Abstract

AIM

To investigated clinical, endoscopic and histopathological parameters of the patients presenting with ileocecal ulcers on colonoscopy.

METHODS

Consecutive symptomatic patients undergoing colonoscopy, and diagnosed to have ulcerations in the ileocecal (I/C) region, were enrolled. Biopsy was obtained and their clinical presentation and outcome were recorded.

RESULTS

Out of 1632 colonoscopies, 104 patients had ulcerations in the I/C region and were included in the study. Their median age was 44.5 years and 59% were males. The predominant presentation was lower GI bleed (55, 53%), pain abdomen ± diarrhea (36, 35%), fever (32, 31%), and diarrhea alone (9, 9%). On colonoscopy, terminal ileum was entered in 96 (92%) cases. The distribution of ulcers was as follows: Ileum alone 40% (38/96), cecum alone 33% (32/96), and both ileum plus cecum 27% (26/96). The ulcers were multiple in 98% and in 34% there were additional ulcers elsewhere in colon. Based on clinical presentation and investigations, the etiology of ulcers was classified into infective causes (43%) and non-infective causes (57%). Fourteen patients (13%) were diagnosed to have Crohn’s disease (CD).

CONCLUSION

Non-specific ileocecal ulcers are most common ulcers seen in ileo-cecal region. And if all infections are clubbed together then infection is the most common (> 40%) cause of ulcerations of the I/C region. Cecal involvement and fever are important clues to infective cause. On the contrary CD account for only 13% cases as a cause of ileo-cecalulcers. So all symptomatic patients with I/C ulcers on colonoscopy are not Crohn’s.

Keywords: Ileocecal, Crohn’s disease, Diffuse large B-cell non-hodgkin’s lymphoma

Core tip: This is one of the largest studies till date defining etiology, endoscopic and histological features of ileocecal (I/C) ulcers. Non-specific ileocecal ulcers are most common ulcers seen in ileo-cecal region. And if all infections are clubbed together then infection is the the most common (> 40%) cause of ulcerations of the IC region. On the contrary Crohn’s disease (CD) account for only 13% cases as a cause of ileo-cecal ulcers. So all symptomatic patients with I/C ulcers on colonoscopy are not CD. Also, we conclude that with increasing use of Colonoscope in diagnosis and treatment, majority of the patients with ileo-cecal ulcers can be managed conservatively without surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Term ileocecum pertains to the cecum and the terminal filament of ileum including the region where they are connected by the ileocecal (I/C) valve[1]. Due to distinct anatomy and physiology this region is affected by various diseases like ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease (CD), non-specific ulcers, Malignancies, Amoebiasis, Enteric fever and Tuberculosis (TB)[2-6]. CD in particular affect Ileum alone or ileo-colonic region in about 60%-70% cases[7]. But whether 60%-70% of I/C ulcers are CD needs evaluation. I/C ulcers may manifest as small bowel obstruction, abdominal pain, perforation, acute or chronic gastrointestinal blood loss, cachexia, fever or malabsorption syndrome[8]. There is paucity of data on etiology, clinical profile and histo-pathological correlation of patient with I/C ulcerations. To evaluate the etiology of ileocecal ulcers is challenging for Clinician, Endoscopist and Histopathologistalike[9-13]. In the present study, clinical, endoscopic and histopathological parameters of the patients presenting with ileocecal ulcers on colonoscopy, were summarized, and investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted at Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi. This was an observational study conducted over a period of 18 mo from May 2010 to October 2011.Colonoscopy was done with fibro-optic colonoscope (Olympus, Japan 180 cf or 160 cf). Colonic preparation was done using a polyethylene glycol-electrolyte-based solution (Peglec, Tablets India Ltd, Chennai). The procedure was performed under conscious sedation with intravenous diazepam (5-10 mg) and pentazocine (25-50 mg). During colonoscopy a careful search was made for the presence of ulcers in cecum,ileocecal valve or terminal ileum. If any ulcer was present then multiple biopsies were obtained from the lesion and the margins for histopathological examination. Exclusion criteria included patients < 18 years of age and asymptomatic patients undergoing screening colonoscopy. The data was prospectively collected. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent for the treatment and colonoscopy was obtained from all patients. We did not seek individual ethical approval by the Committee because this was an observational study without interpositions and with the medical practice necessary for therapeutic purposes. Descriptive statistics was used for data analysis. Continuous variables were presented as mean or median (range). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. SPSS 17 for windows statistics package (Microsoft corp. Richmond, VA) was used for analysis. One hundred and four patients with ileo-cecal ulcerations and biopsy specimen subjected to histopathological examination were included in the study.

