Abstract

Alkaptonuria is a rare inborn error of metabolism with autosomal recessive inheritance with a mutation in homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase. It results in accumulation of homogentisic acid in connective tissues (ochronosis). Most common ocular manifestations are bluish-black discoloration of the conjunctiva, cornea, and sclera. In this case report, a 39-year-old Indian male patient with additional ocular features in the retina is described.

Keywords: Alkaptonuria, ochronosis, ocular manifestations of ochronosis

Alkaptonuria (AKU), the first defined human genetic disease with a recessive trait, is caused by mutations within the homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase (HGD) gene (3q13.33). This inborn error in the metabolism of phenylalanine and tyrosine is characterized by the inability to metabolize homogentisic acid (HGA). The raised HGA levels in plasma and extracellular fluid lead to ochronosis, the deposition of polymers of HGA as a pigment (ochronotic pigment) in the connective tissues including cartilage, heart valves, and sclera.[1,2] The distribution of this disease is equal in males and females because it is an autosomal recessive or autosomal dominant trait. The most common ocular manifestations include bluish-black discoloration (ochronotic pigments) of the conjunctiva, cornea, and sclera. In this case report, a 39-year-old Indian male with some additional ocular manifestations is described.

Case Report

A 39-year-old male patient was referred to our outpatient department for ophthalmic evaluation. His chief complaint was blackish discoloration of both eyes for the past 6 months. The patient gave a history of knee joint pains and stiffness of metacarpal joints for the past 10 months.

On general examination, there was bluish-black discoloration of palms, [Figs. 1 and 2], feet, and cartilage of ear pinna [Fig. 3].

Figure 1.

Palms showing bluish-black discoloration

Figure 2.

Nails and dorsum of hands showing bluish-black discoloration

Figure 3.

Cartilage of pinna showing bluish-black pigmentation

Ocular examination

Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/40 in the left eye, with refractive correction of −0.25 D sph/−0.75 D cyl × 180° in the right eye and −1.25 D cyl × 180° in the left eye. Near vision was N6 in both eyes. On slit lamp examination, there was bluish-black discoloration of conjunctiva and sclera in the interpalpebral area both the eyes [Figs. 4 and 5]. Cornea of both eyes was clear. Anterior chamber was quiet. Pupils were normal size reacting to light. Lens was clear. Applanation tonometry was 14 mmHg both eyes. Gonioscopy revealed open angles. Fundus examination with 90D lens showed normal optic disc and vessels in both eyes. Both eyes showed epiretinal membrane in the macular area with macular puckering in the left eye [Fig. 6]. An optical coherence tomography was done for both the eyes which confirmed the presence of epiretinal membrane in both eyes [Figs. 7 and 8].

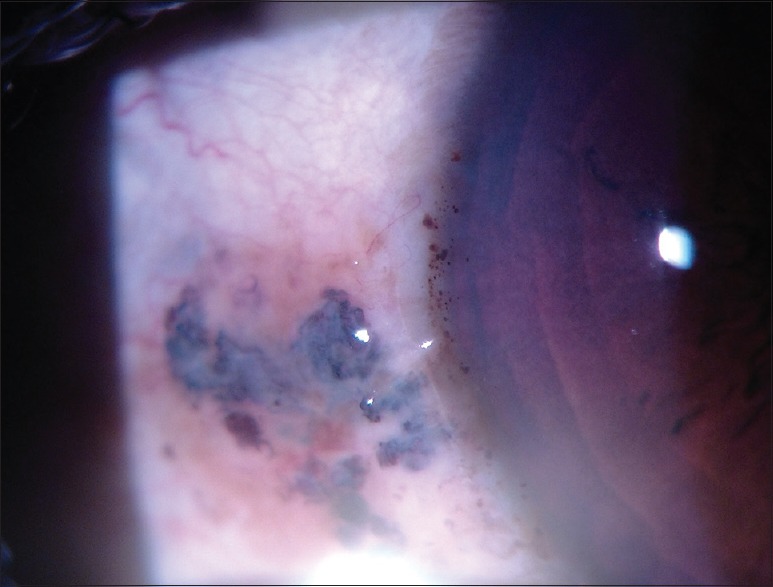

Figure 4.

Bluish-black discoloration of episclera and sclera

Figure 5.

