Abstract

Shigella flexneri, a Gram-negative enteroinvasive pathogen, causes inflammatory destruction of the human intestinal epithelium. Infection by S. flexneri has been well-studied in vitro and is a paradigm for bacterial interactions with the host immune system. Recent work has revealed that components of the cytoskeleton have important functions in innate immunity and inflammation control. Septins, highly conserved cytoskeletal proteins, have emerged as key players in innate immunity to bacterial infection, yet septin function in vivo is poorly understood. Here, we use S. flexneri infection of zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae to study in vivo the role of septins in inflammation and infection control. We found that depletion of Sept15 or Sept7b, zebrafish orthologs of human SEPT7, significantly increased host susceptibility to bacterial infection. Live-cell imaging of Sept15-depleted larvae revealed increasing bacterial burdens and a failure of neutrophils to control infection. Strikingly, Sept15-depleted larvae present significantly increased activity of Caspase-1 and more cell death upon S. flexneri infection. Dampening of the inflammatory response with anakinra, an antagonist of interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R), counteracts Sept15 deficiency in vivo by protecting zebrafish from hyper-inflammation and S. flexneri infection. These findings highlight a new role for septins in host defence against bacterial infection, and suggest that septin dysfunction may be an underlying factor in cases of hyper-inflammation.

Author summary

Shigella are human-adapted Escherichia coli and cause bacillary dysentery via inflammatory destruction of the gut epithelium. In this study, we use a zebrafish (Danio rerio) model of Shigella infection to discover new roles for the cytoskeleton in inflammation and infection control. Septins, a poorly understood component of the cytoskeleton, are important in numerous biological processes including cell division and host-pathogen interactions. Here, we show that zebrafish septins can restrict inflammation and Shigella infection in vivo. In the absence of septins, larvae infected with Shigella exhibit increased mortality and bacterial burdens associated with increased Caspase-1 activity and neutrophil death. Pharmacological suppression of Il-1β signaling rescues septin-deficiency in vivo by reducing neutrophil death and preventing larval mortality. These findings reveal a new link between septins and inflammation, and highlight the cytoskeleton as a structural determinant of host defence.

Introduction

Septins, a poorly understood component of the cytoskeleton, are highly-conserved guanosine triphosphate (GTP) binding proteins organized into 4 groups based on sequence homology (the SEPT2, SEPT3, SEPT6, and SEPT7 groups). Septins from different groups assemble into hetero-oligomeric complexes which can form non-polar filaments and ring-like structures [1]. By acting as scaffolds for protein recruitment and diffusion barriers for cellular compartmentalization, septins have key roles in numerous biological processes, including cell division and host-pathogen interactions [1, 2]. Studies using human epithelial cells have revealed important roles for septins in cell-autonomous immunity, showing that septins assemble into cage-like structures to prevent the dissemination of cytosolic bacteria polymerizing actin tails [3–5]. Septin cages have also been observed in vivo using bacterial infection of zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae [6], yet roles for septins in innate immunity in vivo remain largely unexplored.

The inflammasome is an intracellular platform that assembles in response to infection to recruit and activate Caspase-1 [7]. Caspase-1 activation enables the processing and secretion of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin 1β (IL-1β) to control infection. How the inflammasome is triggered and assembled is the subject of intense investigation [8, 9], and the mechanisms underlying inflammation regulation are poorly understood [5]. New work has shown that components of the cytoskeleton play important roles in innate immunity and are required for inflammation control [5]. Actin and other proteins involved in actin polymerization regulate the NLRP3 (NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3) inflammasome by interacting with Caspase-1 and other inflammasome components [10–12]. A separate study showed that actin depolymerization, as a consequence of mutations in WD repeat-containing protein (WDR1), can trigger disease by activation of the pyrin inflammasome [13, 14]. Other components of the cytoskeleton, including microtubules and the intermediate filament protein vimentin, promote NLRP3 activity by helping to recruit ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-recruitment domain) and stabilize NLRP3 inflammasomes, respectively [15, 16]. The role of the septin cytoskeleton in inflammation control has not yet been tested.

Shigella, a Gram-negative enteroinvasive pathogen, causes nearly 165 million illness episodes and over 1 million deaths annually [17]. Similar to other Gram-negative pathogens in hospital patients, cases of drug-resistant Shigella strains are rising [18]. To explore the innate immune response to Shigella, several infection models have been valuable, helping to discover key roles for NOD-like receptors (NLRs) [19], neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [20], bacterial autophagy [21], and inflammasomes [22] in host defence. Remarkably, the major pathogenic events that lead to shigellosis in humans (i.e., macrophage cell death, invasion and multiplication within epithelial cells, cell-to-cell spread, inflammatory destruction of the host epithelium), are faithfully reproduced in a zebrafish model of S. flexneri infection [6]. Exploiting the optical accessibility of zebrafish larvae, we now have the possibility to spatio-temporally examine the biogenesis, architecture, coordination, and resolution of the innate immune response to S. flexneri in vivo.

In this study, we use a S. flexneri-zebrafish infection model to discover new roles for septins in host defence. We show that zebrafish septins restrict inflammation and are required for neutrophil-mediated immunity. To rescue septin-deficiency in vivo, we used therapeutic inhibition of Il-1β signaling and prevent neutrophil death and larval mortality. These results demonstrate a previously unknown role for septins in inflammation and infection control, and highlight the cytoskeleton as a target for suppression of inflammation.

Results

Establishment of localized S. flexneri infection in the zebrafish hindbrain ventricle

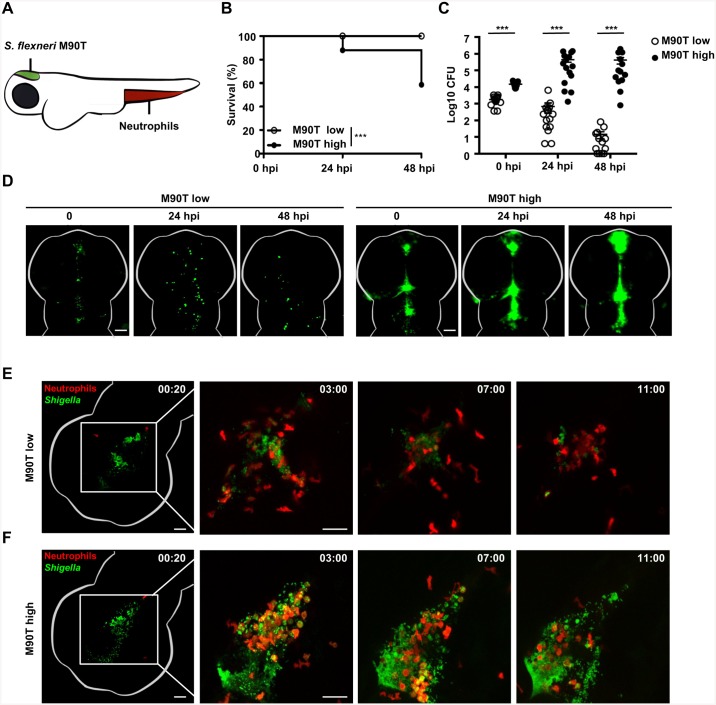

The hindbrain ventricle (HBV) of zebrafish larvae is uniquely suited to analyze host-pathogen interactions because it is optically accessible and enables analysis of a directed leukocyte response to a compartmentalized infection (Fig 1A). We therefore characterized the HBV of zebrafish larvae as an infection site for S. flexneri M90T. Larvae aged 3 days post fertilization (dpf) were microinjected with a low (≤ 3 x 103 CFU) or high (≥ 1 x 104 CFU) dose of bacteria and their survival was assessed over time (Fig 1B). Larvae infected with a low dose of S. flexneri presented 100% survival, whereas a high dose of S. flexneri resulted in the death of ~40% of larvae within 48 hours post infection (hpi). We measured the bacterial load of infected zebrafish larvae over time by plating homogenates of viable larvae, excluding those that had already succumbed to infection. Larvae infected with a low dose of S. flexneri controlled bacterial replication, whereas larvae receiving a high dose of S. flexneri were associated with an increasing bacterial burden (Fig 1C).

Fig 1. S. flexneri infection of the zebrafish hindbrain ventricle.

A. Cartoon of zebrafish larva (3 dpf) showing localization of neutrophils prior to infection (red) and the site of S. flexneri M90T (green) injection in the HBV. B. Survival curves of larvae infected with a low (≤ 3 x 103 CFU) or high (≥ 1 x 104 CFU) dose of S. flexneri M90T. Pooled data from 5 independent experiments per inoculum class using at least 15 larvae per experiment. Significance testing performed by Log Rank test. ***, P<0.001. C. Enumeration of bacteria at 0, 24, or 48 hpi from surviving larvae infected with a low (open circles) or high (closed circles) dose of S. flexneri M90T. Pooled data from 5 independent experiments per inoculum class using up to 3 larvae per treatment. Circles represent individual larvae, and only larvae having survived the infection (thus far) included here (i.e., dead larvae not homogenised for counts). Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by Student’s t test. ***, P<0.001. D. Representative images of larvae infected in the HBV with low or high dose of GFP-S. flexneri M90T. For each dose, the same larva was imaged at 0, 24, and 48 hpi using a fluorescent stereomicroscope. Scale bars, 100 μm. E-F. Representative frames extracted from in vivo time-lapse confocal imaging of lyz:dsRed larvae (3 dpf, red neutrophils) injected in the HBV with a (E) low dose or (F) high dose of GFP-S. flexneri M90T. First frame 20 mpi, followed by frames at 3, 7, and 11 hpi. Maximum intensity Z-projection images (2 μm serial optical sections) are shown. Scale bars, 50 μm. See also S2 and S3 Videos.

