Abstract.

During the past two decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the recognition and characterization of novel insect-specific flaviviruses (ISFVs). Some of these agents are closely related to important mosquito-borne flavivirus pathogens. Results of experimental studies suggest that mosquitoes and mosquito cell cultures infected with some ISFVs are refractory to superinfection with related flavivirus pathogens; and it has been proposed that ISFVs potentially could be used to alter the vector competence of mosquitoes and reduce transmission of specific flavivirus pathogens, such as dengue, West Nile, or Zika viruses. In order for an ISFV to be used in such a control strategy, the virus would have to be vertically transmitted at a high rate in the target vector population to insure its continued maintenance. This study compared the vertical transmission rates of an ISFV, cell fusing agent virus (CFAV), in two Aedes aegypti colonies: one naturally infected with CFAV and the other experimentally infected but previously free of the virus. CFAV filial infection rates in progeny of female mosquitoes from both colonies were > 90% after two generations of selection, indicating the feasibility of introducing an ISFV into a mosquito population. This and other considerations for evaluating the feasibility of using ISFVs as an arbovirus control strategy are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Cell fusing agent virus (CFAV) is the prototype of the insect-specific flaviviruses (ISFVs). CFAV was first isolated by Stollar and Thomas1 who observed that culture fluid from the Peleg line of Aedes aegypti cells,2 induced marked cytopathic effect with syncytium formation, when it was inoculated into a culture of Singh’s Aedes albopictus cells.3 Later studies4,5 demonstrated that this new agent, designated the “cell fusing agent,” was a novel member of the genus Flavivirus, family Flaviridae. Subsequently, CFAV has been detected in or isolated from field-collected mosquitoes worldwide, predominantly Ae. aegypti.6–12

The term “insect specific” refers to viruses that naturally infect hematophagous diptera (usually mosquitoes) and that replicate in mosquito cells in vitro, but do not replicate in vertebrate cells or infect humans or other vertebrates.13 This is in contrast to the classical arthropod-borne viruses of vertebrates (arboviruses) that are maintained principally, or to an important extent, through biological transmission between susceptible vertebrate hosts by hematophagous arthropods.14 The arboviruses are dual host (vertebrate and arthropod) viruses, whereas the insect-specific viruses appear to involve only a single host (hematophagous insects).

With advances in molecular tools for virus detection and the growing interest in mosquito microbiomes, there has been a recent explosion in the detection and description of new insect-specific viruses.13 As of November 2016, a total of 38 ISFVs have been reported.13,15–19 Undoubtedly, this number will continue to grow as more metagenomics analyses are done on mosquitoes and other hematophagous insects.

In view of the limited host range of the ISFVs, compared with the vertebrate pathogenic flaviviruses, one obvious question is, “how are the ISFVs maintained in nature?” The most likely mechanism is vertical transmission in their respective insect hosts. This hypothesis is supported by reports of the isolation of or detection of six ISFVs (CFAV, Aedes flavivirus, Calbertado, Culex flavivirus [CxFV], Kamiti River, and Spanish Ochlerotatus viruses) from adult male mosquitoes or from immature forms (eggs, larvae, or pupae).20 In addition, there is convincing evidence from both field and laboratory studies21,22 of vertical transmission of CxFV by Culex pipiens mosquitoes.

We recently described an established laboratory colony of Ae. aegypti that was persistently infected with CFAV.11 Subsequently, a series of experiments were carried out to 1) determine the efficiency of vertical transmission of CFAV in the naturally infected colony and 2) determine if we could introduce CFAV into female Ae. aegypti from a colony free of the virus, and if the experimentally infected females would also vertically transmit the virus to their offspring. This report describes our results.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mosquitoes.

