Abstract

Breast cancer risks conferred by many germline missense variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, often referred to as variants of uncertain significance (VUS), have not been established. In this study, associations between 19 BRCA1 and 33 BRCA2 missense substitution variants and breast cancer risk were investigated through a breast cancer case control study using genotyping data from 38 studies of predominantly European ancestry (41,890 cases and 41,607 controls) and nine studies of Asian ancestry (6,269 cases and 6,624 controls). The BRCA2 c.9104A>C, p.Tyr3035Ser (OR=2.52, p=0.04) and BRCA1 c.5096G>A, p.Arg1699Gln (OR=4.29, p=0.009) variant were associated with moderately increased risks of breast cancer among Europeans, whereas BRCA2 c.7522G>A, p.Gly2508Ser (OR=2.68, p=0.004) and c.8187G>T, p.Lys2729Asn (OR=1.4, p=0.004) were associated with moderate and low risks of breast cancer among Asians. Functional characterization of the BRCA2 variants using four quantitative assays showed reduced BRCA2 activity for p.Tyr3035Ser compared to wildtype. Overall, our results show how BRCA2 missense variants that influence protein function can confer clinically relevant, moderately increased risks of breast cancer, with potential implications for risk management guidelines in women with these specific variants.

Keywords: BRCA1, BRCA2, Cancer Risk, Cancer Predisposition, Variants of uncertain significance, functional assay

INTRODUCTION

Mutation screening of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes has resulted in the discovery of thousands of unique germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants. Many pathogenic variants of BRCA1 or BRCA2 resulting in truncation of these proteins, along with a small number of pathogenic missense variants, have been associated with high risks of breast cancer with cumulative risks of 55% to 85% by age 70 (1). In contrast, the influence on cancer risk of many rare variants of uncertain significance (VUS), accounting for between 2% and 10% of results from genetic testing, is not known (2–4). As a result, carriers of VUS in these predisposition genes cannot benefit from cancer risk management strategies for women with pathogenic mutations.

Clinical classification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS has been largely based on probability-based models which incorporate likelihood-ratios associated with family history of cancer, co-segregation of variants with breast and ovarian cancer within families, tumor histopathology, and prior probabilities of pathogenicity associated with cross-species amino acid sequence conservation (5, 6). While over 200 BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants have been classified as pathogenic or neutral/non-pathogenic using a multifactorial likelihood model (7–10), many VUS remain because of limited availability of families segregating the variants. Clinical classification of VUS in BRCA1 and BRCA2 has been further complicated by the identification of variants with partial effects on protein function (5, 11, 12). However, to date only the BRCA1 c.5096G>A, p.Arg1699Gln (R1699Q) variant has been associated with a reduced cumulative risk of breast cancer (24% by age 70) (13). R1699Q has also been associated with lower penetrance relative to the pathogenic c.5095C>T, p.Arg1699Trp (R1699W) variant in the same residue. In this study, the influence of 52 missense variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 on breast cancer risk was investigated using the iCOGS breast cancer case-control project (14). In addition, the impact of the BRCA2 c.9104A>C, p.Tyr3035Ser (Y3035S), c.7522G>A, p.Gly2508Ser (G2508S), and c.8187G>T, p.Lys2729Asn (K2729N) variants on BRCA2 function were evaluated relative to known pathogenic and neutral variants using biochemical, cell-based homology directed repair (HDR), and in vivo embryonic stem (ES) cell-based assays. The combination of these genetic and functional studies show that missense variants in the DNA binding domain of BRCA2 with partial effects on protein function can confer moderate risks of breast cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Breast cancer cases and controls from 38 studies of predominantly European ancestry (41,890 cases with invasive disease and 41,607 controls) and nine studies of Asian ancestry (6,269 cases and 6,624 controls) from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC) were used for genotyping (Supplementary Table S1). All studies were approved by local ethics committees and institutional review boards.

Variant selection

Missense substitution variants from BRCA1 (n=19) and BRCA2 (n=33) were selected by ENIGMA for inclusion on the iCOGS genotyping array based on frequency in the ENIGMA database (15) (Supplementary Tables S2). Variants are defined by Human Genome Variant Society (HGVS) nomenclature and are based of Refseq transcripts (BRCA1: NM_007294.3 ; BRCA2: NM_000059.3).

Genotyping

Genotyping was conducted using the custom Illumina Infinium array (iCOGS) (14). DNA samples containing each of the variants were included in iCOGS genotyping as positive controls and were used to inform genotype calling. Genotypes were called with the GenCall algorithm. Descriptions of sample and genotype quality control have been published (14, 16). Cluster plots for rare variants for this study were manually evaluated relative to positive control samples.

Statistical Methods

Case-control analysis - The association of each variant with breast cancer risk was assessed using unconditional logistic regression, adjusting for study (categorical). Analyses were restricted to either Caucasian or Asian women. Cases selected for iCOGS based on personal or family history of breast cancer were excluded to obtain unbiased OR estimates for the general population. The significance of associations (P-values) was determined by the likelihood ratio test comparing models with and without carrier status as a covariate. Because this study was focused on estimating breast cancer risk associated with each variant, analyses were not adjusted for multiple testing. Moderate risk of breast cancer was defined as odds ratio (OR) from 2.0 to 5.0 and high risk of breast cancer was defined as OR>5.0.

Segregation analysis - Risks of breast cancer were assessed using pedigrees based on the likelihood of the observed pedigree genotypes conditional on the pedigree phenotypes and the genotype of the index case. The primary analysis calculated the penetrance for breast cancer in carriers of the p.Y3035S variant assuming a constant relative risk with age. A second analysis allowed for a similar pattern of age specific effects as for population based pathogenic BRCA2 variants and calculated the optimal cumulative penetrance at 75% of pathogenic BRCA2 variants. The age-specific hazard ratio (HR), by decade, was assumed to be a constant multiple of the population based estimates for BRCA2 pathogenic mutations, with cumulative penetrance re-estimated at each trial value of the multiplier. This provided for a similar pattern of age-specific effects as in BRCA2, but allowed testing of different penetrance values and only required estimation of a single parameter. Models were fitted under maximum likelihood theory using a modified version of the LINKAGE genetic analysis package (17). Non-carriers were assumed to be at population risks with incidence rates taken from cancer registry data obtained from Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, VIII (IARC, Lyon) and risk ratios (RR, the age specific breast cancer incidence rate in carriers divided by the relevant population rate) were estimated. Reported breast cancers with unknown age at diagnosis were excluded from all analyses. Cancers other than breast (including ovarian cancer) were treated as unaffected at the age of their cancer diagnosis.

