Abstract

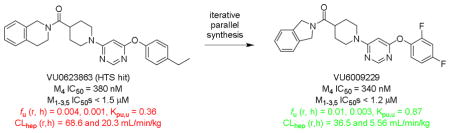

This Letter describes the synthesis and structure activity relationship (SAR) studies of structurally novel M4 antagonists, based on a 4,6-disubstituted core, identified from a high-throughput screening campaign. A multi-dimensional optimization effort enhanced potency at both human and rat M4 (IC50s < 300 nM), with no substantial species differences noted. Moreover, CNS penetration proved attractive for this series (brain:plasma Kp,uu = 0.87), while other DMPK attributes were addressed in the course of the optimization effort, providing low in vivo clearance in rat (CLp = 5.37 mL/min/kg). Surprisingly, this series displayed pan-muscarinic antagonist activity across M1–5, despite the absence of the prototypical basic or quaternary amine moiety, thus offering a new chemotype from which to develop a next generation of pan-muscarinic antagonist agents.

Keywords: pyrimidine, muscarinic acetylcholine receptor, pan-antagonist, DMPK, Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR)

Graphical Abstract

The muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) are members of the class A family of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which modulate the activity of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Currently, five mAChR subtypes (M1–M5) have been characterized. M1, M3 and M5 are Gq-coupled, and activate phospholipase C and calcium mobilization. M2 and M4 are coupled to Gi/o, and thus inhibit the actions of adenylyl cyclase. The mAChRs are distributed throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems, where they modulate a wide variety of neuronal and autocrine functions relating to memory, nociception, gastrointestinal function, and many others. The development of therapeutics targeting the mAChRs is therefore widely pursued, and such agents have the potential to be useful for a number of different pathologies.1,2

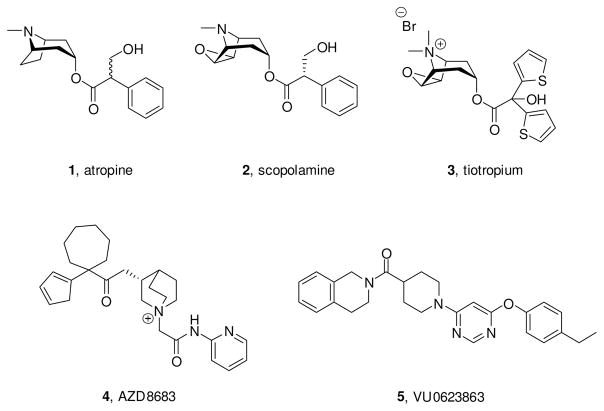

The majority of known muscarinic antagonists such as atropine (1) and the anti-emetic scopolamine (2) (Figure 1) are non-selective across the five receptor subtypes (pan-muscarinic antagonists). Other muscarinic antagonists include tiotropium bromide (3), a quaternary ammonium salt currently used for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),3 and AZD8683 (4), an M3-preferring antagonist with a long duration of action and reduced side effect profile compared to tiotropium (Figure 1).4 Muscarinic antagonists are also used to treat overactive bladder and have shown promise for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).5–7

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of known muscarinic antagonists 1–4, and the newly identified hit 5 from an M4 antagonist high-throughput screen.

Since the M4 receptor subtype is co-localized with dopaminergic D1 receptors in the striatum, M4 modulation has been identified as potentially playing a role in various movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and dystonia; hence, our interest in development of selective M4 antagonists.8–11 Development of agents that are selective for M4, or any of the individual mAChRs, has traditionally proven difficult due to the high sequence homology amongst the receptor subtypes.2 In an effort to identify structurally novel and selective M4 antagonist chemotypes, a high-throughput screen was performed, and we identified the 4,6-disubstituted pyrimidine 5 (Figure 1) as a putative lead. This result was exciting, as 5 (VU0623863) represents a novel muscarinic antagonist scaffold, and we surmised that the potential for selectivity across the mAChR subtypes was high (especially given the lack of the basic nitrogen found in other non-selective muscarinic scaffolds 1–4), as we have previously demonstrated for both M1 and M5.12–18

