Abstract

Aim:

The present study was aimed to highlight the current prescribing pattern of oral hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus and to evaluate the therapeutic effectiveness of these therapeutic categories in achieving target glycemic control.

Methods:

This is a prospective, cross-sectional, observational study of 6 months’ duration conducted in a tertiary care hospital of Lahore, Pakistan.

Results:

The current research recruited 145 patients presented in diabetes management center of a tertiary care hospital in Lahore, Pakistan. Mean age of the participants was 50.2 (± 8.5) years. Out of the 145 patients, 63% were females and 37% were males. Most patients were diagnosed to have diabetes within the past 5 years. Diabetes-induced neuropathy was the most common complication (71.7%) among the patients. A large proportion of these patients (70.3%) were also suffering from other comorbidities among which the most common one is hypertension. The average number of prescribed medications was 1.31. Metformin was prescribed to a majority of patients (64%) as monotherapy while 28.96% received combination therapy. Mean glycated hemoglobin (HBA1c) before and after 3 months of treatment was 8.5 (± 2.3) and 8.04 (± 2.1), respectively. Inferential statistics show a strong association between HBA1c and life style modifications and adherence to medication therapy (P = 0.05). However, the correlation between HBA1c and Morisky score and duration of disease was inverse and weak (P = 0.6, 0.4). The t-test values show a small difference between HBA1c values before and after 3 months (t = 0.440 and 0.466, respectively).

Conclusion:

Optimization of medication regimen and continuous patient education regarding life style modification and adherence to medication therapy are necessitated to bring HBA1c values near to target.

KEYWORDS: Diabetes mellitus, glycated hemoglobin, Lahore, Morisky score, Pakistan, prescribing trends

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder resulting from a decrease in insulin secretion and insulin action or both.[1] The prevalence of diabetes in the world is 8.3% and in Pakistan is 7.89%.[2] Pakistan is ranked seventh in diabetes prevalence[3] and ranked among top ten countries of the world with population having diabetes in the age group of 20–79 years.[4] Early onset of diabetes is related to higher morbidity and mortality rates.[5,6] The prevalence of the disease is high among females compared to males.[7] Diabetes is a chronic disease with associated complications of obesity, high blood pressure and cholesterol levels.[8] Studies revealed that diabetes mellitus links with micro- and macro-vascular complications such as retinopathies, neuropathies, cardiovascular diseases, nephropathies, cerebrovascular diseases, and abnormal lipid profiles.[8,9] Strict measures such as dietary control, regular exercise, adherence to medications, and monitoring of illness progression suggest preventing disease complications. The complications of the disease somehow increase in the presence of concomitant diseases. Therefore, the patient is required to take an increased number of medications to manage these comorbidities. Thus, the drug-related problems such as adverse effects, drug interactions, and nonadherence to medicines are gradually increasing.[10] Adherence to medications is crucial, especially for patients with chronic diseases for long-term better health outcomes and to cut down the pharmaceutical cost of the therapy. An established 8-item, Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (8-MMAS) is one of the direct subjective methods for the assessment of patient medication adherence toward their therapies. It comprises seven out of eight questions to generate yes/no results and the eighth question further consists of five options’ score divided by 4. Each out of the eight questions comprises 1 score. Scale was adjusted as: <6 = low adherence, 6–< 8 = medium adherence, and 8 = high adherence.[11] Similarly, poor medication compliance results in compromised control of the disease which cites as one of the major barriers to halt disease progression in the developed and developing economies.[12]

