Abstract

Biomechanical studies have shown that medial meniscal root tears result in meniscal extrusion and increased tibiofemoral joint contact pressures, which can accelerate the progression of arthritis. Repair is generally recommended for acute injuries in the young, active patient population. The far more common presentation however, is a subacute root tear with medial meniscal extrusion in a middle aged patient. Coexisting arthritis is common in this population and complicates decision making. Treatment should be based on the severity of the underlying arthritis. In cases of early or minimal arthritis, root repair is ideal to improve symptoms and restore meniscal function. In patients with moderate or severe medial compartment arthritis, medial unloader bracing or injections can be tried initially. When non-operative treatment fails, high tibial osteotomy or arthroplasty is recommended. Long term clinical studies are needed to determine the natural history of medial meniscal root tears in middle aged patients and the best surgical option.

Key Words: Meniscus root tear, meniscus repair, medial meniscus, middle age, MMRT, arthritis

Introduction

There remains little doubt that the meniscus plays a crucial role for maintaining homeostasis of the knee joint. In addition to lubricating properties and providing secondary stability, the meniscus distributes significant load across the tibiofemoral joint.1,2 Current evidence suggests that tears of the meniscus disrupt normal homeostasis and increase contact force which can lead to premature arthritis.3-5

Injury to the root of the medial meniscus is a subtype of tear that may have profound impact on the health of the knee. Tears of the meniscus root insertion lead to meniscal extrusion, and subsequent loss of hoop stresses- an inherently critical structural property of the meniscus.6 Meniscus root tears creates profound changes in load transmission, and is biomechanical similar that of total meniscectomy.7 Although the true incidence is not known, medial meniscus root tears (MMRT) may occur in up to 10% of knees undergoing arthroscopy,8 with even higher rates in the Asian population. The average age of presentation nears 58 years old with risk factors being age, elevated body mass index (BMI), female sex and decreased activity level.9

Surgical techniques for root tears have evolved in recent times, with most techniques aimed at arthroscopic anatomic restoration of the root avulsion.10 While the biomechanical implications of a root tear seem to be clear, the clinical corollary of repair is less clear as outcomes haven’t been well substantiated; specifically in the middle aged population. Nevertheless, recognition of the tear, and a thorough understanding of the implications and coexisting joint pathology can help guide the treating physician in providing appropriate recommendations to patients.

In this review, we illustrate the clinical presentation, imaging findings, and discuss surgical decision making via a case based review to help expand the general knowledge base and facilitate treatment decision making for clinicians facing this challenging problem.

Background

Although medial meniscal root tears can occur in the setting of trauma or in association with acute ligamentous injury, they are much more commonly the result of a chronic process that occurs in middle-aged patients with a degenerative knee. Lateral root tears on the other hand, are more commonly associated with acute knee trauma and ligamentous injuries. Recent studies have also shown tears of the posterior root of the medial meniscus to be more common in patients with the following risk factors: increased age, female sex, sedentary lifestyle, obesity and overall varus mechanical alignment of the knee.9,11 MMRT’s can often be missed in these patients as there is usually not a history of trauma and often present with a subacute pain history.

Etiology

The relationship of chronic MMRT in the arthritic knee isn’ t well understood as it remains unclear whether meniscus root tear and extrusion is a cause or effect. Lerer reported that 20% of patients with extrusion of the medial meniscus had no or minimal evidence of degenerative joint disease, thus concluding that perhaps root tears precede arthritis.12 Still, others have found a significant correlation of advanced arthritis to MMRT, suggesting perhaps extrusion and tearing may be an effect of joint space narrowing, rather than cause. In a total knee arthroplasty study, Choi, et al found 78% of patients to have tears involving the root or posterior horn at the time of knee replacement surgery.13 Regardless of cause or effect of MMRT’s, there appears to be a correlation with medial arthritis of the knee, of which the relationship is important to appreciate.

Anatomy: Medial Meniscus

The medial meniscus is semicircular in shape, with a slightly broader region posteriorly. The anterior horn insertion is somewhat variable, and has an attachment to the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus, via the intermeniscal ligament and was seen in 50% of cadaveric knees, in at least one study.14 While the anterior horn only has inferior attachments to the tibia, the body of the meniscus has direct superior and inferior peripheral attachments to the capsule, which blends into the deep medial collateral ligament. The posterior horn of the meniscus loses its superior capsular attachments but inserts on the posterior tibia via the posterior root. According to recent anatomic studies, the root can reproducibly be located 9.6 mm posterior and 0.7 mm lateral from the medial tibial eminence. Alternatively, it can be found 3.5 mm lateral from the medial tibial plateau articular cartilage inflection point,15,16 which may serve as reliable arthroscopic location for fixation.

Biomechanics/Pathology

The menisci are fibrocartilaginous wedge-shaped discs that act as shock absorbers by distributing the force through circumferential hoop stresses. The menisci typically bear somewhere between 40-70% of the mechanical force that is transmitted through the knee joint.17-19 The meniscus also serves as an important secondary stabilizer of the knee, which helps to maintain normal knee kinematics and prevent degeneration of the cartilage.

