Abstract

Background

Development and progression of myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) in dogs are difficult to predict. Identification at a young age of dogs at high risk of adverse outcome in the future is desirable.

Hypothesis/Objectives

To study the predictive value of selected clinical and echocardiographic characteristics associated with MMVD obtained at a young age for prediction of long‐term cardiac and all‐cause mortality in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCS).

Animals

1125 privately owned CKCS.

Methods

A retrospective study including CKCS examined at the age of 1–3 years. Long‐term outcome was assessed by telephone interview with owners. The value of variables for predicting mortality was investigated by Cox proportional hazard and Kaplan‐Meier analyses.

Results

Presence of moderate to severe mitral regurgitation (MR) (hazard ratio (HR) = 3.03, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) = 1.48–6.23, P = 0.0025) even intermittent moderate to severe MR (HR = 2.23, 95% CI = 1.48–6.23, P = 0.039) on color flow Doppler echocardiography was significantly associated with increased hazard of cardiac death. An interaction between MR and sex was significant for all‐cause mortality (P = 0.035), showing that males with moderate to severe MR had a higher all‐cause mortality compared to males with no MR (HR = 2.38, 95% CI = 1.27–4.49, P = 0.0071), whereas no difference was found between female MR groups. The risk of cardiac (HR = 1.37, 95% CI = 1.14–1.63, P < 0.001) and all‐cause (HR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.02–1.24, P = 0.016) mortality increased with increasing left ventricular end‐systolic internal dimension normalized for body weight (LVIDSN).

Conclusions and clinical importance

Moderate to severe MR, even if intermittent, and increased LVIDSN in dogs <3 years of age were associated with cardiac death later in life in CKCS.

Keywords: Dog, Heart failure, Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease, Risk factor

Abbreviations

- BW

body weight

- CHF

congestive heart failure

- CI

confidence interval

- CKCS

Cavalier King Charles Spaniel

- CV

coefficient of variation

- FS

fractional shortening

- h/R

diastolic LV posterior wall thickness relative to LV internal diastolic radius

- HR

hazard ratio

- LA/Ao

left atrial‐to‐aortic root ratio

- LVIDD

left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter

- LVIDDN

left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter normalized for BW

- LVIDS

left ventricular end‐systolic diameter

- LVIDSN

left ventricular end‐systolic diameter normalized for BW

- LV

left ventricular

- LVPWD

left ventricular free wall thickness in diastole

- MMVD

myxomatous mitral valve disease

- MR

mitral regurgitation

- MVP

mitral valve prolapse

Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) is the most common cardiovascular disease in dogs with a preponderance of middle‐ to old‐aged, small‐breed, male dogs.1, 2 MMVD is often regarded as a relatively benign condition.3 However, in some dogs, the disease will progress and cause congestive heart failure (CHF) due to long‐standing left ventricular and left atrial volume overload.3 Particularly, in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS), MMVD is associated with earlier onset and thus with potentially greater cardiac morbidity and mortality compared to other breeds.4, 5, 6 Yet, the preclinical period often varies markedly between dogs making it challenging for clinicians to identify dogs that will eventually succumb as a consequence of the disease.3, 7 Identification of this subpopulation of dogs at high risk of developing CHF, preferably at an early age, would have a number of advantages such as more targeted monitoring, and owner education on recognition of clinical signs. As studies indicate an inherited component to the disease in at least some of the highly susceptible breeds, early predictors would also allow for improved breeding recommendations.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 In addition, unnecessary owner concern of short lifespan might be avoided for low‐risk dogs.3 Thus, it is of great interest to identify risk factors and prognostic indicators associated with development, progression, and survival of dogs with MMVD. Previously studies have proposed a number of clinical and echocardiographic risk factors and prognostic indicators affecting survival.2, 13, 14, 15 However, many of these studies have been focusing on dogs at advanced stages of MMVD and it has been found that many of the echocardiographic variables do not change radically until late stages of MMVD.16 Thus, information about risk factors and prognostic indicators at an early age is sparse.

The aim of the study was to investigate the predictive value of selected clinical and echocardiographic characteristics associated with MMVD for prediction of long‐term cardiac and all‐cause mortality in CKCS before the age of 3 years.

Materials and Methods

The medical records of all client‐owned CKCS presented for echocardiographic evaluation at the Department of Veterinary Disease Biology, University of Copenhagen, between January 1, 1996, and June 30, 2012, were reviewed retrospectively.

Dogs between 1 and 3 years of age were evaluated for prebreeding cardiac screening, cardiac health check, or participation in previous cross‐sectional research projects. All owners provided written or oral informed consent.

All dogs underwent owner interview, clinical examination, standardized echocardiographic examination, and electrocardiography (ECG). The following clinical data were recorded: sex, age, coat color, date of birth, body weight (BW), presence, and grade of heart murmur. None of the dogs were sedated and owners were present during the entire examination. Based on auscultation, mitral regurgitation murmur intensity was graded 1–6.17 Intermittent murmurs and physiological flow murmurs (diagnosed as systolic murmurs with crescendo‐decrescendo sound configuration, point of maximal intensity at the left heart base, and mild or no concurrent MR found by color flow Doppler echocardiography18) were registered.

