Abstract

Purpose

To assess the utility of morphologic and quantitative CT features in differentiating abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE) from other masses of the abdominal wall.

Methods

Retrospective IRB-approved study of 105 consecutive women from 2 institutions who underwent CT and biopsy/resection of abdominal wall masses. CTs were independently reviewed by 2 radiologists blinded to final histopathologic diagnoses. Associations between CT features and pathology were tested using Fisher's Exact Test. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values were calculated. P-values were adjusted for multiple variable testing.

Results

24.8% (26/105) of patients had histologically proven abdominal wall endometriosis. The other most common diagnoses included adenocarcinoma NOS (21%; 22/105), desmoid (14.3%; 15/105) and leiomyosarcoma (8.6%; 9/105). CT features significantly associated with endometriosis for both readers were location below the umbilicus (p=0.0188), homogeneous density (p=0.0188), and presence of linear infiltration irradiating peripherally from a central soft tissue nodule (i.e. “gorgon” sign) (p<0.0001). The highest combined sensitivity (0.69, 95% CI: 0.48-0.86) and specificity (0.97, 95% CI: 0.91-1.00) for both readers occurred for patients having all three of these features present. Border type (p=0.0199) was only significant for R2, peritoneal extension (p=0.0188) was only significantly for R1 and the remainder of features were insignificant (p=0.06-60). There was overlap in Hounsfield attenuation on non-contrast CT (n=26) between AWE (median: 45HU, range: 39-54) and other abdominal wall masses (median: 38.5HU, range: 15-58).

Conclusion

CT features are helpful in differentiating AWE from other abdominal wall soft tissue masses. Such differentiation may assist decisions regarding possible biopsy and treatment planning.

Introduction

Abdominal wall masses have a wide differential diagnosis, which includes endometriosis and other neoplastic and inflammatory etiologies. Abdominal wall endometriosis is commonly associated with scars related to Cesarean section, hysterectomy and other uterine surgery. However, in a substantial minority of cases, AWE does not arise in association with abdominal scarring or in the context of prior surgery (1, 2). The condition may be detected incidentally on imaging or it may come to medical attention because of chronic abdominal or pelvic pain. As with the pelvic variety, malignant transformation is a rare but recognized complication (3). Although the diagnosis may at times be made based on clinical presentation, in many scenarios, clinical manifestations of AWE are nonspecific, and patients may complain only of vague abdominal pain, a tender mass, or they may be asymptomatic (3). Moreover, symptoms may not occur until years after uterine surgery (reported cases range from 6 months to 20 years), and as such may not be recognized as being related to prior surgical treatment (4).

As CT scan is often part of the evaluation of patients with abdominal pain, awareness of potential differences and similarities in cross-sectional imaging features between AWE and other abdominal wall masses is important. Furthermore, an abdominal wall soft tissue mass may be detected incidentally in an asymptomatic patient being evaluated with CT for an unrelated condition.

The literature regarding the imaging features of AWE is scarce, and discriminating imaging features are not well-defined. While some have studied sonographic features of AWE (5,6,7,8,9,10), the existing literature on CT is limited to case reports, with CT features often described as nonspecific with variable attenuation and enhancement characteristics (4,5,7,8,11). There have been no studies evaluating the role of CT in distinguishing AWE from other abdominal wall masses. Thus, the purpose of this study is to assess the utility of morphologic and quantitative CT features in differentiating abdominal wall endometriosis from other masses of the abdominal wall.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

This retrospective study was HIPAA-compliant and IRB approved with a waiver of the requirement for written informed consent. Pathology databases of two institutions were searched for the terms “abdominal wall mass” and “pelvic wall mass” in female patients between ages 18 and 55, from January 2000 through April 2014. Initially, 323 cases were identified. Then, only cases with CT studies performed within 12 months prior to histopathologic evaluation were considered, yielding a cohort of 111 cases. Of these, 5 cases were excluded because the biopsied mass was along the pelvic sidewall and 1 case was excluded because the biopsied mass was in the left upper quadrant and not within the anterior abdominal or pelvic wall soft tissues. The final cohort included 105 patients with median age 41 years (range: 21-55 years); 24.8% (26/105) had histologically proven endometriosis.