To visualize the course of infection, larvae were infected with GFP-S. flexneri M90T and imaged by fluorescence microscopy. In agreement with bacterial enumerations, larvae that received a low dose inoculum showed limited proliferation of GFP-S. flexneri (Fig 1D). In contrast, larvae that received a high dose inoculum showed increasing bacterial burdens at 24 and 48 hpi (Fig 1D). Irrespective of the dose used, S. flexneri remained in the HBV and forebrain and did not cause systemic infection. Histological analyses of transverse sections of infected larvae confirmed the aggregation of S. flexneri on walls of the HBV (S1A Fig). In humans, Shigella infection and pathogenesis is strictly dependent upon the type III secretion system (T3SS) [23]. To test the role of the T3SS in our infection model, larvae were injected with T3SS-deficient (T3SS-) S. flexneri (ΔmxiD strain). The survival of zebrafish larvae infected with T3SS- S. flexneri at low or high dose was ~100% (S1B and S1C Fig), demonstrating that the T3SS contributes to Shigella virulence in vivo.

We next used the zebrafish HBV model of infection to study the control of S. flexneri by leukocytes. We outcrossed Tg(mpeg1:Gal4-FF)gl25/Tg(UAS-E1b:nfsB.mCherry)c264 (herein referred to as mpeg1:G/U:mCherry) with Tg(mpx:GFP)i114 (herein referred to as mpx:GFP) to generate double transgenic zebrafish larvae with red macrophages and green neutrophils. Larvae were infected with Crimson-S. flexneri M90T and leukocyte behavior recorded by confocal microscopy. Using a low dose of S. flexneri, we observed rapid aggregation of bacteria on walls of the HBV and by 12 hpi most bacteria had been cleared (S1D Fig, see also S1 Video). Here, macrophages were the first leukocytes to arrive (from 20 mpi) and engulf bacteria, however, as we have previously shown using caudal vein injections, S. flexneri were able to proliferate within macrophages and cause their death [6]. In contrast, neutrophils are massively recruited within hours and become the predominant leukocyte, and actively participate in the control of S. flexneri by engulfing both aggregates of extracellular bacteria and debris from macrophages unable to control infection. We thus infected Tg(lyz:dsRed)nz50 (herein referred to as lyz:dsRed) zebrafish embryos, a transgenic line in which dsRed is expressed specifically in neutrophils [24]. In the case of a low dose, neutrophils are recruited hours following infection and control S. flexneri proliferation (Fig 1E, see also S2 Video). In contrast, a high dose of S. flexneri results in uncontrolled bacterial proliferation and concomitant neutrophil cell death (Fig 1F, see also S3 Video). Collectively, these results demonstrate that infection of the zebrafish HBV is a valuable system to study in vivo the control of Shigella infection by neutrophils.

Sept15 is required to control S. flexneri infection in vivo

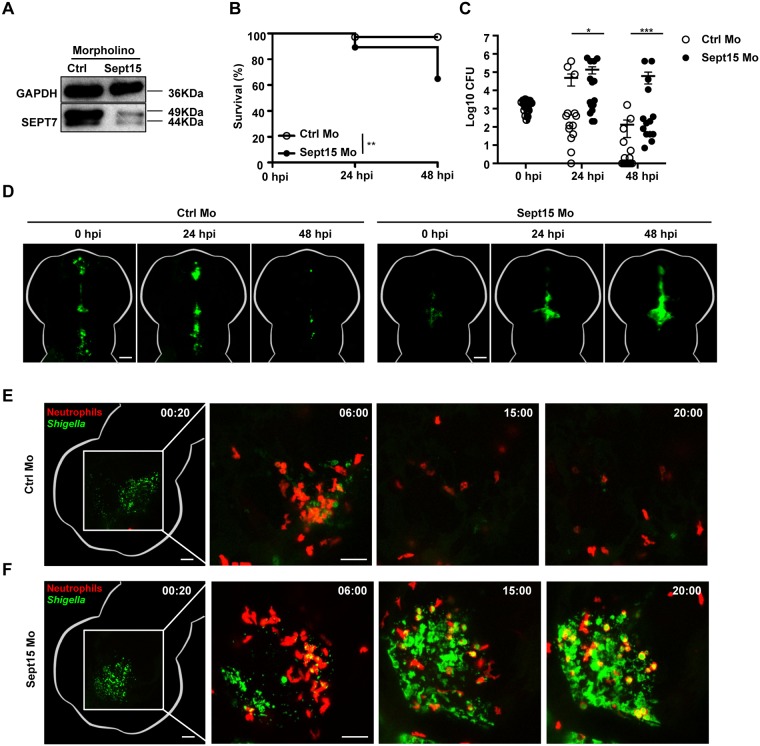

Structural analysis of a human septin complex revealed that SEPT7 is essential for septin filament assembly and function [25]. Zebrafish have orthologs for members of all 4 human septin groups (S1 Table), including Sept15 and Sept7b which share 88.7% and 92.5% identity with human SEPT7, respectively [26]. Confocal microscopy of zebrafish larvae labeled with human anti-SEPT7 antibody shows that Sept15 and/or Sept7b are present in epithelial cells, macrophages, and neutrophils (S2A Fig). To investigate the role of septins in host defence in vivo, zebrafish larvae were injected with control or Sept15 morpholino oligonucleotide and infected with S. flexneri (Fig 2A). As compared to infected control morphants, infected Sept15 morphants present significantly reduced survival and higher bacterial loads (Fig 2B and 2C). Using fluorescent microscopy we observed that in the absence of Sept15 zebrafish larvae failed to clear the infection, showing increasing fluorescence of GFP-Shigella over time (Fig 2D, see also S4 and S5 Videos). In contrast to the ~40% mortality observed for Sept15 morphants infected with wild type S. flexneri, Sept15 morphants infected with avirulent T3SS- S. flexneri present ~100% survival (S2B and S2C Fig). Together, these results show that susceptibility of Sept15 morphants to S. flexneri infection is dependent on the T3SS, and suggest that septins have an important role in the control of S. flexneri infection in vivo. To test if these results are specific to Sept15, we performed experiments using a morpholino oligonucleotide against Sept7b (S2D Fig). Similar to results obtained for Sept15 morphants, Sept7b morphants infected with S. flexneri present significantly reduced survival and higher bacterial loads as compared to infected control morphants (S2E and S2F Fig). To test if the impact of septin depletion is specific to infection of the HBV, Sept15 morphants were systemically infected with S. flexneri via the caudal vein (S2G and S2H Fig). In the case of caudal vein infection, Sept15 morphants present ~40% mortality as compared to control morphants which showed 100% survival.

Fig 2. Sept15 morphants show increased susceptibility to S. flexneri infection.

A. Representative western blot of extracts from larvae injected with control (Ctrl) or Sept15 morpholino (Mo) using antibodies against GAPDH (as control) or SEPT7. B. Survival curves of Ctrl or Sept15 morphants infected with S. flexneri M90T (low dose). Pooled data from 3 independent experiments per treatment using at least 15 larvae per treatment. Significance testing performed by Log Rank test. **, P<0.01. C. Enumeration of bacteria at 0, 24, or 48 hpi from Ctrl (open circles) or Sept15 (closed circles) morphants infected with S. flexneri M90T (low dose). Half-filled circles represent enumerations from larvae at time 0 and are representative of inoculums for both conditions. Pooled data from 3 independent experiments using up to 3 larvae per treatment. Circles represent individual larvae, and only larvae having survived the infection (thus far) included here (i.e., dead larvae not homogenised for counts). Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by Student’s t test. *, P<0.05; ***, P<0.001. D. Representative images of larvae injected with Ctrl or Sept15 Mo and infected in the HBV with GFP-S. flexneri M90T (low dose). For each treatment, the same larva was imaged at 0, 24, and 48 hpi using a fluorescent stereomicroscope. Scale bars, 100 μm. See also S4 and S5 Videos. E-F. Representative frames extracted from in vivo time-lapse confocal imaging of lyz:dsRed larvae (3 dpf, red neutrophils) injected with (E) Ctrl or (F) Sept15 Mo and infected in the HBV with GFP-S. flexneri M90T (low dose). First frame 20 mpi, followed by frames at 6, 15, and 20 hpi. Maximum intensity Z-projection images (2 μm serial optical sections) are shown. Scale bars, 50 μm. See also S6 and S7 Videos.

Neutrophils are crucial to control Shigella infection in vivo [6]. To characterize the ability of Sept15-depleted neutrophils to clear GFP-S. flexneri, we analyzed S. flexneri-neutrophil interactions at the level of the single cell using high-resolution confocal microscopy (Fig 2E and 2F, see also S6 and S7 Videos). In both control and Sept15 morphants, neutrophils are massively recruited to the infection site where they engulf bacteria. Time-lapse movies confirmed that neutrophils from control morphants reliably clear a low dose of GFP-Shigella. In contrast, neutrophils from Sept15 morphants are unable to clear the same dose of Shigella, and are killed upon bacterial challenge.