METHODS

The current study is an observational study design conducted from June 2015 to October 2015. The study was conducted in a specialized diabetes management center in a tertiary care hospital of Lahore, under the supervision of an endocrinologist, local co-investigator nominated by the departmental head. The study plan was first approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital for research on human beings. A total of 145 participants from the outpatient department (males = 54; females = 91) were included in the current research. Verbal and written informed consents were obtained from the patients before their inclusion as study participants. Glycated hemoglobin (HBA1c) values of all the patients were noted at the start and the end of the survey. Other parameters included a family history, socioeconomic history, and life style pattern. All the recruited participants were on oral antidiabetics, and none of them was receiving insulin therapy. Patients below 18 years of age and above 70 years and pregnant and lactating females were excluded from the study. Each patient was interviewed according to a designed questionnaire for their socioeconomic and sociodemographic status. Data were also collected from patient medication files, needed for follow-up and laboratory reports’ evaluation. Patients were also requested to remain in contact through telephone calls for their further information about their new HBA1c values, 3 months later. Compliance to antidiabetic drugs was noted according to Morisky score (MMAS-8). History of comorbidities was also observed. As per the American Diabetic Association Guidelines (ADA, 2015), HBA1c < 7% and fasting blood glucose < 130 mg/dl were taken as criteria. Patients were also counseled regarding their life style modifications, dietary control, and exercise.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version16.0 and analyzed for descriptive and inferential categorical variables presented as percentages. Chi-square test was applied to test categorical variables and t-test was applied to test quantitative variables. Correlations were also computed between the variables.

RESULTS

Patient demographics

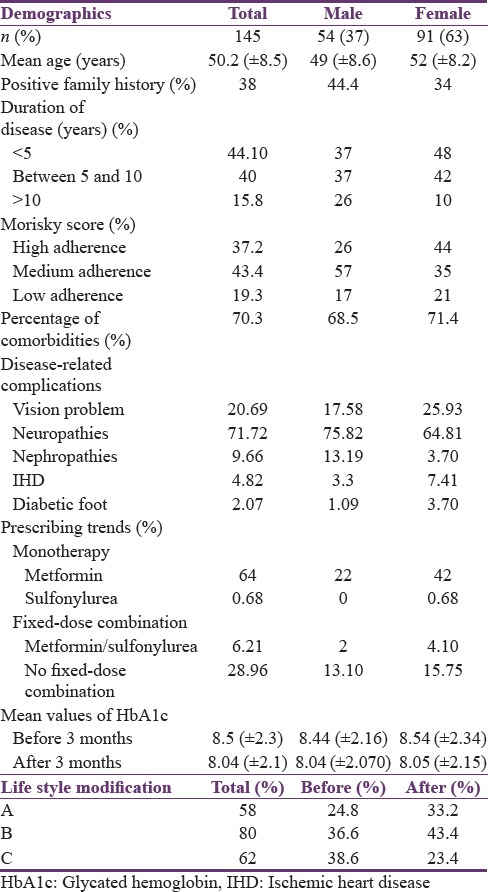

A total of 145 patients having type 2 diabetes mellitus and on oral hypoglycemia were included in the study. Mean age of the patients was 50.2 years (± 8.5); female patients with a mean age of 49 (± 8.6) years and male patients with a mean age of 52 (± 8.2) years. The maximum number of patients (40%) fell in the age group of 50–59 years, followed by 39% in 36–49 years, 12% in 60–69 years, and 6% in 31–35 years. A total of 83% patients were from Lahore while the rest were from other cities of Pakistan. Since diagnosis, 44.1% of the patients fell in the duration of < 5 years, whereas 40% between 5 and 10 years followed by 15.8% patients who suffered from more than 10 years. A total of 38% of patients exhibited a positive family history of diabetes, i.e., in first blood relatives. However, among males, about 44.4% were having a positive history of diabetes in their first blood relatives while it was positive for 34% of females. Patient adherence to the oral hypoglycemic agents was estimated with the help of the 8-MMAS, according to which patients were divided into three categories, i.e., high, medium, and low adherence groups. Nearly 44% of females and 26% of males belonged to high adherence group, while 35% of female and 57% of male patients belonged to medium adherence; however, 21% of female and 17% of male patients belonged to low adherence group. The prevalence of disease complications related to female and male patients on the Medication Adherence Scale is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients

Neuropathy was reported in 75.8% of females and 64.8% of males, nephropathy in 13.2% of females and 0.04% of males, ischemic heart disease in 0.03% of females and 0.07% of males, retinopathy in 17.6% of females and 25.9% of males, and other complications such as diabetic foot and carbuncles in 0.011% of both females and males [Table 2].

