Abstract

Use of statin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has been recommended by most clinical guidelines. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among T2DM patients. It has been proved that statins are effective for primary or secondary CVD prophylaxis. Reports have highlighted the underutilization of statins in clinical practice and the suboptimal adherence to guideline recommendations. This review article points to summarize the current evidence confirming the role of statins in T2DM patients and to provide an overview of factors that may affect statins’ prescribing patterns and compliance in clinical practice. Initiatives to enhance statin therapy prescribing should recognize the comprehensive nature of the prescribing process. Attempts to assure proper statin prescribing and utilization can help in achieving better clinical outcomes of statin therapy.

KEYWORDS: Clinical practice guidelines, dyslipidemia, prescribing patterns, statins, type 2 diabetes mellitus

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in Asia is increasing and has become higher than other regions.[1] Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the major contributor to morbidity and mortality in patients with T2DM.[2] According to the National Health and Morbidity Survey 2015, the prevalence of diabetes in Malaysia was estimated to affect 17.5% of the adult population, with an overall higher prevalence in females as compared to males.[3] Further, in terms of T2DM-related complications, Malaysia has one of the highest prevalence rates of CVD among Asian countries.[4] To decrease the incidence of CVD among Malaysian T2DM patients, many approaches have been implemented.[3] Optimization of the lipid-lowering therapy use among T2DM patients has been considered as one of the significant approaches to decrease the overall CVD burden.[5] People with diabetes have been shown to incur many clinical benefits from lipid-lowering therapy.[6] Statin therapy is considered as the cornerstone of clinician's efforts toward primary and secondary CVD prevention in patients with T2DM.[7] Patients with T2DM are deemed as prime candidates for receiving statin therapy, which has been endorsed by most of the clinical practice guidelines (CPGs).[8,9] Although statins are proven to reduce CVD-related events and all-cause mortality significantly,[10] underutilization of statins in patients at high risk such as those over 40 years with T2DM is reported in the form of inappropriate dosing, discontinuation, and adherence issues.[11] The main objective of this review is to summarize some of the most important clinical guidelines supporting the use of statins in T2DM patients including the recent edition of Malaysian CPGs and finally providing an overview of factors that may affect statins’ prescribing patterns and compliance.

METHODOLOGY

Search was made on Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed for articles with keywords prescribing patterns, statins, diabetes, practice guidelines, and dyslipidemia in their titles or abstracts. Total articles found were 215. A further selection of articles written in English was made. An exclusion to articles with repetitive and/or nonrelevant content was considered after reading all available abstracts. A further selection of relevant articles, available as full-text, that can help in achieving the objectives of this review in terms of providing a comparison between selected guidelines and outlining the potential determinants of statins prescribing for patients with T2DM was made based on authors’ consensus. The final number of articles included in our review was seventy articles.

OVERVIEW OF RECENT CLINICAL GUIDELINES FOR DIABETIC DYSLIPIDEMIA

European Society of Cardiology 2013 guidelines on diabetes and cardiovascular diseases

In the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) 2013 guidelines, statins were recommended for primary prophylaxis in patients with T2DM who do not have any other cardiovascular (CV) risk factor and free of target organ damage, with an low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) target of < 2.5 mmol/L (<100 mg/dl).[8] Meanwhile, for secondary prophylaxis, statins were recommended for patients with T2DM associated with documented CVD or with one or more CV risk factors. The secondary prophylaxis target for LDL-C is <1.8 mmol/L (<70 mg/dl) or a lipid-lowering target percentage in LDL-C reduction is ≥50% if the target goal cannot be reached.[8] The ESC guidelines emphasized the positive relationship between LDL-C reduction and CVD risk prevention.[12] In addition, the beneficial statin effect of intensive LDL-C lowering on the pathophysiology of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with T2DM has also been reported.[13] Although having been on LDL-C lowering therapy, patients with diabetes may still be at a residual risk of developing CVD events, for which a combination therapy or further intensification of LDL-C lowering therapy may play a role after taking into consideration the potential safety concerns.[14] Recently, in the ESC 2016 guidelines for CVD prevention in clinical practice, a risk stratification for patients with T2DM to high-risk and very high-risk groups was considered for setting different treatment LDL-C targets.[15] Finally, ESC guidelines did not recommend using drug therapy to target high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) elevation to reduce the CVD risk in susceptible patients.[16]