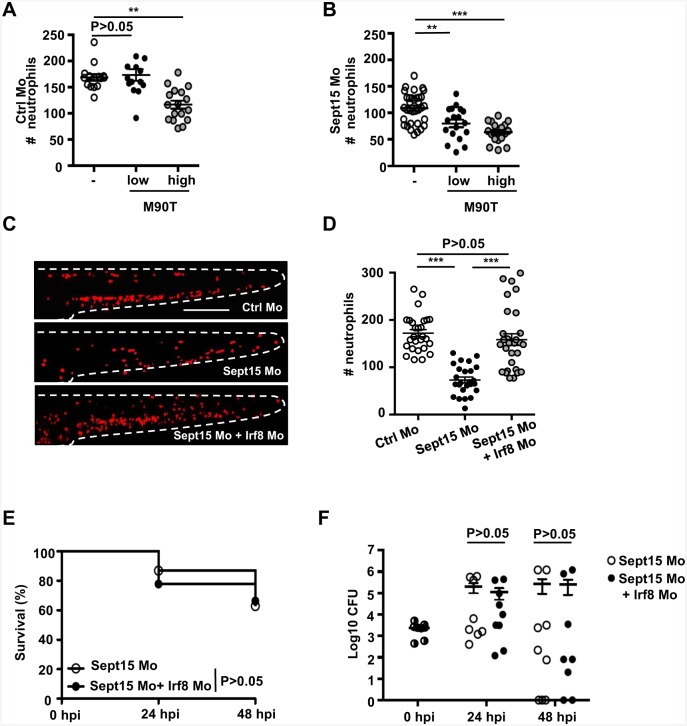

S. flexneri induces neutrophil death in Sept15 morphants

To investigate the fate of neutrophils during infection of Sept15-depleted zebrafish, we used live cell imaging and monitored neutrophils in lyz:dsRed control or Sept15 morphants infected with GFP-S. flexneri. We quantified the total number of neutrophils at the whole animal level in control or Sept15 morphants at 3 dpf. Whereas neutrophil numbers in control morphants infected for 6 h with a low dose of S. flexneri are not significantly different from PBS-injected larvae, larvae infected for 6 h with a high dose of S. flexneri are neutropenic (Fig 3A). Sept15 morphants develop fewer neutrophils than control morphants, and when infected for 6 h with a low or high dose of S. flexneri, neutrophils were reduced even further (Fig 3B). The infection-mediated decrease in neutrophils is dependent on the T3SS, as infection with T3SS- S. flexneri has no effect on neutrophil number in either control or Sept15 morphants (S3A and S3B Fig). To test if increased mortality in Sept15 morphants is a result of neutropenia, we co-injected control or Sept15 morphants with a morpholino oligonucleotide against Irf8 (a gene involved in leukocyte differentiation [27]) to skew the myeloid cell balance towards neutrophils, and infected larvae with S. flexneri (Fig 3C and 3D). Increasing the number of neutrophils is unable to rescue Sept15 morphants from mortality or increasing bacterial burdens, suggesting that susceptibility of Sept15 morphants to S. flexneri is not because of a reduction in neutrophils per se (Fig 3E and 3F). Depletion of macrophages by Irf8 knockdown [27] may also contribute to the susceptibility of Sept15 morphants. Indeed, the ablation of macrophages by exposure of the transgenic line Tg(mpeg1:G/U:mCherry) to metronidazole showed that macrophages provide some protection against high dose S. flexneri infection (S3C and S3D Fig), likely because macrophages are implicated in the initial phagocytosis of Shigella and facilitate neutrophil scavenging crucial for host defence [6].

Fig 3. S. flexneri induces neutrophil death in Sept15 morphants.

A-B. Quantification of neutrophils in lyz:dsRed larvae injected with (A) Ctrl or (B) Sept15 morpholino (Mo), uninfected (open circles) or infected for 6 h with a low (closed circles) or high (grey circles) dose of S. flexneri M90T, from 4 or more larvae per treatment from 3 independent experiments. Circles represent individual larvae. Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest. **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. C. Representative images of lyz:dsRed larvae injected with Ctrl, Sept15, or Sept15 + Irf8 Mo. Scale bar, 250 μm. D. Quantification of neutrophils in lyz:dsRed larvae injected with Ctrl (open circles), Sept15 (closed circles), or Sept15 + Irf8 (grey circles) Mo. Circles represent individual larvae. Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest. ***, P<0.001. E. Survival curves of Sept15 or Sept15 + Irf8 morphants infected with S. flexneri M90T (low dose). Pooled data from 3 independent experiments per treatment using at least 15 larvae per treatment. Significance testing performed by Log Rank test. F. Enumeration of bacteria at 0, 24, or 48 hpi from Sept15 (open circles) or Sept15 + Irf8 (closed circles) morphants infected with S. flexneri M90T (low dose). Half-filled circles represent enumerations from larvae at time 0 and are representative of inocula for both conditions. Pooled data from 3 independent experiments per inoculum class using up to 3 larvae per treatment. Circles represent individual larvae, and only larvae having survived the infection (thus far) included here (i.e., dead larvae not homogenised for counts). Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by Student’s t test.

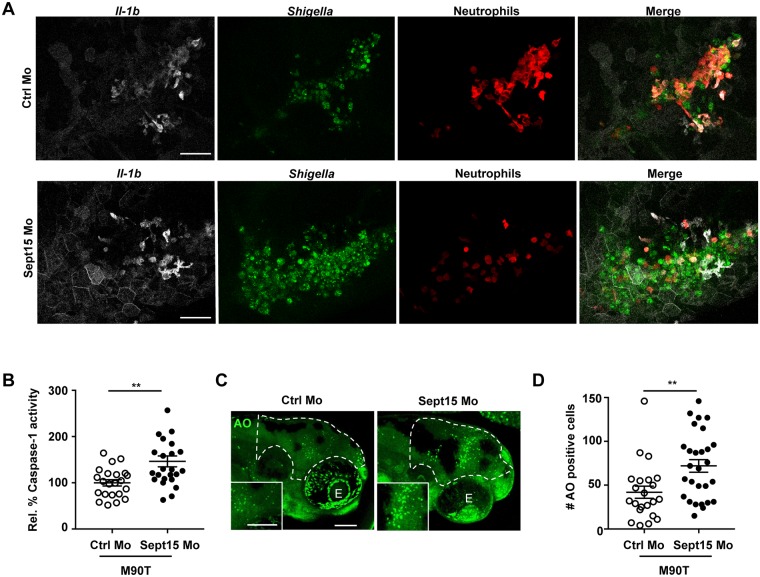

Sept15 restricts the inflammatory response in vivo

S. flexneri is well known to induce inflammation in vitro and in vivo [6, 28, 29]. To identify sources of inflammation in septin-depleted zebrafish larvae, we followed the spatio-temporal dynamics of interleukin 1 beta (il-1b) induction during S. flexneri infection. For this we outcrossed Tg(il-1b:GFP-F)zf550 (herein referred to as il-1b:GFP-F) a transgenic line which expresses farnesylated GFP under control of the il-1b promoter [30], with lyz:dsRed for live cell analysis by confocal microscopy (Fig 4A, see also S8 and S9 Videos). In both control and Sept15 morphants infected with Crimson-S. flexneri, we observed il-1b:GFP-F expression in neutrophils, macrophages, and epithelial cells surrounding the infection site, indicating that leukocytes and other cell types can be a source of il-1b during S. flexneri infection. To understand why Sept15 morphants succumb to S. flexneri infection, we tested Caspase-1 activity (as a readout of Il-1β processing and maturation [31]) in Shigella-infected larvae using FAM-YVAD-FMK, a fluorochrome-labeled inhibitor of Caspase-1 (FLICA) that binds specifically to active Caspase-1 enzyme. Strikingly, Caspase-1 activity is significantly increased in Sept15 morphants compared to control morphants (Fig 4B). Caspase-1-mediated signaling pathways are closely-linked to host cell death [32]. To test whether increased mortality in Sept15-depleted larvae correlates with increased host cell death, we quantified dying cells in the HBV of control and Sept15 morphants infected for 6 h with S. flexneri using acridine orange (AO), a nucleic acid-binding dye which marks dying cells (Fig 4C and 4D). In agreement with increased Caspase-1 activity, we detected a significant increase in numbers of AO-positive cells (1.7 ± 0.3 fold) in S. flexneri-infected Sept15 morphants as compared to control morphants. Together, these results suggest that hyper-inflammation is an underlying factor in the susceptibility of Sept15-deficient larvae to S. flexneri infection.

Fig 4. Sept15 restricts the inflammatory response in vivo.

A. Representative frames extracted from in vivo time-lapse confocal imaging of Tg(il-1b:GFP-F) x Tg(lyz:dsRed) larvae (3 dpf) injected with Ctrl or Sept15 Mo and infected in the HBV with Crimson-S. flexneri M90T (low dose) at 19 hpi. Maximum intensity Z-projection images (2 μm serial optical sections) are shown. Scale bars, 50 μm. See also S8 and S9 Videos. B. Relative % of Caspase-1 activity levels measured in Ctrl and Sept15 morphants infected for 6 h with ~5 x 103 CFU of S. flexneri M90T. Mean±SEM from 3 independent experiments per treatment using 5–10 larvae per experimental group. Significance testing performed by Student’s t test. **; P<0.01. C. Representative images of Ctrl and Sept15 morphants (Mo) infected with S. flexneri M90T in the HBV and stained for acridine orange. Dotted line shows the area where cells were quantified (i.e. the infected HBV). Scale bars, 100 μm. E, eye. D. Number of acridine orange (AO) positive cells counted in the HBV of Ctrl or Sept15 morphants 6 hpi with S. flexneri M90T. Significance testing performed by Student’s t test. **, P<0.001. Pooled data from 3 independent experiments per treatment using at least 6 larvae per treatment.

