Abstract

Background

Angiostrongylus vasorum is the causative agent of canine angiostrongylosis, a severe snail-borne disease of dogs. Red foxes are important natural reservoirs of infection, and surveys of foxes provide a more objective picture of the parasite distribution. Our aim was to investigate the possibility of the presence of A. vasorum in red foxes from the western part of Romania and to analyse the risk factors related to the sex, age and geographic origin of the foxes. Between July 2016 and April 2017, 567 hunted red foxes from 10 counties of western Romania were examined by necropsy for the presence of lungworms.

Results

Overall, the infection with A. vasorum has been found in 24 red foxes (4.2%) originating in four counties (Mureș, Hunedoara, Sălaj and Cluj). There was no significant difference between the prevalence in males and females, between juveniles and adults and between counties.

Conclusions

This is the first report of autochthonous infections of A. vasorum in Romania, showing a relatively low prevalence and extending eastwards the known distributional range of this parasite in Europe. The presence of autochthonous cases in domestic dogs in Romania remains to be confirmed by further studies.

Keywords: Angiostrongylus vasorum, Romania, Red fox, Vulpes vulpes

Background

Angiostrongylus vasorum, or the French heartworm, is the causative agent of canine angiostrongylosis, a severe snail-borne disease of dogs, with an almost worldwide distribution (Europe, South America, North America and Africa) [1]. Since its description in France [2], the parasite has been found in several European countries [3], being nowadays considered an emerging parasite [4]. Despite its wide geographical distribution, the presence of A. vasorum throughout its range seems to be patchy, with endemic disease foci surrounded by areas with sporadic cases [3]. Although during the last years the research on this parasite has intensified, the actual distribution is considered unknown [5], mainly because of unreported cases and limited awareness of clinicians [4]. In the last two decades, the presence of A. vasorum has been reported for the first time in several European countries (Table 1).

Table 1.

Year of the first country report of autochthonous cases of Angiostrongylus vasorum in Europe in the last two decades

| Year of the first report of autochthonous casesa | Country | Host species | Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Croatia | Red fox | Necropsy | [39] |

| 2003 | Germany | Domestic dog | Baermann | [25] |

| 2003 | Hungary | Red fox | Necropsy | [40] |

| 2003 | Sweden | Domestic dog | Necropsy | [41] |

| 2004 | Iceland | Domestic dog | Baermann | [42] |

| 2007 | Greece | Domestic dog | Sedimentation | [43] |

| 2008 | Netherlands | Domestic dog | Baermann | [44] |

| 2013 | Poland | Domestic dog | ELISA | [45] |

| 2013 | Slovakia | Domestic dog | Baermann | [46] |

| 2014 | Serbia | Domestic dog | Baermann | [47] |

| 2014 | Czech Republic | Domestic dog | Baermann | [48] |

| 2015 | Belgium | Domestic dog | Necropsy, PCR | [49] |

| 2015 | Albania | Domestic dog | Baermann | [50] |

| 2017 | Romania | Red fox | Necropsy | present study |

aOnly the countries where the first report of A. vasorum was published in the last 20 years are included. Countries where the parasite was reported before, are not included. This is to highlight the increased interest and/or possible emergence of A. vasorum

Red foxes are known to be important natural reservoirs of parasitic infection for domestic animals and humans across their distribution range [6]. In Romania, red foxes have been demonstrated as carriers of a wide range of parasites: Trichinella spp. [7], Echinococcus multilocularis [8], ticks and tick-borne bacteria [9–12], Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum [13], Eucoleus aerophilus [14] and Hepatozoon canis [15].

The spatial model suggested by Morgan et al. [5] includes the western part of Romania as a risk area for the presence of A. vasorum, but so far there are no confirmed autochthonous cases. Our aim was to investigate the possibility of the presence of A. vasorum in red foxes from the western part of Romania and to analyse the risk factors related to the sex, age and geographic origin of the foxes.

Methods

Samples

Between July 2016 and April 2017, 567 red foxes, were collected by hunters in 10 counties (Table 2) (through the County Veterinary Authority) of Romania. For safety reasons, only foxes which were confirmed as negative for rabies were examined. Prior to necropsy, all foxes have been deep frozen. During the necropsy, the right heart and pulmonary arteries were opened and carefully checked for the presence of parasites. All nematodes were collected in 70% ethanol and morphologically identified [16]. For each fox, the location, sex and age (young, less than one-year-old; and adult, more than one-year-old, according to Harris [17]) was noted.