Histopathologic criteria for the diagnosis of endometriosis in our series included the presence of benign-appearing endometrial glands and stroma with evidence of fresh or remote hemorrhage. Occasional cases lacked either obvious endometrial stroma or hemorrhage, but not both. When endometrial stroma was not apparent, a diagnosis of endometriosis required benign-appearing endometrioid glands and architectural features that were characteristic of endometriosis. So-called “stromal endometriosis,” a lesion containing endometrial stroma, but no glands, was not encountered in this cohort.

Image acquisition and analysis

CT scans were performed on 16 or 64 detector row GE helical scanners (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). Images were reconstructed at 2.5-mm or 5-mm intervals. Iodinated intravenous contrast material (120 – 150 cm3 Omnipaque-300) was administered to 76 of 105 patients (72.4%).

Two fellowship-trained radiologists (HAV and GY with 4 and 5 years of experience, respectively) blinded to the final histopathologic diagnoses independently reviewed all CT scans. They assessed each study for the following qualitative CT features: border type (irregular, lobulated, or smooth), presence of calcifications, intramuscular versus subcutaneous fat location, homogeneous versus heterogeneous density, association with a scar, multiplicity, location above or below the umbilicus, presence of coexisting intraperitoneal disease and presence of intraperitoneal extension. The presence of linear infiltration irradiating peripherally from a central soft tissue nodule, which we refer to as the “gorgon sign”, was also recorded (Figure 1). A mass was considered to have subcutaneous fat location if greater than 50% of the mass extended into the subcutaneous soft tissues. Similarly, a mass was considered to have intraperitoneal extension if greater than 50% of the lesion bulged into the peritoneal cavity. Both readers measured mass densities on all non-contrast cases by placing an ROI in the center of the mass, encompassing at least 50% of the lesion. Seventy-six studies were performed following intravenous contrast administration only, precluding evaluation of pre-contrast density.

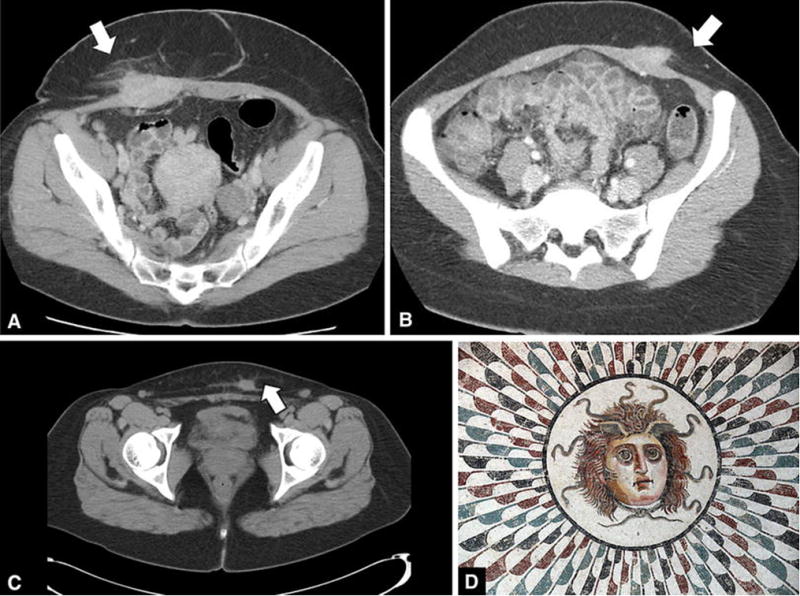

Figure 1.

Axial CT images of 3 different cases of AWE is our series (a,b,c), each demonstrating the “gorgon” sign (arrows). This finding may be explained by the similarity between AWE and the deep penetrating type of endometriosis, with a predominance of histiocytic infiltration and fibrosis due to chronic hemorrhage. A cartoon of the mythological figure “gorgon” is depicted © Ad Meskens/Wikimedia Commons (d).

Statistical analysis

Clinical, pathologic and imaging characteristics were summarized using medians and ranges for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables (Table 1). Inter-reader agreement for CT features was assessed with Cohen's simple Kappa statistic with 95% confidence intervals and percentage agreement.

Table 1. Patient characteristics (n=105).