Previous work has shown that overexpression of leukotriene A4 hydrolase (lta4h) generates inflammation due to induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha (tnf-a), making zebrafish more susceptible to infection by Mycobacterium marinum [33]. To distinguish between tnf-a and il-1b inflammatory pathways in host defence against S. flexneri, we overexpressed lta4h in zebrafish larvae (S4 Fig). Overexpression of lta4h significantly increased transcript levels of tnf-a without affecting levels of il-1b (S4A and S4B Fig). However, the upregulation of tnf-a failed to increase susceptibility to a low dose of S. flexneri infection (S4C and S4D Fig), strongly suggesting that increased susceptibility of Sept15 morphants to S. flexneri infection is dependent on the activation of an il-1b signaling cascade.

Reduction of inflammation by anakinra rescues Sept15-deficiency in vivo

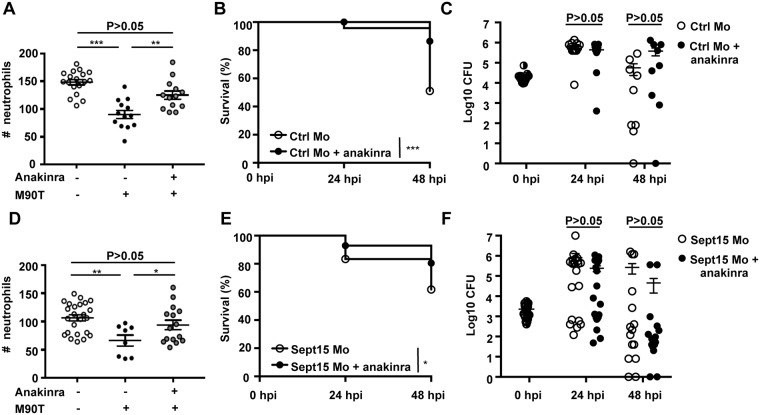

Anakinra is an antagonist of IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) used to prevent inflammatory shock, sepsis, and auto-inflammatory syndromes in humans [34, 35]. Anakinra is an analogue of human IL-1RA (interleukin 1 receptor antagonist), an endogenous inhibitor of IL-1 that binds competitively to the IL-1 receptor. Although an endogenous Il-1β receptor antagonist has not been reported in fish, anakinra presents comparable homology to both human and zebrafish IL-1β (31.0% and 29.7% respectively). We tested the ability of anakinra to reduce inflammation and increase protection in our S. flexneri-zebrafish infection model. Treatment with anakinra rescued the survival of neutrophils and larvae infected with a high dose of S. flexneri (Fig 5A and 5B), without significantly affecting the enumerations of bacterial burden quantified from viable larvae (Fig 5C).

Fig 5. Anakinra therapy protects neutrophils and enhances host survival upon S. flexneri infection.

A. Quantification of neutrophils in lyz:dsRed larvae injected with Ctrl morpholino, uninfected (open circles) or infected for 6 h with a high dose of S. flexneri M90T (closed circles) and treated with anakinra (grey circles), from 3 independent experiments using up to 5 larvae per treatment. Circles represent individual larvae. Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest. ***, P<0.001. B. Survival curves of Ctrl morphants infected with S. flexneri M90T (high dose), untreated (open circles) or treated with anakinra (closed circles). Pooled data from 4 independent experiments per treatment using at least 15 larvae per experiment. Significance testing performed by Log Rank test. **, P<0.01. C. Enumeration of bacteria at 0, 24, or 48 hpi from Ctrl morphants infected with S. flexneri M90T (high dose), untreated (open circles) or treated with anakinra (closed circles). Half-filled circles represent enumerations from larvae at time 0 and are representative of inoculums for both conditions. Pooled data from 4 independent experiments per inoculum class using up to 3 larvae per treatment. Circles represent individual larvae, and only larvae having survived the infection (thus far) included here (i.e., dead larvae not homogenised for counts). Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by Student’s t test. D. Quantification of neutrophils in lyz:dsRed larvae injected with Sept15 Mo, uninfected (open circles) or infected for 6 h with a low dose of S. flexneri M90T (closed circles) and treated with anakinra (grey circles), from 3 independent experiments using up to 3 larvae per treatment. Circles represent individual larvae. Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest. **, P<0.01. E. Survival curves of Sept15 morphants infected with S. flexneri M90T (low dose), untreated (open circles) or treated with anakinra (closed circles). Pooled data from 5 independent experiments per treatment using at least 15 larvae per experiment. Significance testing performed by Log Rank test. **, P<0.01. F. Enumeration of bacteria at 0, 24, or 48 hpi from Sept15 morphants infected with S. flexneri M90T (low dose), untreated (open circles) or treated with anakinra (closed circles). Half-filled circles represent enumerations from larvae at time 0 and are representative of inoculums for both conditions. Pooled data from 7 independent experiments per treatment using up to 3 larvae per experiment. Circles represent individual larvae, and only larvae having survived the infection (thus far) included here (i.e., dead larvae not homogenised for counts). Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by Student’s t test.

We next tested the protective effect of anakinra in Sept15 morphants. In the absence of infection, neutrophil numbers do not differ between control and anakinra-treated morphants (S5A Fig). Remarkably, upon Shigella infection, anakinra prevented neutrophil death and significantly reduced the mortality of infected Sept15 morphants (Fig 5D and 5E), without significantly affecting enumerations of bacterial burden quantified from viable larvae (Fig 5F). Collectively, these results show that reduction of inflammation by therapy can promote neutrophil and zebrafish survival during S. flexneri infection, and rescue septin-deficiency in vivo.

Discussion

The zebrafish is a powerful non-mammalian vertebrate model to study the innate immune response to bacterial infection [36, 37]. We have previously used Shigella infection of the zebrafish caudal vein to study bacterial autophagy in vivo [6]. Here, using Shigella infection of the zebrafish HBV, we reveal that septins have a crucial role in restricting inflammation in vivo. Strikingly, anakinra is able to counteract septin-deficiency by preventing neutrophil death and reducing zebrafish mortality upon S. flexneri infection. These findings reveal a novel role for septins in inflammation control and host defence.

The zebrafish HBV has been used to model infection by other bacterial pathogens including Listeria monocytogenes [38], Salmonella Typhimurium [39], Pseudomonas aeruginosa [40, 41], and M. marinum [42]. In the case of L. monocytogenes, bacteria in the HBV disseminate 2–3 dpi, spreading infection to the trunk and tail muscle. Although S. flexneri is well known for invasion and inflammatory destruction of the human intestinal epithelium, and similarly to L. monocytogenes has the ability to form actin tails and spread from cell-to-cell [43], we did not observe S. flexneri dissemination outside of the zebrafish HBV or forebrain ventricle. This allowed us to analyze S. flexneri-neutrophil interactions in a compartmentalized environment, where we observed that recruited neutrophils efficiently engulf and eliminate a low dose of S. flexneri. This neutrophil behavior is in stark contrast to HBV infections of non-pathogenic E. coli, where neutrophils poorly engulf fluid-borne bacteria [44]. These observations are likely a result of S. flexneri virulence factors which promote bacterial recognition and engulfment by neutrophils.

The rabbit ileal loop model is commonly used to study the host response to Shigella infection [28]. Recently, a mouse model of shigellosis by intraperitoneal infection has been described [29]. In both animal models, S. flexneri induces the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and TNF-α, as observed in humans suffering from shigellosis [45]. However, mammalian models remain poorly suited to spatio-temporally examine the innate immune response to Shigella in vivo. By contrast, the natural translucency of zebrafish larvae enables non-invasive in vivo imaging at high resolution throughout the organism. We show that il-1b:GFP-F larvae can be used to visualize the spatio-temporal dynamics of il-1b during S. flexneri infection. In-depth investigation of infection by Shigella and other bacteria that induce inflammatory signals, including L. monocytogenes and S. Typhimurium, will help to describe more precisely the coordination between septin assembly and inflammation.

When applied as a model of vertebrate development, the zebrafish has been key in linking Sept9a and Sept9b to growth defects in vivo [46]. In support of a highly conserved role for septins amongst vertebrates, the depletion of Sept15 induces cell differentiation and division defects in the pancreatic endocrine cells of zebrafish larvae [47]. More recently, the zebrafish has been used to highlight the central role of Sept15 in actin-based myofibril and cardiac function [48]. Septins are known components of the ciliary diffusion barrier in humans, and zebrafish Sept6 and Sept15 morphants present phenotypes resembling human ciliopathies, highlighting translatability of the zebrafish as a model for the study of septin biology in vivo [26, 49]. Here, we report defects in innate immunity that derive from Sept15 depletion, including inflammation and neutropenia, and show that inflammation increases the susceptibility of neutrophils to S. flexneri infection. The mechanisms underlying cell death by Shigella in epithelial cells [50] and macrophages (including apoptosis [51], necrosis [52], pyroptosis [53], and pyronecrosis [54]), have been the subject of intense investigation. The zebrafish can represent a unique experimental system to investigate Shigella-neutrophil interactions and dissect the molecular features underlying Shigella-mediated host cell death in vivo. Moreover, it is envisioned that insights into neutrophil biology arising from our S. flexneri-zebrafish model can enable novel therapeutic approaches towards diseases with an important neutrophil component.

