Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate national trends and geographic variation in the availability of home health care from 2002–2015 and identify county-specific characteristics associated with home health care.

Design

Observational study

Setting

All counties in the United States

Participants

All Medicare-certified home health agencies included in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Home Health Compare system.

Measurements

County-specific availability of home health care, defined as the number of available home health agencies that provided services to a given county per 100,000 population aged ≥18 years.

Results

The study included 15,184 Medicare-certified home health agencies that served 97% of U.S. ZIP codes. Between 2002–2003 and 2014–2015, the county-specific number of available home health agencies per 100,000 population aged ≥18 years increased from 14.7 to 21.8 and the median (inter-quartile range) population that was serviced by at least one home health agency increased from 403,605 (890,329) to 455,488 (1,039,328). Considerable geographic variation in the availability of home health care was observed. The West, North-East, and South Atlantic regions had lower home health care availability than the Central regions, and this pattern persisted over the study period. Counties with higher median income, a larger senior population, higher rates of households without a car and low access to stores, more obesity, greater inactivity, and higher proportions of non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic populations were more likely to have higher availability of home health care.

Conclusion

The availability of home health care increased nationwide during the study period, but there was much geographic variation.

Keywords: Home health care, geographic variation, health services

INTRODUCTION

Post-acute care has become an important target for quality improvement and patient-centered care in the United States.1–5 Better post-acute care may benefit patients in multiple areas, including shorter hospital length of stay, reduction in inpatient cost, improvement in quality of life, better home-based primary care, and the prevention of unplanned readmissions.6–13 Home health agencies, which provide skilled nursing care, physical, occupational, and speech therapies, social work services, and assistance with activities of daily living to homebound patients,14 play an important role in the delivery of optimal post-acute care. Approximately 1.5 million Medicare patients, roughly 30% of hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries, were referred to home health care at discharge in 2012.15 In 2013, home health agencies served approximately 3.5 million beneficiaries with nearly 123 million visits, and Medicare paid almost $18 billion for these services.16 Home health care has been emphasized under the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act of 2014 to provide and improve care at individual patient and community levels.

The number of Medicare-certified home health agencies has increased over the last decade, from approximately 7,500 in 2000 to more than 12,000 in 2015, and the number of patients served increased from 2.5 million in 2000 to 3.5 million in 2013.17 Previous studies have shown that rural areas used home health care services less frequently and the Midwest and West regions were most likely to be served by only a single agency. However, many of these studies focused on specific communities, populations, or conditions and some of them do not reflect contemporary patterns.18–26 As home health care becomes a valuable component of the U.S. healthcare system, it is important to assess whether such services are available across the country and whether geographic patterns of the services have changed over the last decade. Identifying gaps in available home health care can inform future healthcare planning to enhance care of seniors.

Accordingly, we used 2002–2015 national home health care data, publicly available from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Home Health Compare (http://www.medicare.gov/download/downloaddb.asp), to assess temporal trends and geographic variation in the availability of home health care at the county level from 2002–2015. Using 2013–2015 data, we evaluated agency-specific and county-specific characteristics associated with the availability of home health care.

METHODS

Study Sample

Home health care data, at the individual agency level, include agency characteristics, ZIP codes served, and the corresponding time period. The Home Health Compare data were updated quarterly and represent approximately 12-month windows that span across two calendar years (e.g., June 1, 2002 through May 31, 2003 represents the 2002–2003 period). Data are currently available for 2002–2003 through 2014–2015.

Outcome

Our primary outcome was the availability of home health care, defined as the number of available agencies that provided services to a given county per 100,000 population aged ≥18 years. We assigned a home health agency to a county if it provided services to patients residing in any ZIP code within that county. An agency could be assigned to multiple ZIP codes, either within a county or across different counties, if it provided services within each of those ZIP codes. Similarly, one ZIP code could be linked to multiple agencies if patients in that ZIP code received services from more than one agency. For each ZIP code in a given county, we obtained U.S. Census data and aggregated the data to the county level to calculate the number of home health agencies per 100,000 population aged ≥18 years. We excluded counties or county equivalents if their total population was unavailable.