Definitions

(1) Amoebic ulcers were diagnosed if the biopsy specimen demonstrated trophozoites of E. histolytica or test for amoebic serology was positive in blood sample; (2) enteric or typhoid ulcers were diagnosed either on histology or if widal titer was positive or blood culture was positive for Salmonella typhi; (3) unspecified infective ulcers were diagnosed if patient presented with acute onset diarrhea or dysentery with febrile illness and tests for other infections like amoebiasis; enteric fever were negative; or by histopathological evidence; (4) tubercular ulcers were diagnosed if tubercle bacilli was demonstrated in biopsy specimen or by presence of caseating granuloma in biopsy specimen or if there was evidence of extra-intestinal tuberculosis; or past history of tuberculosis; (5) Crohn’s ileocecal disease was diagnosed by presence of skip lesions, pseudopolyps or fistulas on endoscopic or radiological examination with presence of cryptitis or cryptic abscesses or non-caseating granulomas on biopsy. Use of data and criterias from past studies was made to differentiate between TB and CD[9-11,13]; (6) NSAID induced ileocecal ulcers were diagnosed either on histology or if patient had history of NSAID intake; (7) malignant ileocecal ulcers were diagnosed if malignancy was demonstrated on biopsy from ulcers or biopsy/fine needle aspiration cytology from surrounding lymphnode; (8) psedomembranous colitis was diagnosed if stool examination demonstrated the presence of C. difficle toxin A and B; (9) eosinophilic enteritis was diagnosed as per standard criteria[14]; (10) non-specific ileocecal ulcer was diagnosis of exclusion; where other causes were ruled out and biopsy demonstrated the same; (11) small ulcers were ulcers with maximum diameter < 1.5 cm; and (12) large ulcers were ulcers with maximum diameter of > 1.5 cm.

RESULTS

Total 1632 colonoscopies were performed during the study period. One hundred and four (7%) patients with ulcer in cecum, ileo-cecal valve or terminal ileum and biopsy specimen subjected for histopathological examination formed the study group. The median age was 44.5 years with a range of 18-85 years. Sixty-one (59%) patients were males. The predominant presentation was lower Gastro-intestinal (GI) bleed (n = 55), Pain abdomen with or without diarrhoea (n = 36), weight loss (n = 20), constipation (n = 10), diarrhoea alone (n = 9). Associated fever was present in 33 patients. On colonoscopy, terminal ileum could be entered in 96 (92%) cases. The distribution of ulcers was as follows: Ileum alone 38 (40%), cecum alone 32 (33%), and both ileum plus cecum 26 (27%). In the 8 patients in whom ileum could not be entered ulcerations were present on the cecum and the IC valve. The ulcers were multiple in 99 (98%). In 35 (34%) there were additional ulcers elsewhere in colon. One patient left the hospital against medical advice. Three patients expired. Eight patients required surgical treatment. Remaining 92 patients had uneventful recovery. Various causes of Ileo-cecal ulcers are summerised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Etiology of ileo-cecal ulcers n (%)

| Infective causes n = 45 (43%) | Amoebic | 13 (12) |

| Tubercular | 11 (11) | |

| Typhoid | 4 (4) | |

| Pseudomembranous colitis | 2 (2) | |

| Unspecified bacterial infections | 15 (14) | |

| Non-infectious causes n = 59 (57%) | CD | 14 (13) |

| NSAID induced | 6 (6) | |

| Malignant | 6 (6) | |

| Miscellaneous | 4 (4) | |

| Non-specific | 29 (28) |

CD: Crohn’s disease; NSAID: Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug.

