Abstract

Objective

To compare prenatal care providers’ perceived self-efficacy in starting discussions about gestational weight gain with pregnant women under a variety of conditions of gradated difficulty, when weight gain has been in excess of current guidelines.

Design

A 42-item online questionnaire related to the known barriers to and facilitators of having discussions about gestational weight gain.

Setting

Canada.

Participants

Prenatal care providers were contacted through the Family Medicine Maternity Care list server of the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

Main outcome measures

The 42 items were clustered into categories representing patient factors, interpersonal factors, and system factors. Participants scored their self-efficacy on a scale from 0 (“cannot do at all”) to 5 (“moderately certain can do”) to 10 (“highly certain can do”). The significance level was set at α = .05.

Results

Overall, clinicians rated their self-efficacy to be high, ranging from a low mean (SD) score of 5.14 (3.24) if the clinic was running late, to a high mean score of 8.97 (1.34) if the clinician could externalize the reason for undertaking the discussion. There were significant differences in self-efficacy scores within categories depending on the degree of difficulty proposed by the items in those categories.

Conclusion

The results were inconsistent with previous studies that have demonstrated that prenatal care providers do not frequently raise the subject of excess gestational weight gain. On the one hand providers rate their self-efficacy in having these discussions to be high, but on the other hand they do not undertake the behaviour, at least according to their patients. Future research should explore this discrepancy with a view to informing interventions to help providers and patients in their efforts to address excess gestational weight gain, which is increasingly an important contributor to the obesity epidemic.

Résumé

Objectif

Comparer la perception qu’ont les médecins offrant des soins prénatals de leur propre efficacité à amorcer des discussions entourant le gain pondéral gestationnel avec les femmes enceintes, dans diverses circonstances où la difficulté est graduellement plus élevée, lorsque le gain pondéral est supérieur aux lignes directrices actuelles.

Conception

Un questionnaire en ligne en 42 points concernant les éléments qui entravent ou facilitent des discussions entourant le gain pondéral gestationnel.

Contexte

Canada.

Participants

Des médecins offrant des soins prénatals ont été rejoints à partir du serveur de liste des Soins de maternité en médecine familiale du Collège des médecins de famille du Canada.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

Les 42 éléments ont été regroupés en catégories représentant les facteurs associés aux patientes, les facteurs interpersonnels et les facteurs systémiques. Les participants évaluaient leur propre efficacité sur une échelle allant de 0 (« ne peut pas en discuter du tout ») à 5 (« peut en discuter modérément ») et à 10 (« peut certainement en discuter »). Le seuil de signification a été fixé à α = ,05.

Résultats

Dans l’ensemble, les cliniciens ont évalué leur propre efficacité comme étant élevée, allant d’une basse cote moyenne (ET) de 5,14 (3,24) si la clinique accusait du retard dans les rendez-vous, à une cote élevée moyenne de 8,97 (1.34) si le clinicien pouvait exprimer la raison d’entamer la discussion. Il y avait des différences significatives dans les cotes d’évaluation de l’efficacité au sein des catégories, selon le degré de difficulté proposé par les scénarios dans ces catégories.

Conclusion

Ces résultats ne concordent pas avec ceux d’études antérieures ayant démontré que les médecins qui offrent des soins prénatals n’abordent pas souvent le sujet d’un gain pondéral gestationnel excessif. D’une part, les médecins évaluent leur efficacité à avoir ces discussions comme étant élevée, alors que d’autre part, ils n’adoptent pas ce comportement, du moins selon leurs patientes. D’autres études de recherche devraient explorer cette divergence dans le but d’éclairer les interventions nécessaires pour aider les médecins et les patientes dans leurs efforts visant à éviter le gain pondéral gestationnel excessif, qui contribue grandement et de plus en plus à l’épidémie d’obésité.

