Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells disrupt the healthy bone marrow microenvironment to create a leukemic niche that is crucial for facilitating leukemogenesis and protects leukemic cells from chemotherapeutic agents and immune cells.1, 2 However, the functional mechanisms that regulate this malignant process are largely unknown. Recently, we showed that tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) play an important role in the communication between leukemic cells and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs).3, 4 TNTs are thin membrane protrusions that are driven by the actin cytoskeleton.5 We recently showed that ALL cells use TNTs to signal toward MSCs and subsequently induce the secretion of pro-survival cytokines, leukemic cell survival and drug resistance.4 B-cell precursor ALL (BCP-ALL) cells and MSCs exchange lipophilic molecules using TNTs.4 However, the identity of the transported cargo needs further elucidation. In this study, we describe that autophagosomes, mitochondria and the transmembrane protein ICAM1 are transferred from BCP-ALL cells toward MSCs in a TNT-dependent manner.

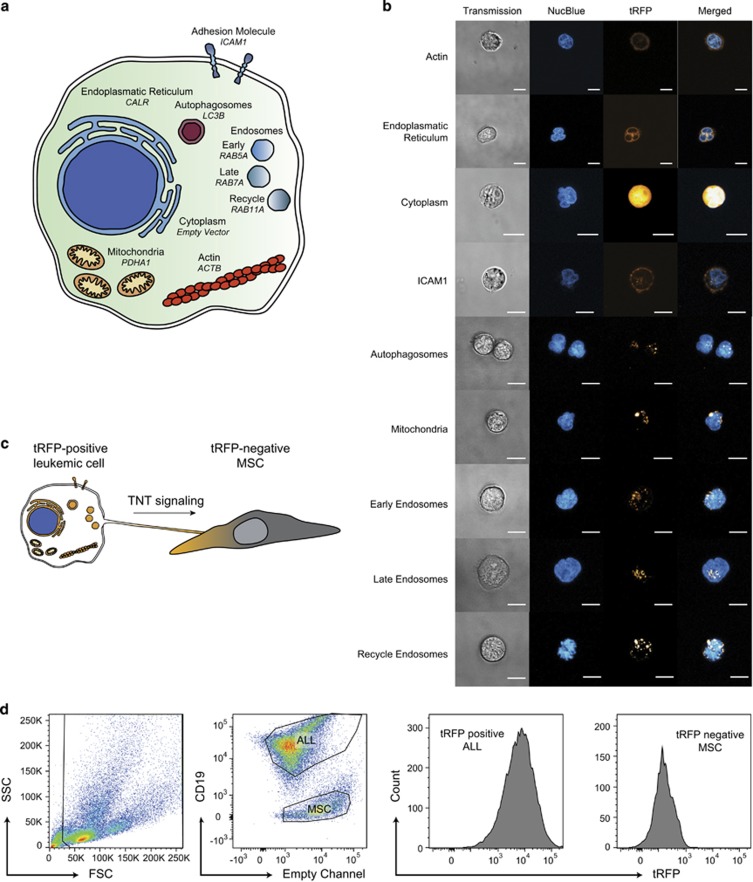

To identify which structures are transferred from leukemic cells to MSCs via TNTs, we ectopically (that is, non-endogenously) expressed fluorescently tagged proteins that mark specific cellular structures in BCP-ALL cells (NALM6) using lentiviral vectors (Figure 1a; Supplementary Figure 1). After lentiviral transduction, we obtained stable BCP-ALL cell clones expressing turbo RFP (tRFP)-tagged marker proteins. The tRFP-positive BCP-ALL cells were stained with a nucleus specific dye (NucBlue), after which specific subcellular localization of fluorescent marker proteins was confirmed by confocal microscopy (Figure 1b). For example, CALR, which marks the endoplasmatic reticulum, was expressed at the nuclear border (Figure 1b second panel from the top).

Figure 1.

