Abstract

Personality disorders are defined in the current psychiatric diagnostic system as pervasive, inflexible, and stable patterns of thinking, feeling, behaving, and interacting with others. Questions regarding the validity and reliability of the current personality disorder diagnoses prompted a reconceptualization of personality pathology in the most recent edition of the psychiatric diagnostic manual, in an appendix of emerging models for future study. To evaluate the construct and discriminant validity of the current personality disorder diagnoses, we conducted a quantitative synthesis of the existing empirical research on associations between personality disorders and interpersonal functioning, defined using the interpersonal circumplex model (comprising orthogonal dimensions of agency and communion), as well as functioning in specific relationship domains (parent– child, family, peer, romantic). A comprehensive literature search yielded 127 published and unpublished studies, comprising 2,579 effect sizes. Average effect sizes from 120 separate meta-analyses, corrected for sampling error and measurement unreliability, and aggregated using a random-effects model, indicated that each personality disorder showed a distinct profile of interpersonal style consistent with its characteristic pattern of symptomatic dysfunction; specific relationship domains affected and strength of associations varied for each personality disorder. Overall, results support the construct and discriminant validity of the personality disorders in the current diagnostic manual, as well as the proposed conceptualization that disturbances in self and interpersonal functioning constitute the core of personality pathology. Importantly, however, contradicting both the current and proposed conceptualizations, there was not evidence for pervasive dysfunction across interpersonal situations and relationships.

Keywords: interpersonal circumplex, interpersonal functioning, meta-analysis, personality disorders

Personality disorders are defined in the current psychiatric diagnostic system as characterized by pervasive, inflexible, and stable patterns of thinking, feeling, behaving, and interacting with others that cause significant distress or impaired functioning in interpersonal or professional domains (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). The importance of interpersonal dysfunction in defining personality disorders is clearly evident in their descriptive features and diagnostic criteria— each personality disorder, as defined in the most recent editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–IV; APA, 2000; DSM–5 Section II; APA, 2013), is described by a problematic approach to interpersonal interactions, or by characteristics that are likely to interfere with adaptive interactions and relationships (see Table 1). Given the central role of interpersonal dysfunction for personality disorders, considerable empirical research has sought to characterize the key interpersonal features of personality disorders, in general, as well as of each individual personality disorder. Although studied to a somewhat lesser extent, a growing body of empirical research has also considered associations between personality disorders and the quality of functioning in specific interpersonal relationships, such as with one’s children, parents and siblings, peers, and romantic partners.

Table 1.

Description of DSM Personality Disorders

| Personality disorder | Description |

|---|---|

| Paranoid | Pervasive pattern of distrust and suspiciousness of others |

| Schizoid | Pervasive pattern of detachment from social relationships; restricted range of emotional expression in interpersonal interactions |

| Schizotypal | Pervasive pattern of odd, eccentric behavior or thinking; perceptual distortions; discomfort in interpersonal interactions |

| Antisocial | Pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others |

| Borderline | Pervasive pattern of instability in interpersonal interactions, sense of self, and affect; marked impulsivity |

| Histrionic | Pervasive pattern of excessive yet shallow emotionality and attention-seeking |

| Narcissistic | Pervasive pattern of grandiosity, need for admiration, and lack of empathy |

| Avoidant | Pervasive pattern of inhibition and feelings of inadequacy in interpersonal interactions; hypersensitivity to negative evaluation |

| Dependent | Pervasive and excessive need to be taken care of; dependence on and submission to others |

| Obsessive-Compulsive | Pervasive pattern of preoccupation with orderliness, perfection, morality, and control |

Significant changes to the conceptualization of personality pathology were proposed and are now delineated in the DSM–5 appendix of emerging models for future study; however, both current (DSM–IV, reprinted in DSM–5 Section II) and proposed (DSM–5 Section III) conceptualizations emphasize core disturbances in interpersonal functioning. We conducted a meta-analytic review of empirical research on associations between personality disorders and interpersonal functioning to evaluate (a) the construct and discriminant validity of the existing personality disorder diagnoses, as defined in the DSM–IV and in the main manual of DSM–5 (Section II), as well as (b) the extent to which they reflect pervasive interpersonal dysfunction or impairment that is specific to a subset of relationship types. To do so, we synthesized empirical research conducted over the past 20 years, using the interpersonal circumplex model—which comprises the orthogonal dimensions of agency (dominance vs. submissiveness) and communion (warmth vs. coldness)—to organize the findings of this literature. We also considered (c) whether methodological or sample variables moderated these associations. The results have direct implications for theoretical conceptualizations of personality pathology and for personality science more broadly; will help to determine the features that should be emphasized in personality disorder diagnostic criteria sets; will guide empirical research on mechanisms linking personality disorders and interpersonal functioning; and will provide an empirical basis for future editions of the DSM (see Hopwood, Wright, Ansell, & Pincus, 2013; Ro & Clark, 2009).

DSM Personality Disorders: Controversies and Challenges

The classification of personality disorders has evolved substantially since the DSM was introduced over seven decades ago and continues to be an area of active—and sometimes controversial—research (see Widiger, 2012, for a historical review of personality disorders across DSM editions). Contemporary diagnostic criteria sets for the personality disorders were introduced in DSM–IV (APA, 1994), with the 10 personality disorders organized into three descriptive clusters: Cluster A (“odd-eccentric”) included paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders; Cluster B (“dramatic-emotional-erratic”) included antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders; and Cluster C (“anxious-fearful”) included avoidant, dependent, and obsessive– compulsive personality disorders. In addition, DSM–IV included the diagnosis personality disorder not otherwise specified, given for symptoms indicative of a personality disorder not adequately captured by one of the other personality disorder diagnoses.

A number of important criticisms of the DSM–IV personality disorders (e.g., Clark, 2007; Krueger & Eaton, 2010; Krueger, Skodol, Livesley, Shrout, & Huang, 2007; Trull & Durrett, 2005; Widiger & Samuel, 2005; Widiger, Simonsen, Krueger, Livesley, & Verheul, 2005) prompted calls for major changes to their conceptualization and diagnosis. The DSM–IV personality disorders are conceptualized as 10 dichotomous categories, but evidence that this conceptualization best represents the underlying latent structure of personality pathology is limited (e.g., Clark, 2007; Kotov et al., 2011; Krueger & Eaton, 2010; Widiger & Samuel, 2005). The diagnostic thresholds that determine the presence versus absence of a personality disorder diagnosis have little empirical rationale and do not appear to correspond to clinically significant impairment (Clark, 2007; Spitzer & Wakefield, 1999; Widiger, 2001; Widiger & Trull, 2007). High diagnostic overlap and comorbidity among personality disorder diagnoses also fueled concerns about the validity of the diagnostic categories, as most individuals who meet criteria for one personality disorder also qualify for an additional diagnosis (e.g., Krueger & Markon, 2006). Thus, significant concerns were raised as to the construct validity of the personality disorders as defined in DSM–IV, or the extent to which the personality disorders, as a whole, as well as each specific personality disorder, reflect true psychopathology constructs with meaningful associations with other constructs of relevance. Further concerns have been raised as to their discriminant validity, or the extent to which each personality disorder reflects a discrete diagnostic construct with unique associations relative to the other personality disorders. At the same time, decades of research and several large-scale studies also provide evidence that DSM–IV personality disorders are meaningfully associated with and predict important psychosocial functioning constructs (e.g., Cohen, Crawford, Johnson, & Kasen, 2005; Fergusson, Horwood, & Ridder, 2005; Gunderson et al., 2011; Skodol et al., 2002; Zanarini, Frankenburg, Reich, & Fitzmaurice, 2010).

The decade preceding the publication of DSM–5 saw considerable and varied efforts to address limitations in how personality pathology is defined within the DSM (see Clark, 2007; Krueger & Eaton, 2010; Krueger & Markon, 2014; Widiger, 2013; Widiger & Samuel, 2005). The DSM–5 was intended to promote a “paradigm shift” (Kupfer, First, & Regier, 2008; p. xix): Major revisions and reconceptualizations throughout the DSM, and in particular to the personality disorders, were actively encouraged and solicited (First et al., 2002; Krueger et al., 2007; Widiger et al., 2005). Proposed revisions ran the gamut from relatively minor modifications to the specific diagnostic criteria for each of the personality disorders to a complete revamping of the personality disorder diagnostic classification system. Although many of these proposed revisions had ardent supporters, there were also strident objections, primarily with regard to their nature and scope, as well as a lack of sufficient empirical support for some of the proposed revisions (see Widiger, 2013; Zimmerman, 2012). Ultimately, the APA Board of Trustees elected to retain the original DSM–IV diagnostic criteria for personality disorders (but not the personality disorder clusters) in the main manual of DSM–5 (Section II). However, a new hybrid dimensional-categorical model proposed by the Personality and Personality Disorders Work Group was also included in the DSM– 5’s appendix of emerging measures and models for further study (Section III).

