Abstract

The oxygen-sensitive hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway plays a central role in the control of erythropoiesis and iron metabolism. The discovery of prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) proteins as key regulators of HIF activity has led to the development of inhibitory compounds that are now in phase 3 clinical development for the treatment of renal anemia, a condition that is commonly found in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. This review provides a concise overview of clinical effects associated with pharmacologic PHD inhibition and was written in memory of Professor Lorenz Poellinger.

Keywords: Hypoxia, Hypoxia-inducible factor, Anemia, Prolyl hydroxylase domain, Chronic kidney disease, Clinical trials, Oxygen

Introduction to hypoxia-inducible factor and prolyl hydroxylase domain oxygen sensors

The recent identification of oxygen- and iron-dependent prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) enzymes as regulators of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-dependent erythropoiesis has led to the development of novel therapeutic agents that are currently in clinical development for the treatment of anemia associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

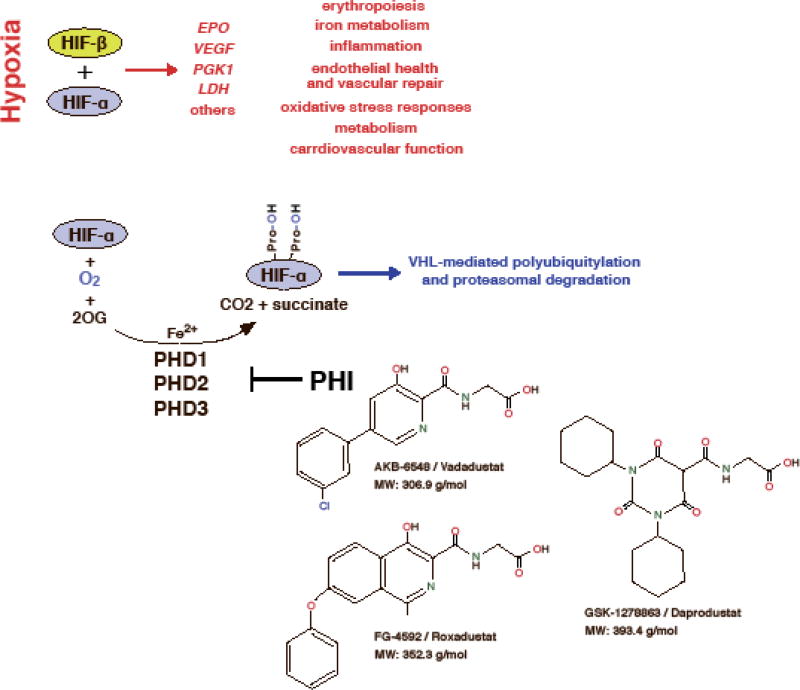

HIFs are basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors and members of the PAS (PER/aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT)/single minded (SIM)) family of transcription factors. They consist of an oxygen-sensitive α-subunit and a constitutively expressed β-subunit, which is often referred to as the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT). Three HIF-α-subunits have been identified, HIF-1α, HIF-2α (also known as EPAS1) and HIF-3α [1–3]. HIF-1 and HIF-2 are the most extensively studied HIF transcription factors and facilitate oxygen delivery and adaptation to hypoxia by regulating a wide spectrum of cellular and tissue hypoxia responses. These include the stimulation of red blood cell (rbc) production and angiogenesis, the induction of glycolysis, reductions in fat and mitochondrial metabolism, as well as alterations in cardiovascular function (Figure 1) [4, 5]. HIF-α-subunits, although continuously synthesized, are rapidly degraded in the presence of molecular oxygen. When cells experience hypoxia HIF-α is no longer degraded and translocates to the nucleus where it forms a heterodimer with HIF-β and activates gene transcription (Figure 1) [6].

Figure 1. Overview of the HIF oxygen-sensing pathway.

Although the oxygen-sensitive HIF-α subunit is constitutively synthesized, it is rapidly degraded under normoxic conditions. Under hypoxia, however, cellular HIF-α levels build up and HIF-α translocates to the nucleus, where it forms a heterodimer with HIF-β. Proteasomal degradation of HIF-α is mediated by the pVHL-E3-ubiquitin ligase complex and requires HIF-α prolyl-4-hydroxylation by oxygen- and iron-dependent PHD enzymes (PHD1-3). The decarboxylation of 2-oxoglutarate (2OG) produces hydroxylated HIF-α, succinate and CO2. A reduction in PHD catalytic activity (e.g. due to hypoxia or pharmacologic inhibition) results in increased transcription of HIF-regulated genes such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), erythropoietin (EPO), phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and other genes involved in the regulation of hypoxia responses. Shown are the chemical structures of three PHD inhibitors (PHI), which are now in phase 3 clinical development for renal anemia. A common characteristic of daprodustat, roxadustat and vadadustat is a carbonylglycine side chain that is structurally analogous to 2OG.