Slit lamp photograph showing bluish-black pigmentation of episclera and sclera

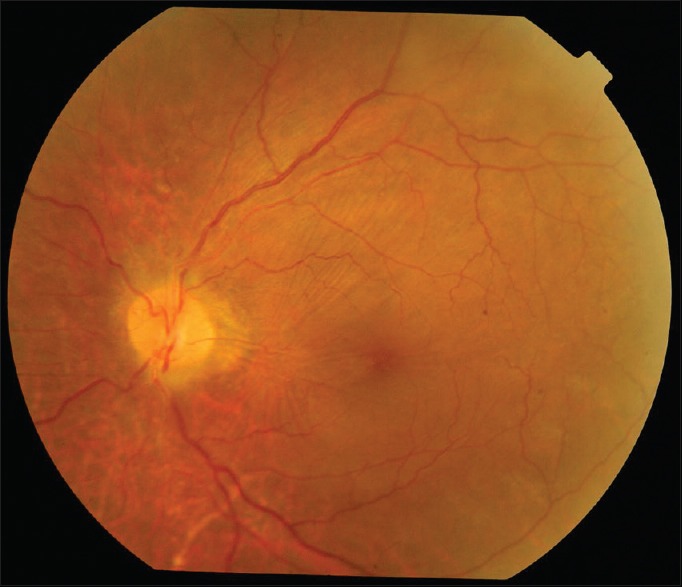

Figure 6.

Left eye fundus picture: Epiretinal membrane with macular puckering

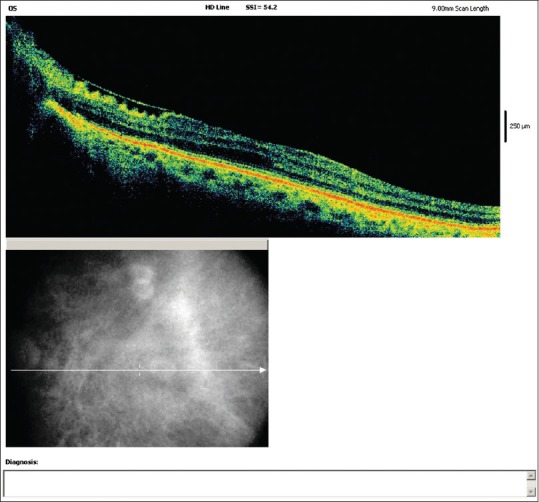

Figure 7.

Left eye optical coherence tomography showing epiretinal membrane

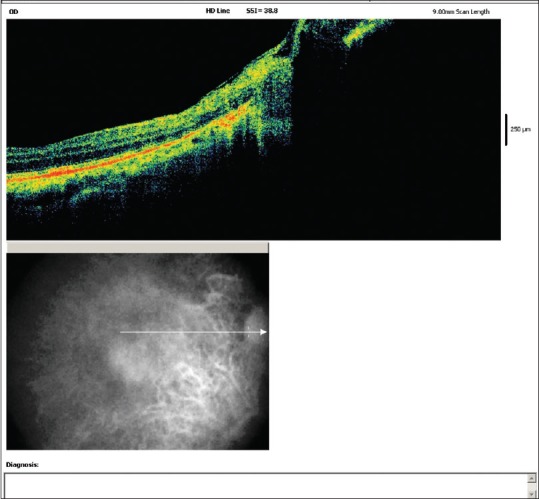

Figure 8.

Right eye optical coherence tomography showing epiretinal membrane

Systemic investigations

Complete blood picture was within normal limits. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 24 mm/1st h, complete urine examination was normal, but the color of the urine turned dark on exposure to atmosphere [Fig. 9].

Figure 9.

Color of the urine turned dark on exposure to atmosphere

Serum uric acid was 5.8 mg/dl. Ultrasound abdomen was normal. Electrocardiography was normal. Liver function tests showed elevated alkaline phosphatase. Rheumatoid arthritis factor was negative. C-reactive protein was negative. X-rays of knee joints and dorsolumbar spine showed degenerative changes such as joint space narrowing, osteophyte formation, loose bodies, subchondral sclerosis, and extensive soft tissue calcifications in anterolateral compartment of both knee joints. The lumbar lateral X-ray showed extensive diffuse intervertebral disc calcifications at multiple levels with vacuum phenomenon, disc space narrowing, marginal osteophytes, and superior and inferior endplate changes of all dorsolumbar vertebral levels.

Treatment

The patient was started on Vitamin C 1 g daily and was given refractive correction to both eyes. He was advised for epiretinal membrane peeling in the left eye. However, the patient was not willing for surgical intervention. We have referred the patient to Orthopaedic Department and General Medicine Department for the management of his joint pains and for further systemic evaluation and treatment.