A significantly greater mechanical load is seen by the posterior horn of the medial meniscus compared to the anterior, especially with the knee in flexion. This greater load leads to more frequent tears of the posterior root than anterior tears. Posterior root tears are also more biomechanically significant, as they can disrupt the essential shock-absorbing ability of the meniscus and render it unable to adequately transfer axial load into hoop stresses. The secondary stabilizing effects are also lost in the setting of a root tear. This inability to transfer load into hoop stresses and loss of stabilization in turn leads to abnormal knee kinematics.20 As a result, the meniscus can become extruded and the medial compartment of the joint is subjected to increased contact pressures over decreased contact surfaces, which can greatly accelerate the arthritic process. In recent biomechanical studies, the effect of a posterior root tear of the medial meniscus has even been compared to that of a total meniscectomy.21,22 Since meniscal root tears were first described in the literature by Pagnani et al. in 1991,23 there has been much effort and research focused on properly identifying and repairing these lesions if possible, with the purpose of preserving the articular surface of the medial compartment.

Imaging

Weight bearing radiographs are a standard in a painful knee workup and should include anteroposterior (AP), lateral (LAT), standing AP with 45° of knee flexion (Rosenberg view) and Merchant views. Long leg alignment films should also be considered to gain a better understanding of the mechanical axis if malalignment is suspected.

When radiographs rule out moderate to severe medial compartment arthritis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be considered as the clinical diagnosis of a root tear can be challenging. Extrusion of the meniscus, as seen on a coronal image, is often, but not always associated with meniscus root tear. If the peripheral meniscus edge is greater than 3 mm beyond the outer margin of the tibial surface it is said to be extruded and should tip the clinician off to a possible root injury (Figure 1). In a recent, large multicentered osteoarthritis study, Crema et al, found that MMRT was strongly associated with meniscus extrusion. In this study, they determined the presence of meniscus extrusion increased odds of root tear by a factor of 10.2.24

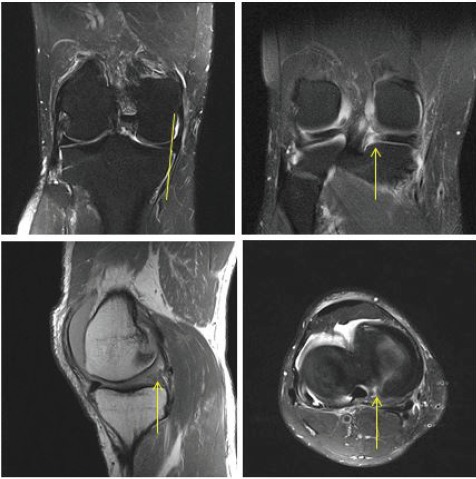

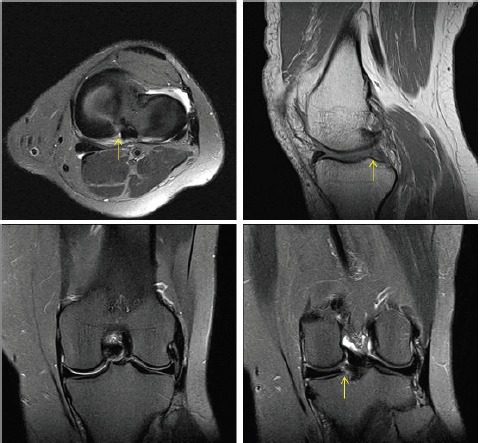

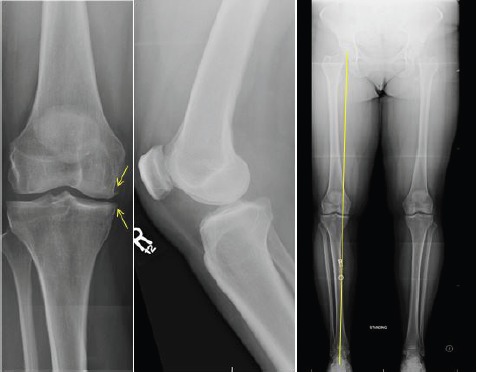

Figure 1:

Coronal T2 weighted image showing extrusion of the medial meniscus beyond the dimensions of the medial tibial plateau (upper left), while upper right image confirms avulsion of the root of the medial meniscus. A pathognomonic “ghost sign”, or segmental defect of the posterior root on T1 weighted sagittal MRI image (lower left), and a radial tear of the posterior root as seen on axial T2 weighted image (lower right).