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association 2013 guidelines for the management of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in adults:

In the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2013 guidelines, T2DM patients over the age of 40 years were among the four major statins benefit groups that require focused efforts to reduce CVD events as a primary or secondary prophylaxis.[9] Patients with diabetes between 40 and 75 years and LDL-C of 70–189 mg/dl (1.8–4.9 mmol/L) and without coronary artery disease or stroke are ideal candidates to receive statin therapy as a primary prophylaxis. Moreover, if patients with diabetes had already documented coronary artery disease or stroke, there was more emphasis on receiving statins as a fundamental part of their therapeutic plan for secondary CVD prophylaxis. According to their expected average LDL-C reduction, statins have been classified by fixed doses to high-, moderate-, and low-intensity therapy with an added clinical benefit for LDL-C reduction.[17]

Statin treatment strategy for primary prophylaxis in patients with T2DM should involve either moderate or high intensity. The choice of regimen should be individualized according to benefits of CVD risk reduction, patient preferences, and safety issues.[9] Unless there is patients’ safety or tolerability concerns, high-intensity statins should be used for the secondary prophylaxis regimen.[18] A new tool for risk assessment in these guidelines has conferred some new changes to the paradigm of CVD risk assessment in terms of family history exclusion, stroke risk inclusion, and lowering high-risk threshold to ≥7.5% instead of ≥10%.[19] Several studies have been conducted to evaluate accuracy and efficiency of recommendations made in the ACC/AHA guidelines.[20]

One USA study estimated the number of persons who were eligible to receive statin therapy and extrapolated the results to a population of 115.4 million USA adults between the ages of 40 and 75 years. The results showed an increasing trend in the total number of adults eligible to receive statin therapy, especially among older adults without CVD.[21] Another interesting study was conducted in Europe to assess the impact of the application of the ACC/AHA 2013 guideline recommendations in comparison with the ESC 2013 guidelines and Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. The application of ACC/AHA 2013 guidelines has increased the number of patients being eligible to benefit from statins therapy in this European population especially those aged 55 years or older.[22]

American Diabetes Association 2016 standards of medical care in diabetes

In accordance with what have been recommended earlier by ACC/AHA guidelines, American Diabetes Association standards of care recommend moderate-intensity statins for all T2DM patients over the age of 40 years as a primary prophylaxis.[23] On the other hand, higher doses of statins are required for the secondary prophylaxis of diabetic patients with coronary artery disease or at increased CVD risk such as those with abnormal LDL-C levels, smokers, hypertension, or albuminuria.[24]

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2014 guidelines on cardiovascular disease risk assessment, reduction, and lipid modification

These guidelines suggest offering atorvastatin 20 mg for primary prophylaxis for patients with T2DM who have at least 10% 10-year CVD risk as assessed using the QRISK2 risk assessment tool.[25] Furthermore, for secondary prophylaxis of patients with T2DM who have had CVD, the practice standards recommend early use of higher doses of statins, for example, atorvastatin 80 mg with a possible use of lower doses depending on the expected side effect profile and patients’ treatment priorities.[25]

Malaysian clinical practice guidelines for treatment of type 2 diabetes 2015

According to the Malaysian CPG, for the purpose of primary CVD prophylaxis, all T2DM patients over the age of 40 years should be offered a statin therapy regardless of baseline LDL-C measures based on the findings of two large studies.[26,27] The target of LDL-C in those patients was set to be 2.6 mmol/L. If this target was not achievable, the plan should target a reduction in the LDL-C by 50% from the pretherapy measures.[9] The same recommendations were applied to T2DM patients with explicit CVD but with a much lower target of LDL-C that was 1.8 mmol/L or a 50% reduction in LDL-C as compared to prestatin levels.[28] Although non-HDL-C may be considered as a better predictor of CVS risk in patients with diabetes, it remained as a secondary treatment target due to the lack of sufficient evidence to support the superiority of treatment approach that targets non-HDL-C rather than LDL-C.[29] In comparison with the American guidelines, the Malaysian CPG similar to the ESC guidelines has not emphasized on a particular statin intensity that should be used per certain patients’ group which may be attributed to the difference in CVD risk estimation tool used by these guidelines.

