Abstract

Background

The American College of Surgeons and American Geriatrics Society recommend performing a geriatric assessment (GA) in the preoperative evaluation of older patients. To address this, we developed an electronic GA; the Electronic Rapid Fitness Assessment (eRFA). We reviewed the feasibility and clinical utility of the eRFA in the preoperative evaluation of geriatric patients.

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of our experience using the eRFA in the preoperative assessment of geriatric patients. The rate of and time to completion of the eRFA were recorded. The first 50 patients who completed the assessment were asked additional questions to assess their satisfaction. Descriptive statistics of patient-reported geriatric-related data were used for analysis.

Results

In 2015, 636 older cancer patients (median age, 80 years) completed the eRFA during preoperative evaluation. The median time to completion was 11 minutes (95% CI, 11 to 12 minutes). Only 13% of patients needed someone else to complete the assessment for them. Of the first 50 patients, 90% (95% CI, 75% to 98%) responded that answering questions by using eRFA was easy. Geriatric syndromes were commonly identified through the performance of the GA: 16% of patients had a positive screening for cognitive impairment, 22% (95% CI, 19% to 26%) needed a cane to ambulate, and 26% (95% CI, 23% to 30%) had fallen at least once during the previous year.

Conclusion

Implementation of the eRFA was feasible. The eRFA identified relevant geriatric syndromes in the preoperative setting that, if addressed, could lead to improved outcomes.

Introduction

Older cancer patients have a higher risk of developing postoperative surgical complications,1 including delirium2 and prolonged hospital length of stay,3 and have poorer overall survival,4 compared with younger patients. Although a significant number of studies have investigated the effects of age on surgical outcomes, others have argued that overall fitness, rather than age, should be the chief consideration in surgical decision-making.5 Frailty, as opposed to fitness, is a state of preexisting limited organ and functional reserve in response to stress (e.g., surgery and/or cancer).6 Preoperative age-related deficits (or geriatric syndromes) have been shown to be associated with a higher risk of postoperative mortality, institutionalization, and delirium in older patients undergoing cancer and noncancer-related surgery.7 Older cancer patients with slower walking pace, poorer nutritional status, higher number of medications taken, and more comorbid conditions have poorer surgical outcomes.8–10 A patient’s level of frailty can be determined by geriatric assessment (GA),11 which is a multidimensional evaluation encompassing several functional and psychosocial domains. Various organizations have recommended incorporating GA into the assessment of older cancer patients.12–14

Despite these recommendations, the inclusion of GA in the preoperative assessment of older cancer patients has been poor. Recently, the Surgical Task Force at the International Society of Geriatric Oncology found that, of 251 surgeons who responded to a questionnaire concerning their attitudes about the preoperative assessment of older cancer patients (11% response rate), only 48% considered a preoperative frailty assessment to be mandatory, only 6% used GA in daily practice, and only 34% collaborated with geriatricians.15 These poor compliance rates likely stem from the practical difficulties of implementing GA in routine surgical practice.

To increase the rate of performance of GA in the preoperative setting, we developed a patient-centered assessment that is feasible and effective, with no added burden for the provider. We have found that the key to successful implementation of this GA is to have the patient complete it online, using an electronic tablet, with the results automatically collated and reported to the treating clinician. In this paper, we review our experience with the development and implementation of an electronic GA, which we have called the Electronic Rapid Fitness Assessment, or eRFA.

Materials and Methods

Data Collection and Analysis

We performed a retrospective review of our institution’s experience using the eRFA in the routine and elective preoperative evaluation of geriatric cancer patients who presented to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) geriatrics clinics in 2015. To assess and improve the quality of patient and/or caregiver interactions with the eRFA, data on time to complete the eRFA and the person who completed the eRFA were collected. The first 50 patients who completed the eRFA were asked additional questions to assess their satisfaction with the process. Descriptive statistics of patient-reported geriatric-related data were used for analysis. The Institutional Review Board at MSKCC approved this study.

Referral to Geriatrics Service for Preoperative Assessment

At MSKCC, patients aged ≥75 years who are willing to be assessed by MSKCC Geriatrics Service, instead of their primary care provider, are referred to the Geriatrics Service. Surgeons may also refer younger patients who have geriatric syndromes, such as cognitive deficits, functional decline, or multiple comorbidities.