Echocardiography and Electrocardiography

Standardized transthoracic echocardiography with continuous ECG monitoring from parasternal and apical windows19 including 2D, M‐mode, and color flow Doppler was performed on all dogs. All examinations were performed by 2 experienced echocardiographers. Commercially available ultrasound units1 and transducers were used. If more than 1 echocardiographic examination had been conducted before the age of 3, the most recent examination was used for this study. Recorded echocardiograms were analyzed off‐line in a random order blinded for outcome of the dogs by 1 observer (MJR) either digitally2 or from videotape recordings transferred to digital files. Images of inadequate quality were excluded. The observer was blinded to all clinical data except date of birth of the dog during analysis of echocardiograms. In randomly selected dogs, measurements were repeated by the same observer (6 times; n = 6 dogs) and by a second observer (LHO) (n = 30). Severity of MR was assessed on color flow Doppler recordings from left apical four‐chamber view and classified as no (0%), mild (<20%), moderate (20–50%), severe (>50%), or intermittent based on maximal systolic regurgitant jet area relative to left atrial area.20 Intermittent MR was defined as no or mild MR in the majority of cardiac systoles but with some MR jets ≥20%.20 The degree of mitral valve prolapse (MVP) was evaluated from the right parasternal long‐axis four‐chamber view and graded: none (≤1 mm total MVP sum of anterior leaflet, posterior leaflet, and coaptation point protrusion into LA in systole according to annulus plane in increments of 1 mm), mild (2–4 mm), moderate (5–7 mm), or severe (≥8 mm).20, 21 Left atrial‐to‐aortic root ratio (LA/Ao) was assessed from right parasternal short‐axis view measured at first frame after closure of the aortic valve at the level of the aortic root as previously described.22 Left ventricular (LV) dimensions were measured from the right parasternal short‐axis view using M‐mode at the level of the chordae tendineae19: LV end‐diastolic and end‐systolic internal dimensions (LVIDD, LVIDS) and LV posterior wall thickness end‐diastolic dimension (LVPWD). Left ventricular internal dimensions were normalized to body weight (BW)23 and fractional shortening (FS) was calculated.24 The h/R ratio representing diastolic LV posterior wall thickness (h = LVPWD) relative to LV internal diastolic radius (R = LVIDD/2) was calculated as described elsewhere.25 All quantitative echocardiographic variables were based on mean of 3 measurements. Heart rate was recorded from a separate ECG paper recording that was performed after the initial part of the echocardiographic examination with the dog in right lateral recumbency by counting number of R–R intervals per 15 seconds.

Follow‐Up

Standardized telephone interviews were conducted between December 1, 2012, and June 30, 2013, with dog owners to determine the current health status of each dog. Dogs between 1 and 3 years that had been echocardiographically examined at the Department of Veterinary Disease Biology, University of Copenhagen, within the last year (between June 30, 2012, and June 30, 2013) were not included as health status was considered the same as at the last examination. Likewise, owners of older dogs that had been re‐examined at the Department of Veterinary Disease Biology, University of Copenhagen, within the last year were not contacted, but instead information from the medical records was used as health status was considered the same as at their last examination. A questionnaire with a number of predefined possible answers modified from Borgarelli et al.3, 15 was used. The interviewer was blinded to the clinical status of the dog at the initial examination. The owner was asked whether the dog was dead or alive. If the dog was dead, the owner was asked at what age death had occurred, whether the dog had been euthanized or died spontaneously, cause of death/reason for euthanasia, whether the dog had received cardiac treatment (including period of time receiving cardiac treatment and clinical effect), and whether the dog had clinical signs of CHF (including dyspnoea, breathlessness, nocturnal restlessness, frequent coughing, exercise intolerance, and syncope). Dogs were then allocated into the following groups depending on presumed cause of death: cardiac death or noncardiac death. Cardiac death was defined as death or euthanasia due to clinical signs of CHF or diagnosis of CHF by local veterinarian with or without diagnostics and response to cardiac treatment, sudden death with no other evident cause, death in anesthesia with previous cardiac signs, or euthanasia by authors due to refractory CHF. Sudden death was defined as death occurring within 1 hour after onset of clinical signs or a dog found dead by owner when arriving home. All other deaths were recorded as noncardiac‐related.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical software3 was used for data analysis and a P value of <0.05 was considered significant unless otherwise stated.

For descriptive statistics, dogs were divided into 4 groups: those that were alive, those dead due to heart disease, those dead due to other causes, and those that were lost to follow‐up. Data are reported as medians and interquartile ranges.

By Cox proportional hazard analysis, the effects on survival of the following variables were evaluated: sex, body weight (BW), coat color, MR group, MVP group, murmur, heart rate, LA/Ao, LVIDD normalized for BW (LVIDDN), LVIDS normalized for BW (LVIDSN), LVPWD, FS, and h/R. Age was used as timescale with entry at 3 years of age (delayed entry), ensuring that all dogs have the measurements performed. Dogs that were alive at the end of the study period were right‐censored. For the purpose of statistical analysis, the following groups were combined due to low numbers: MR groups moderate (n = 118) and severe (n = 8) to group MR moderate‐severe, MVP groups moderate (n = 183) and severe (n = 10) to group MVP 2, and finally murmur groups 1 (n = 23), intermittent 1 (n = 5), 2 (n = 19), and 3–6 (n = 0) to group murmur >0. The primary endpoints of the study were death and analyses were performed for all‐cause and cardiac death. Dogs dying from a combination of 2 or more causes (including a cardiac related cause) (n = 14) are listed as “combined” and thus are not included in statistical analysis as cardiac deaths.

Because the study was performed over several years, a period variable with 3 categories (1996–2001, 2002–2007, and 2008–2012) indicating the date of echocardiography was constructed. All significant variables in the 2 Cox proportional hazard analyses (the 1 for all‐cause and the 1 for cardiac death) were tested for interactions with the period variable, but none were found.

For descriptive purposes, univariate Cox proportional hazard analyses were performed. The primary analyses was multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses including relevant interactions (sex*MR group, sex*MVP group, and sex*murmur group). A combination of forward inclusion and backward elimination was applied to form a final model. The proportional hazards assumption as well as the assumption of log‐linear effect of continuous explanatory variables was investigated using cumulative martingale residuals.26

By the Kaplan‐Meier method, survival curves and median survival times with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated for all‐cause mortality.

The obtained multivariate Cox proportional hazard model for cardiac death was used to construct cumulative incidence curves for different combinations of MR and sex and all other variables that proved significant for mortality in the multivariable analyses set at their median values.

Differences between all variables for follow‐up dogs and dogs lost to follow‐up were tested by logistic regression using the variable lost to follow‐up (yes/no) as response variable (see Table S1).

Inter‐ and intraobserver variability coefficients of variation are also included in Table S2.

