Abstract

Endometriosis is a disease distinguished by the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity with intralesional recurrent bleeding and resulting fibrosis. The most common locations for endometriosis are the ovaries, pelvic peritoneum, uterosacral ligaments, and torus uterinus. Typical symptoms are secondary dysmenorrhea and cyclic or chronic pelvic pain. Unusual sites of endometriosis may be associated with specific symptoms depending on the localization. Atypical pelvic endometriosis localizations can occur in the cervix, vagina, round ligaments, ureter, and nerves. Moreover, rare extrapelvic endometriosis implants can be localized in the upper abdomen, subphrenic fold, or in the abdominal wall. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) represents a problem-solving tool among other imaging modalities. MRI is an advantageous technique, because of its multiplanarity, high contrast resolution, and lack of ionizing radiation. Our purpose is to remind the radiologists the possibility of atypical pelvic and extrapelvic endometriosis localizations and to illustrate the specific MRI findings. Endometriotic tissue with hemorrhagic content can be distinguished from adherences and fibrosis on MRI imaging. Radiologists should keep in mind these atypical localizations in patients with suspected endometriosis, in order to achieve the diagnosis and to help the clinicians in planning a correct and complete treatment strategy.

Endometriosis is a systemic disease that affects about 10% to 20% of women during their reproductive age, characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity (1). Endometriosis lesions are characterized by intralesional recurrent bleeding during menses, because of the hormonal responsiveness of ectopic endometrial tissue, with resulting fibrosis. Typical symptoms are cyclic or chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and pain during defecation or urinating. Unusual endometriosis localizations may be associated with more specific symptoms depending on the site of the localization. According to Siegelmen et al. (2) there are three forms of pelvic endometriosis: (a) superficial peritoneal lesions; (b) ovarian endometrioma; (c) deep (or solid infiltrating) endometriosis (DIE), which is histologically identified as a lesion that extends more than 5 mm into the subperitoneal space and/or affects the wall of organs in the pelvis and ligaments. In superficial endometriosis, superficial plaques are disseminated across the peritoneum, adnexa and ligaments of the uterus; these noninvasive implants are well recognized at laparoscopy and not often detectable with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Laparoscopy is the standard of reference for the diagnosis of endometriosis but nodules covered by adhesions and subperitoneal disease are difficult to study. Pouch of Douglas, uterosacral ligaments, torus uterinus, and bowel are the most frequent sites of deep pelvic endometriosis localization. Atypical pelvic localizations of endometriosis can occur at level of the cervix, vagina, round ligaments, ureter, and nerves. Rare extrapelvic endometriosis implants can also be localized in the upper abdomen, subphrenic fold, or subcutaneous fat tissue of the abdominal wall. The focus of this review is to describe atypical pelvic and abdominal localizations of endometriosis that should be known by radiologists in order to correctly identify and characterize these lesions on MRI. Moreover, we describe the MRI appearance of the implants at specific sites and review the literature with special attention to imaging reports and description.

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis of endometriosis is probably multifactorial, and several theories have been suggested: (a) The metastatic theory, supported by the thesis of retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes, holds that endometrial cells migrate in the abdominal cavity following the clockwise peritoneal circulation, causing ectopic implantations on the serosal surface and remaining viable (3–6). This theory is the most widely accepted explanation for diaphragmatic and pleural localizations of endometriosis. (b) Coelomic-metaplastic theory, supported by the knowledge that endometrial, pleural, and peritoneal cells stem from coelomic wall-epithelium, states that endometriosis develops from metaplastic differentiation of these cells into functioning endometrial cells following pathologic stimuli (4–6). (c) Induction theory is a combination of the first two theories and states that endometrium could release factors that influence undifferentiated mesenchyme to form endometriosis accumulation (3). (d) Lymphatic or hematogenous microembolization theory is supported by histopathologic evidence of endovascular endometrial epithelium, and uterine surgical procedures are considered as risk factors (6). (e) A recent theory is based on the stimulation of local immune factors (6). Moreover, spread to distant site may occur iatrogenically during surgery or needle biopsy (5).

MRI: technical requirements and evaluation

MRI study is an advantageous technique because of absence of ionizing radiation, multiplanar ability, and high contrast resolution with high sensitivity for detection of hemorrhagic lesions.

Endometriosis is a multifocal and systemic disease and MRI allows complete evaluation of abdomen and pelvis within a single study, identifying and mapping all endometriosis lesions. These characteristics have made MRI the imaging of choice for correct disease detection and evaluation. The MRI protocol is presented in the Table. The MRI signal of endometriotic lesions could be various and is influenced by the age of hemoglobin degradation products. In the past, some authors have suggested that MRI should be performed between the 8th and 12th day from the menstruation because the blood degradation products allow the identification of active endometriosis as very bright lesions on T1-weighted images (7). However, the recent European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) guidelines for MRI of pelvic endometriosis suggest no recommendation for timing of MRI in relation to the menstrual cycle in the evaluation of deep pelvic endometriosis. (8). Superficial endometriotic lesions and endometrioma appear hyperintense on T1-weighted images when recent, or hypointense on T1-weighted images and heterogeneously hyperintense on T2-weighted images when old; however, superficial implants are rarely seen on MRI. Use of fat saturation is recommended. Chemical frequency-selective fat saturation suppresses the high signal intensity of fat tissue, enhancing differences among non-fat T1-weighted hyperintense structures and magnifying small hemorrhagic lesions of endometriosis (2). Deep pelvic endometriosis appears as solid and fibrous lesions, characterized by low signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images. These lesions are infiltrative and usually surrounded by fibrous tissue and smooth muscle, both showing low signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images (2, 9). High-resolution T2-weighted images are used to evaluate these lesions, particularly those involving ligaments and subperitoneal space. In later stage, endometriosis is frequently complicated by formation of adhesions, which is usually seen as spiculated, low-to-intermediate signal intensity bands on T1- and T2-weighted images. Adhesions may obscure organ interfaces causing atypical radiologic findings such as obliteration of peritoneal space, loculated fluid collection, and attraction and distortion of adjacent organs.