Aedes aegypti from two established laboratory colonies (Galveston and Bangkok), maintained at the University of Texas Medical Branch, were used in these studies. The progenitors of the Galveston colony were collected as eggs and larvae in Galveston, Texas, in 2003 and have been maintained in continuous colony in our laboratory since that time.23 In 2012 while testing all of our laboratory mosquito colonies for the presence of mosquito-specific viruses, it was observed that the Galveston colony was persistently infected with CFAV.11 At the time, eight geographic strains of Ae. aegypti and Aedes albopictus were maintained in our insectary; but only the Galveston strain was found to be infected with the CFAV. The progenitors of the Bangkok Ae. aegypti colony were obtained from Bangkok, Thailand, in 2011; this colony is free of CFAV, as determined by culture in C6/36 cells, next-generation sequencing, and transmission electron microscopy.11

Mosquitoes were reared in an insectary, maintained at 27°C with 80% relative humidity and a 16-hour light/8-hour dark photoperiod, as described previously.24 Larvae were fed on Wardley shrimp pellets (Hartz Mountain Corp., Secaucus, NJ); adults were provided with cotton balls saturated with 30% sucrose solution.

Virus.

The strain of CFAV used in our experimental infections was originally isolated in a culture of C6/36 cells inoculated with a pool of 50 homogenized female Ae. aegypti from the Galveston colony.11 The NCBI Reference sequence for the isolate is NC-001564. The sample used to experimentally infect the Ae. aegypti females (Bangkok colony) had been passaged three times in cultures of C6/36 cells.

Infection of mosquitoes.

Approximately 100 female mosquitoes of the Bangkok Ae. aegypti colony were inoculated intrathoracically24 with approximately 0.15 uL of a C6/36 stock of CFAV (titer unknown). Infected mosquitoes were held in a 30.5 cm3 screened cage (BioQuip Produces, Gardena, CA) within a plastic glove box at 27°C and maintained on 30% sucrose solution. Four days after infection, mosquitoes were fed defibrinated sheep blood, using a Hemotek membrane feeding system (Discovery Workshops, Accrington, United Kingdom), as per manufacturer’s instructions. After feeding, approximately 12 blood-engorged females were removed from the cage and transferred into 48-mL individual polystyrene snap-cap plastic containers (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) with fine nylon netting on top and a moistened strip of paper toweling inside for oviposition. Cotton balls saturated with 30% sucrose solution were placed on the top of each vial. Four or 5 days later when eggs appeared on the moist toweling, the female parent was removed and frozen at −80°C for subsequent testing.

Female mosquitoes from the persistently infected Galveston Ae. aegypti colony were not inoculated with virus, but were simply fed on defibrinated sheep blood. After feeding, 12 engorged females were confined individually to plastic oviposition containers, as described earlier. When eggs appeared on the paper strip, the female was removed from the vial and frozen for subsequent testing. Egg papers were allowed to dry and were held at 27°C until the parent had been tested for CFAV infection.

Work with the Galveston and Bangkok colonies was done 2 months apart to avoid potential cross-contamination.

Rearing of F1 and F2 generation mosquitoes.

After the Galveston and Bangkok parent females had oviposited and have been tested for CFAV infection, egg papers from selected females positive for reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) were hatched in deoxygenated water. Offspring from each female parent were reared in separate larval pans at 27°C. Pupae from each family were removed and placed in a 50-mL beaker with water, which was confined within a separate 473-mL cylindrical cardboard carton covered with fine mesh.

When the F1 generation adults emerged, within 24 hours and before mating occurred, 10 or 20 males and females from each family were collected for virus assay. The remaining F1 males and females in the family were left in the cage for 5–7 days to allow mating and subsequent blood feeding. After feeding, 12 engorged F1 females were again confined individually in oviposition containers to obtain eggs of the F2 generation; then the rearing and testing process described earlier was repeated. In this manner, the offspring from two consecutive generations of the naturally infected Galveston colony and two generations of the experimentally infected Bangkok colony mosquitoes were tested, and the CFAV filial infection rates were compared.

Virus assay of mosquitoes.