In the proposed hybrid model, a personality disorder diagnosis is made in the presence of significant problems in personality (self and interpersonal) functioning, and specific patterns of pathological personality traits, delineated using five broad traits of personality (Negative Affectivity vs. Emotional Stability, Detachment vs. Extraversion, Antagonism vs. Agreeableness, Disinhibition vs. Compulsivity, Psychoticism vs. Lucidity) that can in turn be further specified using 25 specific maladaptive trait facets. Problems in personality functioning are defined in terms of how an individual typically experiences himself/herself or others: impairments in “self” functioning include issues with identity, self-concept, self-direction, and agentic behavior, whereas impairments in “interpersonal” functioning include issues with interpersonal relatedness, intimacy, empathy, and communal behavior. DSM–5 Section III retains six proposed personality disorder types: schizotypal, antisocial, borderline, narcissistic, avoidant, and obsessive– compulsive personality disorders, each defined by a specific pattern of impairment in personality functioning and traits. In addition, a diagnosis of personality disorder—trait specified is given in the presence of impaired personality functioning that does not fully meet criteria for a specific personality disorder type.

Although the proposed hybrid model was ultimately not adopted for the DSM–5’s main manual, its inclusion in the Section III appendix of emerging models for further study encourages research on its alternative conceptualization of personality pathology. Of particular interest is research that evaluates the construct validity of the DSM–5 Section III proposed definition of personality pathology, including associations with indicators of psychosocial functioning (Clark, 2007; Hopwood, Wright, et al., 2013; Widiger, Simonsen, et al., 2005). Germane are recent efforts toward greater integration of research on psychopathology symptoms, personality traits, and psychosocial functioning, with growing evidence of overlap between personality pathology and functioning in important psychosocial domains, including in interpersonal relationships (see Clark & Ro, 2014; Ro & Clark, 2013). Thus, examination of interpersonal functioning among individuals with personality disorders and symptoms, as defined in DSM–IV and the main manual of DSM–5 (Section II), offers an important test of the construct validity of each of the current personality disorder diagnoses. In addition, as reviewed below, the core features of DSM–5 Section III personality disorders—impairment in self and interpersonal functioning—are remarkably well aligned with the core dimensions described in interpersonal circumplex models (see Hopwood, Wright, et al., 2013). Thus, examining interpersonal functioning as conceptualized using the interpersonal circumplex model offers an important test of the construct validity of personality disorders defined using DSM–IV and the main manual of DSM–5 Section II, as well as the proposed DSM–5 Section III classification system for personality pathology.

Moreover, because both the current (DSM–IV and DSM–5 Section II) and proposed (DSM–5 Section III) diagnoses emphasize the pervasiveness of dysfunction across relationship types and interaction partners, examining interpersonal functioning for personality disorders across specific relationship domains indicates the extent to which interpersonal dysfunction is evident across relationships or is specific to a subset of relationship types, thus providing a test of the construct validity of both the current and proposed classification systems. Models emphasizing pervasiveness of dysfunction across relationship contexts (as do both the current and proposed DSM models) are consistent with conceptualizing interpersonal dysfunction as a trait-like construct that individuals “carry” with them across their different relationships. By contrast, evidence of differences in the presence and type of interpersonal dysfunction across different relationships would underscore the need for conceptual and etiological models of interpersonal dysfunction in personality pathology to account for this heterogeneity by considering such features as relationship partners, relationship quality, role demands, and other individual and systemic influences.

Interpersonal Functioning: Implications for Personality Disorder Theory and Research

Interpersonal style is defined by one’s characteristic approach to interpersonal situations and relationships, and includes attitudes toward, behaviors in, and goals for relationships; cognitions about the meaning of relationships; affect and behavior in interpersonal interactions; and interpretation of others’ interaction behaviors. Along with other factors, one’s characteristic interpersonal style determines the quality of functioning in specific relationship domains, including with one’s children, parents and siblings, peers, and romantic partners.

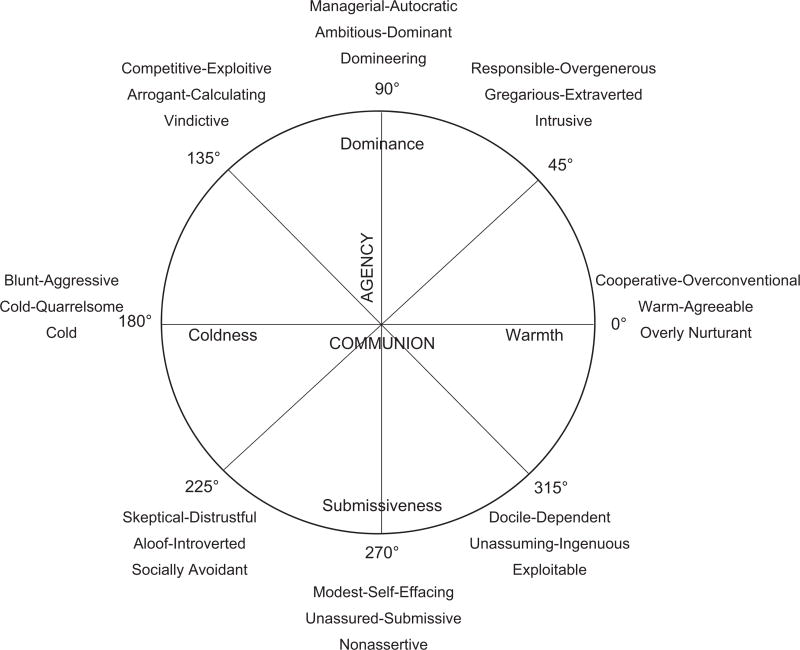

Interpersonal theory emphasizes the integral role of interpersonal relationships and experiences with others for broader aspects of psychosocial functioning, and is rooted in the assumption that all interpersonal interactions reflect attempts to establish and maintain self-esteem or avoid anxiety (Leary, 1957; Sullivan, 1953). The means by which an individual accomplishes these fundamental goals is apparent in a durable set of techniques that are observable in any interpersonal situation, from brief interactions to enduring relationships. Interpersonal theory is comprised of three major principles: complementarity, vector length, and circumplex structure. The principle of complementarity, or reciprocity, posits that an individual’s interpersonal behaviors tend to initiate and elicit interpersonal responses from his or her interaction partner that reinforce the individual’s original behaviors; importantly, these responses tend to be restricted to a relatively narrow range of interpersonal reactions that are both reciprocal and correspondent: dominance tends to provoke its reciprocal response of submissiveness (and vice versa, with submissiveness provoking dominance), whereas coldness/hostility and warmth/friendliness tend to provoke their corresponding responses (Carson, 1969; Kiesler, 1983; Leary, 1957; Markey, Funder, & Ozer, 2003). The principal of vector length, or amplitude, posits that statistical deviance from a point of origin is an index of the extremity of an individual’s interpersonal behaviors; vector length can also be thought of as the degree of differentiation within an interpersonal profile (Gurtman & Balakrishnan, 1998; Gurtman & Pincus, 2003; Leary, 1957). Finally, the principle of circumplex structure posits that variables in the interpersonal domain are arranged in a two-dimensional, circular space referred to as a “circumplex,” which is defined by two orthogonal, bipolar interpersonal dimensions, agency (dominance vs. submissiveness) and communion (warmth vs. coldness, also referred to as hostility or hate vs. friendliness or love); this circumplex space is further subdivided into eight equal segments that form progressive blends of the agency and communion dimensions (see Figure 1; Acton & Revelle, 2002; Leary, 1957; Wiggins & Trobst, 1997).

Figure 1.

Theoretical circumplex structure of interpersonal behavior, with octants reflecting eight interpersonal traits with subscale names for common interpersonal circumplex measures.

The circumplex model of interpersonal style provides a means of conceptualizing, organizing, and assessing individuals’ and groups’ characteristic approach toward interpersonal interactions. Several circumplex measures of interpersonal behavior, goals, and values have been developed, including those that reflect more normative aspects of interpersonal style and those that tap into more problematic aspects. These include the Interpersonal Checklist (ICL; LaForge & Suczek, 1955), Interpersonal Adjective Scales (IAS; Wiggins, 1979) and Revised Interpersonal Adjective Scales (IAS-R; Wiggins, Trapnell, & Phillips, 1988), Inventory of Interpersonal Problems— Circumplex (Alden, Wiggins, & Pincus, 1990), Octant Scale Impact Message Inventory (IMI-C; Schmidt, Wagner, & Kiesler, 1999), Person’s Relating to Others Questionnaire (PROQ; Birtchnell, Falkowski, & Steffert, 1992) and Person’s Relating to Others Questionnaire—Revised (PROQ2; Birtchnell & Evans, 2004; Birtchnell & Shine, 2000), Chart of Interpersonal Reactions in Closed Living Environments (CIRCLE; Blackburn & Renwick, 1996), Inventory of Interpersonal Goals (IIG; Horowitz, Dryer, & Krasnoperova, 1997), Support Actions Scale—Circumplex (SAS-C; Trobst, 2000), and Circumplex Scales of Interpersonal Values (CSIV; Locke, 2000). Although the names of the subscales for each measure vary, each is defined by the two orthogonal interpersonal dimensions of agency and communion, with the circumplex space divided into octants that reflect specific interpersonal traits. Depending on the measure, these octants reflect interpersonal traits that are relatively normative, such as the Managerial-Autocratic, Competitive-Exploitive, Blunt-Aggressive, Skeptical-Distrustful, Modest-Self-Effacing, Docile-Dependent, Cooperative-Overconventional, and Responsible-Overgenerous subscales of the ICL, or are more problematic and excessive, such as the Domineering, Vindictive, Cold, Socially Avoidant, Nonassertive, Exploitable, Overly Nurturant, and Intrusive subscales of the IIP-C (see Table 2 for a description of the interpersonal traits assessed by the IIP-C).

Table 2.