Table.

MRI protocol

| Sequences | TE (ms) | NEX | TR (ms) | N° of sections | Receiver bandwidth (kHz) | Echo train length | FOV (mm) | Section thickness (mm) | Section spacing (mm) | Matrix size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAG T2 | FRFSE- XL | 85 | 2 | 4500 | 26 | 41.67 | 15 | 24 | 4 | 0.4 | 384×256 |

| AX T1 | FSE- XL | 16 | 2 | 470 | 30 | 31.25 | 3 | 24 | 4 | 0.5 | 448×288 |

| AX T2 | FRFSE- XL | 85 | 2 | 4500 | 30 | 31.25 | 26 | 24 | 4 | 0,5 | 384×256 |

| AX T1 Fat Sat | GRE | 16 | 2 | 470 | 30 | 31.25 | 3 | 24 | 4 | 0.5 | 448×288 |

| COR T2 | FRFSE | 85 | 4 | 4500 | 16 | 41.67 | 26 | 24 | 4 | 0.5 | 384×256 |

| SAG T1 Fat Sat | GRE | 16 | 2 | 470 | 30 | 31.25 | 3 | 24 | 4 | 0.4 | 384×256 |

| AX DWI | EPI B 800 | Min | 6 | 5425 | 30 | 28 | 4 | 0.5 | 128×128 | ||

| AX T2 upper abdomen | FRFSE- XL | 84 | 1 | 1850 | 48 | 41.67 | 17 | 46 | 5 | 1 | 256×256 |

| AX LAVA (30′ 60′ 90′) | 3D T1 Prep | Min | 1 | Default | / | 62 | 30 | 4 | −2 | 320×192 | |

| Optional sequences | |||||||||||

| Abdomen | |||||||||||

| AX T1 Fat Sat | FSPGR | Min | 1 | 150 | 16 | 41.67 | 42 | 6 | 1 | 256×256 | |

| COR T1 Fat Sat | FSPGR | Min | 1 | 150 | 16 | 41.67 | 46 | 4 | 0 | 256×256 | |

| SAG T1 Fat Sat | FSPGR | Min | 1 | 150 | 16 | 41.67 | 46 | 6 | 1 | 256×256 | |

| Nerve | |||||||||||

| COR T2 | FRFSE | 90 | 2 | 4858 | 31 | 20.83 | 21 | 43 | 5 | 0.7 | 512×512 |

| COR T1 | FSE | Min | 2 | 813 | 30 | 27.78 | 5 | 42 | 5 | 0.4 | 512×512 |

| AX T1 | FSE | Min | 2 | 585 | 48 | 35.71 | 5 | 44 | 5 | 1 | 512×512 |

| AX T2 | FRFSE | 92 | 2 | 4378 | 48 | 25 | 22 | 44 | 5 | 1 | 512×512 |

| Ureters | |||||||||||

| UroRM | Radial HR | 1200 | / | Min | 16–19 | / | / | 46 | 60 | / | 512×384 |

TE, echo time; NEX, number of excitations; TR, repetition time; FOV, field of view; SAG, sagittal; FRFSE-XL, fast-recovery fast spin-echo accelerated; AX, axial; FSE-XL, fast spin-echo accelerated; GRE, gradient echo; Fat Sat, fat-saturated; COR, coronal; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; LAVA, liver acquisition with volume acceleration; FSPGR, fast spoiled gradient recalled; UroRM, magnetic resonance urography; HR, high resolution.

Axial, coronal, and sagittal planes are recommended; oblique planes oriented on the involved organs could also be helpful.

The usefulness of intravenous gadolinium injection to characterize endometriosis is still the subject of discussion because it does not add substantial information. However, it remains mandatory when malignant transformation of endometrioma is suspected (10).

Diffusion-weighted imaging sequences and apparent diffusion coefficient map are usually added to MRI pelvic studies, but their role in diagnosis of endometriosis is still under investigation (2, 11, 12).

New MRI sequences have been suggested but are still limited to research trials and are used for specific clinical requests, such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) to assess integrity of fiber tracts in pelvic endometriosis or susceptibility-weighted imaging to improve detection of blood products (10–13).

Vaginal opacification with sonographic gel is considered as an option in the evaluation of deep pelvic endometriosis (8).

Pelvic endometriosis

Cervix

Epidemiology and clinical characteristics

Cervical endometriosis is a rare and usually incidental microscopic finding (0.1%–2.4%) (11). Pathogenesis is probably related to a history of cervical trauma (such as curettage, biopsy, and vaginal delivery) with implantation of endometrial fragments. In patients who have not undergone prior invasive procedures, it may result from Müllerian rests in cervical stroma (5, 14). Cervical endometriosis is usually asymptomatic, but it can rarely present with irregular or abnormal vaginal bleeding (5, 15).

MRI features

The normal cervix demonstrates a trilaminar aspect on T2-weighted images: high signal (endocervical glands) surrounded by low signal (cervical stroma) and an external rim of intermediate signal intensity (smooth muscle). Cervical endometriosis could appear as a nodular, cystic, or polypoid mass (14). As reported, cervical endometriosis may show a cystic hemorrhagic component as area of hyperintensity on both T1- and fat-suppressed T1-weighted images surrounded by the T2-weighted hypointense cervical stroma (14), or it could have different presentation as well as simple cystic aspect (Fig. 1). T2-weighted axial and coronal sequences assessed on the axis of the cervix could improve the diagnosis.

