Abstract

Hundreds of genetically characterized cell lines are available for the discovery of genotype-specific cancer vulnerabilities. However, screening large numbers of compounds against large numbers of cell lines is currently impractical, and such experiments are often difficult to control1-4. Here, we report a method called PRISM that allows pooled screening of mixtures of cancer cell lines by labeling each cell line with 24-nucleotide barcodes. PRISM displayed the expected patterns of cell killing seen in conventional (unpooled) assays. In a screen of 102 cell lines across 8,400 compounds, PRISM led to the identification of BRD-7880 as a potent and highly specific inhibitor of aurora kinases B and C. Cell line pools also efficiently formed tumors as xenografts, and PRISM recapitulated the expected pattern of erlotinib sensitivity in vivo.

Cell lines have long served as tools for oncology drug discovery5. Their track record in predicting efficacy in patients, however, has been mixed. Cell line models have often been chosen more for their tractability than for their reflection of genetic diversity across human cancers. Unsurprisingly, generalizations from studies of few numbers of cell lines have met with limited success. With the ability to comprehensively characterize the genomes of tumors has come the recognition that the varied responses of patients to treatment are largely explained by the genetic diversity of cancer. Recent reports show that this diversity is reflected in established cell lines3, 4. It has also become possible to profile the activity of compounds across large numbers of cell lines and then correlate response to specific genetic features3, 4, 6, 7. Unfortunately, the profiling of drugs across large numbers of cell lines is often intractable because of the time and resources involved.

We hypothesized that the challenge of profiling hundreds of cell lines might be addressed by a pooled approach. Assaying cell lines in pools has the theoretical advantages of (a) increasing throughput and (b) allowing for internally controlled experiments (whereby each cell within a pool is exposed to identical drug concentrations and culture conditions). While cell-cell interactions or paracrine effects of different cell lines growing in a pool could, in principle, confound patterns of drug sensitivity observed in cell lines cultured alone, we reasoned that such concerns would be outweighed by the throughput advantage of a pooled approach. We also note that in vivo, tumors grow not as uniform masses of cells but rather as complex mixtures of genetically diverse tumor cells8 and non-malignant cells of the tumor microenvironment.

For deconvoluting pools of cancer cell lines, we used molecular barcoding because of the nearly limitless number of barcodes and the availability of a flexible, high-throughput (500-plex) barcode detection system based on Luminex microspheres, which have been used in multiplexed assays of gene expression9, protein phosphorylation10, and in genetic screens of PI3-kinase inhibitor activity11

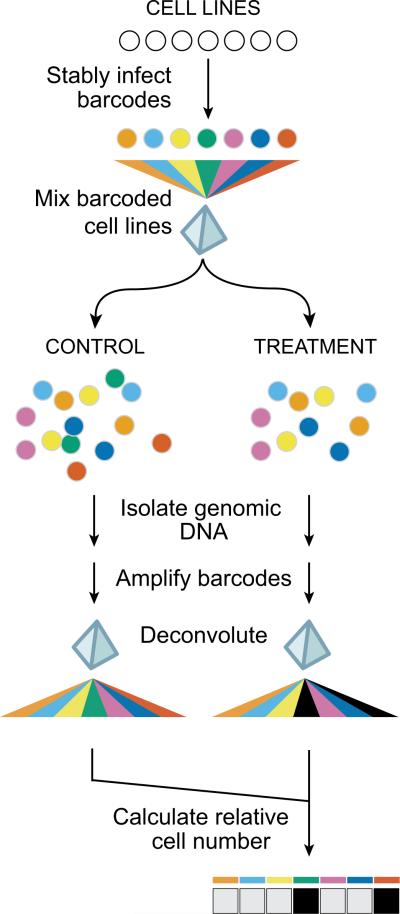

We designed the PRISM assay using lentiviral vectors which permitted stable integration of 24-basepair DNA barcode sequences engineered to have limited sequence homology to the human genome. Common primer sites flanking the barcode sequence allowed for amplification of barcodes with a single set of primers (including one biotinylated primer). Amplicons were then hybridized to Luminex microspheres of distinct colors (each coupled to a different anti-barcode oligonucleotide) and stained with phycoerythrin-streptavidin. Hybridization events were then quantitated on a Luminex detector, wherein the bead color denotes the barcode identity and the phycoerythrin intensity reveals barcode abundance, a direct reflection of cell number (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. PRISM method.

24-basepair DNA barcodes encoded within lentiviruses are stably integrated into individual tumor cell lines after blasticidin selection, and barcoded cell lines are individually frozen and later thawed to generate mixtures of equal numbers of barcoded cell lines, which are frozen again. Thawed mixtures are plated and then rearrayed into tissue culture assay plates. Mixtures are treated with test compounds or vehicle (DMSO) controls. At assay conclusion, genomic DNA is harvested from the mixture of remaining viable cells. Barcode sequences are amplified using polymerase chain reaction and universal primers (one of which is biotinylated), and amplified sequences are hybridized to individual microbeads harboring antisense barcode sequences and then to streptavidin-phycoerythrin. A Luminex FlexMap detector quantitates fluorescent signal for each bead. To adjust for differing barcoding efficiencies and differing cell doubling, the signal for each barcoded cell line is scaled to that of vehicle-treated control, thus demonstrating relative inhibition profiles for specific test compounds across multiple cell lines in mixture.