Hydroxylation of specific proline residues is required for normoxic HIF-α degradation and is carried out by PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3, which function as the oxygen sensors of the HIF pathway [7]. HIF-PHDs belong to a large family of 2-oxoglutarate (OG)-dependent dioxygenases. These enzymes utilize molecular oxygen for hydroxylation and thus couple oxygen, intermediary and amino acid metabolism to multiple cellular processes, which include HIF responses, collagen synthesis, fatty acid metabolism and the regulation of the epigenome [8]. Any reduction in HIF-proline hydroxylation impairs HIF-α degradation and leads to the activation of HIF-mediated cellular hypoxia responses. Structural analogs of 2OG that reversibly inhibit HIF-proline hydroxylation {HIF-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors (HIF-PHIs)} have been shown to effectively stimulate HIF responses in the presence of normal oxygen levels and are now in clinical development for renal anemia therapy and other indications [9].

HIF-prolyl hydroxylases in the regulation of erythropoiesis

The hypoxic induction of erythropoiesis represents a classic mammalian response to hypoxia and is initiated by the rapid production of erythropoietin (EPO), the glycoprotein hormone that is essential for normal red blood cell (rbc) production [9]. While the kidney is the main site of EPO synthesis in adults, the liver can be stimulated to significantly contribute to plasma EPO levels under moderate to severe systemic hypoxia or following the administration of HIF-PHIs [9]. The induction of EPO synthesis in the kidney and liver is HIF-2 dependent and pharmacologic or genetic HIF-2α stabilization results in robust EPO synthesis in both organs leading to increased rbc production [10–12]. PHD2 inactivation in renal interstitial cells with EPO-producing potential is sufficient for robust HIF-2α stabilization and EPO induction in the kidney [11–14]. In contrast, the inactivation of all three HIF-PHDs is required to achieve a comparable degree of EPO synthesis in the liver [13, 15]. In humans, certain PHD2 mutations can be inherited and are associated with the development of polycythemia [16].

Perivascular interstitial fibroblasts and pericytes are the cellular sites of EPO production in the kidney. Under baseline conditions a small number of renal EPO-producing cells (EPC) localizes to the deep cortex and outer medulla, whereas under hypoxia EPC can be found throughout the entire renal cortex and outer medulla. Studies from our and other laboratories indicate that the majority of cortical perivascular fibroblasts and pericytes have the capacity to produce EPO [17–20]. Cortical perivascular fibroblasts and pericytes do not only have the ability to produce EPO but are also the main source of collagen-producing myofibroblasts and thus provide a cellular link between renal fibrosis and anemia development [21–23]. Pathologic conditions, such as CKD, impede the kidney’s ability to synthesize EPO and lead to inadequate EPO production resulting in anemia. In animal models the loss of EPO-producing ability is associated with increased NF-κB signaling in interstitial cells and can potentially be reversed with corticosteroid treatment [19, 24]. Furthermore, it has been proposed that stabilization of HIF-2α following genetic PHD inactivation protects renal EPO-producing capacity in a renal fibrosis model induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction [25].

The number of EPC within the kidney and thus renal EPO output is likely to be modulated by intercellular crosstalk between different renal cells types. While these intercellular relationships are ill defined, studies from our group have shown that HIF-induced reprogramming of epithelial metabolism suppresses EPO production partly through alterations in renal tissue pO2. These findings are consistent with the observation that administration of certain diuretics, possibly through their effects on tubular work load and oxygen consumption, have the ability to modulate EPO production in the kidney [26].

The HIF axis not only regulates the hypoxic induction of EPO but also coordinates renal and liver EPO production with the expression of multiple genes involved in iron metabolism, as iron is needed for efficient erythropoiesis. As demonstrated in animal models of iron-deficiency and hemochromatosis, HIF-2 increases the transcription of divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) and duodenal cytochrome b (DCYTB) promoting iron uptake in the gut [27–29]. HIF furthermore increases the transcription of transferrin, which transports iron in blood, transferrin receptor TFR1 [30–32], ceruloplasmin, which oxidizes Fe2+ to Fe3+ and is also important for iron transport [33], hemeoxygenase-1, which is involved in the recycling of iron from phagocytosed erythrocytes [34], and ferroportin (FPN) [35], the only known cellular iron exporter, which is present in intestinal cells involved in iron uptake, hepatocytes, macrophages and other cell types. FPN surface expression is regulated by hepcidin, a small 25-amino-acid peptide produced in the liver. Its production is increased by iron and inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 6. Because hepcidin promotes FPN internalization and degradation, it suppresses FPN cell surface expression. High plasma hepcidin levels are therefore associated with reduced intestinal iron uptake and impaired release of iron from internal stores [36]. Hypoxia and systemic HIF activation suppress hepcidin production in the liver and thus enhance iron uptake and mobilization [37, 38]. However the effects of HIF on hepatic hepcidin production are indirect, i.e. HIF does not act as a direct transcriptional repressor of hepcidin, as the hypoxia-induced suppression of hepatic hepcidin production results from the increased release of erythroferrone a hormone produced by EPO-stimulated erythroblasts [39–41].

In addition to regulating iron metabolism, hypoxia and/or the HIF pathway stimulate erythropoiesis through direct effects on the bone marrow via stimulation of EPOR expression, hemoglobin synthesis [42–46] and modulation of stem cell maintenance, lineage differentiation and maturation [47, 48].