Cell Lines

V-C8 cells were a kind gift from Dr. M.Z. Zdzienicka. 293T cells were obtained from ATCC (CRL-3216). Cells were authenticated by short tandem repeat analysis using the kit GenePrint10 kit (Promega). All the cell lines used in this study were routinely checked for mycoplasma contamination using the MycoProbe Mycoplasma Detection Set (R&D Systems). Cells were limited to 6 weeks in culture.

Homology directed repair (HDR) assay

The HDR assay for evaluating the influence of variants in the BRCA2 DNA binding domain (DBD) on BRCA2 homologous recombination DNA repair activity has been described previously (11). Full-length human BRCA2 wild-type and mutant cDNA expression constructs were co-expressed with an I-Sce1 expressing plasmid in Brca2 deficient V-C8 cells, stably expressing the DR-GFP reporter plasmid. Homologous recombination-dependent repair of I-Sce1 induced DNA double strand breaks were quantified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) of GFP positive cells after 72 hours. Two independent clones of each variant were evaluated in the HDR assay on three separate occasions. Equivalent expression of wild-type and mutant BRCA2 proteins was confirmed by western blot analysis of anti-Flag-M2 (Sigma F1804) antibody immunoprecipitates from V-C8 cell lysates.

Purification of full-length wild-type and mutated BRCA2 protein

Wild-type and mutant human BRCA2 cDNAs were cloned into the C-terminal MBP-GFP-tagged phCMV1 expression plasmids and purified as described (18, 19). Briefly, 10 × 15-cm plates of HEK293 cells were transiently transfected using TurboFect (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer specifications and harvested 30 hours post-transfection. Cell extracts were bound to Amylose resin (NEB), and the protein was eluted with 10 mM maltose. The eluate was further purified by ion exchange using BioRex 70 resin (BIO-RAD) and step eluted at 250mM, 450 mM, and 1M NaCl (18, 19). Each fraction was tested for nuclease contamination. The 1M NaCl fractions were used for the DNA binding assay because they were free of nuclease contamination.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

The ssDNA substrate (oAC423) used for DNA binding was obtained from Sigma and purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Purified wildtype or mutated BRCA2 at concentrations 0, 1, 5, 10, 20 nM was mixed with the ssDNA oligonucleotide oAC423 167-mer (0.2 μM nt), labeled with 32P at the 5′ end, in a buffer containing 25 mM TrisAcO (pH 7.5), 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 1mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, 100 μg/ml BSA, and incubated for 60 min at 37°C. Reaction products were resolved by 6% PAGE, imaged on a Typhoon PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences), and analyzed with Image Quant software. The relative amount of product was calculated as labeled complex divided by the total labeled input DNA in each lane. The protein-free lane defined the value of 0% complex.

oAC423: 5′-CTGCTTTATCAAGATAATTTTTCGACTCATCAGAAATATCCGTTTCCTATATTTATTCCTATTATGTTTTATTCATTTACTTATTCTTTATGTTCATTTTTTATATCCTTTACTTTATTTTCTCTGTTTATTCATTTACTTATTTTGTATTATCCTTATCTTATTTA-3′.

Embryonic Stem (ES) cell complementation

Selected BRCA2 variants were functionally analyzed based on the ability of human BRCA2 to complement the lethality of mouse Brca2 deficiency (20, 21). BRCA2 exons containing VUS were generated by mutagenesis PCR and engineered into a human BRCA2 (hBRCA2) Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) by Red/ET BAC recombineering in DH10B E.coli. BAC DNA was transfected into mES cells containing a conditional mouse Brca2 allele and a disrupted Brca2 allele (Brca2−/loxP), and the DR-GFP construct integrated at the pim1 locus. hBRCA2 containing cells were selected by G418. Per variant, two independent BAC transfections were performed and G418-resistant clones from each BAC transfection were pooled. Cell pools were transfected with Cre-recombinase expression construct to remove the conditional mBrca2 gene. hBRCA2 RNA and protein expression were confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR and western blotting, respectively.

ES cell functional assays

After Cre-recombinase transfection, mBrca2 depleted cells were selected for restoration of the HPRT minigene using hypoxanthine-aminopterin-thymidine (HAT) containing medium. HAT resistant clones were pooled and evaluated for BRCA2 activity using functional assays. In the mES cell HDR assay, cells were transfected with an I-Sce1 expression vector, pCMV-RED-ISce, and GFP positive cells were quantified by flow cytometry 48 hr after transfection. mES cells were also treated with varying doses of PARP inhibitor (KU-0058948, Astra Zeneca) and viable cells were quantified after 48 hr. Cell survival was calculated as the fraction of treated surviving mES cells relative to the cell count of untreated surviving cells per cell line.

RESULTS

Association of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants with breast cancer risk

A total of 19 BRCA1 and 33 BRCA2 variants encoding missense substitutions and the known pathogenic BRCA1 protein truncating variant c.4327C>T, p.Arg1443Ter (R1443X) were genotyped for 48,159 breast cases and 48,231 controls from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC) on the iCOGS custom genotyping array (Supplementary Table S1). Among the BRCA1 variants, 12 have been classified as Class 1-neutral, 6 as Class 3-uncertain, and 2 as Class 5-pathogenic, by the quantitative multifactorial likelihood model that the ENIGMA consortium (www.enigmaconsortium.org) uses for expert panel review of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants for ClinVar (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar) and BRCA Exchange (http://brcaexchange.org) (Supplementary Table S2). Among the Class 3 variants, BRCA1 c.5207T>C, p.Val1736Ala (V1736A) is known to disrupt BRCA1 activity (22), and both V1736A and c.5363G>A, p.Gly1788Asp (G1788D) are annotated as pathogenic by multiple sources in the ClinVar database. Among the BRCA2 variants, 25 have been classified as Class 1-neutral or Class 2-likely neutral, 6 are Class 3-uncertain, and two (c.8167G>C, p.Asp2723His (D2723H); c.9154C>T, p.Arg3052Trp (R3052W)) have been classified as Class 5-pathogenic using the same multifactorial likelihood model (Supplementary Table S2). Among these, 18 are located in the DNA binding domain (amino acids 2460-3170).

