Abstract

Introduction:

Spinal fusion surgery is an effective but costly treatment for select spinal pathology. Historically iliac crest bone graft (ICBG) has remained the gold standard for achieving successful arthrodesis. Given well-established morbidity autograft harvest, multiple bone graft replacements, void fillers, and extenders have been developed. The objective of this study was to evaluate the in vivo efficacy and safety of two mineralized collagen bone void filler materials similar in composition. Both bone void fillers were composed of hydroxyapatite (HA), tricalcium phosphate (TCP) and bovine collagen. The first test article (Bi-Ostetic bioactive glass foam or “45S5”) also contained 45S5 bioactive glass particles while the second test article (Formagraft or “FG”) did not. 45S5 and FG were combined with bone marrow aspirate and iliac crest autograft and compared to ICBG in an established posterolateral spine fusion rabbit model.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty-nine mature New Zealand White rabbits were divided into 3 test cohorts: ICBG, 45S5, and FG. A Posterolateral fusion model previous validated was utilized to assess fusion efficacy. The test groups were evaluated for spine fusion rate, new bone formation, graft resorption and inflammatory response using radiographic, μCT, biomechanical and histological endpoints at 4, 8 and 12 weeks following implantation.

Results

There were 4 clinical complications unrelated to the graft materials and were evenly split between groups (ICBG graft harvest complications; hind limb mobility, chronic pain) and were euthanized. These omissions did not affect the overall outcome of the study. Radiographic scoring of the fusion sites indicated a normal healing response in all test groups, with no adverse reactions and similar progressions of new bone formation observed over time. All groups demonstrated significantly less range of motion in both flexion/extension and lateral bending compared to normal not-fused controls, which supports fusion results observed in the other endpoints. Fusion occurred earlier in the 45S5 group: ICBG 0%, FG 0%, and 45S5 20% at 4 weeks; ICBG 43%, FG 38%, and 45S5 50% at 8 weeks; and ICBG 50%, FG 56%, and 45S5 56% at 12 weeks. Histopathology analysis of the fusion masses, from each test article and time point, indicated an expected normal response for resorbable calcium phosphate (HA/TCP) and collagen graft material. Mild inflammation with macrophage and multinucleated giant cell response to the graft material was evident in all test groups.

Discussion:

This study has confirmed the biocompatibility, safety, efficacy and bone healing characteristics of the HA-TCP collagen (with or without 45S5 bioactive glass) composites. The results show that the 3 test groups had equivalent long-term fusion performance and outcome at 12 weeks. However, the presence of 45S5 bioactive glass seemed to accelerate the fusion process as evidenced by the higher fusion rates at 4 and 8 weeks for the HA-TCP-collagen composite containing bioactive glass particles. The results also demonstrate that the HA-TCP-45S5 bioactive glass-collagen composite used as an extender closely mirrors the healing characteristics (i.e. amount and quality of bone) of the 100% autograft group.

Introduction

Spinal fusion surgery is an effective but costly treatment for spinal disorders. Successful long-term spinal arthrodesis requires inter-segmental stability. To achieve this, bone growth and maturation must occur across the spinal segments. Iliac crest autograft has been used for many years as a bone graft in spinal fusion despite issues associated with the quantity available and complications associated with the harvesting procedure1-11. Given morbidity associated with ICBG, alternatives and extenders have been developed. In general these can be classified as allografts, demineralized bone matrices, ceramics, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), and autologous growth factors. While the safety and efficacy of most of these substances have been extensively studied, the use of ceramic bone void fillers as a viable option for posterolateral spine fusions has not been fully established.

Calcium phosphate materials have been employed clinically as bone void fillers for decades. It was discovered that corals had a similar microarchitecture to bone12. From this, various ceramics including calcium sulfate, hydroxyapatite, calcium carbonate, and others were developed. These materials are most often provided in the form of small, porous granules that can be packed to fill the wide variety of size and shape of bony defects encountered. They lack osteogenic and osteoinductive properties, but ceramics allow for fibrovascular ingrowth of osteoid matrix via osteoconduction13. In spinal fusion surgery, several studies have demonstrated the clinical efficacy of ceramics as bone graft extenders14,15. Others have shown inferiority to ICBG alone16.

