and antiplatelet therapy use, although high-quality evidence is lacking.37 INR remains a commonly used test in detecting coagulopathy for cirrhotic patients despite the fact that INR standardization of prothrombin time may be compromised in the presence of cirrhosis.38 Therefore, this study used a combination of TEG and INR values to assess coagulopathy.

Evolving recommendations for managing bleeding and coagulopathy in the cirrhotic patient include restrictive PRBC transfusion strategies and avoidance of prophylactic fresh frozen plasma administration.39 This approach avoids high volume loads and the adverse effects of blood product administration.39 In our study, PRBC transfusions were similar between cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients, and it is unclear whether higher FFP transfusion rates among cirrhotic patients reflected prophylactic administration, therapeutic use, or a combination of the two. Unfortunately, the nature of NPWT output (i.e., bloody versus nonbloody) could not be accurately determined retrospectively.

Although vasopressor infusion rates were similar between groups at presentation, cirrhotic patients had significantly higher vasopressor requirements 48 h after presentation. Portal hypertension is associated with fluid sequestration in the peritoneal cavity and arteriolar vasodilation disproportionately affecting the splanchnic vasculature, resulting in relative systemic arterial hypotension and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.40–42 Together, these phenomena may account for increased vasopressor utilization among cirrhotic TAC patients. Higher NPWT output in the cirrhosis group supports this theory, given that the majority of fluid output was probably ascites. It is unclear why cirrhotic patients experienced longer delays between initial laparotomy and first relaparotomy. Because the prevalence of coagulopathy at 48 hours was higher among cirrhotic patients, it seems plausible that relaparotomy may be have been delayed to correct coagulopathy.

Of all variables collected, cirrhosis was the strongest predictor of increased in-hospital mortality among TAC patients. Vasopressor infusion at 48 hours was also strongly associated with in-hospital mortality, and the magnitude of this effect appears to be similar between cirrhotic TAC patients in this study (OR 6.0, 95% CI: 2.9–12) and cirrhotic medical intensive care unit patients (OR 6.6, 95% CI: 3.7–12) as previously reported.43 Notably, the multivariate model did not explain 62% of the observed variability in mortality, suggesting that parameters with collinearity to model covariates and unmeasured factors had a strong influence on mortality. Similar primary fascial closure rates, fascial dehiscence, and intestinal fistula formation between cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients at the time of discharge may be due to effects of unequal in-hospital mortality between cohorts.

The major limitations of this study are its retrospective design, small number of cirrhotic patients (n = 15), inability to capture fibrinolysis on TEG, lack of robust long-term follow-up, and propensity to generate false positive results by making multiple comparisons and overfitting prediction models. Unfortunately, our electronic medical record does not quantify fibrinolytic TEG parameters. Long-term follow-up was restricted to postadmission clinic visits and hospitalizations at our institution. The type I error rate was limited as much as possible by performing analyses driven by our central hypothesis and avoiding subgroup analysis. In addition, the inclusion of both emergency general surgery and trauma patients introduces heterogeneity into the analysis. Unfortunately, a more narrow study population would further reduce the number of cirrhotic patients and would not allow for meaningful comparisons. Because outcomes following TAC in cirrhotic patients appear to be worse than outcomes previously reported for cirrhotic patients undergoing emergency laparotomy, in the future, we will avoid performing TAC for cirrhotic patients whenever possible and recognize that traditional indications for TAC may not be generalizable to this patient population.1,4