Characteristics of Home Health Agency and County

We included four home health agency characteristics in the analysis: 1) years of Medicare certification, 2) rates of full service (providing Medicare-required home health aide, nursing, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and social work by permanent staff versus by contract workers), 3) ownership (proprietary versus other), and 4) distance (miles) between the ZIP codes for an agency’s office and a patient’s home. County-specific characteristics included geographic, demographic, socioeconomic status, health risk factors, and lifestyle information (Supplementary Text S1). These county-specific characteristics are considered to be proxy measures for population-based health status13, 27–30 and may be associated with the availability and use of home health care.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted at the county level. We compared home health agency and county characteristics by tertiles of home health care availability. We assessed trends in availability at the county level by fitting a mixed model with a Poisson link function, county-specific random intercepts, and an ordinal time variable (time=0 for 2002–2003 and time=13 for 2014–2015). This modeled the number of home health agencies as a function of time, agency characteristics, and county-specific demographics, geographic characteristics, socioeconomic status, health risk factors, and lifestyle characteristics.

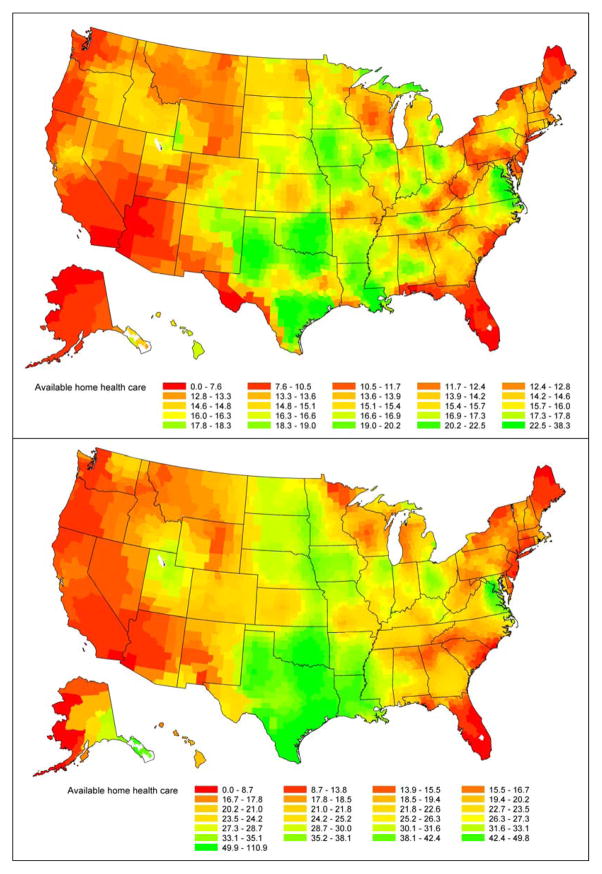

To assess geographic trends and variation in the availability of home health care, we mapped availability in 2002–2003 and 2014–2015, shading counties with a gradient from red (lowest availability) to green (highest availability). For each time period and geographic location, we quantified the variation in the availability of home health care over time by calculating the population-weighted quartile coefficient of dispersion. Decreases in the dispersion imply less heterogeneity in county-specific availability of home health care.

To evaluate agency-specific and county-specific characteristics associated with home health care, we restricted the study sample to the period from July 1, 2013 through September 30, 2015 and fitted the mixed model. We included state random intercepts in all models to account for within-state and between-state variations. Models accounted for spatial differences between counties, with the county-specific population aged ≥18 years used as an offset. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 64-bit (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Study Sample

The final study sample included 15,184 Medicare-certified home health agencies during the 14-year study period. These agencies were Medicare-certified for a median (inter-quartile-range [IQR]) of 15.9 (11.5) years, 71.1% were proprietary, and 80.5% had capacity to provide all six types of services by permanent staff. Collectively, these agencies served 39,773 ZIP codes, approximately 97% of all ZIP codes nationwide, across 3,228 counties or county equivalents. Table 1 shows observed county-level characteristics of home health agencies in 2014–2015 and Supplementary Table S1 includes additional characteristics across multiple time periods. County-specific characteristics varied by home health care availability. Compared to counties in the lowest tertile of availability, counties in the highest tertile had lower average median income ($46,000 vs. $52,000) and were less populated (30,000 vs. 600,000; Table 1). These observed patterns did not substantially change from 2002–2003 through 2014–2015 (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1.

