Abstract

Cluster randomised trials have diminishing returns in power and precision as cluster size increases. Making the cluster a lot larger while keeping the number of clusters fixed might yield only a very small increase in power and precision, owing to the intracluster correlation. Identifying the point at which observations start making a negligible contribution to the power or precision of the study—which we call the point of diminishing returns—is important for designing efficient trials. Current methods for identifying this point are potentially useful as rules of thumb but don’t generally work well. We introduce several practical aids to help researchers design cluster randomised trials in which all observations make a material contribution to the study. Power curves enable identification of the point at which observations begin to make a negligible contribution to a study for a given target difference. Under this paradigm, the number needed per arm under individual randomisation gives an upper bound on the cluster size, which should not be exceeded. Corresponding precision curves can be useful for accommodating flexibility in the choice of target difference and show the point at which confidence intervals around the estimated effect size no longer decrease. To design efficient trials, the number of clusters and cluster size should be determined concurrently, not independently. Funders and researchers should be aware of diminishing returns in cluster trials. Researchers should routinely plot power or precision curves when performing sample size calculations so that the implications of cluster sizes can be transparent. Even when data appear to be “free,” in the sense that few resources are needed to obtain the data, excessive cluster sizes can have important ramifications

Summary points

Cluster randomised trials have diminishing returns in power and precision as cluster size increases

In some situations a small increase in the number of clusters can lead to a large drop in the total number of observations needed for the same level of power

When the target effect size is the true minimally important difference, or the minimum plausible difference, cluster size should not exceed the number needed per arm under individual randomisation

Power calculations for cluster randomised trials should report the sample size required under individual randomisation

Plots of power or precision against cluster size enable identification of points beyond which further increases in cluster size make no material contribution to the study

To facilitate efficient trial design, the number of clusters and cluster size should be determined concurrently, not independently

Cluster randomised trials (CRTs) involve randomisation of groups (clusters) of individuals to control or intervention conditions.1 The CRT design is commonly used to evaluate non-drug interventions, such as policy and service delivery interventions. Its use is likely to grow as we move towards the learning healthcare system2 and large simple trials.3

In a CRT the total sample size is a function of both the number of clusters and cluster size. Invariably, one of these is fixed and the other is determined using published formulas.1 For example, the number of clusters available or feasible might be considered fixed and the necessary cluster size then determined.

The intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) measures the degree to which observations (that is, outcome measurements from participants) in a cluster are correlated. The need to account for the ICC when designing and analysing these trials is widely appreciated, but the effect of clustering on the choice of cluster size has received less attention. A CRT could be designed with an excessively large cluster size, such that not all observations in the cluster make a material contribution to the power or precision of the trial.

In this paper we examine the trade-offs that are made when determining the number of clusters and cluster sizes. We introduce methods that will enable researchers to design efficient CRTs and funders to appraise the efficiency of CRTs that they commission.

Diminishing returns

A unique characteristic of CRTs is that, as more individuals are recruited or data are accrued without increasing the number of clusters, the increase in power starts to level off.4 5 6 7 The point at which this happens—that is, when observations start making a negligible contribution—depends on key design characteristics, such as type of outcome, target difference, proportion of people with the outcome (for binary outcomes), and ICC. In studies with larger ICCs, each observation contributes less to the overall power than in studies with smaller ICCs. Furthermore, not only power reaches a plateau, but also the resulting precision. Power is the ability of a trial to detect a target effect size, whereas precision is its ability to measure the effect size with a sufficiently narrow confidence interval. This lessening in effective contribution can be considered “diminishing returns.”

How to identify the point of diminishing returns

Identifying the point at which increases in power or precision become negligible is not easy, because it occurs gradually. The point of diminishing returns cannot be identified definitively, but attempts to do so have led to simple rules of thumb. For example, some researchers have proposed that, for continuous outcomes, power does not increase appreciably when the number of participants in a cluster exceeds 1/ICC; others have proposed 2/ICC.8 9 10 In the examples that follow, however, we show that these rules of thumb tend to overestimate the point of diminishing returns for power when the ICC is low and underestimate it when the ICC is high. Moreover, these rules don’t accurately estimate the point of diminishing returns for precision.