Recently, spongious strips of HA-TCP-45S5 bioactive glass-collagen composite (Bi-Ostetic bioactive glass foam) were developed by Berkeley Advanced Biomaterials by simply substituting some of the HA-TCP granules with 45S5 bioactive glass. The graft form allows for versatility in handling and ease-of-use. The strips can be hydrated with bone marrow aspirate (BMA) and/or extended with autograft. Such composite shows excellent osteoconduction and provides a scaffold for cell attachment, supporting the formation of osseous tissue across bony defects. The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of 45S5 bioactive glass combined with a HA-TCP-collagen matrix by comparing the in vivo performance of 2 bone void filler materials, Bi-Ostetic bioactive glass foam (45S5) and Formagraft (FG) in an established posterolateral spine fusion rabbit model using ICBG as a control. Performance was evaluated by specifically assessing fusion rates, new bone formation, graft resorption, and host inflammatory response.

Materials and Methods

A well-established rabbit posterolateral fusion model, previous validated by Boden et al.,17,18 was employed to assess fusion efficacy among two treatment and one control group. The test groups were evaluated for spine fusion rate, new bone formation, graft resorption and inflammatory response using radiographic, μCT, biomechanical and histological endpoints at 4, 8 and 12 weeks following implantation. A total of 69 mature New Zealand White rabbits were included into 3 groups: ICBG, 45S5, and FG. Each had 23 rabbits.

Group 1 (control): Iliac Crest Bone Graft (ICBG) Utilized autologous bone graft extracted from the iliac crest, morselized into 2-3 mm pieces.

Group 2: Formagraft (FG) Formagraft is a bone graft substitute consisting of resorbable purified fibrillar collagen and partially resorbable 60% HA – 40% TCP ceramic. The bovine fibrillar collagen component is biocompatible and has low immunogenicity. Formagraft strips were morselized into 2-3 mm pieces then mixed with bone marrow aspirate (BMA) and approximately 1.5 cc of morselized ICBG. The homogenous mix of FG-BMA-ICBG was molded into 3.0 cc rectangular blocks.

Group 3: Bi-Ostetic bioactive glass foam (45S5) 45S5 is composed of Bi-Ostetic (60%HA – 40%TCP) granules and 45S5 bioactive glass embedded in a bovine collagen matrix. 45S5 divided into 1.5 cc volumes was hydrated with 1.5cc BMA, and mixed with 1.5 cc of morselized ICBG. The homogenous mix of 45S5-BMA-ICBG was molded into 3.0 cc rectangular blocks.

Surgical Procedure

Each animal was under general anesthesia for initial surgical procedures. Appropriate antibiotic(s) were given throughout the conduct of the study. All animals were prepared for surgical procedures. After the pre-anesthetic had taken effect, rabbits were clipped free of fur over the surgical areas. The surgical areas were scrubbed with Chlorhexidine soap and wiped with isopropyl alcohol. Chlorhexidine solution was applied just prior to surgical incision.

The surgical approach to the spine was identical in all rabbits. A dorsal midline skin incision, approximately 15 centimeters long, was made from L1 to the sacrum, and then the fascia and muscle were incised over the L5-L6 transverse processes (TPs). The TPs were then decorticated with a high-speed burr. Approximately 3 cc of corticocancellous bone graft from the iliac crest was obtained bilaterally (~6 cc total). Approximately 3 cc per side of test article hydrated with bone marrow aspirate (BMA, 1.5 cc) + ICBG (1:1 ratio) were placed in the paraspinal bed between the TPs. Fascia and skin were closed with 3-0 Vicryl and the skin was stapled.

Radiographic Assessment

Ventral/dorsal radiographs were obtained with a Simon DR (Quantum) RAD-X High Frequency Radiographic Imaging System. Radiographs were examined to confirm graft placement, assess graft migration, osteolysis, fracture, or any other adverse events. In addition, radiographs were graded for bilateral fusion, new bone formation, and graft resorption. Radiographs were assessed by 3 blinded reviewers to determine unilateral and bilateral fusion rates for each study group at each time point. Both the left and right side fusion masses were graded as “fused” or “not fused” based on the presence of a continuous trabecular pattern within the intertransverse fusion mass17. Final fusion results were determined by agreement of at least 2 of the 3 observers. Radiographs were also scored bilaterally by 3 blinded reviewers for new bone formation and graft resorption per the scoring scale: none, some, moderate, and extensive.