County and home health agency characteristics by tertile of home health care availability in 2014–2015

| Characteristic, median (inter-quartile range) | Home Health Care Availability

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest tertile | Middle tertile | Highest tertile | |

| Distance between home health agency and patient home (mile) | 17.1 (10.1) | 25.6 (14.8) | 34.2 (15.1) |

| Home health agency’s years of Medicare certification | 16.9 (13.6) | 15.5 (13.3) | 14.3 (9.0) |

| Income ($10,000) | 5.2 (1.5) | 4.6 (1.6) | 4.6 (1.8) |

| Proportion Hispanic | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.2) |

| Proportion non-Hispanic black | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.1) | <0.1 (0.1) |

| Proportion non-Hispanic white | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.3) |

| Number of home health agencies per 100,000 population | 9.1 (9.5) | 36.6 (16.6) | 92.0 (48.8) |

| Total population (100,000) | 6.0 (11.5) | 0.9 (6.5) | 0.3 (0.7) |

Trends in Availability of Home Health Care

Between 2002–2003 and 2014–2015, the county-specific number of available home health agencies per 100,000 population aged ≥18 years increased from 14.7 to 21.8, the median (IQR) number of agencies providing services increased from 27 (35) to 38 (86), the median (IQR) number of ZIP codes served per agency decreased slightly from 33 (51) to 32 (48), and the median (IQR) distance between ZIP codes of an agency and a patient’s home increased from 17.4 (11.2) to 19.6 (13.1) miles. The county-specific median (IQR) population that was serviced by at least one agency increased from 403,605 (890,329) in 2002–2003 to 455,488 (1,039,328) in 2014–2015. The rate of ZIP codes lacking home health care decreased from 1.87% in 2002–2003 to 0.46% in 2014–2015. In adjusted analyses, for each time period, there was a relative increase of 2.84 (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.49 to 3.56) in the number of available home health agencies per 100,000 population aged ≥18 years, accounting for home health agency and county characteristics.

Geographic Variation in Home Health Care

There was considerable geographic variation in the availability of home health care over the study period (Figure 1, color maps are available online). Both the West and East regions had lower home health availability than the Central regions, and this pattern persisted between 2002–2003 and 2014–2015. Compared to the West-South Central division, all other divisions had significantly lower availability of home health care (Supplementary Figure S1). Although there was no change in the quartile coefficient of dispersion for availability nationwide (0.57 for 2002–2003 and 0.57 for 2014–2015), the coefficient increased from 0.53 to 0.64 for the Middle Atlantic, 0.25 to 0.34 for New England, and 0.38 to 0.52 for the Pacific, indicating increased heterogeneity in home health care in these regions over time (Supplementary Figure S1). The coefficient decreased in the East-North Central, West-North Central, and West-South Central divisions. There was significant positive spatial autocorrelation in the availability of home health care for every time period (p for Moran’s I <0.001), indicating availability is similar across adjacent counties.

Figure 1.

Geographic patterns in the number of available home health agencies per 100,000 population aged ≥18 years by U.S. county in 2002–2003 (top panel) and 2014–2015 (bottom panel). Availability was mapped by shading counties with a gradient from red to green (lowest rate in red to highest rate in green). To highlight the difference in geographic patterns between the periods of 2002–2003 and 2014–2015, each map has its own color scale. Color maps are available online.

Agency and County Characteristics Associated with Availability of Home Health Care

Counties with higher median income, a larger elderly population, higher rates of households without a car and low access to stores, more obesity, greater inactivity, and higher proportions of non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic populations were more likely to have higher availability of home health care. Counties with higher rates of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participants, a higher proportion of females, and more fast food restaurants were more likely to have lower availability of home health care (Table 2). All agency characteristics, except the proportion of full-service agencies, were significantly associated with the availability of home health care after adjusting for other county-specific characteristics. High-availability counties were more likely to be served by for-profit home health agencies, were more recently certified by Medicare, and necessitated driving further distances to reach patients (Table 2). On average, every $10,000 age-sex-race adjusted Medicare reimbursement paid to a home health agency was associated with an increase in the availability of home health agencies per 100,000 population by 0.59 percentage points (95% CI 0.43 to 0.77). Availability was lower for all counties located outside of the West-South Central division (Supplementary Figure S2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with availability of home health services