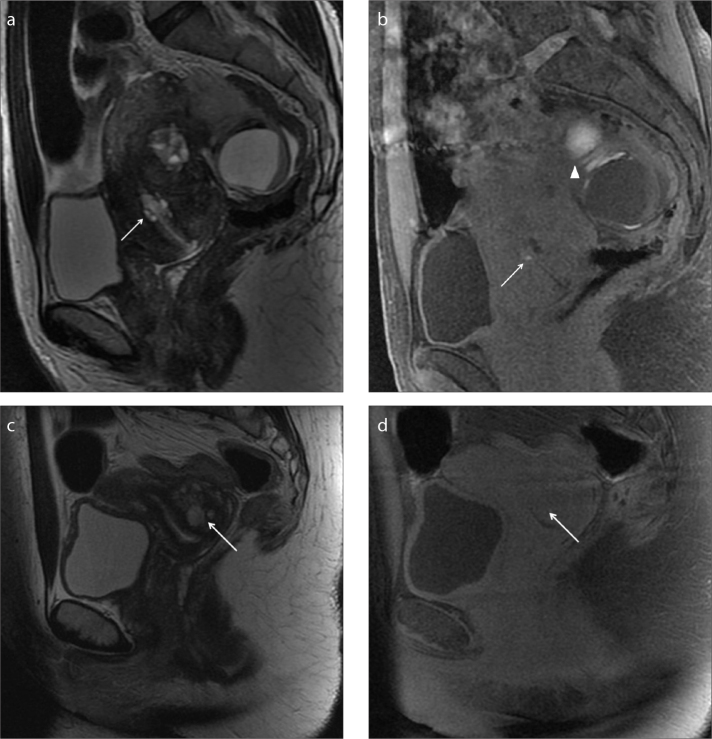

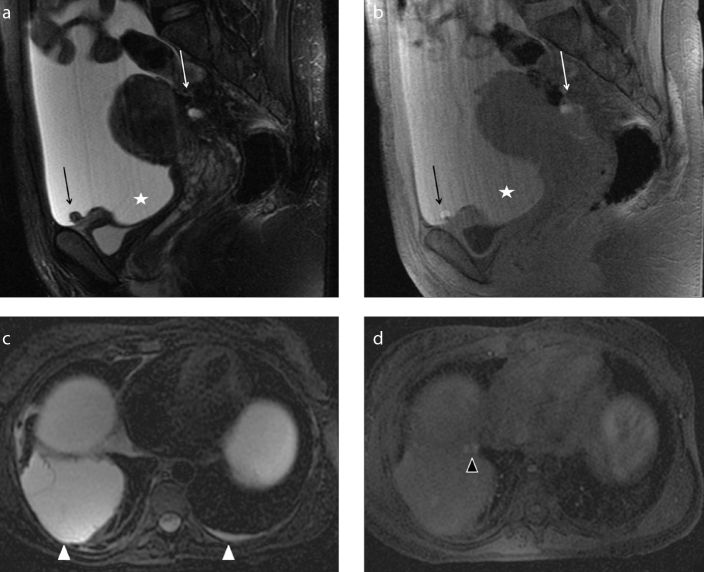

Figure 1. a–d.

A 45-year-old woman complaining of cyclic abdominal pain and spotting (a, b) and a second case of a 40-year-old woman complaining of spotting (c, d). Sagittal T2-weighted image (a) and T1-weighted image with fat-suppression (b) show a small bright area in the cervix, within the cervical stroma, hyperintense in both sequences as hemorrhagic content (white arrow). The patient has concomitant multiple signs of endometriosis on the left ovary (b, white arrowhead). In the second case, the sagittal T2-weighted image (c) and T1-weighted image with fat-suppression (d) show a focal area in the cervical stroma that appears hyperintense on T2-weighted images and isointense on T1-weighted images as fluid continent (c, d, white arrow). In spite of the MRI appearance, cervical biopsy reveals endometriotic hyperplasia.

The first line management on symptomatic patients is conservative medical treatment. In nonresponsive patients surgical lesion resection is indicated.

Vagina

Epidemiology and clinical characteristics

Vaginal endometriosis is a rare condition (involving 5% of the cases) characterized by a lesion usually located in the posterior fornix or in the upper part of posterior vagina (16). Main symptoms are dyspareunia and painful defecation during menses (6). Transvaginal ultrasound has poor sensitivity (44%) in detection of vaginal nodules, related to the configuration of the probe oriented toward the vaginal fornix (17).

MRI features

The submucosal and the muscularis layer are low signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images. Surrounding external layer contains fat and a venous plexus that has slow flow, demonstrating high signal on T2-weighted sequences. On MRI, vaginal mucosa is not well distinguished.

Vaginal endometriotic localization is observed as hypointense parietal posterior thickening on T2-weighted images, or as a mural nodule with variable intensity on T1-weighted images related to the presence of hemorrhagic foci (Fig. 2) (18). Obliteration of the retrouterine recess could be a sign of posterior vaginal involvement. In case of vaginal wall involvement, MRI could guide the surgery since removal of the upper part of the vaginal wall is still mandatory for eradication (7).

Figure 2. a–c.

A 35-year-old woman with history of painful defecation, in particular during menses. Axial T2-weighted (a), sagittal T1-weighted with fat-suppression (b), and sagittal T2-weighted (c) images identify a small nodule in the posterior vaginal fornix hypointense on T2-weighted images and hyperintense on T1-weighted images due to hemorrhagic component (white arrow). Note the coexisting left intraligamentous uterine pedunculated fibroma (a, black arrow). The patient has multiple concomitant bilateral small endometriomas.