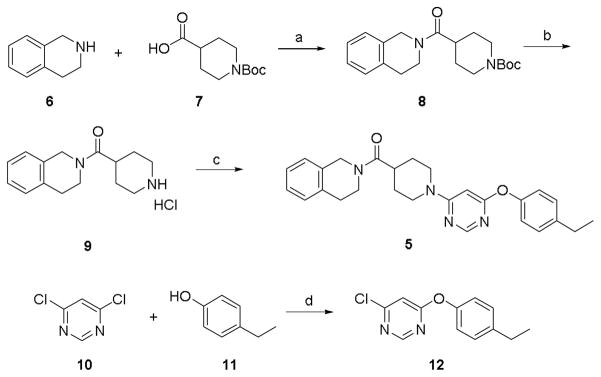

Compound 5 was resynthesized as shown in Scheme 1. Briefly, a HATU-mediated amide coupling between 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) 6 and N-Boc-isonipecotic acid 7 affords 8 in 91% yield. Subsequent Boc-deprotection yielded HCl salt 9 in quantitative yield. Nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) between 4,6-dichloropyrimidine 10 and 4-ethylphenol 11 provided 12, which could be coupled to 9 via microwave-assisted SNAr.19

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compound 5 and route for analog synthesis.a

aReagents and conditions: (a) HATU, DIPEA, DCM, 91%; (b) HCl, 1,4-dioxane, 99%; (c) 12, DIPEA, NMP, microwave, 150 °C, 59%; (d) K2CO3, DMF, 100 °C, 38%.

After resynthesis, compound 5 was found to have comparable, sub-micromolar potency at both human and rat M4 (IC50s of 380 nM (pIC50 = 6.46±0.09, 5.3±0.7 % ACh Min) and 590 nM (pIC50 = 6.25±0.10, 13.1±2.5 % ACh Min), respectively). Due to the unique and non-basic chemotype, we anticipated that this would be selective for M4, akin to our related efforts on M1 and M5.12–18 Surprisingly, the compound was also found to have substantial antagonist activity at all of the mAChRs (M1–3,5 IC50s < 1.5 μM), but was weakly M4-preferring (2- to 5-fold). We also assessed the DMPK profile of 5, and found it to be highly bound in plasma (fu,p lasma (r, h) = 0.004, 0.001), with a high rat brain:plasma Kp (1.45), but lower Kp,uu (0.36)(rat fu,brain = 0.001). Furthermore, the predicted hepatic clearance of 5 was near hepatic blood flow in both human and rat (CLhep = 20.3 and 68.6 mL/min/kg, respectively) based on CLint data from microsomes. Despite these blemishes, this scaffold was attractive from an academic standpoint to assess if either M4 selectivity could be improved or if a next generation pan-mAChR antagonist could be generated with favorable PK and CNS penetration to compliment 1–4.