Descriptions of Maladaptive Interpersonal Traits in the Interpersonal Circumplex

| Interpersonal style | Description |

|---|---|

| Domineering | Tendency to control, manipulate, be aggressive toward, or try to change others |

| Vindictive | Tendency toward distrust and suspicion of others; an inability to care about the needs and happiness of others |

| Cold | Tendency to have difficulty expressing affection toward or feeling love for others; an inability to be generous to, get along with, or forgive others |

| Socially Avoidant | Tendency to feel anxious and embarrassed with others; difficulty expressing feelings and socializing with others |

| Nonassertive | Tendency to have difficulty expressing needs, acting authoritatively, or being firm and assertive with others |

| Exploitable | Tendency to have difficulty feeling and expressing anger to others; gullible and easily taken advantage of by others |

| Overly Nurturant | Tendency to try to please others; overly generous to, trusting of, caring toward, and permissive of others |

| Intrusive | Tendency toward inappropriate self-disclosure and attention-seeking; difficulty being alone |

Interpersonal circumplex measures have demonstrated both reliability and validity, lending empirical support to the theoretical circumplex model. Numerous studies have reported at least adequate internal consistency for the most commonly used interpersonal circumplex measures (e.g., Alden et al., 1990; Vittengl, Clark, & Jarrett, 2003; Wilson, Revelle, Stroud, & Durbin, 2013), as well as good test–retest reliability (Horowitz, Rosenberg, Baer, Ureño, & Villaseñor, 1988; Monsen, Hagtvet, Havik, & Eilertsen, 2006). Acton and Revelle (2002) examined the structure of the ICL, IAS and IAS-R, IIP-C, and IIG, and found that each showed the expected circumplex structure, with constant radius, equal spacing, and no preferred rotation. Evidence of construct validity also comes from a growing body of empirical research demonstrating that interpersonal style shows meaningful associations with interpersonal interactions and the quality of interpersonal relationships (e.g., Lawson, 2008; Saffrey, Bartholomew, Scharfe, Henderson, & Koopman, 2003; Stroud, Durbin, Saigal, & Knobloch-Fedders, 2010; Wilson et al., 2013).

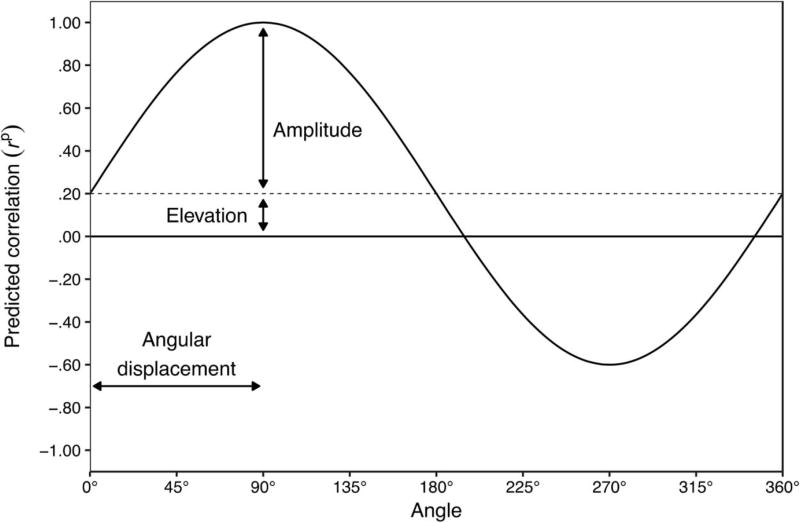

In addition to indexing interpersonal traits, the interpersonal circumplex model offers a powerful representation of an individual’s or group’s interpersonal style in the form of interpersonal “profiles” (see Gurtman, 2009). In an interpersonal profile, scores on the eight octants of the circumplex are presented visually, either in a polar coordinate system (i.e., the circumplex) or arranged linearly across the eight interpersonal traits; the ordering of the scores reflects their theoretical arrangement on the circumplex. Because interpersonal profiles produced using circumplex measures tend to be sinusoidal in form, they can be modeled against the prototypical cosine function (see Gurtman, 1992; Gurtman & Balakrishnan, 1998; Gurtman & Pincus, 2003; Wright, Pincus, Conroy, & Hilsenroth, 2009; Zimmermann & Wright, 2017; see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Theoretical interpersonal circumplex profile. Structural summary parameters for the predicted correlations between interpersonal traits and an external construct include elevation (the average correlation with interpersonal style), amplitude (difference between the average correlation and the peak correlation of the profile), and angular displacement (the angular distance from 0° to the peak correlation of the profile).

Applying this structural summary method yields parameters useful for characterizing both individuals and groups. For an individual’s profile, elevation is the mean level on the profile; amplitude (mathematically equivalent to vector length) is the difference between the mean level and the peak value of the profile; and angular displacement is the angular distance from 0° to the peak value of the profile. Elevation reflects an individual’s idiosyncratic response style, or, in the presence of a general factor underlying the specific scales of the interpersonal circumplex measure (e.g., Tracey, Rounds, & Gurtman, 1996; Vittengl et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2013), the individual’s level on that general factor. Amplitude reflects the extent to which an individual’s profile shows little differentiation, characterized by comparable values across each interpersonal trait, or a differentiated pattern, characterized by a single peak value on a particular interpersonal trait. Angular displacement reflects the predominant interpersonal theme for an individual. Similar logic can be applied to interpersonal profiles for groups—to the extent that another construct is characterized by interpersonal content, associations with an interpersonal circumplex measure should form the expected sinusoidal wave (see Gurtman, 1992; Gurtman & Balakrishnan, 1998; Gurtman & Pincus, 2003; Wright et al., 2009; Zimmermann & Wright, 2017). For group profiles, elevation is the average correlation with interpersonal style; amplitude is the difference between the average correlation and the peak correlation of the profile; and angular displacement is the angular distance from 0° to the peak correlation of the profile. As for individuals, elevation reflects the group’s idiosyncratic response style or its association with a general factor; amplitude reflects the differentiation of the group; and angular displacement reflects the predominant interpersonal theme for the group. In addition to these three structural parameters, the structural summary method also yields a goodness-of-fit statistic, R2, that can be used to determine how well the individual or group profile fits the expected pattern. Interpersonal profiles can, thus, provide a rich representation of the predominant interpersonal style that characterizes an individual or group, as well as the extent to which this style is defined by differentiated interpersonal behaviors.

The importance of interpersonal style and the utility of interpersonal profiles can be readily appreciated in the study of personality disorders. As defined in the current DSM classification system, each personality disorder is characterized by interpersonal dysfunction, but each also demonstrates its own specific “flavor” of pathology. Moreover, to the extent that each personality disorder shows a unique pattern of dysfunction, each is expected to show a unique interpersonal style, indexed by high amplitudes and different angular displacements relative to other personality disorders. Thus, organizing interpersonal functioning using the interpersonal circumplex model offers a valuable and informative approach to evaluating the construct and discriminant validity of the personality disorders.

Personality Disorders and Problems in Interpersonal Functioning: Empirical Research

Several researchers have suggested that personality disorders are fundamentally disorders of relating with others (e.g., Benjamin, 1993; Hopwood, Wright, et al., 2013; Kiesler, 1983); this conceptualization is reflected in the definition of personality pathology proposed in DSM–5 Section III (APA, 2013). Much of the empirical research on personality disorders and interpersonal functioning has considered associations with interpersonal style, assessed using interpersonal circumplex measures (see Pincus & Gurtman, 2006; Widiger & Hagemoser, 1997, for reviews). There is remarkable consistency across different methods of assessing personality disorders and interpersonal style, different interpersonal circumplex measures, and among clinical and nonclinical samples in placement for most of the personality disorders within the interpersonal circumplex. Several recent studies using DSM–IV personality disorder criteria (see Haslam, Reichert, & Fiske, 2002; Locke, 2000; Monsen et al., 2006; Pagan, Eaton, Turkheimer, & Oltmanns, 2006) have shown that paranoid and antisocial personality disorders consistently show their highest associations with dominant and dominant-cold traits (i.e., Vindictive, Cold, and Domineering subscales of the IIP-C), whereas schizoid personality disorder consistently shows its highest associations with cold and submissive-cold traits (i.e., Cold and Socially Avoidant subscales of the IIP-C) and avoidant personality disorder consistently shows its highest associations with cold-submissive traits (i.e., Socially Avoidant, Nonassertive, and Cold subscales of the IIP-C). By contrast, histrionic and narcissistic personality disorders consistently show their highest associations with dominant and dominant-warm traits (i.e., Intrusive, Domineering, and Vindictive subscales of the IIP-C), whereas dependent personality disorder consistently shows its highest associations with submissive and submissive-warm traits (i.e., Nonassertive, Exploitable, and Overly Nurturant subscales of the IIP-C). However, there have also been some inconsistencies in this literature—schizotypal, borderline, and obsessive– compulsive personality disorders have shown both generally large associations or a general lack of associations with IIP-C subscales (see Haslam et al., 2002; Locke, 2000; Pagan et al., 2006)—indicating that not all of the personality disorders have yet been consistently located in the interpersonal circumplex space. There have also been examinations of associations between personality disorders and functioning within specific relationship domains, in addition to empirical research on associations with interpersonal style. A review of this research indicates that, as expected, personality disorders are associated with dysfunction in important relationship domains, including with one’s children, family, peers, and romantic partners (e.g., Oltmanns, Melley, & Turkheimer, 2002; Skodol et al., 2002; Wilson & Durbin, 2012).