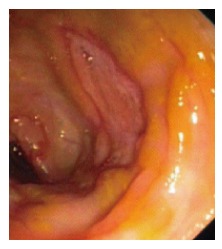

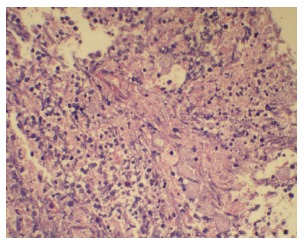

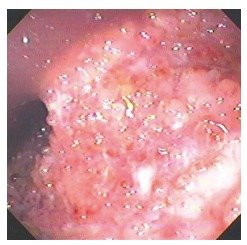

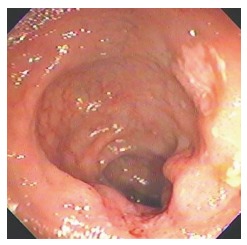

Amoebic ulcers (n = 13) predominantly affected males. Most common presentation was lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Twelve patients had multiple ulcers. Ileum was affected in only one case but cecum (Figure 1) was involved in twelve cases. Ulcers were large, multiple, necrotic, with inflammatory edges. Amoebic serology was positive in all patients. Amoebic trophozoites (Figure 2) were seen on biopsy in 1 patient. Six patients had active ooze from ulcers. Two patients required surgery in form of right hemicolectomy to control the bleed. Rest were managed with conservative treatment including antibiotics.

Figure 1.

Amoebic ulcer in cecum.

Figure 2.

Amoebic trophozoites on histopathology.

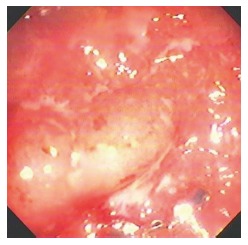

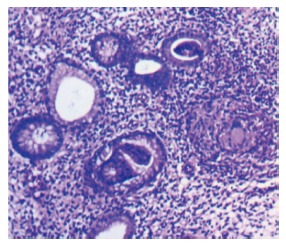

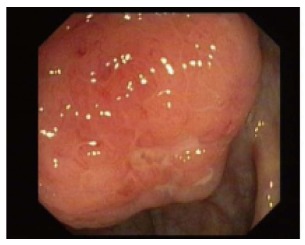

Eleven patients had I/C ulcers due to tuberculosis (Figure 3). Presenting complaints were weight loss and pain abdomen. Cecum was cicatrised in 8 patients and I/C valve was deformed in four. Ulcers were small and multiple. Biopsy (Figure 4) was diagnostic in 7. In view of persistant obstruction 1 patient required surgery while the remaining 10 patients were managed with anti-tubercular treatment.

Figure 3.

Tubercular ulcers in ileum.

Figure 4.

Tubercular granuloma.

Fifteen patients were diagnosed as unspecified infective ulcers. GI bleed and fever were most common presentation. Ileum was involved in 10 and cecum in 8 patients. Ulcers were small, large, multiple and with various morphologies. Ten patients had active ooze or stigmata of recent bleed,on colonoscopy. Biopsy was diagnostic in 9 patients. One patient expired due to sepsis and renal failure. One patient left the hospital against medical advice.

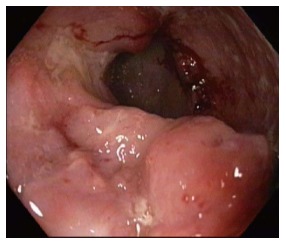

Fourteen patients were diagnosed as ileocecal Crohn’s. Eleven were females. Most common presenting complaints were pain abdomen or gastrointestinal bleed. Ileum was involved in 12, ceacum in 6 and I/C valve in only one. Ulcers were small or large. Skip lesion were present in 3 cases. Pseudopolyps (Figure 5) were present in two cases. Biopsy was diagnostic in 6 patients. No patient required surgical intervention.