Mosquitoes (parent as well as F1 and F2 adults) were thawed and placed individually into 1.5-mL Eppendorf tubes containing 600 uL of phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, with 10% fetal bovine serum. Subsequently, each insect was homogenized with a 3-mm steel ball, using a TissueLyser (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Ambien; Fisher Scientific) and RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

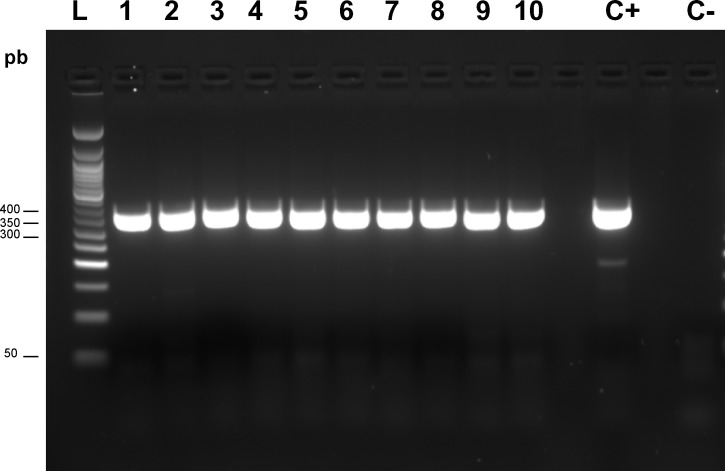

The detection of CFAV in extracted RNA from the insects was assessed by RT-PCR assay, using CFAV-specific primers designed to amplify a segment of the E gene encoded by the viral RNA. The forward and reverse primers used for CFAV were 5′AATGAGACCTGTTCGCTTAG-3′ and 5′CGTTTGTCAATCAAGGCAG-3′, respectively. Amplification was performed with each oligonucleotide primer at a final concentration of 0.5 μM with 1.0 U of avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) reverse transcriptase (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), which contained 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 0.2 mM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates in a final reaction volume of 50 μL. Thermocycling conditions for the first round of amplification were 50°C for 30 seconds and 94°C for 4 minutes, followed by 38 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 30 seconds), annealing (55°C, 30 seconds), and extension (68°C, 1 minute), and a final extension at 72°C for 7 minutes. The amplification product was visualized in a 2% agarose-1× TAE (tris-acetate-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) gel by ethidium bromide staining and UV transillumination. The expected size for amplification (PCR product) was of ∼340 bp (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Molecular detection of cell fusing agent virus partial sequences of E gene for envelope protein in Aedes aegypti from Galveston colony (L: 50 pb DNA ladder; C+: positive control; C−: negative control); lanes 1–4: female; 5–10: male F2 offspring from parents.

RESULTS

Galveston colony.

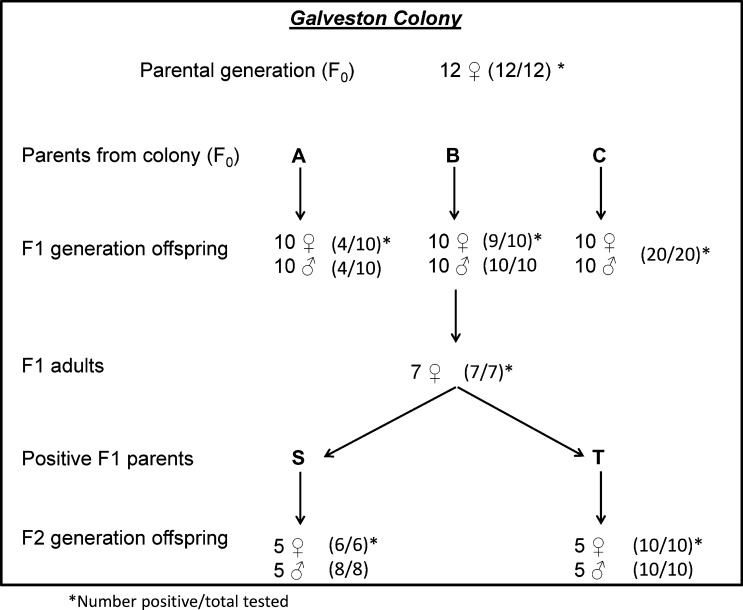

Figure 2 shows the CFAV filial infection rates among Ae. aegypti taken from the persistently infected Galveston colony. Initially, 12 females from the colony (parental or F0 generation) were blood fed, confined for oviposition, and their eggs were collected. When tested after oviposition, 12 of the 12 F0 females (100%) were RT-PCR positive for CFAV. The F1 generation eggs from three of these CFAV-positive female parents (designated A, B, and C) were hatched and 10 male and 10 female offspring of each parent were tested. F1 filial infection rates for the parents were parent A, 8/20 (40%); parent B, 19/20 (95%); and parent C, 20/20 (100%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diagram showing selection method and cell fusing agent virus infection rates in three generations of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes from the naturally infected Galveston colony.