The dysregulation of IL-1β is associated with a wide variety of inflammatory diseases [55]. Intervention into this pro-inflammatory pathway, either by blocking IL-1R or by preventing the processing / secretion of IL-1β, is critical for treatment [34]. For example, anakinra has been used to reduce IL-1β levels in a mouse model of chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), an immunodeficiency characterized by defective production of ROS [56]. Anakinra has also been effective in treatment of human patients with Schnitzler syndrome (an autoimmune disorder) or with mutations in cold-induced autoinflammatory syndrome 1 gene (CIAS1) [57]. Results obtained from our S. flexneri-zebrafish HBV infection model show that septins play a key role in the restriction of inflammation and neutrophil clearance of S. flexneri. Other studies performed in zebrafish have identified a role for the inflammasome in leukocyte clearance of L. monocytogenes and S. Typhimurium [58, 59]. What is the precise role of septins in inflammation? Septins are a unique component of the cytoskeleton that associate with cellular membranes, actin filaments, and microtubules [1]. Previous work has described a role for the actin cytoskeleton in inflammation control, by regulating the NLRP3 and pyrin inflammasomes [10–14]. We hypothesize that septins interact with components of the inflammasome and regulate assembly of this multiprotein complex. Although a precise role for septins in the assembly and activity of the inflammasome awaits investigation, these results add weight to previous studies linking inflammation and the cytoskeleton, and suggest that targeting the cytoskeleton can represent an important anti-inflammatory strategy. It is increasingly recognized that interactions between inflammation and the cytoskeleton play important roles in determining disease outcome. It will now be of great interest to further study the link between septins and inflammation, and pursue components of the cytoskeleton as novel molecular targets for inhibition of inflammation.

Material and methods

Ethics statement

Animal experiments were performed according to the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and approved by the Home Office (Project license: PPL 70/7446).

Zebrafish care and maintenance

Wild type AB were purchased from the Zebrafish International Resource Center (Eugene, OR). Tg(mpeg1:Gal4-FF)gl25/Tg(UAS-E1b:nfsB.mCherry)c264, Tg(lyz:dsRed)nz50, Tg(mpx:GFP)i114, Tg(mpeg1:YFP)w200 and Tg(il-1b:GFP-F)zf550 transgenic zebrafish lines are described previously [24, 30, 60–62]. Eggs were obtained by natural spawning and reared in Petri dishes containing 0.5x E2 water supplemented with 0.3 μg/ml methylene blue (embryo medium) [63]. For microscopy, embryo medium was supplemented with 0.003% 1-phenyl-2-thiourea (Sigma-Aldrich) from 1 dpf to prevent melanization. Both embryos and infected larvae were reared at 28.5°C. All timings in the text refer to the developmental stage at the reference temperature of 28.5°C [64]. Larvae were anesthetized with 200 μg/ml tricaine (Sigma-Aldrich) in embryo medium for injections and during in vivo imaging.

Zebrafish bacterial infections

Bacterial strains used in this study were wildtype invasive S. flexneri serotype 5a M90T expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP), mCherry, or Crimson (GFP-S. flexneri, mCherry-S. flexneri, or Crimson-S. flexneri respectively) and T3SS− non-invasive variant (ΔmxiD) expressing mCherry [6]. S. flexneri were cultured overnight in trypticase soy broth, diluted 80x in fresh trypticase soy broth, and cultured until A600nm = 0.6. For injection of zebrafish larvae, bacteria were recovered by centrifugation, washed and reconstituted at the desired concentration in PBS with 0.1% phenol red. At 3 dpf, zebrafish larvae were microinjected in the HBV with up to 1 nl bacterial suspension as described previously [65]. A low dose was defined as 0.5–3.0 x 103 CFU; a high dose was defined as 1.0–2.2 x 104 CFU. Inoculums were checked a posteriori by injecting into PBS and plating onto Luria Broth (LB) agar. Larvae were maintained in individual wells of 24-well culture dishes containing embryo medium.

Measurement of bacterial burden

At indicated time points, larvae were sacrificed with tricaine, lysed in PBS with 0.4% Triton X-100 and homogenized. Serial dilutions of homogenates were plated onto LB agar supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic and CFU enumerated after 24 h incubation at 37°C; only fluorescent colonies were scored. Only viable larvae were used for CFU enumerations.

Morpholino and RNA injections

Antisense morpholino oligonucleotides were obtained from GeneTools (www.gene-tools.com). Morpholino sequence 5’-ACTCACCTTAAACAGGAAAGCAAGC-3’ was designed to target zebrafish Sept15 (ENSDARG00000102889). Morpholino sequence 5’-GAAACATCTTCACTTCGTACCTGAA-3’ was designed to target zebrafish Sept7b (ENSDARG00000052673). A standard morpholino sequence with no known target in the zebrafish genome was used as a control [6]. To increase neutrophil numbers, embryos were injected with Irf8 splice blocking morpholino as previously described [27]. Morpholinos were diluted to the desired final concentrations (0.5 mM for Sept7b and Sept15 morpholinos, 1mM for Irf8 morpholino) in 0.1% phenol red solution (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.8 nl/embryo injected. For Leukotriene A4 hydrolase (lta4h) overexpression experiments, 1.2 nl of 200 ng/μl RNA was injected, as previously described [33]. Morpholino and RNA injections were performed on 1–8 cell stage embryos.

Live imaging, image processing, and analysis

Whole-animal in vivo imaging was performed on anaesthetized zebrafish larvae immobilized in 1% low melting point agarose in 60 mm Petri dishes as previously described [65]. Transmission and fluorescence microscopy was done using a Leica M205FA fluorescent stereomicroscope. Imaging was performed with a 10x (NA 0.5) dry objective. Multiple-field Z-stacks were acquired every 15 min for experiments involving neutrophil recruitment to HBV infection. For high resolution confocal microscopy, infected larvae were positioned in 35 mm glass-bottom dishes and immobilized in 1% low melting agarose as described in [65]. Confocal microscopy was performed using Zeiss LSM 710, Leica SPE, or Leica SP8 microscopes and 10x, 20x, 40x oil, or 63x oil immersion objectives. For time-course acquisitions, larvae were maintained at 28.5°C. AVI/MOV files were processed and annotated using ImageJ/FIJI software.

Histologic sections

Zebrafish larvae were infected with S. flexneri in the HBV at 3 dpf. At 6 hpi, embryos were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Embryos were washed 3 times in PBS and mounted in 1% agarose. The agarose was dehydrated in a series of ethanol from 70 to 100% and then in 100% xylene and embedded in paraffin. Transversal sections of the head were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). H&E-stained tissues were imaged with an Axio Lab.A1 microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Germany) and images acquired using an Axio Cam ERc5s colour camera. Images were processed using AxioVision (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Germany).

qRT-PCR

Total RNA from 5 snap-frozen larvae was extracted using RNAqueous Kit (Ambion). cDNA was obtained using QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen). Primers for il-1b and tnf-a were previously described [66]. For each experiment, quantitative PCR was performed in technical duplicate using a Rotor-GeneQ (Qiagen) thermocycler and SYBR green reaction power mix (Applied Biosystems). To normalize cDNA amounts, we used the housekeeping gene ef1a1l1 [6] and the 2-ΔΔCT method [67].

Caspase-1 activity and cell death detection

Caspase-1 activity was determined using a FAM-FLICA Caspase-1 Assay Kit (ImmunoChemistry Technologies) as described previously [68]. Briefly, a 150x stock solution of FAM-YVAD-FMK was prepared according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. The stock was diluted to 1x in embryo medium and 5–10 larvae per experimental group bathed in the staining solution from 4.5 hpi to 6 hpi at 28.5°C. For cell death detection, larvae were bathed at 6 hpi in 2 μg/ml Acridine Orange in embryo medium for 30 min. Larvae were washed 3 times in embryo medium prior to imaging by confocal microscopy.

Whole-mount immunostaining

Wholemount immunostaining of zebrafish was performed using a standard protocol [65]. To detect septins in neutrophils and macrophages, Tg(mpx:GFP)i114 and Tg(mpeg1:YFP)w200 larvae were labelled with human anti-SEPT7 antibody (IBL), respectively.

Immunoblotting

To extract zebrafish proteins, 5–8 larvae were lysed in lysis buffer (1 M Tris, 5 M NaCl, 0.5 M EDTA, 0.01% Triton X-100) and homogenized with pestles. After centrifugation at 4°C for 15 min, supernatants were run on 8% acrylamide gels. Extracts were blotted with anti-SEPT7 (IBL) or anti-GAPDH (GeneTex) as a loading control.

Drug treatments

Macrophages were ablated by exposure of Tg(mpeg1:Gal4-FF)gl25/Tg(UAS-E1b:nfsB.mCherry)c264 larvae to metronidazole (10 mM, Sigma-Aldrich) in embryo medium supplemented with 1% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich). Metronidazole was administered at 2 dpf for 24 h and larvae washed 3 times prior to infection. For anakinra experiments, the embryo medium was supplemented with anakinra (10 μM, Kineret) from 1 dpf and refreshed daily until completion of the assay at 48 hpi.

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using Log Rank test (survival curves), unpaired two-tail Student’s t test (on log10 values of CFU counts, and log2 gene expression data), or ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest as specified in the figure legends (neutrophil counts, Caspase-1 activity) using Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc). Data were considered significant when P<0.05 (*), P<0.01 (**), or P<0.001 (***).