Table 2.

Presence of Angiostrongylus vasorum in red foxes, Vulpes vulpes, from western Romania

| County | Total | Males | Females | Adults | Young | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | + | n | + | n | + | n | + | n | + | |

| Arad | 30 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 19 | 0 |

| Bihor | 41 | 0 | 28 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Caraș-Severin | 18 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Cluj | 33 | 1 (3.0%) | 16 | 0 | 17 | 1 (5.9%) | 24 | 1 (4.2%) | 9 | 0 |

| Gorj | 99 | 0 | 62 | 0 | 37 | 0 | 70 | 0 | 29 | 0 |

| Hunedoara | 61 | 5 (8.2%) | 30 | 5 (16.7%) | 31 | 0 | 45 | 3 (6.7%) | 16 | 2 (12.5%) |

| Maramureș | 23 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 11 | 0 |

| Mureș | 156 | 17 (10.9%) | 81 | 8 (9.9%) | 75 | 9 (12.0%) | 108 | 8 (7.4%) | 48 | 9 (18.8%) |

| Sălaj | 25 | 1 (4.0%) | 16 | 1 (6.3%) | 9 | 0 | 12 | 1 (8.3%) | 13 | 0 |

| Satu-Mare | 82 | 0 | 52 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 47 | 0 | 35 | 0 |

| Total | 567 | 24 (4.2%) | 322 | 14 (4.3%) | 245 | 10 (4.1%) | 378 | 13 (3.4%) | 189 | 11 (5.8%) |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using EpiInfo™ 7 software (CDC, USA). The mean intensity and prevalence of infection and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated. The differences among positive groups were assessed by means of chi-square testing and were considered significant if P-values were lower than 0.05.

Molecular identification

Genomic DNA was extracted from 10 adult females using a commercial kit (Isolate II Genomic DNA Kit, Bioline, London, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each nematode, PCR amplifications of a partial mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1, ∼700 bp) gene and the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2, ∼500 bp) of the rRNA gene, were performed according to literature [18, 19]. Amplicons were purified using a commercial kit (Isolate II PCR and Gel Kit, Bioline, London, UK) and sequenced (performed by Macrogen Europe, Amsterdam). The newly generated sequences were compared to those available in the GenBank by Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) analysis.

Results

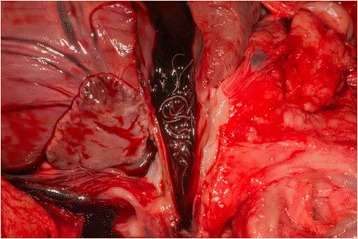

All nematodes collected form the pulmonary arteries and right ventricle (Fig. 1) of foxes were identified based on morphological criteria as A. vasorum. Ten nematodes were randomly selected for further molecular confirmation. BLAST analysis revealed a 100% identity to other A. vasorum sequences (GQ982791, GQ982741 for cox1; GU045374, EU627596, EU915248 for ITS2).

Fig. 1.

Angiostrongylus vasorum in the pulmonary artery of a red fox, Vulpes vulpes in Romania

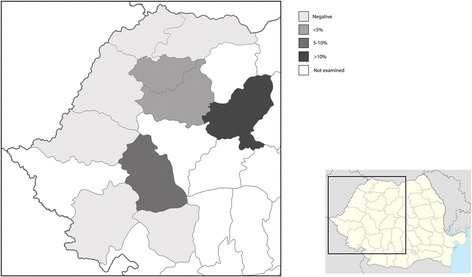

Out of the 567 red foxes examined, 24 (4.2%; 95% CI: 2.86–6.22) were positive for A. vasorum infection (Table 2). Angiostrongylus vasorum was found in four counties (Fig. 2), with a prevalence ranging between 3.0 (95% CI: 0.08–15.76) and 10.9% (95% CI: 6.52–16.98). There was no significant difference between the prevalence in males and females (χ 2 = 0, df = 1, P = 1), between juveniles and adults (χ 2 = 1.22, df = 1, P = 0.26) and between counties (χ 2 = 3.03, df = 3, P = 0.38).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence map of A. vasorum in red foxes in western Romania

The intensity of infection varied between 1 and 57 nematodes per positive animal (mean intensity 11.8). The mean intensity in adult foxes was 10.6 and in juveniles 14.7. The mean intensity in female foxes was 10.0 in males and 11.5 in females. The average sex ratio (M:F) in the parasite infrapopulation was 0.32 (range 0.8–1.5).