Round ligament

Epidemiology and clinical characteristics

Incidence of endometriosis of the round ligaments of the uterus (RLUs) is between 0.3% and 14% (1, 19, 20). RLUs have an intrapelvic and an extrapelvic portion where the extrapelvic one is the distal part of the ligament in the canal of Nuck (1). Patients with endometriosis involvement of the extrapelvic portion of the RLUs at the level of the canal of Nuck usually refer a painful, palpable inguinal mass, with or without menstrual variation. Symptoms of the endometriosis of the intrapelvic portion of the RLUs are nonspecific, usually referred as pain localized in the lower abdomen (19).

MRI features

Round ligaments are bilateral thin structures consisting of muscular tissue. They arise from the uterine horns, course laterally from the uterus through the broad ligament, cross internally and ahead, then externally to iliac vessels, and run along the pelvic sidewall leaving the abdomen via the internal ring. They pass through the inguinal canal and terminate in the labia majora. They normally show fibrous signal on both T1- and T2-weighted sequences. Affected ligament appears thickened, usually more than 1 cm, shortened, and irregular, with nodular aspect on T2-weighted sequences (1, 19). The signal could be various, depending on the presence of stromal tissue, glandular elements, hemorrhage, inflammatory reaction, or fibrous tissue. Pure fibrous localizations show low signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted sequences whereas hemorrhagic foci show high signal intensity on T1-weighted and/or fat-suppressed T1-weighted sequences (Figs. 3, 4). A mixture of these two components, namely, fibrous tissue with low signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging and small hemorrhagic foci depicted as hyperintense signal on T1-weighted imaging are the most frequent lesions (1, 19, 20). The detection of free fluid around the RLUs on “antideclive position” might be an indirect sign of endometriosis of the intrapelvic portion of the RLUs (21).

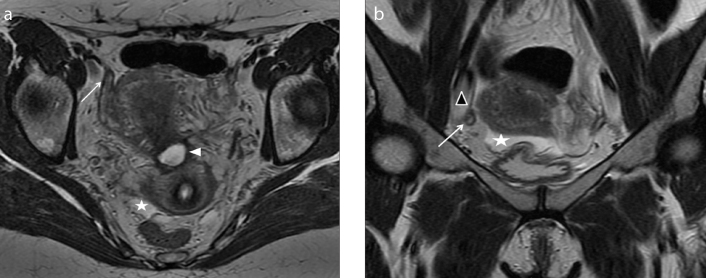

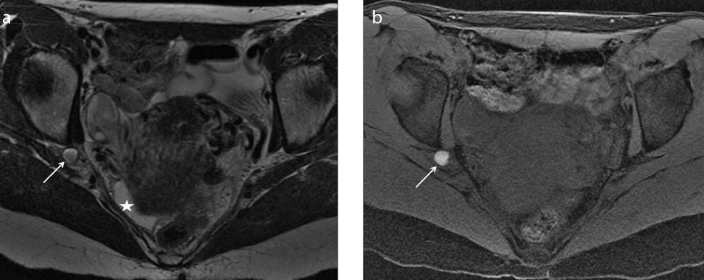

Figure 3. a, b.

A 36-year-old patient referred with chronic pelvic pain and suspicion of pelvic endometriosis. Axial T2-weighted images (a) reveal morphologic abnormalities of intrapelvic portion of the right round ligament (white arrow) that appear thickened and shortened. Coronal T2-weighted image (b) better identifies the thickness of the distal intrapelvic portion of the right round ligament (white arrow), where it courses medial to adjacent external iliac vessels (black arrowhead) and before the inguinal canal. Anterior and posterior free pelvic fluid is also seen (white star). Note the isthmocele within the anterior wall of the uterus (a, white arrowhead). MRI examination leads the suspicion of deep endometriosis with right round ligament involvement.

Figure 4. a, b.

A 28-year-old woman complaining of cyclic abdominal pain and painful tumefaction of the right groin, who underwent medical therapy for pelvic pain. Axial T2-weighted image (a) shows a hypointense area with spiculated margins in the right inguinal region (white arrow). The mass is strictly adjacent to the extrapelvic portion of the right round ligament of the uterus, where it passes through the inguinal canal. Axial T1-weighted image with fat-suppression (b) shows the isointense signal of the lesion (white arrow) with very small and mild hyperintense foci in the caudal portion, related to hemorrhagic components (white arrowhead). The lesion is suspicious for extrapelvic localization of deep endometriosis of the round ligament at the level of the canal of Nuck.

Urinary tract

The urinary tract is affected by endometriosis in 0.2%–2.5% of all cases (1). Endometriotic lesions in urinary tract are frequently combined with other simultaneous localizations in the pelvis (in 50%–75% of cases) (3).

Bladder

Epidemiology and clinical characteristics

Bladder is the most involved organ in the urinary tract, while endometriotic implants can rarely affect distal ureters, kidneys, and urethra (22). The peritoneum covers the bladder dome with creation of an anterior fold with the pelvic wall called prevesical recess, and a posterior fold with the uterus known as the vesicouterine pouch or anterior cul-de-sac. The most common bladder involvement by endometriotic implants is located on the serosal surface of the vesicouterine pouch (extrinsic involvement); however, implants can invade the muscular layer and protrude into bladder lumen as mural masses (intrinsic involvement) (3, 5). Extrinsic localizations are more common, often asymptomatic and typically associated with involvement of vesicovaginal recess, the anterior uterine peritoneum, or the uterine insertion of round ligaments (3). Pathogenesis is still uncertain, and the most reasonable hypothesis is the reflux of endometrial cells through the fallopian tubes to the vesicouterine pouch (23). Moreover, the bladder involvement can be related to iatrogenic endometrial implantation by previous pelvic surgery. Symptoms are suprapubic pressure, dysuria, and urgency or hematuria (22). Ultrasound examination is useful in the detection of bladder involvement, in particular with transvaginal study showing hypoechogenic nodules in vesicouterine pouch (22, 24).