The BRCA1 R1443X truncating pathogenic variant was associated with high risk of breast cancer (odds ratio (OR) = 8.3, p=0.045) in the Caucasian case-control analysis in iCOGS (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3), consistent with what has been estimated for truncating pathogenic BRCA1 variants. Among the missense variants, c.5096G>A, p.Arg1699Gln (R1699Q) was associated with a moderate risk of breast cancer (OR=4.29, p=0.009) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3). This result was lower than expected for pathogenic BRCA1 variants, but consistent with the moderate penetrance of this variant estimated from family-based studies (13). Several BRCA1 variants including the known pathogenic c.5123C>A, p.Ala1708Glu (A1708E); the c.5207T>C, p.Val1736Ala (V1736A); and c.5363G>A, p.Gly1788Asp (G1788D) variants that are identified as pathogenic in ClinVar were not observed in sufficient numbers of cases and controls to allow for estimation of breast cancer risks (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). Three BRCA2 variants were statistically significantly associated with increased breast cancer risk (p<0.05) for Caucasian or Asian women. BRCA2 c.7522G>A, p.Gly2508Ser (G2508S) was observed in 31 cases and 12 controls in the Asian studies (OR=2.68, p=0.004) but not in any Caucasians, BRCA2 c.8187G>T, p.Lys2729Asn (K2729N) was observed in 164 cases and 128 controls in the Asian studies (OR=1.41, p=0.004), and BRCA2 c.9104A>C, p.Tyr3035Ser (Y3035S) was observed in 18 cases and 7 controls in the Caucasian studies (OR=2.52, p=0.038) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3). In addition, the BRCA2 c.4258G>T, p.Asp1420Tyr (D1420Y) (OR=0.86, p=0.005) and c.8149G>T, p.Ala2717Ser (A2717S) (OR=0.77, p=0.02) were negatively associated with risk for Caucasian women (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3). None of the remaining BRCA2 variants, including the Class 5-pathogenic BRCA2 variants, c.8167G>C, p.Asp2723His (D2723H) and c.9154C>T, p.Arg3052Trp (R3052W), were observed in enough cases and controls for estimation of breast cancer risk (Supplementary Table S3). Thus, for the first time BRCA2 variants encoding missense alterations (G2508S, K2729N, and Y3035S) have been associated with moderately (OR<5.0) increased risks of breast cancer.

Table 1.

Variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 significantly associated with breast cancer risk in a case-control analysis

| Sequence Variantsa | Caucasian | Asian | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Gene | HGVS DNA | HGVS Protein | Protein change | Case n=41,890 | Control n=41,607 | ORb | 95% CI | P-value | Case n=6,629 | Control n=6,624 | ORc | 95% CI | P-value |

| c.2521C>T | p.Arg841Trp | R841W | 160 | 207 | 0.81 | 0.66–1.00 | 0.045 | 1 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| BRCA1 | c.4327C>T | p.Arg1443Ter | R1443X | 9 | 1 | 8.3 | 1.05–16.0 | 0.045 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.09–25.75 | 0.76 |

| c.5096G>A | p.Arg1699Gln | R1699Q | 16 | 4 | 4.3 | 1.43–12.85 | 0.009 | 0 | 0 | ND | – | ||

|

| |||||||||||||

| c.4258G>T | p.Asp1420Tyr | D1420Y | 657 | 749 | 0.86 | 0.77–0.96 | 0.005 | 6 | 8 | 1.01 | – | 0.99 | |

| c.7522G>A | p.Gly2508Ser | G2508S | 0 | 0 | ND | – | – | 31 | 12 | 2.7 | 1.37–5.23 | 0.004 | |

| c.8149G>T | p.Ala2717Ser | A2717S | 137 | 185 | 0.8 | 0.62–0.96 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | ND | – | – | |

| BRCA2 | c.8187G>T | p.Lys2729Asn | K2729N | 3 | 1 | 2.8 | 0.29–27.64 | 0.368 | 164 | 128 | 1.4 | 1.12–1.78 | 0.004 |

| c.9104A>C | p.Tyr3035Ser | Y3035S | 18 | 7 | 2.5 | 1.05–6.05 | 0.038 | 3 | 0 | ND | – | – | |

| c.9292T>C | p.Tyr3098His | Y3098H | 14 | 20 | 0.7 | 0.35–1.38 | 0.304 | 0 | 0 | ND | – | – | |

Nucleotide numbering in the reference sequences of BRCA1: NM_007294.3 ; BRCA2: NM_000059.3

: Adjusted for 6 European ancestry principal components

: Adjusted for 2 Asian ancestry principal components

OR: odds ratio

CI: Confidence interval

ND: Not determined

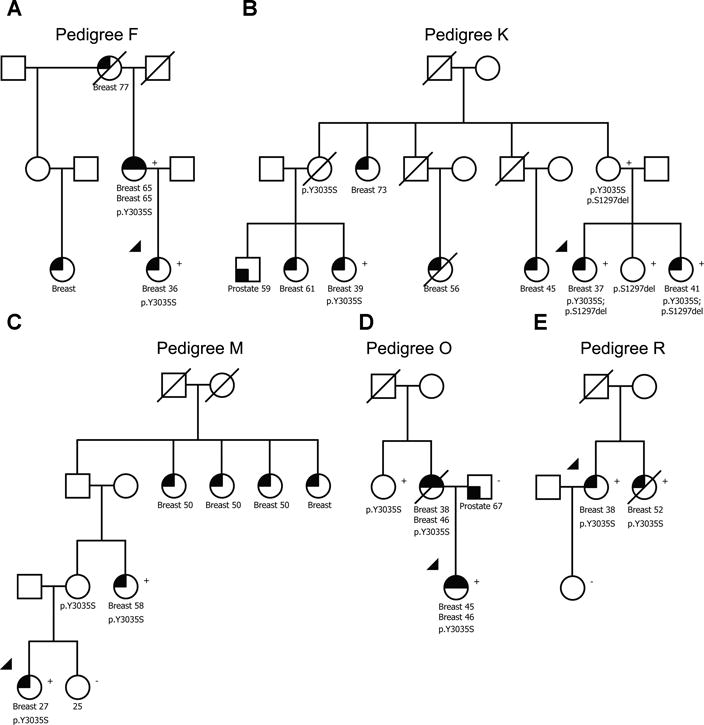

To assess further the association with breast cancer for the BRCA2 G2508S and Y3035S potentially clinically relevant moderate risk variants, pedigrees for segregation analysis were collected through the ENIGMA consortium. Nineteen pedigrees with the Y3035S variant were collected (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S1, Supplementary Table S4). Only one pedigree was obtained for G2508S suggesting this variant is rare in the Caucasian population. Segregation studies of Y3035S, assuming the relative risk was constant with age, indicated an association with breast cancer risk (Risk Ratio (RR)=14.8; 95%CI 2.4–20.0) (Supplementary Table S4). A second analysis, allowing for a similar pattern of age specific effects as for population-based pathogenic BRCA2 truncating variants, estimated the optimal cumulative penetrance for Y3035S at 0.75 of known pathogenic truncating BRCA2 variants, and yielded a similar risk ratio for breast cancer (Supplementary Table S4). Y3035S co-occurred with a pathogenic BRCA2 variant (S1882X) in Pedigree G (Supplementary Fig. S1). Co-occurrence with S1298del in Pedigree K (Figure 1) was not informative because S1298del is a VUS. Together the case-control study and the pedigree analysis suggest that Y3035S is associated with moderately increased breast cancer risk.