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age at CT (years) | Median (range) | 40.8 (21-55.2) |

| Histology | Endometriosis | 26 (24.8) |

| Adenocarcinoma NOS | 22 (21) | |

| Desmoid | 15 (14.3) | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 9 (8.6) | |

| Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma | 5 (4.8) | |

| Lymphoma | 3 (2.9) | |

| Lipoma | 3 (2.9) | |

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | 3 (2.9) | |

| Blastoma | 2 (1.9) | |

| Inflammatory | 2 (1.9) | |

| Fibromatosis | 2 (1.9) | |

| Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor | 2 (1.9) | |

| Synovial Sarcoma | 2 (1.9) | |

| Endometrioid Carcinoma | 1 (1) | |

| Epithelioid Sarcoma | 1 (1) | |

| Fibrosarcoma | 1 (1) | |

| Hemangiopericytoma | 1 (1) | |

| Borderline Papillary Serous Cystadenoma | 1 (1) | |

| Sex Cord Stromal Tumor | 1 (1) | |

| Small Cell Carcinoma | 1 (1) | |

| Spindle Cell Melanoma | 1 (1) | |

| Adenosquamous Carcinoma | 1 (1) |

Associations between CT features and endometriosis were tested using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables (Table 2). P-values were adjusted for multiple testing using the false discovery rate approach and values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The variables significant for both readers in the above analysis were combined into a feature scoring system (Table 3). Scores could range from at least 1 feature present to having all 3 features present. Diagnostic accuracy, including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated for each of these levels along with exact 95% CI. We then noted the differences between each of these levels.

Table 2. Univariate associations between imaging features and endometriosis.

| Endometriosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT Feature | Reader | No | Yes | p-value | |

| Coexisting Intraperitoneal Disease | R1 | No | 62 (78.5) | 25 (96.2) | 0.06 |

| Yes | 17 (21.5) | 1 (3.8) | |||

| R2 | No | 61 (77.2) | 25 (96.2) | 0.06 | |

| Yes | 18 (22.8) | 1 (3.8) | |||

| Border Type | R1 | Irregular | 17 (21.5) | 12 (46.2) | 0.06 |

| Lobulated | 13 (16.5) | 1 (3.8) | |||

| Smooth | 49 (62) | 13 (50) | |||

| R2 | Irregular | 22 (27.8) | 16 (61.5) | .0199 | |

| Lobulated | 12 (15.2) | 1 (3.8) | |||

| Smooth | 45 (57) | 9 (34.6) | |||

| Calcifications | R1 | No | 72 (91.1) | 26 (100) | 0.22 |

| Yes | 7 (8.9) | 0 (0) | |||

| R2 | No | 72 (91.1) | 26 (100) | 0.22 | |

| Yes | 7 (8.9) | 0 (0) | |||

| Gorgon Sign | R1 | No | 76 (96.2) | 7 (26.9) | <.0001 |

| Yes | 3 (3.8) | 19 (73.1) | |||

| R2 | No | 77 (97.5) | 7 (26.9) | <.0001 | |

| Yes | 2 (2.5) | 19 (73.1) | |||

| Heterogeneity | R1 | Heterogeneous | 33 (41.8) | 3 (11.5) | .0188 |

| Homogeneous | 46 (58.2) | 23 (88.5) | |||

| R2 | Heterogeneous | 34 (43) | 3 (11.5) | .0188 | |

| Homogeneous | 45 (57) | 23 (88.5) | |||

| Location | R1 | Intramuscular | 38 (48.1) | 6 (23.1) | 0.09 |

| Subcutaneous | 17 (21.5) | 7 (26.9) | |||

| Both | 24 (30.4) | 13 (50) | |||

| R2 | Intramuscular | 40 (50.6) | 6 (23.1) | 0.06 | |

| Subcutaneous | 17 (21.5) | 7 (26.9) | |||

| Both | 22 (27.8) | 13 (50) | |||

| Peritoneal Extension | R1 | No | 51 (64.6) | 24 (92.3) | .0188 |

| Yes | 28 (35.4) | 2 (7.7) | |||

| R2 | No | 61 (77.2) | 25 (96.2) | 0.06 | |

| Yes | 18 (22.8) | 1 (3.8) | |||

| Association with Scar | R1 | No | 61 (77.2) | 17 (65.4) | 0.33 |

| Yes | 18 (22.8) | 9 (34.6) | |||

| R2 | No | 61 (77.2) | 16 (61.5) | 0.17 | |

| Yes | 18 (22.8) | 10 (38.5) | |||

| Additional Similar Masses | R1 | No | 64 (81) | 19 (73.1) | 0.43 |

| Yes | 15 (19) | 7 (26.9) | |||

| R2 | No | 62 (78.5) | 19 (73.1) | 0.60 | |

| Yes | 17 (21.5) | 7 (26.9) | |||

| Above or Below Umbilicus | R1 | Above | 23 (29.1) | 1 (3.8) | .0188 |

| Below | 56 (70.9) | 25 (96.2) | |||

| R2 | Above | 24 (30.4) | 1 (3.8) | .0188 | |

| Below | 55 (69.6) | 25 (96.2) | |||

Table 3. Diagnostic accuracy of combined features.