In summary, all the guidelines presented above showed great similarities between recommendations suggested by different clinical professional bodies, especially in terms of the overall consensus that statins make up a substantial component for the treatment of diabetic dyslipidemia that can have a deterrent impact on both CVD events and mortality.[30] The essential role of the preventive path of CVD in diabetes was based primarily on the fact that diabetes patients have a similar risk profile of CVD-related death when compared to patients without diabetes but has had an episode of acute coronary syndrome in the past.[31] In addition, although lifestyle modifications involving dietary changes and physical exercise were found to help improve glucose and lipid measure in diabetic dyslipidemia, especially in overweight patients, it failed to show any CVS mortality benefit.[32]

THE RECOMMENDED STATIN DOSE

The majority of recommendations have endorsed the use of moderate intensity statins for T2DM patients over the age of 40 years without specifying fixed doses, except for the ACC/AHA 2013 and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. It has been suggested by the ACC/AHA 2013 guidelines to use fixed doses of different statins classified according to their capacity for LDL-C reduction.[33] Concurrently, the same approach has been employed by the NICE guidelines which suggested two different doses of atorvastatin (20 and 80 mg) be used in diabetes patients for primary and secondary CVD prophylaxis, respectively.

In addition, it has been proposed that further increasing the statin therapy dose may be needed to attain very low LDL-C below the previously accepted targets, for example, 40–50 mg/dl (0.9–1.1 mmol/L), on the basis that the correlation between CVD risk and LDL-C in diabetic patients, was more robust at this level.[34] According to the most recent evidence, this approach of targeting very low LDL-C levels has failed to show any additional benefit among patients with preexisting ischemic heart disease in comparison with the target LDL-C levels recommended by most of the CPGs.[35] It has been shown in the literature that early use of statins for primary prophylaxis was associated with higher long-term CVD prophylaxis.[36] Further, it was reported that using statins in prediabetic individuals may confer a lower CVD risk.[37] In general, increasing statin dose should be considered before resorting to combination therapy in the case of unachievable or suboptimal LDL-C levels.[38] The assessment of the clinical benefit of using combination therapy in comparison with a higher statin dose has shown some improvement in lipid measures without a proportionate effect on the overall clinical outcome.[32]

THE COMBINATION THERAPY

Combination therapy can be considered if there is statin tolerance or safety issues or if the patient has already been offered the highest approved statin doses without reaching the LDL-C targets.[39,40] Although the reporting of statins’ adverse effects has been increased, especially among patients received more intense statin dosing, the overall benefit of their use is deemed too far outweigh the potentially increased risk.[41]

Incidentally, a summary of findings for large statin randomized trials has failed to show a correlation between incidences of adverse effects (e.g., elevation of liver enzymes, rhabdomyolysis) and the increased degree of LDL-C reduction by higher potency statins. They suggest that adverse effects may be more correlated with a certain statin at a specific dose such as simvastatin 80 mg.[42] Similarly, a meta-analysis of 26 randomized controlled trials showed that further LDL-C reduction is associated with a reduction in major adverse CV events and suggested that high-intensity statins are safe to be recommended either as atorvastatin 80 mg or a combination of simvastatin 40 mg with other lipid-lowering medications.[17]

There are several medications including ezetimibe, fenofibrate, niacin, and omega-3 fats, which can be used in combination therapy for achieving the further LDL-C reduction and favorable effects on levels of triglycerides and non-HDL-C.[43] In a recent study which looked at comparing between combination therapy and high-intensity statins in diabetic patients with CVD, a more favorable lipoprotein effect was observed in the combination therapy (simvastatin-ezetimibe) as compared to high-intensity statins (atorvastatin or rosuvastatin).[44] In addition, the ezetimibe-statin combination therapy has been associated with a lower incidence of major adverse cardiac events.[45] The good results showed in the ezetimibe trial has been reflected in the Malaysian CPG recommendation of this therapy as a second-line treatment for LDL-C reduction.[46]