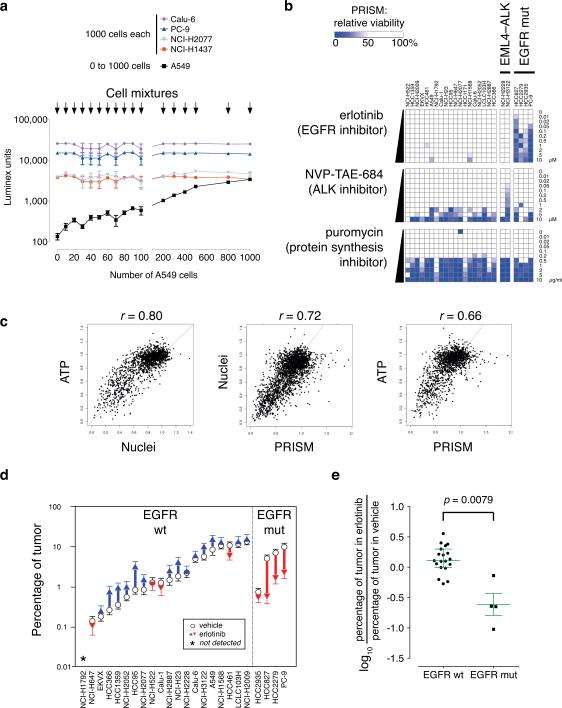

To establish feasibility and determine the sensitivity of PRISM, five barcoded adenocarcinoma cell lines were analyzed. One thousand cells each of four barcoded lines were plated in mixture, and the fifth line added in varying number. The following day, genomic DNA was harvested from the mixtures, and barcodes detected. As predicted, the four invariant lines showed similar signals in all mixtures, while the varied fifth line gave a signal directly proportional to cell number (Fig. 2a). The assay was highly sensitive, able to detect as few as 10 cells in a mixture of 4000 (i.e., < 0.5% of the total cell number).

Figure 2. PRISM in vitro and in vivo.

a. Barcode signal is proportional to cell number. Five human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines (NCI-H1437, PC-9, NCI-H2077, Calu-6, and A549) were labeled with lentivirus encoding one of five specific 24-basepair DNA barcode sequences and driving expression of the bsd blasticidin resistance gene; each cell line was selected for blasticidin resistance. Designated numbers of cells were plated together in mixture in a well of a 96-well tissue culture plate: 1000 cells each of four cell lines (NCI-H1437, PC-9, NCI-H2077, and Calu-6) and 0–1000 cells of one cell line (A549). The following day, genomic DNA was prepared from cell mixtures, and polymerase chain reaction-amplified barcodes were hybridized to microbeads corresponding to each barcode; quantitative fluorescent signals were read on a Luminex FlexMap detector. The fluorescent Luminex signal for barcoded A549 cells (mean ± S.E.M., n = 4) is directly proportional to the number of cells.

b. Relative inhibition profiles of erlotinib, NVP-TAE-684, and puromycin in a mixture of 25 barcoded lung adenocarcinoma cell lines (non-small cell lung carcinoma, NSCLC) in mixture. Twenty-five barcoded lung adenocarcinoma cell lines were tested in mixture against varying concentrations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor erlotinib or the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitor NVP-TAE-684 (at 0–10 μM) or the ribosomal inhibitor puromycin (at 0–10 μg/ml) and viability relative to DMSO-treated control is plotted as a color gradient. Cell lines are listed with bracketed barcode numbers. EML4-ALK, cell lines containing EML4-ALK translocations; EGFR mut, cell lines containing EGFR mutations. See text for details.

c. Area under the curve comparisons of cell viability measures with PRISM. Three methods were used to determine cell viability after subjecting 100 human cancer cell lines (representing 18 tissues of origin)—either individually (ATP using CellTiter-Glo, or Nuclei using Opera) or in 4 mixtures of 25 cell lines (PRISM)—to 23 antitumor compounds at 8 concentrations. The AUC (Area Under the Curve) for the viability vs. log(concentration), scaled to 1 (=100% viability over all concentrations), was determined for each cell line–compound combination for each method by taking the mean viability across all tested concentrations, and pairwise correlations between the methods are shown. Pearson correlation of ATP vs. Nuclei (left panel) r = 0.80, p < 0.0001; ATP vs. PRISM (center) r = 0.66, p < 0.0001; Nuclei vs. PRISM (right) r = 0.72, p < 0.0001.

d. Relative tumor cell line growth in mixture in animals. PRISM was used to quantitate barcode signals from tumors in 10 erlotinib- and 10 vehicle-treated animals. Tumor barcode signals were scaled first to corresponding barcode signals of the injected cell mixture to determine the number of cell equivalents; the scaled signal for each barcode line was then used to determine the percentage contribution of each tumor cell line to the mixture. The same 23 of 24 lines were detected in all 10 vehicle-treated animals. Circles denote mean percentage tumor volume; error bars denote standard error of the mean across 10 animals in each group.

e. EGFR mutation status and response to erlotinib in animals. Within tumors, EGFR mutation in cell lines was associated with a significant decrease in relative cell number (log ratio of percentage of tumor of each cell line in erlotinib-treated over vehicle-treated) compared to wt EGFR in cell lines (two-sided two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, D = 0.84, p = 0.0079). Median ± interquartile ranges are shown for each group.