| At least | Reader | Sensitivity [95% CI; n] | Specificity [95% CI; n] | PPV [95% CI; n] | NPV [95% CI; n] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 feature present | R1 | 0.96 [0.8-1;25/26] | 0.08 [0.03-0.16;6/79] | 0.26 [0.17-0.35;25/98] | 0.86 [0.42-1;6/7] |

| R2 | 0.96 [0.8-1;25/26] | 0.1 [0.04-0.19;8/79] | 0.26 [0.18-0.36;25/96] | 0.89 [0.52-1;8/9] | |

| 2 features present | R1 | 0.92 [0.75-0.99;24/26] | 0.62 [0.5-0.73;49/79] | 0.44 [0.31-0.59;24/54] | 0.96 [0.87-1;49/51] |

| R2 | 0.92 [0.75-0.99;24/26] | 0.63 [0.52-0.74;50/79] | 0.45 [0.32-0.6;24/53] | 0.96 [0.87-1;50/52] | |

| 3 features present | R1 | 0.69 [0.48-0.86;18/26] | 0.97 [0.91-1;77/79] | 0.9 [0.68-0.99;18/20] | 0.91 [0.82-0.96;77/85] |

| R2 | 0.69 [0.48-0.86;18/26] | 0.97 [0.91-1;77/79] | 0.9 [0.68-0.99;18/20] | 0.91 [0.82-0.96;77/85] |

For patients with non-contrast CTs (N=26), the densities in Hounsfield units for patients with and without endometriosis were assessed with descriptive statistics and box plots. Due to the small patient sample, formal hypothesis tests were not conducted. Lesions with obvious calcifications and gross fat were excluded from this part of the analysis. To assess the effect of contrast on the appearance of mass heterogeneity in patients both with and without endometriosis, a logistic regression was performed with an interaction term for contrast and heterogeneity; endometriosis was the independent outcome for both readers 1 and 2.

Results

Patient and Lesion Characteristics

The final cohort included 105 patients with median age 41 years (range 21 – 55 years); 24.8% (26/105) showed histologically proven endometriosis. Of non-endometriosis diagnoses, there were 28 patients with adenocarcinoma (21%), 15 with desmoid (14.3%), 9 with leiomyosarcoma (8.6%), 3 with lymphoma (2.9%), 3 with lipoma (2.9%), 3 with squamous cell carcinoma (2.9%), 2 with blastoma (1.9%), 2 with abscess and/or fat necrosis (1.9%), 2 with fibromatosis (1.9%), 2 with gastrointestinal stromal tumor (1.9%) and 2 with synovial sarcoma (1.9%). Other diagnoses constituted 1% each of the total number of cases and are listed in Table 1. Of the 28 adenocarcinomas, 5 were clear cell subtype and 1 was endometrioid subtype. Both entities have a known association with endometriosis (12).

Inter-reader Agreement

Inter-reader agreement ranged from substantial for border type (85.7%, k=0.75, 95%CI: 0.64 - 0.87) and peritoneal extension (89.5%, k=0.71, 95% CI: 0.56 – 0.87) to almost perfect on calcifications (98.1%, k=0.85, 95% CI: 0.64 – 1.00), gorgon sign (99%, k=0.97, 95% CI: 0.91 – 1.00), mass location (93.3%, k=0.90, 95% CI: 0.82 – 0.97), mass heterogeneity (95.2%, k=0.90, 95% CI: 0.81 – 0.98), association with scar (95.2%, k=0.88, 95% CI: 0.77 – 0.98), additional similar masses (98.1%, k=0.94, 95% CI: 0.87 – 1.00), position above or below the umbilicus (99%, k=0.97, 95% CI: 0.92 – 1.00), and coexisting intraperitoneal disease (99%, k=0.97, 95% CI: 0.90 – 1.00).