MRI features

Bazot et al. (18) reported high MRI accuracy in detection of bladder endometriosis. Mild bladder distension during MRI examination is recommended to better appreciate the detrusor muscle (7). The coronal plane is crucial as it allows an optimal visualization of the vesicouterine space and the bladder dome (1). The main MRI finding is a nodular or diffuse thickening of bladder wall with irregular margins, sometimes with protrusion in the lumen, which may mimic cancer. The nodular aspect typically adheres to the uterus, showing an obtuse angle with the vesical wall and is related with anteflexion of the uterus and the elimination of the anterior cul-de-sac. The signal is inhomogeneous and replaces the normal signal of detrusor muscle; the lesion can show low signal intensity on T2-weighted images with high signal spots on T1-weighted images related to hemorrhagic foci (Fig. 5). Sometimes, mild hyperintense foci on T2-weighted images may be present, corresponding to dilated endometrial glands. Gadolinium injection does not improve the diagnosis of bladder wall endometriosis (8). Definitive differential diagnosis with neoplasm requires cystoscopy and biopsy (6).

Figure 5. a, b.

A 30-year-old woman complaining of cyclic pelvic pain and discomfort during urination. Coronal T2-weighted (a) image shows focal and irregular hypointense wall thickening of the upper aspect of the bladder wall (white arrow) that obliterates the vesicouterine fold and distorts the bladder wall. The detrusor muscle seems to be infiltrated and the lesion seems to project into the lumen (black arrow). Coronal T1-weighted images with fat-suppression (b) show hyperintense foci within the mass that can be attributed to hemorrhagic content (white arrowhead). Laparotomy confirmed endometriotic localization of the vesicouterine fold with bladder wall involvement.

Ureters

Epidemiology and clinical characteristics

Ureteral involvement is less common than bladder involvement. Similar to bladder endometriosis, extrinsic ureteral involvement is the most common form (75%–80% of the cases). Extrinsic endometrial involvement is represented by encasement of ureter by endometrial tissue spreading in outer adventitia and into surrounding connective tissue from adjacent organs (ovary, broad, and uterosacral ligaments). Moreover, fibrosis without true endometrial tissue can cause extrinsic ureteral involvement. The rare intrinsic ureteral involvement occurs when ectopic endometriosis tissue is present in the mucosal or muscular layer of ureters, from deep infiltrating periureteral lesion or, hypothetically, from lymphatic or venous metastases (1, 3). The majority of the localizations occur in the tract of the ureter within the pelvis; they are often unilateral (80% of the patients) and more common on the left side (1, 25). Clinical diagnosis is very difficult because symptoms, such as renal colic, lumbago, or hematuria, are nonspecific. Moreover, the disease may progress leading to a failure of renal function via inveterate hydronephrosis (1).

MRI features

The course of the ureters is directed posteromedially over the external iliac vessels towards the meatus on the bladder, passing via the space lateral to the cervix and uterosacral ligaments and inferior to cardinal ligaments (3). The normal nonopacified ureter can be difficult to analyze on MRI because it is a hallow structure only 4–5 mm in size, representing the limit of MRI spatial resolution. MRI may reveal direct signs of extrinsic ureteral involvement, such as a nodule strictly adjacent to the ureter, usually showing low signal intensity on T2-weighted images due to fibrosis, with high signal foci on both T2- and T1-weighted images (Fig. 6). Involvement of the ureters should be considered when there is obliteration of the fat interface between the nodule and the ureters on T2-weighted images (7). Moreover, MRI can show indirect signs such as retractile periureteral adhesions (visible as low signal intensity lines with angular deviation) or ureteral dilatation cranial to the obstruction site. Hydronephrosis can also be detected using magnetic resonance urography, acquired with both two-dimensional T2-weighted sequences and delayed contrast-enhanced three-dimensional sequences with higher spatial resolution (26). The presence and grade of ureteral involvement is clinically relevant, because it requires a different surgical approach with the presence of an urologist.

Figure 6. a, b.

A 31-year-old woman referred with pelvic pain, infertility, and US suspicion of endometrioma. Coronal T2-weighted image (a) shows mostly hyperintense large left ovarian mass (white arrowheads) with inhomogeneous component in declive position. The left ureter (a, black arrow) appears stretched and striped by fibrous tissue and adhesions adjacent to the endometrioma; adhesions and fibrous tissue are characterized by hypointense signal on both T2-weighted and T1-weighted images (a, b, white arrow). This tissue causes extrinsic stenosis of the ureter with associated hydronephrosis. Axial T1-weighted image with fat-suppression (b) reveals the hyperintense signal of the mass due to hemorrhagic component, chronic blood products and coagulum whitout hemorrhagic foci.

Sciatic nerve

Epidemiology and clinical characteristics

Pelvic nerve endometriosis implants (sacral plexus, pudendal or sciatic nerves) are very rare extraperitoneal localizations.

The symptoms are characterized by cyclic sciatica with recurrent pain along the course of the sciatic nerve simultaneous with menstruation, associated with gluteal pain and locomotor deficit (3, 27). In young women with catamenial sciatica, the suspicion of sciatic nerve endometriosis should be considered. Catamenial sciatica may be combined with signs of involvement of other pelvic nerves and other signs indicative of endometriosis. The pathogenesis of endometriotic involvement of pelvic nerve is still not well explained. The theory of defective embyogenesis and migration of endometrial tissue could explain this kind of involvement.

MRI features

Each sacral plexus is composed by L4 and L5 nerves, lumbosacral trunk, and S1–S4 sacral nerves, which go into the pelvis via the sacral foramina. The sacral plexus is placed on the piriformis muscle covered by the parietal pelvic fascia. The sciatic nerve and pudendal nerve arise from sacral plexus (28). The most frequent site of involvement is the sciatic nerve in the area of the sciatic notch (29, 30). In the appropriate clinical setting high quality MRI performed by an expert radiologist is crucial to identify and characterize the endometriosis lesion along the nerve pathways. Moreover, MRI can identify and map all other concomitant endometriosis pelvic lesions.