Project Site

The eRFA was developed at MSKCC through collaboration between the Geriatrics Service and the Web Survey Core Facility (Webcore). The service performs preoperative assessments of approximately 900 older cancer patients annually. The MSKCC Webcore is a National Cancer Institute–funded core facility that was created to develop and administer secure online questionnaires.

Development of the eRFA

During the eRFA development process, the Geriatrics Service held multiple discussions to determine which GA domains to assess and which validated assessment methods to use (Table 1). The name “Electronic Rapid Fitness Assessment” was selected to reflect the purpose of the GA, which is to distinguish patients who are fit from those who are frail.

Table 1.

Electronic Rapid Fitness Assessment Domains and Instruments

| Domain | Assessment tool | Description and score range (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|

| Functional status | Karnofsky Performance Scale (rated by the patient)34 | 30 to 100, in increments of 1030 means severely disabled; 100 means normal without any symptoms. |

| Activities of Daily Living (ADL)35–37 | 7 activities: bathing, dressing, grooming, feeding, walking inside the home, walking outside the home, and bladder and bowel control. Patients get 2 points for each activity that is not limited at all, 1 point for limited a little, and 0 points for limited a lot. Total ADL score ranges from 0 to 14. | |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (iADL)38,39 | 8 activities: telephone use, doing laundry, shopping, preparing meals, doing housework, handling own medications, handling money and finances, and transportation to visit one’s doctor. Patients get 2 points for activity that can be done without help, 1 point for some help, and 0 point for being unable to do. Total iADL score ranges from 0 to 16. | |

| Timed Up and Go40–42 | Patients are asked to get up from the chair, walk 10 feet, turn, and walk back to the chair (<10 seconds, 10–20 seconds, >20 seconds). | |

| History and number of falls in the past year, context of fall |

|

|

| Use of assistive devices | Use of cane, walker, or wheelchair | |

| Cognition | Mini-Cog test43 | Clock-drawing test (CDT) and 3-word recall. Normal CDT gets 2 points, and each recalled word gets 1 point. Score ranges from 0 to 5. Score of ≤2 is indicative of cognitive deficit. |

| Social support | Four-item Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey44 | Four 5-point Likert scale questions addressing 4 domains of social support: emotional/informational, tangible, affectionate, and positive social interaction. Score for each item ranges from 1 to 5, and total score ranges from 4 to 20. A higher score means better social support. |

| Social activity interference | Medical Outcomes Study Social Activity Survey45 | Three 5-point Likert scale questions addressing the interference of patient’s health condition with the social activity. Total score ranges from 3 to 15. Higher score means more health-related interference with social activities. |

| Emotional status | Distress Thermometer46–50 | Score ranges from 0 to 10. 0 means no distress at all; 10 means extreme distress. Score of ≥4 is suggestive of high level of distress. |

| Geriatrics Depression Scale 4-item questionnaire51 | Four yes/no questions regarding patient’s psychological status. Score ranges from 0 to 4, and a score of ≥1 is usually indicative of depression. | |

| Nutrition status | Single item on weight change during the past 6 months. Items range from “No weight change”/”Weight gain” to “Weight loss of >20 lbs.” | |

| Vision | Questions about vision quality (excellent, good, fair, poor), wearing eyeglasses (yes, no), and effectiveness of eyeglasses in improving vision (a great deal, somewhat, not at all). | |

| Hearing | Questions about hearing quality (excellent, good, fair, poor), wearing hearing aid (yes, no), and effectiveness of hearing aid in improving hearing (a great deal, somewhat, not at all). | |

| Polypharmacy28 |

|

|

Administration of the eRFA

All patients who present to MSKCC geriatric clinics complete the eRFA while they are waiting to be seen by a geriatrician for their initial consultation. Patients may complete the eRFA on their own or with assistance from others (e.g., a caregiver), or they may allow someone else (e.g., a caregiver) to complete the assessment for them. Patients may also complete the eRFA at home, before their appointment, if they have Internet access and an email account. After the assessment has been completed, an RN performs a cognitive assessment using the Mini-Cog16 and establishes the patient’s mobility using the Timed Up and Go (TUG)17 test, the results of which are then entered into the eRFA by the RN.