Thus, a qualitative assessment of previous research indicates that personality disorders are associated with interpersonal dysfunction, as evidenced by associations with problematic interpersonal styles and impairment in specific relationship domains. As such, the existing research provides some evidence of the construct validity of the current classification system for personality disorders. However, a number of questions remain, many of which can be more definitively addressed through the systematic quantitative synthesis of relevant data in a meta-analytic review. First, although there is general consensus of the predominant interpersonal style for many personality disorders, for others, this remains unclear. Meta-analysis allows for the derivation of effect size estimates for associations between personality disorders and each trait in the interpersonal circumplex. This, in turn, allows for examination of interpersonal profiles for each personality disorder that can be summarized using the structural parameters of elevation (average correlation with interpersonal style), amplitude (peak correlation of the profile), and angular displacement (angular distance from 0° to the peak correlation). Second, although there is evidence that personality disorders are associated with dysfunction in specific relationship domains, it is unclear whether some personality disorders show greater dysfunction than others, and to what extent dysfunction is pervasive across all relationship domains or is specific to particular domains. By including all available relevant data, meta-analysis yields a comprehensive set of effect sizes for each personality disorder for functioning in the different relationship domains. Third, some personality disorders and some relationship domains are more highly represented in the published literature than others. The inclusion of unpublished data, including relevant dissertations and data sets from researchers, may yield additional information for domains that are less frequently reported in the published literature, thereby giving a more accurate representation of true effect sizes. Fourth, there is considerable variability in the existing data in study design, the methods used to assess personality disorders and interpersonal functioning, and sample characteristics—these issues can be addressed in meta-analysis by correcting for sampling error and measurement unreliability and by conducting moderator analyses that stratify effect sizes as a function of study, methodological, and sample characteristics. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to examine associations between personality disorders and interpersonal functioning (but see Lazarus, Cheavens, Festa, & Rosenthal, 2014, for a qualitative review of borderline personality disorder and interpersonal functioning assessed using behavioral and laboratory measures).

The Present Meta-Analytic Review

The present meta-analytic review provides a test of the construct and discriminant validity of personality disorders, as they are conceptualized in the current psychiatric diagnostic classification system (DSM–IV and DSM–5 Section II). It also tests the extent to which personality disorders are defined by disturbances in self and interpersonal functioning, as conceptualized in the proposed classification system (DSM–5 Section III). We conducted a series of meta-analyses that examined associations between personality disorder diagnoses and symptoms and (a) interpersonal style, defined using the interpersonal circumplex, and (b) functioning in specific relationship domains, including the parent– child, family, peer, and romantic domains. We expected that personality disorders would be generally associated with interpersonal dysfunction, as evidenced by moderate-to-strong associations with maladaptive interpersonal traits and impaired functioning in specific relationship domains—that is, the construct validity of the personality disorders, as a whole, and of each specific personality disorder, would be supported. Moreover, we expected that each personality disorder would show a predominant interpersonal style, indexed by amplitude and angular displacement—that is, the discriminant validity of each personality disorder would be supported. We further expected that the personality disorders would show pervasive impairment across specific relationship domains, as emphasized in both the current and proposed DSM conceptualizations of personality pathology. Our examination of potential methodological and sample variables, including the method used to assess personality disorders and interpersonal functioning constructs, and sample age, sex, and type, was exploratory.

Personality Disorders

We defined personality disorders using the current DSM taxonomy, that is a DSM–IV (reprinted in DSM–5 Section II) diagnosis of personality disorder, a symptom count of DSM–IV criteria, or a questionnaire or rating scale of symptoms consistent with DSM–IV criteria. Although the personality disorder constructs defined in DSM–IV are fundamentally the same as those in DSM–III–R, there were sufficient changes to the specific diagnostic criteria sets (e.g., substantive changes in the wording of specific criteria; dropping or adding criteria; changes to the number of criteria needed for a diagnosis) to introduce potentially meaningful variability in effects assessed using the different editions; thus, we limited our literature search to research published after 1994, when DSM–IV was published. Notably, because the diagnostic criteria for personality disorders in DSM–5 are identical to those in DSM–IV, the results of our meta-analysis for DSM–IV personality disorders are directly applicable to the current DSM–5 Section II (main manual) personality disorders. Although nomenclatures and personality pathology constructs other than those found in the DSM exist, some of which with strong theoretical underpinnings and empirical support (e.g., borderline personality organization; Kernberg, 1967), and some older instruments developed to assess pre-DSM–IV personality disorder constructs have been widely used (e.g., Narcissistic Personality Inventory; Raskin & Hall, 1979), we limited our meta-analysis to DSM–IV personality disorders to maximize comparability in personality disorder constructs across studies and because the DSM–IV personality disorder diagnostic criteria sets are exactly the same as those for DSM–5. Our focus on DSM diagnoses and symptoms meant that we excluded some widely studied and related constructs, including psychopathy, antisocial behavior, and conduct problems. Although psychopathy shows overlap with antisocial personality disorder, it includes several interpersonal and affective features not in the current DSM diagnostic criteria (Cleckley, 1976). Antisocial behavior and conduct problems are typically defined quite broadly (e.g., substance use, gambling, risky sex, impulsivity, callousness), often with considerable variation across studies, and, thus, do not necessarily reflect antisocial personality disorder and conduct disorder diagnostic criteria, respectively. In addition, because we were interested in examining the specificity of effects for each of the 10 personality disorders, we excluded studies that presented results for the presence versus absence of any personality disorder, a symptom count across different personality disorders, or personality disorder clusters.

Interpersonal Functioning

We defined interpersonal style using circumplex models of interpersonal functioning. We selected the circumplex model based on its rich theoretical history (Leary, 1957; Sullivan, 1953), strong empirical support (Acton & Revelle, 2002; Alden et al., 1990; Horowitz et al., 1988), and direct relevance to DSM–5 Section III personality pathology (Hopwood, Wright, et al., 2013). Interpersonal circumplex models include two orthogonal, bipolar dimensions defined by agency (dominance vs. submissiveness) and communion (warmth vs. coldness), but there is variation in the terms used to describe the eight interpersonal traits that comprise the circumplex depending on the specific nature of the interpersonal circumplex measure, with labels reflecting both normative and problematic aspects of interpersonal style (see Figure 1). Because of our interest in the more extreme, pathological aspects of interpersonal functioning, we refer to all interpersonal traits using subscale names from the IIP-C, namely Domineering, Vindictive, Cold, Socially Avoidant, Nonassertive, Exploitable, Overly Nurturant, and Intrusive (see Table 2). We selected the parent– child, family, peer, and romantic domains for our examination of functioning in specific relationship domains because of the importance of these domains for the vast majority of people. Given our interest in current functioning within these domains, we excluded studies that used retrospective reports of relationship functioning, including experiences of the family of origin, or studies that did not include assessment of personality disorders and interpersonal functioning in close temporal proximity to one another. Because we were interested in examining the specificity of effects for each interpersonal trait or relationship domain, we excluded studies that presented results for the sum or average across different interpersonal traits (e.g., total interpersonal problems), or for general interpersonal functioning not defined to a particular relationship domain (e.g., social skills).

Moderator Analyses

We considered several potential methodological and sample moderators of associations between personality disorders and interpersonal functioning, including the method used to assess personality disorders and interpersonal functioning, and sample age, sex, and type.

Assessment of personality disorders and interpersonal functioning

We conducted moderator analyses that compared associations between personality disorders and interpersonal functioning assessed using self-report methods to those assessed using other methods (structured interviews, unstructured interviews, informant reports, observational ratings, archives/records). A majority of the literature has relied on self-report questionnaires; (semi-) structured diagnostic interviews are also frequently used to assess personality disorders. Other less commonly used methods include unstructured clinician interviews, informant reports, observational ratings, and archives/records (e.g., hospital or arrest records). Self-report questionnaires have the advantages of being easily administered and useful for obtaining individuals’ own perspectives on their symptoms, behavior, and relationships. However, they rarely assess the stability and long-standing nature of personality disorder symptoms, nor do they typically assess whether symptoms are accompanied by clinically significant impairment or distress, both key criteria for a personality disorder diagnosis; as such, they are not appropriate for use as diagnostic instruments. Structured diagnostic interviews, on the other hand, are developed specifically to assess personality disorders according to diagnostic criteria; their use facilitates the systematic, comprehensive, replicable, and objective assessment of personality disorders (see Trull, Carpenter, & Widiger, 2013; Widiger & Coker, 2002). Though widely used in clinical contexts, unstructured clinical interviews are less common in research because they are often idiosyncratic, noncomprehensive, unreliable, and subjective (Trull et al., 2013).

Self-report questionnaires tend to yield dramatically higher prevalence rates of personality disorders relative to structured interviews (Clark & Harrison, 2001; Kaye & Shea, 2000; Westen, 1997; Zimmerman, 1994). Although structured diagnostic interviews rely on self-reports of symptoms and behaviors, unlike for self-report questionnaires, the interviewer has opportunities to ensure accuracy through the use of open-ended and indirect questioning and follow-up questioning, as well as observations throughout the interview. Informant reports from family, close friends, and acquaintances, observational ratings based on samples of behavior, and information obtained through archives/records also circumvent potential issues related to self-report, and have considerable potential for providing an alternative perspective or objective status. These methods may be particularly useful for individuals with personality disorders, who may show a lack of insight into their own symptoms and behaviors, and for assessing these constructs in general, as they tend to be affected less by social desirability effects than self-reports. Evidence from moderator analyses of weaker associations between personality disorders and interpersonal dysfunction when personality disorders or interpersonal functioning are assessed using self-reports would be consistent with a lack of insight and/or a positive reporting bias associated with a personality disorder.