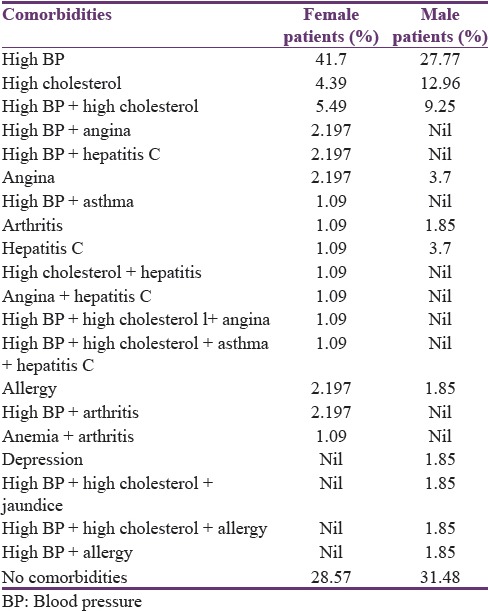

Table 2.

Comorbidities found among female and male diabetic patients

The data regarding comorbidities reported that the most prevalent comorbidity is hypertension (41.7% of females and 27.8% of males).

Prescribing pattern and therapeutic effectiveness

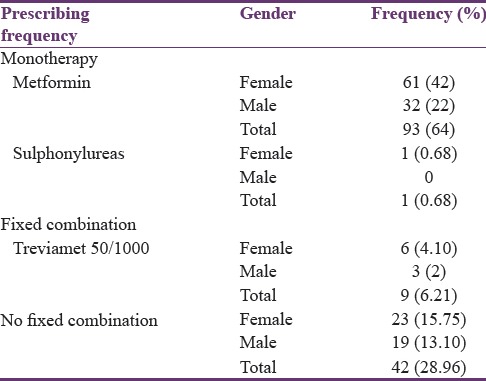

Nearly 71% of prescriptions contained only one antidiabetic, 25.50% with two, 2.10% with three, and 0.60% with four antidiabetics. Almost 64% of patients (males = 22%; females = 42%) were prescribed with metformin as monotherapy and 0.68% were prescribed with sulfonylureas as monotherapy only among female patients. A fixed-dose combination comprising metformin and sulfonylureas was prescribed to 6.21% of patients including 4.10% of female and 2% of male patients. However, 28.96% of patients including 15.75% of females and 13.10% of males were on nonfixed-dose combination therapy [Table 3].

Table 3.

Prescribing frequency of oral hypoglycemic agents (gender-wise distribution)

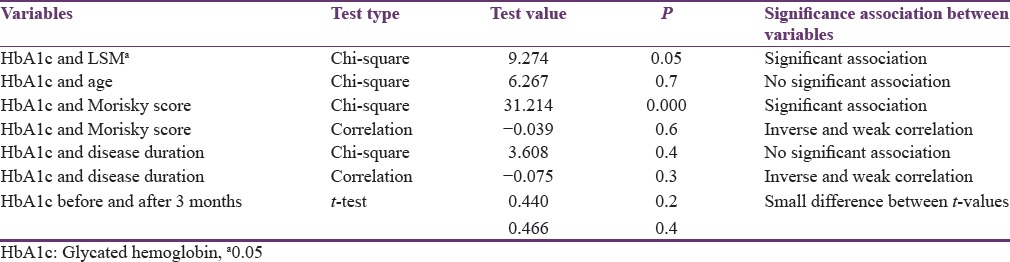

A total of 121 (83.4%) prescriptions were according to the ADA guidelines. HBA1c is the gold standard test to check for glycemic control. Mean HBA1c values calculated at the start and end of the study were 8.5 (± 2.3) and 8.04 (± 2.1), respectively. The average difference was 0.46. Mean HBA1c values calculated at the start and end of the study for female patients were 8.54 (± 2.34) and 8.05 (± 2.15), respectively. Mean HBA1c values calculated at the beginning and end of the survey among male patients were 8.44 (± 2.16) and 8.04 (± 2.07), respectively. Chi-square test showed a significant association between HBA1c and life style modifications (P = 0.05) and between HBA1c values and Morisky score (adherence to medication therapy) (P = 0.00). Chi-square test showed no association between HBA1c and age of patients (P = 0.7) and HBA1c and duration of disease (P = 0.4). Correlation between HBA1c and duration of illness was inverse and weak (−0.075, P = 0.3). Correlation between HBA1c and the Morisky score was also inverse and weak (−0.039, P = 0.6). A t-test applied on HBA1c values collected before and after 3 months showed small differences between values (t = 0.440 and 0.466, respectively) (P = 0.4) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Results of variables on SPSS 16