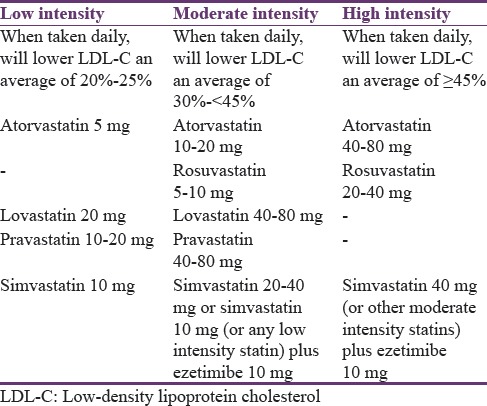

In a recent study on lipid-lowering therapy patterns among type 2 diabetic patients at high CVD risk, frequent incidence of treatment intolerances was observed at higher doses of statin therapy and contributed to the low statin prescription rate despite the obvious clinical indication.[47] Therefore, it seems that the use of combination therapy may need to be promoted further for optimal management of diabetic dyslipidemia to reduce the overall CVD burden.[5] Classification of statins and the proposed statin combination therapy are provided in Table 1.[48]

Table 1.

Classifications of statins intensity and the combination therapy

STATINS’ PRESCRIBING AND ADHERENCE TO PRACTICE GUIDELINES

After reviewing some of the important clinical evidence recommending the use of statin therapy in patients with T2DM, we aimed in this section to underpin what can affect the complete reflection of those recommendations in the daily clinical practice. A primary review focused on identifying barriers to prescribers’ adherence to clinical guidelines has provided a comprehensive framework of barriers affecting prescribing determinants which are knowledge, attitude, and behavior.[49] This review was sought to extend the concepts of the above-mentioned framework for prescribing of statins in diabetes patients.

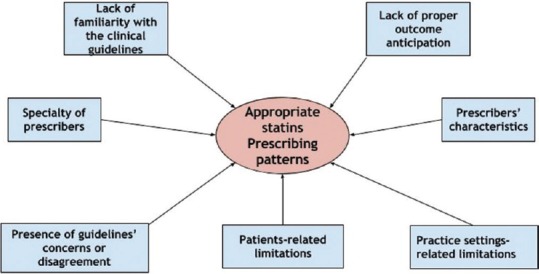

In the real-world practice, the prescribing of statins in diabetes will never fully adopt the pattern outlined by the clinical guidelines.[50] Numerous factors have been reported to affect the suboptimal adherence to the prescribing evidence suggested by the clinical guidelines.[51] First, clinicians may not be fully aware or familiar with newer recommendations or clinical guidelines.[52] Lack of familiarity with the clinical guidelines is a common barrier to their implementation in clinical practice.[53] For example, inaccuracies in statins prescribing involve both statin type and dosage. In a study conducted by Teeling et al., it has been found that although the overall prescribing rate may increase in response to guideline recommendations, it is still common for practitioners to prescribe lower doses than those recommended by clinical guidelines.[54]

Furthermore, in a study involved more than 300 physicians, it has been shown that there was a lack of proper outcome anticipation among physicians with regard to different statin dosages. The findings underscored the variable prescription patterns utilized by different physicians within the same field and thereby resulting in an incomplete realization of statin therapy full effects.[55] Moreover, inaccurate risk estimation highlighted by Pignone et al. is also a major factor resulting in inappropriate prescribing of statin therapy.[56]

In addition, the specialty of prescribers also affects the way in which statins are prescribed. One study comparing the assessment of CVD risk between cardiologists and general practitioners has revealed that a more precise estimation of the CVD risk was provided by cardiologists rather than general practitioners.[57] This will naturally temper the choice and dosage of statins utilized in primary prevention of CVD. Prescribers’ characteristics can also play a role, especially in terms of their motivation and readiness to change their prescribing behavior.[58] The variability in prescribing patterns of different practitioners may simply be the manifestation of the perceived degree of self-efficacy and belief in one's actual ability to manage statin use.[49,59]

A less common scenario that may affect prescribing adherence to guidelines is the presence of concerns or disagreement with the final recommendations or the way by which the guidelines were formulated.[60,61] In addition, clinicians’ biased perceptions about statin side effects may negatively affect their prescribing pattern and thus increase the overall CVD risk in a particular individual.[62]

Finally, many other factors can also play a role in the prescribing process such as patient-related limitations[63] such as financial issues or perceived medication's risk and practice setting-related limitations[64] such as lack of resources and/or lack of time. Figure 1 represents a summary of factors affecting prescribing patterns of clinicians and their adherence to clinical guidelines.

Figure 1.