Power and precision curves are more useful, enabling clear determination of the extent to which all observations contribute to the study. Power curves are plots of the power achievable as cluster size increases. These curves enable identification of the point at which observations start making no material contribution to a study for a given target difference. Trials are often designed to detect a minimally important effect size at a specified power. Under this paradigm, observations that make a negligible contribution are those beyond the point at which the power curve plateaus. Observations beyond this point might still contribute to precision. After the precision curve has reached its plateau, however, observations make negligible contributions (under the postulated design conditions). We have provided formulas for power and precision in a data supplement (Appendix 1), as well as Stata and R code (Appendix 2) to construct these curves. We have also provided an Excel calculator (details in Appendix 2).

How to identify an absolute upper bound for cluster size

Although increasing cluster size can reduce the required number of clusters up to a point, doing so beyond the sample size needed under individual randomisation does not reduce it further (Appendix 3). This means that the sample size needed for each arm under individual randomisation is the absolute upper bound for cluster size. For example, the sample size needed to detect a standardised effect size of 0.25 with 90% power using a two sided significance level of 5% is about 340 people in each arm under individual randomisation. If this target difference was the minimum that could plausibly be achieved by the intervention, or the minimum clinically important difference, then cluster sizes should not exceed 340. If target differences were smaller, then larger cluster sizes might be justifiable. For example, if effect sizes of 0.1 were plausible (needing about 2100 in each arm under individual randomisation), then cluster sizes should not exceed 2100. Although this upper bound is independent of the ICC, the point of diminishing returns is frequently obtained at much smaller cluster sizes than that needed under individual randomisation (for example if the ICC is very small).

How to determine whether a small increase in the number of clusters can substantially reduce cluster size

Data in Appendix 3 show that a simple rule can help determine whether a small increase in the number of clusters can lead to a much more efficient design. Firstly, the user needs to determine the minimum number of clusters needed to detect the desired effect size at the desired power (assuming an unlimited cluster size). This is simply n×ICC, where n is the sample size for each arm under individual randomisation.5 7 Increasing the number of clusters to one more than the minimum means that the required cluster size will be at most n/1; increasing the number of clusters to two more than the minimum means that the cluster size will be at most n/2; and so on. Although this won’t give the exact cluster size needed, this simple rule is a very useful guide to determining if the trial could be made more efficient, without resorting to extensive calculations.

How to design an efficient trial with a limited number of clusters and limited cluster size

Case study: the Group B streptococcus trial

As an example, we consider a recently funded CRT to assess the effectiveness of a new rapid test to diagnose Group B streptococcus infection at the time of labour. Hospitals are randomised to either the rapid test arm or the current standard of care, which consists of prophylactic antibiotics for all women with known risk factors. This results in a high rate of relatively untargeted prescribing. The aim of the trial is to determine whether the intervention can reduce the proportion of women who are prescribed antibiotics.

The number of clusters in the trial is limited by the number of rapid test machines, which are costly and are rented from the manufacturer. Minimising the number of clusters is preferable, but there is no exact limit. Furthermore, the outcome data are not routinely collected, so every observation accrued in each cluster is associated with additional cost.

About 60% of patients are estimated to receive prescriptions for prophylactic antibiotics, and an absolute risk reduction of about 15% is considered a clinically important effect size. Under individual randomisation, this would require a sample size of about 228 in each arm at 90% power and two sided significance level of 5% (see formula in Appendix 1). For a CRT, this sample size needs to be increased to account for the ICC. The estimated ICC is 0.03, a fairly typical value in CRTs.

We consider two common starting points for designing this trial. In the first approach the number of clusters is fixed, and we determine the required cluster size. We show how allowing some flexibility in the number of clusters can lead to a more efficient design. We then determine the required number of clusters when the cluster size is fixed. We show how inspecting power and precision curves can lead to a more efficient design.

Designing a trial when the number of clusters is fixed

Assuming that the 15% absolute risk reduction is the target difference, our simple rule says that the minimum number of clusters required for each arm is seven (228×0.03). With one more than the minimum (eight clusters in each arm), the cluster size should not exceed the number needed in each arm under individual randomisation (228). Increasing the number of clusters to nine (two more than the minimum) would make the cluster size less than 114 (228/2), and with 10 clusters in each arm, the cluster size would be less than 76 (228/3). This shows that, if resources and logistics allow, increasing the number of clusters by a small amount above the minimum could drastically reduce cluster sizes. These simple calculations are easily performed by hand (assuming knowledge of the number needed under individual randomisation) and could be used as a quick scrutiny assessment by a funding panel or reviewer.