Quality and Quantity Assurance

The leader of the project (A.S.), with the help of the Webcore staff, has been responsible for monitoring the quality and quantity of the eRFAs. As a result of this process, the final report of the eRFA was revised to highlight missing data, and health care providers were asked to review the final report with the patients to make necessary corrections to ensure completion.

Results

Pilot Phase

Time to Complete the eRFA

The pilot phase of this project ran from January 2015 to April 2015, with an average of 22 eRFA surveys completed each month for either preoperative assessment or other geriatric consultation. The median time to complete the eRFA was 15 minutes (95% CI, 13 to 17 minutes), and 83% of patients (95% CI, 73% to 90%) were able to complete the eRFA in ≤25 minutes.

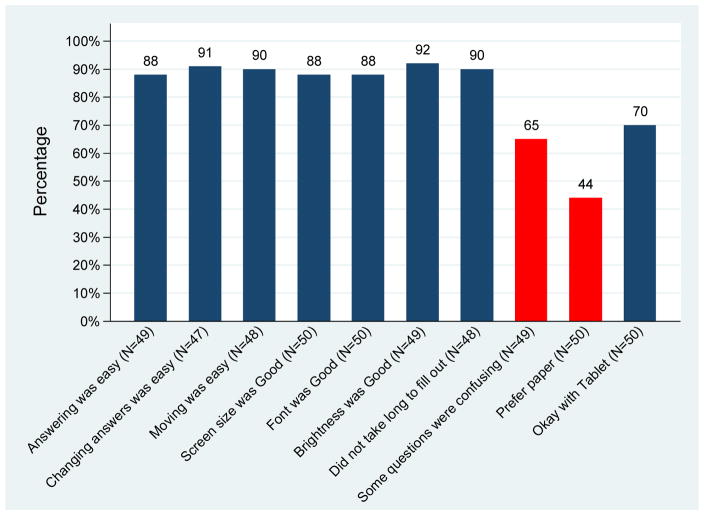

Satisfaction Survey

To assess patient and caregiver satisfaction with the content and delivery of the eRFA, the first 50 patients who completed the eRFA were given a 16-item satisfaction questionnaire. The questionnaire included three sociodemographic questions (age, education, and gender); three technology questions (about the computer, the handheld device, and the availability of Internet access at home); and 10 questions regarding the patient’s experience with the eRFA (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient satisfaction with the Electronic Rapid Fitness Assessment (blue bars represent strong and somewhat agreement; red bars represent strong and somewhat disagreement).

Of the 50 individuals who completed this questionnaire, 22% were <75, 30% were 75–79, 36% were 80–84, and 12% were ≥85 years old. Sixty-four percent were women, 38% had a high school diploma or less, 34% were college graduates or had some college education, and 28% had an advanced degree. As shown in Figure 1, approximately 90% (respective 95% CI, 75% to 98%) of patients responded that answering questions, changing answers, and moving between questions were easy.

Expansion Phase

Use of the eRFA was expanded to all geriatric clinics in May 2015, leading to a significant increase in the number of monthly completions. In total, 1024 older cancer patients completed the eRFA, 636 of whom had presented to a geriatric clinic for preoperative assessment. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the preoperative patient cohort are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohort (N=636)

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, median (interquartile range) | 80 (77 to 84) |

| Female | 331 (52) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 338 (53) |