We next treated a pool of 25 lung adenocarcinoma cell lines with compounds known to have genotype-specific patterns of killing. To account for different doubling times of cell lines, each compound-treated cell line was compared to vehicle-treated controls to compute the relative growth inhibition of each line. Whereas treatment with puromycin resulted in uniform killing across the pool (Fig. 2b), treatment with the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib resulted in the dose-dependent killing of the 4 EGFR-mutant cell lines in the pool, concordant with previous studies2 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 1). Similarly, another expected pattern of cell killing12 was observed with the ALK kinase inhibitor NVP-TAE-684 (Fig. 2b): the NCI-H3122 cell line, harboring an EML4-ALK translocation, was sensitive to the drug, whereas NCI-H2228, with a different EML4-ALK translocation, exhibited intrinsic resistance

To further test the ability of PRISM to recapitulate results observed in traditional cell line experiments, we created a panel of 100 barcoded cell lines comprising 18 lineages and challenged these in 4 pools of 25 cell lines with each of 43 anticancer compounds (including both targeted and cytotoxic agents), yielding 3,200 measurements per compound (Supplementary Table 1). We saw no evidence of PRISM performance varying as a function of tumor type or cell lineage, although larger panels of cell lines would be required to exclude this definitively. As expected, PRISM revealed similar patterns of activity across the 100 lines among functionally related compounds (e.g., microtubule binders, topoisomerase inhibitors, or MEK inhibitors; Supplementary Fig. 2a). For 23 compounds, we had access to sensitivity data across the same 100 cell lines measured by others in individual cell line assays measuring either ATP content (using CellTiter-Glo) or enumeration of cell nuclei (using an optical fluorescent imaging method, Opera)3, 13.

Using Area Under the Curve (AUC) as a measure, the traditional ATP and Nuclei readouts yielded similar global patterns of sensitivity (Pearson r = 0.80, p < 0.0001). PRISM yielded similar levels of global correlation (r = 0.72 compared to Nuclei, p < 0.0001; r = 0.66 compared to ATP, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 2). We note that the slightly stronger correlation between PRISM and Nuclei is expected because PRISM and Nuclei both represent direct readouts of cell number, whereas ATP measurement reflects a combination of cell number and metabolic activity.

For example, PRISM and Nuclei similarly identified hypersensitivity of BRAF-mutant melanoma cell lines to the BRAF inhibitor PLX4720 (Supplementary Fig. 2b). No significant differential sensitivity was seen to the RAF inhibitor sorafenib, now known to be only a weak inhibitor of the BRAF kinase1, 14 (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Similarly, PRISM detected a trend (p = 0.054) between BRAF mutation and sensitivity to the MEK inhibitor AZD6244 (acting immediately downstream of BRAF), findings consistent with clinical activity in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma15 (Supplementary Fig. 2b). PRISM and traditional methods yielded concordant results for 21/23 of compounds tested (91%), but two drugs (topotecan and paclitaxel) showed slightly discordant results (Supplementary Fig. 3). Whether these exceptions arise from the 3-day (Nuclei) vs. 5-day (PRISM) assay periods remains to be determined.

We next asked whether the PRISM approach could be extended to the in vivo setting, where the ability to multiplex cell lines in a single xenotransplant might accelerate translational research. One theoretical concern was that a small number of cell lines within a pool might rapidly overtake the others in vivo. To test this, we injected a pool of 24 barcoded lung adenocarcinoma cell lines subcutaneously into each of 10 recipient NSG (NOD-SCID-IL2Rgammanull) mice. Several weeks later, the mice were sacrificed and the tumors resected. Notably, PRISM detected 23/24 cell lines (96%) in each of 10 vehicle-treated mouse tumors. The 23 detectable lines grew at different rates, but their relative abundances within the tumors were nearly identical across the 10 vehicle-treated xenografts (Fig. 2d). Similarly, we sampled four different portions of each tumor, and found little variation in the contribution of particular cell lines in different parts of the tumor (e.g., Supplementary Fig. 4). An aliquot of the initial mixture of cell lines used for injection was also passaged weekly in vitro for three months. As with the in vivo experiments, the vast majority of the initial cell lines were detectable after 98 days in culture, and the abundance of each line remained stable over time (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results suggest that despite differences in growth rates, cell mixtures may reach an equilibrium state.