Rational for using HIF-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors in patients with renal anemia

Most patients with GFRs of less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 develop anemia [49], which is due to the relative underproduction of renal EPO, the presence of relative and/or absolute iron deficiency, inflammation and uremic toxins [9]. Although the liver significantly contributes to plasma EPO levels in patients with advanced CKD [50], hepatic EPO production is not sufficient to maintain hemoglobin at normal levels. HIF has become an attractive target for anemia therapy as it not only stimulates renal and hepatic EPO production, but also promotes iron uptake and utilization, and facilitates erythroid progenitor maturation and proliferation [9]. Furthermore activation of the HIF pathway with orally administered HIF-PHIs suppresses hepcidin production in the liver, thus enhancing iron uptake and mobilization [37, 38]. This however is not directly mediated by HIF [9, 40].

The administration of recombinant EPO together with oral or injectable iron preparations represents current standard of care for patients with renal anemia [51, 52]. Recombinant EPO therapy is effective in maintaining hemoglobin levels and its use has reduced the need for red blood cell transfusions. Some patients, however, have suboptimal responses or require very high doses of recombinant EPO to achieve target hemoglobin levels. These EPO-resistant patients most commonly have significant inflammation and/or iron deficiency, each of which suppresses EPO production and has negative effects on erythropoietic progenitor cells [9]. Although clinically effective, recombinant EPO therapy is associated with increased risk for cardiovascular events such as stroke and myocardial infarction [53–55]. It is likely that recombinant EPO-associated cardiovascular risk is directly related to a) intermittent supra-physiologic plasma EPO levels due to high doses of recombinant EPO, b) hemoglobin oscillations and c) excursions of hemoglobin levels beyond target range [56–60].

The discovery of HIF-prolyl hydroxylases as key regulators of erythropoiesis has catalyzed the development of novel therapeutic agents that reversibly inhibit HIF-prolyl hydroxylation, here referred to as HIF-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors (HIF-PHIs). HIF-PHIs induce a transient increase in the expression of HIF-regulated genes, including renal and hepatic EPO [61]. Plasma EPO levels in patients treated with HIF-PHIs are significantly lower than in patients treated with injectable recombinant EPO [62, 63]. Pending data from phase 3 clinical trials, HIF-PHI therapy therefore holds promise to reduce cardiovascular risk associated with recombinant EPO therapy. Furthermore HIF-PHIs have beneficial effects on iron homeostasis, as they lower hepcidin and ferritin and increase total iron binding capacity in patients with CKD [62–67].

In summary, owing to their dual action on EPO production and iron homeostasis pharmacologic targeting of the HIF oxygen-sensing pathway has become a very attractive therapeutic approach for the treatment of anemia. Pending comprehensive safety evaluations HIF-PHIs have the potential to replace recombinant EPO in the long term care of patients with CKD.

Clinical experience with HIF-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors and safety

Several HIF-PHIs have been developed and are currently undergoing clinical investigation in non-dialysis-dependent CKD patients, EPO-naïve dialysis-dependent patients and dialysis patients who were previously treated with recombinant EPO (Table 1). Peer-reviewed clinical data from randomized controlled trials are available for three orally administered compounds, daprodustat (GSK-1278863), roxadustat (FG-4592) and vadadustat (AKB-6548) (Figure 1). These compounds effectively stimulated erythropoiesis in a titratable manner, had beneficial effects on iron metabolism and have now progressed to phase 3 clinical development. In addition to stimulating erythropoiesis, HIF-PHIs have been shown to produce non-erythropoietic effects, such as lowering serum cholesterol levels in CKD patients and reducing arterial blood pressure in an animal model of CKD [62, 63, 65, 68, 69].

Table 1.

Overview of HIF-PHIs in clinical development.

| Compound | Ref | Status of clinical development |

HIF-α stabilization |

HIF-PHD targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKB-6548 (Vadadustat) Akebia Therapeutics | [67, 93, 94] | Phase 3 | HIF-2α > HIF-1α | PHD3 > PHD2 |

| GSK-1278863 (Daprodustat) GlaxoSmithKline | [62, 87, 89, 95] | Phase 3 | HIF-1α and HIF-2α | PHD2 and PHD3 |

| FG-4592 (Roxadustat) Fibrogen/Astellas Pharma/AstraZeneca | [63–66] | Phase 3 | HIF-1α and HIF-2α | PHD1, 2 and 3 |

| BAY 85-3934 (Molidustat) Bayer Pharma | [69, 96, 97] | Phase 2 | HIF-1α and HIF-2α | PHD2 > PHD1/PHD3 |

| JTZ-951 Japan Tabacco, Inc. / Akros Pharma, Inc. | [98] | Phase 2 | not published | not published |

| Zyan1 Cadila Healthcare | [99, 100] | Phase 1 | not published | not published |

| TP0463518 Taisho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. | [101] | Phase 1 | not published, possibly liver-specific | not published, possibly liver-specific |

| JNJ-42905343 Janssen | [102] | pre-clinical | HIF-1α and HIF-2α | PHD1, 2 and 3 |

| DS-1093 Daiichi Sankyo, Inc. | - | under evaluation for other indications, discontinued for renal anemia | not published | not published |

Information in this table is based on a review of the literature, meeting abstracts and other publicly available resources such as patent applications.