Figure 5.

Pseudopolyps in Crohn’s disease.

Six patients had non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) induced I/C ulcers. All had history of NSAID intake ranging for 5 d to 24 mo prior to presentation. Presenting complaints were gastrointestinal bleed, diarrhea, pain abdomen. No patient had fever. Ileum was involved in 5 patients and cecum in 3. Biopsy was diagnostic in 1 patient. All patients recovered without the need for surgery.

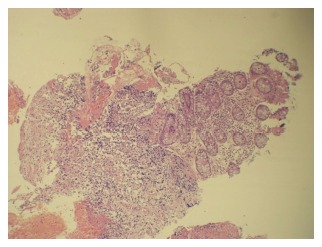

Six patients were diagnosed to have malignancies-3 adenocarcinoma cecum and 3 ileocecal diffuse large B-cell non-hodgkin’s lymphoma (DLBCL) (Figures 6 and 7). Colonic biopsy (Figure 8) was diagnostic in 4 cases. Two patients of adenocarcinoma were operated, while 1 was treated with chemotherapy. The later expired. Of the 3 DLBCLall were treated with chemotherapy.

Figure 6.

Ulcer on ileo-cecal valve ileocecal-lymphoma.

Figure 7.

Ileal ulcer-lymphoma.

Figure 8.

Biopsy demonstrating lymphoma.

Four patients had I/C ulcers secondary to enteric fever. Presenting complaints were fever, pain abdomen, GI bleed. Ileum was involved in 3 cases and cecum in 2 cases. Ulcers were large (> 1.5 cm) with necrotic slough; associated with active ooze in 2 cases. Biopsy was diagnostic in one.Haemostasis by endoscopic therapy was achieved in one patient while one patient underwent right hemicolectomy.

Two patients were diagnosed with eosinophilic enteritis with ileal ulcers on colonoscopy. Both presented with pain abdomen.

Two patients were diagnosed as pseudomembranous colitis with I/C involvement. Biopsy was diagnostic in one patient whereas stool for Clostridium difficle toxin A and B was positive for both. On endoscopy Ulcers were multiple with necrotic slough.

Twenty-nine patients were diagnosed with non-specificileocecalulcers (Figure 9). Presenting complaints were GI bleed in 14, pain abdomen in 11 and diarrhea in 7 patients. No patient had fever. Ileum was involved in 21 patients. Ulcers were small or large and with various morphologies. Active ooze was noted in eight patients of whom six were managed by Endoscopic therapy. Two required surgery. One expired due to massive bleeding.

Figure 9.

Non-specific ileal ulcer.

With infective cause, fever was significantly more common (47% vs 19%, P < 0.01) and cecum was preferentially involved (82% vs 45%, P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

This is one of the largest study till date defining etiology,colonoscopic and histo-pathological features of ileo-cecal ulcers.This study is interesting for several reasons.

First, Crohn’s disease in particular affect ileum or ileum along with colon in about 60%-70% patients[7]. However, the converse is not true, i.e., 80% of ileo-cecal ulcers are not Crohn’s. In our study CD was cause for ileo-cecal ulcers in 13% of patients.Ileum was affected in 90% cases. Pain abdomen and GI bleed were common presentations. Absence of fever and sparing of ileo-cecal valve were helpful in diagnosing Crohn’s.

Second, in our study most common etiology of ileo-ceal ulcers was non- specific ulcers. Clinically these ulcers manifest without fever. They are pleomorphic in nature on colonoscopy and predominantly involve the ileum. They can cause massive GI bleed and result in mortality. However, if treated promptly hemostasis can be achieved by endoscopic treatment. These results were comparable to studies by Boydstun et al[6] and Thomas et al[15] in terms of, presenting complaints and site of ulcers. However, as they conducted studies when endoscopic methods of hemostasis were not practiced. So surgery was the only curative treatment for their patients.