Figure 1.

BRCA2 p.Y3035S segregates with breast cancer in high risk families. Five of the most informative pedigrees are shown. Upper black quadrants reflect breast cancer status. Type of cancer and age at diagnosis are displayed. Variant status is indicated by “Y3035S”. (+), mutation positive; (−), mutation negative reflects results of genetic testing.

Cell-based HDR analysis of BRCA2 variants

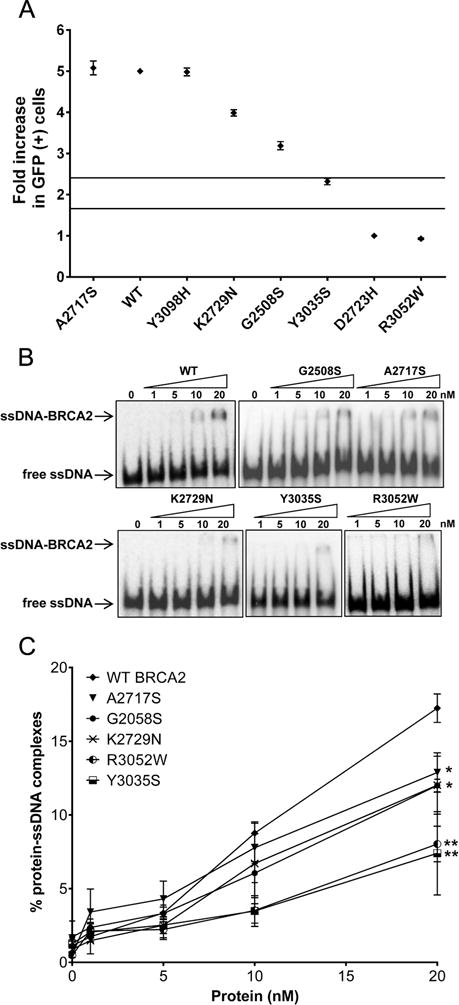

Inactivation or depletion of BRCA2 has been associated with deficient homology directed repair (HDR) of DNA double strand breaks (23), which can be quantified with a cell-based HDR green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter assay (24). This assay has shown 100% sensitivity and specificity for known pathogenic missense variants in the BRCA2 DNA-binding domain and has been used for characterization of BRCA2 VUS (8, 11, 25). In this study, the impact of the G2508S, A2717S, K2729N, and Y3035S missense variants on BRCA2 HDR activity was assessed relative to the D2723H and R3052W known pathogenic and the c.9292T>C p.Tyr3098His (Y3098H) known neutral BRCA2 variants (11, 26). D1420Y was not evaluated because the variant is not located in the BRCA2 DBD. All wildtype and mutant BRCA2 proteins displayed equivalent levels of expression relative to β-actin by western blot (Supplementary Fig. S2). The D2723H and R3052W Class 5 pathogenic variants (11) showed substantial loss of BRCA2 HDR activity (Fig. 2A and Table 2). In contrast, BRCA2 Y3035S showed intermediate levels (2.3-fold relative to D2723H) (Fig. 2A and Table 2) of BRCA2 HDR activity. This was outside the thresholds for known pathogenic and neutral missense variants (HDR fold-change <1.66 and >2.41, respectively, that equate to 99% probabilities of pathogenicity and neutrality(11). This intermediate functional effect was consistent with the moderate risk of breast cancer (OR=2.52, p=0.038) observed in the iCOGS case-control study (Table 1) and the estimated 0.75-fold penetrance of pathogenic BRCA2 variants from segregation studies (Supplementary Table S4). This is the first evidence that reduced BRCA2 function is associated with an intermediate or moderate risk of breast cancer.

Figure 2.

(A) HDR and ssDNA binding activity of BRCA2 p.Y3035S is reduced. (A) Activity of BRCA2 missense variants is shown as HDR fold change with standard error (SE) (of three independent measures of duplicates) on a scale of one to five. Solid lines represent 99.9% and 0.1% probability of pathogenicity. (B) Representative Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSA) of DNA-protein complexes formed by mixing increasing concentrations (0, 5, 10, 20 nM) of purified BRCA2 wildtype and mutant proteins with ssDNA. (C) Quantitation of the DNA-protein complex formation shown in Fig. 2B. Error bars represent SE derived from at least three independent experiments. Statistical difference between WT and mutant BRCA2 protein-DNA complexes formation was determined by two-sample t-test. **p<0.001; *p<0.05. WT, wildtype.

Table 2.

Summary of functional effects of each BRCA2 variant measured by four independent assay

| Variants | Odds ratio | V-C8 HDR assay | Protein-DNA binding | ES cells HDR assay | PARP inhibitor response | Overall impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold-change +/− SE | % protein complexes at 20nM | Relative HR +/− SE | % survival at 125nM +/− SE | |||

| Wildtype | N/A | 5.00 | 17.47+/−0.01 | 1.00 | 105+/−11 | (+) Wildtype |

| Y31C | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.14+/−0.06 | 46+/−11 | (—) Deleterious |

| G2508S | 2.7 | 3.19+/−0.10 | 12.00+/−0.43 | 0.56+/−0.10 | 99+/−3 | (−) Mild effect |

| A2717S | 0.8 | 5.08+/−0.17 | 12.88+/−1.89 | 0.85+/−0.20 | 90+/−14 | (+) Neutral |

| D2723H | N/A | 1.00 | N/A | N/A | N/A | (—) Deleterious |

| K2729N | 1.4 | 3.99+/−0.08 | 12.12+/−1.96 | 0.70+/−0.11 | 81+/−15 | (−) Mild effect |

| Y3035S | 2.5 | 2.32+/−0.08 | 7.39+/−2.83 | 0.50+/−0.15 | 80+/−11 | (–) Moderate effect |