Five specimens (histology animals) underwent μCT analysis. They were scanned using a SkyScan 1176 μ-CT using a similar technique as computerized tomography systems in medicine (MDCT-scans) but at a higher resolution (as thin as 9μm). X-ray images (2D) were acquired in multiple planes, internal structures were reconstructed as a series of 2D cross-sections that were then used to analyze the 2- and 3-dimensional morphological parameters of the specimen. Each specimen was analyzed for Total Area (TA), Bone Area (BA), Implant Area (GA), Soft Tissue Area (SA).

Necropsy

Animals were euthanized using Euthasol solution. Necropsy included examination of the external surface, all orifices, cranial, thoracic, abdominal and pelvic cavities including contents. The entire lumbar column was removed “en-bloc”. Soft tissues were immediately removed from the surgically treated spinal unit after the spine was dissected out of the body. The grafted site was examined for graft migration, infection, and soft tissue abnormalities. Spines from the 4 and 8-weeks animals were placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Spines from the 12-weeks animals were immediately tested for biomechanical stiffness.

Mechanical Testing

Biomechanical non-destructive stiffness testing was performed following manual palpation in the 12-weeks group. Testing consisted of flexion/extension, lateral bending, and torsion to a predetermined, sub-failure load.

The vertebral bodies cranial and caudal to the fused motion segment were embedded in Bondo/Fiberglass material using 2-inch PVC piping. The specimens were mounted in a biaxial servo-hydraulic materials testing machine (858 Bionix II, MTS Corporation, Eden Prairie, MN, USA) retrofitted with 2 spine gimbals and a passive XZ table. Custom-made rigid body markers comprised of three infrared light emitting diodes affixed between 2 small aluminum plates were placed on each vertebral body and the 2 gimbals to track the segmental motions. Nondestructive flexibility tests were performed about each axis of rotation (i.e., flexion-extension, right-left lateral bending, and right-left axial rotation) by applying an isolated ±0.27 Nm (0 Nm, 0.09 Nm, 0.18 Nm, and 0.27 Nm) moment about each of the primary axes. Each test initiated and concluded in the neutral position with zero load. Three loading and unloading cycles were performed with motion data collected on the third cycle (the first two cycles served as preconditioning). The displacement of each vertebrae was measured using an optoelectronic motion capture system (Optotrak, Northern Digital, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada); the output of which was synchronized with that of the MTS. During testing the specimens were kept moist with saline solution spray. Stiffness was determined and compared to normal controls (10 normal rabbit lumbar columns, historic internal laboratory controls).

Histology

Fusion sites of each animal were processed for histology and sectioned in the sagittal plane to obtain a total of 6 sections per animal (3 per side of the fusion mass). For each side, sections were created adjacent to the vertebral body, through the center of the fusion mass, and through the lateral aspect of the fusion mass, spaced approximately 3-mm apart. Sections were stained with H&E. All 6 sections from each fusion mass (3 per side) were subject to scoring based on a standard protocol.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed on the μCT and histomorphometry data, as well as the flexion-extension, lateral bending and axial rotation data from the flexibility analysis. All data was analyzed to a 95% confidence level (p<0.05) using a 2-tailed t-test assuming unequal variance in Microsoft Excel. Unless otherwise noted, data is reported as the mean and one standard deviation.

Results

Radiographs at 4, 8 and 12 weeks showed a normal healing response over time with no adverse reactions for all test groups. The loss of graft distinction at the host bone margins indicates a progression in host integration, implant remodeling and new bone formation over time. No fractures, osteolysis, or other adverse reactions were evident during radiographic examination for all test groups. Graft position migration from immediate postoperative radiographs to radiographs greater than 1-week post-operation is typically observed as the forces of overlaying muscle compresses the graft. These migration observations are typical of synthetic bone grafts applied in this animal model and are not a confounding variable.

Radiographs of the fusion masses were evaluated for new bone formation and implant resorption. The radiographic scoring shows an increase in new bone formation and implant resorption from 4 to 12 weeks for all test groups.