Factors affecting statins prescribing patterns

COMPLIANCE TO STATIN THERAPY

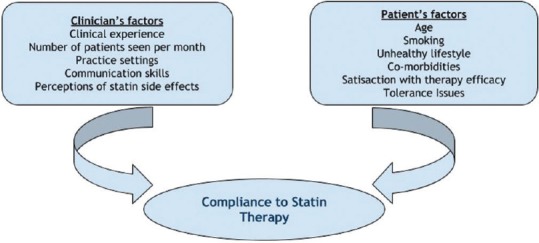

It is clear that prescribing behavior is not only the important determinant in achieving the overall statin treatment outcomes. After prescribing, of the next major stumbling block will be patient's compliance. Failure to comply with prescribed statin treatment results in both wastage of resources and a missed opportunity for CVD prophylaxis.[65] Many factors can influence the degree of compliance to statin treatment which can be classified as either pertinent to patient or clinician. Patient's pertinent factors include older age, smoking, lack of exercise, nonhealthy diet, comorbidities, and adverse reactions while physicians’ related factors encompass clinical experience, number of dyslipidemic patients seen per month, and hospital settings.[66] In addition, patients’ own perceptions about statin safety may negatively affect the utilization of lipid-lowering treatment and increase the overall CVD risk in a particular individual.[65]

Safety issues

The main potential adverse reactions to statin therapy are the elevation in hepatic enzymes, myopathy, and increased risk of diabetes.[67] Regarding liver safety issues, statins are considered safe for use even in patients with mild to moderate elevation in liver enzymes in nonalcoholic patients.[68] Withholding statin therapy should only be considered when the abnormality in hepatic enzymes exceeds three times the upper normal limit.[69] Statin-associated muscle symptoms are the most frequent causes of statin intolerance in clinical practice although those problems do not often progress to severe myopathy or rhabdomyolysis.[69] Physicians or prescribers are required to perform baseline investigations for both liver and muscle toxicities before statin prescription.[70] An assessment of myopathy enhancers either medical conditions or drug therapies[48] is recommended while dealing with statin-intolerant patients. As the trend of the negative statin therapy perceptions is increasing due to misleading safety claims or unbalanced media coverage,[71] further robust and valid estimation of statin intolerance is needed. In this regard, the ACC has released “statin intolerance” medical app to help clinicians toward the objective assessment of statin-associated muscle symptoms.[72] Although the risk of new-onset diabetes has been shown in the literature,[73] it is reported that statins are not commonly associated with any glycemic disturbances in those patients who are already having diabetes.[48] Moreover, statin therapy use among patients with T2DM has been associated with absolute benefits in terms of CVD prevention, while there is no evidence of causal relationship between any excess in T2DM microvascular complications and the use of statin therapy.[74]

Furthermore, it is imperative to realize that the quality of clinician–patient relationship and the degree of patient's satisfaction by treatment efficacy are also crucial determinants of patient's compliance behavior.[75]

Figure 2 shows a summary of patient's and clinician's factors that can affect compliance with statin therapy.

Figure 2.

Factors affecting patients compliance to statin therapy

Many initiatives can help in improving patients’ compliance to statin treatment.[76] Pharmacist-led lipid management clinics are reported to have a favorable impact on achieving lipid treatment outcomes.[77] Moreover, telephone follow-up and periodical counseling have been shown to be helpful in this regard.[78] Overall, the effective communication between healthcare practitioners and their patients can address many patient's compliances or tolerance issues, especially those related to statin side effects.[79]