Discussion

AKU is an autosomal recessive genetic disease. It was first described by Sir Archibald Garrod as an “inborn error of metabolism” in 1901 in London, UK.[1] The defects have been mapped to chromosome 3, between regions 3q21-q23. It is an inborn error of metabolism of phenylalanine and tyrosine and is characterized by the inability to metabolize HGA. The HGD enzyme catalyzes the conversion of HGA into maleylacetoacetic acid.[2,3] Therefore, AKU results in the accumulation of HGA at 2000 times the normal rate. Upon contact with air, HGA is oxidized to form a pigment-like polymeric material responsible for the black color of standing urine. Although HGA blood levels are kept very low through rapid kidney clearance, over time HGA is deposited in cartilage throughout the body and is converted to the pigment-like polymer through an enzyme-mediated reaction that occurs chiefly in collagenous tissues. As the polymer accumulates within cartilage, the normally transparent tissues become slate blue and this is not seen until adulthood. The earliest sign of the disorder is the tendency for diapers to stain black. Throughout childhood and most of early adulthood, an asymptomatic, slowly progressive deposition of pigment-like polymer material into collagenous tissues occurs. In the fourth decade of life, external signs of pigment deposition, called ochronosis, begin to appear. Life expectancy is normal; however, associated morbidity can be significant. Early involvement of the intervertebral discs at the thoracic and lumbar levels is very common, occurring in approximately 50% of affected individuals. Typically, significant back pain begins from 30 years of age. The large joints (knee, shoulder, and hip) are very frequently involved.[4,5] Achilles tendon involvement is also common and may result in tearing. Involvement of the aortic leaflets, mitral valve leaflets, or both is common, and calcifications of the coronary arteries occur in one-half of all patients before 60 years of age. The distribution of this disease is equal in males and females. It is an autosomal recessive or autosomal dominant trait. Males tend to have an earlier onset of arthritic symptoms with a greater degree of severity than females; slate blue or gray discoloration may be found in the sclerae or ear cartilage.[6]

Ocular manifestations include symmetric brown scleral pigmentation. There are four main types of appearance which may also occur in combination: (1) small “vermiform”[6] or “tube-like” pigment deposits, (2) brown pinguecula-like, (3) dot-like,[7] or (4) laminar structures. Dilated conjunctival vessels can be present and they supply the pigmented areas on the conjunctiva.

Treatment

Medical therapy is used to ameliorate the rate of pigment deposition. Reduction of phenylalanine and tyrosine has reportedly reduced HGA excretion. Vitamin C, as much as 1 g/day, is recommended for older children and adults. The mild antioxidant nature of ascorbic acid helps retard the process of conversion of homogentisate to the polymeric material that is deposited in cartilaginous tissues.[8,9] Limited use of nitisinone, an inhibitor of the enzyme 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase, which mediates formation of HGA, has been reported. Reduction of phenylalanine and tyrosine reportedly reduced HGA excretion in the urine of a child.

We performed a Medline search with keywords “alkaptonuria,” “ochronosis,” “ocular manifestations of alkaptonuria/ochronosis,” and various combinations. To the best of our knowledge, bilateral epiretinal membrane has not been reported previously in AKU or ocular ochronosis.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Garrod AE. The incidence of alkaptonuria: A study in chemical individuality 1902 [classical article] Yale J Biol Med. 2002;75:221–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lodh M, Kerketta JA. Early diagnosis of co-existent ß-thalassemia and alkaptonuria. Indian J Hum Genet. 2013;19:259–61. doi: 10.4103/0971-6866.116104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zatkova A, Sedlackova T, Radvansky J, Polakova H, Nemethova M, Aquaron R, et al. Identification of 11 novel homogentisate 1,2 dioxygenase variants in alkaptonuria patients and establishment of a novel LOVD-based HGD mutation database. JIMD Rep. 2012;4:55–65. doi: 10.1007/8904_2011_68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Brien W, La Du BN, Bunim JJ. Biochemical, pathological and clinical aspects of alkaptonuria, ochronosis and ochronotic arthropathy: Review of the world literature. Am J Med. 1963;34:813–38. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perry MB, Suwannarat P, Furst GP, Gahl WA, Gerber LH. Musculoskeletal findings and disability in alkaptonuria. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2280–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hackethal U, Busse H, Seitz HM, Gerding H. Vermiform conjunctival structures. Ophthalmologe. 2004;101:626–8. doi: 10.1007/s00347-003-0865-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felbor U, Mutsch Y, Grehn F, Müller CR, Kress W. Ocular ochronosis in alkaptonuria patients carrying mutations in the homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase gene. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:680–3. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.6.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anikster Y, Nyhan WL, Gahl WA. NTBC and alkaptonuria. AmJ Hum Genet. 1998;63:920–1. doi: 10.1086/302027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayatepek E, Kallas K, Anninos A, Müller E. Effects of ascorbic acid and low-protein diet in alkaptonuria. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157:867–8. doi: 10.1007/s004310050956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]