Discussion

In general, foxes are considered to be important reservoirs of infection with A. vasorum for domestic dogs [20, 21]. A study in Canada showed that the infection in foxes has established long before the first canine cases were recorded [22]. Most studies indicate that, in general, the local prevalence in foxes is higher compared to dogs [23]. Furthermore, Helm et al. [4] suggested that surveys of foxes provide a more objective picture of the parasite distribution. Although foxes are essential in the maintenance of infection foci, dogs are considered to have the main role in the geographical spreading of the parasite, mainly due to the more intense movements (i.e. importation, tourism) [4]. Interestingly, despite existing parasitological surveys in foxes, most of the first country reports from the last two decades in Europe, originate in domestic dogs (Table 1). The only exceptions are countries form the margin of the distribution area of A. vasorum (Croatia, Hungary, Romania), where foxes were found infected before dogs (Table 1).

The recorded prevalence of infection with A. vasorum in red foxes in Europe is between 5.0 and 78.2% [4, 24] but there is a high variation across different regions. The average prevalence in our study was 4.2%, at the lower limit of the overall range in Europe. This is somehow expected, as Romania is at the eastern margin of the distributional range of A. vasorum. Similar prevalence rates were recorded in foxes in Hungary (5.0%) [25], Poland (5.2–5.3%) [26] and Portugal (7.1%) [27]. However, in foxes from the endemic areas of Europe the prevalence is generally higher: UK (18.3%) [28], Spain (33.3%) [29], Ireland (49.3%) [30], Denmark (48.6%) [31] and Italy (78.2%) [24].

In our study, young foxes (less than one-year-old) were more commonly infected with A. vasorum than adults, but with no statistical significant differences. However, several studies from highly endemic areas have shown an opposite trend, with higher prevalence in adult foxes [31]. In other studies from less endemic areas, there was no significant difference between the prevalence in adult and young foxes [32]. In an experimental infection study with A. vasorum in red foxes, Webster et al. [33] proved that adult animals are more resistant than juveniles. The higher prevalence in young animals has been documented on several occasions also in dogs (as reviewed by Helm et al. [4]). Several hypotheses have been suggested to explain this pattern, such as the inquisitive nature of young animals making them more likely to be exposed to snails [34], age-related differences in dietary and scavenging behaviour [4] or an increased acquired immunity with age [33]. There is no consistent opinion on the gender predisposition neither in dogs, nor in foxes, and most reports failed to find increased rates of infection in males or females [4].

Interestingly, from the 10 examined counties, the infection with A. vasorum in foxes has been found only in four. The counties located at the western border of Romania (i.e. Satu-Mare, Bihor, Arad), despite a relatively high number of foxes examined, were all negative. All these counties have a predominantly lowland elevation (< 130 m above sea level, masl). The infection was present only in counties with predominant altitudes between 400 and 600 masl. The only exception was Gorj County (predominantly hilly), where no cases were found despite the high number of foxes examined. The absence of A. vasorum in Maramureș and Caraș-Severin counties might be related also to the low number of examined samples. Previously, larval stages resembling A. vasorum have been found in dogs from the western part of Romania (Timiș County). However, no details on the parasite identification, molecular identity or travel history of the dogs have been provided [35] so the autochthonous nature of these cases remains to be confirmed. Recently, two other species of the genus have been documented in Romania: A. chabaudi in wildcats [36] and A. daskalovi in badgers [37]. Recently, a large-scale serological study in red foxes from Switzerland suggested that foxes may have an increased parasite tolerance, allowing the long-term survival of A. vasorum in these canids. This might explain the importance of red foxes in the epidemiology of A. vasorum across Europe [38].