The posterior horn of the medial meniscus can generally be visualized on MRI. Coronal T2 weighted images, which some have argued has the highest accuracy for diagnosing a tear.25 T1 sagittal images may be used to look for a “ghost sign” which represents either increased signal or absence of the typically dark signal found in the posterior meniscus root.18,19,26 Axial images are of value as well, and can be used to help visualize a tear (Figure 1). Choi et al reported very high diagnostic accuracy of MRI for detection of MMRT. Positive predictive values, negative predictive values, sensitivity and specificity of axial, coronal and sagittal were all >90%.27

Differentiation of a true root tear from paracentral radial tear should also be accomplished. While the blood supply to the root is abundant, the paracentral meniscus blood supply is more limited, and may not be as amenable to repair.28,29 (Figure 2) represents a comparison of a true root avulsion and a paracentral root tear. Although paracentral root tear may represent a different tear pattern, Laprade et al showed significantly increased mean contact pressures after radial tear 3, 6 and 9 mm from the root, making them essentially biomechanically equivalent to root tears.10

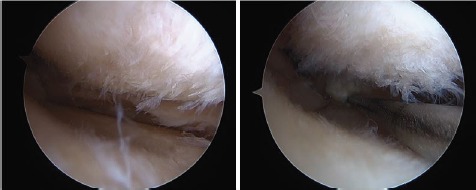

Figure 2:

Note true avulsion of the root (left), while the image on the right demonstrates a complete radial avulsion of the posterior horn, with remnant root still attached.

Associated MRI findings are commonly found in with MMRT. One study showed 97% of MRI’s obtained with a MMRT also had some evidence of degenerative joint disease. As expected, medial femoral condyle lesions were commonly observed.30 Increased femoral condyle stress related edema and subchondral collapse has also been observed and seems to have an association with MMRT’s.31 Furthermore, well defined bony ossicles within the meniscus substance have been reported in association with MMRT. In a retrospective imaging study of meniscal ossicles, Mohankumar et al reported 66% were found within the posterior root, and when an ossicle was present in the meniscus, a root tear was visualized in 74% of cases. It’s not clear however, whether ossicles are post traumatic, congenital or related to mucoid degeneration.32

In sum, associated pathology is frequent in this setting of MMRT, thus the overall cartilage health should be critically evaluated and considered by the clinician when considering treatment options.

CASES

Case 1: Non-operative management

A 55 year old farmer presented with chronic, posteromedial pain in his left knee pain without clear injury history. His exam was notable for mild posteromedial joint line tenderness. Ligamentous exam was normal. Radiographs demonstrated mild medial joint line narrowing, worse on Rosenberg views. MRI of his left knee demonstrated meniscus root tear with significant extrusion and full thickness medial femoral cartilage loss. Given the degree of arthrosis, he was counseled about treatment options and elected for non-operative management. He ultimately underwent a series of steroid injections and was able to return to activities and work without limitation. Interestingly, he presented 7 years later after an acute injury to the contralateral, right knee and was found to have an acute, extruded menisus root tear. A screening xray of his left knee was acquired, and as seen in the serial radiograph, his arthritis has progressed significantly over time. Nevertheless, his left knee remains asymptomatic (Figure 3).

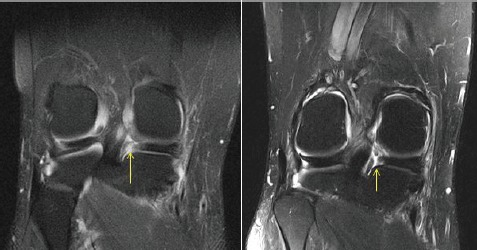

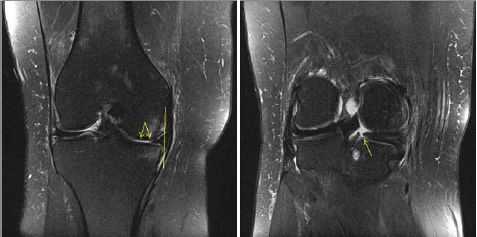

Figure 3:

Rosenberg x-ray (left) demonstrating mild joint line narrowing. T2 weighted coronal MRI (middle) shows meniscus extrusion with medial femoral condyle defect and was thus treated non-operatively. The patient was seen 7 years later for increasing contralateral knee pain and underwent screening x-rays showing progression of medial arthritis (right). It should be noted that he remains asymptomatic despite radiographic progression of arthritis.

Non operative management of a MMRT should be considered in the setting of advanced arthritis, those unable or unwilling to comply with postoperative rehab or those that are poor surgical candidates. Non surgical measures to consider include non steroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDs), corticosteroid injection therapy, activity modifications, medial unloader bracing, physical therapy (PT) and weight loss management.

Non operative treatment with NSAIDs and supervised PT has been shown to be effective at controlling symptoms in at least two, retrospective level IV studies. Kim, et al treated 30 patients with MMRT (mean age of 59) with PT and NSAIDs for 8- 12 weeks and showed improved symptoms up to 12 months.33 The authors reported a slight decline in clinical scores thereafter. Neogi, et al reported their experience with NSAIDs and PT treatment of MMRT’s in 33 patients with an average age of 55.8 years old. The authors noted clinical improvements for 6 months, however a gradual clinical decline and advancement of arthritis by x-ray was observed at 35 months. Nevertheless, final follow up was still significantly improved from pre-treatment status.34 A recent study by Krych, et al showed non operative management of MMRT to have a very high failure rate, with 31% of patients undergoing arthroplasty by 30 months after and an overall failure rate of 87%36.