Sciatic nerves are mild symmetric T2 hyperintense linear structures that become hypointense to the muscle in the thigh. The nerve road is smooth and no focal variations of the internal fascicular architecture or focal enlargement should be detected (31).

Sciatic implants have been described as heterogeneous fibrous nodules adjacent to the nerve plexus containing hemorrhagic foci on T1-weighted images that support the endometriosis origin (Fig. 7) (27). The sciatic nerve involvement has been associated with the “pocket sign” related to a small peritoneal evagination often situated on the posterior part of the pelvis drawn downward the greater sciatic notch (31).

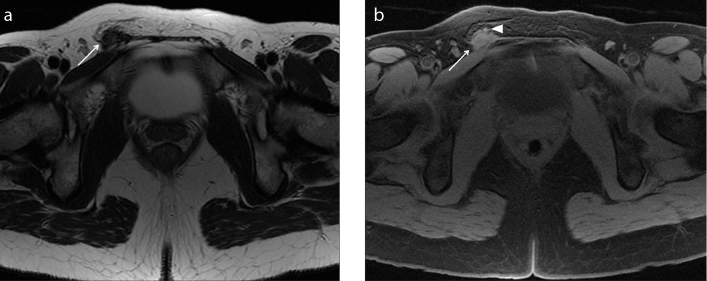

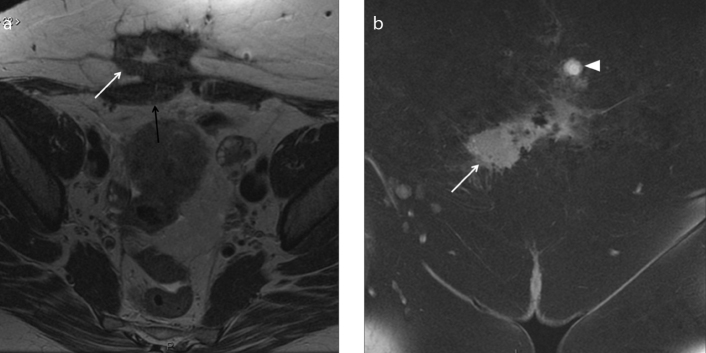

Figure 7. a, b.

A 39-year-old patient with cyclic abdominal and right sciatic pain. Axial T2-weighted (a) and T1-weighted fat-suppression (b) images show a right nodular lesion (white arrow) located in the fat tissue between the posterior wall of acetabulus and piriform muscle, in the anatomical space where sciatic nerve is typically found. The nodular lesion shows heterogeneous hyperintense signal on T2-weighted image and hyperintensity on T1-weighted image, due to hemorrhagic content, suspicious for endometriotic localization. Free pelvic fluid is also depicted (a, star). The sciatic endometriosis was surgically confirmed.

Sciatic involvement is better examined adding to standard protocol high matrix coronal and axial T2-weighted and T1-weighted sequences. DTI has recently been suggested as an additional MRI sequence to assess integrity of fiber tracts of pelvic nerve routes (13). Management of sciatic nerve endometriosis is multidisciplinary and requires experienced gynecologic surgeons, neurosurgeons, and radiologists for proper diagnosis and treatment (both medical and surgical).

Extrapelvic endometriosis

Abdominal wall

Epidemiology and clinical characteristics

Endometriosis of the abdominal wall is the most frequent extrapelvic endometriosis localization (incidence, 0.03%–2%) (1, 32). Abdominal wall endometriosis has been described in different sites, such as subcutaneous soft tissue, rectus muscles, or both, usually next to surgical scar site of hysterectomy or cesarean section or along the track for a needle for amniocentesis or trocar for laparoscopy (1, 5). The pathogenesis is presumed to be multifactorial and result from iatrogenic ectopic transplantation and local growth of endometrial cells (1, 5, 32). Rare spontaneous parietal endometriosis occurring around the umbilicus has been reported in scarless abdominal wall by presumed hematogenic or lymphogenic spread of endometriosis cells from the abdomen (1, 5, 32). Abdominal wall endometriosis is usually not associated with history of pelvic endometriosis (5, 33). The most common clinical presentation is localized constant abdominal pain and swelling. The menstrual character of the symptoms occurs in only about 25% of patients (1, 29, 33). The symptoms are frequently atypical and can manifest many weeks or years from surgery (median, 30 months) (1). The correct preoperative diagnosis is assessed in only 25%–50% of cases. Fine needle aspiration may help to obtain the diagnosis in doubtful cases; however, the possibility of spread along the course of the needle should be noted (1, 5). Surgery is the treatment of choice for superficial lesions (5).

MRI features

The integration of ultrasound and MRI is the best approach in the diagnostic workup to establish the correct diagnosis. Differential diagnosis includes abdominal wall masses, such as hernias, lipomas, sebaceous cysts hematomas, and malignant tumors (5, 33). Parietal endometriotic lesions show iso- or high signal intensity compared with the muscle on both T2- and T1-weighted sequences. The hyperintense foci on T1-weighted images with fat suppression are due to small hemorrhages (Fig. 8, 9). However, the absence of hemorrhagic foci may be caused by hormonal treatment (32). The size of the parietal lesions could vary from 5 to 200 mm (mean diameter, 40 mm) (1). T1-weighted images with fat-suppression has been reported to be the most sensitive sequence for nodules smaller than 10 mm (1). Moreover, to magnify the lesions, some MRI adaptation techniques are important, such as avoiding to position a pre-saturation band on the abdominal wall and using a cutaneous reference mark to center the study in the clinically suspicious area (1).