| Widowed | 180 (28) |

| Divorced | 50 (8) |

| Single | 44 (7) |

| Domestic partnership | 13 (2) |

| Separated | 9 (1) |

| Unknown | 2 (<1) |

| Education level | |

| Advanced degree | 151 (24) |

| College graduate | 148 (23) |

| Some college | 108 (17) |

| High school diploma | 159 (25) |

| Less than high school diploma | 62 (10) |

| Unknown | 8 (1) |

| Living situation | |

| Living with family or partner | 411 (65) |

| Living alone | 201 (32) |

| Living with someone who is not family/a partner | 7 (1) |

| Assisted living facility | 3 (1) |

| Nursing home | 1 (<1) |

| Other | 8 (1) |

| Unknown | 5 (1) |

| Race | |

| White | 514 (81) |

| Black | 38 (6) |

| Asian | 25 (4) |

| Refused to answer | 44 (7) |

| Other | 4 (1) |

| Missing | 11 (2) |

| Surgery type | |

| Ambulatory | 296 (47) |

| Surgery requiring hospitalization | 340 (53) |

| Surgical site | |

| Genitourinary | 162 (25) |

| Head and neck | 85 (13) |

| Colorectal | 78 (12) |

| Gynecological | 60 (9) |

| Hepatopancreatic | 49 (8) |

| Breast | 36 (6) |

| Thoracic | 37 (6) |

| Gastric/mixed | 38 (6) |

| Ophthalmic | 33 (5) |

| Neurosurgery | 21 (3) |

| Orthopedic | 17 (3) |

| Other | 18 (3) |

| Unknown | 2 (<1) |

The following sections summarize the additional data obtained by administration of the eRFA to these preoperative patients.

Completion of the eRFA

In this larger group, the median time to complete the eRFA was 11 minutes (95% CI, 11 to 12 minutes), and 90% (95% CI, 88% to 93%) of patients were able to complete the eRFA in ≤25 minutes. Of the 636 preoperative eRFAs completed in 2015, 315 (50%) were completed by the patients, 236 (37%) were completed with assistance, and 82 (13%) were completed by another person (likely a caregiver).

eRFA Results

1-Functional Domain

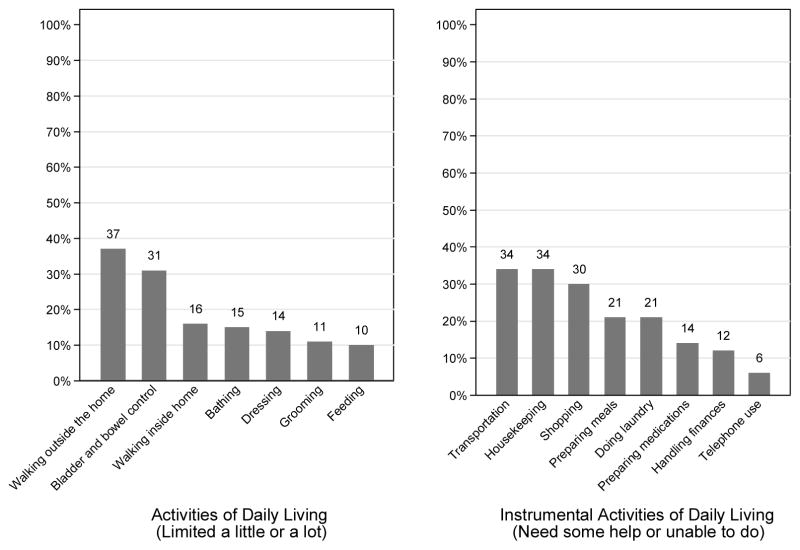

The median (range) of patient-rated Karnofsky Performance Scale score was 90 (30 to 100). Overall, 26% (95% CI, 23% to 30%) of patients experienced at least 1 fall during the previous year. Of the patients who experienced a fall, 37% (95% CI, 30% to 45%) had >1 fall. Of the 161 patients who reported the location of the fall, a slim majority experienced their last fall at home, rather than outside the home (56% vs. 44%). In total, 22% (95% CI, 19% to 26%), 11% (95% CI, 9% to 14%), and 4% (95% CI, 3% to 6%) of patients presented to the geriatric clinic using a cane, a walker, and a wheelchair, respectively. The time to complete the TUG test was <10 seconds for 353 patients (56%), 10 to 19 seconds for 147 patients (23%), and >20 seconds for 62 patients (10%). The remaining 74 patients had missing data (see Quality and Quantity Assurance). Patients’ levels of independence for activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living are shown in Figure 2 (supplemental).

Figure 2.

Patients’ limitations in activities of daily of living and instrumental activities of daily living.

2-Cognition

In total, 334 patients (58%) were able to recall 3 words, 149 (26%) were able to recall 2 words, 68 (12%) were able to recall 1 word, and 20 (4%) could recall no words. Results of the clock-drawing test were normal for 425 patients (74%) and abnormal for 146 (26%). Overall, 16% of patients had a positive screening for cognitive impairment (Mini-Cog score of ≤2). It should be noted that 65 patients had missing data (see Quality and Quantity Assurance).