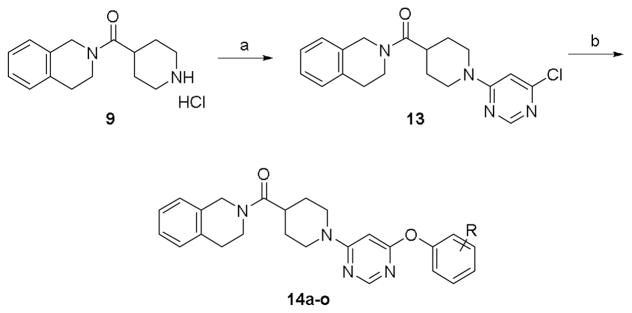

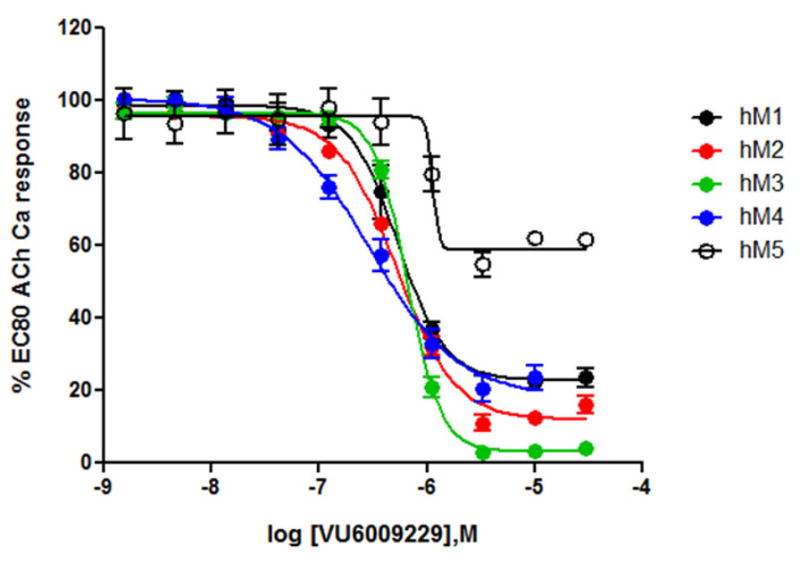

Toward these parallel goals, an SAR campaign focused around modifications to the eastern diaryl ether motif was pursued. In order to streamline the synthesis of these compounds for a more high-throughput approach, chloropyrimidine intermediate 13 was first synthesized from HCl salt 9 (Scheme 2). This intermediate could then be used as a platform for library synthesis, and a number of substituted phenols were coupled to 13 through microwave-assisted SNAr in moderate yields (14a–o).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of analogs 14.a

aReagents and conditions: (a) 4,6-dichloropyrimidine, DIPEA, DMF, 100 °C, 88%; (b) substituted phenol, Cs2CO3, NMP, microwave, 180 °C, 45–67%.

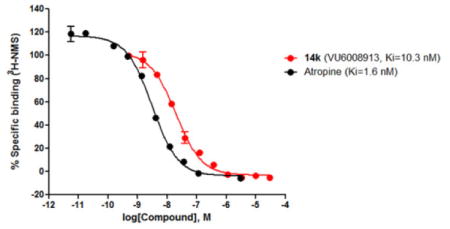

All analogs 14 were of comparable potency at rat M4 (IC50s within 2- to 3-fold, n = 1), and all were uniformly predicted to be highly cleared (predicted CLhep of ~18–20 mL/min/kg and ~60–68 mL/min/kg, for human and rat respectively). Similarly, SAR was rather ‘flat’ with little texture with respect to M4 inhibition, suggesting other areas of the molecule may be better targets for future optimization. However, analog 14g showed high brain distribution (rat Kp ~0.68, Kp,uu ~0.75), but its high clearance hindered any further advancement. Moreover, when evaluated in a [3H]-NMS binding assay with human M4 cell membranes, 14k (VU6008913) displaced the radioligand binding with a Ki of 10.3 nM (cf. to atropine, Ki = 1.6 nM),20 which translated into no mAChR selectivity (M1 IC50 = 250 nM, M2 IC50 = 330 nM, M3 IC50 = 380 nM, M5 IC50 = 510 nM, all n = 1 and <6% ACh Min). Similarly, other potent antagonists such as 14g (M1 IC50 = 322 nM, M2 IC50 = 384 nM, M3 IC50 = 404 nM, M5 IC50 = 732 nM, all n = 1 and <6% ACh Min) and 14h (M1 IC50 = 313 nM, M2 IC50 = 352 nM, M3 IC50 = 365 nM, M5 IC50 = 695 nM, all n = 1 and <6% ACh Min) were pan-mAChR antagonists. Thus, it became readily apparent that this series was not likely to afford selective M4 antagonists, but that the goal should instead focus on development of a next generation pan-mAChR antagonist with exceptional PK and CNS penetration to compliment 1–4.

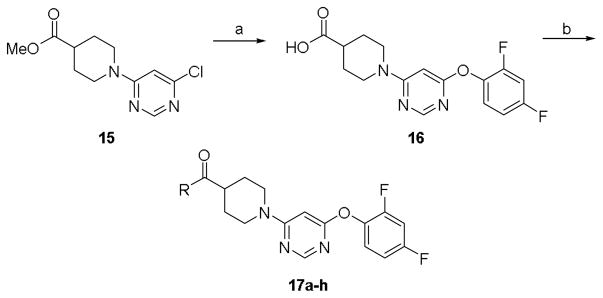

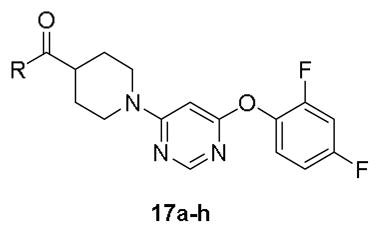

Due to a putative blockade of oxidative metabolism of the phenyl moiety via fluoro substitution, we next decided to hold the 2,4-difluoro phenylether eastern piece constant and explore an amide library to evaluate alternatives for the western THIQ moiety. Starting from commercially available methyl 1-(6-chloropyrimidin-4-yl)piperidine-4-carboxylate 15, a one-pot SNAr/methyl ester hydrolysis was performed under microwave irradiation to give carboxylic acid 16 in moderate yield, which could then be used for HATU-mediated amide couplings to give final analogs 17a–h (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of compounds 17a–h.a