The exact calculations are shown in Appendix 1. To achieve 90% power with seven clusters in each arm, cluster size should be 1383, yielding a total sample size of 19 362 (table 1). To achieve 80% power with the same number of clusters, the required cluster size is only 89, yielding a total sample size of 1246. Moreover, if the number of clusters were increased by two, to nine in each arm, then a cluster size of 103 would achieve 90% power (equating to a total sample size of 1854—a fraction of that required with for seven clusters in each arm). With 15 clusters in each arm, the cluster size required would be 28, giving a total sample size of 840.

Table 1.

Trade-off between number of clusters and cluster size for the case study

| No of clusters in each arm | 80% power | 90% power | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster size | Total sample size | Cluster size | Total sample size | |

| 6 | 191 | 2292 | NA | NA |

| 7 | 89 | 1246 | 1383 | 19 362 |

| 8 | 58 | 928 | 191 | 3056 |

| 9 | 43 | 774 | 103 | 1854 |

| 10 | 35 | 700 | 70 | 1400 |

| 11 | 29 | 638 | 54 | 1188 |

| 12 | 25 | 600 | 43 | 1032 |

| 13 | 22 | 572 | 36 | 936 |

| 14 | 19 | 532 | 31 | 868 |

| 15 | 17 | 510 | 28 | 840 |

Sample size needed to detect a difference between two proportions of 0.60 and 0.45 at two sided significance level of 5%, assuming normal approximations (formula in Appendix 1).

Assumes 228 in each arm needed for 90% power and 171 for 80% power.

ICC assumed to be 0.03.

Rounding has occurred at some levels.

NA=not achievable

These calculations show that decisions to restrict the number of clusters as far as possible should be made with knowledge of the implications for total trial size.

Designing a trial when the cluster size is fixed

Now we assume that the trial will run for about six months and that the cluster size is set as the number of women meeting the eligibility criteria over this period: about 400 women from each hospital or about 70 observations a month. The cluster size of 400 can be considered the maximum available for a given amount of funding or trial duration.

The required number of clusters must be determined for the fixed cluster size. Using the same absolute difference as above, a prespecified cluster size of 400 means we need eight clusters in each arm (equating to a total sample size of 6400). Based on our simple rule that cluster size should not exceed the number needed in each arm under individual randomisation (228), this would be an inefficient design (under the assumption that a 15% absolute risk reduction is the true minimum important difference).

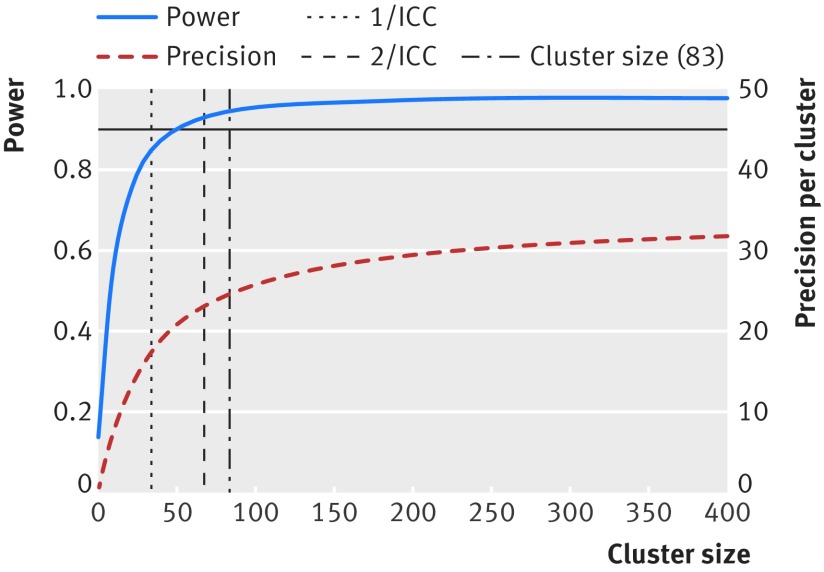

Figure 1 shows that for an ICC of 0.03 the increase in power becomes negligible at cluster sizes around 100. It also shows that increases in precision around the estimated treatment effect are almost non-existent for cluster sizes around 400. This tells us that, if the effect size (the difference between the control and treatment proportions) is the true target difference then the cluster size should not exceed 100 (equivalent recruitment duration of 1.5 months for each cluster). Supplementary figure 1 shows that cluster sizes above about 50 would not increase the power under the assumption of an ICC of 0.01; but that precision around the resulting treatment effect would still increase for cluster sizes up to 400. Supplementary figure 2 show how these decisions would change if the ICC were larger. These figures also show that the common rules of thumb (such as 1/ICC) for identifying upper bounds on the cluster size are not very useful.