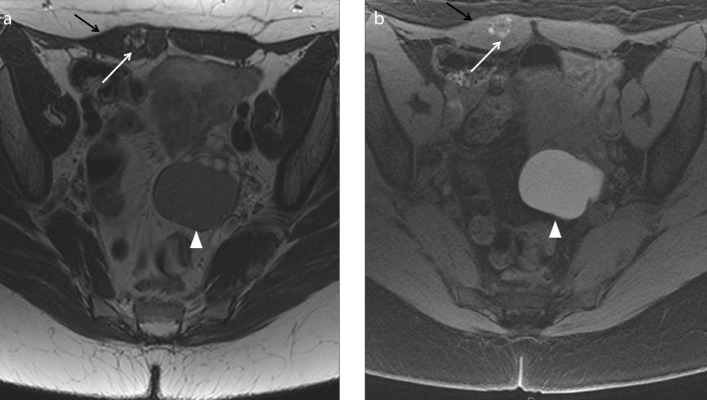

Figure 8. a, b.

A 45-year-old woman with history of previous cesarean sections suffering from localized abdominal pain at the site of a palpable parietal mass. Axial T2-weighted image (a) shows the presence of a hypointense spiculated mass in the subcutaneous soft tissue of abdominal wall (white arrow). The mass is strictly adjacent to the right rectus abdominis muscle (black arrow). The coronal T1-weighted images with fat-suppression (b) show slight hyperintense signal of the mass (white arrow) with some hyperintense areas due to hemorrhagic component; the coronal image reveals another small nodular lesion (white arrowhead) depicted cranially as hyperintense signal on T1-weighted image with fat-suppression. The lesions are due to abdominal wall deep endometriosis implants. Histopathology confirmed the endometriotic nature of the lesions.

Figure 9. a, b.

A 33-year-old woman with history of pelvic pain and previous cesarean section. Axial T2-weighted image (a) shows a small nodular intramuscular lesion (white arrow) within the right rectus abdominis muscle (black arrow) with heterogeneous and predominantly hyperintense signal. Axial T1-weighed image with fat-suppression (b) shows the hyperintense signal of the lesion due to hemorrhagic foci (white arrow). Left endometrioma is also depicted (a, b, white arrowhead). Surgery confirmed the suspicion of intramuscular endometricotic focus.

Diaphragmatic and pleural localization

Epidemiology and clinical characteristics

Diaphragmatic localization of endometriosis is described in the literature but it is still considered very rare (the largest reported series is of eight surgically treated patients) (6). Diaphragmatic endometrial implants are described underneath the diaphragm, on the peritoneal surface and upwards on thoracic cavity attached to the pleura or within the muscle. Pathogenesis is controversial. The metastatic theory, supported by the concept of retrograde menstruation, is the most agreed. Endometrial cells in the peritoneal cavity reach the right subdiaphragmatic area via the right paracolic gutter and the preferential site of implantations is peritoneal area close to the posterosuperior tendinous portion of the right diaphragm (6, 34). The left subdiaphragmatic area is less affected because phrenocolic ligament and the falciform ligament form the barrier to the coming cells and fluid. However, these lesions cannot be simply visualized with a laparoscope from an umbilical port. Redwine et al. (35) introduced a new concept in diaphragmatic endometriosis, where a sentinel small lesion of the anterior diaphragm could represent the Trojan horse, viewed by laparoscopy through an umbilical port. The most common symptoms reported in patients with diaphragmatic endometriosis localization are right-sided chest or shoulder pain associated with menses, sometimes with radiation of pain up to the neck or down the arm. Pain can be severe, sometimes described similar to a deep muscular ache, with cyclic onset that gradually becomes continuous all month long (35). This muscular pain is defined as “diaphragmatic” where it involves phrenic nerve irradiations (6). Some patients reported intense menstrual aggravation of breathing. Symptomatic diaphragmatic endometriosis is always associated with symptomatic pelvic endometriosis (35). Congenital or acquired diaphragmatic defects lead to transdiaphragmatic passage of endometrial tissue (36, 37). Endometrial cells can cross the thickness of diaphragmatic muscle followed by cyclical necrosis and may form canals in the muscle that permit other implants enter into the pleural space and colonize other parts of the chest (6, 35). When pleural localization occurs, patients may refer symptoms of the pleural thoracic endometriosis syndrome, including catamenial pneumothorax, non-catamenial endometriosis related pneumothorax and catamenial hemothorax (6).

MRI features

In these patients computed tomography scan is usually performed at first, but MRI performed during menses could confirm the hemorrhagic nature of implants. Morphologic sequences acquired during breath-holds are recommended, including fast spin-echo T2-weighted with or without fat suppression, unenhanced T1-weighted and three-dimensional gradient-echo T1-weighted sequences with fat suppression, all performed in the axial and coronal planes. Acquisition can be completed by a right-sided sagittal sequence. Gadolinium injection is not considered mandatory. The size and appearance of the endometriotic lesions can vary with the age of hemorrhage and the phase of the menstrual cycle (6). Typical diaphragmatic endometriotic implants are located on the right posterosuperior diaphragmatic area and appear hyperintense in all sequences, better depicted on T1-weighted sequences with fat saturation. However, because of the presence of lung and air closer to diaphragm, these lesions must be distinguished from susceptibility artifacts. Otherwise, pleural localizations can be small with cystic appearance, located on visceral or parietal pleura, hyperintense on T1-weighted fat suppressed sequences (Figs. 10, 11). MRI depiction of diaphragmatic or pleural implants of endometriosis can assist with the diagnosis and with the patient’s therapeutic management. Surgery is the choice for patients who are symptomatic or unresponsive to medical therapy. However, surgery requires an experienced surgeon regarding the possibility of treatment of diffuse endometriosis that affects different organs (35).