| R3052W | N/A | 0.93+/−0.02 | 8.03+/−2.09 | N/A | N/A | (—) Deleterious |

| Y3098H | 0.7 | 4.98+/0.09 | N/A | N/A | N/A | (+) Neutral |

SE: standard error of the mean; N/A: not applicable

In contrast, BRCA2 G2508S exhibited 3.2-fold HDR activity relative to D2723H (Fig. 2A and Table 2). While reduced relative to wildtype activity, this level of HDR activity was associated with >99% probability of neutrality. Similarly, BRCA2 K2729N showed reduced HDR activity relative to the wildtype protein (Fig. 2A and Table 2), which was consistent with a mild influence on breast cancer risk (OR=1.41, p=0.004) in the Asian population, and >99% probability of neutrality (Fig. 2A). Together these results show that the HDR assay is calibrated relative to levels of cancer risk, with minor functional effects for variants associated with low- or modest risks of breast cancer such as c.9976A>T, p.Lys3326Ter (K3326X) (OR=1.28) (27) and K2729N (OR=1.41), more substantial functional effects for the intermediate risk Y3035S (OR=2.52), and strong effects for known pathogenic variants such as D2723H and R3052W (Fig. 2A). Thus, the HDR assay may predict the level of risk associated with any BRCA2 DBD variant.

Single strand DNA (ssDNA) binding activity of BRCA2 variants

BRCA2 directly binds to ssDNA and recruits RAD51 to ssDNA at sites of DNA damage during homologous recombination DNA repair (18, 28). Hence, ssDNA binding is integral to the homologous recombination activity of BRCA2. On this basis, an in vitro biochemical assay was used to examine the influence of the BRCA2 variants on BRCA2 ssDNA binding activity. Full-length wildtype and mutant human BRCA2 proteins tagged with (N-terminal) green fluorescence protein (GFP) and maltose-binding protein (MBP) (GFP-MBP-BRCA2) were expressed and purified to near homogeneity (Supplementary Fig. S3) as described previously (18, 19). Full-length BRCA2 protein expression was confirmed by western blotting using an antibody against the C-terminus of BRCA2 (Supplementary Fig. S3). The ssDNA binding activity of full-length wildtype and mutant BRCA2 proteins was evaluated using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). The wildtype protein bound to ssDNA with a yield of ~18% at the maximum attainable concentration of BRCA2 protein (Fig. 2B, 2C, and Table 2), consistent with previous results (18), whereas the R3052W pathogenic control exhibited 2-fold reduced protein-ssDNA complex formation (~8%) (Fig. 2B, 2C, and Table 2). Likewise, the Y3035S variant exhibited 2-fold reduced complex formation compared to the wildtype protein (Fig. 2B, 2C, and Table 2). In contrast, G2508S, A2717S, and K2729N showed only partially reduced (~12% to 13%) protein-ssDNA complex formation (Fig. 2B, 2C, and Table 2). These findings are consistent with predictions from the crystal structure of the BRCA2 DBD, where Y3035S is predicted to impair DNA binding, similarly to R3052W, because of proximity to DNA in the ssDNA-BRCA2 complex (Supplementary Fig. S4) (26). Overall, the results suggest that the reduction in HDR activity observed for Y3035S (Fig. 2A) is due to a defective ssDNA binding activity.

Mouse embryonic stem cell-based functional analysis of BRCA2 missense variants

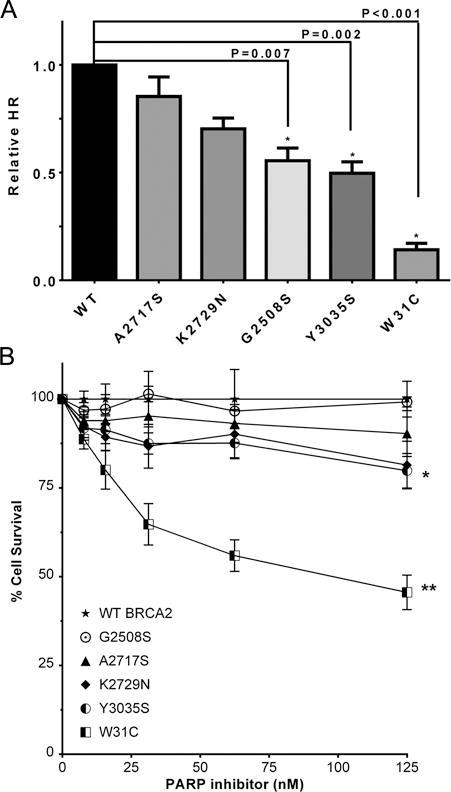

Functional complementation of murine (m) Brca2-null ES cell lethality by human (h) BRCA2 variants (20, 21) has been used to characterize BRCA2 VUS. Wildtype human BRCA2 expression rescues Brca2 deficient ES cells from lethality, whereas ES cells expressing known pathogenic forms of BRCA2 fail to survive (20). In addition, several variants have shown partial or reduced ES cell survival relative to wildtype BRCA2. Surviving cells expressing these variants have shown moderate defects in HDR assays and sensitivity to cisplatin or a PARP inhibitor (29). In this study two independent pools of BAC clones for each of hBRCA2 G2508S, A2717S, D2723H, K2729N, Y3035S, and R3052W were tested for complementation of mBrca2 deficiency and HDR activity. Cells expressing hBRCA2 D2723H or R3052W pathogenic variants did not survive after disrupting endogenous mBrca2 expression and were not included in the downstream functional analysis. Instead, we included mES cells expressing the W31C variant as a negative control. This variant conferred a severe defect in HDR activity because of disruption of the BRCA2-PALB2 interaction (30).

BRCA2 W31C, G2508S, A2717S, K2729N, and Y3035S BACs rescued the lethality of the mBrca2-deficient ES cells, suggesting at least partial functional complementation of mBrca2 deficiency. HDR activity of surviving cells was assessed using the DR-GFP reporter assay. BRCA2 W31C showed only 14% (p<0.001) activity, whereas BRCA2 Y3035S, G2508S, and K2729N variants displayed 50% (p=0.002), 55% (p=0.007), and 70% (p=0.02) of wildtype HDR activity, respectively (Fig. 3A and Table 2). In contrast, HDR activity in cells expressing A2717S was not significantly different to wildtype protein (Fig. 3A and Table 2). The sensitivity of wildtype and mutant BRCA2 expressing ES cells to PARP inhibitor (KU-0058948) was evaluated to determine whether the reduction in HDR associated with some of the variants was sufficient to confer sensitivity to PARP inhibitor. Sensitivity was evaluated by counting viable cells after 48 hours of exposure to different doses of drug. Wildtype BRCA2, G2508S, and A2717S did not show sensitivity to PARP inhibitor, whereas W31C expressing cells showed significant sensitivity (Fig. 3B and Table 2). K2729N and Y3035S resulted in partial rescue of ES cell sensitivity (Fig. 3B and Table 2). Collectively, the ES cell HDR activity of the variants showed high concordance with the ORs from the case-control study, with Y3035S displaying partially deficient BRCA2 activity. In contrast, the level of HDR activity did not correlate well with different levels of PARP inhibitor sensitivity, although Y3035S was partially sensitive to PARP inhibitor, consistent with the results from other assays.