Sample age

We conducted moderator analyses that compared associations between personality disorders and interpersonal functioning among samples of adults (18 years and older) with those assessed among samples of children and adolescents (younger than 18 years). To comprehensively include personality disorders assessed among samples of children, adolescents, and adults, we included each of the 10 personality disorders, plus conduct disorder. A DSM–IV (and DSM–5 Section II) personality disorder diagnosis requires that the onset of symptoms occurred prior to adolescence or early adulthood. However, the DSM cautions that a personality disorder diagnosis should not typically be given prior to age 18, primarily because of concerns that personality may change considerably through childhood and adolescence and into adulthood. Nonetheless, a growing body of research indicates that personality pathology in adolescence deviates from normative personality development, and that personality disorders diagnosed in adolescence are reliable and valid (e.g., Durrett & Westen, 2005; Levy et al., 1999; Skodol, Johnson, Cohen, Sneed, & Crawford, 2007). Studies of personality disorders and symptoms in children and adolescents typically apply adult criteria without modifications. The one exception is that of antisocial personality disorder, which can only be diagnosed after age 18; prior to that, the persistent pattern of rule and norm violation seen in antisocial personality disorder is instead considered under a conduct disorder diagnosis. Evidence from moderator analyses of comparable associations between personality disorders and interpersonal dysfunction in samples of children/adolescents and adults would speak to the validity of personality pathology across these developmental stages.

Sample sex

We conducted moderator analyses that compared associations between personality disorders and interpersonal functioning assessed among predominately male to those assessed among predominately female samples. There is some evidence that certain personality disorders (schizoid, antisocial, and narcissistic personality disorders) are more commonly diagnosed among males, whereas others (paranoid, borderline, histrionic, avoidant, dependent, and obsessive– compulsive personality disorders) are more commonly diagnosed among females (Trull, Jahng, Tomko, Wood, & Sher, 2010; but see also Lenzenweger, Lane, Loranger, & Kessler, 2007). Sex differences in diagnoses may reflect actual sex differences in prevalence rates, but may also reflect stereotypical views of typical gender roles and behaviors and/or gender bias in assessment (Garb, 1997; Jane, Oltmanns, South, & Turkheimer, 2007; Lindsay & Widiger, 1995). Evidence from moderator analyses of comparable associations between personality disorders and interpersonal dysfunction among males and females would suggest that personality pathology is similarly manifested in the interpersonal domain for males and females, whereas different associations would suggest that personality pathology is differentially associated with interpersonal functioning for males versus females.

Sample type

We conducted moderator analyses that compared associations between personality disorders and interpersonal functioning assessed among nonclinical and those assessed among clinical samples. Many studies examine clinical populations, typically drawn from psychiatric (e.g., inpatients and outpatients in hospitals and mental health clinics) and forensic settings (e.g., juvenile detention, court-mandated domestic violence treatment centers). Although these samples are likely to show more severe personality pathology, there is also the possibility of ascertainment bias and/or systematic differences in treatment-seeking samples (e.g., Corbitt & Widiger, 1995). Other studies examine nonclinical populations, typically university students, as well as individuals in community and school settings. These samples likely show greater variability but generally less severity of personality pathology than clinical samples. Evidence from moderator analyses of stronger associations between personality disorders and interpersonal dysfunction among clinical samples would suggest that more severe personality pathology is associated with comparably greater impairment in the interpersonal domain.

Effect Size Statistics

Because we conceptualize personality pathology and interpersonal functioning as dimensional constructs, we selected Pearson’s r as our index of the association between personality disorders and interpersonal functioning (see Schmidt & Hunter, 2014). The r statistic reflects the amount of overlapping variance among personality disorders and interpersonal functioning constructs. Although r is reduced when comparing groups (e.g., personality disorder vs. no disorder) with unequal sample sizes, the majority of studies included in the present meta-analysis used continuous personality disorder and interpersonal functioning variables. Thus, we considered this to be the most appropriate statistic for the questions of interest examined in the present meta-analysis.

Method

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were (a) assessment of one or more of the personality disorders included in the DSM–IV (and in DSM–5 Section II; schizoid personality disorder, schizotypal personality disorder, paranoid personality disorder, antisocial personality/conduct disorder, histrionic personality disorder, narcissistic personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, avoidant personality disorder, dependent personality disorder, obsessive– compulsive personality disorder diagnoses or symptom counts); (b) assessment of interpersonal functioning (interpersonal traits measured using a circumplex measure of interpersonal style; functioning within the parent– child, family [parent, sibling, extended family], peer, or romantic relationship domains); and (c) sufficient information given for calculating study effect sizes (e.g., correlation between personality disorder symptom count and interpersonal functioning variables, means and standard deviations of interpersonal functioning variables in the personality disorder group and a comparison group), provided either in the published study or dissertation or by the study authors upon request.

Exclusion criteria were (a) effect sizes calculated for (a1) personality disorder diagnoses or symptoms combined across personality disorder categories (e.g., diagnostic criteria met for any personality disorder, a total personality disorder symptom count), rather than for specific personality disorders; (a2) personality diagnoses or symptoms defined using non-DSM–IV (and DSM–5 Section II) diagnostic criteria (e.g., an earlier diagnostic classification system; other personality disorder conceptualizations not aligned with DSM–IV criteria, such as borderline personality organization, Kernberg, 1967); (a3) psychopathy, antisocial behavior, or conduct problems more broadly defined; (b) studies without an appropriate control or comparison group; (c) case studies or studies with fewer than 10 participants total; (d) longitudinal assessment of personality disorders and interpersonal functioning (i.e., not in close temporal proximity to one another) or assessment of interpersonal functioning prior to the assessment of personality disorders (e.g., experiences in the family of origin); and (e) insufficient information given for calculating effect sizes (e.g., beta weights from multiple regression analyses) and we were unable to obtain the relevant data from the study authors.

Literature Search

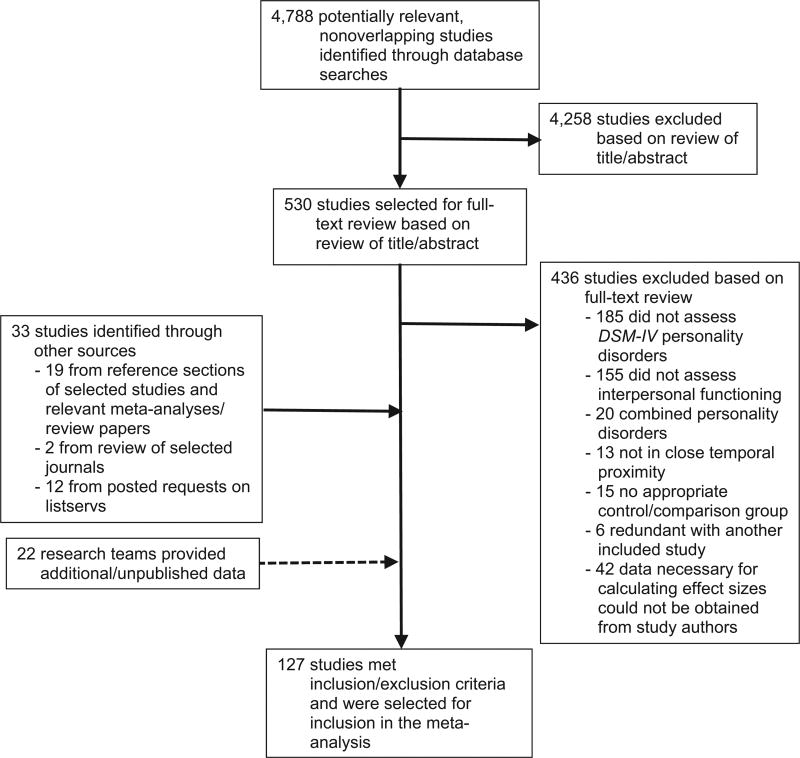

Studies were obtained using multiple search strategies, including (a) searches using three online databases (PsycINFO, Medline, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses) for relevant empirical studies; (b) examination of reference sections in the studies selected for inclusion in the meta-analysis; (c) examination of reference sections in relevant review articles and meta-analyses, obtained using searches of PsycINFO and Medline; (d) examination of all articles published in relevant journals during the relevant time period; (e) posted requests for published and unpublished data on relevant listservs; and (f) contact with research teams to obtain additional data for published reports and/or unpublished data. An overview of the literature search is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flow diagram for the literature search.

Keywords used in the PsycINFO, Medline, and ProQuest database searches included combinations of personality disorder search terms (personality disorder, schizoid personality disorder, schizotypal personality disorder, paranoid personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, conduct disorder, histrionic personality disorder, narcissistic personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, avoidant personality disorder, dependent personality disorder, or obsessive– compulsive personality disorder) with interpersonal functioning search terms (interpersonal, domineering, vindictive, cold, socially avoidant, nonassertive, exploitable, overly nurturant, intrusive, marital relation*, romantic relation*, parent- [or mother- or father-] child relation*, parenting, sibling relation*, family relation*, peer relation*, or friend*). The search was limited to journal articles and dissertations published in the English language between January 1994 (the publication year of DSM–IV) and December 2013.