Although this is the first report of autochthonous A. vasorum infection in Romania, the absence of this parasite so far is probably related to a poor surveillance of wild canids and a lack of awareness among small animal clinicians rather than representing a situation of an emerging disease. The clinical signs in domestic dogs are characteristic, consisting most commonly in respiratory signs (coughing, dyspnoea, tachypnea, gagging) and coagulopathies (haemorrhagic diatheses) [4]. However, they are not pathognomonic, and a confirmatory test (usually larvoscopy or serology) is needed [4]. It is known that client and veterinarian awareness on canine angiostrongylosis is poor in non-endemic areas [4] and this might result in significant underdiagnosis. This is why, the confirmation of A. vasorum in foxes in Romania, opens new differential diagnostic opportunities in the canine medicine.

Conclusions

This is the first report of autochthonous A. vasorum infection in Romania, showing a relatively low prevalence and extending eastwards the known distributional range of this parasites in Europe. The presence of autochthonous cases in domestic dogs in Romania remains to be confirmed by further studies.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the county laboratories of the National Veterinary and Food Safety Authority in Arad, Bihor, Caraș-Severin, Cluj, Gorj, Hunedoara, Maramureș, Mureș, Sălaj, and Satu-Mare for their full and unconditioned support in providing the samples.

Funding

The samples were collected for multiple purposes beyond the pure aim of the current manuscript using funds from the UEFISCDI project TE298/2015.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

GD performed necropsies, identified and counted the nematodes and wrote the manuscript. CMG performed necropsies, identified the nematodes and coordinated the study. AMI performed necropsies, molecular analysis and statistics. ADV, IAM and AAD performed necropsies. GDA, IM and AD essentially contributed to sample collection. VC critically revised the manuscript and coordinated the study. ADM essentially contributed to sample collection, critically revised the manuscript and coordinated the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Georgiana Deak, Email: georgiana.deak@usamvcluj.ro.

Călin M. Gherman, Email: calin.gherman@usamvcluj.ro

Angela M. Ionică, Email: ionica.angela@usamvcluj.ro

Alexandru D. Vezendan, Email: punk2509@gmail.com

Gianluca D’Amico, Email: gianluca.damico@usamvcluj.ro.

Ioana A. Matei, Email: matei.ioana@usamvcluj.ro

Aikaterini A. Daskalaki, Email: katerina.daskalaki@usamvcluj.ro

Ionuț Marian, Email: klis87ionut@yahoo.com.

Aurel Damian, Email: damian56aurel@yahoo.com.

Vasile Cozma, Email: cozmavasile@yahoo.com.