Next, we investigated whether PRISM could detect the expected sensitivity of EGFR-mutant cell lines when treated with erlotinib in vivo. Cohorts of 10 mice each were treated daily for 16 days by gavage with erlotinib vs. vehicle. Erlotinib treatment caused a marked reduction in relative abundance of 4/4 EGFR-mutant lines (by 22%, 88%, 75%, and 76%), while the 15/19 detectable wild-type EGFR lines were either minimally affected or increased in proportional abundance (Fig. 2d). As a group, mutant EGFR lines were significantly different from wild-type EGFR lines (Kolmogorov-Smirnov D = 0.84, p = 0.0079; Fig. 2e). Notably, the EGFR-mutant line showing the smallest in vivo response to erlotinib (HCC2935) was also less sensitive to erlotinib in vitro (cf. Fig. 2b). These experiments demonstrate the feasibility of PRISM to assess drug sensitivity in vivo.

We next examined whether PRISM could be used not only to elucidate the differential cytotoxic activity of optimized compounds (drugs) but also to discover new anti-cancer agents. We tested 102 barcoded lines (90 non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma (NSCLC) lines plus 12 lines of other lineages; Supplementary Table 2). The 102 cell lines, assayed in 4 pools of 25–27 cell lines, were screened against a library of 8,000 small molecules created using Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS)16-18 and 400 tool compounds or oncology drugs with known mechanism of action19.

This large dataset allowed systematic evaluation of the PRISM assay performance. Nearly all of the 102 cell lines yielded sufficient signal for drug sensitivity analysis (Strictly Standardized Mean Difference20; Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7), despite a > 10-fold signal range across the panel at baseline (Supplementary Fig. 6c). While the determinants of cell line signal are likely multifactorial, we did observe a correlation with proliferation rate (Supplementary Fig. 6d), suggesting that future assays could benefit from pooling based on cell doubling times.

As expected, many of the oncology drugs and optimized tool compounds displayed activity against cell lines (Supplementary Table 3; Supplementary Fig. 7). Furthermore, compounds with the same mechanism of action displayed markedly similar activity profiles across the cell line panel (Supplementary Fig. 8). Similarly, cell lines labeled with different barcodes and assayed in different pools showed similar patterns of compound activity, again reflecting PRISM robustness (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 3).

This large dataset also allowed us to assess the ability of PRISM to reveal genotype-phenotype relationships. Expected relationships between drug sensitivity and molecular features of the cell lines (from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia13) were indeed observed in genome-wide analyses (Supplementary Table 5). For example, sensitivity to nutlin-3 (designated BRD-A12230535), an inhibitor of the MDM2-TP53 interaction, was most strongly inversely correlated to the gene expression level of MDM2 (Spearman r = −0.66, p < 10−5). Erlotinib sensitivity demonstrated a strong inverse correlation with both EGFR gene expression (r = −0.61, p < 10−5) and EGFR gene copy number (r = −0.52, p = 2 × 10−5). Sensitivity to gefinitib (another EGFR inhibitor) showed similar correlations to EGFR gene expression and copy number (r = −0.51, p < 10−6 and r = −0.54, p < 10−6, respectively). These results suggest that beyond the well-recognized effect of EGFR mutation on conferring EGFR inhibitor sensitivity, EGFR expression and copy number may represent subtle determinants of sensitivity that are only revealed when large panels of cell lines are examined. As a community resource, gene expression and copy number correlates to sensitivity of the 370 reference compounds that showed PRISM activity are shown in Supplementary Table 5.

We next turned to the results of the 8000 DOS compounds screened against 102 cell lines. One hundred ninety-nine of the DOS compounds (2.5%) scored as hits in the primary screen (defined as at least one cell line being inhibited > 80% relative to control) and 139/199 (69.8%) compounds validated in a 8-point PRISM dose-response assay (Supplementary Table 6). Of the 139 compounds, 49 (24.5%) killed >70% of the cell lines, suggesting that they were non-specific cytotoxic agents. One of the 90 selective compounds, BRD-7880, was examined in greater detail.