CONCLUSION

Adherence to clinical guidelines that recommend statins for T2DM patients as the main CVD prophylaxis treatment is modulated by many factors. These determinants may play a crucial role in ensuring success following the decision to prescribe statins. Moreover, having prescribed statins, some factors related to both clinicians and patients alike, can also affect compliance to statin therapy. Initiatives to enhance statin therapy prescribing should recognize the comprehensive nature of the prescribing process. Efforts to assure proper statin utilization and prescribing may help in achieving better clinical outcomes of statin therapy among patients with T2DM.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yoon KH, Lee JH, Kim JW, Cho JH, Choi YH, Ko SH, et al. Epidemic obesity and type 2 diabetes in Asia. Lancet. 2006;368:1681–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackowski L, Crockett J, Rowett D. Lipid lowering therapy for adults with diabetes. Aust Fam Physician. 2008;37:39–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute for Public Health. National Health and Morbidity Survey 2015 (NHMS 2015). Vol. II: Non-Communicable Diseases, Risk Factors and Other Health Problems. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohamed M Diabcare-Asia Study Group. An audit on diabetes management in Asian patients treated by specialists: The Diabcare-Asia 1998 and 2003 studies. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:507–14. doi: 10.1185/030079908x261131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.A SF, Kamarudin A, NNAN O, Sivasampu S, Rosliza L, Rosaida MS, et al. Malaysian Statistics On Medicines 2009 & 2010 Report. Pharmaceutical Services Division and the Clinical Research Centre Ministry Of Health. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung BM. Statins for people with diabetes. Lancet. 2008;371:117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pursnani A, Massaro JM, D’Agostino RB, Sr, O’Donnell CJ, Hoffmann U. Guideline-based statin eligibility, coronary artery calcification, and cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2015;314:134–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rydén L, Grant PJ, Anker SD, Berne C, Cosentino F, Danchin N, et al. ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD: The Task Force on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and developed in collaboration with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3035–87. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889–934. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaRosa JC, He J, Vupputuri S. Effect of statins on risk of coronary disease: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1999;282:2340–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin I, Sung J, Sanchez RJ, Mallya UG, Friedman M, Panaccio M, et al. Patterns of statin use in a real-world population of patients at high cardiovascular risk. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22:685–98. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.6.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Collins R, Keech A, Simes J, et al. Efficacy of cholesterol-lowering therapy in 18,686 people with diabetes in 14 randomised trials of statins: A meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371:117–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60104-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicholls SJ, Tuzcu EM, Kalidindi S, Wolski K, Moon KW, Sipahi I, et al. Effect of diabetes on progression of coronary atherosclerosis and arterial remodeling: A pooled analysis of 5 intravascular ultrasound trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:255–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chapman MJ, Ginsberg HN, Amarenco P, Andreotti F, Borén J, Catapano AL, et al. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease: Evidence and guidance for management. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1345–61. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR) Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315–81. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Abt M, Ballantyne CM, Barter PJ, Brumm J, et al. Effects of dalcetrapib in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2089–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, Holland LE, Reith C, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: A meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Final Report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amin NP, Martin SS, Blaha MJ, Nasir K, Blumenthal RS, Michos ED. Headed in the right direction but at risk for miscalculation: A critical appraisal of the 2013 ACC/AHA risk assessment guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt A):2789–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rhee EJ, Park SE, Oh HG, Park CY, Oh KW, Park SW, et al. Statin eligibility and cardiovascular risk burden assessed by coronary artery calcium score: Comparing the two guidelines in a large Korean cohort. Atherosclerosis. 2015;240:242–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pencina MJ, Navar-Boggan AM, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Williams K, Neely B, Sniderman AD, et al. Application of new cholesterol guidelines to a population-based sample. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1422–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kavousi M, Leening MJ, Nanchen D, Greenland P, Graham IM, Steyerberg EW, et al. Comparison of application of the ACC/AHA guidelines, Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines, and European Society of Cardiology guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in a European cohort. JAMA. 2014;311:1416–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2016. Am Diabetes Assoc. 2016;37:14–80. [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Lemos JA, Blazing MA, Wiviott SD, Lewis EF, Fox KA, White HD, et al. Early intensive vs. a delayed conservative simvastatin strategy in patients with acute coronary syndromes: Phase Z of the A to Z trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1307–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabar S, Harker M, O’Flynn N, Wierzbicki AS Guideline Development Group. Lipid modification and cardiovascular risk assessment for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2014;349:g4356. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins R, Armitage J, Parish S, Sleigh P, Peto R Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin in 5963 people with diabetes: A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:2005–16. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13636-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colhoun HM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, Hitman GA, Neil HA, Livingstone SJ, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): Multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:685–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16895-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Rader DJ, Rouleau JL, Belder R, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495–504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang R, Schulze MB, Li T, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, et al. Non-HDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein B predict cardiovascular disease events among men with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1991–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.8.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mills EJ, Rachlis B, Wu P, Devereaux PJ, Arora P, Perri D. Primary prevention of cardiovascular mortality and events with statin treatments: A network meta-analysis involving more than 65,000 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1769–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mooradian AD. Cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Current management guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:33–40. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warraich HJ, Wong ND, Rana JS. Role for combination therapy in diabetic dyslipidemia. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17:32. doi: 10.1007/s11886-015-0589-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith SC, Jr, Grundy SM. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline recommends fixed-dose strategies instead of targeted goals to lower blood cholesterol. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:601–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB, Jr, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–39. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leibowitz M, Karpati T, Cohen-Stavi CJ, Feldman BS, Hoshen M, Bitterman H, et al. Association between achieved low-density lipoprotein levels and major adverse cardiac events in patients with stable ischemic heart disease taking statin treatment. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1105–13. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ford I, Murray H, Packard CJ, Shepherd J, Macfarlane PW, Cobbe SM West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group. Long-term follow-up of the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1477–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bitzur R. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: When it comes to lipids, statins are all you need. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 2):S380–2. doi: 10.2337/dc11-s256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mooradian AD. Drug therapy of diabetic dyslipidemia: Do the statins suffice? Am J Ther. 2015;22:87–8. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e318293b0f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mooradian AD. Dyslipidemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2009;5:150–9. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gudzune KA, Monroe AK, Sharma R, Ranasinghe PD, Chelladurai Y, Robinson KA. Effectiveness of combination therapy with statin and another lipid-modifying agent compared with intensified statin monotherapy: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:468–76. doi: 10.7326/M13-2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhatia L, Byrne CD. There is a slight increase in incident diabetes risk with the use of statins, but benefits likely outweigh any adverse effects in those with moderate-to-high cardiovascular risk. Evid Based Med. 2010;15:84–5. doi: 10.1136/ebm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alsheikh-Ali AA, Maddukuri PV, Han H, Karas RH. Effect of the magnitude of lipid lowering on risk of elevated liver enzymes, rhabdomyolysis, and cancer: Insights from large randomized statin trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:409–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bell DS, Al Badarin F, O’Keefe JH., Jr Therapies for diabetic dyslipidaemia. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:313–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Le NA, Tomassini JE, Tershakovec AM, Neff DR, Wilson PW. Effect of switching from statin monotherapy to ezetimibe/simvastatin combination therapy compared with other intensified lipid-lowering strategies on lipoprotein subclasses in diabetic patients with symptomatic cardiovascular disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001675. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang SH, Wu LS, Lee CH, Kuo CT, Liu JR, Wen MS, et al. Simvastatin-ezetimibe combination therapy is associated with a lower rate of major adverse cardiac events in type 2 diabetics than high potency statins alone: A population-based dynamic cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2015;190:20–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malaysian Clinical Practice Guideline. Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. 2015. [Last accessed on 2017 Apr]. pp. 1–129. Available at: http://www.moh.gov.my/englishphp/pages/view/212 .