| Characteristics | Incidence Rate Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)* | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Home Health Agency | ||

| Home health agency’s years of Medicare certification | 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | <0.001 |

| Proportion proprietary | 1.45 (1.26–1.68) | <0.001 |

| Distance between home health agency and patient home (miles) | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | <0.001 |

| Proportion full service | 1.01 (0.88–1.17) | 0.861 |

| Geographic Division | ||

| South Atlantic | 0.41 (0.37–0.45) | <0.001 |

| Middle Atlantic | 0.28 (0.24–0.32) | <0.001 |

| New England | 0.33 (0.28–0.40) | <0.001 |

| East North Central | 0.59 (0.53–0.66) | <0.001 |

| East South Central | 0.53 (0.47–0.58) | <0.001 |

| West North Central | 0.66 (0.59–0.75) | <0.001 |

| Mountain | 0.42 (0.36–0.48) | <0.001 |

| Pacific | 0.28 (0.24–0.33) | <0.001 |

| Sociodemographic | ||

| Proportion female | 0.60 (0.54–0.67) | <0.001 |

| Proportion non-Hispanic white | 7.09 (4.35–11.55) | <0.001 |

| Proportion non-Hispanic black | 4.07 (2.42–6.86) | <0.001 |

| Proportion Hispanic | 4.61 (2.74–7.76) | <0.001 |

| Proportion aged ≥65 years | 1.97 (1.83–2.12) | <0.001 |

| Median income ($10,000) | 1.06 (1.03–1.10) | <0.001 |

| Proportion in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program | 0.57 (0.50–0.64) | <0.001 |

| Rate of households without car and low access to stores | 2.15 (1.86–2.48) | <0.001 |

| Rate of seniors with low income and low access to stores | 0.50 (0.22–1.17) | 0.110 |

| Health Risk Factors and Lifestyle | ||

| Age-adjusted adult obesity rate | 7.25 (3.05–17.24) | <0.001 |

| Number of recreation or fitness facilities per 1,000 population | 0.20 (0.13–0.30) | <0.001 |

| Number of fast food restaurants per 1,000 population | 0.71 (0.64–0.78) | <0.001 |

| Age-adjusted physically inactivity rate | 8.19 (3.61–18.57) | <0.001 |

| Medicare Reimbursement | ||

| Age-sex-race adjusted Medicare reimbursement per Medicare beneficiary in a given county ($1,000) | 1.59 (1.43–1.77) | <0.001 |

An incidence rate ratio less than 1 indicates that an increase in that county-specific characteristic is associated with a decrease in the availability of home health care. Similarly, an incidence rate ratio greater than 1 indicates that an increase in that county-specific characteristic is associated with an increase in the availability of home health care.

DISCUSSION

In this large, comprehensive investigation of the trends and geographic variation in the availability of home health care across the United States over the past 14 years, we found a nearly 3% per time period increase in the availability of home health care from 2002–2003 through 2014–2015. This was accompanied by a reduction in the number of ZIP codes lacking home heath care. Although availability of regional services does not necessarily equate to accessibility or utilization of services, we found that less than 0.5% of ZIP codes in the United States lacked home health care by 2014–2015. We also observed geographic variation in care, with West, Northeast, and South Atlantic divisions having lower home health availability when compared to the Central divisions. The provision of high-quality home-based care across all geographic areas will become an important component of the U.S. healthcare system in coming years given the increased proportion of patients discharged with post-acute care and home health care over the past decade31 and the projected growth in the number of U.S. seniors from 45 million in 2015 to 84 million in 2050.32 The persistent variation in the availability of home health care nationwide highlights opportunities to expand future services to improve care of the aging population.

Moreover, as the aging population grows, the market for in-home services is likely to increase, with such care providing a potentially more desirable and cost-effective option. It is conceivable that home health care may play an important role in palliative care in the future,33–36 as palliative care in the home setting is associated with better patient and caregiver satisfaction37–40 and decreased utilization of resources and costs.41

Our findings complement and extend those of previous studies.17–26 For example, Welch, Wennberg, and Welch used 1993 national claims history data and reported that the utilization of home health care tended to be highest in the South and lowest in the upper Midwest.25 Our findings demonstrate changing geographic patterns using more contemporary data. The South remains high in home health care availability, but the upper Midwest also shows high home health availability. Kenney and Dubay reported greater variation in home health care than skilled nursing stays, hospital stays, physician services, or hospital admissions.18 Our study illustrates that variation in home health care has persisted over time and it has increased in the Middle Atlantic, New England, and Pacific divisions.