In sum, non-surgical management should be initiated in patients with moderate to severe arthritis, or those who are not surgical candidates, however as progression of arthritis is common, counseling about arthritis progression should be undertaken.

Case 2: partial menisectomy

A 46 yo M pipeline welder presented with 3 months of worsening knee pain that initially began while running on a treadmill. He experienced medial sided pain and swelling since, which was made worse with stairs and deep squatting. He received physical therapy and a steroid injection with limited pain relief through his primary care provider. Upon referral, the exam was notable for medial joint line tenderness and ligamentous stability. Radiographs showed Kellegren-Lawrence grade II medial arthritis. MRI demonstrated a MMRT with extrusion of 4 mm. Tibiofemoral cartilage was diffusely thinned medially (Figure 4). Preoperatively he was counseled about meniscectomy versus repair, pending the status of his cartilage. At arthroscopy, diffuse Grade II/III Outerbridge chondromalacia was noted, thus partial meniscectomy was performed (Figure 5). Postoperatively, he was advanced to weight bearing as tolerated and returned to activities gradually. By 12 weeks post op he was largely pain free and had returned to work without difficulty. At 6 mo post op he continued to be asymptomatic and was counseled about the long term status of his knee. He returned at 1 year post op with increased medial sided knee pain and was found to have advanced arthritis of the knee. He ultimately underwent steroid injection therapy, but was referred on for consideration of unicompartmental arthroplasty.

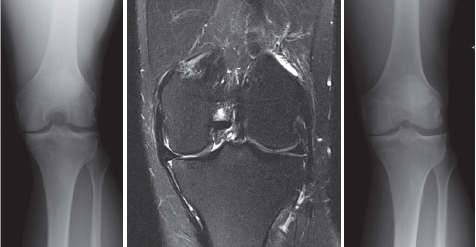

Figure 4:

AP, Rosenberg and lateral radiographs (top) demonstrating mild medial joint line narrowing. MRI demonstrating root tear and extrusion with diffuse cartilage thinning medially.

Figure 5:

Arthroscopic images at time of surgery demonstrate diffuse, Outerbridge Grade II/III chondromalacia, with meniscus root avulsion noted (left). Given the state of the cartilage, meniscus debridement was performed.

Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy can be considered for symptomatic relief, when repair cannot be achieved or the arthritis is too advanced. Ozcok et al reported modest improvements in symptoms out to 56 months in a study of 67 patients undergoing meniscectomy for MMRT (average age 55.8 yrs). While Lysholm knee scores improved from 53 to 67 at follow up, the authors did observe advancement of Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) grade arthritis from an average of 2 to 3 at final follow up.8

In another level IV study, Han et al reported longer term data on 46 patients with MMRT that underwent meniscectomy. Unfortunately, at an average of 77 months post op, only 56% of patient reported improvement in pain, while 67% were satisfied and 19% required re-operation. 35% of patients showed progression of arthritis by KL grade35.

Kim et al, reported a level III comparative study of 58 patients that underwent either partial meniscectomy or root repair. Although meniscectomy and repair were both improved from preoperative state at close to 4 year follow up, the meniscectomy group had more radiographic progression of arthritis compared to the repair group (30% vs 75%, p<.05)36.

In sum, meniscectomy can be considered for symptomatic relief when MMRT is present in the setting of mild to moderate arthritis. Patient counseling about the likely early clinical benefits, but probable mid to late term arthritic changes should be performed.

Case 3: Root Repair

46 year old female homemaker presents with 10 months of significant left knee pain, located in the posteromedial knee after stepping into a pothole. She received one prior steroid injection from her primary care provider that provided limited pain relief. The exam was notable for posteromedial joint line tenderness and significant pain with deep knee flexion. Thessaly test for meniscus tear was positive. Ligamentous exam was reassuring. Radiographs revealed preserved joint line and no malalignment (Figure 6). MRI showed tear of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus (Figure 7). She underwent arthroscopic repair of the meniscus root with transtibial pullout repair technique (Figure 8). She was made non weight bearing for 6 weeks, with restrictions in motion to 90 degrees. Weight bearing and range of motion were progressed thereafter and she returned to all activities by 6 months post op.

Figure 6:

Standing AP, Rosenberg and lateral radiographs demonstrating minimal medial joint line narrowing. Mechanical axis is neutral on AP long-leg x-ray.

Figure 7:

Axial T2, sagittal T1, and coronal T2 weighted images demonstrating complete root avulsion with no significant cartilage loss.

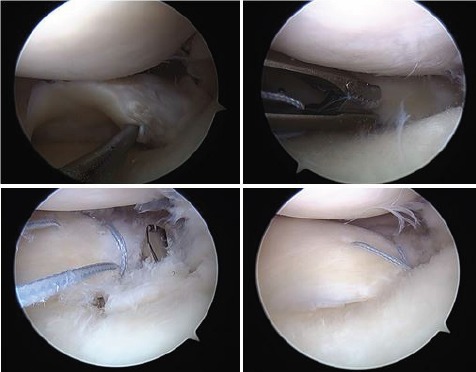

Figure 8:

Arthroscopic images of the right knee revealing displaced, avulsion of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus (upper left). Note the preserved cartilage. Figure-of-eight stitch passed through the meniscus root (upper right). A 5 mm tunnel drilled inside out from the medial tibia in the root anatomic footprint (lower left). Sutures then retrieved through the tunnel and secured over a cortical button on the medial tibia, thus repairing root tear to its footprint.