- 47.Quek RG, Fox KM, Wang L, Li L, Gandra SR, Wong ND. Lipid-lowering treatment patterns among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with high cardiovascular disease risk. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2015;3:e000132. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2015-000132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grundy SM. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with statins: Assessing the evidence base behind clinical guidance. Clin Pharm. 2016;8:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langner NR, Hasselback PD, Dunkley GC, Corber SJ. Attitudes and practices of primary care physicians in the management of elevated serum cholesterol levels. CMAJ. 1989;141:33–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohlsson H, Lindblad U, Lithman T, Ericsson B, Gerdtham UG, Melander A, et al. Understanding adherence to official guidelines on statin prescribing in primary health care – A multi-level methodological approach. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:657–65. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0975-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feldman EL, Jaffe A, Galambos N, Robbins A, Kelly RB, Froom J. Clinical practice guidelines on depression: Awareness, attitudes, and content knowledge among family physicians in New York. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:58–62. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Balk SJ, Landesman LY, Spellmann M. Centers for disease control and prevention lead guidelines: Do pediatricians know them? J Pediatr. 1997;131:325–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Teeling M, Bennett K, Feely J. The influence of guidelines on the use of statins: Analysis of prescribing trends 1998-2002. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:227–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lytsy P, Burell G, Westerling R. How do prescribing doctors anticipate the effect of statins? J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17:420–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pignone M, Phillips CJ, Elasy TA, Fernandez A. Physicians’ ability to predict the risk of coronary heart disease. BMC Health Serv Res. 2003;3:13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friedmann PD, Brett AS, Mayo-Smith MF. Differences in generalists’ and cardiologists’ perceptions of cardiovascular risk and the outcomes of preventive therapy in cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:414–21. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-4-199602150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Young JM, Ward JE. Implementing guidelines for smoking cessation advice in Australian general practice: Opinions, current practices, readiness to change and perceived barriers. Fam Pract. 2001;18:14–20. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grol R. National standard setting for quality of care in general practice: Attitudes of general practitioners and response to a set of standards. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40:361–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grilli R, Magrini N, Penna A, Mura G, Liberati A. Practice guidelines developed by specialty societies: The need for a critical appraisal. Lancet. 2000;355:103–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Soran H, Schofield JD, Durrington PN. Cholesterol, not just cardiovascular risk, is important in deciding who should receive statin treatment. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2975–83. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rzouq FS, Volk ML, Hatoum HH, Talluri SK, Mummadi RR, Sood GK. Hepatotoxicity fears contribute to underutilization of statin medications by primary care physicians. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:89–93. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181e15da8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elnicki DM, Morris DK, Shockcor WT. Patient-perceived barriers to preventive health care among indigent, rural Appalachian patients. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:421–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jackson L, Yuan L. Family physicians managing tuberculosis. Qualitative study of overcoming barriers. Can Fam Physician. 1997;43:649–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simons LA, Levis G, Simons J. Apparent discontinuation rates in patients prescribed lipid-lowering drugs. Med J Aust. 1996;164:208–11. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb94138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim YS, Sunwoo S, Lee HR, Lee KM, Park YW, Shin HC, et al. Determinants of non-compliance with lipid-lowering therapy in hyperlipidemic patients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11:593–600. doi: 10.1002/pds.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wilkinson MJ, Laffin LJ, Davidson MH. Overcoming toxicity and side-effects of lipid-lowering therapies. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;28:439–52. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Athyros VG, Tziomalos K, Gossios TD, Griva T, Anagnostis P, Kargiotis K, et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term statin treatment for cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease and abnormal liver tests in the Greek Atorvastatin and Coronary Heart Disease Evaluation (GREACE) Study: A post-hoc analysis. Lancet. 2010;376:1916–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61272-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arca M, Pigna G. Treating statin-intolerant patients. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2011;4:155–66. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S11244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sikka P, Kapoor S, Bindra VK, Sharma M, Vishwakarma P, Saxena KK. Statin intolerance: Now a solved problem. J Postgrad Med. 2011;57:321–8. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.90085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yusuf S, Collaborators CTT (CTT) Armitage J, Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, et al. Why do people not take life-saving medications? The case of statins. [Last accessed on 2017 Feb];Lancet. 2016 388:943–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31532-X. Available from: http://www.linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S014067361631532X . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.ACC Statin Intolerance App – American College of Cardiology. [Last cited on 2017 Mar 18]. Available from: http://www.acc.org/StatinIntoleranceApp .