Seven additional F1 female offspring from F0 parent B were blood fed, confined, and their eggs (F2 generation) were collected. Eggs from two of the seven RT-PCR positive F1 parent females (designated S and T) were hatched, and a sample of their F2 generation adult offspring was tested for CFAV. A total of 24 F2 offspring from F1 parents S and T, were tested; and all 24 of their F2 offspring were CFAV-positive (Figure 2). These results confirmed that CFAV was maintained by vertical transmission in the Galveston Ae. aegypti colony.

Bangkok colony.

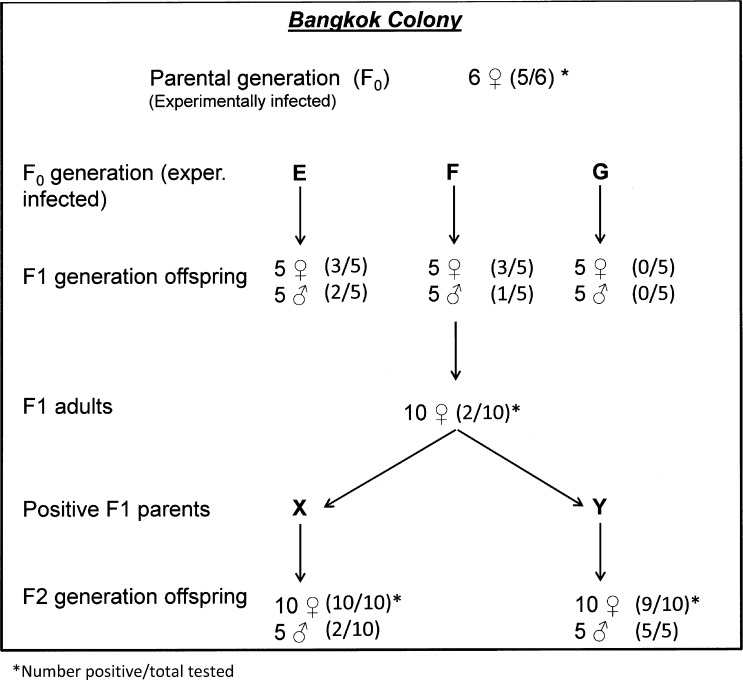

Four days after inoculation, F0 female mosquitoes from the CFAV-free Bangkok colony were blood fed and confined individually in containers for oviposition. Six of these F0 generation parents were subsequently tested for CFAV and five of the six were positive. Eggs from three of the infected F0 parents (designated parents E, F, and G) were hatched and 10 of each of their F1 offspring were tested for CFAV. The filial infection rates in their F1 progeny were parent E, 5/10 or 50%; parent F, 4/10 or 40%; and parent G, 0/10 or none infected (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Diagram showing selection method and cell fusing agent virus infection rates in three generations of Aedes aegypti from the experimentally infected Bangkok colony.

Accordingly, the remaining F1 adult female offspring of parent F were blood fed and confirmed for oviposition. After eggs were laid, 10 of these F1 females were tested for CFAV infection, but only two of the 10 F1 females (20%), designated parents X and Y, were infected. The eggs from F1 parents X and Y were hatched, reared to adults, and 35 or their F2 offspring were tested. Twelve of 20 F2 offspring (60%) from parent X were positive for CFAV; and 14 of 15 offspring (93.3%) from parent Y were infected. At this point the experiment was terminated.