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the prescribing pattern is indicative of metformin and a small proportion of sulfonylureas prescribed as monotherapy. Among combination therapy, the most common combination was found to be of sitagliptin, sulfonylureas, and metformin. There is no disagreement in the fact that expenses of diabetic management are soaring globally. For the patients in developing countries like Pakistan, it seems hard to afford the cost of diabetic management, and a study revealed average disease management cost of 5542 rupees/month.[13] Based on cost consideration, metformin is the first line of therapy while fixed-dose combination of metformin and sitagliptin is well accepted as second-line choice according to the ADA guidelines and the International Diabetes Federation.[14,15] A total of 16.6% of prescriptions were not in relevance with the international guidelines with HBA1c values >8.5%. HBA1c of ≥7% requires a change of therapy to bring it close to the value of the target. However, individualization of regimen is necessary as it is not possible to take it close to the target value for every patient.[16] The average number of drugs prescribed per prescription was 1.31. HBA1c is the gold standard test for checking glycemic control for the preceding 3 months.[17] The optimal and safe glycemic control indicated using the index of HBA1c < 7% for every average diabetic patient.[14] A t-test comparing the difference of HBA1c at the start and the end of the study shows no significant difference, and the major reason is patient factors of nonadherence to drug therapy and lack of life style modifications. However, this study shows significant association of HBA1c values to life style modifications and adherence to medication therapy. According to another study, for every 10% increase in medication adherence with oral hypoglycemic agents, this helps in a decrease of HBA1c by 0.2%.[18] Patients showing poor adherence to the hypoglycemic drugs are 3 times less likely to show blood glucose control.[19] Unlike other studies, this study shows no association between HBA1c values and age of the patients and duration of disease.[20] This study revealed that a maximum number of patients have < 5 years’ duration which indicates that more new patients are suffering from diabetes.[21] Diabetes is strongly related to family history of illness as the study reported that two-thirds of the patient were with positive family history.[21,22] In this study, 38% of patients showed a positive family history of the disease. Diabetes is among the top five leading causes of mortality, the cause for reducing the quality of life and causing major disabilities.[2] Data collected regarding comorbidities show that the most prevalent comorbidity was high blood pressure. Neuropathy was the most prevalent disease-related complication. The biggest problem faced during the study was patient follow-ups. Most of the patients did not come for the revisits. The second major problem was about data collection regarding HBA1c; this test is not free of charge in public sector hospitals. However, more than 90% of the patients belong to the lower class of the society. As a result, patients were unable to afford the test charges. Some patients also did not give any consideration to get the test performed. The present study highlighted the need for further improvement in prescribing trends. A massive campaign at public level is also required to develop awareness in the society regarding the disease, importance of patient adherence to therapy, and life style modifications. Attention toward the improvement of health-care system relating to the provision of medicines and performance of tests, preferably free of cost, is suggested.

CONCLUSION

The current study demonstrated metformin as the most frequently prescribed oral hypoglycemic agent which seems to be ADA guidelines. However, individualization of treatment is required keeping in view the patient factors. Modification of treatment needs to be incorporated in patients having higher HBA1c values.