3-Social Support and Social Activity Interference

Among our cohort, more patients expressed having adequate support (defined by all or most of the time) in affectionate domain (83%), than positive social interaction (75%), emotional/informational support (71%) or tangible support (57%). Responding to impact of their health/emotional condition on their social activities, 39% thought they were somewhat or much more limited than 6 months ago, and 24% thought they were somewhat or much more limited than their peers.

4-Emotional Status

The median distress score for this cohort was 4, with 31% of patients (95% CI, 28% to 35%) experiencing a distress score of ≥6. The median Geriatric Depression Scale four-item score was 1.

5-Nutrition Status

In total, 282 patients (44%) reported no weight loss during the previous 6 months, compared with 111 (17%) who lost <5 pounds, 111 (17%) who lost 5 to 10 pounds, 52 (8%) who lost 10 to 20 pounds, and 38 (6%) who lost >20 pounds; 42 patients (7%) did not know whether or by how much their weight changed during the previous 6 months.

6-Sensory Deficit

Of the patients who presented for preoperative evaluation, 7% (95% CI, 5% to 9%) considered their vision quality to be poor, and 24% (95% CI, 21% to 28%) considered their vision quality to be fair. Reported hearing quality was poor for 15% (95% CI, 13% to 18%) and fair for 27% (95% CI, 24% to 31%) of patients.

7-Polypharmacy

In total, 585 patients (92%) took at least 1 medication. Among these patients, 50% (95% CI, 46% to 54%) took 1 to 4 medications, 38% (95% CI, 34% to 42%) took 5 to 10 medications, and 5% (95 CI, 4% to 8%) took >10 medications. Forty patients did not provide details about the number of medications they took.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show the feasibility and utility of performing an electronic GA in the preoperative assessment of older cancer patients. The median time to complete the eRFA for preoperative assessment was an acceptable 11 minutes, which is similar to the time it takes to complete a screening assessment (rather than a complete GA)18 and is much shorter than the time reported to complete a paper-version GA (30 minutes).19 In addition, the majority of patients were able to complete the eRFA on their own or with assistance from a caregiver.

Through the use of the eRFA, aging-related deficits (geriatric syndromes) were discovered that otherwise might have gone unnoticed. Among our cohort, 16% had a positive screening for cognitive deficit on the basis of the Mini-Cog assessment. Studies have shown that patients with cognitive deficits have a higher risk of postoperative delirium,20 which may lead to prolonged hospital stay and other complications.21 A substantial percentage of patients (37%) had limitations walking outside the home, and almost the same percentage of patients expressed the need for assistance with transportation. These findings are important; as such limitations may jeopardize a patient’s ability to adhere to postoperative follow-up recommendations by surgeons or other health care providers. Approximately one-quarter of our patients experienced at least 1 fall during the year before their surgical procedure, and more than half of these falls occurred at home. This raises the need for postoperative physical therapy and home safety assessment for these patients.22

More than half of our patients expressed a high level of distress, and interventions such as referral to a social worker should be considered.23 In total, 14% of patients experienced weight loss of >10 pounds during the previous 6 months, reflecting the need for nutritionist involvement.24 Poor or fair hearing quality—identified in 15% and 27% of patients—may jeopardize patients’ inpatient postoperative course as well as their ability to understand care instructions, which may increase the likelihood of hospital readmission and functional decline.25,26 Polypharmacy was present in approximately 40% of patients. In a study of patients with gastric adenocarcinoma undergoing gastrectomy, those with polypharmacy were 2.4 times more likely to develop major postoperative morbidity.27 In a population of community-dwelling men aged ≥70 years, polypharmacy was associated with an increased likelihood of frailty, disability, falls, and mortality.28 Therefore, to prevent postoperative complications, it is important to conduct a preoperative medication review to assess the appropriateness of the patient’s medications.

Prior small studies have shown the correlation between frailty and surgical outcomes in older cancer patients. In a study of 176 patients with colorectal cancer aged 70 to 94 years, postoperative complications and survival were strongly associated with frailty, which was defined as having 1 or more of the following conditions: activities of daily living dependency, severe comorbid conditions, cognitive deficit, depression, malnutrition, and taking >7 medications.29 Similarly, a study of 281 female cancer patients aged ≥65 years with an American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System score of 1 or 2 found that Multidimensional Frailty Score30 was associated with postoperative complications, increased likelihood of institutionalization, and prolonged hospital stay.31

Our study has several limitations. We tested the eRFA in a single institution with a patient population that may not be reflective of older community-dwelling patients elsewhere. Approximately 65% of our cohort had at least some college education. Studies have shown that, among older patients, higher education levels are associated with better acceptance of computers.32,33 It remains to be seen whether eRFA compliance levels in community clinics and among less-educated patients will be as high as those we experienced in this study. Moreover, the eRFA was included as part of a preoperative assessment within MSKCC’s geriatric clinics. Future studies should focus on implementing the eRFA in surgical oncology clinics and assessing patient and clinician satisfaction.