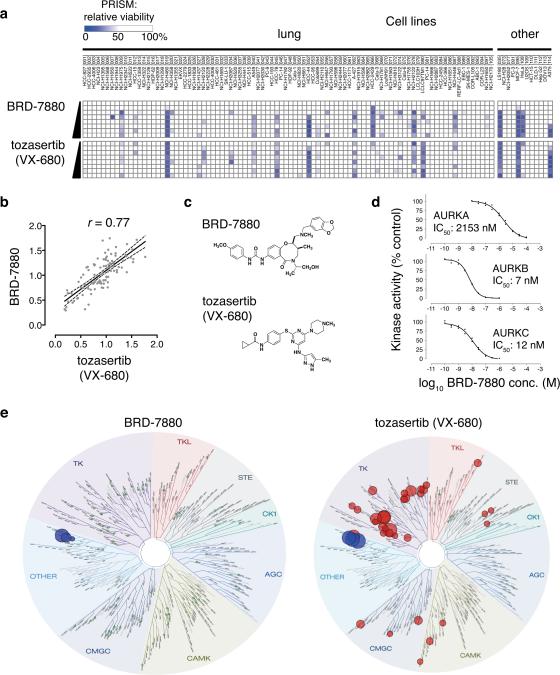

First, we asked whether the PRISM sensitivity profile across 102 cell lines could be used to gain insight into BRD-7880's mechanism of action by comparing its sensitivity profile to those of 400 tool compounds profiled in these same lines. BRD-7880 showed markedly similar activity to the aurora kinase inhibitor tozasertib (VX-680; Spearman r = 0.77, Figs. 3a and 3b, Supplementary Table 7), suggesting that despite the lack of structural similarity between the two compounds (Fig. 3c), BRD-7880 might be an aurora kinase inhibitor. Treatment of HCT-116 cells with BRD-7880 resulted in polyploidy (Supplementary Fig. 10a) and decreased phosphorylation of serine-10 in histone H3 (Supplementary Fig. 10b), supporting its functioning as an inhibitor of aurora kinase B (AURKB)21-23.

Figure 3. BRD-7880 inhibits aurora kinase B.

a. Comparison of PRISM profiles across 102 cell lines for BRD-7880 (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 μM) or tozasertib (0.07, 0.13, 0.26, 0.52, 1, 2, 4, 8 μM).

b. Correlation of PRISM AUC between BRD-7880 (a.k.a. BRD-K01737880) and tozasertib. Area under the curve (AUC) of viability vs. concentration curve was calculated for each cell line across 8 doses of compound. Least-squares (ordinary fit) regression line is shown with 95% confidence bands. Spearman r = 0.77.

c. Structures of BRD-7880 and tozasertib.

d. In vitro aurora kinase assays. Incorporation of radioactivity from 10 μM γ-33P-ATP was measured in in vitro kinase assays across 8 doses in duplicate by the EMD Millipore KinaseProfiler service under published standard conditions with 10 mM ATP. Full-length human AURKA was assayed with 200 μM LRRASLG (Kemptide); full-length human AURKB with 30 μM AKRRRLSSLRA (ribosomal protein S6 peptide); and full-length human AURKC with 30 μM AKRRRLSSLRA. IC50 values were modeled using least-squares and variable slope with GraphPad Prism 6.0 software.

e. KinomeScan profile for BRD-7880 across 98 kinases. Left, schematic representation of relative affinity of BRD-7880 for specific kinases in the KinomeScan assay (data available in Supplementary Table 9). Green circles represent tested kinases for which BRD-7880 decreases binding < 75% control. Right, published relative affinities of tozasertib (VX-680) for same 98 kinases (where available 26, 27).

Biochemical kinase activity assays showed that BRD-7880 is indeed a potent inhibitor of AURKB and AURKC (IC50 of 7 nM and 12 nM, respectively) with less activity against AURKA (IC50 = 2153 nM) (Fig. 3d), a profile resembling that of barasertib (AZD1152-HQPA; Supplementary Fig. 11). Kinetic measurements of in vitro AURKB activity suggested that BRD-7880 functions in an ATP-competitive manner (Supplementary Fig. 12). To assess the specificity of BRD-7880, kinase activity profiling was performed for 308 kinases, and this analysis showed that BRD-7880 is far more selective than tozasertib, substantially inhibiting (to < 25% control activity) only AURKB and AURKC (Supplementary Table 8). Similarly, in a screen of kinase-binding selectivity across 98 kinases BRD-7880 shows highly specific binding to AURKB and AURKC (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Table 9). We are unaware of any other aurora kinase inhibitor with this degree of specificity. The result also demonstrates the utility of PRISM for rapidly identifying a molecular target: the target of BRD-7880 was revealed simply by virtue of its pattern of activity across a large panel of cell lines. Such activity would not have been obvious had the compound been tested on only a small number of cell lines.

PRISM will facilitate oncology drug discovery by making it feasible to rapidly test chemical analogs across an entire cell line panel, thus assuring that the expected on-target pattern of activity is retained. The facile expansion of a single vial of pooled, barcoded cells provides a practical solution for extending traditional compound screening to hundreds of individual cell lines. Furthermore, our demonstration of the feasibility of using PRISM in vivo suggests that cost-effective xenograft studies are possible. The bead-based barcode quantitation method used here has proven reliable and inexpensive, but further cost reductions will likely be achievable with massively parallel sequencing.

Most importantly, PRISM may facilitate cancer therapeutic discovery. Entire small-molecule libraries could be screened across large panels of cell lines, and compounds selected for their differential killing (e.g., selectively killing cells harboring “undruggable” targets). We believe that the cancer research community would benefit from the creation of thousands of genetically characterized, barcoded cell lines. With such a resource, large-scale testing of compounds across the diversity of human cancer types could become a routine activity.