The proportion female, median income, and urban/rural location of the county were all associated with availability of home health care in our study. Zhong et al. found that the accessibility of post-acute care was higher among women, patients residing in urban areas, and patients of higher socioeconomic status.42 Another study that examined 1.1 million discharges of Medicare patients aged ≥65 years found that patients who were referred to home health care at discharge were more likely to be older, female, live in an urban location, have lower income, have a longer length of stay, have higher illness severity scores, have a diagnosis of heart failure or sepsis, and be hospitalized in New England (versus the Pacific).15 Hartman et al. analyzed the 2002 Medicare home health care data and found that although the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries nationwide who lived in areas with few home health care agencies was relatively low, less than 1% of urban beneficiaries lived in ZIP codes with no or low use of home health care compared to more than 17% of the most rural beneficiaries.43 Unlike these previous studies that focused on the patient level, we focused on the county, an important and actionable perspective since improvement efforts require system changes beyond the reach of individual healthcare practitioners and patients.

We noted a number of additional variables associated with home health care availability in our study. Increased Medicare reimbursement for home health agencies per Medicare beneficiary resident in a given county was associated with increased availability of home health care; however, this finding does not provide information on quality of care or spending. An important focus of future research will be to link reimbursements with quality of care provided by home health agencies and conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis to compare cost and outcomes. We found that county-specific characteristics, such as lifestyle, were significantly associated with home health care use. Increases in obesity and physical inactivity were associated with increases in home health care use, and a greater number of recreation or fitness facilities was associated with a decrease in home health care use. These findings suggest that a lifestyle associated with poor health may increase the demand for home health care. Community-level interventions that focus on lifestyle may provide improved health and decrease the need for home health care. We found that there was no difference in availability of home health care between agencies providing all six types of services by their permanent staff and agencies using contractors to provide some of the services. This may reflect Medicare’s requirement that all home health agencies provide all of these services when needed, whether by way of employed or contract staff. Use of contract staff is common for smaller agencies and in less populous areas, particularly for speech and physical therapy because there are often fewer providers of these services in close proximity.

As with regional variability in health care as a whole, regional variation in home health care is complex and there is not a straightforward answer as to what drives it. Variation in temporal patterns may be the result of changes in the U.S. healthcare system, region-specific populations, socioeconomic status, lifestyle, healthcare market demand, or healthcare payment policy and spending. Future studies are warranted to elucidate how these factors affect geographic patterns. For example, improvements in home health care agencies, such as decreasing staff turnover, are important for reducing the geographic variation in home health care. Studies indicate that increased job satisfaction, prevention of job-related injuries, consistent patient assignment, reduced racial discrimination in the workplace, improvement in efficiency, care transition workflow from hospital to home health, an improved relationship with patients, and provision of health insurance are associated with lower intent to leave the job.44–48 The long distances between agencies and beneficiaries in our analyses likely indicate that staff are traveling long distances; such travel may contribute to staff turnover and be amenable to transportation and scheduling improvements.

Our study has several limitations. As we did not know how many patients from a given hospital were cared for by a specific home health agency after discharge, we were unable to weight home health agencies based on their actual levels of patient care. In an urban area, it is typical that a given home health agency might receive referrals from multiple hospitals and hospitals may assign the majority of their home health care referrals to certain agencies. We were unable to obtain information on such hospital-home health agency referral patterns. Some county-specific characteristics associated with the availability of home health care may reflect home health care utilization, rather than home health care availability. The possible drivers of home health care utilization could be multi-factorial, including county-specific business aspects, economic influences, social supports, and local practice culture; however, we were unable to address these factors in our analyses. Additionally, there has been substantial growth of large for-profit home health agencies since the 1980s, particularly in the South Central and Southeastern United States where there have been disproportionately more services rendered. Thus, the change in availability of home health care shown in our national maps may reflect industry growth in areas where market demand and culture for using home care were more favorable. Finally, our study was based on observational data that could be limited in the extent to which cause and effect can be inferred.