Supporting information

A. Transverse section of larvae (3 dpf) infected in the HBV with S. flexneri M90T (low dose) for 6h. Arrow indicates the localisation of the bacteria inside the ventricle. Scale bar, 50 μm. E, eye; M, midbrain ventricle. B. Survival curves of larvae infected with low (≤ 3 x 103 CFU) or high (≥ 1 x 104 CFU) inoculum of T3SS- S. flexneri (ΔmxiD strain) using at least 15 larvae per experiment. Significance testing performed by Log Rank test. C. Enumeration of bacteria at 0, 24, or 48 hpi from larvae infected with low (open circles) or high (closed circles) dose of S. flexneri M90T using up to 3 larvae per treatment. Circles represent individual larvae. Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by Student’s t test. **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. Note bacterial load does not significantly decrease in highly infected fish because of the high bacteria:leukocyte ratio and thus more time is required to clear the bacterial burden. D. Frames extracted from in vivo time-lapse confocal imaging of mpeg1:G/U:mCherry x mpx:GFP larvae (3 dpf) injected in the HBV with low dose of Crimson-S. flexneri. First frame 20 mpi, followed by frames at 1, 3, and 12 hpi. Maximum intensity Z-projection images (2 μm serial optical sections) are shown. Scale bars, 50 μm. See also S1 Video.

(TIF)

A. Immunostaining of zebrafish larvae at 3 dpf with antibody against SEPT7 (red) in cells of the caudal fin epithelium (a), a neutrophil (mpx:GFP labeled) (b), and a macrophage (mpeg1:YFP labeled) (c). Scale bars, 10 μm. B. Survival curves of Ctrl or Sept15 morphants infected with T3SS- S. flexneri (ΔmxiD strain, low dose). Pooled data from 3 independent experiments per treatment using at least 15 larvae per experiment. Significance testing performed by Log Rank test. C. Enumeration of bacteria at 0, 24, or 48 hpi from Ctrl (open circles) or Sept15 (closed circles) morphants infected with T3SS- S. flexneri (ΔmxiD strain). Circles represent individual larvae, and only larvae having survived the infection (thus far) included here (i.e., dead larvae not homogenised for counts). Half-filled circles represent enumerations from larvae at time 0 and are representative of inoculums for both conditions. Pooled data from 3 independent experiments using up to 3 larvae per treatment. Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by Student’s t test. D. Representative western blot of extracts from larvae injected with Ctrl or Sept7b morpholino (Mo) using antibodies against GAPDH (as control) or SEPT7. E. Survival curves of Ctrl or Sept7b morphants infected in the HBV with S. flexneri M90T (low dose). Pooled data from 3 independent experiments per treatment using at least 15 larvae per treatment. Significance testing performed by Log Rank test. ***, P<0.001. F. Enumeration of bacteria at 0, 24, or 48 hpi from Ctrl (open circles) or Sept7b (closed circles) morphants infected with S. flexneri M90T (low dose). Half-filled circles represent enumerations from larvae at time 0 and are representative of inoculums for both conditions. Pooled data from 3 independent experiments using up to 3 larvae per treatment. Circles represent individual larvae, and only larvae having survived the infection (thus far) included here (i.e. dead larvae not homogenised for counts). Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by Student’s t test. *, P<0.05. G. Survival curves of Ctrl or Sept15 morphants infected in the caudal vein with S. flexneri M90T (low dose). Pooled data from 3 or more independent experiments per treatment using at least 15 larvae per experiment. Significance testing performed by Log Rank test. **, P<0.01. H. Enumeration of bacteria at 0, 24, or 48 hpi from Ctrl (open circles) or Sept15 (closed circles) morphants infected with S. flexneri M90T in the caudal vein. Circles represent individual larvae, and only larvae having survived the infection (thus far) included here (i.e., dead larvae not homogenised for counts). Half-filled circles represent enumerations from larvae at time 0 and are representative of inoculums for both conditions. Pooled data from 3 independent experiments using up to 3 larvae per treatment. Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by Student’s t test. **, P<0.01.

(TIF)

A-B. Quantification of neutrophils in lyz:dsRed larvae injected with (A) Ctrl or (B) Sept15 morpholino (Mo), uninfected (open circles) or infected for 6 h with a low (closed circles) or high (closed squares) dose of T3SS- S. flexneri (ΔmxiD strain), from 4 or more larvae per treatment from 2 independent experiments. Circles represent individual larvae. Significance testing performed by ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest. C. Survival curves of Ctrl or macrophage ablated (metronidazole treated Tg(mpeg1:Gal4-FF)/Tg(UAS-E1b:nfsB.mCherry)) larvae infected in the HBV with S. flexneri M90T (low dose). Pooled data from 3 independent experiments per treatment using at least 15 larvae per treatment. Significance testing performed by Log Rank test. ***, P<0.001. D. Enumeration of bacteria at 0, 24, or 48 hpi from Ctrl (open circles) or macrophage ablated (closed circles) larvae infected with S. flexneri M90T (low dose). Half-filled circles represent enumerations from larvae at time 0 and are representative of inoculums for both conditions. Pooled data from 3 independent experiments using up to 3 larvae per treatment. Circles represent individual larvae, and only larvae having survived the infection (thus far) included here (i.e., dead larvae not homogenised for counts). Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by Student’s t test.

(TIF)

A-B. Relative expression of tnf-a and il1-b in larvae injected with lta4h RNA (lta4h high). Mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments per treatment using at least 5 larvae per experiment. Significance testing performed by Student’s t test. *, P<0.05. C. Survival curves of control and lta4h high larvae infected with S. flexneri M90T (low dose). Pooled data from 3 independent experiments per treatment using at least 15 larvae per treatment. Significance testing performed by Log Rank test. D. Enumeration of bacteria at 0, 24, or 48 hpi from Ctrl (open circles) or lta4h high (closed circles) larvae infected with S. flexneri M90T (low dose). Half-filled circles represent enumerations from larvae at time 0 and are representative of inocula for both conditions. Pooled data from 3 independent experiments per inoculum class using up to 3 larvae per treatment. Circles represent individual larvae, and only larvae having survived the infection (thus far) included here (i.e., dead larvae not homogenised for counts). Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by Student’s t test.

(TIF)

A. Quantification of neutrophils in lyz:dsRed larvae injected with Sept15 morpholino, untreated (open circles) or treated with anakinra (grey circles), from 3 independent experiments using up to 5 larvae per treatment. Control values also represented in Fig 5D. Circles and squares represent individual larvae. Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest.

(TIF)

Zebrafish septins were determined using the Ensembl database (ensembl.org), by searching the zebrafish genome assembly (version GRCz10) for proteins containing the septin-type guanine nucleotide-binding (G) domain (IPR030379). The closest human homologs were identified by BLAST of individual protein sequences to UNIPROT database (www.uniprot.org). When multiple isoforms of zebrafish septins are reported in Ensembl, the one referenced in RefSeq (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/) is reported here and adopted for protein search. In cases of multiple isoforms referenced in RefSeq, we selected the principal isoform according to annotations reported by Ensembl (APPRIS annotations, http://appris.bioinfo.cnio.es). % identity represents the identity of individual zebrafish septins to the canonical isoform of the closest human septin. Position of the septin-type G-domain was predicted using http://prosite.expasy.org. * partial sequence; ** Incomplete septin-type G-domain.

(TIF)

Double transgenic mpeg1:G/U:mCherry x mpx:GFP zebrafish larva infected at 3 dpf in the HBV with a low dose of Crimson-S. flexneri M90T and live imaged at confocal microscope every 1 min 30 sec from 20 mpi (t = 0 on the movie) until 16 hpi (t = 15 h 45 min on the movie). At the beginning of the acquisition few macrophages (mCherry+ cells) have already been recruited to the injected S. flexneri (white). Note the macrophage full of bacteria (mCherry+ cell full of white bacteria). At t = 1 h 36 min on the movie, this macrophage rounds up, dies, and is rapidly engulfed by neutrophils (GFP+ cells). Neutrophils are recruited to the injected bacteria from 1 hpi, they accumulate progressively in the HBV interacting with the injected bacteria. Note that the bacteria cluster and aggregate on the walls of the ventricle where they are engulfed by neutrophils. Maximum intensity projection (2 μm Z serial sections) is shown.

(MOV)

lyz:dsRed zebrafish larva infected at 3 dpf in the HBV with a low dose of GFP-S. flexneri M90T and live imaged every 1 min from 20 mpi (t = 0 on the movie) to 20 hpi (t = 19 h 30 min on the movie) using confocal microscopy. Neutrophils are recruited to the bacteria and efficiently engulf them as they cluster and aggregate on the walls of the ventricle. Note that neutrophils act as a swarm in engulfing the bacteria. Maximum intensity projection (2 μm serial Z sections) is shown.

(MOV)

lyz:dsRed zebrafish larva infected at 3 dpf in the HBV with a high dose of GFP-S. flexneri M90T and imaged every 1 min 31 sec from 20 mpi to 20 hpi using confocal microscopy. Neutrophils (dsRed+ cells) are recruited to the bacteria from 1 hpi and engulf them. By 3 h 30 mpi (3 h 00 min on the movie), neutrophils fail to eliminate the engulfed bacteria and start to die, presumably killed by S. flexneri over time. Note the accumulation of green bacteria inside dsRed+ neutrophils, and eventual death of the larvae. Maximum intensity projection (2 μm serial Z optical sections) is shown.

(MOV)

lyz:dsRed zebrafish embryos were injected with Ctrl morpholino and infected at 3 dpf in the HBV with a low dose of GFP-S. flexneri M90T, and imaged every 15 min for 45 h using fluorescent stereomicroscopy.

(MOV)

lyz:dsRed zebrafish embryos were injected with Sept15 morpholino and infected at 3 dpf in the HBV with a low dose of GFP-S. flexneri M90T, and imaged every 15 min for 45 h using fluorescent stereomicroscopy.