Identifying TNT cargo using fluorescently tagged proteins. (a) Schematic overview of ectopically expressed marker proteins that were used to visualize specific cellular structures in BCP-ALL cells (NALM6). (b) Representative confocal images showing the subcellular localization of tRFP-positive marker proteins relative to the nucleus in live NALM6 cells. A transmission image is provided to show the shape of the leukemic cell (left panel). (c) Experimental setup for visualizing protein transfer from BCP-ALL cells toward MSCs. Leukemic clones that express tRFP-positive marker proteins were co-cultured with tRFP-negative MSCs and transfer of protein toward was quantified by flow cytometry. (d) Gating strategy that was used to quantify transfer of tRFP-positive marker protein from leukemic cells toward MSCs by flow cytometry. BCP-ALL cells and MSCs are gated based on their forward and sideward scatter (first panel), and separated based on CD19 expression (second panel). Finally, the median tRFP signal in MSCs was quantified with the phycoerythrin channel and used as a measure of tRFP-positive marker protein transfer (last panel). See also Supplementary Figure 1.

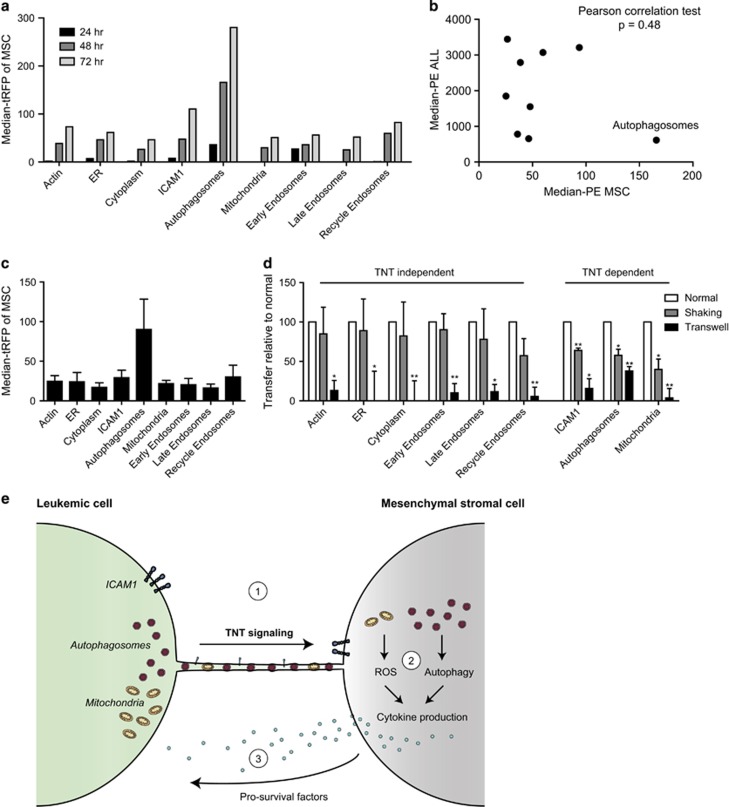

Next, we co-cultured tRFP-marker protein expressing BCP-ALL cells with tRFP-negative MSCs (Figure 1c) and quantified the transfer of tRFP by flow cytometry (Figure 1d). The B-cell marker CD19 was used to distinguish between BCP-ALL cells and MSCs (Figure 1d, second panel). Actin, endoplasmatic reticulum, cytoplasm, ICAM1, autophagosomes, mitochondria and early/late/recycle endosomes were transferred from BCP-ALL cells to MSCs, since MSCs became increasingly positive for tRFP signal after co-culture with tRFP-tagged leukemic clones for 24, 48 and 72 h (Figure 2a). To exclude that tRFP transfer was non-specific, we plotted the intensity of tRFP in BCP-ALL cells, that differed 6.9-fold between the brightest and dimmest clone (cytoplasm versus endoplasmatic reticulum; Supplementary Figure 2), against the intensity of tRFP in MSCs after co-culture for 48 h (Figure 2b). No correlation was found between the amount of transfer and the intensity of the tRFP signal in the leukemic clone from which the tRFP-tagged molecule originated (Figure 2b; P=0.48, Pearson correlation test), showing that the observed transfer is not explained by non-specific leakage of tRFP label. This implies that tRFP transfer from BCP-ALL cells toward MSCs is representative for transfer of tagged cellular structures. Autophagosomes appeared to be the most highly transported structure from BCP-ALL cells to MSCs (three-fold more than other proteins after 48 h; Figure 2c). To assess the contribution of TNTs to the transfer of cellular structures, we performed ALL-MSC co-cultures in the absence or presence of TNT inhibiting conditions for 48 h. TNTs were inhibited by two established approaches in literature: mechanical disruption of TNTs through gentle shaking of cell cultures and physical separation of BCP-ALL cells, and MSCs using a transwell system (3.0 μm pore size).4, 6 While actin inhibitors are often used to inhibit TNTs, their short half-time and high cytotoxicity prevented their use in these experiments.4 Transfer of actin (ACTB), endoplasmatic reticulum (CALR), cytoplasmic content (empty vector) and endosome markers (RAB family) were inhibited by transwell conditions, but not by gentle shaking (Figure 2d). This implicates that transfer of these proteins is driven by cell–cell signaling modules other than TNTs. For example by gap