aReagents and conditions: (a) 2,4-difluorophenol, Cs2CO3, NMP, microwave, 180 °C, 49%; (b) amine, HATU, DIPEA, DMF, 32–67%.

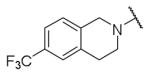

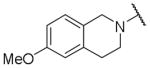

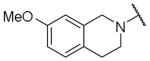

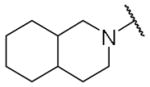

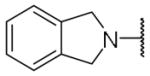

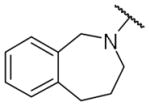

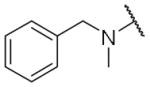

As shown in Table 2, SAR was steep with respect to replacements for the THIQ moiety. Benzyl amines such as 17g and 17h were inactive, as was a CF3-substituted THIQ, 17a. Electron-donating moieties, such as the regioisomeric OMe-substituted THIQ analogs 17b and 17c, retained M4 inhibitory activity, as did a fully saturated congener 17d. However, the isoindoline derivative 17e emerged as the most exciting analog. 17e was a potent antagonist at both human and rat M4 (hM4 IC50 = 340 nM, pIC50 = 6.49±0.06, 18.4±2.3% ACh Min and rM4 IC50 = 560 nM, pIC50 = 6.32±0.18, 42.7±3.2% ACh Min), but displayed partial antagonist activity.21,22 Moreover, 17e proved to also be a pan-mAChR antagonist (Figure 2). However, the disposition of 17e was superior to all other analogs 14 and 17 evaluated. 17e (VU6009229) displayed good CNS penetration (rat brain:plasma Kp = 0.67, Kp,uu = 0.87) and low to moderate predicted hepatic clearance (rat CLhep = 36.5 mL/min/kg and human CLhep = 5.56 mL/min/kg). A robust in vitro:in vivo correlation (IVIVC) was noted, with 17e displaying a low rat in vivo clearance (CLp = 5.37 mL/min/kg; predicted CLhep with inclusion of binding terms in the well-stirred model = 5.93 mL/min/kg) with a 3.7 hour elimination half-life and modest volume (Vss = 1.35 L/kg) in an IV cassette (0.2 mg/kg; n = 1) study. Thus, 17e emerged as a next generation pan-mAChR partial antagonist tool compound, with attractive in vivo rat PK and excellent CNS penetration, suitable for in vitro and in vivo studies.

Table 2.

Structures and mAChR activities of analogs 17a–h.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | hM4 IC50 (μM)a [% ACh Min ±SEM] | hM4 pIC50 (±SEM)a |

| 17a |

|

>10 | >5 |

| 17b |

|

0.58 [5.5±2.9] | 6.25±0.09 |

| 17c |

|

2.47 [11.8±1.5] | 5.62±0.08 |

| 17d |

|

0.41 [5.1±0.6] | 6.39±0.05 |

| 17e |

|

0.34 [18.4±2.3] | 6.49±0.06 |

| 17f |

|

1.04 [6.0±0.5] | 6.00±0.05 |

| 17g |

|

>10 | >5 |

| 17h |

|

>10 | >5 |

Mean of three independent determinations in a calcium mobilization assay using recombinant hM4-expressing Chinese hamster ovary cells co-transfected with chimeric Gqi5 in the presence of an ACh EC80.

Figure 2.

Concentration response curves (CRCs) for 17e (VU6009229) in calcium mobilization assays with recombinant hM1–5 Chinese hamster ovary cells (co-transfected with Gqi5) in the presence of an approximate EC80 of ACh. (M1 IC50 = 540 nM (18.2% ACh min), M2 IC50 = 520 nM (8.7% ACh min), M3 IC50 = 660 nM (2.3% ACh min), M5 IC50 = 1,130 nM (42.6% ACh min), all n = 1.