Methods Summary

Lentiviral barcoding vector

A 6.4 kb MluI-ClaI fragment was isolated from pLenti6.2/V5DEST (Invitrogen) and ligated to a linker comprising oligonucleotides 5'-CGATAACTGCAGAACCAATGCATTGGA-3' and 5'-CGCGTCCAATGCATTGGTTCTGCAGTTAT-3'. A library of MluI-PstI linkers was constructed using 24-bp Luminex DNA barcodes9 placed within oligonucleotides 5'-CGCGTXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXCTGCA-3' and 5'-GxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxA-3', where XXX...XXX includes the sense barcode sequence and xxx...xxx includes the antisense barcode sequence, and each of these linkers was individually ligated into the MluI-PstI backbone of the above vector to generate lentiviral barcoding plasmids. Lentivirus was generated from lentivral barcoding plasmids as previously described24 using pCMV-dR8.2 dvpr and pCMV-VSVG packaging vectors in FuGENE6-transfected (Roche Corporation) HEK-293T cells; viral supernatant was collected after 72h, passed through a sterile 0.45μm syringe filter (VWR cat. 28144-007), and stored at −80°C.

Cell lines

Cell lines were obtained through the American Type Culture Collection or provided by the Broad-Novartis Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia3 and cultured in HEPES-buffered RPMI medium (ATCC cat. 30-2001) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma cat. F5410) and penicillin/streptomycin G (Invitrogen cat. 10378-016). Drug sensitivity data of CCLE cell lines was obtained from http://www.broadinstitute.org/ccle.

Barcoding of tumor cell lines

Barcode-containing lentivirus was used to infect human tumor cell lines at 1:20 dilution with sham-infection controls. The following day, virus was removed and media was replaced by fresh media containing blasticidin (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 3–10 μg ml−1 media in both virally infected and sham-infected cells. Culture in blasticidin-containing media was continued in infected and sham-infected cells for 2–4 weeks until no sham-infected cells survived. Barcoded lines were frozen individually and later frozen as defined pools.

SNP fingerprinting of cell lines

For cell line identity confirmation, we utilized 4 HX Fluidigm IFC chip loaders and 4 FC1 cyclers for the 96.96 dynamic array. The reference set of SNP genotypes was derived from the Affymetrix SNP6.0 array Birdseed genotypes from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE)3,25. Birdseed genotypes for 42 SNPs were used as references for cell line identity. Fingerprints (genotypes for those same SNPs) assayed by Fluidigm after screening were extracted and compared to the reference set of SNPs across all CCLE lines, using the GenePattern FPmatching module at http://genepattern.broadinstitute.org/gp/.

PRISM compound assays

Frozen mixtures containing randomly chosen assortments of 25 to 27 barcoded cell lines were thawed (day −2) and replated (day −1) into 384-well microtiter plates at 50 cells per cell line per well. On day 0, compounds suspended in DMSO were pinned into cultures to achieve 8 to 16 concentrations. On day 5, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and lysed for 60 minutes at 60°C in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mM KCl, 0.45% IGEPAL CA-630 (Sigma cat. I8896), 0.45% Tween-20 (Sigma cat. P9416), and 10% proteinase K (Qiagen cat. 19133). Proteinase K was inactivated by a 15-minute incubation at 95°C.

PRISM detection

Detailed protocols of the PRISM method are available in Supplementary Methods. Genomic DNA from cell lysates was amplified by PCR using primers Biotin pLENTR4 (5’-Biotin-CGTCATTACTAACCGGTACGC-3’) and pLENTF1 5’-GGAATAGAAGAAGAAGGTGG-3’. PCR product was hybridized to Luminex beads with covalently attached antisense barcodes, and streptavidin-phycoerythrin addition, washing, and detection on Luminex FlexMap machines was performed as previously described9. PCR without genomic DNA was hybridized with beads to serve as background control; signal for each bead was subtracted from each sample measurement. DMSO-treated cell mixtures were used as reference control for scaling of each cell line signal at the conclusion of each experiment (viability = 100 for each cell line). Thus the signal from each treated cell line was calculated as 100 × [(median Luminex measurement across replicates) – (median Luminex measurement of no DNA control)] / (median Luminex measurement of DMSO control).

In vivo PRISM

Barcoded cell lines grown in tissue culture were mixed in equal numbers. 2.4 × 107 cells of this mixture (i.e., 1 × 106 cells from each of 24 cell lines) were injected subcutaneously into each of 20 six-week-old male and female immunodeficient NOD SCID gamma (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ) Mus musculus (Jackson Laboratories #005557) under animal use protocol #04-111, which was reviewed and approved by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Animal Care and Use Committee. Two unrandomized but identical groups of animals with ten animals per group were chosen to detect a 50% reduction in the proportion of a given cell line within a tumor, based on a mean proportion of 4.17% (100% ÷ 24 cell lines) and standard deviation of 1.5%, alpha = 0.05. Mice were treated once daily for 16 days by gavage with either the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib (50 mg kg−1 body weight) or vehicle control (1% sodium carboxymethyl cellulose), beginning 12 days following injection of the cell lines. The tumors were resected, each tumor was cut into four portions, and the relative abundance of each cell line in each portion was unblindedly determined by PRISM: for each sample, the fluorescent signal for each cell line was converted to cell number using the signal from the cell mixture used for injection, and these cell numbers were used to calculate the relative contribution of each cell line to the tumor.