These database searches yielded 4,788 nonoverlapping abstracts. Titles and abstracts for all potentially eligible studies were reviewed, and 4,258 studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The full text of the remaining 530 studies was then reviewed. In addition, we examined reference sections for all studies selected for inclusion in the meta-analytic review, as well as reference sections from relevant review articles and meta-analyses, obtained using searches of PsycINFO and Medline (the above personality disorder and interpersonal functioning search terms in combination with the terms meta-analysis, literature review, or systematic review, limited to the English language and published after January 1994 through the search date in August, 2014). We also examined all articles published between January 1994 and December 2013 in Journal of Abnormal Psychology ; Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease ; Journal of Personality ; Journal of Personality Assessment ; Journal of Personality Disorders ; and Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, and posted requests for published and unpublished data on 4 listservs (Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Society for Research in Psychopathology, and Society for a Science of Clinical Psychology). These search efforts yielded an additional 33 studies or unpublished data sets that met inclusion criteria. Of the 563 studies that underwent full-text review, 436 were excluded. Studies were excluded because they did not assess DSM–IV personality disorder symptoms or diagnoses (k = 185) or interpersonal functioning (interpersonal traits measured using a circumplex measure of interpersonal style or functioning within the parent– child, family, peer, or romantic domains; k = 155); they reported data for personality disorders combined across personality disorder categories or clusters (k = 20); personality disorders and interpersonal functioning were not assessed in close temporal proximity to one another (k = 13); they did not include an appropriate control or comparison group (k = 15); they reported data that were redundant with that reported in another included study (k = 6); or information necessary for calculating effect sizes was not reported and we were unable to obtain the relevant data from the study authors (k = 42). Finally, we contacted 60 research teams requesting additional data necessary for the computation of effect sizes; 22 study authors provided additional or unpublished data that were included in the meta-analysis. All told, these search efforts yielded 127 studies and unpublished data sets that met inclusion criteria and were selected for inclusion in the meta-analytic review.

Study Coding

Studies that met inclusion criteria were coded for the following: (a) personality disorder and interpersonal functioning information, (b) descriptive study information and sample characteristics, and (c) data for the calculation of effect sizes. All studies were coded by the first author (S. W.), and 25% of randomly selected studies were second coded by the second author (C. B. S.) to assess reliability of study coding. Interrater reliability coefficients (kappas for categorical variables, intraclass correlation coefficients [ICCs] for continuous variables) for the first coding pass are provided below; following conventional guidelines, kappas greater than .75 and ICCs greater than .90 reflect excellent agreement beyond chance, kappas between .40 and .75 and ICCs between .50 and .90 reflect good-to-fair agreement, and kappas less than .40 and ICCs less than .50 reflect poor agreement (Fleiss, 1981; Mitchell, 1979); any coding disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus. An overview of all included studies and unpublished data sets, study characteristics, and study effect sizes is given in Appendix A (interpersonal style) and Appendix B (specific relationship domains).

Personality disorder constructs

Information coded for personality disorders included the personality disorder(s) assessed (κ = 1.00); the method by which personality disorders were assessed, coded as self-report or other (structured clinician interview, unstructured clinician interview, informant report, observational, archives/records; κ = .95); the specific personality disorder measure(s) used (κ = 1.00); and reliability coefficients (interrater reliability: kappa, intraclass correlation coefficient, correlation coefficient, percentage agreement; internal consistency: alpha) for the personality disorder measure (ICC = .96).

Interpersonal functioning constructs

Information coded for interpersonal functioning included a description of the interpersonal functioning construct(s) assessed; the interpersonal functioning domain (interpersonal style; quality of functioning in parent– child, family, peer, or romantic domains; κ = 1.00); the method by which interpersonal functioning was assessed, coded as self-report or other (clinician interview, informant report, observational, archives/ records, experimental/laboratory; κ = .84); the specific interpersonal functioning measure(s) used (κ = 1.00); and reliability coefficients (interrater reliability: kappa, intraclass correlation coefficient, correlation coefficient, percentage agreement; internal consistency: alpha) for the interpersonal functioning measure (κ = .99).

Study information

Descriptive study information coded included the study citation (authors, year); study publication status (published, unpublished; κ = 1.00); and, if a published study, in which journal. We also coded the time frame of assessment of personality disorders and interpersonal functioning constructs (concurrent, functioning in the past 1 year; κ = 1.00) to ensure that they were within close temporal proximity; if a study reported prospective, longitudinal assessment, we included only effect sizes for the earliest available concurrent assessment because this yielded the largest sample size.

Sample characteristics

Descriptive sample information coded included participant age, coded as child/adolescent (younger than 18 years) or adult (18 years and older; κ = 1.00); participant sex, coded as predominantly (greater than 50%) male or female (κ = .94); and the sample population, coded as nonclinical (university student, community, school) or clinical (psychiatric inpatient or outpatient, forensic; κ = .79); where relevant, the comparison group was also coded as nonclinical (university student, community, school) or clinical (psychiatric inpatient or outpatient, forensic), but studies with comparison groups were infrequent enough to preclude examination in moderator analyses.

Effect size data

Information for the calculation of effect sizes coded included statistics for the association between personality disorder and interpersonal functioning variables (correlation coefficients, means and standard deviations, percentages, chi-square statistic, t statistic; ICC = .99) and the sample size(s) for each test (ICC = .99).

Data Analysis

Effect sizes for associations between personality disorders and interpersonal functioning were derived from each study. All effect sizes were either coded directly from studies as rs or were converted to rs prior to analyses using standard formulae (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001; Schmidt & Hunter, 2014). All effect sizes were coded so that positive effect sizes indicated larger associations with interpersonal dysfunction. Several studies reported multiple effect sizes for an interpersonal functioning domain (e.g., satisfaction and intimacy in the romantic domain); in such instances, effect sizes were averaged within studies, resulting in one effect size for each personality disorder and each interpersonal domain per study. Several studies also reported separate effect sizes for different assessment methods (e.g., self-report and informant report) or subsamples (e.g., males and females); in such instances, effect sizes were averaged across method or sample characteristic for overall analyses, but were examined separately in subsequent moderator analyses, as appropriate.

We conducted 120 separate meta-analyses of associations between each of the 10 personality disorders and the 12 interpersonal functioning domains. We used a random-effects model, which takes into consideration sample variation, as well as true between-study variation. Meta-analyses followed Hunter-Schmidt procedures (Schmidt & Hunter, 2014; see also Hunter & Schmidt, 2004). Like other meta-analytic approaches (e.g., Hedges & Olkin, 1985; Rosenthal, 1991), the Hunter-Schmidt approach accounts for random and systematic variation in study effects; the distinctive feature of this approach is that it also provides procedures to correct for measurement artifacts, namely measurement unreliability and restriction of range (though correction for the former is more common, given the information typically reported in studies). The Hunter-Schmidt approach has been compared with other meta-analytic procedures using simulation methods and has been found to yield generally comparable results, or even more accurate results under certain conditions (e.g., when population effect sizes are variable; Field, 2001, 2005; Schulze, 2004). We selected the Hunter-Schmidt approach because it allowed us to correct for both sampling error and measurement unreliability in study effects. Because personality disorder and interpersonal functioning constructs are indexed by ratings or scores on diagnostic interviews, questionnaires, or observed behavior, some amount of unreliability in the measures used is expected, thus leading to attenuated estimates of the true correlation between constructs (Campbell & Fiske, 1959). Reliability statistics (e.g., alpha coefficients) for the personality disorder and interpersonal functioning measures used were often, but not always, reported in the studies included in the meta-analysis—the Hunter-Schmidt approach uses the distribution of all available reliability estimates to correct for attenuation due to measurement unreliability, thereby allowing us to correct all effects for measurement unreliability, even those from studies that did not report reliability statistics.

Each meta-analysis yielded an estimated mean population effect size, corrected for sampling error and measurement unreliability, around which we calculated 80% credibility intervals and 95% confidence intervals (see Schmidt & Hunter, 2014). Credibility intervals and confidence intervals give different but complementary information. Credibility intervals define the range within which population effect sizes are distributed, and are calculated using the standard deviation; an 80% credibility interval that does not include zero indicates that more than 80% of the study effect sizes are greater than zero. Confidence intervals give an estimate of variability around the mean population effect size, and are calculated using the standard error; a 95% confidence interval that does not include zero indicates that the estimated mean population effect size is greater than 2 standard deviations away from zero and can be considered statistically significant. When neither the 80% credibility interval nor the 95% confidence interval for a mean population effect size included zero, we considered it to be a meaningful effect. We further considered effect sizes for a personality disorder-interpersonal functioning domain that fell outside both the 80% credibility interval and the 95% confidence interval for another personality disorder-interpersonal functioning domain to be meaningfully different from one another (see Schmidt & Hunter, 2014)—this allowed us to directly compare effect sizes across personality disorders and interpersonal functioning domains. Following conventional guidelines, we considered mean population effect sizes greater than |.20| to be modest, greater than |.30| to be moderate, and greater than |.50| to be large (Cohen, 1988).

In addition to computing mean effect sizes for associations between personality disorders and interpersonal style, we also applied the structural summary method developed for interpersonal circumplex profiles (see Gurtman, 1992; Gurtman & Pincus, 2003; Wright et al., 2009; Zimmermann & Wright, 2017). This approach yields three structural parameters, elevation (the average correlation with interpersonal style), amplitude (difference between the average correlation and the peak correlation of the profile), and angular displacement (the angular distance from 0° to the peak correlation of the profile), that summarize the structure of the entire profile of associations for each personality disorder, along with a goodness-of-fit statistic for the profile (see Gurtman, 1992; Gurtman & Pincus, 2003; Wright et al., 2009; Zimmermann & Wright, 2017, for detailed formulae used to compute these statistics).