The highlight of our study is the development and successful implementation of the first patient-friendly electronic GA, which we have shown to be feasible to implement in routine clinical practice and which effectively identifies patients with geriatric syndromes. Future projects related to this work include the following: (1) We will combine data obtained through the use of the eRFA with the MSKCC Surgical Outcomes Dataset to evaluate the correlation between aging-related deficits and surgical outcomes among older cancer patients. (2) We will strive to implement the eRFA in all surgical oncology clinics at our institution so that older cancer patients, regardless of whether they are referred to the Geriatrics Service, can be evaluated comprehensively. (3) Finally, we will test the effectiveness of the eRFA in improving postoperative outcomes among older cancer patients by conducting a prospective, randomized trial among this patient population.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: The project was supported, in part, by the Beatriz and Samuel Seaver Foundation, the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer and Aging Program, and NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

The authors acknowledge the constant support of the Geriatrics Service registered nurses, nurse practitioners, physician office assistants, session assistants, and Webcore staff. We wholeheartedly appreciate the contributions of all of our older cancer patients, their families, and their caregivers. Without their collaboration, this project would not have been feasible. We appreciate the guidance from former Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Chair of the Department of Medicine Dr. George Bosl. Authors confirm that they do not have any competing interest with regard to the conducted study and its result.

Footnotes

Presentation: This study was presented, in part, at the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2016 Annual Meeting.