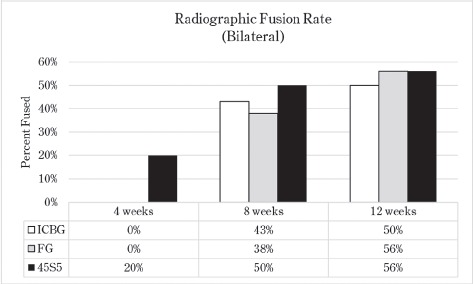

The radiographic fusion analysis is summarized in Figure 1. Fusion rates for ICBG and FG test groups were: ICBG 0%, FG 0%, and 45S5 20% at 4 weeks; ICBG 43%, FG 38%, and 45S5 50% at 8 weeks; and ICBG 50%, FG 56%, and 45S5 56% at 12 weeks (p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Radiographic Bilateral Fusion Analysis Summary. An increase in fusion rates at early time interval indicates that the presence of 45S5 in the graft tends to accelerate fusion kinetics.

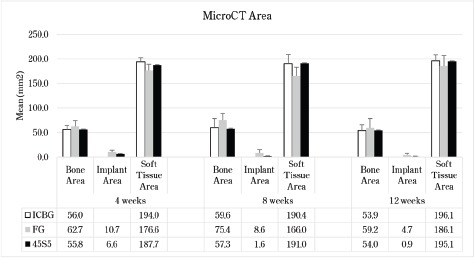

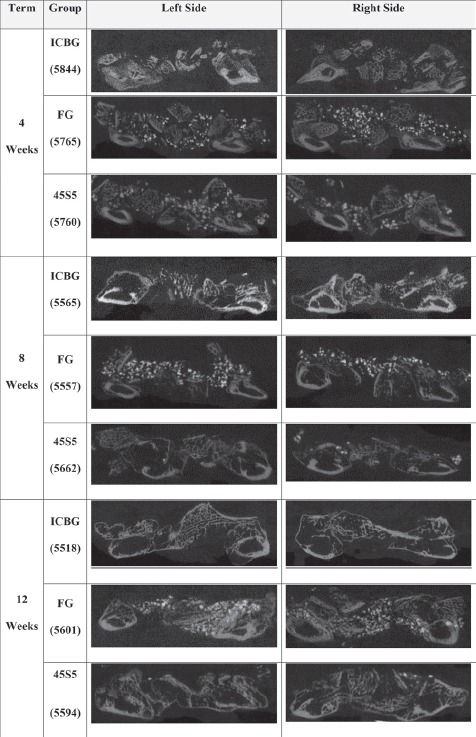

The μCT scans supported radiographic findings, showing a normal osteoconductive healing response over time with no adverse reactions for all test groups. The 4-weeks μCT scans showed host integration and new bone formation originating from the TP margins in all animals. The 8- and 12-weeks scans showed a progression of new bone formation and graft remodeling across the paraspinal bed from the 4-week time point. (Figures 2 and 3, and Table 1).

Figure 2.

μCT Mean Areas of Bone, Implant, and Soft Tissue with Standard Deviations. Both ICBG and 45S5 fusion masses show earlier signs of graft remodeling with more lamellar bone and stiffer fusion masses compared to FG fusions.

Figure 3.

Representative μCT Scans From Each Test Group and Time Point. The scans confirm that the 45S5 used as an extender leads to an healing outcome that closely resembles that of the ICBG.

Table I.

μCT Statistical Analysis (T-Test: 2-Tailed, Unequal Variance). The analysis demonstrates that the fusion kinetics of the 45S5 animal group match closely that of the ICBG group.

| Test Group | Bone Area | Implant Area | Soft Tissue Area | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 Weeks | FG | 45S5 | FG | 45S5 | FG | 45S5 |