Excess weight gain in pregnancy is a risk factor for a number of adverse outcomes for mothers and their offspring, including downstream childhood obesity.1–3 Guidelines exist pertaining to how much weekly and total weight should be gained based on women’s prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) category.4,5 In Canada, more than 50% of women gain weight in excess of these guidelines.6–8

A number of factors influence the guideline concordance of gestational weight gain, including advice from a prenatal care provider.9–11 Although research shows that patients want their primary care clinicians to address gestational weight gain,12 such discussions tend to occur infrequently,11–18 especially as perceived by patients. Clinicians consider these conversations to be of a sensitive nature, and they fear offending, angering, or embarrassing their patients by raising the topic.13,19–23 They have been shown to be more likely to provide advice about gestational weight gain when women are nulliparous, have a higher education, or have a higher socioeconomic status (SES).9,11,24 They are also more likely to provide advice if they can externalize the discussion toward the health of the baby19 or toward weight-related comorbidities.11 Prepregnancy BMI does not appear to influence the provision of advice, and there is controversy about the effect of maternal age.9,11,24,25

Anecdotal evidence suggests that clinicians perceive few barriers to briefly addressing gestational weight gain when the gain has been congruent with the guidelines. When the weight gain has been incongruent with the guidelines, they perceive less discomfort in raising the issue in the context of inadequate compared with excess weight gain. As most women gain weight in excess of the guidelines, this is potentially a concern.

Previous studies have shown that clinician-perceived barriers to initiating discussions about gestational weight gain include a lack of time15,26,27 and a lack of confidence.28,29 From a theoretical perspective, confidence is related to perceived self-efficacy. This latter construct refers to “judgments of how well one can execute courses of action required to deal with prospective situations.”30 According to Albert Bandura, a psychologist renowned for his contribution to this field, such judgment is mediated by 4 sources of information,31 perhaps the most important one being performance outcomes, or mastery experiences, which refers to the influence of positive or negative past experiences on one’s ability to perform a task. Bandura further states that there is no “all-purpose” measure of self-efficacy32—a given individual might have high self-efficacy in some domains and low self-efficacy in others, and variations within a domain occur with diverse levels of difficulty within that domain.

The aim of this study was to compare clinicians’ perceived self-efficacy in initiating discussions about gestational weight gain with pregnant women under a variety of conditions and in the context of weight gain in excess of current guidelines.

METHODS

Approval for this study was obtained from the Nova Scotia Health Authority Research Ethics Board in Halifax, NS. Survey items that relate to the known barriers to and facilitators of having discussions about gestational weight gain were created consistent with Bandura’s approach. Before data collection, these items were proofread and examined for face validity by the author’s workplace colleagues who provide regular prenatal care. The final list of 42 items was entered into a Web-based survey system. Potential participants (N = 91) were reached via e-mail through contact information in the Family Medicine Maternity Care list server of the College of Family Physicians of Canada. Completion of the questionnaire constituted informed consent. Participants’ professions were purposefully not explored in order to reduce the chance of bias owing to the rumoured, albeit unsubstantiated, existence of “turf wars.”33–35 Following a period of 8 weeks, the data were extracted from the survey software into SPSS, version 21.

The 42 items represented various conditions and were clustered into a number of categories. These categories included patient factors such as patient prepregnancy BMI, age, parity, education, SES, and presence of weight-related comorbidities; interpersonal factors such as clinician familiarity with the patient, understanding of the patient’s culture, perceived quality of the patient-clinician relationship, comparison of the patient’s prepregnancy BMI to the clinician’s own BMI, and whether the patient attended the prenatal visit alone or accompanied by someone; and clinic factors such as the degree to which the clinic was running on time and time allotted for the prenatal visit. For each item, participants were asked to rate their self-efficacy in starting a discussion about gestational weight gain with a patient who had gained more than the recommended amount on a scale from 0 (“cannot do at all”) to 5 (“moderately certain can do”) to 10 (“highly certain can do”). The significance level was set at α = .05. As the variables were not normally distributed (ie, they were skewed to the left) and were not independent, nonparametric tests (ie, Friedman tests and Wilcoxon signed rank tests) were used to compare the mean self-efficacy scores within the categories and between items.