In conclusion, the availability of home health care has increased from 2002–2003 to 2014–2015 and ZIP codes lacking home health care has decreased to 0.5% in contemporary data. However, considerable geographic variation persisted; the West, Northeast, and South Atlantic regions had lower availability of home health care compared to the Central regions, even after adjusting for county-specific characteristics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest:

None

Author Contributions:

Dr. Wang had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept & design: YW, ECLL, and JHL

Acquisition of subjects and/or data: YW, YG

Analysis and interpretation of data: All authors

Preparation of manuscript: All authors

Sponsor’s Role: N/A

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Supplementary Text S1 Additional information on county-specific characteristics.

Supplementary Table S1 County and home health agency characteristics by tertile of home health care availability.

Supplementary Figure S1 Quartile coefficient of dispersion of home health care availability overall and by year and Census division. A decrease in the dispersion over time implies reduced heterogeneity in the county-specific number of home health care agencies per 100,000 population aged ≥18 years.

Supplementary Figure S2 Adjusted association between county geographic location and the number of available home health care agencies per 100,000 population aged ≥18 years. The West-South Central division was used as the referent group for geographic location.

References

- 1.Ackerly DC, Grabowski DC. Post-acute care reform–beyond the ACA. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:689–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mechanic R. Post-acute care — The next frontier for controlling Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:692–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller ME. [Accessed July 11, 2016];Medicare post-acute care reforms. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/congressional-testimony/20130614_wandm_testimony_pac.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed July 6, 2016]; Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/SNFPPS/post_acute_care_reform_plan.html.

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed April 19, 2016]; Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Post-Acute-Care-Quality-Initiatives/IMPACT-Act-of-2014-and-Cross-Setting-Measures.html.

- 6.Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome — An acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:100–102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1212324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joynt KE, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmissions—Truth and consequences. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(15):1366–1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1201598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joynt KE, Jha AK. A path forward on Medicare readmissions. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1300122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashton C, Wray N. A conceptual framework for the study of early readmission as an indicator of quality of care. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;43(11):1533–41. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berenson RA, Paulus RA, Kalman NS. Medicare’s readmissions-reduction program-A positive alternative. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(15):1364–1366. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1201268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Axon RN, Williams MV. Hospital readmission as an accountability measure. JAMA. 2011;305(5):504–505. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Pandolfi MM, Fine J, et al. Community level association between home health and nursing home performance on quality and hospital 30-day readmissions for Medicare patients. Home Health Care Management & Practice. 2016 Apr 7; doi: 10.1177/1084822316639032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed July 10, 2016]; Available at: http://www.medicare.gov/what-medicare-covers/home-health-care/home-health-care-what-is-it-what-to-expect.html.

- 15.Jones CD, Wald HL, Boxer RS, et al. Characteristics associated with home health care referrals at hospital discharge: results from the 2012 national inpatient sample. Health Services Research. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed July 02, 2016]; Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HomeHealthQualityInits/index.html?redirect=/HomeHealthQualityInits.

- 17.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC: MedPAC; [Accessed July 11, 2016]. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/reports/chapter-9-home-health-care-services-(march-2015-report).pdf?sfvrsn=0. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenney GM, Dubay LC. Explaining area variation in the use of Medicare home health-services. medical care. 1992;30(1):43–57. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199201000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.FitzGerald JD, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Changes in regional variation of Medicare home health care utilization and service mix for patients undergoing major orthopedic procedures in response to changes in reimbursement policy. Health Services Research. 2009;44(4):1232–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riggs JS, Madigan EA. Describing variation in home health care episodes for patients with heart failure. Home Health Care Management & Practice. 2012;24(3):146–52. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCall N, Komisar HL, Petersons A, et al. Medicare home health before and after the BBA. Health Affairs. 2001;20(3):189–98. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCall N, Korb J, Petersons A, et al. Constraining Medicare home health reimbursement: What are the outcomes? Health Care Financial Review. 2002;24(2):57–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCall N, Korb J, Petersons A, et al. Decreased home health use: Does it decrease satisfaction? Medical Care Research and Review. 2003b;61(1):64–88. doi: 10.1177/1077558703260183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCall N, Petersons A, Moore S, et al. Utilization of home health services before and after the Balanced Budget Act of 1997: What were the initial effects? Health Services Research. 2004;38(1 Pt 1):85–106. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welch HG, Wennberg DE, Welch WP. The use of Medicare home health care services. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(5):324–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608013350506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.South Carolina Rural Health Research Center. [Accessed July 11, 2016];Home Health Care Agency Availability in Rural Counties. Available at: http://rhr.sph.sc.edu/report/(11-2)HHC_Agency_2014.pdf.