Disclaimers: The authors declare no conflicts of interest and have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Kaibori M, Ishizaki M, Matsui K, et al. Geriatric assessment as a predictor of postoperative complications in elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2016;401:205–214. doi: 10.1007/s00423-016-1388-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasegawa T, Saito I, Takeda D, et al. Risk factors associated with postoperative delirium after surgery for oral cancer. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015;43:1094–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright CD, Gaissert HA, Grab JD, et al. Predictors of prolonged length of stay after lobectomy for lung cancer: a Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database risk-adjustment model. Anns Thorac Surg. 2008;85:1857–1865. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finlayson E, Fan Z, Birkmeyer JD. Outcomes in octogenarians undergoing high-risk cancer operation: a national study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.06.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manceau G, Karoui M, Werner A, et al. Comparative outcomes of rectal cancer surgery between elderly and non-elderly patients: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e525–e536. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70378-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Studenski S, et al. Designing randomized, controlled trials aimed at preventing or delaying functional decline and disability in frail, older persons: a consensus report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oresanya LB, Lyons WL, Finlayson E. Preoperative assessment of the older patient: a narrative review. JAMA. 2014;311:2110–2120. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huisman MG, van Leeuwen BL, Ugolini G, et al. “Timed Up & Go”: a screening tool for predicting 30-day morbidity in onco-geriatric surgical patients? A multicenter cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cesari M, Cerullo F, Zamboni V, et al. Functional status and mortality in older women with gynecological cancer. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:1129–1133. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badgwell B, Stanley J, Chang GJ, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment of risk factors associated with adverse outcomes and resource utilization in cancer patients undergoing abdominal surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2013;108:182–6. doi: 10.1002/jso.23369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korc-Grodzicki B, Downey RJ, Shahrokni A, et al. Surgical considerations in older adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2647–2653. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurria A, Wildes T, Blair SL, et al. Senior adult oncology, version 2.2014: clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:82–126. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology. Consensus on Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients with Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;20(32):2595–603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chow WB, Rosenthal RA, Merkow RP, et al. Optimal preoperative assessment of the geriatric surgical patient: a best practices guideline from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Coll Surg. 215:453–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghignone F, van Leeuwen BL, Montroni I, et al. The assessment and management of older cancer patients: A SIOG surgical task force survey on surgeons’ attitudes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, et al. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1451–1454. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed” Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sattar S, Alibhai SMH, Wildiers H, et al. How to implement a geriatric assessment in your clinical practice. Oncologist. 2014;19:1056–1068. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams GR, Deal AM, Jolly TA, et al. Feasibility of geriatric assessment in community oncology clinics. J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deiner S, Silverstein J. Postoperative delirium and cognitive dysfunction. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:i41–i46. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korc-Grodzicki B, Sun SW, Zhou Q, et al. Geriatric assessment as a predictor of delirium and other outcomes in elderly patients with cancer. Ann Surg. 2015;261:1085–1090. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pergolotti M, Williams GR, Campbell C, et al. Occupational therapy for adults with cancer: why it matters. Oncologist. 2016;21:314–319. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobsen PB, Ransom S. Implementation of NCCN distress management guidelines by member institutions. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5:99–103. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rowan NR, Johnson JT, Fratangelo CE, et al. Utility of a perioperative nutritional intervention on postoperative outcomes in high-risk head & neck cancer patients. Oral Oncol. 2016;54:42–6. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genther DJ, Betz J, Pratt S, et al. Association between hearing impairment and risk of hospitalization in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:1146–1152. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen DS, Betz J, Yaffe K, et al. Association of hearing impairment with declines in physical functioning and the risk of disability in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70:654–661. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pujara D, Mansfield P, Ajani J, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in patients with gastric and gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma undergoing gastrectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112:883–887. doi: 10.1002/jso.24077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:989–995. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kristjansson SR, Rønning B, Hurria A, et al. A comparison of two pre-operative frailty measures in older surgical cancer patients. J Geriatr Oncol. 2012;3:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim S, Han H, Jung H, et al. Multidimensional frailty score for the prediction of postoperative mortality risk. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:633–640. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi JY, Yoon SJ, Kim SW, et al. Prediction of postoperative complications using multidimensional frailty score in older female cancer patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Class 1 or 2. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:652–60.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vroman KG, Arthanat S, Lysack C. “Who over 65 is online?” Older adults’ dispositions toward information communication technology. Comput Human Behav. 2015;43:156–166. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shahrokni A, Mahmoudzadeh S, Saeedi R, et al. Older people with access to hand-held devices: who are they? Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:550–556. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mor V, Laliberte L, Morris JN, et al. The Karnofsky Performance Status Scale: An examination of its reliability and validity in a research setting. Cancer. 1984;53:2002–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840501)53:9<2002::aid-cncr2820530933>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, et al. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10:20–30. doi: 10.1093/geront/10.1_part_1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartigan I. A comparative review of the Katz ADL and the Barthel Index in assessing the activities of daily living of older people. Int J Older People Nurs. 2007;2:204–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2007.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoppe S, Rainfray M, Fonck M, et al. Functional decline in older patients with cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3877–3882. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.7430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bohannon RW. Reference values for the timed up and go test: a descriptive meta-analysis. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2006;29:64–8. doi: 10.1519/00139143-200608000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:664–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeung TS, Wessel J, Stratford PW, et al. The Timed Up and Go test for use on an inpatient orthopaedic rehabilitation ward. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38:410–7. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2008.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, et al. The Mini-Cog: a cognitive ‘vital signs’ measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:1021–7. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200011)15:11<1021::aid-gps234>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gjesfjeld CD, Greeno CG, Kim KH. a confirmatory factor analysis of an abbreviated social support instrument - The MOSS-SSS. Research on Social Work Practice. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stewart AL. Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hegel MT, Collins ED, Kearing S, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Distress Thermometer for depression in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2008;17:556–60. doi: 10.1002/pon.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, et al. Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 1998;82:1904–1908. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980515)82:10<1904::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mitchell AJ. Pooled results from 38 analyses of the accuracy of distress thermometer and other ultra-short methods of detecting cancer-related mood disorders. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4670–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ransom S, Jacobsen PB, Booth-Jones M. Validation of the Distress Thermometer with bone marrow transplant patients. Psychooncology. 2006;15:604–12. doi: 10.1002/pon.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holland JC, Bultz BD. The NCCN guideline for distress management: a case for making distress the sixth vital sign. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pomeroy IM, Clark CR, Philp I. The effectiveness of very short scales for depression screening in elderly medical patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:321–6. doi: 10.1002/gps.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]