RESULTS

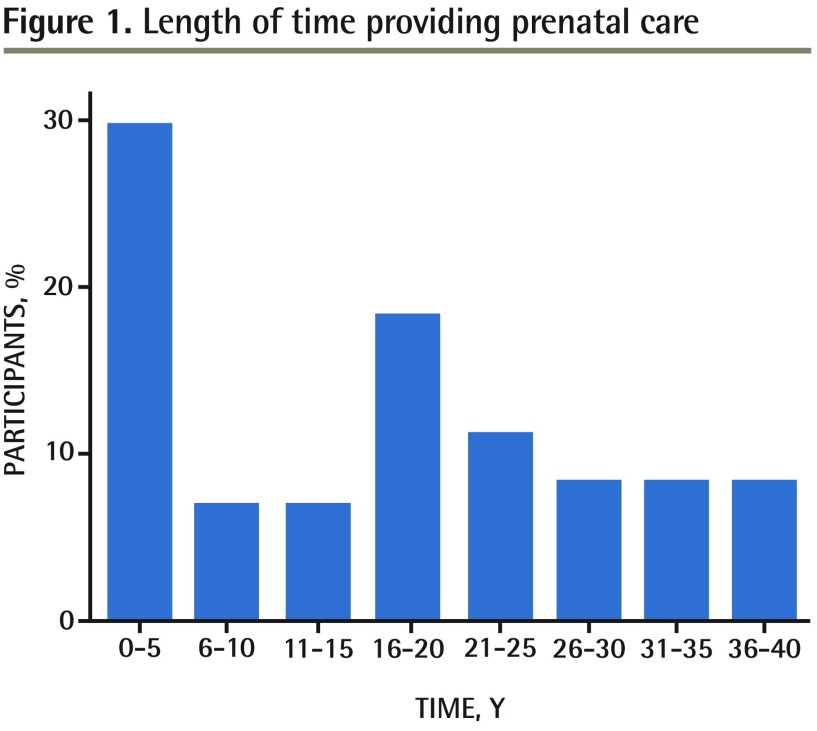

Seventy-one clinicians completed the questionnaire, corresponding to a 78% response rate. Most respondents were female (94%); as a group, respondents had been providing prenatal care for a range of years, with approximately two-thirds of respondents reporting having provided prenatal care from 0 to 20 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Length of time providing prenatal care

Self-efficacy was highest (mean [SD] 8.97 [1.34]) if the clinician could externalize the reason for undertaking the discussion, ie, if the patient had existing weight-related comorbidities (Table 1). Conversely, self-efficacy was lowest (mean [SD] 5.14 [3.24]) with system issues, ie, if the clinic was running 60 minutes late.

Table 1.

List of items in each category and mean self-efficacy scores: Self-efficacy was scored on a scale of 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating greater self-efficacy.

| CATEGORY | ITEMS | MEAN (SD) SELF-EFFICACY SCORE |

|---|---|---|

| Patient’s prepregnancy BMI | Her prepregnancy BMI was in the underweight range | 8.31 (2.12) |

| Her prepregnancy BMI was in the normal range | 8.53 (1.89) | |

| Her prepregnancy BMI was in the overweight range | 8.35 (1.91) | |

| Her prepregnancy BMI was in the obese range | 8.48 (1.94) | |

| Patient’s age | She is a teenager | 8.20 (2.14) |

| She is a young adult | 8.44 (2.02) | |

| She is approaching middle age | 8.66 (1.60) | |

| Patient’s parity | It is her first pregnancy | 8.66 (1.87) |

| She has had ≥ 1 previous pregnancies | 8.28 (2.14) | |

| Patient’s education | Her education ended in high school | 8.42 (2.09) |

| She obtained postsecondary education | 8.63 (1.69) | |

| She has a postgraduate or professional degree | 8.46 (1.82) | |

| Patient’s SES | She is of low SES | 8.17 (2.28) |

| She is of middle SES | 8.46 (1.98) | |

| She is of high SES | 8.69 (1.82) | |

| Comorbidities | She has 1 weight-related comorbidity | 8.90 (1.35) |

| She has > 1 weight-related comorbidity | 8.97 (1.34) | |

| Familiarity with the patient | I know her well | 8.56 (1.87) |

| I know her somewhat | 8.18 (2.00) | |

| I do not know her at all | 7.63 (2.56) | |

| Understanding of patient’s culture | I understand her cultural background | 8.82 (1.53) |

| I do not understand her cultural background | 6.89 (2.59) | |

| Perceived quality of the clinician-patient relationship | I believe the quality of my relationship with her to be above average | 8.92 (1.39) |

| I believe the quality of my relationship with her to be average | 8.33 (1.81) | |

| I believe the quality of my relationship with her to be below average | 6.58 (2.57) | |

| Attendance alone or accompanied | She attends the prenatal visit by herself | 8.83 (1.46) |

| She attends the prenatal visit accompanied by someone with an underweight BMI | 7.66 (2.37) | |

| She attends the prenatal visit accompanied by someone with a normal BMI | 7.87 (2.21) | |

| She attends the prenatal visit accompanied by someone with an overweight BMI | 7.75 (2.29) | |