(MOV)

lyz:dsRed zebrafish embryos were injected with Ctrl morpholino and infected at 3 dpf in the HBV with a low dose of GFP-S. flexneri M90T and live imaged every 2 min from 20 mpi (t = 0 on the movie) to 20 h 30 mpi (t = 20 h on the movie) using confocal microscopy. As shown in S2 Video, neutrophils (dsRed+ cells) are recruited to the HBV by 1 hpi where they interact with GFP S. flexneri clustered and aggregated along the HBV wall. Neutrophils progressively engulf and eliminate S. flexneri, as well as dying infected macrophages (dsRed- GFP+ cells). Maximum intensity projection (2μm serial Z optical sections) is shown.

(MOV)

lyz:dsRed zebrafish embryos were injected with Sept15 morpholino and infected at 3 dpf in the HBV with a low dose of GFP-S. flexneri M90T and imaged every 2 min from 20 mpi (t = 0 on the movie) to 20 h 30 mpi (t = 20 h on the movie) using confocal microscopy. S6 and S7 Videos were acquired at the same time. Note that at the beginning of this movie, neutrophil behaviour from Sept15 morphant is similar to that of Ctrl morphant: neutrophils are recruited by 1 hpi and interact with S. flexneri, and engulf the bacteria and dying macrophages (dsRed- GFP+ cells). However, by 6 hpi neutrophils fail to control the infection (fail to engulf bacteria, fail to engulf dying macrophages) concomitant with massive proliferation of the bacteria. Maximum intensity projection (2μm serial Z optical sections) is shown.

(MOV)

Double transgenic Tg(il-1b:GFP-F) x Tg(lyz:dsRed) zebrafish embryos injected with Ctrl morpholino and infected at 3 dpf in the HBV with a low dose of Crimson-S. flexneri M90T (labelled green in the movie) and imaged every 3 min from 20 mpi to 20 h 20 mpi using confocal microscopy. Neutrophil (dsRed+ cells) are recruited to the injected bacteria. il-1b:GFP expressing cells (labelled white in the movie) start to appear from 3h 30 mpi. Cells which are il-1b+ (membrane) and dsRed- are presumably macrophages. Cells which are il-1b+ (membrane) and dsRed+ (cytoplasmic) are presumably neutrophils. At the end of the acquisition bacteria have been engulfed by leukocytes and the infection is controlled. Maximum intensity projection (2μm serial Z optical sections) is shown.

(MOV)

Double transgenic Tg(il-1b:GFP-F) x Tg(lyz:dsRed) zebrafish embryos were injected with Sept15 morpholino and infected at 3 dpf in the HBV with a low dose of Crimson-S. flexneri M90T (labelled green in the movie) and imaged every 3 min from 20 mpi to 20 h 20 mpi using confocal microscopy. S8 and S9 Videos were acquired at the same time. Neutrophils (dsRed+ cells) are recruited to the injected bacteria. However Sept15 morphants progressively fail to control S. flexneri, and neutrophils die concomitant with bacterial proliferation. The first il-1b producing cells (here labelled in white) are leukocytes observed from 3 hpi. Strikingly, in contrast to Ctrl morphants, Sept15 morphants show increasing il-1b induction in neutrophils, macrophages, and epithelial cells surrounding the infection site. Maximum intensity projection (2μm serial Z optical sections) is shown.

(MOV)

Acknowledgments

We thank Philip Elks, Stephen Renshaw, Philippe Herbomel, Jean-Pierre Levraud, and Georges Luftalla for zebrafish lines and helpful discussions. We thank Francisco J. Roca and Lalita Ramakrishnan for lta4h mRNA, and François-Xavier Campbell-Valois and Philippe Sansonetti for Shigella tools. We thank all members of the Mostowy lab, and in particular Nagisa Yoshida, Mäelle Bruneau, Niall Corry, and Aurélie Deleforge for experimental help.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