- 27.Spatz ES, Beckman AL, Wang Y, et al. Geographic variation in trends and disparities in acute myocardial infarction hospitalization and mortality by income levels, 1999–2013. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(3):255–265. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrin J, St Andre J, Kenward K, et al. Community factors and hospital readmission rates. Health services research. 2015 Feb 1;50(1):20–39. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iyer M, Bhavsar GP, Bennett KJ, et al. Disparities in home health service providers among Medicare beneficiaries with stroke. Home health care services quarterly. 2016 Jan 2;35(1):25–38. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2016.1175991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson LE, Litaker DG. County-level poverty is equally associated with unmet health care needs in rural and urban settings. The Journal of Rural Health. 2010 Sep 1;26(4):373–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krumholz HM, Nuti SV, Downing NS, et al. Mortality, hospitalizations, and expenditures for the Medicare population aged 65 years or older, 1999–2013. JAMA. 2015;314(4):355–365. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: The older population in the United States. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau. 2014;24:25–1140. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rome RB, Luminais HH, Bourgeois DA, et al. The role of palliative care at the end of life. The Ochsner Journal. 2011;11(4):348–352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schenker Y, Arnold R. The next era of palliative care. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1565–1566. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.11217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrison R Sean, Meier Diane E. Palliative care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(25):2582–2590. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp035232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arnold RM, Zeidel ML. Dialysis in frail elders—A role for palliative care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(16):1597–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0907698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riolfi M, Buja A, Zanardo C, et al. Effectiveness of palliative home-care services in reducing hospital admissions and determinants of hospitalization for terminally Ill patients followed up by a palliative home-care team: A retrospective cohort study. Palliative medicine. 2013 Dec 23; doi: 10.1177/0269216313517283. 0269216313517283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alturki Abdulrahman. Patterns of care at end of life for people with primary intracranial tumors: Lessons learned. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2014;117(1):103–115. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pace A, Di Lorenzo C, Capon A, et al. Quality of care and rehospitalization rate in the last stage of disease in brain tumor patients assisted at home: a cost effectiveness study. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:225–227. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: Results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55(7):993–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen CY, Thorsteinsdottir B, Cha SS, et al. Health care outcomes and advance care planning in older adults who receive home-based palliative care: a pilot cohort study. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2015;18(1):38–44. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhong L, Mahmoudi E, Giladi AM, et al. Utilization of post-acute care following distal radius fracture among Medicare beneficiaries. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2015;40(12):2401–9. e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.08.026. Epub 2015 Oct 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hartman L, Jarosek SL, Virnig BA, Durham S. Medicare-certified home health care: urban-rural differences in utilization. The Journal of Rural Health. 2007 Jun 1;23(3):254–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2007.00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stone R, Wilhelm J, Bishop CE, et al. Predictors of intent to leave the job among home health workers: Analysis of the national home health aide survey. The Gerontologist. 2016 doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee D, Muslin I, McInerney M. Perceived racial discrimination among home health aides: evidence from a national survey. Journal of Health & Human Services Administration. 2016;38(4):414–437. 24p. 2 Charts. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valdman VG, Rosko MD, Mukamel DB. Assessing overall, technical, and scale efficiency among home health care Agencies. Health Care Management Science. 2016:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10729-015-9351-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nasarwanji M, Werner NE, Carl K, et al. Identifying challenges associated with the care transition workflow from hospital to skilled home health care: perspectives of home health care agency providers. Home Health Care Services Quarterly. 2015;34(3–4) doi: 10.1080/01621424.2015.1092908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sneltvedt T, Bondas T. Proud to be a nurse? Recently graduated nurses’ experiences in municipal health care settings. Scand J Caring Sci. 2015 Oct 13; doi: 10.1111/scs.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.