| She attends the prenatal visit accompanied by someone with an obese BMI | 7.73 (2.34) | |

| Comparison of patient’s prepregnancy BMI to clinician’s own BMI | Her prepregnancy BMI was a lot lower than mine | 8.57 (2.10) |

| Her prepregnancy BMI was lower than mine | 8.53 (2.06) | |

| Her prepregnancy BMI was the same as mine | 8.56 (2.04) | |

| Her prepregnancy BMI was higher than mine | 8.32 (2.22) | |

| Her prepregnancy BMI was a lot higher than mine | 8.24 (2.33) | |

| Degree to which the clinic is running on time | My clinic is running on time | 8.72 (1.75) |

| My clinic is running 30 min late | 6.21 (2.64) | |

| My clinic is running 60 min late | 5.14 (3.24) | |

| Time allotted for prenatal visit | I have 30 min for the visit | 8.80 (1.50) |

| I have 20 min for the visit | 7.86 (2.10) | |

| I have 15 min for the visit | 6.66 (2.59) | |

| I have 10 min for the visit | 5.70 (3.04) |

BMI—body mass index, SES—socioeconomic status.

There was no statistically significant difference in clinician self-efficacy based on the patient’s prepregnancy BMI or level of education. However, analyses for the other categories showed significant results. Friedman tests were used to compare items within categories containing more than 2 items (Table 2). Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used to compare pairs of items within the categories (Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of self-efficacy scores within categories using the Friedman test: Self-efficacy was scored on a scale of 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating greater self-efficacy.

| CATEGORY | ITEMS | MEAN (SD) SELF-EFFICACY SCORE | FRIEDMAN TEST |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient’s prepregnancy BMI | Underweight range | 8.31 (2.12) |

P = .572 |

| Normal range | 8.53 (1.89) | ||

| Overweight range | 8.35 (1.91) | ||

| Obese range | 8.48 (1.94) | ||

| Patient’s age | Teenager | 8.20 (2.14) |

P = .001 |

| Young adult | 8.44 (2.02) | ||

| Approaching middle age | 8.66 (1.60) | ||

| Patient’s education | High school | 8.42 (2.09) |

P = .067 |

| Postsecondary | 8.63 (1.69) | ||

| Postgraduate or professional degree | 8.46 (1.82) | ||

| Patient’s SES | Low SES | 8.17 (2.28) |

P < .001 |

| Middle SES | 8.46 (1.98) | ||

| High SES | 8.69 (1.82) | ||

| Familiarity with the patient | Familiar | 8.56 (1.87) |

P < .001 |

| Somewhat familiar | 8.18 (2.00) | ||

| Not at all familiar | 7.63 (2.56) | ||

| Perceived quality of the clinician-patient relationship | Above average | 8.92 (1.39) |

P < .001 |

| Average | 8.33 (1.81) | ||

| Below average | 6.58 (2.57) | ||

| Attendance alone or accompanied | Alone | 8.83 (1.46) |

P < .001 |

| Companion with underweight BMI | 7.66 (2.37) | ||

| Companion with normal BMI | 7.87 (2.21) | ||

| Companion with overweight BMI | 7.75 (2.29) | ||

| Companion with obese BMI | 7.73 (2.34) | ||

| Comparison of patient’s prepregnancy BMI to clinician’s own BMI | A lot lower | 8.57 (2.10) |

P = .034 |

| Lower | 8.53 (2.06) | ||

| The same | 8.56 (2.04) | ||

| Higher | 8.32 (2.22) | ||

| A lot higher | 8.24 (2.33) | ||

| Degree to which the clinic is running on time | On time | 8.72 (1.75) |

P < .001 |

| 30 min late | 6.21 (2.64) | ||

| 60 min late | 5.14 (3.24) | ||

| Time allotted for prenatal visit | 30 min | 8.80 (1.50) |

P < .001 |

| 20 min | 7.86 (2.10) | ||

| 15 min | 6.66 (2.59) | ||

| 10 min | 5.70 (3.04) |

BMI—body mass index, SES—socioeconomic status.

Table 3.