junctional protein Cx43, which has been shown to be involved in transfer of extracellular vesicles.7 Interestingly, transfer of transmembrane protein ICAM1, autophagosomes (LC3B) and mitochondria (PDHA1) was significantly inhibited by both TNT inhibiting conditions (shaking and transwell; P<0.05, Figure 2d). Transmembrane proteins and mitochondria have previously been observed to be transferred via TNTs by other cell types.8, 9 Our data show that this is also true for TNT signaling between BCP-ALL cells and MSCs. Strikingly, transfer of autophagosomes was three-fold higher than ICAM1 and PDHA1 transfer (Figure 2c). To our knowledge, this is the first time that autophagosome transfer is observed between ALL cells and MSC in a TNT-dependent manner.

Figure 2.

Autophagosomes, mitochondria and ICAM1 are transferred via tunneling nanotubes. (a) BCP-ALL cells expressing tRFP-markers were co-cultured with tRFP-negative MSCs for 24 (black bars), 48 (dark-gray bars) and 72 h (light-gray bars). Median intensity of MSCs for tRFP is shown. (b) Graph showing the median tRFP intensity of MSCs (xaxis) compared to BCP-ALL tRFP intensity (yaxis) after co-culture for 48 h as depicted in a. No correlation was found indicating that transfer of tRFP was protein specific (n=3, P=0.48, Pearson correlation test). (c) Graph showing the transfer of tRFP from BCP-ALL cells toward MSCs after 48 h of co-culture (n=3). (d) Graph showing the transfer of tRFP from BCP-ALL cells toward MSCs after TNT inhibition (gray and black bars), compared to normal co-culture conditions (white bars; n=3; one-tailed t-test, paired). (e) Model of TNT signaling in the leukemic niche: 1: Leukemic cells use TNT signaling to transfer autophagosomes, mitochondria and ICAM1 toward MSCs in their microenvironment. 2: Increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) and autophagy in MSCs induces the production of cytokines. 3: Supportive and nurturing factors are released into the tumor microenvironment, which induce survival and drug resistance in leukemic cells. Data are means±s.e.m.; *P⩽0.05, **P⩽0.01. See also Supplementary Figure 2. PE, phycoerythrin.

Autophagy is a process that degrades and recycles unwanted or damaged cellular components such as proteins and organelles.10 This process has been implicated as an important regulator of both tumor initiation and tumor suppression.11 Autophagy is driven by double-membraned vesicles known as autophagosomes, which are shaped through the actin cytoskeleton.12 TNT formation is also dependent on actin4, 5 and this co-dependence might be important for autophagosome transport through the TNT machinery. Interestingly, autophagy induction through starvation of cells has been shown to increase the formation of TNTs,13 suggesting a correlation between these processes. Recently, we observed that TNT signaling induces the secretion of pro-survival cytokines.4 Autophagy is a known regulator of cytokine signaling and this process is influenced by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and/or mitochondrial DNA.14 The transfer of mitochondria and autophagosomes from leukemic cells toward MSCs might therefore explain the release of supportive factors by the tumor microenvironment, as we recently reported elsewhere (Figure 2e).4 Interestingly, the transcription of ICAM1, a transmembrane protein involved in cell–cell adhesion, is known to be upregulated in response to cytokine signaling and reactive oxygen species.15 Its transport toward MSCs may provide anchorage to facilitate TNT function.