Univariate Analysis

For both readers, gorgon sign (p<0.0001 for both), homogeneous density (p=0.0188 for both) and location above or below umbilicus (p=0.0188 for both) were significantly associated with endometriosis. A higher proportion of patients with AWE had gorgon sign compared with patients having other diagnoses (R1: 73.1% vs. 3.8% and R2: 73.1% vs. 2.5%). Additionally, endometriosis patients had a higher proportion of homogeneous density masses (R1: 88.5% vs. 58.2% and R2: 88.5% vs. 57%), and masses located below the umbilicus compared with other patients (R1: 96.2% vs. 70.9% and R2: 96.2% vs. 69.6%). Border type was significant for reader 2 (p=0.0199), but not for reader 1 (p=0.06), and peritoneal extension was significant for reader 1 (p=0.0188) but not for reader 2 (p=0.06). No other features, including calcifications, mass location, coexisting intraperitoneal disease or additional similar masses were found to be significant (p=0.06-60) (Table 2). No relationship was found between the use of IV contrast and heterogeneity in predicting endometriosis (p=0.96-0.97). Patients with IV contrast (76/105 patients) did not display different profiles of heterogeneity.

Combined Feature Diagnosis Accuracy

Patients with at least 1 feature present had the highest sensitivity in diagnosing AWE (0.96, 95% CI: 0.80-1.00 for both), but the lowest specificity (0.08, 95% I: 0.03-0.16 for R1 and 0.10, 95% CI: 0.04-0.19 for R2). Patients with at least 2 features present also had a high sensitivity in assessing AWE (0.92, 95% CI: 0.75-0.99 for both), but moderate specificity (0.62, 95% CI: 0.50-0.73 for R1 and 0.63, 95% CI: 0.52-0.74 for R2). The highest combined sensitivity (0.69, 95% CI: 0.48-0.86 for both) and specificity (0.97, 95% CI: 0.91-1.00 for both) occurred for patients having all three features present, though sensitivity in predicting endometriosis declined with the more stringent requirement (Table 3).

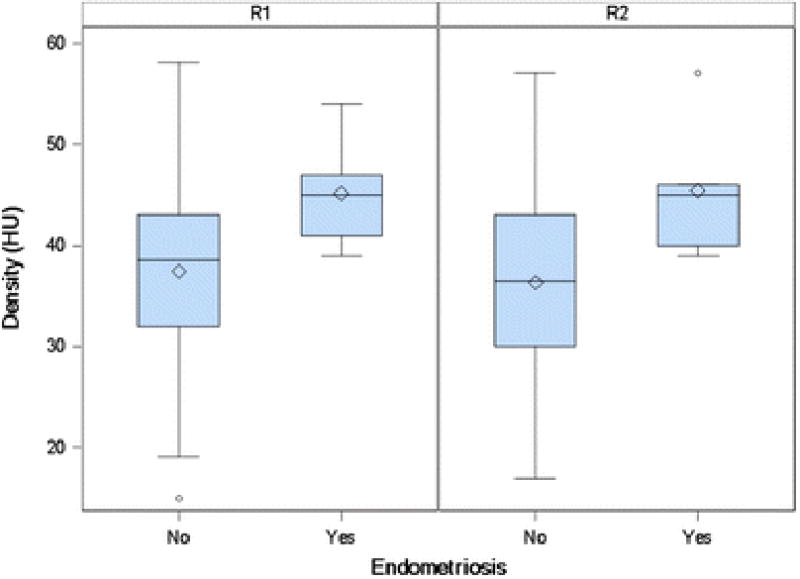

Mass Density

Twenty-nine patients had non-contrast CT scans. Three of the 29 had extremely skewed densities (below -100 or above 100) and excluded from further descriptive statistics. None of these three patients had AWE. In patients with endometriosis (N=5), the median density was 45 HU (range 39-54 HU), while for patients with other diagnoses, the median density was 38.5 HU (range 15 – 58 HU) (Table 4 and Fig. 2).