Comparison of pairs of items within categories using the Wilcoxon signed rank test

| CATEGORY | ITEMS COMPARED | Z STATISTIC | P VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient’s age | Teenager vs young adult | −3.305 | .001 |

| Teenager vs approaching middle age | −2.840 | .005 | |

| Young adult vs approaching middle age | −1.378 | .168 | |

| Patient’s parity | Nulliparous vs primiparous or multiparous | −2.741 | .006 |

| Patient’s SES | Low SES vs middle SES | −3.086 | .002 |

| Low SES vs high SES | −3.472 | .001 | |

| Middle SES vs high SES | −2.801 | .005 | |

| Comorbidities | 1 weight-related comorbidity vs > 1 weight-related comorbidity | −0.462 | .644 |

| Familiarity with the patient | Familiar vs somewhat familiar | −1.714 | .087 |

| Familiar vs not at all familiar | −2.554 | .011 | |

| Somewhat familiar vs not at all familiar | −3.082 | .002 | |

| Understanding of patient’s culture | Yes vs no | −5.618 | < .001 |

| Perceived quality of the clinician-patient relationship | Above average vs average | −4.030 | < .001 |

| Above average vs below average | −6.180 | < .001 | |

| Average vs below average | −6.017 | < .001 | |

| Attendance alone or accompanied | Alone vs companion with underweight BMI | −4.654 | < .001 |

| Alone vs companion with normal BMI | −4.075 | < .001 | |

| Alone vs companion with overweight BMI | −4.467 | < .001 | |

| Alone vs companion with obese BMI | −4.467 | < .001 | |

| Companion with underweight BMI vs with normal BMI | −2.724 | .006 | |

| Companion with underweight BMI vs with overweight BMI | −0.535 | .592 | |

| Companion with underweight BMI vs with obese BMI | −0.284 | .776 | |

| Companion with normal BMI vs with overweight BMI | −1.174 | .240 | |

| Companion with normal BMI vs with obese BMI | −1.186 | .235 | |

| Companion with overweight BMI vs with obese BMI | −0.333 | .739 | |

| Comparison of patient’s prepregnancy BMI to clinician’s own BMI | A lot lower vs lower | 0.000 | > .99 |

| A lot lower vs the same | 0.000 | > .99 | |

| A lot lower vs higher | −1.834 | .067 | |

| A lot lower vs a lot higher | −2.107 | .035 | |

| Lower vs the same | −0.447 | .655 | |

| Lower vs higher | −1.563 | .118 | |

| Lower vs a lot higher | −1.903 | .057 | |

| The same vs higher | −2.025 | .043 | |

| The same vs a lot higher | −2.358 | .018 | |

| Higher vs a lot higher | −2.310 | .021 | |

| Degree to which the clinic is running on time | On time vs 30 min late | −6.422 | < .001 |

| On time vs 60 min late | −6.276 | < .001 | |

| 30 min late vs 60 min late | −4.111 | < .001 | |

| Time allotted to prenatal visit | 30 min vs 20 min | −4.667 | < .001 |

| 30 min vs 15 min | −5.872 | < .001 | |

| 30 min vs 10 min | −6.296 | < .001 | |

| 20 min vs 15 min | −5.300 | < .001 | |

| 20 min vs 10 min | −5.333 | < .001 | |

| 15 min vs 10 min | −4.507 | < .001 |

BMI—body mass index, SES—socioeconomic status.

Pertaining to patient factors, clinician self-efficacy scores were significantly higher for older patients compared with younger patients (P = .001), when patients were nulliparous compared with primiparous or multiparous (P = .006), and when patients had a higher compared with a lower SES (P < .001). There was no significant difference between the presence of 1 or several weight-related comorbidities.

When interpersonal factors were considered, self-efficacy scores were significantly higher with greater clinician knowledge of the patient (P < .001), when the clinician understood the patient’s cultural background compared with when there was no such understanding (P < .001), and with higher clinician rating of the quality of the clinician-patient relationship (P < .001). Clinicians rated their self-efficacy to be highest when a patient attended the prenatal visit by herself compared with when she was accompanied by anyone else. Self-efficacy scores tended to be lower when clinicians perceived the patient’s prepregnancy BMI to be higher than their own BMIs.

With regard to clinic factors, self-efficacy scores were significantly higher when the clinic was running on time versus running late, and there were significant differences in self-efficacy scores depending on the time available for the prenatal appointment (P < .001 for both), with more time being associated with higher scores. Notably, even the comparison of a 15-minute versus a 10-minute appointment was associated with significantly higher self-efficacy scores (P < .001).