Correlation of PRISM profiles with genomic features

PRISM viability measurements in cell lines verified to be identical to Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia lines using SNP fingerprint analysis were used as profiles to query previously reported genome-wide features (gene expression and copy number) of cell lines in the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia13. Among the pairs of duplicate cell lines, the cell line with the higher baseline PRISM signal was selected for genomic correlation analysis. Three cell lines which showed markedly decreased baseline signals in control wells (COR-L23 [094], NCI-H2228 [029], and NCI-H661 [051]) were excluded from correlation analyses. Spearman's rank correlation was computed using the PRISM AUC measurement from each compound versus either gene expression or copy number, and the significance of correlation was calculated using permutation testing with 106 iterations. All genomic data for these cell lines are available at http://www.broadinstitute.org/ccle.

In vitro kinase inhibition assays

Incorporation of radioactivity from 10 μM γ-33P-ATP was measured in in vitro kinase assays across 8 doses in duplicate by the EMD Millipore KinaseProfiler service (Billerica, MA) under published standard conditions with 10 mM ATP. Full-length human AURKA was assayed with 200 μM LRRASLG (Kemptide); full-length human AURKB with 30 μM AKRRRLSSLRA; and full-length human AURKC with 30 μM AKRRRLSSLRA. IC50 values were modeled using least-squares and variable slope with Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

KinaseProfiler profiling

Specificity of in vitro kinase inhibition by BRD-7880 (30 nM) or tozasertib (30 nM) was performed by EMD Millipore (Dundee, United Kingdom) using standardized protocols.

KinomeScan profiling

Kinase binding was performed by DiscoveRx (Fremont, CA) using their KinomeScan method, using the scanEDGE profile (97 kinases) plus the inclusion of AURKC (total 98 kinases). Images were generated using TREEspot™ Software Tool and reprinted with permission from KINOMEscan, a division of DiscoveRx Corporation.

AURKB in vitro kinase assays

Enzyme kinetic experiments were performed at pH 7.0 in 8 mM MOPS buffer with 0.2 mM EDTA and 10 mM magnesium acetate. Reactions were assembled in 384-well plate wells by adding 400 ng/ml of AURKB (EMD Millipore cat. no. 14-835) into separate reaction mixtures containing 1.5μM fluorescently labeled Caliper peptide substrate (FL-peptide 1, 5-FAM-AKRRRLSSLRA-COOH, Perkin-Elmer cat. no. 760345) with various concentrations of ATP and compound (BRD-7880, tozasertib, barasertib). The final ATP concentrations varied from 6.25 to 200 μM and compound varied from 0 to 200 nM. Plates were immediately placed into a Perkin-Elmer Caliper LabChip EZ Reader and wells were sampled periodically throughout a 1-hour reaction period for initial reaction rate. The fluorescent product and substrate were separated and monitored on the Caliper microfluidic instrument. The conversion of substrate was calculated with Caliper software. Km and ki values were determined from the double reciprocal Lineweaver-Burk plot by linear regression with GraFit 6 software (Erithacus Software Ltd., Horley, U.K.) using competitive inhibition equation modeling.

DNA content analysis

HCT-116 cells were treated with 10 μM of DMSO, barasertib, GSK1070916, MLN8054, BRD-7880, or tozasertib. 24 hours or 48 hours following treatment, cells were stained with propidium iodide and DNA content per cell was assessed using a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Western blotting

HCT-116 cells were treated with 10 μM of DMSO, barasertib, GSK1070916, MLN8054, BRD-7880, or tozasertib. Cells lysates were probed on Western blot using antibodies (diluted 1:1000) to histone H3 (Abcam cat. 24834), phosphoserine10-histone H3 (Cell Signaling Technology cat no. 3377SS), aurora kinase B (Millipore cat. no. 04-1036), or beta-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology cat. no. sc-47778) and detected using a LI-COR Odyssey analyzer (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sungjoon Kim, Ghislain Bonamy, Jianwei (John) Che, Joseph Thibault, Truc Huynh, Ingo Engels, and Aaron Shipway at Novartis for sharing data prior to publication; Amanda Christie and Tina Davis for technical assistance in animal studies; Catherine Hartland, Scott Donovan, Elizabeth Rubin, and Ellen Winchester for technical assistance in compound assays; Joshua Bittker, John McGrath, and Greg Wendel for assistance in compound management; Sebastian Le Quement and Jeremy Duvall for assistance in compound synthesis; Jennifer Gale for technical assistance in enzyme kinetic assays; Sara Howell for assistance in curation of computational datasets; Angela Koehler, Sivaraman Dandapani, Benito Muñoz, Christina Scherer, Daniel Gray, Daniel Bachovchin, Stefano Santaguida, and Jonathan Elkins for expert scientific guidance; Jordi Barretina, Nicolas Stransky, Sebastian Nijman, Bina Julian, Willis Read-Button, John Davis, and David Peck for technical advice; and members of the Golub laboratory for critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Genomics Based Drug Discovery consortium grants RL1-CA133834, RL1-GM084437, and UL1DE019585 (administratively linked to NIH Grant RL1-HG004671), National Cancer Institute Integrative Cancer Biology Program grant U54CA112962, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Claudia Adams Barr Program in Cancer Research Innovative Basic Science Research Program Grant, the American Society of Clinical Oncology Conquer Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award, and the Prostate Cancer Foundation.