Although HIF-PHIs have been well tolerated in short-term phase 2 clinical trials, there are several safety concerns relating to the potential non-erythropoietic effects resulting from repeated normoxic HIF activation. The quality and extent of these non-erythropoietic effects are likely to be determined by the degree and duration of HIF activation, the cell types involved, and the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of individual HIF-PHIs. In addition to HIF-mediated adverse effects, HIF-PHIs have the potential to interfere with cell signaling pathways that involve proline-hydroxylation of non-HIF signaling molecules or other non-HIF dioxygenases. Preliminary meeting reports however suggest that daprodustat, roxadustat, vadadustat and molidustat are relatively specific for HIF-PHDs with IC50s of > 100µm for factor inhibiting HIF (FIH) and dioxygenases involved in epigenetic gene regulation. FIH is an asparaginyl hydroxylase that modulates co-factor recruitment to the HIF transcriptional complex [70–72].

HIF-1 and HIF-2 transcription factors regulate of a broad spectrum of cellular functions and biological processes. These include angiogenesis, glucose, fatty acid, cholesterol and mitochondrial metabolism, signaling pathways that control cell growth and cell death, cardiovascular functions, inflammation, cell motility and matrix production [4]. Phenotypic analysis of genetically modified animal models (e.g. VHL or PHD conditional knockout mice) has been frequently used to predict potential adverse HIF-dependent effects that may occur in patients treated with HIF-PHIs. Although genetic studies in animals have provided important insights into cell- and context-specific HIF functions in pathogenesis, the effects of short-term HIF activation in patients with CKD may be difficult to predict from in vivo models with permanent and irreversible activation of the HIF pathway. However, more clinically relevant information regarding the type and likelihood of potential adverse clinical effects due to HIF-PHI therapy may be obtained from the study of patients with genetic mutations in the PHD/HIF pathway, for example patients with Chuvash polycythemia, who are homozygous for a specific VHL mutation (R200W) [73–75].

Patients with VHL mutation R200W are predisposed to the development of polycythemia and vascular complications such as pulmonary hypertension, cerebral vascular events and peripheral thromboembolism [73–76]. Furthermore, Chuvash patients have increased pulmonary and vascular sensitivity to hypoxia and altered skeletal muscle metabolism [77, 78]. Metabolic alterations were also observed in the heart from mice homozygous for the Chuvash mutation [79]. Increased systolic pulmonary artery pressures were also found in patients with mutations in HIF2A and PHD2 [75, 80]. Patients with HIF2A gain-of-function mutations are furthermore characterized by a statistically significant increase in baseline heart rate and cardiac output, which is in contrast to patients with Chuvash polycythemia [75]. Interestingly, the pulmonary vascular phenotype of a polycythemic patient with PHD2 mutation was relatively mild compared to Chuvash patients. This was attributed to potential differences in the ratio of HIF-1α versus HIF-2α stabilization, the presence of severe iron deficiency in Chuvash patients and to potential HIF-independent effects associated with VHL mutations [80].

HIF-2 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension independent of erythrocytosis [81–84], which raises the possibility that HIF-PHI therapy may adversely affect pulmonary artery pressure regulation in patients with CKD who are characterized by an increased risk for the development of pulmonary hypertension [85]. With regard to arterial blood pressure regulation, HIF-PHI therapy seems to be associated with a trend towards decreasing rather than increasing blood pressure [68, 69].

HIF is a well-established and potent stimulator of angiogenesis and induces the transcription of several pro-angiogenic molecules such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Therefore HIF-PHI therapy has the potential to increase the production of VEGF, which could produce pro-oncogenic effects or exacerbate pathologic conditions that are characterized by excessive vascular proliferation, such as diabetic retinopathy. Notwithstanding these concerns, statistically significant increases in plasma VEGF levels were not found in phase 2 clinical trials [62, 67], which most likely due to dosing effects. Daprodustat for example increased plasma VEGF concentrations at doses of ≥ 50 mg, which are above those used in the clinical studies published by Holdstock and colleagues (1 to 5 mg) [86, 87].

HIF has been shown to regulate glucose, fatty acid, cholesterol metabolism and mitochondrial function [4, 88]. Some of these metabolic effects are also seen in patients treated with HIF-PHIs. A decrease in serum cholesterol levels was reported for daprodustat and roxadustat [62, 63, 65], whereas a trend for increased glucose was noted in patients treated with relatively high doses of daprodustat (50 mg and 100 mg) [89]. To what degree intermittent HIF activation will affect glucose homeostasis and fatty acid metabolism in diabetic patients remains to be determined in phase 3 clinical trials.

Safety concerns also exist with regard to HIF’s role in the regulation of tumor cell growth and metastasis, as activation of HIF signaling in malignant cells has been associated with tumor initiation and progression [90].

HIF has been shown to be involved in the regulation of matrix turnover and fibrogenesis and it is not clear whether HIF activation in the kidney protects from fibrosis or promotes the progression of CKD [91, 92]. Long-term clinical studies are needed to address this issue. Another potential adverse effect that may be observed in CKD patients on HIF-PHI therapy is hepatic toxicity. FG2216, the sister compound of roxadustat was taken out of clinical trials due to one case of fatal hepatic necrosis, although the death of the concerning patient was not attributed to the study medication [9]. To date HIF-PHIs have been well tolerated and significant liver toxicity has not been reported.

In summary, HIF-PHIs are effective in treating anemia associated with CKD, and have been well tolerated in phase 2 clinical trials. However, long-term clinical safety studies in CKD patients and comprehensive physiologic evaluations in healthy volunteers are needed for a better understanding of the cardiovascular and metabolic consequences of pharmacologic PHD inhibition before HIF-PHIs can be safely administered to patients over longer periods of time.