Results

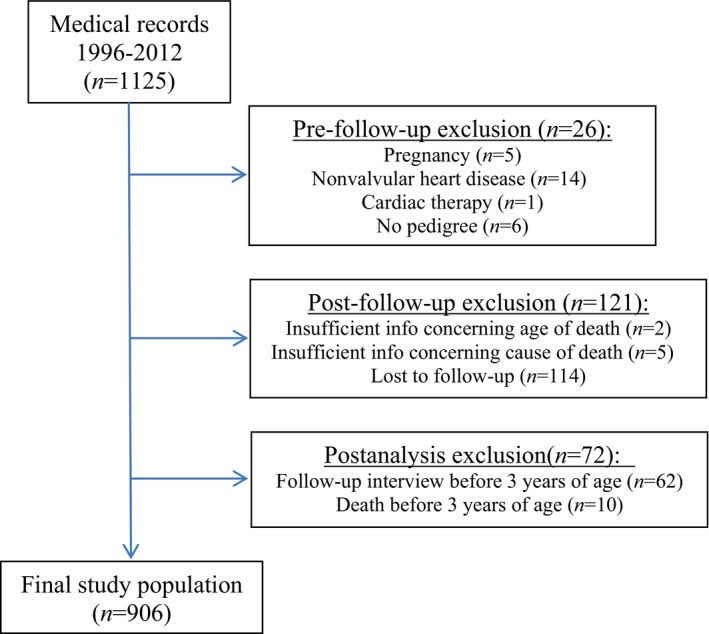

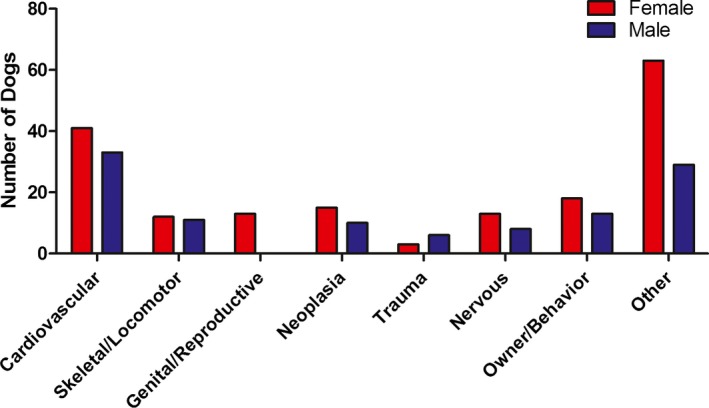

The study population included a total of 1125 CKCS. Figure 1 illustrates the exclusion of dogs. Baseline characteristics and echocardiographic values of the final study population are listed in Table 1. Of the 906 CKCS that had their status recorded, 288 died or were euthanized during the follow‐up period. Of these 74 (26%) were considered cardiac deaths. Of the 74 cardiac deaths, 31 (42%) died a sudden death (15 males and 16 females). There were 214 (74%) CKCS that died/were euthanized due to noncardiac causes. The median period of follow‐up was 3.1 years (quartile 1‐quartile 3, 1.5–5.4). Figures 2 and S1 show the different causes of death in males and females.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating reasons for exclusion of study dogs.

Table 1.

Dog characteristics and conventional echocardiographic variables for 1020 CKCS allocated according outcome in 2013

| Variable | n | Alive (1) | Cardiac death (2) | Non‐cardiac death (3) | Lost to follow‐up (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of CKCS | 1020 | 618 | 74 | 214 | 114 |

| Age at examination (days) | 1020 | 640 (571;749) | 745 (603;914) | 726 (597;863) | 650 (563;844) |

| Sex (f/m) | 1020 | 404/214 | 41/33 | 137/77 | 72/42 |

| Color (bh, bt, rb, tri) | 1020 | 217/146/124/131 | 30/11/10/23 | 84/31/33/66 | 42/17/23/32 |

| BW (kg) | 1020 | 8.2 (7.3;8.3) | 8.4 (7.4;9.6) | 8.2 (7.4;9.3) | 8.4 (7.2;9.6) |

| MR (no/mild/mod‐se/int) | 1015 | 282/200/63/72 | 15/27/16/14 | 70/83/23/36 | 41/38/24/11 |

| MVP (0/1/2) | 1017 | 68/430/119 | 16/42/16 | 26/155/32 | 9/78/26 |

| Murmur (0/>0/f) | 1020 | 570/11/37 | 57/11/6 | 164/18/32 | 92/7/15 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 968 | 120 (102;144) | 120 (102;132) | 114 (102;132) | 120 (102;141) |

| LA/Ao | 1002 | 1.2 (1.1;1.3) | 1.2 (1.1;1.2) | 1.2 (1.1;1.2) | 1.1 (1.0;1.2) |

| LVIDDN | 1015 | 1.5 (1.4;1.5) | 1.4 (1.3;1.5) | 1.4 (1.3;1.5) | 1.4 (1.3;1.5) |

| LVIDSN | 1015 | 0.9 (0.9;1.0) | 1.0 (0.9;1.0) | 0.9 (0.8;1.0) | 0.9 (0.8;1.0) |

| LVPWD | 1015 | 0.7 (0.6;0.8) | 0.7 (0.6;0.8) | 0.7 (0.6;0.8) | 0.7 (0.6;0.8) |

| FS (%) | 1015 | 32.7 (28.6;36.3) | 30.6 (27.6;36.0) | 32.4 (28.3;37.1) | 32.4 (28.0;37.7) |

| h/R | 1015 | 0.5 (0.5;0.6) | 0.5 (0.5;0.6) | 0.5 (0.5;0.6) | 0.5 (0.5;0.6) |

BW, body weight; CKCS, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels; color, coat color where bh, blenheim; bt, black and tan; rb, ruby, tri, tricolor; FS, fractional shortening; h/R, LV posterior wall thickness relative to internal diastolic radius; LA/Ao, ratio of left atrium to aortic root; LVIDDN, left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter normalized for BW; LVIDSN, left ventricular end‐systolic diameter normalized for BW; LVPWD, left ventricular free wall thickness in diastole; MR, mitral regurgitation group where no = no (0%), mild, mild (<20%), mod‐se, moderate‐severe (20–100%), int, intermittent (most often mild MR but some MR jets ≥ 20%); MVP, mitral valve prolapse group where 0 = ≤1 mm total MVP, 1 = 2‐4 mm total MVP, 2 = ≥5 mm total MVP; murmur, mitral regurgitation murmur intensity group where 0 = no murmur, >0 = murmur 1–6, f = flow murmur. Values reported are median and interquartile ranges.

Figure 2.

Histogram showing causes of death in the 288 CKCS. Other includes: old age (males = 2; females = 9), toxic (males = 1; females = 3), endocrinology (males = 2; females = 0), gastrointestinal (males = 3; females = 1), unspecified (males = 2; females = 7), anesthesia without previous cardiac clinical signs (males = 0; females = 3), ocular (males = 4; females = 3), immune‐mediated (males = 0; females = 4), auditory and integument (males = 2; females = 1), respiratory (males = 1; females = 1), kidney/liver/pancreas (males = 2; females = 10), iatrogen (males = 1; females = 0), combination of 2 or more categories including cardiovascular (males = 5; females = 9), combination of 2 or more categories excluding cardiovascular (males = 4; females = 12).