Figure 3.

HR efficiency and PARP inhibitor sensitivity of mES cells expressing hBRCA2 variants. (A) GFP expression from the DR-GFP reporter was analyzed as a measure of HR activity. The percentage GFP positive cells for each variant was normalized to wildtype hBRCA2 expressing cells. Results represent the mean of three independent experiments with two independent pools of BAC clones tested per variant. Error bars represent SE of three independent experiments. Statistical significance is indicated by “ * ”. (B) Relative cell survival compared to untreated cells was determined by cell count after 48hr exposure to PARP inhibitor KU-0058948. Data represent the mean of three experiments using two independent pools of BAC clones. **p<0.001; *p<0.05. WT, wildtype.

DISCUSSION

In this study, associations between 52 BRCA1 and BRCA2 missense variants and breast cancer risk were evaluated using a large breast cancer case-control study. To our knowledge, this is the largest case-control study conducted to establish the clinical relevance and estimate the risks of individual rare BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants encoding missense substitutions. The case-control analysis showed that BRCA1 c.5096G>A, R1699Q (OR=4.29) and BRCA2 c.9104A>C, Y3035S (OR=2.52) were associated with moderately increased breast cancer risks for Caucasian women (Table 1), whereas BRCA2 c.7522G>A, G2508S (OR=2.68) and c.8187G>T, K2729N (OR=1.41) were associated with increased risks for Asian women. This is the first study to estimate low to moderate risks of breast cancer for specific BRCA1 and BRCA2 missense variants.

The moderate risk of breast cancer associated with the BRCA1 R1699Q variant (OR=4.29) was consistent with previous findings from segregation analyses of breast cancer families, which estimated that R1699Q was associated with a cumulative risk of breast or ovarian cancer by age 70 years of 24% relative to the pathogenic R1699W variant and BRCA1 truncating variants (13). Similarly the quantitative ENIGMA multifactorial likelihood prediction model based on family data and sequence conservation yielded a posterior probability of pathogenicity for R1699Q of only 0.79 (13). Consistent with these findings, BRCA1 R1699Q protein has shown only partial protein function in HDR and other in vitro experiments (12, 13). Thus, the case-control study and functional studies are consistent in identifying R1699Q as a moderate risk variant in BRCA1.

BRCA2 Y3035S was associated with increased risk of disease (OR=2.52) for Caucasian women. While the numbers of cases and controls with the Y3035S variant were small, the moderate risk estimate is supported by family data showing partial co-segregation with breast cancer, and one pedigree in which BRCA2 Y3035S co-occurred with BRCA2 c.5645C>A p.Ser1882Ter (S1882X) (Supplementary Fig. S1). Several sequence-based in silico prediction models including MetaLR, MetaSVM, Vest3, and A-GVGD (prior probability of pathogenicity of 0.66) (Supplemental Table S2) predicted Y3035S as deleterious. In addition, the missense substitution is predicted as likely deleterious by a protein likelihood ratio model based on sequence analysis (31). Analyses of splicing defects using Minigene-based assays have shown no influence on RNA splicing (32), suggesting that the increased risks are not due to abnormal splicing. Importantly, functional analysis of Y3035S using multiple independent assays consistently revealed partial activity. Y3035S showed intermediate BRCA2 HDR activity in VC8 cells, failed to restore HDR activity in ES cells (Fig. 3A), and only partially rescued sensitivity to PARP inhibition in ES cells (Fig. 3B). Similarly, Y3035S showed significantly reduced ssDNA complex formation (Fig. 2B and 2C) consistent with the location of Y3035 in the crystal structure of the BRCA2 DBD (28) (Supplementary Fig. S4). Together the functional studies indicate that Y3035S is a hypomorphic BRCA2 variant. Overall the case-control association study and functional analyses provide the first evidence that a hypomorphic BRCA2 missense variant can confer a moderate risk of breast cancer. However, Y3035S is consistently reported as “likely benign” and “benign” in the ClinVar public database. Since this database is widely used by researchers and clinicians, this under-appreciation of moderate risks of breast cancer associated with this variant has the potential to impact patient care. Further prospective studies are required to estimate age-dependent risks of cancer and to inform management protocols for carriers of this and other hypomorphic BRCA2 variants.

The BRCA2 G2508S (OR=2.68, p=0.004) variant was associated with a moderate risk of breast cancer in Asian women, but could not be evaluated in the Caucasian population (Table 1). The variant was predicted neutral by a protein likelihood prediction model (31), but was predicted deleterious by other in silico prediction models including MetaLR, MetaSVM, Vest3, and A-GVGD (prior probability of pathogenicity of 0.66) (Supplementary Table S2). However, the HDR V-C8 cell-based assay showed only mildly reduced activity similar to K2729N (OR=1.41) and p.K3326X (OR=1.28) (27), which are both classified as neutral (Fig. 2A). Likewise, the impact of G2508S on ssDNA binding was limited and most similar to K2729N (Fig. 2B, 2C). Although G2508S only partially rescued HDR activity in ES cells (Fig. 3A), the variant completely rescued sensitivity to PARP inhibition in ES cells similar to wildtype BRCA2 (Fig. 3B). Thus, the functional results suggest a limited impact on BRCA2 activity. As the variant has only been detected in the East Asian population (33, 34), one possibility is that genetic and environmental modifiers in the Asian population account in part for the influence of the variant on breast cancer risk and the discrepancy between the case-control and functional study results. Further studies are needed to resolve this issue, but for now the breast cancer risks associated with this variant must be treated with caution. BRCA2 K2729N (OR=1.41, p=0.004) is also common in Asians, but rare in Caucasians (34). This variant has previously been classified as neutral by the multifactorial likelihood classification model (8). Consistent with these findings, functional analysis of K2729N showed only a minor influence on HDR function (8, 11) (Fig. 2A) and ssDNA binding (Fig. 2B), and substantial rescue of ES cell-based HR (Fig. 3A) and ES cell drug sensitivity (Fig. 3B). The mild defect in HR function correlated well with the low risk of breast cancer (OR=1.41, P=0.004) associated with the K2729N variant in the Asian case-control study.