In summary, an M4 HTS campaign identified 5 as a novel M4 antagonist chemotype, that proved to lack mAChR subtype selectivity. Further optimization afforded 17e, a potent and highly CNS penetrant pan-mAChR antagonist with an attractive rat in vivo PK profile. Additionally, 17e and related analogs do not feature the prototypical tropane structure of classical muscarinic antagonists, nor a strong basic amine. Thus, these analogs represent a next generation of pan-mAChR antagonists that could serve as leads for the development of potential safer or differentiating anti-cholinergic agents. The expedient and straightforward synthesis of these analogs will allow us to further explore the requirements for muscarinic selectivity, as well as fine-tune the DMPK properties of this series.

Table 1.

Structures and mAChR activities of analogs 5, 14a–o.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | hM4 IC50 (μM)a [% ACh Min ±SEM] | hM4 pIC50 (±SEM)a |

| 5 | 4-Et | 0.38 [5.3±0.7] | 6.46±0.09 |

| 14a | H | 0.65 [2.7±0.3] | 6.21±0.09 |

| 14b | 4-Me | 0.31 [3.3±0.2] | 6.52±0.08 |

| 14c | 2-naphthyl | 0.71 [6.8±2.2] | 6.16±0.06 |

| 14d | 3,4-methylenedioxy | 0.51 [4.1±0.3] | 6.30±0.09 |

| 14e | 4-F | 0.24 [3.5±0.2] | 6.64±0.02 |

| 14f | 3-F | 0.31 [3.2±0.3] | 6.52±0.06 |

| 14g | 2-F | 0.13 [3.2±0.5] | 6.91±0.08 |

| 14h | 4-Cl | 0.14 [3.0±0.2] | 6.88±0.07 |

| 14i | 4-OMe | 0.46 [5.3±1.0] | 6.30±0.06 |

| 14j | 2,3-diF | 0.19 [3.1±0.1] | 6.77±0.15 |

| 14k | 2,4-diF | 0.10 | 7.00±0.08 |

| 14l | 2,5-diF | 0.08 [3.1±0.2] | 7.11±0.11 |

| 14m | 2,6-diF | 2.72 [7.0±0.9] | 5.57±0.05 |

| 14n | 2-F, 4-Cl | 0.15 [3.1±0.3] | 6.93±0.06 |

| 14o | 2,4-diCl | 0.27 [3.0±0.1] | 6.58±0.09 |

Mean of three independent determinations in a calcium mobilization assay using recombinant hM4-expressing Chinese hamster ovary cells co-transfected with chimeric Gqi5 in the presence of an ACh EC80.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH for funding via the NIH Roadmap Initiative 1X01 MH077607 (C.M.N.), the Molecular Libraries Probe Center Network (U54MH084659 to C.W.L.) and U01MH087965 (Vanderbilt NCDDG). We also thank William K. Warren, Jr. and the William K. Warren Foundation who funded the William K. Warren, Jr. Chair in Medicine (to C.W.L.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kruse AC, Kobilka B, Gautam D, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A, Wess J. Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors: Novel Opportunities for Drug Development. Nat Rev. 2014;13:549–560. doi: 10.1038/nrd4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conn PJ, Christopoulos A, Lindsley CW. Allosteric Modulators of GPCRs: A Novel Approach for the Treatment of CNS Disorders. Nat Rev. 2009;8:41–54. doi: 10.1038/nrd2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato M, Komamura K, Kitakaze M. Tiotropium, a Novel Muscarinic M3 Receptor Antagonist, Improved Symptoms of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Complicated by Chronic Heart Failure. Circ J. 2006;70:1658–1660. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mete A, Bowers K, Bull RJ, Coope H, Donald DK, Escott KJ, Ford R, Grime K, Mather A, Ray NC, Russell V. The Design of a Novel Series of Muscarinic Receptor Antagonists Leading to AZD8683, a Potential Inhaled Treatment for COPD. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:6248–6253. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.09.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callan MJ. Irritable Bowel Syndrome Neuropharmacology. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:S58–S67. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200207001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonda S, Katayama K, Fujio M, Sakashita H, Inaba K, Asano K, Akira T. 1,5-Benzodioxepin Derivatives as a Novel Class of Muscarinic M3 Receptor Antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:925–931. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitch CH, Brown TJ, Bymaster FP, Calligaro DO, Dieckman D, Merrit L, Peters SC, Quimby SJ, Shannon HE, Shipley LA, Ward JS, Hansen K, Olesen PH, Sauerberg P, Sheardown MJ, Swedberg MDB, Suzdak P, Greenwood B. Muscarinic Analgesics with Potent and Selective Effects on the Gastrointestinal Tract: Potential Application for the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Med Chem. 1997;40:538–546. doi: 10.1021/jm9602470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernard V, Normand E, Bloch B. Phenotypical Characterization of the Rat Striatal Neurons Expressing Muscarinic Receptor Genes. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3591–3600. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-09-03591.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Böhme TM, Augelli-Szafran CE, Hallak H, Pugsley T, Serpa K, Schwarz RD. Synthesis and Pharmacology of Benzoxazines as Highly Selective Antagonists at M4 Muscarinic Receptors. J Med Chem. 2002;45:3094–3102. doi: 10.1021/jm011116o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ztaou S, Maurice N, Camon J, Guiraudie-Capraz G, Kerkerian-Le Goff L, Beurrier C, Liberge M, Amalric M. Involvement of Striatal Cholinergic Interneurons and M1 and M4 Muscarinic Receptors in Motor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease. J Neurosci. 2016;36:9161–9172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0873-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eskow Jaunarajs KL, Bonsi P, Chesselet MF, Standaert DG, Pisani A. Striatal Cholinergic Dysfunction as a Unifying Theme in the Pathophysiology of Dystonia. Progress in Neurobiology. 2015;127–128:91–107. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheffler DJ, Williams R, Bridges TM, Lewis LM, Xiang Z, Zheng F, Kane AS, Byum NE, Jadhav S, Mock MM, Zheng F, Lewis LM, Jones CK, Niswender CM, Weaver CD, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:356–368. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.056531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melancon BJ, Utley TJ, Sevel C, Mattmann ME, Cheung YY, Bridges TM, Morrison RD, Sheffler DJ, Niswender CM, Daniels JS, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Wood MR. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:5035–5040. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gentry PR, Kokubo M, Bridges TM, Byun N, Cho HP, Smith E, Hodder PS, Niswender CM, Daniels JS, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Wood MR. J Med Chem. 2014;57:7804–7810. doi: 10.1021/jm500995y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurata H, Gentry PR, Kokubo M, Cho HP, Bridges TM, Niswender CM, Byers FW, Wood MR, Daniels JS, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25:690–694. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.11.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gentry PR, Kokubo M, Bridges TM, Cho HP, Smith E, Chase P, Hodder PS, Utley TJ, Rajapakse A, Byers F, Niswender CM, Morrison RD, Daniels JS, Wood MR, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:1677–1682. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geanes AR, Cho HP, Nance KD, McGowan KM, Conn PJ, Jones CK, Meiler J, Lindsley CW. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2016;26:4487–4491. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.07.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGowan KM, Nance KD, Cho HP, Bridges TM, Conn PJ, Jones CK, Lindsley CW. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.02.020. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.All reactions were carried out employing standard chemical techniques under inert atmosphere. Solvents used for extraction, washing, and chromatography were HPLC grade. All reagents were purchased from commercial sources and were used without further purification. Analytical HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1200 LCMS with UV detection at 215 nm and 254 nm along with ELSD detection and electrospray ionization, with all final compounds showing > 95% purity and a parent mass ion consistent with the desired structure. All NMR spectra were recorded on a 400 MHz Brüker AV-400 instrument. 