Conclusions

Among patients managed with TAC after emergent laparotomy for intraabdominal sepsis, trauma, or ACS, cirrhosis was associated with early acidosis and coagulopathy. Cirrhotic patients had higher vasopressor utilization rates, fresh frozen plasma transfusion requirements, and NPWT fluid losses within 48 hours of initial laparotomy. Cirrhosis was associated with increased incidence of multiple organ failure as well as short- and long-term mortality following TAC. Future research should seek to determine whether cirrhotic patients benefit from TAC as opposed to primary fascial closure at the time of initial laparotomy.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Cindy Scalamonti, CSTR for her assistance in maintaining, accessing, and assuring the quality of our institutional data registry. T.J.L. contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript composition. J.R.J., C.A.C., R.S.S., and P.A.E. contributed to data interpretation and provided critical revisions. F.A.M., A.M.M., and S.C.B. contributed to study design, data interpretation, and provided critical revisions. The authors were supported in part by grants P30 AG028740 (S.C.B.) awarded by the National Institute on Aging and by R01 GM105893-01A1 (A.M.M.), R01 GM113945-01 (P.A.E.), and P50 GM111152–01 (S.C.B., F.A.M., A.M.M., and P.A.E.) awarded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS). T.J.L. was supported by a postgraduate training grant (T32 GM-08721) in burns, trauma, and perioperative injury by NIGMS.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest.

This work was presented at the 36th Annual Surgical Infection Society in Palm Beach, Florida.