In conclusion, these data show the potential of using fluorescently labeled marker proteins to characterize which cellular structures are transported by TNT signaling from ALL cells to MSCs. Our study confirmed several known TNT cargo (that is, mitochondria and transmembrane proteins)8, 9 and revealed novel structures (autophagosomes) that are transported through TNTs. The TNT-dependent transfer of autophagosomes and mitochondria from ALL cells toward MSCs might unveil an important mechanism that leukemic cells use to affect their microenvironment. Our study suggests that instead of upregulating autophagy in an indirect manner, leukemic cells transfer autophagosomes to MSCs in order to enhance autophagy-induced cytokine secretion. In addition, our study identifies autophagosomes, ICAM1 and mitochondria as important structures that are actively transported from leukemic cells toward their microenvironment via TNTs.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the research laboratory Pediatric Oncology of the Erasmus MC for their help in processing mesenchymal stromal cell samples, in particular F Meijers-Stalpers; The Erasmus Optical Imaging Centre for providing support of CLSM, in particular G Kremers; The work described in this paper was funded by the KiKa Foundation (Stichting Kinderen Kankervrij—Kika-39), the Dutch Cancer Society (UVA 2008; 4265, EMCR 2010; 4687), the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO–VICI ML den Boer) and the Pediatric Oncology Foundation Rotterdam.

Author contributions

BdeR and Roel Polak designed the study, performed the experiments, collected and analyzed all data, and wrote the paper. FS performed additional experiments. MLdB and Rob Pieters analyzed data and wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and approved the submitted manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Leukemia website (http://www.nature.com/leu)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Colmone A, Amorim M, Pontier AL, Wang S, Jablonski E, Sipkins DA. Leukemic cells create bone marrow niches that disrupt the behavior of normal hematopoietic progenitor cells. Science 2008; 322: 1861–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakasone ES, Askautrud HA, Kees T, Park JH, Plaks V, Ewald AJ et al. Imaging tumor‐stroma interactions during chemotherapy reveals contributions of the microenvironment to resistance. Cancer Cell 2012; 21: 488–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, Scadden DT. The bone marrow niche for haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2014; 505: 327–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polak R, de Rooij B, Pieters R, den Boer ML. B‐cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells use tunneling nanotubes to orchestrate their microenvironment. Blood 2015; 126: 2404–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustom A, Saffrich R, Markovic I, Walther P, Gerdes HH. Nanotubular highways for intercellular organelle transport. Science 2004; 303: 1007–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowinski S, Jolly C, Berninghausen O, Purbhoo MA, Chauveau A, Kohler K et al. Membrane nanotubes physically connect T cells over long distances presenting a novel route for HIV‐1 transmission. Nat Cell Biol 2008; 10: 211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares AR, Martins‐Marques T, Ribeiro‐Rodrigues T, Ferreira JV, Catarino S, Pinho MJ et al. Gap junctional protein Cx43 is involved in the communication between extracellular vesicles and mammalian cells. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 13243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Gerdes HH. Transfer of mitochondria via tunneling nanotubes rescues apoptotic PC12 cells. Cell Death Differ 2015; 22: 1181–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainy N, Chetrit D, Rouger V, Vernitsky H, Rechavi O, Marguet D et al. H‐Ras transfers from B to T cells via tunneling nanotubes. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4: e726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 2011; 147: 728–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R, Karantza‐Wadsworth V, White E. Role of autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2007; 7: 961–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi N, Chen Y, Wang S, Chen M, Zhao M, Yang G et al. CapZ regulates autophagosomal membrane shaping by promoting actin assembly inside the isolation membrane. Nat Cell Biol 2015; 17: 1112–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou E, Fujisawa S, Morozov A, Barlas A, Romin Y, Dogan Y et al. Tunneling nanotubes provide a unique conduit for intercellular transfer of cellular contents in human malignant pleural mesothelioma. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e33093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. Autophagy and cytokines. Cytokine 2011; 56: 140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard AK, Rothlein R. Intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 (ICAM‐1) expression and cell signaling cascades. Free Radic Biol Med 2000; 128: 1379–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.