Clinical data after surgical root repair is sparse and largely limited to retrospective series. In a level IV study, Lee, at al reported data on 20 patients with MMRT that underwent repair with a minimum 2 year follow up. At almost 32 month average follow up, they showed significant clinical improvement with only one patient showing radiographic progression of arthritis and 1 patient re-tearing at 6 mo post op. Additionally, second-look arthroscopy was performed on 10 patients and complete healing of the root was noted in all 37. In contrast, Seo et al reported 21 patients that underwent medial meniscus root repair but in their study, found no cases of complete healing during second-look arthroscopies at 13 mo average follow up. It should be recognized that his study did include patients with varus alignment and grade III/IV Outerbridge chondromalacia that required osteotomy. Despite high rates of incomplete healing, average clinical scores showed significant improvement at follow up38.

Surgical Technique

Several modifications in surgical repair of MMRT have occurred in recent years, but most treatment is aimed at restoring the root attachment via a suture anchor or through transtibial bone tunnels. Transosseus repair techniques, such as the transtibial pullout repair have gained popularity, and has been our preferred practice (Figure 9). Standard medial and lateral parapatellar arthroscopic portals are created and the torn meniscus stump is debrided down to a bleeding bone trough with an arthroscopic shaver. If access into the medial joint space is limited, pie crusting the femoral side of the MCL from outside-in with a spinal needle can help to enhance the working space. No. 2 non-absorbable suture is then passed through the meniscus root using a suture passing device. We prefer to use a Knee Scorpion (Arthrex, Naples, FL) for suture passage. Various stitch configurations have been described, but we prefer a figure-of-8 pattern. Sutures are thereafter retrieved from the lateral portal. An anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) guide is introduced from the medial portal, and centered on the root footprint. A guide pin is advanced from the proximal medial or lateral tibia to the ACL guide tip. A 5 mm tunnel is drilled over the guide pin, carefully breaching the tibial surface. Alternatively, a retrograde reaming device may be used to drill a socket for which the root may be dunked within. Sutures are then retrieved through the tunnel (we prefer a Hewson suture passer) and shuttled exteriorly where they are secured over a plate, screw or cortical button.

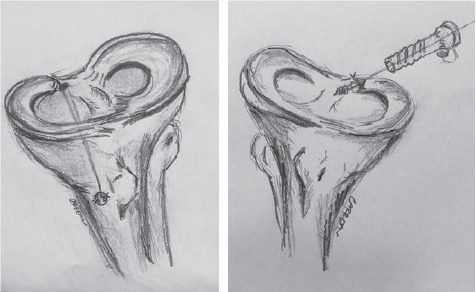

Figure 9:

Trans-tibial pullout technique (left) and suture anchor technique (right).

Suture anchor techniques on the other hand, involve establishing an accessory posteromedial portal to gain access to the posterior root (Figure 9). A suture anchor can be placed at the anatomic root location through the accessory posteromedial portal. Similar to the transtibial technique, sutures may then be passed through the root, shuttled between portals, and tied all inside using a knot pusher.

Several biomechanical studies investigating these techniques have been performed. Allaire et al showed peak contact pressures within the tibiofemoral joint were restored to normal after transtibial pullout root repair at 0, 30, 60 and 90 of knee flexion7. Marzo and Gurske-DePerio showed similar findings with significant increases in mean peak contact pressures after tear and restoration of loading profiles equal to that of the control knee after repair6. At least one biomechanical study has compared transtibial pullout to suture anchor fixation. Feucht et al performed a cadaveric study which revealed suture anchor repair to have lower displacement and higher stiffness after 100, 500 and 1000 cyles then transtibial pullout repair. Neither technique was effective at reaching native strength of the intact medial meniscus root, however39.

There remains little clinical data comparing different surgical techniques. One recent prospective study however, has been performed comparing the two techniques. Kim at al compared 22 patients that underwent transtibial pullout to 23 patients that underwent suture anchor repair of MMRT. At 2 years follow up, there didn’t appear to be statistically significant differences in the repair techniques when evaluating functional improvement or healing rates. Both techniques resulted in significant improvements from preoperative state ( p<.05)40.