| ICBG | 0.200 | 0.971 | N/A | N/A | 0.006 | 0.325 |

| FG | - | 0.339 | - | 0.054 | - | 0.140 |

| 8 Weeks | FG | 45S5 | FG | 45S5 | FG | 45S5 |

| ICBG | 0.045 | 0.747 | N/A | N/A | 0.007 | 0.930 |

| FG | - | 0.004 | - | 0.007 | - | 0.002 |

| 12 Weeks | FG | 45S5 | FG | 45S5 | FG | 45S5 |

| ICBG | 0.472 | 0.992 | N/A | N/A | 0.216 | 0.869 |

| FG | - | 0.487 | - | 0.003 | - | 0.272 |

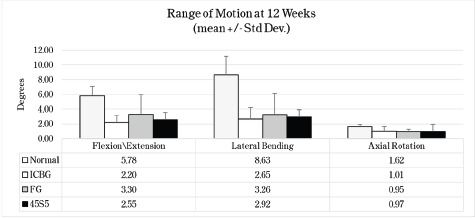

Spine fusion was assessed by manual palpation of the treated motion segments. At 4 weeks, only one 45S5 rabbit was graded as fused. At 8 weeks, 43% of the ICBG, 38% FG and 50% of 45S5 spine were fused mechanically. At 12 weeks, ICBG spine was fused 50%, FG 56%, and 45S 56%. General findings from the biomechanics indicate that the 3 groups had significantly less motion than the not-fused normal (Figure 4). There was no significant difference between the ICBG and the two test articles (FG and 45S5) specimens (Table 2).

Figure 4:

Mean Maximum Motion at 0.27 Nm with Standard Deviation. * Normal data baseline obtained from historical internal laboratory data of normal not-fused rabbits.

Table II.

Flexibility Testing Statistical Analysis (t-test: 2-tailed, unequal variance)

| p-values | ICBG | FG | 45S5 |

| Flexion/Extension | |||

| Normal (Not fused) | 0.0000 | 0.0266 | 0.0017 |

| ICBG | 0.2669 | 0.6550 | |

| FG | 0.2669 | 0.5200 | |

| 45S5 | 0.6550 | 0.5200 | |

| Lateral Bending | |||

| Normal (Not fused) | 0.0000 | 0.0006 | 0.0001 |

| ICBG | 0.5824 | 0.7761 | |

| FG | 0.5824 | 0.7906 | |

| 45S5 | 0.7761 | 0.7906 | |

| Axial Rotation | |||

| Normal (Not fused) | 0.0184 | 0.0003 | 0.0124 |

| ICBG | 0.8101 | 0.9003 | |

| FG | 0.8101 | 0.9315 | |

| 45S5 | 0.9003 | 0.9315 | |

Histopathology analysis of the fusion masses, from each test article and time point, indicated an expected normal response for resorbable calcium phosphate (HA/ TCP) and collagen graft material. The majority of specimens, regardless of implant type or time of implantation, had mild inflammation. Most often there were very low numbers of macrophages and multinucleated giant cells with some scattered, often lymphocytes and plasma cells. In all sections there is moderate neovascularization and fibrosis. Graft resorption and new bone formation increased with time from 4 to 12 weeks. Ultimately, there was no difference in histiologic response between groups.

Discussion

The objective of this study is to quantify the effect on fusion rate of 45S5 bioactive glass combined with an HA-TCP-collagen matrix by comparing the in vivo performance of 2 bone void filler materials, Bi-Ostetic bioactive glass foam (45S5) and Formagraft (FG), in an established posterolateral spine fusion rabbit model using ICBG as a control.

The test groups were evaluated for spine fusion rate, new bone formation, graft resorption and inflammatory response using radiographic, μCT, biomechanical and histological endpoints at 4, 8 and 12 weeks following implantation.

Radiographic scoring of the fusion sites indicated a normal healing response in all test groups, with no adverse reactions and similar progressions of new bone formation observed over time. Fusion rates for ICBG and FG test groups were: ICBG 0%, FG 0%, and 45S5 20% at 4 weeks; ICBG 43%, FG 38%, and 45S5 50% at 8 weeks; and ICBG 50%, FG 56%, and 45S5 56% at 12 weeks. μCT scans supported the radiographic observations, showing a normal osteoconductive healing response in all groups with remodeling of the fusion site over time.

Histopathology analysis of the fusion masses, from each test article and time point, indicated an expected normal response for resorbable HA, TCP and collagen graft materials. Mild inflammation with macrophage and multinucleated giant cell response to the graft material was evident in all test groups. Similar to μCT analysis, residual graft resorption and new bone formation increased over time. Both the ICBG and 45S5 fusion masses showed earlier signs of graft remodeling with more lamellar bone and stiffer fusion masses compared to the FG fusions.