Data regarding the therapeutic effectiveness of the oral hypoglycemic agents showed that the drugs were quite effective in lowering of HBA1c values to the target range. However, patient factors such as noncompliance and not following life style modification were hindrances in the achievement of target HBA1c values.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Diabetes Management Centre, SIMS, Lahore, Pakistan, for their support. The corresponding author is grateful for the grant RIGS 15-097-0097, International Islamic University Malaysia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sorkhou I, Hajia A, Al-Qallaf B, El-Batish M. Screening for risk factors in diabetic patients in Mishref area. Kuwait Medical Journal. 2002;34:209–12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103:137–49. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahadar H, Mostafalou S, Abdollahi M. Growing burden of diabetes in Pakistan and the possible role of arsenic and pesticides. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13:117. doi: 10.1186/s40200-014-0117-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whiting DR, Guariguata L, Weil C, Shaw J. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94:311–21. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fazeli Farsani S, van der Aa MP, van der Vorst MM, Knibbe CA, de Boer A. Global trends in the incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents: a systematic review and evaluation of methodological approaches. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1471–88. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2915-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenbloom AL, Silverstein JH, Amemiya S, Zeitler P, Klingensmith GJ. International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2006-2007. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in the child and adolescent. Pediatr Diabetes. 2008;9:512–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group. Liese AD, D’Agostino RB, Jr, Hamman RF, Kilgo PD, Lawrence JM, et al. The burden of diabetes mellitus among US youth: Prevalence estimates from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1510–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Adamo E, Caprio S. Type 2 diabetes in youth: Epidemiology and pathophysiology. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 2):S161–5. doi: 10.2337/dc11-s212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fagot-Campagna A, Burrows NR, Williamson DF. The public health epidemiology of type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents: A case study of American Indian adolescents in the Southwestern United States. Clin Chim Acta. 1999;286:81–95. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(99)00095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type diabetes (UKPDS). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352:837–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plakas S, Mastrogiannis D, Mantzorou M, Adamakidou T, Fouka G, Bouziou A, et al. Validation of the 8-Item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale in Chronically Ill Ambulatory Patients in Rural Greece. Open J Nurs. 2016:6:158–169. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irons BK, Seifert CF, Horton NA. Quality of care of a pharmacist-managed diabetes service compared to usual care in an indigent clinic. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2008;10:220–6. doi: 10.1089/dia.2007.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussain M, Naqvi SBS, Khan MA, Rizvi M, Alam S, Abbas A, et al. Direct cost of treatment of diabetes mellitus. I J Pharm Pharmaceuti Sci. 2014;6:261–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 1):S11–66. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Global IDF/ISPAD. Guideline for Diabetes in Childhood and Adolescence 2011. Berlin, Germany: International Diabetes Federation; 2013. International Society for Paediatric and Adolescence. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, Heine RJ, Holman RR, Sherwin R, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: A consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy: A consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1963–72. doi: 10.2337/dc06-9912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahn R, Hicks J, Muller M, Panteghini M, John G, Deeb L, et al. Consensus statement on the worldwide standardization of the hemoglobin A1C measurement: The American diabetes association, European association for the study of diabetes, international federation of clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine, and the international diabetes federation. Diabet Care. 2007;30:2399–2400. doi: 10.2337/dc07-9925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schectman JM, Nadkarni MM, Voss JD. The association between diabetes metabolic control and drug adherence in an indigent population. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1015–21. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.6.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abebe SM, Berhane Y, Worku A, Alemu S, Mesfin N. Level of sustained glycemic control and associated factors among patients with diabetes mellitus in Ethiopia: A hospital-based cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2015;8:65–71. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S75467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Lawati JA, Barakat MN, Al-Maskari M, Elsayed MK, Al-Lawati AM, Mohammed AJ. HbA1c levels among primary healthcare patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Oman. Oman Med J. 2012;27:465–70. doi: 10.5001/omj.2012.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbas A, Nasir H, Zehra A, Noor A, Jabbar FA, Siddiqui B. Assessment of depression as comorbidity in diabetes mellitus patients using Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI II) Scale. J Young Pharm. 2015;7:206–16. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paul J, Christos PJ, Chemaitelly H, Laith J Abu-Raddad LJ, Mahmoud Ali Zirie MA, Dirk Deleu D, Alvin I Mushlin AI. Prevention of type II diabetes mellitus in Qatar: Who is at risk? Qatar Med J. 2014;2:70–81. doi: 10.5339/qmj.2014.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]