Case 4: High Tibial Osteotomy

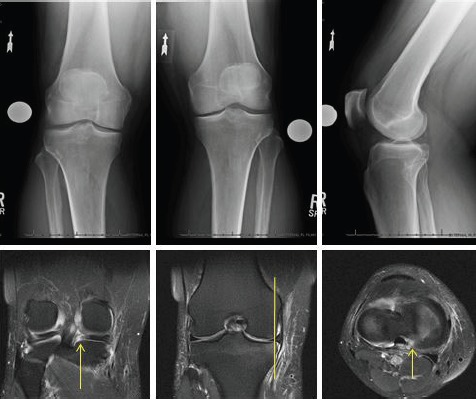

A 44 year old female teacher presented to our clinic with 8 weeks of medial sided knee pain without a clear injury. She was quite active, and prior to this was able to run 6-8 miles per week. She received one previous steroid injection by her primary care provider, which provided limited pain relief. Examination was notable for medial joint line tenderness and ligamentous stability. Radiographs revealed mild medial joint line narrowing, and varus alignment (Figure 10). MRI revealed paracentral medial meniscus root tear with extrusion and diffuse changes of the medial tibiofemoral joint, with preserved lateral cartilage (Figure 11). Given the varus alignment, moderate cartilage loss, and paracentral nature of the tear, she was offered an arthroscopic meniscectomy with high tibial osteotomy to unload her medial knee joint. At the time of arthroscopy, Outerbridge grade III/ IV arthritis was evident within the medial compartment but her lateral joint space was preserved. She underwent debridement of the meniscus tear and high tibial osteotomy for correction of her varus. By 6 months post op, she was back to swimming, biking and ice skating without any knee pain (Figure 12).

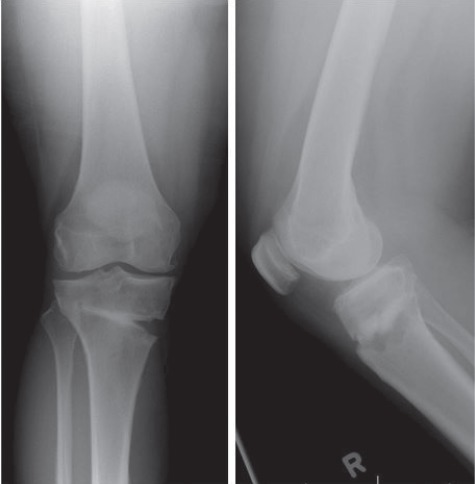

Figure 10:

AP and lateral radiographs demonstrate mild medial joint line narrowing with early osteophytes. Mechanical axis passes medial to the center of the knee, which measured 5 degrees of varus (right).

Figure 11:

T2-weighted coronal images demonstrating near full thickness cartilage loss from both the medial femoral condyle and medial plateau with 3.8 mm of extrusion of the medial meniscus (left). Note the radial tear is seen at the junction of the posterior body and root (right).

Figure 12:

AP and lateral radiographs taken 6 months post-op, after high tibial osteotomy (iBalance, Arthrex, Naples, Fl)

In this case, the patient had far too advanced arthritis and an unfavorable tear pattern to consider meniscus repair. Furthermore, her desired activity level was not amenable to arthroplasty, thus an osteotomy was offered for treatment.

In a level IV study, Moon et al reported 51 patients that underwent MMRT repair. At mean follow up of 33 months, those with Outerbridge grade 3 or 4 chondral changes and those with genu varum > 5° were associated with poorer outcome after root repair. These were both independent risk factors for inferior clinical outcome (p <.05)41.

In a noteworthy level IV study, Nha et al performed second look arthroscopies on 20 patients that underwent high tibial osteotomy for medial arthritis and MMRT. At arthroscopy, 50% of the root tears were completely healed despite no previous attempt at direct repair at the time of HTO. Interestingly, there was no correlation between healing rate and clinical outcome42.

In sum, in the setting of KL grade III/IV arthritis or significant varus alignment, salvage operations such as HTO or arthroplasty should be considered if conservative measures fail.

Summary

Tears of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus in the middle aged patient present a challenging clinical problem. As highlighted in the cases presented, clinical decision making in the middle aged individual should be based on degree of associated pathology and patient activity level and goals. Biomechanical studies clearly show that these tears lead to loss of hoop stress and extrusion, which profoundly impact the contact pressures within the knee. It’s postulated that this may advance joint degeneration, however long term studies about the natural history of these tears are needed. Clinical outcomes for both non operative treatment and meniscectomy are largely limited to retrospective case series. These methods do seem to offer short term clinical benefit, but progression of arthritis seems probable. The biomechanical evidence for repair on the other hand is strong, however long term clinical data supporting repair is quite limited and what role if any repair plays in slowing or reversal of arthritis of the knee is not understood. Regardless of the treatment rendered, the patient should be educated on the consequence of a MMRT, as progression of arthritis is common.

In summary, patients with a MMRT should undergo careful and critical evaluation of the cartilage within the knee. If moderate chondral loss is present, salvage options such as osteotomy or arthroplasty should be considered in conjunction with the patient’s activities and goals in mind. Future studies aimed at improving our understanding of what role surgery plays in the treatment of medial meniscus root tears in the middle aged patient is warranted.