DISCUSSION

While a number of factors have been identified as increasing or decreasing the likelihood that clinicians would raise the issue of excess gestational weight gain with their patients, to the author’s knowledge, this is the first theory-driven study to explore clinicians’ perspectives of how various scenarios affect their perceived self-efficacy in raising the subject.

Outside of prenatal care, there have been a number of interventions to address some of the barriers identified by clinicians wishing to have weight-related discussions with their patients, including training in behaviour change counseling36,37 and the use of point-of-care tools.38 Such interventions have shown some promise in terms of patient health behaviour and health outcomes,39,40 and in particular, have demonstrated a 2-fold increase in clinician initiation of weight-related discussions with their patients.41

With the recent increased attention on gestational weight gain and its short- and long-term health implications for both mothers and their children, it is prudent to translate this momentum to the prenatal care period, a period that has been dubbed a “teachable moment.”42 However, it is not sufficient to focus solely on behaviour change initiatives that target patients—efforts should also be directed toward prenatal care providers. Previous studies have shown an inconsistency between patients’ and clinicians’ reports of whether discussions about gestational weight gain actually take place.13,15 Perhaps this is partly owing to the manner in which these discussions are initiated and conducted,43 and interventions as described above could address this problem. The Canadian Obesity Network recently launched a tool for prenatal care providers, The “5 As of Healthy Pregnancy Weight Gain,”44 the development of which was informed by the patient-centred clinical method45 and behaviour change theory. At the core of this tool is the philosophy that advice provided to patients should be given in the context of having first understood the whole person (ie, the patient’s context) so that common ground can be found. Led by behaviour change specialists, current work is under way in a number of regions throughout Canada to develop standardized training modules relevant to this tool and to evaluate the effect of training clinicians in the use of this tool. This study adds to the literature and will inform this endeavour by providing the clinicians’ perspectives on where their challenges lie pertaining to having discussions about gestational weight gain with their patients.

Limitations

Although clinician self-efficacy in discussing gestational weight gain with their patients was clearly vulnerable to system issues and to the patient-clinician relationship, it was nonetheless fairly high overall. This is somewhat surprising considering previous work demonstrating that prenatal care providers do not frequently raise the subject with their patients and that they perceive such discussions to be difficult owing to the generally sensitive nature of weight-related discussions. This reflects a potential weakness of the study—perhaps the participants were not truly representative of prenatal care providers in general, as they had self-selected to be part of the College of Family Physicians of Canada’s maternity list server and were therefore likely to be providers of low-risk prenatal care with an interest in prenatal care. Assuming this to be true, the current study would reflect the best-case scenario in terms of self-efficacy scores, but the relative self-efficacy scores for items within categories would likely persist.

Conclusion

Understanding the perspectives of prenatal care providers is an important step for clinicians, researchers, and decision makers interested in developing interventions that are relevant to these clinicians and address their concerns. Such undertakings could likely benefit not only the clinicians, but ultimately the women and families for whom they provide clinical care.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

This is the first theory-driven study to explore clinicians’ perspectives of how a variety of scenarios affect their perceived self-efficacy in raising the subject of excess gestational weight gain.

Self-efficacy was highest (mean [SD] 8.97 [1.34]) if the clinician could externalize the reason for undertaking the discussion, ie, if the patient had existing weight-related comorbidities. Conversely, self-efficacy was lowest (mean [SD] 5.14 [3.24]) with system issues, ie, if the clinic was running 60 minutes late.

Although clinician self-efficacy in discussing gestational weight gain with their patients was clearly vulnerable to system issues and to the patient-clinician relationship, it was nonetheless fairly high overall. This is somewhat surprising considering previous work demonstrating that prenatal care providers do not frequently raise the subject with their patients and that they perceive such discussions to be difficult owing to the generally sensitive nature of weight-related discussions.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Il s’agit de la première étude axée sur la théorie visant à explorer le point de vue des cliniciens sur la façon dont divers scénarios influent sur leur perception de leur efficacité personnelle à soulever le sujet d’un gain pondéral gestationnel trop élevé.

La perception de sa propre efficacité était la plus élevée (moyenne [ET] de 8,97 [1,34]) si le clinicien pouvait exprimer la raison d’amorcer la discussion, par exemple, si la patiente avait déjà des comorbidités liées au poids. À l’inverse, la perception de sa propre efficacité était la plus basse (moyenne [ET] de 5,14 [3,24]) en présence de problèmes systémiques, par exemple, si la clinique accusait 60 minutes de retard dans les rendez-vous.