- 73.Zaharan NL, Williams D, Bennett K. Statins and risk of treated incident diabetes in a primary care population. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75:1118–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Collins R, Reith C, Emberson J, Armitage J, Baigent C, Blackwell L, et al. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet. 2016;388:2532–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kiortsis DN, Giral P, Bruckert E, Turpin G. Factors associated with low compliance with lipid-lowering drugs in hyperlipidemic patients. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2000;25:445–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2000.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bramlet DA, King H, Young L, Witt JR, Stoukides CA, Kaul AF. Management of hypercholesterolemia: Practice patterns for primary care providers and cardiologists. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:39H–44H. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00819-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cording MA, Engelbrecht-Zadvorny EB, Pettit BJ, Eastham JH, Sandoval R. Development of a pharmacist-managed lipid clinic. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:892–904. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Faulkner MA, Wadibia EC, Lucas BD, Hilleman DE. Impact of pharmacy counseling on compliance and effectiveness of combination lipid-lowering therapy in patients undergoing coronary artery revascularization: A randomized, controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:410–6. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.5.410.35048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Ito MK, Jacobson TA. Understanding Statin Use in America and Gaps in Patient Education (USAGE): An internet-based survey of 10,138 current and former statin users. J Clin Lipidol. 2012;6:208–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]