Survival Analyses

Table 2 shows univariable predictors of all‐cause mortality and cardiac death.

Table 2.

Results of univariable Cox proportional hazard analyses of factors predictive for survival (all‐cause and cardiac mortality) in 906 CKCS

| All‐Cause Mortality | Cardiac Death | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/Number of Events | HR (95% CI) | P | n/Number of Events | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| MR group | 901/284 | 901/72 | ||||

| mild vs. no | 0.95 (0.72;1.27) | 0.75 | 1.30 (0.69;2.44) | 0.42 | ||

| mod‐se vs. no | 1.25 (0.86;1.83) | 0.24 | 2.81 (1.39;5.69) | 0.0041 | ||

| int vs. no | 1.11 (0.78;1.58) | 0.57 | 1.72 (0.83;3.56) | 0.15 | ||

| MVP | 904/287 | 904/74 | ||||

| 1 vs. 0 | 1.08 (0.77;1.51) | 0.66 | 0.60 (0.34;1.08) | 0.087 | ||

| 2 vs. 0 | 1.38 (0.91;2.12) | 0.13 | 1.20 (0.59;2.44) | 0.61 | ||

| Murmur | 906/288 | 906/74 | ||||

| >0 vs. 0 | 0.91 (0.61;1.35) | 0.63 | 1.27 (0.66;2.45) | 0.48 | ||

| f vs. 0 | 1.21 (0.86;1.71) | 0.28 | 0.69 (0.30;1.60) | 0.38 | ||

| Heart rate | 863/275 | 0.99 (0.99;1.00) | 0.021 | 863/71 | 1.00 (0.99;1.01) | 0.88 |

| Sex (males) | 906/288 | 1.15 (0.90;1.46) | 0.263 | 906/74 | 1.44 (0.91;2.27) | 0.12 |

| Color | 906/288 | 906/74 | ||||

| Bt vs. Bh | 0.86 (0.60;1.23) | 0.41 | 0.87 (0.44;1.74) | 0.70 | ||

| Rb vs. Bh | 0.99 (0.69;1.41) | 0.95 | 0.97 (0.47;1.98) | 0.93 | ||

| Tri vs. Bh | 1.16 (0.88;1.54) | 0.29 | 1.09 (0.63;1.88) | 0.76 | ||

| BW | 906/288 | 1.01 (0.94;1.09) | 0.80 | 906/74 | 1.02 (0.88;1.18) | 0.78 |

| LA/Ao | 894/285 | 0.36 (0.098;1.35) | 0.13 | 894/74 | 0.12 (0.0093;1.58) | 0.11 |

| LVIDDN | 901/285 | 1.03 (0.95;1.11) | 0.50 | 901/74 | 1.12 (0.96;1.29) | 0.14 |

| LVIDSN | 901/285 | 1.14 (1.04;1.25) | 0.0052 | 901/74 | 1.33 (1.12;1.57) | 0.0010 |

| LVPWD | 901/285 | 0.96 (0.86;1.08) | 0.51 | 901/74 | 0.88 (0.70;1.10) | 0.26 |

| FS | 901/285 | 0.96 (0.94;0.98) | <0.001 | 901/74 | 0.93 (0.90;0.97) | <0.001 |

| h/R | 901/285 | 0.76 (0.21;2.73) | 0.68 | 901/74 | 0.15 (0.011;2.01) | 0.15 |

BW, body weight; CKCS, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels; color, coat color where bh, blenheim; bt, black and tan; rb, ruby; tri, tricolor; FS, fractional shortening; h/R, LV posterior wall thickness relative to internal diastolic radius; LA/Ao, ratio of left atrium to aortic root; LVIDDN, left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter normalized for BW; LVIDSN, left ventricular end‐systolic diameter normalized for BW; LVPWDN, left ventricular free wall thickness in diastole normalized for BW; MR, mitral regurgitation group where no = no (0%), mild, mild (<20%), moderate‐se, moderate‐severe (20–100%), int, intermittent (most often mild MR but some MR jets ≥20%); MVP, mitral valve prolapse group where 0 = ≤1 mm total MVP, 1 = 2–4 mm total MVP, 2 = ≥5 mm total MVP; murmur, mitral regurgitation murmur intensity group where 0 = no murmur, >0 = murmur 1–6, f = flow murmur. Bold values are statistically significant.

Based on the results from univariable analysis, the following variables were considered for multivariable modeling: LVIDSN, LA/Ao, FS, heart rate, MR group, MVP group, and sex. Collinearity (Spearman's correlation of −0.59) was found between FS and LVIDSN. As LVIDSN was the best predictor concerning cardiac death, this variable was chosen for multivariate analysis. A statistically significant interaction between MR group and sex was found. All multivariable analyses (all‐cause and cardiac mortality) were performed including the explanatory variables: LVIDSN, LA/Ao, heart rate, MVP group, and the interaction between MR group and sex. When adjusting for the other explanatory variables, heart rate and MVP group were no longer significant for all‐cause or cardiac mortality, Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of multivariable Cox proportional hazard analyses of factors predictive of survival in 906 CKCS

| Variable | All‐cause mortality | Cardiac death | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| LVIDSN | 1.13 (1.02;1.24) | 0.016 | 1.37 (1.14;1.63) | <0.001 |

| LA/Ao | 0.17 (0.044;0.68) | 0.012 | 0.045 (0.0030;0.69) | 0.026 |

| MR*sex | – | 0.035 | – | 0.99 |

| MR group | – | – | 1.51 (0.78;2.90) | 0.22 |

| mild vs. no | 3.03 (1.48;6.23) | 0.0025 | ||

| mod‐se vs. no int vs. no | 2.23 (1.04;4.79) | 0.039 | ||

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LA/Ao, ratio of left atrium to aortic root; LVIDSN, left ventricular end‐systolic diameter normalized for BW; MR, mitral regurgitation group where no = no (0%), mild, mild (<20%), moderate‐se, moderate‐severe (20–100%); int, intermittent (most often mild MR but some MR jets ≥20%). Bold values are statistically significant.