Third, Infections,if clubbed together, was most common cause of ulcerations in Ileo-cecal region. Findings were comparable with a Chinese study[8]. Both these studies demonstrated that most common cause of ileocecal ulcers is infection especially in tropics. We also hypothesize that infection can be most common etiology of ulcers in other parts of world. Though, Amoeba and Tuberculosis are uncommon in Europe and America, bacterial infections are common worldwide.

Amoebic serology was useful diagnostic tool to differentiate amoebic ileocecal ulcers from other causes of ileocecal ulcers. Male sex, fever, gastrointestinal bleed, and large necrotic ulcers involving the cecum with ileal sparing favored amoebic ulcers. Findings were comparable to other studies[16].

Multiple ulcers with cicatrisation of Cecum and deformed I/C valve suggest tubercular etiology. Biopsy is always not diagnostic. Abdominal pain, weight loss, fever, and a lump in the abdomen are common presentations. Clinical features combined with colonoscopy need to be considered to start treatment. Cai et al[8] even suggested that based on these findings anti-tubercular treatment can be started and response to treatment can be evaluated after 6-8 wk of treatment.

In enteric fever, patients are febrile with widal test or blood culture positive for S. typhi. Large ieal ulcers with necrotic slough; associated with active ooze is common colonoscopic findings. Majority of them can be treated by conservative treatment including antibiotic therapy.

Unspecified bacterial infections was most common cause of infective ileocecal ulcers. Febrile patients with multiple ileal ulcers and associated oozing of blood are common findings. Tests for other infective causes are negative. These findings were comparable to other studies but in these studies causative bacteria were defined[17,18].

And lastly, NSAIDs, Eosinophilic enteritis and malignancies have been described in literature as cause of ulcerations in ileo-cecal region[3,14,19]. These causes were also noted in our study. But, they were cause of ulcerations in minor group of patients. Findings of our study were comparable with literature.

To conclude, non-specific ileocecal ulcers are most common ulcers seen in ileo-cecal region. And if all infections are clubbed together then infection is the the most common (> 40%) cause of ulcerations of the IC region. Cecal involvement and fever are important clues to infective cause. On the contrary CD account for only 13% cases as a cause of ileo-cecalulcers. So all symptomatic patients with I/C ulcers on colonoscopy are not Crohn’s. And with increasing use of Colonoscope in diagnosis and treatment, majority of the patients with ileo-cecal ulcers can be managed conservatively without need for surgery.

COMMENTS

Background

Evaluation of ileocecal ulcers is challenging for Clinician, Endoscopist and Histopathologist. Data on ileocecal ulcers, from Asian countries, differ from western world. In this study, all these parameters of the patients presenting with ileocecal ulcers on colonoscopy, were summarized, and investigated.

Research frontiers

Colonoscope is a novel tool that allows evaluation as well as treatment of ileocecal ulcers in majority of cases. It has largely replaced surgery for evaluation and treatment of these ulcers. The present study confirmed this hypothesis in Indian patients.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The present study showed that symptomatic ileo-cecal ulcers, are mainly caused by infections; specially in tropical Asian countries. Non-specific ulcers also predominate the list and are cause of significant morbidity and mortality. Fortunately, with the use of colonoscope for achieving hemostasis majority of these patients can be managed conservatively.

Applications

This study suggests that Crohn’s disease is cause of ulcers in ileo-cecal region in a very small subset of patients. Majority of ulcers are caused by infections. Involvement of cecum and fever are important clues to diagnoses these infective ulcers.

Terminology

Ileo-cecal (I/C) ulcers are ulcers located in terminal ileum, cecum or on ileocecal valve noted during colonoscopic examination.