Fig 1 Power and precision curves for case study with an ICC of 0.03. Curves show increases in power (blue line) and precision (red line) as cluster size increases. Assumes a CRT with 10 clusters in each arm, designed to detect a difference between two proportions 0.6 and 0.45 at a two sided significance level of 5%.

The calculations in this second approach show that, although the cluster size might be deemed to be fixed, these effectively ad hoc cluster sizes might be much larger than they ought to be. More efficient trials can be designed by acknowledging this possibility and graphically viewing the contribution each observation makes.

An efficient trial design for Group B streptococcus

The feasibility of running the Group B streptococcus trial was constrained by a need to limit the number of clusters. The trial was also limited by funding constraints that limited the resources that could be devoted to data collection. Subsequently, there was a need to limit the cluster size. With some flexibility to increase the number of clusters, it was decided to increase the number of clusters in each arm to 10—with cluster sizes of around 85 (to allow for a small loss of follow-up), equating to a total sample size of 1700—to retain a high power to detect smaller differences, which were also thought to be clinically important.

Design implications

How to deal with the practical constraints of limited numbers of clusters

Researchers have several options when faced with a limited number of clusters and an anticipated ICC that indicates very large cluster sizes may be required to reach the desired power. Our recommended option would be to increase the number of clusters, if possible. If not, then a decision has to be made between having a smaller cluster size and not achieving the desired power or having a potentially excessively large cluster size and achieving the desired power. This choice must be made on a trial by trial basis and will depend on the cost of data collection; the risks of the study to research participants also need careful consideration. The decision should be made with full awareness of the contribution that each observation is making, best visualised by a power or precision curve. We think that striving for a notional level of power (such as 90%, and thus rejecting a level of power of 80%) is akin to focusing on a dichotomy of statistical significance and should be discouraged.11

When to consider power and when to consider precision

Power and precision curves can be used to identify excessively large cluster sizes by showing the contribution of observations as the cluster size increases. Researchers are accustomed to considering trial power and are likely to be drawn to using power curves rather than precision curves. When the effect size used in the power calculation is the true minimally important difference, excessive cluster sizes should be identified by the point at which the power levels off. When smaller effect sizes might be clinically important and plausible, or target effect sizes less certain, then precision curves can identify the point at which observations will begin to make no material contribution, however small the effect size.12 These curves can be produced for all types of outcomes (continuous, binary, rates) and for different analysis types (interim analyses and non-inferiority). For binary outcomes, the precision curve is dependent not only on the target difference but also the control proportion.

How to ensure all data are put to good use

In some situations, trials can be made more efficient by choosing a shorter duration or sampling outcomes from a subset of available participants. But sometimes increased numbers are without added burden—for example, where data are routinely collected—or it may be counterintuitive to sample observations if the expense or logistics of setting up the intervention is high.

In these situations full knowledge of the point of diminishing returns could enable prespecified subgroup effects to be fully powered or the trial could be designed with more than one primary outcome with the necessary multiplicity adjustments. Information from observations above the point of material contribution could be redirected to other analyses. Knowledge of these diminishing returns might be helpful at the interim analysis stage, especially if the trial poses burden or risk to participants.

Other practical considerations

Another important consideration is that the point of diminishing returns depends on the ICC, which may not be reliably estimated at the design stage. Obtaining a good point estimate of the ICC is often difficult, but generic information of the type of outcome (clinical or process) and the size of the cluster can help.13 14 When the outcomes are from routinely collected data, good point estimates of the ICC can sometimes be obtained in advance of the trial. In the Group B streptococcus trial, if the ICC was higher than 0.03, cluster sizes greater than 85 would risk making negligible contributions; if it were lower, then larger cluster sizes might have added information.

In addition to considering power and precision at the planning stage, appropriate consideration should be given to whether the number of clusters, if small, is adequate to enable the appropriate analysis models to be fitted and to ensure that the trial does not risk the possibility of a chance imbalance.15

Other designs, such as the cluster-crossover, might not have the same degree of diminishing returns as the parallel design; the cluster-crossover design is highly efficient and should be considered when bidirectional designs are feasible.16 Rather than reducing the duration of a study to avoid excessive cluster sizes, researchers should consider using a longitudinal design: by breaking up the total trial duration (and, thus, the total cluster size) into a series of repeated measures, the required number of clusters may be substantially reduced.16