Acknowledgments

This review was written in memory of the late Professor Lorenz Poellinger, a great colleague, teacher and friend. VHH holds the Krick-Brooks chair in Nephrology at Vanderbilt University and is supported by NIH grants R01-DK101791 and R01-DK081646, and a Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Award 1I01BX002348. The author apologizes to those colleagues whose work could not be cited due to space limitations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict-of-interest statement

VHH serves on the scientific advisory board of Akebia Therapeutics, Inc., a company that develops PHD inhibitors for the treatment of anemia

References

- 1.Semenza GL. Regulation of mammalian O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:551–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kewley RJ, Whitelaw ML, Chapman-Smith A. The mammalian basic helix-loop-helix/PAS family of transcriptional regulators. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:189–204. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wenger RH, Stiehl DP, Camenisch G. Integration of oxygen signaling at the consensus HRE. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:re12. doi: 10.1126/stke.3062005re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semenza GL. Oxygen sensing, hypoxia-inducible factors, and disease pathophysiology. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:47–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semenza GL. Regulation of metabolism by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:347–53. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2011.76.010678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Semenza GL. HIF-1 and mechanisms of hypoxia sensing. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:167–71. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaelin WG, Jr, Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell. 2008;30:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loenarz C, Schofield CJ. Expanding chemical biology of 2-oxoglutarate oxygenases. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:152–6. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0308-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koury MJ, Haase VH. Anaemia in kidney disease: harnessing hypoxia responses for therapy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11:394–410. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapitsinou PP, Liu Q, Unger TL, Rha J, Davidoff O, Keith B, et al. Hepatic HIF-2 regulates erythropoietic responses to hypoxia in renal anemia. Blood. 2010;116:3039–48. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeda K, Aguila HL, Parikh NS, Li X, Lamothe K, Duan LJ, et al. Regulation of adult erythropoiesis by prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins. Blood. 2008;111:3229–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-114561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minamishima YA, Moslehi J, Bardeesy N, Cullen D, Bronson RT, Kaelin WG., Jr Somatic inactivation of the PHD2 prolyl hydroxylase causes polycythemia and congestive heart failure. Blood. 2008;111:3236–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minamishima YA, Kaelin WG., Jr Reactivation of hepatic EPO synthesis in mice after PHD loss. Science. 2010;329:407. doi: 10.1126/science.1192811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi H, Liu Q, Binns TC, Urrutia AA, Davidoff O, Kapitsinou PP, et al. Distinct subpopulations of FOXD1 stroma-derived cells regulate renal erythropoietin. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:1926–38. doi: 10.1172/JCI83551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tojo Y, Sekine H, Hirano I, Pan X, Souma T, Tsujita T, et al. Hypoxia Signaling Cascade for Erythropoietin Production in Hepatocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35:2658–72. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00161-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee FS, Percy MJ. The HIF pathway and erythrocytosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:165–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koury ST, Bondurant MC, Koury MJ. Localization of erythropoietin synthesizing cells in murine kidneys by in situ hybridization. Blood. 1988;71:524–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obara N, Suzuki N, Kim K, Nagasawa T, Imagawa S, Yamamoto M. Repression via the GATA box is essential for tissue-specific erythropoietin gene expression. Blood. 2008;111:5223–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-115857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Souma T, Yamazaki S, Moriguchi T, Suzuki N, Hirano I, Pan X, et al. Plasticity of renal erythropoietin-producing cells governs fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1599–616. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013010030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamazaki S, Souma T, Hirano I, Pan X, Minegishi N, Suzuki N, et al. A mouse model of adult-onset anaemia due to erythropoietin deficiency. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1950. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin SL, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA, Duffield JS. Pericytes and perivascular fibroblasts are the primary source of collagen-producing cells in obstructive fibrosis of the kidney. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1617–27. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humphreys BD, Lin SL, Kobayashi A, Hudson TE, Nowlin BT, Bonventre JV, et al. Fate tracing reveals the pericyte and not epithelial origin of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2009;176:85–97. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falke LL, Gholizadeh S, Goldschmeding R, Kok RJ, Nguyen TQ. Diverse origins of the myofibroblast-implications for kidney fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asada N, Takase M, Nakamura J, Oguchi A, Asada M, Suzuki N, et al. Dysfunction of fibroblasts of extrarenal origin underlies renal fibrosis and renal anemia in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3981–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI57301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Souma T, Nezu M, Nakano D, Yamazaki S, Hirano I, Sekine H, et al. Erythropoietin Synthesis in Renal Myofibroblasts Is Restored by Activation of Hypoxia Signaling. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:428–38. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014121184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckardt KU, Kurtz A, Bauer C. Regulation of erythropoietin production is related to proximal tubular function. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:F942–7. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.256.5.F942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah YM, Matsubara T, Ito S, Yim SH, Gonzalez FJ. Intestinal hypoxia-inducible transcription factors are essential for iron absorption following iron deficiency. Cell Metab. 2009;9:152–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mastrogiannaki M, Matak P, Keith B, Simon MC, Vaulont S, Peyssonnaux C. HIF-2alpha, but not HIF-1alpha, promotes iron absorption in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1159–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI38499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mastrogiannaki M, Matak P, Delga S, Deschemin JC, Vaulont S, Peyssonnaux C. Deletion of HIF-2alpha in the enterocytes decreases the severity of tissue iron loading in hepcidin knockout mice. Blood. 2011;119:587–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-380337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rolfs A, Kvietikova I, Gassmann M, Wenger RH. Oxygen-regulated transferrin expression is mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20055–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.20055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lok CN, Ponka P. Identification of a hypoxia response element in the transferrin receptor gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24147–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tacchini L, Bianchi L, Bernelli-Zazzera A, Cairo G. Transferrin receptor induction by hypoxia. HIF-1-mediated transcriptional activation and cell-specific post-transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24142–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mukhopadhyay CK, Mazumder B, Fox PL. Role of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in transcriptional activation of ceruloplasmin by iron deficiency. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21048–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000636200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee PJ, Jiang BH, Chin BY, Iyer NV, Alam J, Semenza GL, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates transcriptional activation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene in response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5375–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor M, Qu A, Anderson ER, Matsubara T, Martin A, Gonzalez FJ, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha mediates the adaptive increase of intestinal ferroportin during iron deficiency in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:2044–55. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ganz T. Molecular control of iron transport. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:394–400. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006070802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nicolas G, Chauvet C, Viatte L, Danan JL, Bigard X, Devaux I, et al. The gene encoding the iron regulatory peptide hepcidin is regulated by anemia, hypoxia, and inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1037–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI15686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gordeuk VR, Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, Niu X, Nouraie M, Okhotin DJ, et al. Chuvash polycythemia VHLR200W mutation is associated with down-regulation of hepcidin expression. Blood. 2011;118:5278–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-345512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mastrogiannaki M, Matak P, Mathieu JR, Delga S, Mayeux P, Vaulont S, et al. Hepatic hypoxia-inducible factor-2 down-regulates hepcidin expression in mice through an erythropoietin-mediated increase in erythropoiesis. Haematologica. 2012;97:827–34. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.056119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Q, Davidoff O, Niss K, Haase VH. Hypoxia-inducible factor regulates hepcidin via erythropoietin-induced erythropoiesis. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4635–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI63924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kautz L, Jung G, Valore EV, Rivella S, Nemeth E, Ganz T. Identification of erythroferrone as an erythroid regulator of iron metabolism. Nat Genet. 2014;46:678–84. doi: 10.1038/ng.2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chin K, Yu X, Beleslin-Cokic B, Liu C, Shen K, Mohrenweiser HW, et al. Production and processing of erythropoietin receptor transcripts in brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;81:29–42. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hofer T, Wenger RH, Kramer MF, Ferreira GC, Gassmann M. Hypoxic up-regulation of erythroid 5-aminolevulinate synthase. Blood. 2003;101:348–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manalo DJ, Rowan A, Lavoie T, Natarajan L, Kelly BD, Ye SQ, et al. Transcriptional regulation of vascular endothelial cell responses to hypoxia by HIF-1. Blood. 2005;105:659–69. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu YL, Ang SO, Weigent DA, Prchal JT, Bloomer JR. Regulation of ferrochelatase gene expression by hypoxia. Life Sci. 2004;75:2035–43. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoon D, Pastore YD, Divoky V, Liu E, Mlodnicka AE, Rainey K, et al. HIF-1alpha-deficiency results in dysregulated EPO signaling and iron homeostasis in mouse development. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25703–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adelman DM, Maltepe E, Simon MC. Multilineage embryonic hematopoiesis requires hypoxic ARNT activity. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2478–83. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamashita T, Ohneda O, Sakiyama A, Iwata F, Ohneda K, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. The microenvironment for erythropoiesis is regulated by HIF-2alpha through VCAM-1 in endothelial cells. Blood. 2008;112:1482–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-122648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nangaku M, Eckardt KU. Pathogenesis of renal anemia. Semin Nephrol. 2006;26:261–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lonnberg M, Garle M, Lonnberg L, Birgegard G. Patients with anaemia can shift from kidney to liver production of erythropoietin as shown by glycoform analysis. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2013;81–82:187–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jelkmann W. The ESA scenario gets complex: from biosimilar epoetins to activin traps. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:553–9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jelkmann W. Erythropoietin after a century of research: younger than ever. Eur J Haematol. 2007;78:183–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Besarab A, Bolton WK, Browne JK, Egrie JC, Nissenson AR, Okamoto DM, et al. The effects of normal as compared with low hematocrit values in patients with cardiac disease who are receiving hemodialysis and epoetin. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:584–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808273390903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, Barnhart H, Sapp S, Wolfson M, et al. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2085–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen CY, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Eckardt KU, et al. A trial of darbepoetin alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361:2019–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Szczech LA, Barnhart HX, Inrig JK, Reddan DN, Sapp S, Califf RM, et al. Secondary analysis of the CHOIR trial epoetin-alpha dose and achieved hemoglobin outcomes. Kidney Int. 2008;74:791–8. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Besarab A, Frinak S, Yee J. What is so bad about a hemoglobin level of 12 to 13 g/dL for chronic kidney disease patients anyway? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2009;16:131–42. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vaziri ND, Zhou XJ. Potential mechanisms of adverse outcomes in trials of anemia correction with erythropoietin in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1082–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Solomon SD, Uno H, Lewis EF, Eckardt KU, Lin J, Burdmann EA, et al. Erythropoietic response and outcomes in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1146–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCullough PA, Barnhart HX, Inrig JK, Reddan D, Sapp S, Patel UD, et al. Cardiovascular toxicity of epoetin-alfa in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2013;37:549–58. doi: 10.1159/000351175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bernhardt WM, Wiesener MS, Scigalla P, Chou J, Schmieder RE, Gunzler V, et al. Inhibition of prolyl hydroxylases increases erythropoietin production in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:2151–6. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010010116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holdstock L, Meadowcroft AM, Maier R, Johnson BM, Jones D, Rastogi A, et al. Four-Week Studies of Oral Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitor GSK1278863 for Treatment of Anemia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:1234–44. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014111139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Provenzano R, Besarab A, Wright S, Dua S, Zeig S, Nguyen P, et al. Roxadustat (FG-4592) Versus Epoetin Alfa for Anemia in Patients Receiving Maintenance Hemodialysis: A Phase 2, Randomized, 6- to 19-Week, Open-Label, Active-Comparator, Dose-Ranging, Safety and Exploratory Efficacy Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67:912–24. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Besarab A, Provenzano R, Hertel J, Zabaneh R, Klaus SJ, Lee T, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled dose-ranging and pharmacodynamics study of roxadustat (FG-4592) to treat anemia in nondialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (NDD-CKD) patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:1665–73. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Provenzano R, Besarab A, Sun CH, Diamond SA, Durham JH, Cangiano JL, et al. Oral Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitor Roxadustat (FG-4592) for the Treatment of Anemia in Patients with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:982–91. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06890615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Besarab A, Chernyavskaya E, Motylev I, Shutov E, Kumbar LM, Gurevich K, et al. Roxadustat (FG-4592): Correction of Anemia in Incident Dialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:1225–33. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015030241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pergola PE, Spinowitz BS, Hartman CS, Maroni BJ, Haase VH. Vadadustat, a novel oral HIF stabilizer, provides effective anemia treatment in nondialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2016;90:1115–22. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hartman C, Smith MT, Flinn C, Shalwitz I, Peters KG, Shalwitz R, et al. AKB-6548, A New Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitor Increases Hemoglobin While Decreasing Ferritin in a 28-day, Phase 2a Dose Escalation Study in Stage 3 and 4 Chronic Kidney Disease Patients With Anemia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:435A. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Flamme I, Oehme F, Ellinghaus P, Jeske M, Keldenich J, Thuss U. Mimicking Hypoxia to Treat Anemia: HIF-Stabilizer BAY 85-3934 (Molidustat) Stimulates Erythropoietin Production without Hypertensive Effects. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mahon PC, Hirota K, Semenza GL. FIH-1: a novel protein that interacts with HIF-1alpha and VHL to mediate repression of HIF-1 transcriptional activity. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2675–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.924501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lando D, Peet DJ, Gorman JJ, Whelan DA, Whitelaw ML, Bruick RK. FIH-1 is an asparaginyl hydroxylase enzyme that regulates the transcriptional activity of hypoxia-inducible factor. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1466–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.991402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McNeill LA, Hewitson KS, Claridge TD, Seibel JF, Horsfall LE, Schofield CJ. Hypoxia-inducible factor asparaginyl hydroxylase (FIH-1) catalyses hydroxylation at the beta-carbon of asparagine-803. Biochem J. 2002;367:571–5. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gordeuk VR, Sergueeva AI, Miasnikova GY, Okhotin D, Voloshin Y, Choyke PL, et al. Congenital disorder of oxygen sensing: association of the homozygous Chuvash polycythemia VHL mutation with thrombosis and vascular abnormalities but not tumors. Blood. 2004;103:3924–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gordeuk VR, Prchal JT. Vascular complications in Chuvash polycythemia. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2006;32:289–94. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Formenti F, Beer PA, Croft QP, Dorrington KL, Gale DP, Lappin TR, et al. Cardiopulmonary function in two human disorders of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway: von Hippel-Lindau disease and HIF-2{alpha} gain-of-function mutation. FASEB Journal. 2011;25:2001–11. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-177378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sable CA, Aliyu ZY, Dham N, Nouraie M, Sachdev V, Sidenko S, et al. Pulmonary artery pressure and iron deficiency in patients with upregulation of hypoxia sensing due to homozygous VHL(R200W) mutation (Chuvash polycythemia) Haematologica. 2012;97:193–200. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.051839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith TG, Brooks JT, Balanos GM, Lappin TR, Layton DM, Leedham DL, et al. Mutation of von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor and human cardiopulmonary physiology. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Formenti F, Constantin-Teodosiu D, Emmanuel Y, Cheeseman J, Dorrington KL, Edwards LM, et al. Regulation of human metabolism by hypoxia-inducible factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12722–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002339107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Slingo M, Cole M, Carr C, Curtis MK, Dodd M, Giles L, et al. The von Hippel-Lindau Chuvash mutation in mice alters cardiac substrate and high-energy phosphate metabolism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;311:H759–67. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00912.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Talbot NP, Smith TG, Balanos GM, Dorrington KL, Maxwell PH, Robbins PA. Cardiopulmonary phenotype associated with human PHD2 mutation. Physiol Rep. 2017;5 doi: 10.14814/phy2.13224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kapitsinou PP, Rajendran G, Astleford L, Michael M, Schonfeld MP, Fields T, et al. The Endothelial Prolyl-4-Hydroxylase Domain 2/Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 2 Axis Regulates Pulmonary Artery Pressure in Mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2016;36:1584–94. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01055-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cowburn AS, Crosby A, Macias D, Branco C, Colaco RD, Southwood M, et al. HIF2alpha-arginase axis is essential for the development of pulmonary hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:8801–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602978113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bryant AJ, Carrick RP, McConaha ME, Jones BR, Shay SD, Moore CS, et al. Endothelial HIF signaling regulates pulmonary fibrosis-associated pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2016;310:L249–62. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00258.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dai Z, Li M, Wharton J, Zhu MM, Zhao YY. Prolyl-4 Hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) Deficiency in Endothelial Cells and Hematopoietic Cells Induces Obliterative Vascular Remodeling and Severe Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Mice and Humans Through Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-2alpha. Circulation. 2016;133:2447–58. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bolignano D, Rastelli S, Agarwal R, Fliser D, Massy Z, Ortiz A, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61:612–22. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brigandi RA, Russ SF, Al-Banna M, Zhang J, Erickson-Miller CL, Peng B. Prolylhydroxylase Inhibitor Modulation of Erythropoietin in a Randomized Placebo Controlled Trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:390A. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hara K, Takahashi N, Wakamatsu A, Caltabiano S. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety of single, oral doses of GSK1278863, a novel HIF-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor, in healthy Japanese and Caucasian subjects. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2015;30:410–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dmpk.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Haase VH. Renal cancer: oxygen meets metabolism. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318:1057–67. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brigandi RA, Johnson B, Oei C, Westerman M, Olbina G, de Zoysa J, et al. A Novel Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitor (GSK1278863) for Anemia in CKD: A 28-Day, Phase 2A Randomized Trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67:861–71. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Keith B, Johnson RS, Simon MC. HIF1alpha and HIF2alpha: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Haase VH. Mechanisms of hypoxia responses in renal tissue. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:537–41. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012080855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nangaku M, Rosenberger C, Heyman SN, Eckardt KU. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor in kidney disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;40:148–57. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Haase VH, Hartman CS, Maroni B, Farzaneh-Far R, McCullough PA. Vadadustat—a Novel, Oral Treatment for Anemia of CKD—Maintains Stable Hemoglobin Levels in Dialysis Patients Converting From Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agent (ESA). National Kidney Foundation Spring Clinical Meeting; Boston, MA, U.S.A.. 2016. p Abstract 171. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Haase VH, Khawaja Z, Chan J, Zuraw Q, Farzaneh-Far R, Maroni BJ, et al. Vadadustat Maintains Hemoglobin (Hb) Levels in Dialysis-Dependent Chronic Kidney Disease (DD-CKD) Patients Independent of Systemic Inflammation or Prior Dose of Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agent (ESA) J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:318A. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Akizawa T, Tsubakihara Y, Nangaku M, Endo Y, Nakajima H, Kohno T, et al. Effects of Daprodustat, a Novel Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitor on Anemia Management in Japanese Hemodialysis Subjects. Am J Nephrol. 2017;45:127–35. doi: 10.1159/000454818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.MacDougall IC, Akizawa T, Berns J, Lentini S, Bernhardt T. Molidustat increases hemoglobin in erythropoiesis stimulating agents (ESA) - naive patients with chronic kidney diseases not on dialysis (CKD-ND) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:i16. [Google Scholar]