A higher value of LVIDSN at examination between 1 and 3 years of age significantly increased the hazard of cardiac and all‐cause mortality. Dogs with moderate to severe MR and intermittent MR had significantly increased hazard of cardiac death compared to dogs with no MR. Counterintuitively, a lower value of LA/Ao at examination between 1 and 3 years of age significantly increased the hazard of cardiac and all‐cause mortality.

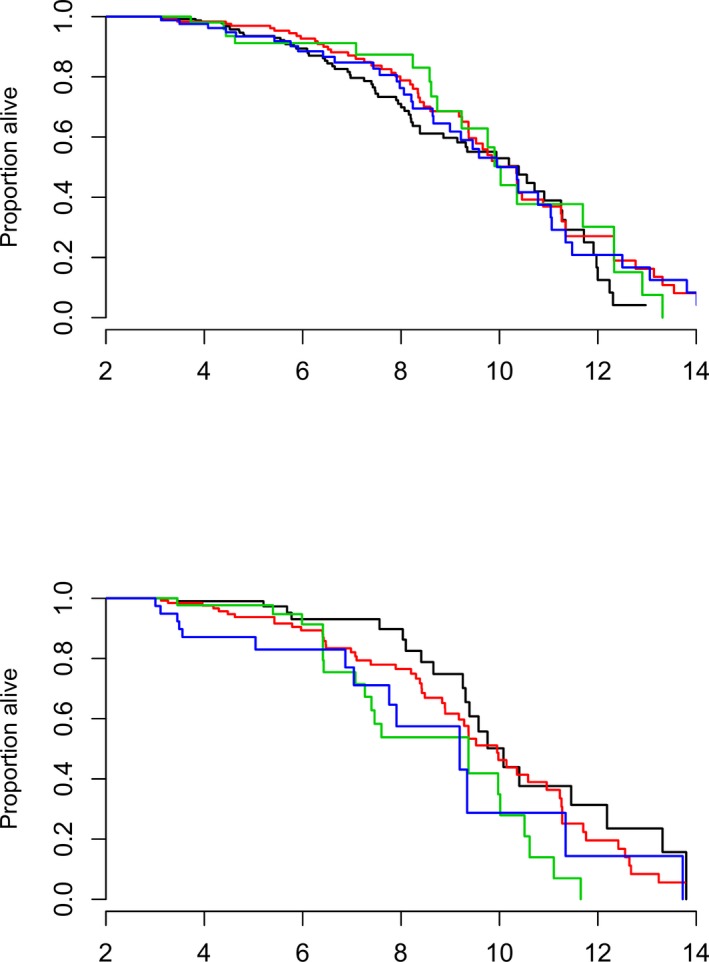

The interaction between MR group and sex was significant for all‐cause mortality but not cardiac death. Males with moderate to severe MR had significantly increased hazard ratio of death compared to males with no MR (hazard ratio = 2.38, 95% CI = 1.27–4.49, P = 0.0071) whereas there was no significant differences between MR groups for females, Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Kaplan‐Meier curves for all‐cause mortality given for each combination of sex (top = females, bottom = males) and mitral regurgitation (MR) group where black curve represents no MR = 0%, red curve represents mild MR (<20%), green curve represents moderate (20–50%)‐severe (>50%) MR, and blue curve represents intermittent MR (most often mild MR but some MR jets ≥20%).

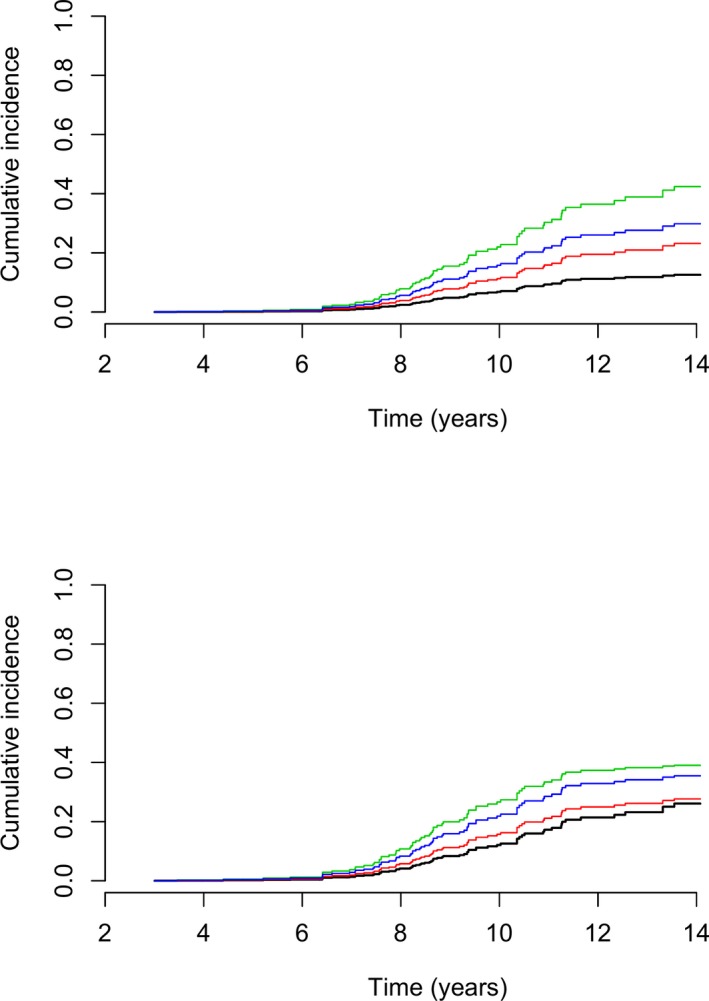

Figure 4 shows cumulative incidence curves for cardiac death, demonstrating that having moderate to severe MR at 1–3 years age or presence of intermittent MR is associated with increased risk of cardiac death.

Figure 4.

Cumulative incidence curves for cardiac death given for each combination of sex (top = females, bottom = males) and mitral regurgitation (MR) group where black curve represents no MR = 0%, red curve represents mild MR (<20%), green curve represents moderate (20–50%)‐severe (>50%) MR, and blue curve represents intermittent MR (most often mild MR but some MR jets ≥ 20%). The remaining variables are set at their median values (LVIDSN = 0.93, LA/Ao = 1.2, and HR = 120).

Discussion

The results of the present study show that presence of more than mild MR even if intermittent on echocardiography in CKCS aged 1–3 years was associated with increased risk of cardiac death. This was especially true for male dogs. Finally, even though MMVD generally is considered a relatively benign condition, a relatively large proportion (more than one‐fourth) of the CKCS deaths in the present study were due to cardiac causes.