Limitations

We have focused on the number of clusters and the number of observations in each cluster. We have mentioned financial costs, but not considered them directly. Nor have we considered costs to society and the ethical implications for participants. When faced with a costly intervention, researchers could consider using unequal allocation ratios; we have focused on designs with 1:1 allocation ratios and have not examined power or precision curves in the case of unequal allocation. Finally, our sample size formulas assumed a relatively large number of clusters; when the number of clusters is small, it is commonly recommended to add one cluster to each arm in the case of a 5% significance level to account for the use of critical values from the normal, rather than the t, distribution.4

Conclusions

Decisions about the number of clusters and the cluster sizes should be made concurrently, not independently. Funders should carefully consider whether striving for a notional level of power (such as 90%) is good use of public money and should encourage researchers to show that their cluster trial has been designed so that all observations make a material contribution.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Appendices 1-3: Appendix 1—Formula and notation; Appendix 2—Illustration of how to construct power and precision curves; Appendix 3—Derivation of a simple rule to determine if a minimal increase in the number of clusters can lead to a significant reduction in cluster size.

Supplementary figures: Power and precision curves for case study for ICCs of 0.01 and 0.05

Contributors: KH conceived the idea, led the writing of the manuscript, and produced the figures. MT co-led the writing and development of ideas with KH. GF and SE conceived the mathematical rule of thumb. GF and KH developed the Stata code. CW made important contributions to all aspects of the paper. All authors contributed to writing, drafting and editing the paper. KH is guarantor.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to care.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Eldridge S, Kerry S. Introduction. In: A practical guide to cluster randomised trials in health services research.John Wiley and Sons, 2012. 10.1002/9781119966241.ch1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus DC. Fusing randomized trials with big data: the key to self-learning health care systems?JAMA 2015;314:767-8. 10.1001/jama.2015.7762 pmid:26305643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peto R, Collins R, Gray R. Large-scale randomized evidence: large, simple trials and overviews of trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1995;48:23-40. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00150-O pmid:7853045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donner A. Some aspects of the design and analysis of cluster randomization trials. J R Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat 1998;47:95-113 10.1111/1467-9876.00100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donner A, Klar N. Statistical considerations in the design and analysis of community intervention trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:435-9. 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00511-0 pmid:8621994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guittet L, Giraudeau B, Ravaud P. A priori postulated and real power in cluster randomized trials: mind the gap. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:25 10.1186/1471-2288-5-25 pmid:16109162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hemming K, Girling AJ, Sitch AJ, Marsh J, Lilford RJ. Sample size calculations for cluster randomised controlled trials with a fixed number of clusters. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:102 10.1186/1471-2288-11-102 pmid:21718530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell MJ, Donner A, Klar N. Developments in cluster randomized trials and statistics in medicine. Stat Med 2007;26:2-19. 10.1002/sim.2731 pmid:17136746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell M, Walters SJ. How to design, analyse and report cluster randomised trials in medicine and health related research.Statistics in Practice Wiley, 2014. 10.1002/9781118763452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter B. Cluster size variability and imbalance in cluster randomized controlled trials. Stat Med 2010;29:2984-93. 10.1002/sim.4050 pmid:20963749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woolston C. Psychology journal bans P values. Nature 2015;519:9-10 10.1038/519009f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bland JM. The tyranny of power: is there a better way to calculate sample size?BMJ 2009;339:b3985. 10.1136/bmj.b3985 pmid:19808754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eldridge SM, Costelloe CE, Kahan BC, Lancaster GA, Kerry SM. How big should the pilot study for my cluster randomised trial be?Stat Methods Med Res 2016;25:1039-56. 10.1177/0962280215588242 pmid:26071431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell MK, Mollison J, Grimshaw JM. Cluster trials in implementation research: estimation of intracluster correlation coefficients and sample size. Stat Med 2001;20:391-9. pmid:11180309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taljaard M, Teerenstra S, Ivers NM, Fergusson DA. Substantial risks associated with few clusters in cluster randomized and stepped wedge designs. Clin Trials 2016;13:459-63. 10.1177/1740774516634316 pmid:26940696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hooper R, Bourke L. Cluster randomised trials with repeated cross sections: alternatives to parallel group designs. BMJ 2015;350:h2925 10.1136/bmj.h2925 pmid:26055828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendices 1-3: Appendix 1—Formula and notation; Appendix 2—Illustration of how to construct power and precision curves; Appendix 3—Derivation of a simple rule to determine if a minimal increase in the number of clusters can lead to a significant reduction in cluster size.

Supplementary figures: Power and precision curves for case study for ICCs of 0.01 and 0.05