To determine whether moderator analyses were warranted, we examined variability in the estimated mean population effect sizes (see Schmidt & Hunter, 2014). When the proportion of variance in observed effect sizes due to sampling error and measurement unreliability was greater than 75%, the population of studies was considered to be homogenous, suggesting a lack of study moderators; when the proportion was less than 75%, the population of studies was considered to be heterogeneous, and we thus examined potential moderators to account for this heterogeneity. Moderator analyses involved stratifying effect sizes by each moderator in turn, then conducting separate meta-analyses within each stratum; if the resulting mean effect sizes within each stratum fell outside both the 80% credibility interval and the 95% confidence interval for the comparison stratum, we concluded that the effect sizes come from different populations. All analyses were conducted using the Hunter & Schmidt Meta-Analysis Programs Package (version 1.2; Schmidt & Le, 2014).

Finally, we attempted to combat potential publication bias by including both published and unpublished studies, and by seeking out relevant unpublished data sets. We investigated potential publication bias attributable to the underrepresentation of published studies with small samples and the consequent lower power to detect significant effects by conducting cumulative meta-analyses for published studies based on sample size (see Kepes, Banks, McDaniel, & Whetzel, 2012; Kepes, Banks, & Oh, 2014; Schmidt & Hunter, 2014). In cumulative meta-analyses, studies are iteratively added to the overall meta-analysis based on decreasing sample sizes; increasing mean effect sizes indicates the possibility of publication bias in that studies with smaller samples that are published will tend to report larger effects (relative to studies with smaller samples that go unpublished, which will tend to report smaller effects).

Results

Overview of Studies Included in the Meta-Analyses

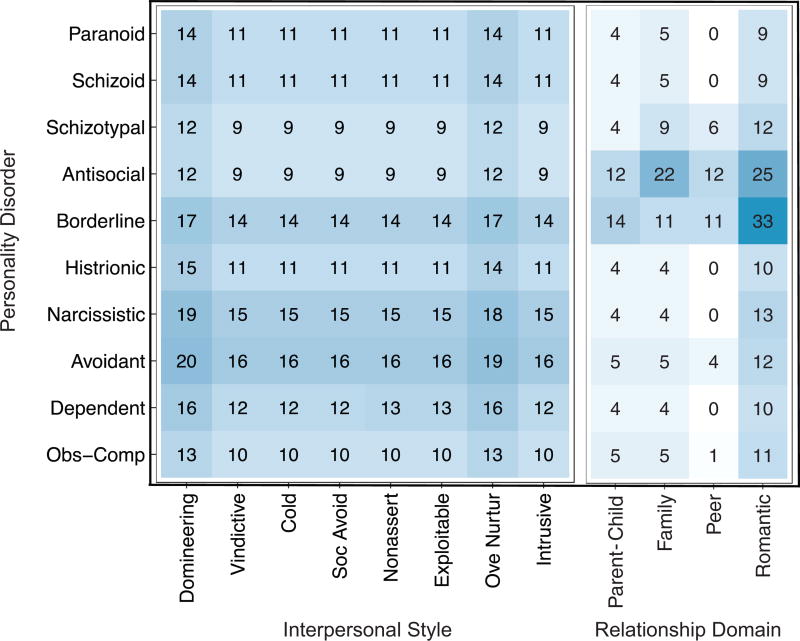

A total of 127 studies, comprising a total of 2,579 effect sizes, were included in this review (see Appendixes A and B for an overview of the included studies). The number of studies available for each meta-analysis varied widely. A heatmap of the number of studies in each meta-analysis is presented in Figure 4, with darker shading indicating a larger number of studies. The majority of studies examining associations between personality disorders and interpersonal functioning focused on interpersonal style (mean k = 13, SD = 3; mean N = 3,751, SD = 1,120) relative to functioning in specific relationship domains (mean k = 8, SD = 7; mean N = 2,531, SD = 2,961). Moreover, the majority of studies examining associations between personality disorders and interpersonal style focused on avoidant (mean k = 17, SD = 2; mean N = 4,694, SD = 442), narcissistic (mean k = 16, SD = 2; mean N = 6,296, SD = 442), and borderline (mean k = 15, SD = 1; mean N = 3,808, SD = 418) personality disorders; relatively fewer studies focused on the other personality disorders (mean ks ranged from 10 to 13, mean Ns ranged from 2,844 to 4,334). The majority of studies examining associations between personality disorders and functioning in specific relationship domains focused on antisocial (mean k = 18, SD = 7; mean N = 6,788, SD = 2,953) and borderline (mean k = 17, SD = 11; mean N = 5,414, SD = 5,313) personality disorders; considerably fewer studies focused on the other personality disorders (mean ks ranged from 5 to 8, mean Ns ranged from 1,153 to 3,836). Moreover, the majority of these studies focused on the romantic domain (mean k = 14, SD = 8; mean N = 4,796, SD = 3,285). The largest number of studies identified were for associations between borderline and antisocial personality disorders and functioning in the romantic domain (k = 33, N = 13,290 and k = 25, N = 7,379, respectively); there were considerably fewer studies that focused on the parent– child, family, or peer relationships (mean ks ranged from 3 to 7, mean Ns ranged from 852 to 2,318). In fact, there were studies of the peer relationship for only 5 of the 10 personality disorders.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of number of studies (k) in each meta-analysis of associations between personality disorders and interpersonal functioning. Obs-Comp = obsessive-compulsive. Soc Avoid = Socially Avoidant. Nonassert = Nonassertive. Ove Nurtur = Overly Nurturant. The k for each meta-analysis is given in each cell of the heatmap, with darker shading indicating a larger number of studies. See the online article for the color version of this figure.

Associations Between Personality Disorders and Interpersonal Style

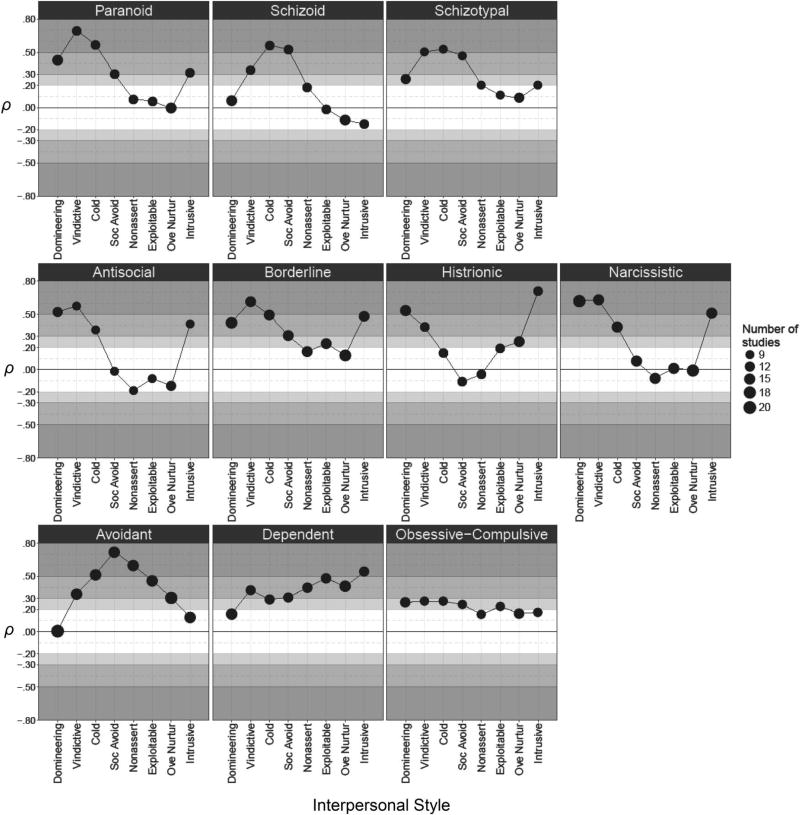

Average effect sizes, corrected for sampling error and measurement unreliability, are presented in Table 3 and illustrated in Figure 5. Each personality disorder showed a distinct pattern of associations with interpersonal style that was consistent with its characteristic form of dysfunction, as defined by its diagnostic criteria in DSM–IV and DSM–5 Section II. Comparisons of associations with interpersonal style for each personality disorder (i.e., whether the effect for one personality disorder-interpersonal functioning domain fell outside of the 80% credibility interval and 95% confidence interval of another personality disorder-interpersonal functioning domain) identified a number of meaningful differences in associations across personality disorders, indicating that each personality disorder (with two exceptions, noted below) showed unique associations with interpersonal dysfunction relative to the other personality disorders. Moreover, parameters derived using the structural summary method (see Table 4) revealed interpersonal differentiation and discriminability across the personality disorders. Taken together, the results for interpersonal style lend support for the construct and discriminant validity of the current personality disorder diagnoses, as well as the proposed conceptualization of disturbed self and interpersonal functioning.

Table 3.