Peer-review

I/C ulcers were evaluated in this study. Jay Toshniwal et al evaluated their patients undergoing colonoscopy. It was detected that 104 patients (of 1632 colonoscopies) had ulcerations in the I/C region and non-specific ileocecal ulcers are most common ulcers seen in ileo-cecal region. The results may be meaningful for interested specialists.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent for the treatment and colonoscopy was obtained from all patients. We did not seek individual ethical approval by the Committee because this was an observational study without interpositions and with the medical practice necessary for therapeutic purposes.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent from the included patients was not obtained to participate in the study. However, each patient provided written informed consent for undergoing colonoscopy and treatment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: We have no financial relationships to disclose.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: February 4, 2017

First decision: March 22, 2017

Article in press: June 7, 2017

P- Reviewer: Imagawa A, Yazisiz V S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Barret KE. USA: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2006. Lange Gastrointestinal Physiology. 1st ed; p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvares JF, Devarbhavi H, Makhija P, Rao S, Kottoor R. Clinical, colonoscopic, and histological profile of colonic tuberculosis in a tertiary hospital. Endoscopy. 2005;37:351–356. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhai L, Zhao Y, Lin L, Tian Y, Chen X, Huang H, Lin T. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma involving the ileocecal region: a single-institution analysis of 46 cases in a Chinese population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:509–514. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318237126c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wanke C, Butler T, Islam M. Epidemiologic and clinical features of invasive amebiasis in Bangladesh: a case-control comparison with other diarrheal diseases and postmortem findings. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38:335–341. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JH, Kim JJ, Jung JH, Lee SY, Bae MH, Kim YH, Son HJ, Rhee PL, Rhee JC. Colonoscopic manifestations of typhoid fever with lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boydstun JS, Gaffey TA, Bartholomew LG. Clinicopathologic study of nonspecific ulcers of the small intestine. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:911–916. doi: 10.1007/BF01309496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santana GO, Souza LR, Azevedo M, Sá AC, Bastos CM, Lyra AC. Application of the Vienna classification for Crohn’s disease to a single center from Brazil. Arq Gastroenterol. 2008;45:64–68. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032008000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai J, Li F, Zhou W, Luo HS. Ileocecal ulcer in central China: case series. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:3169–3173. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9548-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makharia GK, Srivastava S, Das P, Goswami P, Singh U, Tripathi M, Deo V, Aggarwal A, Tiwari RP, Sreenivas V, et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histological differentiations between Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:642–651. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu H, Liu Y, Wang Y, Peng L, Li A, Zhang Y. Clinical, endoscopic and histological differentiations between Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis. Digestion. 2012;85:202–209. doi: 10.1159/000335431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pulimood AB, Amarapurkar DN, Ghoshal U, Phillip M, Pai CG, Reddy DN, Nagi B, Ramakrishna BS. Differentiation of Crohn’s disease from intestinal tuberculosis in India in 2010. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:433–443. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i4.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gan HT, Chen YQ, Ouyang Q, Bu H, Yang XY. Differentiation between intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease in endoscopic biopsy specimens by polymerase chain reaction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1446–1451. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pulimood AB, Peter S, Ramakrishna B, Chacko A, Jeyamani R, Jeyaseelan L, Kurian G. Segmental colonoscopic biopsies in the differentiation of ileocolic tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:688–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman HJ. Adult eosinophilic gastroenteritis and hypereosinophilic syndromes. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6771–6773. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas WE, Williamson RC. Nonspecific small bowel ulceration. Postgrad Med J. 1985;61:587–591. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.61.717.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagata N, Shimbo T, Akiyama J, Nakashima R, Nishimura S, Yada T, Watanabe K, Oka S, Uemura N. Risk factors for intestinal invasive amebiasis in Japan, 2003-2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:717–724. doi: 10.3201/eid1805.111275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shigeno T, Akamatsu T, Fujimori K, Nakatsuji Y, Nagata A. The clinical significance of colonoscopy in hemorrhagic colitis due to enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157: H7 infection. Endoscopy. 2002;34:311–314. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khuroo MS, Mahajan R, Zargar SA, Panhotra BR, Bhat RL, Javid G, Mahajan B. The colon in shigellosis: serial colonoscopic appearances in Shigella dysenteriae I. Endoscopy. 1990;22:35–38. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1012784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi Y, Yamamoto H, Kita H, Sunada K, Sato H, Yano T, Iwamoto M, Sekine Y, Miyata T, Kuno A, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small bowel injuries identified by double-balloon endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4861–4864. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i31.4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]