DISCUSSION

The original objectives of this project were 2-fold: 1) to determine the efficiency of vertical transmission of CFAV in a naturally infected colony of Ae. aegypti (Galveston strain) and 2) to test the feasibility of introducing CFAV into another Ae. aegypti colony (Bangkok strain) that was free of the virus. Recent reports25–29 indicate that mosquitoes and mosquito cell cultures infected with some ISFVs are refractory to superinfection with a related flavivirus pathogen. It has been suggested that if one could introduce such an ISFV into a mosquito vector population, it might be possible to alter the insects’ vector competence and thus reduce transmission of specific flavivirus pathogens.13,27–29 Thus answers to the two questions (objectives) posed earlier are important in evaluating the feasibility of such an arbovirus control strategy.

The level of vertical transmission of CFAV in the naturally infected Galveston Ae. aegypti colony was high as shown in Figure 2. All (12/12) of the F0 parent females from the colony were infected. The overall CFAV filial infection rate among 60 F1 offspring from three of these parents (A, B, and C, respectively) was 78.3%. In the F2 generation, the CFAV filial rate was 100% (20/20). These results are similar to those reported by Saiyasombat and others22 with a colony of Cx. pipiens mosquitoes naturally infected with CxFV. The CxFV filial infection rate among F1 generation progeny of naturally infected, wild caught Cx. pipiens was 97.4%.22 These very high filial infection rates indicate that CFAV, CxFV, and possibly other ISFVs are maintained in their mosquito hosts by vertical transmission. This heritable transmission model (or stabilized infection) has also been demonstrated with Sigma virus (Rhabdoviridae) in Drosophila melanogaster and for La Crosse with (Bunyaviridae) in Aedes triseriatus.20

Our second objective, namely to test the feasibility of introducing CFAV into an Ae. aegypti colony (Bangkok) that was free of the virus, was successful; but F1 filial infection rates were relatively low and some selection was needed to obtain higher CFAV filial infection rates. In the F1 generation progeny of the experimentally infected (inoculated) Bangkok F0 generation females, the filial infection rate was 30% (12/40) (Figure 3). In contrast, the CFAV filial infection rate in F2 progeny from two CFAV-positive F1 females was 90% (27/30), suggesting that with further selection, one could obtain females with a “stabilized infection,” as observed in the Galveston colony.

The lower CFAV filial infection rate (30.0%) in the F1 generation progeny of the experimentally infected (inoculated) Ae. aegypti females from the Bangkok colony was comparable to other results reported by Saiyasombat and others22 in their experiments with CxFV in Cx. pipiens. The latter studies also found much lower CxFV filial transmission rates in F1 offspring of needle-infected Cx. pipiens, than in the naturally infected mosquitoes.22 However, only the F1 generation progeny were tested in this study, and no attempt was made to select for higher rates. So it may be feasible to develop mosquito colonies (lines) that are persistently infected with ISFVs.

The availability of ISFV-infected mosquito lines would allow in-depth studies of the effect of ISFV infection on the vector competence of mosquitoes for specific flavivirus pathogens. There has been considerable speculation that ISFVs can alter a mosquito’s vector competence for certain mosquito-borne flavivirus pathogens, due to heterologous interference or by altering the insect’s basal innate immunity.13,24–29 However, to date most of the experimental studies to test this hypothesis have been done in vitro, using the C6/36 mosquito cell line. But the C6/36 cell line has a dysfunctional antiviral RNA interference response and obviously does not have the full innate immune response of a live insect.30–32 The availability of ISFV-infected mosquito lines would also permit more realistic proof-of-concept studies of whether ISFVs could be used for control of certain mosquito-borne flavivirus pathogens.