Même si l’efficacité perçue par le clinicien luimême à discuter du gain pondéral gestationnel avec leurs patientes était clairement sensible aux problèmes du système et à la relation patientemédecin, elle était néanmoins plutôt élevée dans l’ensemble. Cette constatation est quelque peu surprenante compte tenu de travaux antérieurs faisant valoir que les professionnels qui offrent des soins prénatals soulèvent rarement ce sujet avec leurs patientes et ont l’impression que ces discussions sont difficiles en raison de la nature généralement délicate des conversations relatives au poids.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Viswanathan M, Siega-Riz AM, Moos MK, Deierlein A, Mumford S, Knaack J, et al. Outcomes of maternal weight gain. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2008;(168):1–223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cedergren MI. Optimal gestational weight gain for body mass index categories. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(4):759–64. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000279450.85198.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu SY, Callaghan WM, Bish CL, D’Angelo D. Gestational weight gain by body mass index among US women delivering live births, 2004–2005: fueling future obesity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(3):271.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.879. Epub 2009 Jan 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasmussen KM, Catalano PM, Yaktine AL. New guidelines for weight gain during pregnancy: what obstetrician/gynecologists should know. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;21(6):521–6. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328332d24e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies GAL, Maxwell C, McLeod L, Gagnon R, Basso M, Bos H, et al. Obesity in pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;110(2):167–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crane JM, White J, Murphy P, Burrage L, Hutchens D. The effect of gestational weight gain by body mass index on maternal and neonatal outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31(1):28–35. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)34050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kowal C, Kuk J, Tamim H. Characteristics of weight gain in pregnancy among Canadian women. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(3):668–76. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0771-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perinatal Epidemiology Research Unit. Nova Scotia Atlee Perinatal Database report of indicators: 2002–2011. Halifax, NS: Dalhousie University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cogswell ME, Scanlon KS, Fein SB, Schieve LA. Medically advised, mother’s personal target, and actual weight gain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(4):616–22. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stotland NE, Haas JS, Brawarsky P, Jackson RA, Fuentes-Afflick E, Escobar GJ. Body mass index, provider advice, and target gestational weight gain. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(3):633–8. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000152349.84025.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phelan S, Phipps MG, Abrams B, Darroch F, Schaffner A, Wing RR. Practitioner advice and gestational weight gain. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20(4):585–91. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2316. Epub 2011 Mar 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stengel MR, Kraschnewski JL, Hwang SW, Kjerulff KH, Chuang CH. “What my doctor didn’t tell me”: examining health care provider advice to overweight and obese pregnant women on gestational weight gain and physical activity. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(6):e535–40. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duthie EA, Drew EM, Flynn KE. Patient-provider communication about gestational weight gain among nulliparous women: a qualitative study of the views of obstetricians and first-time pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:231. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonald SD, Pullenayegum E, Taylor VH, Lutsiv O, Bracken K, Good C, et al. Despite 2009 guidelines, few women report being counseled correctly about weight gain during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(4):333.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.05.039. Epub 2011 May 27. Erratum in: Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212(1):102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lutsiv O, Bracken K, Pullenayegum E, Sword W, Taylor VH, McDonald SD. Little congruence between health care provider and patient perceptions of counselling on gestational weight gain. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34(6):518–24. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald SD, Pullenayegum E, Bracken K, Chen AM, McDonald H, Malott A, et al. Comparison of midwifery, family medicine, and obstetric patients’ understanding of weight gain during pregnancy: a minority of women report correct counselling. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34(2):129–35. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waring ME, Moore Simas TA, Barnes KC, Terk D, Baran I, Pagoto SL, et al. Patient report of guideline-congruent gestational weight gain advice from prenatal care providers: differences by prepregnancy BMI. Birth. 2014;41(4):353–9. doi: 10.1111/birt.12131. Epub 2014 Sep 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willcox JC, Campbell KJ, McCarthy EA, Lappas M, Ball K, Crawford D, et al. Gestational weight gain information: seeking and sources among pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:164. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0600-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stotland NE, Gilbert P, Bogetz A, Harper CC, Abrams B, Gerbert B. Preventing excessive weight gain in pregnancy: how do prenatal care providers approach counseling? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19(4):807–14. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willcox JC, Campbell KJ, van der Pligt P, Hoban E, Pidd D, Wilkinson S. Excess gestational weight gain: an exploration of midwives’ views and practice. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang T, Llanes M, Gold KJ, Fetters MD. Perspectives about and approaches to weight gain in pregnancy: a qualitative study of physicians and nurse midwives. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oken E, Switkowski K, Price S, Guthrie L, Taveras EM, Gillman M, et al. A qualitative study of gestational weight gain counseling and tracking. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(8):1508–17. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1158-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight-Agarwal CR, Kaur M, Williams LT, Davey R, Davis D. The views and attitudes of health professionals providing antenatal care to women with a high BMI: a qualitative research study. Women Birth. 2014;27(2):138–44. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2013.11.002. Epub 2013 Dec 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrari RM, Siega-Riz AM. Provider advice about pregnancy weight gain and adequacy of weight gain. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(2):256–64. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-0969-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stotland N, Tsoh JY, Gerbert B. Prenatal weight gain: who is counseled? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21(6):695–701. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2922. Epub 2011 Nov 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herring SJ, Platek DN, Elliott P, Riley LE, Stuebe AM, Oken E. Addressing obesity in pregnancy: what do obstetric providers recommend? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19(1):65–70. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van der Pligt P, Campbell K, Willcox J, Opie J, Denney-Wilson E. Opportunities for primary and secondary prevention of excess gestational weight gain: general practitioners’ perspectives. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilkinson SA, Poad D, Stapleton H. Maternal overweight and obesity: a survey of clinicians’ characteristics and attitudes, and their responses to their pregnant clients. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heslehurst N, Newham J, Maniatopoulos G, Fleetwood C, Robalino S, Rankin J. Implementation of pregnancy weight management and obesity guidelines: a metasynthesis of healthcare professionals’ barriers and facilitators using the theoretical domains framework. Obes Rev. 2014;15(6):462–86. doi: 10.1111/obr.12160. Epub 2014 Mar 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. 1982;37(2):122–47. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bandura A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In: Pajares F, Urdan TC, editors. Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing; 2006. pp. 307–37. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Picard A. Midwives: underused and misused assets in Canada. Globe and Mail. 2013 Jul 10; [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kling J. A call for greater cooperation between ob-gyns and midwives. New York, NY: Medscape; 2011. Available from: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/742508. Accessed 2015 Nov 18. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hastie C, Fahy K. Inter-professional collaboration in delivery suite: a qualitative study. Women Birth. 2011;24(2):72–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2010.10.001. Epub 2010 Nov 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sargeant J, Valli M, Ferrier S, MacLeod H. Lifestyle counseling in primary care: opportunities and challenges for changing practice. Med Teach. 2008;30(2):185–91. doi: 10.1080/01421590701802281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Borch-Johnsen K, Christensen B. General practitioners trained in motivational interviewing can positively affect the attitude to behaviour change in people with type 2 diabetes. One year follow-up of an RCT, ADDITION Denmark. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2009;27(3):172–9. doi: 10.1080/02813430903072876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vallis M, Piccinini-Vallis H, Sharma AM, Freedhoff Y. Modified 5 As. Minimal intervention for obesity counseling in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:27–31. (Eng), e1–5 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chossis I, Lane C, Gache P, Michaud PA, Pécoud A, Rollnick S, et al. Effect of training on primary care residents’ performance in brief alcohol intervention: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(8):1144–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0240-2. Epub 2007 May 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollak KI, Alexander SC, Coffman CJ, Tulsky JA, Lyna P, Dolor RJ, et al. Physician communication techniques and weight loss in adults: Project CHAT. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(4):321–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rueda-Clausen CF, Benterud E, Bond T, Olszowka R, Vallis MT, Sharma AM. Effect of implementing the 5As of obesity management framework on provider-patient interactions in primary care. Clin Obes. 2013;4(1):39–44. doi: 10.1111/cob.12038. Epub 2013 Oct 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phelan S. Pregnancy: a “teachable moment” for weight control and obesity prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(2):135.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.008. Epub 2009 Aug 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Butler C, Rollnick S, Stott N. The practitioner, the patient and resistance to change: recent ideas on compliance. CMAJ. 1996;154(9):1357–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Canadian Obesity Network. 5As of healthy pregnancy weight gain. Edmonton, AB: Canadian Obesity Network; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR. Patient-centered medicine. Transforming the clinical method. 3rd ed. London, UK: Radcliffe Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]