References

- 1.Walker PS, Erkiuan Margaret J. “The role of the menisci in force transmission across the knee.”. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 109. 1975:184–192. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197506000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makris EA, Hadidi Pasha, Athanasiou Kyriacos A. “The knee meniscus: structure–function, pathophysiology, current repair techniques, and prospects for regeneration.”. Biomaterials. 2011;32(30):7411–7431. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alford JW, Lewis Paul, Kang Richard W., Cole Brian J. “Rapid progression of chondral disease in the lateral compartment of the knee following meniscectomy.”. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2005;21(no. 12):1505–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tapper EM, HOOVER NORMAN W. “Late results after meniscectomy.”. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51(3):517–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairbank TJKjcamJoBJS. 1948;Volume 30(no. 4):664–670. British. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marzo JM, Gurske-DePerio Jennifer. “Effects of medial meniscus posterior horn avulsion and repair on tibiofemoral contact area and peak contact pressure with clinical implications.”. The American journal of sports medicine. 2009;37(1):124–129. doi: 10.1177/0363546508323254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allaire R, Muriuki Muturi, Gilbertson Lars, Harner Christopher D. “Biomechanical consequences of a tear of the posterior root of the medial meniscus.”. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 2008;90(no. 9):1922–1931. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozkoc G, Circi Esra, Gonc Ugur, Irgit Kaan, Pourbagher Aysin, Tandogan Reha N. “Radial tears in the root of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus.”. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2008;16(no. 9):849–854. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0569-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang B-Y, Sung-Jae Kim, Lee Sang-Won, Lee Ha-Eun, Lee Choon-Key, Hunter David J., Jung Kwang-Am. “Risk factors for medial meniscus posterior root tear.”. The American journal of sports medicine. 2012;40(no. 7):1606–1610. doi: 10.1177/0363546512447792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaPrade RF, LaPrade Christopher M., James Evan W. “Recent advances in posterior meniscal root repair techniques.”. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2015;23(2):71–76. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doherty DB, Lowe WR. Meniscal Root Tears: Identification and Repair. American journal of orthopedics (Belle Mead, N.J.) Mar-Apr 2016;45(3):183–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lerer DB, Umans HR, Hu MX, Jones MH. The role of meniscal root pathology and radial meniscal tear in medial meniscal extrusion. Skeletal radiology. Oct 2004;33(10):569–574. doi: 10.1007/s00256-004-0761-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi E-S, Park Sang-Jun. “Clinical evaluation of the root tear of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus in total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis.”. Knee surgery & related research. 2015;27(no. 2):90–94. doi: 10.5792/ksrr.2015.27.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaPrade CM, Ellman Michael B., Rasmussen Matthew T., James Evan W., Wijdicks Coen A., Engebretsen Lars, LaPrade Robert F. “Anatomy of the Anterior Root Attachments of the Medial and Lateral Menisci A Quantitative Analysis.”. The American journal of sports medicine. 2014;42(no. 10):2386–2392. doi: 10.1177/0363546514544678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johannsen AM, Civitarese David M., Padalecki Jeffrey R., Goldsmith Mary T., Wijdicks Coen A., LaPrade Robert F. “Qualitative and quantitative anatomic analysis of the posterior root attachments of the medial and lateral menisci.”. The American journal of sports medicine. 2012;40(no. 10):2342–2347. doi: 10.1177/0363546512457642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smigielski R, Roland Becker, Zdanowicz Urszula, Ciszek Bogdan. “Medial meniscus anatomy—from basic science to treatment.”. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2015;23(no. 1):8–14. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3476-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shrive NG, O’Connor JJ, Goodfellow JW. Loadbearing in the knee joint. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. Mar-Apr 1978;131:279–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seedhom BB. Transmission of the Load in the Knee Joint with Special Reference to the Role of the Menisci: Part I: Anatomy, Analysis and Apparatus. Engineering in Medicine. 1979;8(4):207–219. October 1, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed AM, Burke DL. In-Vitro of Measurement of Static Pressure Distribution in Synovial Joints—Part I: Tibial Surface of the Knee. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 1983;105(3):216–225. doi: 10.1115/1.3138409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaPrade RF, LaPrade CM, Ellman MB, Turnbull TL, Cerminara AJ, Wijdicks CA. Cyclic displacement after meniscal root repair fixation: a human biomechanical evaluation. The American journal of sports medicine. Apr 2015;43(4):892–898. doi: 10.1177/0363546514562554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SB, Ha JK, Lee SW, et al. Medial meniscus root tear refixation: comparison of clinical, radiologic, and arthroscopic findings with medial meniscectomy. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. Mar 2011;27(3):346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allaire R, Muriuki M, Gilbertson L, Harner CD. Biomechanical consequences of a tear of the posterior root of the medial meniscus. Similar to total meniscectomy. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. Sep 2008;90(9):1922–1931. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00748. American volume. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pagnani MJ, Cooper DE, Warren RF. Extrusion of the medial meniscus. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 1991;7(3):297–300. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(91)90131-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crema MD, Roemer Frank W., Felson David T., Englund Martin, Wang Ke, Jarraya Mohamed, Nevitt Michael C., et al. “Factors associated with meniscal extrusion in knees with or at risk for osteoarthritis: the Multicenter Osteoarthritis study.”. Radiology. 2012;264(no. 2):494–503. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12110986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SY, Won-Hee Jee, Kim Jung-Man. “Radial tear of the medial meniscal root: reliability and accuracy of MRI for diagnosis.”. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2008;191(no. 1):81–85. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. <283.full.pdf>.