1H chemical shifts are reported as δ values in ppm relative to the residual solvent peak (MeOD = 3.31, CDCl3 = 7.26). Data are reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (br = broad, s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet), coupling constant (Hz), and integration. 13C chemical shifts are reported as δ values in ppm relative to the residual solvent peak (MeOD = 49.0, CDCl3 = 77.16). Low resolution mass spectra were obtained on an Agilent 1200 LCMS with electrospray ionization, with a gradient of 5–95% MeCN in 0.1% TFA water over 1.5 min. Automated flash column chromatography was performed on an Isolera One by Biotage. Microwave synthesis was performed on an Initiator+ by Biotage. Preparative purification (RP-HPLC) of library compounds was performed on a Gilson 215 preparative LC system.Representative experimental for 5. (3,4-dihydroisoquinolinyl)methanone. N-Boc-isonipecotic acid 7 (2.0 g, 8.72 mmol) and 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline 6 (1.39 g, 10.5 mmol) were dissolved in DCM (50 mL), and DIPEA (3.04 mL, 17.4 mmol) was added, followed by HATU (3.98 g, 10.5 mmol). The resulting solution was stirred at r.t. overnight, after which time the reaction mixture was quenched with sat. NaHCO3, and extracted with DCM. Combined organic extracts were filtered through a phase separator and concentrated. Crude residue was purified by column chromatography (hex/EtOAc) to give product 8 as a yellow solid (2.73 g, 91%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.17 – 7.07 (m, 4H), 4.65 (s, 1H), 4.60 (s, 1H), 4.08 (br, 2H), 3.76 (br, 1H), 3.66 (t, J = 5.7, 1H), 2.86 – 2.64 (m, 5H), 1.75 – 1.58 (m, 4H), 1.39 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.43, 173.24, 154.68, 135.11, 133.85, 133.48, 132.53, 129.07, 128.29, 127.04, 126.70, 126.63, 126.55, 126.38, 125.96, 79.53, 47.35, 44.46, 43.07, 40.02, 39.03, 38.89, 29.82, 28.44, 28.39, 28.28. LCMS (215 nm) RT = 0.924 min (>98%); m/z 289.2 [M+H - t-butyl]. Compound 8 (2.73 g, 7.93 mmol) was dissolved in 1,4-dioxane (40 mL), and 4M HCl in dioxanes solution (40 mL) was then added dropwise. The resulting solution was stirred at r.t. for 1 h, after which time solvents were concentrated under reduced pressure, and the resulting white solid 9 was dried under vacuum and used without additional purification (2.21 g, 99%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.25 – 7.15 (m, 4H), 4.82 (s, 1H), 4.70 (s, 1H), 3.86 (t, J = 5.8, 1H), 3.80 (t, J = 6.0, 1H), 3.49 – 3.46 (m, 2H), 3.27 – 3.14 (m, 3H), 2.97 (t, J = 5.7, 1H), 2.86 (t, J = 5.9, 1H), 2.04 – 1.91 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 173.11, 172.93, 134.63, 134.18, 132.82, 132.76, 128.33, 128.06, 126.73, 126.43, 126.23, 126.13, 126.09, 125.89, 48.48, 46.92, 44.28, 43.14, 42.95, 40.41, 35.77, 35.60, 29.20, 27.82, 25.20, 25.08. LCMS (215 nm) RT = 0.527 min (>98%); m/z 245.2 [M+H]. 4-ethylphenol 11 (205 mg, 1.68 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (10 mL) and K2CO3 (471 mg, 3.36 mmol) was added. 4,6-dichloropyrimidine 10 (250 mg, 1.68 mmol) was then added. The resulting solution was stirred at 100 °C until complete. Reaction mixture was cooled to r.t., and diluted with H2O and DCM. Aqueous layer was extracted with DCM, and combined organic extracts were filtered through a phase separator and concentrated. Crude residue was purified by RP-HPLC. Fractions containing product were basified with sat. NaHCO3 and extracted with DCM. Solvents were concentrated to give product 12 as a brown oil (149 mg, 38%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.50 (s, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 8.1, 2H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.1, 2H), 6.80 (s, 1H), 