- 97.MacDougall IC, Akizawa T, Berns J, Bernhardt T, Krüger T. Safety and efficacy of molidustat in erythropoiesis stimulating agenst (ESA) pre-treated anemic patients with chronic kidney disease not on dialysis (CKD-ND) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:i193. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Akizawa T, Hanaki K, Arai M. JTZ-591, an oral novel HIF-PHD inhibitor, elevates hemoglobin in Japanese anemic patients with chronic kidney disease not on dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(Suppl. 3):iii8–iii10. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jain MR, Joharapurkar AA, Pandya V, Patel V, Joshi J, Kshirsagar S, et al. Pharmacological Characterization of ZYAN1, a Novel Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitor for the Treatment of Anemia. Drug Res (Stuttg) 2016;66:107–12. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1554630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Patel H, Joharapurkar AA, Pandya VB, Patel VJ, Kshirsagar SG, Patel P, et al. Influence of acute and chronic kidney failure in rats on the disposition and pharmacokinetics of ZYAN1, a novel prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor, for the treatment of chronic kidney disease-induced anemia. Xenobiotica. 2017:1–8. doi: 10.1080/00498254.2016.1278287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ochiai H, Sato F, Tokuyama S, Kikumori K, Kurimoto F, Takayama N, et al. First-in-Human Study of TP0463518, a Novel Oral Hypoxia Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase (HIF-PH) Inhibitor with Liver-Specific Erythropoietin Secretion. JASN. 2016;27:749A. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Barrett TD, Palomino HL, Brondstetter TI, Kanelakis KC, Wu X, Yan W, et al. Prolyl hydroxylase inhibition corrects functional iron deficiency and inflammation-induced anaemia in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:4078–88. doi: 10.1111/bph.13188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]