This study contains the first evidence that a biochemical assay using purified full-length BRCA2 protein can be used to assess the DNA binding capacity of missense variants in the BRCA2 DBD. While purification of wildtype full-length BRCA2 protein to near homogeneity has previously been described (18, 19), in this study the functional integrity of purified mutant BRCA2 proteins was assessed for the first time in a quantitative ssDNA binding assay. Full-length proteins were used to limit potentially inaccurate interpretation of effects from partial protein fragments. The correlation of the ssDNA binding assay and HDR activity and the structural inspection of the DNA binding domain suggest that the reduction in HDR activity may result from a defect in ssDNA binding. The study also showed that the influence of BRCA2 variants on HDR activity does not fully predict the response to PARP inhibitor in ES cells (Fig. 3A and 3B). These findings suggest that only large reductions in HDR activity (<50%) will result in PARP inhibitor sensitivity. Whether tumors associated with these missense variants are sensitive to PARP inhibitor remains to be determined.

Many unique missense variants and VUS in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been reported in the Clinvar database but no validated high throughput methods for clinical classification of missense variants in these genes have been established. Current methods of classification rely heavily on family data. This study highlights the potential for incorporating results from functional assays in the variant classification process, especially when family data is scarce. In particular, evaluation of missense variants in the BRCA2 DBD is possible with the cell-based HDR assay (11). Importantly, HDR results for variants with low or moderate levels of risk [K3326X (OR=1.28) (27), K2729N (OR=1.41), Y3035S (OR=2.52)], suggest that the HDR assay can be calibrated to differentiate between variants with high, moderate, or low breast cancer risks (Fig. 2A). Additional studies that combine the HDR assay data with family-based and sequence based models may result in classification of certain BRCA2 VUS as moderate breast cancer risk missense variants. ES cell complementation assays have also been used to identify inactivating missense variants in the BRCA2 DBD (14, 20, 29, 35), although the assay needs to be validated relative to known pathogenic and neutral BRCA2 variants before the results can be incorporated into VUS classification models.

In summary, this study establishes for the first time the existence of BRCA2 missense variants that are associated with moderate risks of breast cancer. Only through the very large iCOGS case-control association study was it possible to define the BRCA2 missense variant (Y3035S) as a moderate risk pathogenic variant for breast cancer (OR=2.52, p=0.038). Functional studies showed consistent partial or hypomorphic activity associated with Y3035S, suggesting that other BRCA2 variants with partial protein activity should be evaluated for moderate risks of breast cancer. Given that the age-related and lifetime risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with moderate risk variants are likely to be substantially lower than for known pathogenic missense and truncating BRCA2 variants, risk management guidelines for individuals with these mutations may need to be redefined. Because Y3035S appears to confer similar risks of breast cancer as CHEK2 or ATM inactivating mutations, perhaps individuals carrying Y3035S or other moderate risk BRCA2 variants may benefit from following management guidelines similar to individuals with CHEK2 and ATM variants rather than individuals with high-risk pathogenic BRCA2 variants. However, further studies are needed to establish accurate risks of cancer associated with hypomorphic, moderate risk BRCA2 variants before any modifications are considered. Ongoing efforts are focused on estimating cancer risks associated with additional selected hypomorphic/intermediate function variants through segregation studies in families, with the goal of calibrating the functional results with levels of cancer risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shyam Sharan for the Pl2F7 conditional mBrca2 knockout mES cell line and Maria Jasin for the DR-GFP targeting construct.

Financial Support:

This work was supported in part by NIH grants CA116167, CA176785, CA192393, an NIH specialized program of research excellence (SPORE) in breast cancer to the Mayo Clinic (P50 CA116201), the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (F.C. Couch), the ATIP-AVENIR CNRS/INSERM Young Investigator grant 201201, EC-Marie Curie Career Integration grant CIG293444, Institute National du Cancer INCa-DGOS_8706 to A.C (A. Carreira), the Dutch Cancer Society KWF (UL2012-5649) (M.P.G. Vreeswijk), the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (ID#1010719), and The Cancer Council Queensland (ID#1086286) (A. Spurdle). BCAC data management was funded by Cancer Research UK (C1287/A10118 and C1287/A12014) and by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement 223175 (HEALTH-F2-2009-223175) (D.F. Easton). Funding for the iCOGS infrastructure came from: the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement n° 223175 (COGS; HEALTH-F2-2009-223175) (P. Hall), Cancer Research UK (C1287/A10118, C1287/A 10710, C12292/A11174, C1281/A12014, C5047/A8384, C5047/A15007, C5047/A10692) (D.F. Easton), the National Institutes of Health (CA128978) (F.J. Couch) and Post-Cancer GWAS initiative (1U19 CA148537, C.A. Haiman; 1U19 CA148065, D.F. Easton; and 1U19 CA148112 - the GAME-ON initiative, T.A. Sellers), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) for the CIHR Team in Familial Risks of Breast Cancer (I. Andrulis), and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (F.J. Couch).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, Risch HA, Eyfjord JE, Hopper JL, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case Series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(5):1117–30. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quiles F, Fernandez-Rodriguez J, Mosca R, Feliubadalo L, Tornero E, Brunet J, et al. Functional and structural analysis of C-terminal BRCA1 missense variants. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radice P, De Summa S, Caleca L, Tommasi S. Unclassified variants in BRCA genes: guidelines for interpretation. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(Suppl 1):i18–23. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindor NM, Goldgar DE, Tavtigian SV, Plon SE, Couch FJ. BRCA1/2 sequence variants of uncertain significance: a primer for providers to assist in discussions and in medical management. Oncologist. 2013;18(5):518–24. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldgar DE, Easton DF, Deffenbaugh AM, Monteiro AN, Tavtigian SV, Couch FJ. Integrated evaluation of DNA sequence variants of unknown clinical significance: application to BRCA1 and BRCA2. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(4):535–44. doi: 10.1086/424388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vallee MP, Francy TC, Judkins MK, Babikyan D, Lesueur F, Gammon A, et al. Classification of missense substitutions in the BRCA genes: a database dedicated to Ex-UVs. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(1):22–8. doi: 10.1002/humu.21629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Easton DF, Deffenbaugh AM, Pruss D, Frye C, Wenstrup RJ, Allen-Brady K, et al. A systematic genetic assessment of 1,433 sequence variants of unknown clinical significance in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 breast cancer-predisposition genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(5):873–83. doi: 10.1086/521032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrugia DJ, Agarwal MK, Pankratz VS, Deffenbaugh AM, Pruss D, Frye C, et al. Functional assays for classification of BRCA2 variants of uncertain significance. Cancer Res. 2008;68(9):3523–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee MS, Green R, Marsillac SM, Coquelle N, Williams RS, Yeung T, et al. Comprehensive analysis of missense variations in the BRCT domain of BRCA1 by structural and functional assays. Cancer Res. 2010;70(12):4880–90. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindor NM, Guidugli L, Wang X, Vallee MP, Monteiro AN, Tavtigian S, et al. A review of a multifactorial probability-based model for classification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants of uncertain significance (VUS) Hum Mutat. 2012;33(1):8–21. doi: 10.1002/humu.21627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guidugli L, Pankratz VS, Singh N, Thompson J, Erding CA, Engel C, et al. A classification model for BRCA2 DNA binding domain missense variants based on homology-directed repair activity. Cancer Res. 2013;73(1):265–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lovelock PK, Spurdle AB, Mok MT, Farrugia DJ, Lakhani SR, Healey S, et al. Identification of BRCA1 missense substitutions that confer partial functional activity: potential moderate risk variants? Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(6):R82. doi: 10.1186/bcr1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spurdle AB, Whiley PJ, Thompson B, Feng B, Healey S, Brown MA, et al. BRCA1 R1699Q variant displaying ambiguous functional abrogation confers intermediate breast and ovarian cancer risk. J Med Genet. 2012;49(8):525–32. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michailidou K, Hall P, Gonzalez-Neira A, Ghoussaini M, Dennis J, Milne RL, et al. Large-scale genotyping identifies 41 new loci associated with breast cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):353–61. doi: 10.1038/ng.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spurdle AB, Healey S, Devereau A, Hogervorst FB, Monteiro AN, Nathanson KL, et al. ENIGMA–evidence-based network for the interpretation of germline mutant alleles: an international initiative to evaluate risk and clinical significance associated with sequence variation in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(1):2–7. doi: 10.1002/humu.21628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pharoah PD, Tsai YY, Ramus SJ, Phelan CM, Goode EL, Lawrenson K, et al. GWAS meta-analysis and replication identifies three new susceptibility loci for ovarian cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):362–70. doi: 10.1038/ng.2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lathrop GM, Lalouel JM, Julier C, Ott J. Strategies for multilocus linkage analysis in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(11):3443–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen RB, Carreira A, Kowalczykowski SC. Purified human BRCA2 stimulates RAD51-mediated recombination. Nature. 2010;467(7316):678–83. doi: 10.1038/nature09399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez JS, von Nicolai C, Kim T, Ehlen A, Mazin AV, Kowalczykowski SC, et al. BRCA2 regulates DMC1-mediated recombination through the BRC repeats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(13):3515–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601691113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuznetsov SG, Liu P, Sharan SK. Mouse embryonic stem cell-based functional assay to evaluate mutations in BRCA2. Nat Med. 2008;14(8):875–81. doi: 10.1038/nm.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendriks G, Morolli B, Calleja FM, Plomp A, Mesman RL, Meijers M, et al. An efficient pipeline for the generation and functional analysis of human BRCA2 variants of uncertain significance. Hum Mutat. 2014;35(11):1382–91. doi: 10.1002/humu.22678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domchek SM, Tang J, Stopfer J, Lilli DR, Hamel N, Tischkowitz M, et al. Biallelic deleterious BRCA1 mutations in a woman with early-onset ovarian cancer. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(4):399–405. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moynahan ME, Chiu JW, Koller BH, Jasin M. Brca1 controls homology-directed DNA repair. Mol Cell. 1999;4(4):511–8. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu K, Hinson SR, Ohashi A, Farrugia D, Wendt P, Tavtigian SV, et al. Functional evaluation and cancer risk assessment of BRCA2 unclassified variants. Cancer Res. 2005;65(2):417–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Couch FJ, Rasmussen LJ, Hofstra R, Monteiro AN, Greenblatt MS, de Wind N. Assessment of functional effects of unclassified genetic variants. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(11):1314–26. doi: 10.1002/humu.20899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lovelock PK, Wong EM, Sprung CN, Marsh A, Hobson K, French JD, et al. Prediction of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation status using post-irradiation assays of lymphoblastoid cell lines is compromised by inter-cell-line phenotypic variability. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;104(3):257–66. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9415-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meeks HD, Song H, Michailidou K, Bolla MK, Dennis J, Wang Q, et al. BRCA2 Polymorphic Stop Codon K3326X and the Risk of Breast, Prostate, and Ovarian Cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(2) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H, Jeffrey PD, Miller J, Kinnucan E, Sun Y, Thoma NH, et al. BRCA2 function in DNA binding and recombination from a BRCA2-DSS1-ssDNA structure. Science. 2002;297(5588):1837–48. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5588.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biswas K, Das R, Eggington JM, Qiao H, North SL, Stauffer S, et al. Functional evaluation of BRCA2 variants mapping to the PALB2-binding and C-terminal DNA-binding domains using a mouse ES cell-based assay. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(18):3993–4006. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia B, Sheng Q, Nakanishi K, Ohashi A, Wu J, Christ N, et al. Control of BRCA2 cellular and clinical functions by a nuclear partner, PALB2. Mol Cell. 2006;22(6):719–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karchin R, Agarwal M, Sali A, Couch F, Beattie MS. Classifying Variants of Undetermined Significance in BRCA2 with protein likelihood ratios. Cancer Inform. 2008;6:203–16. doi: 10.4137/cin.s618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thery JC, Krieger S, Gaildrat P, Revillion F, Buisine MP, Killian A, et al. Contribution of bioinformatics predictions and functional splicing assays to the interpretation of unclassified variants of the BRCA genes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(10):1052–8. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bodian DL, McCutcheon JN, Kothiyal P, Huddleston KC, Iyer RK, Vockley JG, et al. Germline variation in cancer-susceptibility genes in a healthy, ancestrally diverse cohort: implications for individual genome sequencing. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536(7616):285–91. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biswas K, Das R, Alter BP, Kuznetsov SG, Stauffer S, North SL, et al. A comprehensive functional characterization of BRCA2 variants associated with Fanconi anemia using mouse ES cell-based assay. Blood. 2011;118(9):2430–42. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-324541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.