Andrei D. Mihalca, Email: amihalca@usamvcluj.ro

References

- 1.Ferdushy T, Hasan MT. Angiostrongylus vasorum: the “French heartworm”. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:765–71. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baillet CC. Helminthes. Nouv Diet Prat Med Vét. 1866;8:519–687. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgan E, Shaw S. Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in dogs: continuing spread and developments in diagnosis and treatment. J Small Anim Pract. 2010;51:616–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2010.01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helm JR, Morgan ER, Jackson MW, Wotton P, Bell R. Canine angiostrongylosis: an emerging disease in Europe. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2010;20:98–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-4431.2009.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan ER, Jefferies R, Krajewski M, Ward P, Shaw SE. Canine pulmonary angiostrongylosis: the influence of climate on parasite distribution. Parasitol Int. 2009;58:406–410. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okulewicz A, Hildebrand J, Okulewicz J, Perec A. Red fox (Vulpes vulpes) as reservoir of parasites and source of zoonosis. Wiad Parazytol. 2005;51:125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaga R, Gherman C, Cozma V, Zocevic A, Pozio E, Boireau P. Trichinella species circulating among wild and domestic animals in Romania. Vet Parasitol. 2009;159:218–221. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sikó SB, Deplazes P, Ceica C, Tivadar CS, Bogolin I, Popescu S, Cozma V. Echinococcus multilocularis in south-eastern Europe (Romania) Parasitol Res. 2011;108:1093–1097. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumitrache MO, D'Amico G, Matei IA, Ionică A, Gherman CM, Barabási SS, et al. Ixodid ticks in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Romania. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7(Suppl 1):P1. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-S1-P1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumitrache MO, Matei IA, Ionică AM, Kalmár Z, D'Amico G, Sikó-Barabási SS, et al. Molecular detection of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Romania. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:514. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1130-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Amico G, Juránková J, Tăbăran FA, Frgelecová L, Forejtek P, Matei IA, et al. Occurrence of ticks in the subcutaneous tissue of red foxes, Vulpes vulpes in Czech Republic and Romania. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2017;8:309–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Amico G, Dumitrache MO, Matei IA, Ionică AM, Gherman CM, Sándor AD, et al. Ixodid ticks parasitizing wild carnivores in Romania. Exp Appl Acarol. 2017;71:139–149. doi: 10.1007/s10493-017-0108-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Şuteu O, Mihalca AD, Paştiu AI, Györke A, Matei IA, Ionică A, et al. Red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Romania are carriers of Toxoplasma gondii but not Neospora caninum. J Wildl Dis. 2014;50:713–716. doi: 10.7589/2013-07-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Cesare A, Otranto D, Latrofa MS, Veronesi F, Perrucci S, Lalosevic D, et al. Genetic variability of Eucoleus aerophilus from domestic and wild hosts. Res Vet Sci. 2014;96:512–515. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitková B, Qablan MA, Mihalca AD, Modrý D. Questing for the identity of Hepatozoon in foxes. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7(Suppl 1):O23. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-S1-O23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costa JO, de Araujo Costa HM, Guimaraes MP. Redescription of Angiostrongylus vasorum (Baillet, 1866) and systematic revision of species assigned to the genera Angiostrongylus Kamensky, 1905 and Angiocaulus Schulz, 1951. Rev Méd Vét. 2003;154:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris S. Age determination in the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) - an evaluation of technique efficiency as applied to a sample of suburban foxes. J Zool. 1978;184:91–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1978.tb03268.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasser RB, Chilton NB, Hoste H, Beveridge I. Rapid sequencing of rDNA from single worms and eggs of parasitic helminths. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2525–2526. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.10.2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caldeira RL, Carvalho OS, Mendonça CL, Graeff-Teixeira C, Silva MC, Ben R, et al. Molecular differentiation of Angiostrongylus costaricensis, A. cantonensis, and A. vasorum by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:1039–1043. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762003000800011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolt G, Monrad J, Henriksen P, Dietz HH, Koch J, Bindseil E, Jensen AL. The fox (Vulpes vulpes) as a reservoir for canine angiostrongylosis in Denmark. Field survey and experimental infections. Acta Vet Scand. 1992;33:357–362. doi: 10.1186/BF03547302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan ER, Shaw SE, Brennan SF, De Waal TD, Jones BR, Mulcahy G. Angiostrongylus vasorum: a real heartbreaker. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:49–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Bourgue A, Conboy G, Miller L, Whitney H, Ralhan S. Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in 2 dogs from Newfoundland. Can Vet J. 2002;43:876–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Koch J, Willesen JL. Canine pulmonary angiostrongylosis: an update. Vet J. 2009;179:348–359. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magi M, Guardone L, Prati MC, Mignone W, Macchioni F. Extraintestinal nematodes of the red fox Vulpes vulpes in north-west Italy. J Helminthol. 2015;89:506–511. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X1400025X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barutzki D, Schaper R. Endoparasites in dogs and cats in Germany 1999–2002. Parasitol Res. 2003;90(Suppl 3):148–150. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0922-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demiaszkiewicz AW, Pyziel AM, Kuligowska I, Lachowicz J. The first report of Angiostrongylus vasorum (Nematoda; Metastrongyloidea) in Poland, in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) Acta Parasitol. 2014;59:758–762. doi: 10.2478/s11686-014-0290-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Figueiredo A, Oliveira L, Madeira de Carvalho L, Fonseca C, Torres RT. Parasite species of the endangered Iberian wolf (Canis lupus signatus) and a sympatric widespread carnivore. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2016;5:164–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor CS, Garcia Gato R, Learmount J, Aziz NA. Increased prevalence and geographic spread of the cardiopulmonary nematode Angiostrongylus vasorum in fox populations in great Britain. Parasitology. 2015;9:1190–1195. doi: 10.1017/S0031182015000463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerrikagoitia X, Barral M, Juste RA. Angiostrongylus species in wild carnivores in the Iberian Peninsula. Vet Parasitol. 2010;174:175–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Houpin E, McCarthy G, Ferrand M, De Waal T, O'Neill EJ, Zintl A. Comparison of three methods for the detection of Angiostrongylus vasorum in the final host. Vet Parasitol. 2016;220:54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saeed I, Maddox-Hyttel C, Monrad J, Kapel CM. Helminths of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Denmark. Vet Parasitol. 2006;139:168–179. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan ER, Tomlinson A, Hunter S, Nichols T, Roberts E, Fox MT, Taylor MA. Angiostrongylus vasorum and Eucoleus aerophilus in foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in great Britain. Vet Parasitol. 2008;154:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Webster P, Monrad J, Kapel CM, Kristensen AT, Jensen AL, Thamsborg SM. The effect of host age and inoculation dose on infection dynamics of Angiostrongylus vasorum in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:4. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1940-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chapman PS, Boag AK, Guitian J, Boswood A. Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in 23 dogs (1999–2002) J Small Anim Pract. 2004;45:435–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2004.tb00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ilie MS, Imre M, Imre K, Hora FȘ, Dărăbuș G, Jurca AO, et al. Prevalence of Angiostrongylus vasorum infestation in dogs from western Romania - preliminary results. Lucr Științ Med Vet. 2016;49(3):78–81. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gherman CM, Ionică AM, D'Amico G, Otranto D, Mihalca AD. Angiostrongylus chabaudi (Biocca, 1957) in wildcat (Felis silvestris silvestris, S) from Romania. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:2511–2517. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-5032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gherman CM, Deak G, Matei IA, Ionică AM, D'Amico G, Taulescu M, et al. A rare cardiopulmonary parasite of the European badger, Meles meles: first description of the larvae, ultrastructure, pathological changes and molecular identification of Angiostrongylus daskalovi Janchev & Genov 1988. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:423. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1718-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gillis-Germitsch N, Kapel CMO, Thamsborg SM, Deplazes P, Schnyder M. Host-specific serological response to Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes): implications for parasite epidemiology. Parasitology. 2017; (In press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Rajković-Janje R, Marinculić A, Bosnić S, Benić M, VinkoviĆ B, Mihaljević Ž. Prevalence and seasonal distribution of helminth parasites in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from the Zagreb County (Croatia) Z Jagdwiss. 2002;8:151–160. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sréter T, Széll Z, Marucci G, Pozio E, Varga I. Extraintestinal nematode infections of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Hungary. Vet Parasitol. 2003;115:329–334. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(03)00217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ablad B, Christensson D, Lind EO, Agren E, Morner T. Angiostrongylus vasorum etablerad i Sverige. Svensk Veterinartidning. 2003;55:11–6.