To minimize variability, the present study followed a standardized protocol at the same research facility and only very few operators and observers were included. Furthermore, a large number of dogs were included and all dogs were of the same breed. Surprisingly, only few variables were predictive of mortality. Yet, this is probably in part due to the very young age at which the dogs were examined.

As expected, more severe MR at examination at young age was associated with increased cardiac mortality in CKCS. This was however not the case when MR was based on murmur intensity on auscultation underlining the importance of assessment of MR using cardiac ultrasound.15, 18 In accordance with the present study, previous studies evaluating murmur intensity also found limited prognostic significance of low‐grade murmurs.27, 28 In the present study, flow murmurs do not appear to have any prognostic significance either. There are a number of ongoing breeding programs aimed at decreasing the prevalence of MMVD in CKCS in several different countries.12, 29, 30 These programs are mostly based on identification of MR using auscultation but some also include echocardiography (estimating the degree of MVP) and parental information. A recent study concerning the Danish breeding program for CKCS based on auscultation and echocardiography did find a decrease in prevalence of MMVD; however, it was unclear whether auscultation, echocardiography (estimating the degree of MVP), or the fact that the program was mandatory contributed most to this effect.12 Yet, based on the results from the present study, it could seem that adding echocardiographic information estimating the degree of MR to the breeding evaluation might be useful. It is important to be aware of the fact that color flow Doppler echocardiography is a semiquantitative estimate influenced by factors such as echocardiographic equipment and technical settings.31 However, other methods of estimating MR size such as calculation of the effective regurgitant orifice area (EROA) using the proximal isovelocity surface area (PISA) or vena contracta are not always possible to achieve in mild cases of MR.

Interestingly, presence of echocardiographic intermittent MR was also associated with increased cardiac mortality. The nature of intermittent MR is generally poorly characterized and the clinical importance of this phenomenon has not previously been studied in dogs20 and has not been described in human patients. A surprising and interesting finding was that intermittent MR but not mild MR was associated with cardiac mortality, considering that the MR in intermittent MR was mild in most heart beats. A possible explanation might be that the single heart beats with more severe MR mediates valvular shear stress that influences disease progression or that the atrium cannot handle the more severe MRs that suddenly occur. A previous study found intermittent MR to be associated with variations in R–R interval.20 Thus, another hypothesis is that intermittent MR might represent moderate or severe MR masked by a variation in R–R interval or heart rate. These hypotheses would imply that intermittent MRs should be considered as serious as the maximal MR observed instead of the MR that is most often observed. Thus, intermittent MR or intermittent murmurs might be warning sign that warrant more close surveillance of a patient. It is unknown whether the size of the intermittent MR is important in relation to progression of MMVD, and whether intermittent MR is an early manifestation of progression to more advanced MR. Thus, further studies are needed to clarify the importance of this phenomenon.

The fact that MR group (as an interaction with sex) was also associated with all‐cause mortality may seem odd, but it probably is a consequence of the relationship between cardiac death and all‐cause mortality.

In dogs with MMVD, previous studies have suggested MVP to have prognostic significance.27, 28, 32 The fact that MVP was not associated with survival in the present study does not imply that MVP should not be used as an early risk factor for MMVD and cardiac death. As the vast majority of the CKCS had some degree of MVP, and relative few dogs had no or severe MVP, it can be difficult to show significant differences associated with MVP. Furthermore, in the present study, the consequences of MVP (which is MR) did have prognostic significance.

Higher LVIDSN (and lower FS) was associated with a higher all‐cause and cardiac mortality. This is an interesting finding. It may be hypothesized that this finding could indicate a systolic dysfunction at a very early age in CKCS. However, the clinical significance of the finding remains uncertain as the values of both LVIDSN and FS were generally within reference ranges of normal dogs13, 20, 33 Previous studies have found systolic LV dimensions to have predictive value for survival, but to the authors knowledge, this has not be evaluated previously in CKCS this young.3, 16, 25, 34 In human patients with MR, severe LV dilatation with increased chamber dimensions is associated with poor prognosis and considered important for timing of surgical intervention.35

Decreased LA/Ao ratio was also found to be associated with a higher all‐cause and cardiac mortality. This was not expected and counterintuitive as it is generally accepted that increasing LA/Ao is a risk factor in MMVD.3, 13, 15, 36 Again, it should be kept in mind that the dogs are very young and that all LA/Ao values were within a very narrow range and all within reference ranges of normal dogs37 and thus could represent a finding occurring at random.

Myxomatous mitral valve disease generally is considered a relatively benign condition. Yet, in the present study a relatively large proportion of the CKCS deaths were due to cardiac causes (26%). In the present study, life time could not be estimated as dogs were included at the age of 3, meaning that the life time would be overestimated as dogs dying before 3 years of age were excluded. However, data suggested (Fig 4) that cardiac mortality does not begin to increase before the age of 7 years and that many dogs survive longer than that. In addition, we found that dogs with moderate to severe MR even when intermittent had increased risk of death and that this was especially true for male dogs. This is in accordance with previous studies indicating that MMVD in male dogs is more common and progress faster.8, 9, 38 Further, data suggest (Fig 3) that males have a trend toward higher all‐cause mortality rate with approximately 60% of male CKCS dying before the age of 10 years compared to only approximately 50% of the females.

Generally, the dogs lost to follow‐up were dogs that changed owner. There were differences in few echocardiographic measurements between CKCS included in survival analysis and CKCS lost to follow‐up (see Table S1). This comparison was made to assess for selection bias. It is unclear how this may have influenced our findings.

Limitations of the study include selection bias as dogs were privately owned and chosen from a database of CKCS used primarily for breeding purposes. This is also the reason that more female CKCS were included compared to males.