Footnotes

Author Contributions. C.Y. and T.R.G. designed the PRISM method and wrote the manuscript. C.Y., G.M.Y, and A.M.M. performed the experiments in the study. L.A.G. provided cell lines and drug response validation data from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia Project. B.A.W. performed cell line genotype verification analyses. K.N.R. and P.T. contributed to statistical analyses of PRISM validation data. J.Z.G. and C.Y. created data processing and data visualization tools. M.A.P.,W.W., A.C.,M.A.M., B.R.T.,G.M.Y,A.M.M., and C.Y. performed the large-scale PRISM screen. A.T. and C.Y. performed genomic correlation analyses in the large-scale PRISM screen. A.F.S. and S.L.S. contributed to compound creation and curation and design of experiments with BRD-7880. Y.-L.Z. performed kinetic kinase inhibition experiments with BRD-7880. A.L.K.,C.Y., and T.R.G. contributed to design and execution of in vivo PRISM experiments. B.W. contributed to data visualization tools and to manuscript figures. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests Statement.

C.Y. and T.R.G. are inventors in patent application PCT/US2013/031312.

References

- 1.McDermott U, et al. Identification of genotype-correlated sensitivity to selective kinase inhibitors by using high-throughput tumor cell line profiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19936–19941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707498104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sos ML, et al. Predicting drug susceptibility of non-small cell lung cancers based on genetic lesions. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1727–1740. doi: 10.1172/JCI37127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barretina J, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garnett MJ, et al. Systematic identification of genomic markers of drug sensitivity in cancer cells. Nature. 2012;483:570–575. doi: 10.1038/nature11005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma SV, Haber DA, Settleman J. Cell line-based platforms to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of candidate anticancer agents. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2010;10:241–253. doi: 10.1038/nrc2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abaan OD, et al. The Exomes of the NCI-60 Panel: A Genomic Resource for Cancer Biology and Systems Pharmacology. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4372–4382. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basu A, et al. An interactive resource to identify cancer genetic and lineage dependencies targeted by small molecules. Cell. 2013;154:1151–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner NC, Reis-Filho JS. Genetic heterogeneity and cancer drug resistance. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e178–185. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peck D, et al. A method for high-throughput gene expression signature analysis. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R61. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-7-r61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du J, et al. Bead-based profiling of tyrosine kinase phosphorylation identifies SRC as a potential target for glioblastoma therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:77–83. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muellner MK, et al. A chemical-genetic screen reveals a mechanism of resistance to PI3K inhibitors in cancer. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:787–793. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koivunen JP, et al. EML4-ALK fusion gene and efficacy of an ALK kinase inhibitor in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4275–4283. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. http://www.broadinstitute.org/ccle.

- 14.Wilhelm SM, et al. Preclinical overview of sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that targets both Raf and VEGF and PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3129–3140. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flaherty KT, et al. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:107–114. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Comer E, et al. Fragment-based domain shuffling approach for the synthesis of pyran-based macrocycles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6751–6756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015255108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowe JT, et al. Synthesis and profiling of a diverse collection of azetidine-based scaffolds for the development of CNS-focused lead-like libraries. J Org Chem. 2012;77:7187–7211. doi: 10.1021/jo300974j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcaurelle LA, et al. An aldol-based build/couple/pair strategy for the synthesis of medium- and large-sized rings: discovery of macrocyclic histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:16962–16976. doi: 10.1021/ja105119r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schreiber SL, et al. Towards patient-based cancer therapeutics. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:904–906. doi: 10.1038/nbt0910-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang XD. Illustration of SSMD, z score, SSMD*, z* score, and t statistic for hit selection in RNAi high-throughput screens. Journal of biomolecular screening. 2011;16:775–785. doi: 10.1177/1087057111405851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrews PD, Knatko E, Moore WJ, Swedlow JR. Mitotic mechanics: the auroras come into view. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:672–683. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carmena M, Earnshaw WC. The cellular geography of aurora kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:842–854. doi: 10.1038/nrm1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ditchfield C, et al. Aurora B couples chromosome alignment with anaphase by targeting BubR1, Mad2, and Cenp-E to kinetochores. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:267–280. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. http://www.addgene.org/static/data/70/82/1619d3c0-af64-11e0-90fe-003048dd6500.pdf.

- 25.Korn JM, et al. Integrated genotype calling and association analysis of SNPs, common copy number polymorphisms and rare CNVs. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1253–1260. doi: 10.1038/ng.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis MI, et al. Comprehensive analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:1046–1051. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karaman MW, et al. A quantitative analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:127–132. doi: 10.1038/nbt1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.