Summary of Meta-Analytic Results for Associations Between Personality Disorders and Interpersonal Style

| Personality disorder-interpersonal style | k | N | r | ρ | 80% CrI | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paranoid | ||||||

| Domineering | 14 | 3,996 | .31 | .44 | .03, .86 | .27, .62 |

| Vindictive | 11 | 3,093 | .51 | .72 | .50, .94 | .60, .84 |

| Cold | 11 | 3,093 | .42 | .59 | .48, .70 | .51, .66 |

| Socially Avoidant | 11 | 3,093 | .22 | .31 | .18, .45 | .23, .39 |

| Nonassertive | 11 | 3,094 | .06 | .08 | −.00, .16 | .02, .14 |

| Exploitable | 11 | 3,092 | .04 | .06 | −.12, .24 | −.04, .16 |

| Overly Nurturant | 14 | 3,998 | .00 | −.01 | −.26, .25 | −.12, .11 |

| Intrusive | 11 | 3,094 | .23 | .33 | .04, .62 | .19, .47 |

| Schizoid | ||||||

| Domineering | 14 | 3,776 | .05 | .06 | −.34, .46 | −.11, .23 |

| Vindictive | 11 | 2,873 | .25 | .34 | .03, .64 | .19, .48 |

| Cold | 11 | 2,873 | .42 | .56 | .22, .89 | .39, .72 |

| Socially Avoidant | 11 | 2,873 | .39 | .52 | .21, .83 | .36, .67 |

| Nonassertive | 11 | 2,874 | .14 | .18 | −.02, .35 | .09, .27 |

| Exploitable | 11 | 2,872 | −.01 | −.01 | −.17, .15 | −.10, .07 |

| Overly Nurturant | 14 | 3,777 | −.08 | −.11 | −.35, .12 | −.22, −.01 |

| Intrusive | 11 | 2,874 | −.11 | −.14 | −.29, .00 | −.23, −.06 |

| Schizotypal | ||||||

| Domineering | 12 | 3,523 | .20 | .27 | .11, .65 | .09, .44 |

| Vindictive | 9 | 2,620 | .39 | .52 | .23, .82 | .36, .68 |

| Cold | 9 | 2,620 | .42 | .55 | .20, .90 | .36, .74 |

| Socially Avoidant | 9 | 2,620 | .38 | .49 | .23, .75 | .35, .63 |

| Nonassertive | 9 | 2,622 | .17 | .21 | .11, .32 | .14, .29 |

| Exploitable | 9 | 2,619 | .09 | .12 | −.02, .26 | .03, .20 |

| Overly Nurturant | 12 | 3,525 | .07 | .09 | −.07, .25 | .01, .17 |

| Intrusive | 9 | 2,621 | .16 | .21 | .09, .33 | .13, .29 |

| Antisocial | ||||||

| Domineering | 12 | 3,521 | .41 | .55 | .25, .85 | .41, .69 |

| Vindictive | 9 | 2,618 | .45 | .61 | .38, .84 | .48, .74 |

| Cold | 9 | 2,618 | .29 | .38 | .25, .51 | .30, .46 |

| Socially Avoidant | 9 | 2,618 | −.01 | −.01 | −.18, .15 | −.11, .08 |

| Nonassertive | 9 | 2,619 | −.15 | −.20 | −.44, .04 | −.33, −.07 |

| Exploitable | 9 | 2,617 | −.06 | −.08 | −.28, .11 | −.20, .03 |

| Overly Nurturant | 12 | 3,522 | −.11 | −.15 | −.38, .08 | −.26, −.04 |

| Intrusive | 9 | 2,619 | .32 | .44 | .03, .85 | .23, .66 |

| Borderline | ||||||

| Domineering | 17 | 4,486 | .33 | .45 | .04, .85 | .29, .60 |

| Vindictive | 14 | 3,582 | .48 | .64 | .42, .87 | .54, .75 |

| Cold | 14 | 3,582 | .39 | .52 | .34, .70 | .43, .60 |

| Socially Avoidant | 14 | 3,582 | .25 | .32 | .10, .54 | .22, .42 |

| Nonassertive | 14 | 3,583 | .13 | .17 | −.05, .39 | .07, .27 |

| Exploitable | 14 | 3,581 | .19 | .25 | .01, .49 | .14, .36 |

| Overly Nurturant | 17 | 4,487 | .10 | .14 | −.17, .45 | .02, .26 |

| Intrusive | 14 | 3,583 | .37 | .50 | .22, .78 | .38, .63 |

| Histrionic | ||||||

| Domineering | 15 | 4,092 | .37 | .54 | .24, .85 | .41, .67 |

| Vindictive | 11 | 3,093 | .27 | .39 | .02, .76 | .21, .57 |

| Cold | 11 | 3,093 | .11 | .15 | −.17, .48 | .00, .31 |

| Socially Avoidant | 11 | 3,093 | −.08 | −.11 | −.33, .11 | −.23, .00 |

| Nonassertive | 11 | 3,094 | −.03 | −.04 | −.25, .17 | −.15, .07 |

| Exploitable | 11 | 3,092 | .14 | .20 | .04, .35 | .11, .29 |

| Overly Nurturant | 14 | 3,998 | .18 | .26 | .04, .47 | .16, .35 |

| Intrusive | 11 | 3,094 | .49 | .72 | .38, .99 | .55, .88 |

| Narcissistic | ||||||

| Domineering | 19 | 7,057 | .45 | .62 | .33, .90 | .51, .73 |

| Vindictive | 15 | 6,058 | .46 | .63 | .35, .91 | .51, .75 |

| Cold | 15 | 6,058 | .28 | .38 | .18, .59 | .30, .47 |

| Socially Avoidant | 15 | 6,058 | .06 | .08 | −.10, .25 | .00, .16 |

| Nonassertive | 15 | 6,059 | −.05 | −.07 | −.30, .15 | −.17, .02 |

| Exploitable | 15 | 6,057 | .01 | .02 | −.12, .16 | −.05, .08 |

| Overly Nurturant | 18 | 6,963 | .00 | −.01 | −.21, .20 | −.09, .07 |

| Intrusive | 15 | 6,059 | .37 | .51 | .26, .77 | .40, .62 |

| Avoidant | ||||||

| Domineering | 20 | 5,455 | .01 | .01 | −.38, .39 | −.13, .14 |

| Vindictive | 16 | 4,456 | .26 | .34 | .15, .54 | .26, .43 |

| Cold | 16 | 4,456 | .40 | .52 | .39, .65 | .46, .59 |

| Socially Avoidant | 16 | 4,456 | .57 | .73 | .56, .89 | .65, .81 |

| Nonassertive | 16 | 4,457 | .47 | .60 | .45, .75 | .53, .67 |

| Exploitable | 16 | 4,455 | .36 | .46 | .32, .61 | .40, .53 |

| Overly Nurturant | 19 | 5,361 | .24 | .31 | .02, .64 | .19, .43 |

| Intrusive | 16 | 4,456 | .10 | .13 | −.03, .29 | .05, .20 |

| Dependent | ||||||

| Domineering | 16 | 5,063 | .12 | .16 | −.24, .57 | .00, .32 |

| Vindictive | 12 | 4,064 | .28 | .38 | .22, .54 | .29, .46 |

| Cold | 12 | 4,064 | .22 | .29 | .24, .35 | .24, .34 |

| Socially Avoidant | 12 | 4,064 | .23 | .31 | .15, .48 | .23, .40 |

| Nonassertive | 13 | 4,151 | .30 | .40 | .29, .52 | .34, .47 |

| Exploitable | 13 | 4,148 | .36 | .49 | .49, .49 | .45, .53 |

| Overly Nurturant | 16 | 5,054 | .30 | .41 | .26, .57 | .34, .49 |

| Intrusive | 12 | 4,065 | .39 | .55 | .33, .77 | .44, .66 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive | ||||||

| Domineering | 13 | 3,623 | .19 | .28 | .11, .67 | .11, .45 |

| Vindictive | 10 | 2,720 | .19 | .29 | .07, .64 | .11, .47 |

| Cold | 10 | 2,720 | .20 | .29 | .00, .57 | .14, .44 |

| Socially Avoidant | 10 | 2,720 | .18 | .26 | .14, .38 | .18, .34 |

| Nonassertive | 10 | 2,721 | .11 | .16 | −.09, .24 | .10, .23 |

| Exploitable | 10 | 2,719 | .16 | .24 | −.04, .44 | .13, .35 |

| Overly Nurturant | 13 | 3,625 | .12 | .17 | −.02, .36 | .08, .27 |

| Intrusive | 10 | 2,721 | .12 | .18 | −.01, .37 | .07, .29 |

Note. k = number of studies; N = total sample size; r = mean observed correlation; ρ = mean population effect size corrected for sampling error and measurement unreliability. ρs noted in bold indicate that the credibility and confidence intervals do not include zero.

Figure 5.

Results of meta-analyses (ρ = mean population effect sizes corrected for sampling error and measurement unreliability) examining associations between each personality disorder and interpersonal style. Soc Avoid = Socially Avoidant. Nonassert = Nonassertive. Ove Nurtur = Overly Nurturant. Shaded horizontal areas represent no effect (ρ = .00), or modest (ρ = |.20|), moderate (ρ = |.30|), and large (ρ = |.50|) effect sizes. The number of studies (k) for each meta-analysis is proportional to the area of its marker, with larger markers indicating a larger number of studies.

Table 4.

Structural Summary Statistics for Personality Disorders and Interpersonal Style

| Personality disorder | e | a | δ | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paranoid | .32 | .34 | 141.27° | .94 |

| Schizoid | .17 | .36 | 193.75° | .97 |

| Schizotypal | .31 | .24 | 171.31° | .94 |