Furthermore, due to the retrospective nature of the present study, it was challenging to classify cause of death (based primarily on owner statements) and a proportion of the deaths may have been inaccurately classified. Many dogs had died a long time ago and many owners had more than 1 dog, and thus, it may have been a problem for the owner to remember the actual circumstances. In addition, in the majority of the cases, the diagnosis was based on findings from the owners’ local veterinarian and often diagnoses were quite unspecific and/or based on only few diagnostic tests. Clinical signs are often difficult to differentiate from other conditions of elderly dogs and coughing and exercise intolerance may as well be a sign of bronchitis and osteoarthritis. Often the decision to euthanize a dog is multifactorial and the extent to which heart disease played a part is impossible to determine. In the present study, CKCS euthanized because of a combination of cardiac signs and other problems (n = 14) were assigned to a “combined causes” category and thus did not figure as cardiac deaths. Similarly, 2 dogs were euthanized because of a poor result at their prebreeding cardiac examination and these dogs were assigned to the “owner/behavior” category (see Fig 2). A number of CKCS were euthanized because of neurologic signs that the local veterinarian assigned to epilepsy, cerebral hemorrhage, or thrombosis. These signs could be misdiagnosed syncope or results of cardiac disease as thrombus formation is a known complication of heart disease. Therefore, it could be argued that these dogs should have been categorized as cardiac deaths. In contrast, other diseases than heart disease without previous clear signs might have resulted in sudden death (i.e, subclinical neoplasia or intracranial problems), thus causing overestimation of cardiac related death. In the present study, it was not possible to differentiate types of cardiac disease in this study, but given the high prevalence of MMVD in CKCS, it is assumed that the majority of cardiac deaths were due to MMVD.1, 4

An additional limitation is the effect of time that may have influenced results in several ways. All off‐line echocardiographic analyses were performed by a single observer. Furthermore, no interactions were found with the period variable and any of the significant variables in the Cox proportional hazard analyses. However, the operators performing auscultation and echocardiography (even though they were highly experienced) and echocardiographic equipment did change few times over time. This is especially of concern for color flow Doppler echocardiography which is a semiquantitative estimate influenced by a number of factors such as echocardiographic equipment, technical settings, flow direction, and blood pressure.31, 39

Estimation of MR by the jet area method with color flow Doppler echocardiography is not optimal. However, gold standard methods requiring anesthesia of the dog, for example, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging were not possible in the present study.

Differentiation between intermittent MR and mild MR can be very challenging because movement of the heart during systole might change the plane of scan, and thus, mild MRs can disappear from the plane of scan and appear to be intermittent. Various apical planes are therefore beneficial to grade MR. However, the recordings available in the present study did not permit for more planes to be included in the echocardiographic evaluation. Further prospective studies are needed to clarify the presence and significance of intermittent MR.

Finally, the different follow‐up times of the dogs caused by the study design and fact that an ongoing breeding program with documented effect12 was being carried out simultaneously may have influenced results.

Conclusions

The present study indicates that presence of moderate to severe MR, intermittent moderate to severe MR, and increased LV systolic dimensions at 1–3 years of age are associated with increased cardiac mortality in CKCS later in life. Flow murmurs and mild MR did not influence cardiac mortality.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Causes of death in 288 CKCS plotted according to age. Other includes: old age (males = 2; females = 9), toxic (males = 1; females = 3), endocrinology (males = 2; females = 0), gastrointestinal (males = 3; females = 1), unspecified (males = 2; females = 7), anesthesia without previous cardiac clinical signs (males = 0; females = 3), ocular (males = 4; females = 3), immune‐mediated (males = 0; females = 4), auditory and integument (males = 2; females = 1), respiratory (males = 1; females = 1), kidney/liver/pancreas (males = 2; females = 10), iatrogen (males = 1; females = 0), combination of 2 or more categories including cardiovascular (males = 5; females = 9), combination of 2 or more categories excluding cardiovascular (males = 4; females = 12). In 2 dogs the age of death was unknown.

Table S1. Statistically significant results of logistic regression analyses between follow‐up dogs and dogs lost to follow‐up.

Table S2. Inter‐ and intraobserver variability coefficients of variation of the echocardiographic variables.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Christina Tirsdal Kjempff at the Department of Veterinary Disease Biology and Dennis Jensen at the Department of Veterinary Clinical and Animal Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, for technical assistance.

Conflict of Interest Declaration

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Off‐label Antimicrobial Declaration

Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

This study was performed at the Department of Veterinary Disease Biology, University of Copenhagen.

The study was supported financially by a PhD study grant from the Novo Nordisk—LIFE In Vivo Pharmacology Centre (LIFEPHARM) and the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences and the Danish Council of Independent Research | Medical Sciences (Project no. 271‐08‐0998).

Preliminary results were presented orally at the 2016 European College of Veterinary Internal Medicine—Companion Animals (ECVIM‐CA) Forum, Goteborg, September 8‐10, 2016.

Notes

Aloka SSD‐2200 (January 1, 1996–December 31, 2000); Vivid 3 echocardiograph, GE‐medical, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA (January 1, 2001–July 15, 2008) and Vivid® i echocardiograph, GE‐medical, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA (July 16, 2008–July 30, 2013)

EchoPAC PC. Version 112, GE Vingmed Ultrasound AS, Horten, Norway.

R studio, version 0.97.336, © 2009–2012 RStudio, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts

References

- 1. Buchanan JW. Chronic valvular disease (Endocardiosis) in dogs. Adv Vet Sci Comp Med 1977;21:75–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haggstrom J, Hoglund K, Borgarelli M. An update on treatment and prognostic indicators in canine myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Small Anim Pract 2009;50:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Borgarelli M, Savarino P, Crosara S, et al. Survival characteristics and prognostic variables of dogs with mitral regurgitation attributable to myxomatous valve disease. J Vet Intern Med 2008;22:120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Egenvall A, Bonnett BN, Haggstrom J. Heart disease as a cause of death in insured Swedish dogs younger than 10 years of age. J Vet Intern Med 2006;20:894–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thrusfield MV, Aitken CGG, Darke PGG. Observations on breed and sex in relation to canine heart valve incompetence. J Small Anim Pract 1985;26:709–717. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Darke PG. Valvular incompetence in cavalier king Charles spaniels. Vet Rec 1987;120:365–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Atkins C, Bonagura J, Ettinger S, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of canine chronic valvular heart disease. J Vet Intern Med 2009;23:1142–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Swenson L, Haggstrom J, Kvart C, Juneja R. Relationship between parental cardiac status in cavalier king Charles spaniels and prevalence and severity of chronic valvular disease in offspring. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1996;208:2009–2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olsen LH, Fredholm M, Pedersen HD. Epidemiology and inheritance of mitral valve prolapse in dachshunds. J Vet Intern Med 1999;13:448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Madsen MB, Olsen LH, Haggstrom J, et al. Identification of 2 loci associated with development of myxomatous mitral valve disease in cavalier king Charles spaniels. J Hered 2011;102:S62–S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lewis T, Swift S, Woolliams JA, Blott S. Heritability of premature mitral valve disease in cavalier king Charles spaniels. Vet J 2011;188:73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Birkegard AC, Reimann MJ, Martinussen T, et al. Breeding restrictions decrease the prevalence of myxomatous mitral valve disease in cavalier king Charles spaniels over an 8‐ to 10‐year period. J Vet Intern Med 2016;30:63–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moonarmart W, Boswood A, Luis Fuentes V, et al. N‐terminal Pro B‐type natriuretic peptide and left ventricular diameter independently predict mortality in dogs with mitral valve disease. J Small Anim Pract 2010;51:84–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hezzell MJ, Boswood A, Moonarmart W, Elliott J. Selected echocardiographic variables change more rapidly in dogs that die from myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Vet Cardiol 2012;14:269–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Borgarelli M, Crosara S, Lamb K, et al. Survival characteristics and prognostic variables of dogs with preclinical chronic degenerative mitral valve disease attributable to myxomatous degeneration. J Vet Intern Med 2012;26:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lord P, Hansson K, Kvart C, Haggstrom J. Rate of change of heart size before congestive heart failure in dogs with mitral regurgitation. J Small Anim Pract 2010;51:210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gompf RE. The clinical approach to heart disease: History and physical examination In: Fox PR, ed. Canine and Feline Cardiology. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1988:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pedersen HD, Haggstrom J, Falk T, et al. Auscultation in mild mitral regurgitation in dogs: Observer variation, effects of physical maneuvers, and agreement with color Doppler echocardiography and phonocardiography. J Vet Intern Med 1999;13:56–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thomas WP, Gaber CE, Jacobs GJ, et al. Recommendations for standards in transthoracic two‐dimensional echocardiography in the dog and cat. Echocardiography committee of the specialty of cardiology, American college of veterinary internal medicine. J Vet Intern Med 1993;7:247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reimann MJ, Moller JE, Haggstrom J, et al. R–R interval variations influence the degree of mitral regurgitation in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease. Vet J 2014;199:348–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pedersen HD, Olsen LH, Mow T, Christensen NJ. Neuroendocrine changes in dachshunds with mitral valve prolapse examined under different study conditions. Res Vet Sci 1999;66:11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haggstrom J, Hansson K, Karlberg BE, et al. Plasma concentration of atrial natriuretic peptide in relation to severity of mitral regurgitation in cavalier king Charles spaniels. Am J Vet Res 1994;55:698–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cornell CC, Kittleson MD, Della Torre P, et al. Allometric scaling of M‐mode cardiac measurements in normal adult dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2004;18:311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lombard CW. Normal values of the canine M‐mode echocardiogram. Am J Vet Res 1984;45:2015–2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Borgarelli M, Tarducci A, Zanatta R, Haggstrom J. Decreased systolic function and inadequate hypertrophy in large and small breed dogs with chronic mitral valve insufficiency. J Vet Intern Med 2007;21:61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martinussen T, Scheike TH. Dynamic Regression Models for Survival Data, New York: Springer‐Verlag; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Olsen LH, Martinussen T, Pedersen HD. Early echocardiographic predictors of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dachshunds. Vet Rec 2003;152:293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pedersen HD, Lorentzen KA, Kristensen BO. Echocardiographic mitral valve prolapse in cavalier king Charles spaniels: Epidemiology and prognostic significance for regurgitation. Vet Rec 1999;144:315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Swift S, Cripps P. Results of the UK Cavalier King Charles Breeding Program: 1991–2000. Abstract in the proceeding of the annual meeting of ACVIM, Seattle, Washington, USA 2013.

- 30. Lundin T, Kvart C. Evaluation of the Swedish breeding program for cavalier king Charles spaniels. Acta Vet Scand 2010;52:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zoghbi W, Enriquez‐Sarano M, Foster E, et al. Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two‐dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2003;16:777–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sargent J, Muzzi R, Mukherjee R, et al. Echocardiographic predictors of survival in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Vet Cardiol 2015;17:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Misbach C, Lefebvre HP, Concordet D, et al. Echocardiography and conventional Doppler examination in clinically healthy adult cavalier king Charles spaniels: Effect of body weight, age, and gender, and establishment of reference intervals. J Vet Cardiol 2014;16:91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Haggstrom J, Boswood A, O'Grady M, et al. Effect of pimobendan Or benazepril hydrochloride on survival times in dogs with congestive heart failure caused by naturally occurring myxomatous mitral valve disease: The QUEST study. J Vet Intern Med 2008;22:1124–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carabello BA, Crawford FA Jr. Valvular heart disease. N Engl J Med 1997;337:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Reynolds CA, Brown DC, Rush JE, et al. Prediction of first onset of congestive heart failure in dogs with degenerative mitral valve disease: The PREDICT cohort study. J Vet Cardiol 2012;14:193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hansson K, Haggstrom J, Kvart C, Lord P. Left atrial to aortic root indices using two‐dimensional and m‐mode echocardiography in cavalier king Charles spaniels with and without left atrial enlargement. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2002;43:568–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Detweiler DK, Patterson DF. The prevalence and types of cardiovascular disease in dogs. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1965;127:481–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tou SP, Adin DB, Estrada AH. Echocardiographic estimation of systemic systolic blood pressure in dogs with mild mitral regurgitation. J Vet Intern Med 2006;20:1127–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Causes of death in 288 CKCS plotted according to age. Other includes: old age (males = 2; females = 9), toxic (males = 1; females = 3), endocrinology (males = 2; females = 0), gastrointestinal (males = 3; females = 1), unspecified (males = 2; females = 7), anesthesia without previous cardiac clinical signs (males = 0; females = 3), ocular (males = 4; females = 3), immune‐mediated (males = 0; females = 4), auditory and integument (males = 2; females = 1), respiratory (males = 1; females = 1), kidney/liver/pancreas (males = 2; females = 10), iatrogen (males = 1; females = 0), combination of 2 or more categories including cardiovascular (males = 5; females = 9), combination of 2 or more categories excluding cardiovascular (males = 4; females = 12). In 2 dogs the age of death was unknown.

Table S1. Statistically significant results of logistic regression analyses between follow‐up dogs and dogs lost to follow‐up.

Table S2. Inter‐ and intraobserver variability coefficients of variation of the echocardiographic variables.