References

- 1.Demetriades D, Constantinou C, Salim A, et al. Liver cirrhosis in patients undergoing laparotomy for trauma: effect on outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:538–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barmparas G, Cooper Z, Ley EJ, Askari R, Salim A. The effect of cirrhosis on the risk for failure of nonoperative management of blunt liver injuries. Surgery. 2015;158:1676–1685. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christmas AB, Wilson AK, Franklin GA, et al. Cirrhosis and trauma: a deadly duo. Am Surg. 2005;71:996–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doberneck RC, Sterling WA, Jr, Allison DC. Morbidity and mortality after operation in nonbleeding cirrhotic patients. Am J Surg. 1983;146:306–309. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(83)90402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andraus W, Pinheiro RS, Lai Q, et al. Abdominal wall hernia in cirrhotic patients: emergency surgery results in higher morbidity and mortality. BMC Surg. 2015;15:65. doi: 10.1186/s12893-015-0052-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atema JJ, Gans SL, Boermeester MA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the open abdomen and temporary abdominal closure techniques in non-trauma patients. World J Surg. 2015;39:912–925. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2883-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pliakos I, Papavramidis TS, Mihalopoulos N, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure in severe abdominal sepsis with or without retention sutured sequential fascial closure: a clinical trial. Surgery. 2010;148:947–953. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cothren CC, Moore EE, Johnson JL, Moore JB, Burch JM. One hundred percent fascial approximation with sequential abdominal closure of the open abdomen. Am J Surg. 2006;192:238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burch JM, Ortiz VB, Richardson RJ, et al. Abbreviated laparotomy and planned reoperation for critically injured patients. Ann Surg. 1992;215:476–483. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199205000-00010. discussion 483–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rotondo MF, Schwab CW, McGonigal MD, et al. ‘Damage control’: an approach for improved survival in exsanguinating penetrating abdominal injury. J Trauma. 1993;35:375–382. discussion 382–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaz JJ, Jr, Cullinane DC, Dutton WD, et al. The management of the open abdomen in trauma and emergency general surgery: part 1-damage control. J Trauma. 2010;68:1425–1438. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181da0da5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore EE, Thomas G. Orr Memorial Lecture. Staged laparotomy for the hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy syndrome. Am J Surg. 1996;172:405–410. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(96)00216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez D, Wildi S, Demartines N, et al. Prospective evaluation of vacuum-assisted closure in abdominal compartment syndrome and severe abdominal sepsis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:586–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sartelli M, Abu-Zidan FM, Ansaloni L, et al. The role of the open abdomen procedure in managing severe abdominal sepsis: WSES position paper. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:35. doi: 10.1186/s13017-015-0032-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreis BE, de Mol van Otterloo AJ, Kreis RW. Open abdomen management: a review of its history and a proposed management algorithm. Med Sci Monit. 2013;19:524–533. doi: 10.12659/MSM.883966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatch QM, Osterhout LM, Ashraf A, et al. Current use of damage-control laparotomy, closure rates, and predictors of early fascial closure at the first take-back. J Trauma. 2011;70:1429–1436. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31821b245a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stone HH, Strom PR, Mullins RJ. Management of the major coagulopathy with onset during laparotomy. Ann Surg. 1983;197:532–535. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198305000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coccolini F, Biffl W, Catena F, et al. The open abdomen, indications, management and definitive closure. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:32. doi: 10.1186/s13017-015-0026-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayberry JC, Welker KJ, Goldman RK, Mullins RJ. Mechanism of acute ascites formation after trauma resuscitation. Arch Surg. 2003;138:773–776. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.7.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kashuk JL, Moore EE, Johnson JL, et al. Postinjury life threatening coagulopathy: is 1:1 fresh frozen plasma:packed red blood cells the answer? J Trauma. 2008;65:261–270. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31817de3e1. discussion 270–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Force ADT, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, et al. Acute renal failure - definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8:R204–R212. doi: 10.1186/cc2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore FA, Moore EE. Evolving concepts in the pathogenesis of postinjury multiple organ failure. Surg Clin North Am. 1995;75:257–277. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46587-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shangraw RE. Metabolic issues in liver transplantation. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2006;44:1–20. doi: 10.1097/00004311-200604430-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutton JR, Jones NL, Toews CJ. Effect of PH on muscle glycolysis during exercise. Clin Sci (lond) 1981;61:331–338. doi: 10.1042/cs0610331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hood VL, Tannen RL. Protection of acid-base balance by pH regulation of acid production. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:819–826. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809173391207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraut JA, Kurtz I. Use of base in the treatment of acute severe organic acidosis by nephrologists and critical care physicians: results of an online survey. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2006;10:111–117. doi: 10.1007/s10157-006-0408-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritter JM, Doktor HS, Benjamin N. Paradoxical effect of bicarbonate on cytoplasmic pH. Lancet. 1990;335:1243–1246. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91305-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraut JA, Kurtz I. Use of base in the treatment of severe acidemic states. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:703–727. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.27688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bersin RM, Chatterjee K, Arieff AI. Metabolic and hemodynamic consequences of sodium bicarbonate administration in patients with heart disease. Am J Med. 1989;87:7–14. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(89)80476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimmoun A, Novy E, Auchet T, Ducrocq N, Levy B. Hemodynamic consequences of severe lactic acidosis in shock states: from bench to bedside. Crit Care. 2015;19:175. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0896-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nusrat S, Khan MS, Fazili J, Madhoun MF. Cirrhosis and its complications: evidence based treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5442–5460. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blasi A. Coagulopathy in liver disease: lack of an assessment tool. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:10062–10071. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i35.10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Violi F, Leo R, Vezza E, et al. Bleeding time in patients with cirrhosis: relation with degree of liver failure and clotting abnormalities. C.A.L.C. Group. Coagulation Abnormalities in Cirrhosis Study Group. J Hepatol. 1994;20:531–536. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80501-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tripodi A, Primignani M, Mannucci PM. Abnormalities of hemostasis and bleeding in chronic liver disease: the paradigm is challenged. Intern Emerg Med. 2010;5:7–12. doi: 10.1007/s11739-009-0302-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.James K, Bertoja E, O’Beirne J, Mallett S. Use of thromboelastography platelet mapping to monitor antithrombotic therapy in a patient with Budd-Chiari syndrome. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:38–41. doi: 10.1002/lt.21933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trotter JF, Brimhall B, Arjal R, Phillips C. Specific laboratory methodologies achieve higher model for endstage liver disease (MELD) scores for patients listed for liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:995–1000. doi: 10.1002/lt.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weeder PD, Porte RJ, Lisman T. Hemostasis in liver disease: implications of new concepts for perioperative management. Transfus Med Rev. 2014;28:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Polli F, Gattinoni L. Balancing volume resuscitation and ascites management in cirrhosis. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2010;23:151–158. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32833724da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henriksen JH, Bendtsen F, Sørensen TI, Stadeager C, Ring-Larsen H. Reduced central blood volume in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:1506–1513. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90396-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schrier RW, Arroyo V, Bernardi M, et al. Peripheral arterial vasodilation hypothesis: a proposal for the initiation of renal sodium and water retention in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1988;8:1151–1157. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aggarwal A, Ong JP, Younossi ZM, et al. Predictors of mortality and resource utilization in cirrhotic patients admitted to the medical ICU. Chest. 2001;119:1489–1497. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.5.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]