Table 4. Density descriptive statistics for patients with non-contrast studies (N=26, N=5(Endometriosis)).

| Endometriosis | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||||||

| Mean | (95% | CI) | Median | (Min- Max) | Mean | (95% CI) | Median | (Min- Max) | ||

| Density (HU) | R1 | 37.4 | (32.9 - | 41.9) | 38.5 | (15.0 - 58.0) | 45.2 | (37.9 - 52.5) | 45.0 | (39.0 - 54.0) |

| R2 | 36.4 | (32.0 - | 40.7) | 36.5 | (17.0 - 57.0) | 45.4 | (36.5 - 54.3) | 45.0 | (39.0 - 57.0) | |

Figure 2. Boxplot of Density (N=26).

Discussion

This study compared a spectrum of CT features in cases of AWE and of other masses of the abdominal wall, all with histopathologic verification. Significant differences were observed; the presence of “gorgon” sign, mass homogeneity and location below the umbilicus were significantly associated with endometriosis. The presence of all three features provided the highest combined sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis.

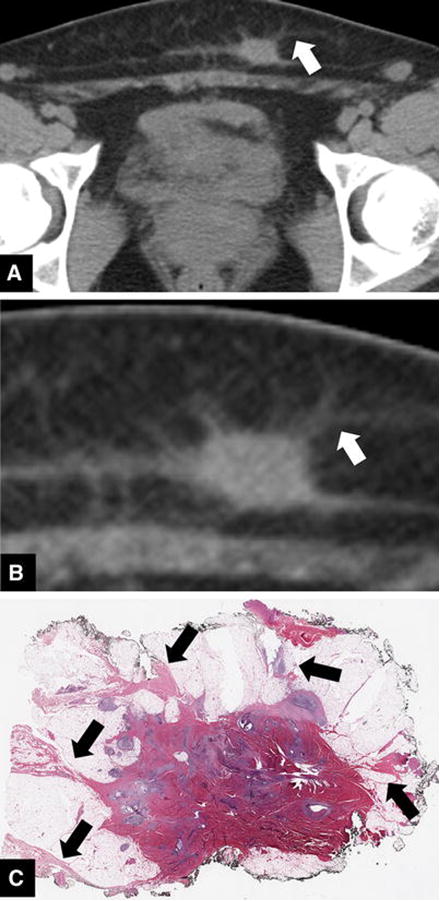

We defined the “gorgon” sign as the presence of linear infiltration radiating peripherally to the adjacent subcutaneous fat from a central soft tissue nodule (Fig. 1). Upon histopathologic evaluation, cases with the gorgon sign exhibited an appearance similar to that of deep pelvic endometriosis, in which there is a predominance of histiocytic infiltration and fibrosis due to chronic hemorrhage, and few glands (Fig. 3). This appearance is in contrast with the ovarian form of endometriosis in which there is classically a predominance of ectopic endometrial glands and/or an endometriotic cyst, with fibrosis not a dominating feature.

Figure 3.

42-year-old woman with AWE. Axial CT image (a) and a coned down image of the same lesion (b) demonstrating linear perilesional infiltration (white arrows). Photomicrograph at low magnification (c) demonstrates linear fibrosis extending from the lesion, corresponding with the finding on CT (black arrows). Similar to the deep penetrating type of endometriosis, this lesion demonstrates a predominance of fibrosis due to chronic hemorrhage, with few glands.

The literature regarding imaging features of AWE is scarce, with many authors concluding that the usefulness of imaging is limited to determining the location and extent of involvement of the lesion with respect to the surrounding tissue. Interestingly, the few studies that consider the sonographic features of abdominal wall endometriosis have described specific features, including solid lesions with ill-defined blurred outer borders and the presence of a hyperechoic ring. The latter correspond to adipose tissue that has become edematous and is filled with cells of inflammatory origin (9, 10). Our findings are consistent with these results, as the “gorgon” sign may be a CT correlate to the hyperechoic rim seen on ultrasound.

Awareness of the discriminating imaging features that we describe may impact clinical management and the workup of abdominal wall masses. An understanding of the significance of these features could potentially facilitate appropriate diagnosis at the time of initial image interpretation. This may in turn assist in patient counseling and in selection of optimal management strategies (13). While hormonal suppression or surgical resection will often be needed, especially for patients symptomatic for pain at the abdominal wall site, this valuable radiographic information could provide opportunity for a non-operative approach. In a patient with history of primary malignancy, tissue sampling may be deemed appropriate regardless of CT appearance. However, if imaging features are suggestive of AWE, this information may affect the radicality of dissection and the need for complex abdominal wall reconstruction.