- 27.Choi S-H, Sooho Bae, Kyeong Ji Suk, Jong Chang Moon. “The MRI findings of meniscal root tear of the medial meniscus: emphasis on coronal, sagittal and axial images.”. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2012;20(no. 10):2098–2103. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1794-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koenig JH, Ranawat Anil S., Umans Hilary R., DiFelice Gregory S. “Meniscal root tears: diagnosis and treatment.”. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2009;25(no. 9):1025–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnoczky SP, Warren Russell F. “Microvasculature of the human meniscus.”. The American journal of sports medicine. 1982;10(no. 2):90–95. doi: 10.1177/036354658201000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee YG, Shim Jae-Chan, Sun Choi Yun, Goo Kim Jin, Jai Lee Ghi, Kyun Kim Ho. “Magnetic resonance imaging findings of surgically proven medial meniscus root tear: tear configuration and associated knee abnormalities.”. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2008;32(no. 3):452–457. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31812f4eb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sung JH, Ku Ha Jeong, Won Lee Dhong, Yeong Seo Won, Goo Kim Jin. “Meniscal extrusion and spontaneous osteonecrosis with root tear of medial meniscus: comparison with horizontal tear.”. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2013;29(no. 4):726–732. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohankumar R, Palisch Andrew, Khan Waseem, White Lawrence M., Morrison William B. “Meniscal ossicle: posttraumatic origin and association with posterior meniscal root tears.”. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2014;203(no. 5):1040–1046. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim HC, Hoon Bae Ji, Ho Wang Joon, Woo Seok Chang, Keun Kim Min. “Non-operative treatment of degenerative posterior root tear of the medial meniscus.”. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2010;18(no. 4):535–539. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0891-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neogi DS, Kumar Ashok, Rijal Laxman, Shekhar Yadav Chandra, Jaiman Ashish, Lal Nag Hira. “Role of nonoperative treatment in managing degenerative tears of the medial meniscus posterior root.”. Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology. 2013;14(no. 3):193–199. doi: 10.1007/s10195-013-0234-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han SB, Shetty Gautam M., Hee Lee Dae, Ju Chae Dong, Suk Seo Seung, Hyun Wang Kook, Hoon Yoo Si, Wook Nha Kyung. “Unfavorable results of partial meniscectomy for complete posterior medial meniscus root tear with early osteoarthritis: a 5-to 8-year follow-up study.”. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2010;26(no. 10):1326–1332. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SB, Ku Ha Jeong, Won Lee Soo, Won Kim Deok, Chan Shim Jae, Goo Kim Jin, Young Lee Mi. “Medial meniscus root tear refixation: comparison of clinical, radiologic, and arthroscopic findings with medial meniscectomy.”. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2011;27(no. 3):346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JH, Jin Lim Young, Bum Kim Ki, Hyung Kim Kyu, Hun Song Ji. “Arthroscopic pullout suture repair of posterior root tear of the medial meniscus: radiographic and clinical results with a 2-year follow-up.”. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2009;25(no. 9):951–958. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seo H-S, Su-Chan Lee, Kwang-Am Jung. “Second-look arthroscopic findings after repairs of posterior root tears of the medial meniscus.”. The American journal of sports medicine. 2011;39(no. 1):99–107. doi: 10.1177/0363546510382225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feucht MJ, Grande Eduardo, Brunhuber Johannes, Rosenstiel Nikolaus, Burgkart Rainer, Imhoff Andreas B., Braun Sepp. “Biomechanical comparison between suture anchor and transtibial pull-out repair for posterior medial meniscus root tears.”. The American journal of sports medicine. 2014;42(no. 1):187–193. doi: 10.1177/0363546513502946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim J-H, Ju-Hwan Chung, Dong-Hoon Lee, Yoon-Seok Lee, Jung-Ryul Kim, Keun-Jung Ryu. “Arthroscopic suture anchor repair versus pullout suture repair in posterior root tear of the medial meniscus: a prospective comparison study.”. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2011;27(no. 12):1644–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moon H-K, Yong-Gon Koh, Yong-Chan Kim, Young-Sik Park, Seung-Bae Jo, Sae-Kwang Kwon. “Prognostic factors of arthroscopic pull-out repair for a posterior root tear of the medial meniscus.”. The American journal of sports medicine. 2012;40(no. 5):1138–1143. doi: 10.1177/0363546511435622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nha K-W, Yong Seuk Lee, Dae-Hee Hwang, Ho Kwon Jae, Ju Chae Dong, Jee Park Young, In Kim Jong. “Second-look arthroscopic findings after open-wedge high tibia osteotomy focusing on the posterior root tears of the medial meniscus.”. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2013;29(no. 2):226–231. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]