2.60 (q, J = 7.6, 2H), 1.18 (t, J = 7.6, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.61, 161.94, 158.65, 149.88, 142.33, 129.36, 121.16, 107.76, 28.33, 15.47. LCMS (215 nm) RT = 0.958 min (>95%); m/z 235.2 [M+H]. Compound 9 (50.2 mg, 0.18 mmol), compound 12 (28 mg, 0.12 mmol) and DIPEA (0.042 mL, 0.24 mmol) were combined in a microwave vial, and NMP (1 mL) was added. The resulting solution was heated to 150 °C with microwave irradiation for 20 min, after which time crude residue was purified directly by RP-HPLC. Fractions containing product were basified with sat. NaHCO3, and extracted with 3:1 chloroform/IPA. Solvents were concentrated to give product 5 (as a white solid (31 mg, 59%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.23 (s, 1H), 7.16 – 7.09 (m, 6H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.0, 2H), 5.88 (br, 1H), 4.66 (s, 1H), 4.63 (s, 1H), 4.28 (br, 2H), 3.77 (t, J = 5.7, 1H), 3.69 (t, J = 5.7, 1H), 2.98 – 2.77 (m, 5H), 2.59 (q, J = 7.6, 2H), 1.82 – 1.76 (m, 4H), 1.18 (t, J = 7.5, 3H). LCMS (215 nm) RT = 0.955 min (>98%); m/z 443.2 [M+H].Representative experimental for 17e (VU6009229). (1-(6-(2,4-difluorophenoxy)pyrimidin-4-yl)piperidin-4-yl)(isoindolin-2-yl)methanone. methyl 1-(6-chloropyrimidin-4-yl)piperidine-4-carboxylate 15 (500 mg, 1.96 mmol), 2,4-difluorophenol (1.02 g, 7.82 mmol) and Cs2CO3 (2.56 g, 7.82 mmol) were combined in a microwave vial, and NMP (11 mL) was added. The resulting solution was heated to 180 °C with microwave irradiation for 20 min, after which time solids were removed by filtration, and crude residue was purified by RP-HPLC. Fractions containing product were extracted with 3:1 chloroform/IPA. Solvents were dried with MgSO4, filtered and concentrated to give product 16 as a brown, spongy solid (320 mg, 49%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.27 (s, 1H), 7.20 – 7.14 (m, 1H), 6.97 – 6.88 (m, 2H), 6.05 (s, 1H), 4.27 – 4.24 (m, 2H), 3.17 – 3.10 (m, 2H), 2.70 – 2.63 (m, 1H), 2.06 – 2.02 (m, 2H), 1.82 – 1.73 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 179.03, 169.60, 163.87, 161.28, 161.18, 158.82, 158.72, 157.72, 156.01, 155.89, 153.51, 153.38, 136.62, 124.63, 124.54, 111.68, 111.64, 111.45, 111.41, 105.68, 105.46, 105.41, 105.19, 85.88, 43.83, 40.68, 27.46 (multiple Cs coupled to F). LCMS (215 nm) RT = 0.764 min (>98%); m/z 336.2 [M+H]. Compound 16 (50 mg, 0.15 mmol) and isoindoline (0.028 mL, 0.22 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (2 mL), and DIPEA (0.13 mL, 0.75 mmol) and was stirred at r.t. for 1 h, after which time crude residue was purified directly by RP-HPLC. Fractions containing product were basified with sat. NaHCO3, and extracted with 3:1 chloroform/IPA. Organic extracts were filtered through a phase separator and concentrated to give product 17e as a light brown solid (42 mg, 65%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.26 (s, 1H), 7.32 – 7.27 (m, 4H), 7.20 – 7.14 (m, 1H), 6.96 – 6.87 (m, 2H), 6.09 (s, 1H), 4.93 (s, 2H), 4.82 (s, 2H), 4.48 – 4.41 (m, 2H), 3.10 – 3.03 (m, 2H), 2.83 – 2.75 (m, 1H), 1.93 – 1.88 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.19, 169.70, 163.99, 161.12, 161.02, 158.67, 158.57, 157.87, 156.02, 155.90, 153.52, 153.39, 136.74, 136.70, 136.62, 136.58, 136.54, 136.01, 128.10, 127.72, 124.64, 124.62, 124.54, 124.52, 123.22, 122.70, 111.55, 111.51, 111.32, 111.29, 105.56, 105.34, 105.29, 105.07, 85.94, 52.51, 52.47, 43.96, 40.47, 27.59 (multiple Cs coupled to F). LCMS (215 nm) RT = 0.950 min (>98%); m/z 437.2 [M+H]. 20.

-

20.

- 21.Rodriguez AL, Nong Yi, Sekaran NK, Alagille D, Tamagnan GD, Conn PJ. Mol Pharm. 2005;68:793. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.016139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma S, Kedrowski J, Rook JM, Smith JM, Jones CK, Rodriguez AL, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. J Med Chem. 2009;52:4103–4106. doi: 10.1021/jm900654c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]