- 42.Conboy G. Natural infections of Crenosoma vulpis and Angiostrongylus vasorum in dogs in Atlantic Canada and their treatment with milbemycin oxime. Vet Rec. 2004;155:16–18. doi: 10.1136/vr.155.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papazahariadou M, Founta A, Papadopoulos E, Chliounakis S, Antoniadou-Sotiriadou K, Theodorides Y. Gastrointestinal parasites of shepherd and hunting dogs in the Serres prefecture, northern Greece. Vet Parasitol. 2007;148:170–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.van Doorn DC, van de Sande AH, Nijsse ER, Eysker M, Ploeger HW. Autochthonous Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in dogs in the Netherlands. Vet Parasitol. 2009;162:163–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Schnyder M, Schaper R, Pantchev N, Kowalska D, Szwedko A, Deplazes P. Serological detection of circulating Angiostrongylus vasorum antigen-and parasite-specific antibodies in dogs from Poland. Parasitol Res. 2013;112(Suppl 1):109–117. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hurníková Z, Miterpáková M, Mandelík R. First autochthonous case of canine Angiostrongylus vasorum in Slovakia. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:3505–3508. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3532-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simin S, Kosić LS, Kuruca L, Pavlović I, Savović M, Lalošević V. Moving the boundaries to the south-east: First record of autochthonous Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in a dog in Vojvodina province, northern Serbia. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Hajnalová M, Juránková J, Svobodová V. Dog's lungworm disease in the Czech Republic. Fourth European Dirofilaria and Angiostrongylus days (FEDAD), Budapest, Hungary; 2014. p. 103.

- 49.Jolly S, Poncelet L, Lempereur L, Caron Y, Bayrou C, Cassart D, et al. First report of a fatal autochthonous canine Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in Belgium. Parasitol Int. 2015;64:97–99. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shukullari E, Hamel D, Rapti D, Pfister K, Visser M, Winter R, Rehbein S. Parasites and vector-borne diseases in client-owned dogs in Albania. Intestinal and pulmonary endoparasite infections. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:4579–4590. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4704-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.