Another important consideration in evaluating the feasibility of an ISFV control strategy is the mosquito host range of a candidate ISFV. Susceptibility of a mosquito to ISFV infection does not necessarily mean that the virus will be vertically transmitted in the insect.20 But vertical transmission is essential, if the candidate ISFV is going to persist in the target mosquito population. Thus CxFV would not qualify as a candidate control agent for Dengue virus 1-4 or Zika virus, since it is probably not vertically transmitted in their Aedes vectors. Likewise, CFAV could not be used as a control agent for West Nile virus (WNV), since it is unlikely to be vertically transmitted in the Culex vectors of WNV. The ability of an ISFV to be vertically transmitted and its filial infection rate can only be determined by in vivo studies in the targeted vector species. The concept of using ISFVs to alter the vector competence of mosquitoes for selected flavivirus pathogens is valid and has potential, but much more information is needed before its feasibility can be determined.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stollar V, Thomas VL, 1975. An agent in the Aedes aegypti cell line (Peleg) which causes fusion of Aedes albopictus (Singh) cells. Virology 47: 122–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peleg J, 1969. Inapparent persistent virus infection in continuously grown Aedes aegypti mosquito cells. J Gen Virol 5: 463–471. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh KRP, 1967. Cell cultures derived from larvae of Aedes albopictus (Skusex) and Aedes aegypti (L.). Curr Sci 36: 506–508. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Igarashi A, Harrap KA, Casals J, Stollar V, 1976. Morphological, biochemical, and serological studies on a viral agent (CFA) which replicates in and causes fusion of Aedes albopictus (Singh) cells. Virology 74: 174–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cammisa-Parks H, Cisar LA, Kane A, Stollar V, 1976. The complete nucleotide sequence of cell fusing agent (CFA): homology between the nonstructural proteins encoded by CFA and the nonstructural proteins encoded by arthropod-borne flaviviruses. Virology 189: 511–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook S, Bennett SN, Holmes EC, Chesse RD, Moureau G, de Lamballerie X, 2006. Isolation of a new strain of the flavivirus cell fusing agent virus in a natural mosquito population from Puerto Rico. J Gen Virol 87: 725–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calzolari M, Ze-Ze L, Vasquez A, Sanchez Seco MP, Amaro F, Dottori M, 2016. Insect-specific flaviviruses, a worldwide widespread group of viruses only detected in insects. Infect Genet Evol 40: 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamanaka A, Thongrungkiat S, Ramasoota P, Konishi E, 2013. Genetic and evolutionary analysis of cell-fusing agent virus based on Thai strains isolated in 2008 and 2012. Infect Genet Evol 19: 188–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoshino K, Isawa H, Tsuda Y, Sawabe K, Kobayashi M, 2009. Isolation and characterization of a new insect flavivirus from Aedes albopictus and Aedes flavopictus mosquitoes in Japan. Virology 391: 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espinoza-Gomez F, Lopez-Lemus AU, Rodriguez-Sanchez IP, Martinez-Fierro ML, Newton-Sanchez OA, Chavez-Flores E, Delgado-Enciso I, 2011. Detection of sequences from a potentially novel strain of cell fusing agent virus in Mexican Stegomyia (Aedes) aegypti mosquitoes. Arch Virol 156: 1263–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolling BG, Vasilakis N, Guzman H, Widen SG, Wood TG, Popov VL, Thangamani S, Tesh RB, 2015. Insect-specific viruses detected in laboratory mosquito colonies and their potential implications for experiments evaluating arbovirus vector competence. Am J Trop Med Hyg 92: 422–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collao X, Prado L, Gonzalez C, Vasquez A, Araki R, Henriquez T, Pena CM, 2015. Detection of flavivirus in mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) from Easter Island-Chile. Rev Chilena Infectol 32: 113–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolling BG, Weaver SC, Tesh RB, Vasilakis N, 2015. Insect-specific virus discovery: significance for the arbovirus community. Viruses 7: 4911–4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization , 1985. Arthropod-Borne and Rodent-Borne Viral Diseases. WHO Tech Report Series 719 Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Datta S, Gopalakrishnan R, Chatterjee S, Veer V, 2015. Phylogenetic characterization of a novel insect-specific flavivirus detected in a Culex pool, collected from Assam, India. Intervirology 58: 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Misencik MJ, Grubaugh ND, Andreadis TG, Ebel GD, Armstrong PM, 2016. Isolation of a novel insect-specific Flavivirus from Culiseta melanura in the northeastern United States. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 16: 181–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuwata R, Sugiyama H, Yonemitsu K, Van Dung N, Terada Y, Taniguchi M, Shimoda H, Takano A, Maeda K, 2015. Isolation of Japanese encephalitis virus and a novel insect-specific flavivirus from mosquitoes collected in a cowshed in Japan. Arch Virol 160: 2151–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan H, Zhao Q, Guo X, Sun Q, Zuo S, Wu C, Zhou H, An X, Pei G, Tong Y, Zhang J, Shi T, 2016. Complete genome sequence of Xishuangbanna flavivirus, a novel mosquito-specific flavivirus from China. Arch Virol 161: 1723–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cholleti H, Hayer J, Abilio AP, Mulandane FC, Verner-Carlsson J, Falk KI, Fafetine JM, Berg M, Blomstrom AL, 2016. Discovery of novel viruses in mosquitoes from the Zambezi Valley of Mozambique. PLoS One 11: e0162751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tesh RB, Bolling BG, Beaty BJ, 2016. Role of vertical transmission in arbovirus maintenance and evolution. Gubler DJ, Vasilakis N, eds. Arboviruses: Molecular Biology, Evolution and Control. Norfolk, United Kingdom: Calister Academic Press, 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolling BG, Eisen L, Moore CG, Blair CD, 2011. Insect-specific flaviviruses from Culex mosquitoes in Colorado, with evidence of vertical transmission. Am J Trop Med Hyg 85: 169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saiyasombat R, Bolling BG, Brault AC, Bartholomay LC, Blitvich BJ, 2011. Evidence of efficient transovarial transmission of Culex flavivirus by Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol 48: 1031–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanlandingham DL, McGee CE, Klinger KA, Vessey N, Fredregillo C, Higgs S, 2007. Short report: relative susceptibilities of South Texas mosquitoes to infection with West Nile virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg 77: 925–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgs S, 2005. Care, maintenance, and experimental infection of mosquitoes. Marquardt WC, ed. Biology of Disease Vectors, 2nd edition Burlington, MA: Elsevier, 733–739. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bolling BC, Olea-Papelka FJ, Eisen L, Moore CG, Blair CD, 2012. Transmission dynamics of an insect-specific flavivirus in a naturally infected Culex pipiens laboratory colony and effects of co-infection on vector competence for West Nile virus. Virology 427: 90–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hobson-Peters J, Yam AWY, Lu JWF, Setoh YX, May FJ, Kurucz N, Walsh S, Prow NA, Davis SS, Weir R, Melville L, Hunt N, Webb RI, Blitvich BJ, Whelan P, Hall RA, 2013. A new insect-specific flavivirus from northern Australia suppresses replication of West Nile virus and Murray Valley encephalitis virus in co-infected mosquito cells. PLoS One 8: e56534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenney JL, Solberg OD, Langevin SA, Brault AC, 2014. Characterization of a novel insect-specific flavivirus from Brazil: potential for inhibition of infection of arthropod cells with medically important flaviviruses. J Gen Virol 95: 2796–2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall-Mendelin S, McLean BJ, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Hobson-Peters J, Hall RA, 2016. The insect-specific Palm Creek virus modulates West Nile virus infection in and transmission by Australian mosquitoes. Parasit Vectors 9: 414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goenaga S, Kenney JL, Duggal NK, Delorey M, Ebel GD, Zhang B, Levis SC, Enria DA, Brault AC, 2015. Potential for co-infection of a mosquito-specific flavivirus, Nhumirim virus, to block West Nile virus transmission in mosquitoes. Viruses 7: 5801–5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott JC, Brackney DE, Campbell CL, Bondu-Hawkins V, Hjelle B, Ebel GD, Olson KE, Blair CD, 2010. Comparison of dengue virus type 2-specific small RNAs from RNA interference-competent and -nocompetent mosquito cells. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4: e848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brackney DE, Scott JC, Sagawa F, Woodward JE, Miller NA, Schilkey FD, Mudge J, Wilusz J, Olson KE, Blair CD, Ebel GD, 2010. C6/36 Aedes albopictus cells have a dysfunctional antiviral RNA interference response. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4: e856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jupatanakul N, Dimopoulos G, 2016. Molecular interactions between arboviruses and insect vectors: insects’ immune responses to virus infection. Gubler DJ, Vasilakis N, eds. Arboviruses: Molecular Biology, Evolution and Control. Norwalk, United Kingdom: Calister Academic Press, 107–118. [Google Scholar]