The results of this study suggest that Bi-Ostetic bioactive glass foam is safe and effective in producing posterolateral fusion when employed as a bone graft extender. Some of the limitations of this study include the use of this rabbit animal model. Animal models cannot be directly translated to clinical application, and direct application of the test material in a clinical setting is appropriate. Additionally, with the growing cost concerns in medicine and spine care, surgeons and hospitals should assess the short- and long-term cost-effectiveness of implantable products like the bone graft substitutes and extenders.

Conclusion

This study has confirmed the biocompatibility, safety, efficacy and bone healing characteristics of the HA-TCP collagen (with or without 45S5 bioactive glass) composites. The results show that the 3 test groups had equivalent long-term fusion performance and outcome at 12 weeks. However, the presence of 45S5 bioactive glass seemed to accelerate the fusion process as evidenced by the higher fusion rates at 4 and 8 weeks for the HA-TCP-collagen composite containing bioactive glass particles. The results also demonstrate that the HA-TCP-45S5 bioactive glass-collagen composite used as an extender closely mirrors the healing characteristics (i.e. amount and quality of bone) of the 100% autograft group.

References

- 1.Arrington ED, Smith WJ, Chambers HG, Bucknell AL, Davino NA. Complications of iliac crest bone graft harvesting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;329:300–9. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebraheim NA, Elgafy H, Xu R. Bone-graft harvesting from iliac and fibular donor sites: techniques and complications. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9(3):210–8. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200105000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu RW, Bohlman HH. Fracture at the iliac bone graft harvest site after fusion of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;309:208–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahn B. Superior gluteal artery laceration, a complication of iliac bone graft surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;140:204–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurz LT, Garfin SR, Booth RE., Jr. Harvesting autogenous iliac bone grafts. A review of complications and techniques Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989;14(12):1324–31. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim EV, Lavadia WT, Roberts JM. Superior gluteal artery injury during iliac bone grafting for spinal fusion. A case report and literature review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21(20):2376–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199610150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasso RC, Williams JI, Dimasi N, Meyer PR., Jr. Postoperative drains at the donor sites of iliac-crest bone grafts. A prospective, randomized study of morbidity at the donor site in patients who had a traumatic injury of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(5):631–5. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199805000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silber JS, Anderson DG, Daffner SD, Brislin BT, Leland JM, Hilibrand AS, Vaccaro AR, Albert TJ. Donor site morbidity after anterior iliac crest bone harvest for single-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28(2):134–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200301150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.St John TA, Vaccaro AR, Sah AP, Schaefer M, Berta SC, Albert T, Hilibrand A. Physical and monetary costs associated with autogenous bone graft harvesting. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2003;32(1):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Summers BN, Eisenstein SM. Donor site pain from the ilium. A complication of lumbar spine fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71(4):677–80. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B4.2768321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu R, Ebraheim NA, Yeasting RA, Jackson WT. Anatomic considerations for posterior iliac bone harvesting. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21(9):1017–20. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199605010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiroff RT, White EW, Weber KN, Roy DM. Tissue ingrowth of Replamineform implants. J Biomed Mater Res. 1975;9(4):29–45. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820090407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boden SD, Kang J, Sandhu H, Heller JG. Use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 to achieve posterolateral lumbar spine fusion in humans: a prospective, randomized clinical pilot trial: 2002 Volvo Award in clinical studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27(23):2662–73. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen WJ, Tsai TT, Chen LH, Niu CC, Lai PL, Fu TS, McCarthy K. The fusion rate of calcium sulfate with local autograft bone compared with autologous iliac bone graft for instrumented short-segment spinal fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30(20):2293–7. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000182087.35335.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie Y, Chopin D, Morin C, Hardouin P, Zhu Z, Tang J, Lu J. Evaluation of the osteogenesis and biodegradation of porous biphasic ceramic in the human spine. Biomaterials. 2006;27(13):2761–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korovessis P, Repanti M, Koureas G. Does coralline hydroxyapatite conduct fusion in instrumented posterior spine fusion? Stud Health Technol Inform. 2002;91:109–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boden SD, Schimandle JH, Hutton WC. An experimental lumbar intertransverse process spinal fusion model. Radiographic, histologic, and biomechanical healing characteristics. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20(4):412–20. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199502001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schimandle JH, Boden SD. Spine update. The use of animal models to study spinal fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19(17):1998–2006. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199409000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]