ARW is supported by a Medical Research Council PhD studentship. VT is supported by a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship (H2020-MSCA-IF-2015 – 700088). Work in the Mostowy laboratory is supported by a Wellcome Trust Research Career Development Fellowship (WT097411MA) and the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Mostowy S, Cossart P. Septins: the fourth component of the cytoskeleton. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(3):183–94. doi: 10.1038/nrm3284 . Epub 2012/02/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saarikangas J, Barral Y. The emerging functions of septins in metazoans. EMBO Rep. 2011;(11):1118–26. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.193 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mostowy S, Bonazzi M, Hamon MA, Tham TN, Mallet A, Lelek M, et al. Entrapment of intracytosolic bacteria by septin cage-like structures. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8(5):433–44. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.10.009 . Epub 2010/11/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sirianni A, Krokowski S, Lobato-Márquez D, Buranyi S, Pfanzelter J, Galea D, et al. Mitochondria mediate septin cage assembly to promote autophagy of Shigella. EMBO Rep. 2016. doi: 10.15252/embr.201541832 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mostowy S, Shenoy AR. The cytoskeleton in cell-autonomous immunity: structural determinants of host defence. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15 doi: 10.1038/nri3877 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mostowy S, Boucontet L, Mazon Moya MJ, Sirianni A, Boudinot P, Hollinshead M, et al. The zebrafish as a new model for the in vivo study of Shigella flexneri interaction with phagocytes and bacterial autophagy. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(9):e1003588 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003588 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10(2):417–26. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He Y, Hara H, Nunez G. Mechanism and regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.09.002 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma D, Kanneganti TD. The cell biology of inflammasomes: Mechanisms of inflammasome activation and regulation. J Cell Biol. 2016;213(6):617–29. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201602089 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. Dynamics of macrophage polarization reveal new mechanism to inhibit IL-1β release through pyrophosphates. EMBO. 2009. (14):2114–27. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.163 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin J, Yu Q, Han C, Hu X, Xu S, Wang Q, et al. LRRFIP2 negatively regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages by promoting Flightless-I-mediated caspase-1 inhibition. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2075 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3075 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson KE, Chikoti L, Chandran B. Herpes simplex virus 1 infection induces activation and subsequent inhibition of the IFI16 and NLRP3 inflammasomes. Journal of virology. 2013;87(9):5005–18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00082-13 . 3624293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim ML, Chae JJ, Park YH, De Nardo D, Stirzaker RA, Ko H-J, et al. Aberrant actin depolymerization triggers the pyrin inflammasome and autoinflammatory disease that is dependent on IL-18, not IL-1β. J Exp Med. 2015;212(6):927–38. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Standing AS, Malinova D, Hong Y, Record J, Moulding D, Blundell MP, et al. Autoinflammatory periodic fever, immunodeficiency, and thrombocytopenia (PFIT) caused by mutation in actin-regulatory gene WDR1. J Exp Med. 2017;214(1):59–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161228 . Epub 2016/12/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Misawa T, Takahama M, Kozaki T, Lee H, Zou J, Saitoh T, et al. Microtubule-driven spatial arrangement of mitochondria promotes activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(5):454–60. doi: 10.1038/ni.2550 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dos Santos G, Rogel MR, Baker MA, Troken JR, Urich D, Morales-Nebreda L, et al. Vimentin regulates activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6574 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7574 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lima IFN, Havt A, Lima AAM. Update on molecular epidemiology of Shigella infection. Curr Opin Gastroent. 2015;31(1):30–7. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000136 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrington R. Drug-resistant stomach bug. Scientific American. 2015;313(2):88 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Carneiro LA, Antignac A, Jehanno M, Viala J, et al. Nod1 detects a unique muropeptide from gram-negative bacterial peptidoglycan. Science. 2003;300(5625):1584–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1084677 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303(5663):1532–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogawa M, Yoshimori T, Suzuki T, Sagara H, Mizushima N, Sasakawa C. Escape of intracellular Shigella from autophagy. Science. 2005;307(5710):727–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1106036 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hermansson AK, Paciello I, Bernardini ML. The orchestra and its maestro: Shigella's fine-tuning of the inflammasome platforms. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2016;397:91–115. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-41171-2_5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schroeder GN, Jann NJ, Hilbi H. Intracellular type III secretion by cytoplasmic Shigella flexneri promotes caspase-1-dependent macrophage cell death. Microbiology. 2007;153(9):2862–76. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/007427-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall C, Flores MV, Storm T, Crosier K, Crosier P. The zebrafish lysozyme C promoter drives myeloid-specific expression in transgenic fish. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:42 doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-42 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sirajuddin M, Farkasovsky M, Hauer F, Kuhlmann D, Macara IG, Weyand M, et al. Structural insight into filament formation by mammalian septins. Nature. 2007;449(7160):311–5. doi: 10.1038/nature06052 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dash SN, Lehtonen E, Wasik AA, Schepis A, Paavola J, Panula P, et al. Sept7b is essential for pronephric function and development of left-right asymmetry in zebrafish embryogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2014;127(7):1476–86. doi: 10.1242/jcs.138495 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li L, Jin H, Xu J, Shi Y, Wen Z. Irf8 regulates macrophage versus neutrophil fate during zebrafish primitive myelopoiesis. Blood. 2011;117(4):1359–69. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-290700 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnupf P, Sansonetti PJ. Quantitative RT-PCR profiling of the rabbit immune response: assessment of acute Shigella flexneri infection. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e36446 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036446 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang JY, Lee S, Chang S, Ko H, Ryu S, Kweon M. A mouse model of shigellosis by intraperitoneal infection. J Infec Dis. 2014;209(2):203–15. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit399 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen-Chi M, Phan QT, Gonzalez C, Dubremetz J-F, Levraud J-P, Lutfalla G. Transient infection of the zebrafish notochord with E. coli induces chronic inflammation. Dis Model Mech. 2014;7(7):871–82. doi: 10.1242/dmm.014498 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sollberger G, Strittmatter GE, Garstkiewicz M, Sand J, Beer H-D. Caspase-1: The inflammasome and beyond. Innate Immun. 2014;20(2):115–25. doi: 10.1177/1753425913484374 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miao EA, Rajan JV, Aderem A. Caspase-1-induced pyroptotic cell death. Immunological reviews. 2011;243(1):206–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01044.x . Epub 2011/09/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tobin DM, Roca FJ, Oh SF, McFarland R, Vickery TW, Ray JP, et al. Host genotype-specific therapies can optimize the inflammatory response to mycobacterial infections. Cell. 2012;148(3):434–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.023 . 3433720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aksentijevich I, Masters SL, Ferguson PJ, Dancey P, Frenkel J, van Royen-Kerkhoff A, et al. An autoinflammatory disease with deficiency of the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(23):2426–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807865 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hawkins PN, Lachmann HJ, McDermott MF. Interleukin-1–receptor antagonist in the Muckle–Wells syndrome. New Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2583–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200306193482523 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanther M, Rawls JF. Host–microbe interactions in the developing zebrafish. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22(1):10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.006 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Renshaw SA, Trede NS. A model 450 million years in the making: zebrafish and vertebrate immunity. Dis Model Mech. 2012;5(1):38–47. doi: 10.1242/dmm.007138 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vincent WJB, Freisinger CM, Lam Py, Huttenlocher A, Sauer JD. Macrophages mediate flagellin induced inflammasome activation and host defense in zebrafish. Cell Microbiol. 2015;18:591–604. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12536 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hall CJ, Boyle RH, Astin JW, Flores MV, Oehlers SH, Sanderson LE, et al. Immunoresponsive gene 1 augments bactericidal activity of macrophage-lineage cells by regulating beta-oxidation-dependent mitochondrial ROS production. Cell Metab. 2013;18(2):265–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.06.018 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phennicie RT, Sullivan MJ, Singer JT, Yoder JA, Kim CH. Specific resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in zebrafish is mediated by the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Infect Immun. 2010;78(11):4542–50. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00302-10 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCarthy RR, Mazon Moya MJ, Moscoso JA, Hao Y, Lam JS, Bordi C, et al. Cyclic-di-GMP regulates lipopolysaccharide modification and contributes to Pseudomonas aeruginosa immune evasion. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takaki K, Davis JM, Winglee K, Ramakrishnan L. Evaluation of the pathogenesis and treatment of Mycobacterium marinum infection in zebrafish. Nat Protoc. 2013;8(6):1114–24. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.068 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welch MD, Way M. Arp2/3-mediated actin-based motility: a tail of pathogen abuse. Cell Host Hicrobe. 2013;14(3):242–55. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.08.011 . Epub 2013/09/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colucci-Guyon E, Tinevez JY, Renshaw SA, Herbomel P. Strategies of professional phagocytes in vivo: unlike macrophages, neutrophils engulf only surface-associated microbes. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 18):3053–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.082792 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perdomo OJ, Cavaillon JM, Huerre M, Ohayon H, Gounon P, Sansonetti PJ. Acute inflammation causes epithelial invasion and mucosal destruction in experimental shigellosis. J Exp Med. 1994;180(4):1307–19. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Landsverk ML, Weiser DC, Hannibal MC, Kimelman D. Alternative splicing of sept9a and sept9b in zebrafish produces multiple mRNA transcripts expressed throughout development. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(5):0010712 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010712 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dash SN, Hakonen E, Ustinov J, Otonkoski T, Andersson O, Lehtonen S. Sept7b is required for the differentiation of pancreatic endocrine progenitors. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24992 doi: 10.1038/srep24992 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dash SN, Narumanchi S, Paavola J, Perttunen S, Wang H, Lakkisto P, et al. Sept7b is required for the subcellular organization of cardiomyocytes and cardiac function in zebrafish. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017:ajpheart 00394 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00394.2016 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhai G, Gu Q, He J, Lou Q, Chen X, Jin X, et al. Sept6 is required for ciliogenesis in Kupffer's vesicle, the pronephros, and the neural tube during early embryonic development. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(7):1310–21. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01409-13 . 3993556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carneiro LAM, Travassos LH, Soares F, Tattoli I, Magalhaes JG, Bozza MT, et al. Shigella induces mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death in nonmyleoid cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5(2):123–36. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.12.011 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zychlinsky A, Prevost MC, Sansonetti PJ. Shigella flexneri induces apoptosis in infected macrophages. Nature. 1992;358(6382):167–9. doi: 10.1038/358167a0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koterski JF, Nahvi M, Venkatesan MM, Haimovich B. Virulent Shigella flexneri causes damage to mitochondria and triggers necrosis in infected human monocyte-derived macrophages. Infect Immun. 2005;73(1):504–13. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.504-513.2005 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suzuki T, Franchi L, Toma C, Ashida H, Ogawa M, Yoshikawa Y, et al. Differential regulation of caspase-1 activation, pyroptosis, and autophagy via Ipaf and ASC in Shigella infected macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3(8):e111 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030111 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Willingham SB, Bergstralh DT, O'Connor W, Morrison AC, Taxman DJ, Duncan JA, et al. Microbial pathogen-induced necrotic cell death mediated by the inflammasome components CIAS1/cryopyrin/NLRP3 and ASC. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2(3):147–59. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.07.009 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:519–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Luca A, Smeekens SP, Casagrande A, Iannitti R, Conway KL, Gresnigt MS, et al. IL-1 receptor blockade restores autophagy and reduces inflammation in chronic granulomatous disease in mice and in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(9):3526–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322831111 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goldbach-Mansky R, Dailey NJ, Canna SW, Gelabert A, Jones J, Rubin BI, et al. Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease responsive to interleukin-1β inhibition. New Engl J Med. 2006;355(6):581–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055137 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vincent WJ, Freisinger CM, Lam PY, Huttenlocher A, Sauer JD. Macrophages mediate flagellin induced inflammasome activation and host defense in zebrafish. Cellular Microbiol. 2016;18(4):591–604. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12536 . 5027955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tyrkalska SD, Candel S, Angosto D, Gomez-Abellan V, Martin-Sanchez F, Garcia-Moreno D, et al. Neutrophils mediate Salmonella Typhimurium clearance through the GBP4 inflammasome-dependent production of prostaglandins. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12077 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12077 . 4932187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ellett F, Pase L, Hayman JW, Andrianopoulos A, Lieschke GJ. mpeg1 promoter transgenes direct macrophage-lineage expression in zebrafish. Blood. 2011;117(4):e49–e56. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-314120 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gray C, Loynes CA, Whyte MK, Crossman DC, Renshaw SA, Chico TJ. Simultaneous intravital imaging of macrophage and neutrophil behaviour during inflammation using a novel transgenic zebrafish. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105(5):811–9. doi: 10.1160/TH10-08-0525 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roca FJ, Ramakrishnan L. TNF dually mediates resistance and susceptibility to mycobacteria via mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Cell. 2013;153(3):521–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.022 . 3790588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Westerfield M. The zebrafish book A guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio). Eugene, Oregon: University of Oregon Press, Eugene; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 1995;203(3):253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mazon Moya MJ, Colluci-Guyon E, Mostowy S. Use of Shigella flexneri to study autophagy-cytoskeleton interactions. J Vis Exp. 2014;91: e51601 doi: 10.3791/51601 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stockhammer OW, Zakrzewska A, Hegedus Z, Spaink HP, Meijer AH. Transcriptome profiling and functional analyses of the zebrafish embryonic innate immune response to Salmonella infection. J Immunol. 2009;182(9):5641–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900082 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Progatzky F, Sangha NJ, Yoshida N, McBrien M, Cheung J, Shia A, et al. Dietary cholesterol directly induces acute inflammasome-dependent intestinal inflammation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5864 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6864 . 4284652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. Transverse section of larvae (3 dpf) infected in the HBV with S. flexneri M90T (low dose) for 6h. Arrow indicates the localisation of the bacteria inside the ventricle. Scale bar, 50 μm. E, eye; M, midbrain ventricle. B. Survival curves of larvae infected with low (≤ 3 x 103 CFU) or high (≥ 1 x 104 CFU) inoculum of T3SS- S. flexneri (ΔmxiD strain) using at least 15 larvae per experiment. Significance testing performed by Log Rank test. C. Enumeration of bacteria at 0, 24, or 48 hpi from larvae infected with low (open circles) or high (closed circles) dose of S. flexneri M90T using up to 3 larvae per treatment. Circles represent individual larvae. Mean ± SEM also shown (horizontal bars). Significance testing performed by Student’s t test. **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. Note bacterial load does not significantly decrease in highly infected fish because of the high bacteria:leukocyte ratio and thus more time is required to clear the bacterial burden. D. Frames extracted from in vivo time-lapse confocal imaging of mpeg1:G/U:mCherry x mpx:GFP larvae (3 dpf) injected in the HBV with low dose of Crimson-S. flexneri. First frame 20 mpi, followed by frames at 1, 3, and 12 hpi. Maximum intensity Z-projection images (2 μm serial optical sections) are shown. Scale bars, 50 μm. See also S1 Video.

(TIF)