Treatment options for AWE have evolved. The hallmark of endometriosis management is hormonal suppression and surgical resection, however treatments with percutaneous cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation have been reported (14, 15). There is thus substantive impact on patient counseling and treatment planning as a result of accurate initial interpretation of imaging.

Our study had several limitations. First, it was retrospective and had a small sample size (26 cases of endometriosis among the 105 cases evaluated). Second, only masses that were biopsied were included in the study, introducing a verification bias in the sample. Although this provided the most rigorous imaging to pathology correlation possible, it must be acknowledged that in standard practice not all abdominal wall masses require biopsy for clinical management, especially if longstanding and asymptomatic. Third, due to lack of pre and post-contrast images in most cases, we were not able to assess enhancement characteristics. In our assessment of lesion heterogeneity, we did not differentiate between those patients who were given intravenous contrast and those who were not. However, a sensitivity analysis revealed no relationship between contrast and heterogeneity in predicting endometriosis (p=0.96-0.97). Patients with contrast did not display different profiles of heterogeneity; however, given the limited sample size of non-contrast patients, this analysis should be repeated with a larger sample of patients with non-contrast CT.

In conclusion, our study showed significant differences between CT features of abdominal wall endometriosis and those of other abdominal wall masses. Increased awareness of this possible diagnosis and improved understanding of its discriminating imaging features may be valuable for assisting clinical management.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards: This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748; the authors declare no conflicts of interest; no human or animal subjects were involved.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Horton JD, Dezee KJ, Ahnfeldt EP, Wagner M. Abdominal wall endometriosis: a surgeon's perspective and review of 445 cases. Am J Surg. 2008;196(2):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granese R, Cucinella G, Barresi V, Navarra G, Candiani M, Triolo O. Isolated endometriosis on the rectus abdominis muscle in women without a history of abdominal surgery: a rare and intriguing finding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16(6):798–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matter M, Schneider N, McKee T. Cystadenocarcinoma of the abdominal wall following caesarean section: case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91(2):438–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gidwaney R, Badler RL, Yam BL, et al. Endometriosis of abdominal and pelvic wall scars: multimodality imaging findings, pathologic correlation, and radiologic mimics. Radiographics. 2012;32:2031–2043. doi: 10.1148/rg.327125024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hensen JH, Van Breda Vriesman AC, Puvlaert J. Abdominal wall endometriosis: clinical presentation and imaging features with emphasis on sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:616–620. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu Z, Al-Beiti MA, Tang L, Liu X, Lu X. Clinical characteristic analysis of 32 patients with abdominal incision endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28:742–745. doi: 10.1080/01443610802463744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busard MP, Mijatovic V, van Kuijk C, Hompes PG, van Waesberghe JH. Appearance of abdominal wall endometriosis on MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:1267–1276. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1658-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn SE, Park SJ, Moon SK, Lee DH, Lim JW. Sonography of abdominal wall masses and masslike lesions: correlation with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35(1):189–208. doi: 10.7863/ultra.15.03027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francica G. Reliable clinical and sonographic findings in the diagnosis of abdominal wall endometriosis near cesarean section scar. World Journal of Radiology. 2012;4(4):135–140. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v4.i4.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savelli L, Manuzzi L, Di Donato N, et al. Endometriosis of the abdominal wall: ultrasonographic and Doppler characteristics. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:336–340. doi: 10.1002/uog.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coley BD, Casola G. Incisional endometrioma involving the rectus abdominis muscle and subcutaneous tissues: CT appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160(3):549–550. doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.3.8430549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giudice LC, Swiersz LM, Burney RO. Endometriosis. In: Jameson JL, De Groot LJ, editors. Endocrinology. 6th. New York: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 2356–2370. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aytac HO, Aytac PC, Parlakgumus HA. Scar endometriosis is a gynecological complication that general surgeons have to deal with. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2015;42(3):292–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornelius F, Petipierre F, Lasserre E, et al. Percutaneous cryoablation of symptomatic abdominal scar endometrioma: initial reports. Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology. 2014;37(6):1575. doi: 10.1007/s00270-014-0843-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrafiello G, Fontana F, Pellegrino C, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of abdominal wall endometrioma. Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology. 2009;32(6):1300. doi: 10.1007/s00270-008-9500-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]