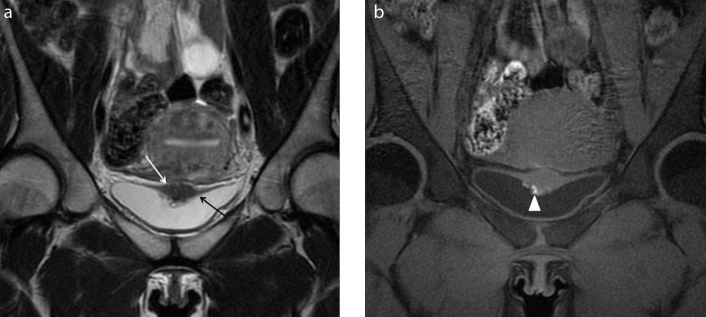

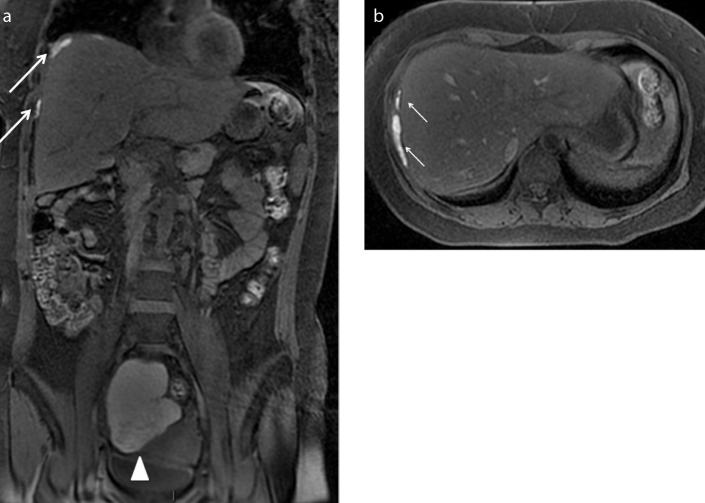

Figure 10. a, b.

A 33-year-old woman with known pelvic endometriosis referring cyclic right shoulder and abdominal pain. Coronal (a) and axial (b) T1-weighted fat-suppressed images show multiple hyperintense areas (white arrows) underneath the diaphragmatic muscular layer adjacent to the right liver lobe, in particular contiguous to the VIIth and the VIIIth segments. The patient has a concomitant voluminous right endometrioma (a, white arrowhead). The endometriotic suspicion of multiple subphrenic implants with liver capsule retraction was confirmed at abdominal surgery.

Figure 11. a–d.

A 30-year-old patient presenting with abdominal pain, weight loss, and tension. She underwent MRI scan of abdomen with suspicion of ovarian malignancy associated with ascites previously documented by ultrasound scan of abdomen. Sagittal T2-weighted (a) and T1-weighted fat-suppressed (b) images on the pelvis show abundant ascites (star) seen as hyperintense signal on both sequences due to hematic component. MRI depicts some peritoneal implants on the left ovarian surface and on the serosal surface of the bladder dome (black arrows), better identified on T1-weighted images as small hyperintense nodules probably indicating endometriotic peritoneal locations. Note the concomitant retro-uterine endometriotic localization, with hemorrhagic component (white arrow). As collateral findings, axial T2-weighted (c) and T1-weighted fat-suppressed (d) images of the upper abdomen demonstrate bilateral pleural effusion (white arrowheads), represented more on the right side. T1-weighted image shows two small nodular implants on the right pleural surface (d, black arrowhead) with hemorrhagic features, suspicious for pleural endometriosis. Abdominal surgery confirmed the suspicion of hemorrhagic ascites with endometriotic peritoneal implants. On the basis of MRI suspicion of pleural involvement, thoracoscopy was also performed revealing multiple endometriotic nodules of right parietal pleura.

Endometriosis with ascites

Pelvic peritoneal endometriosis is not uncommon. However, huge endometriosis peritoneal spread with ascites has been described in only 30–40 cases, more frequently in African American, nulliparous women. Hemorrhagic ascites is exudative as a consequence of peritoneal inflammation reaction and can be due both to the rupture of endometrial cyst and to diffuse endometriosis implants with multiple adhesions and ovarian endometrioma. Symptoms are similar to ovarian neoplasms such as pain and distension of the abdomen, mass, weight loss, and pleural effusion (Fig. 11). This condition can mimic carcinomatosis and can be associated with an increase of CA-125 marker (5, 18).

Conclusion

This article reviews the anatomy and clinical and imaging spectrum of unusual sites of pelvic and extrapelvic endometriotic localizations. The role of MRI in the diagnosis of endometriosis is expanding and so the radiologist should be familiar with the various clinical and imaging representations of typical and atypical localizations when evaluating a patient with clinical suspicion of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Radiologists should consider a wide range of locations in patients with endometriosis and should carefully look, report, and grade the disease, because correct diagnosis is extremely important for appropriate patient management. Laparoscopy continues to be the standard of reference for the diagnosis of endometriosis, but some diagnostic pitfalls include failure to visualize nodules covered by adhesions and subperitoneal disease. Successful treatment requires lesion removal with radical surgery. In this setting, when surgery is indicated, MRI can provide a road map that allows adequate presurgical counseling and guide the surgeon for complete eradication of all possible endometriotic implants.

Main points.

Endometriosis is a systemic disease that affects women in their reproductive age, defined as presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity characterized by intralesional recurrent bleeding during menses. Symptoms are cyclic or chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pain during defecation or urinating; unusual deposits may be associated with more specific symptoms depending on the site of the localization.

Atypical pelvic localizations of endometriosis can occur at the level of the cervix, vagina, round ligaments, ureter, and nerves. Rare extrapelvic endometriosis implants can be localized also in the upper abdomen, in the subphrenic fold or in the subcutaneous fat tissue of the abdominal wall.

MRI is an advantageous technique to detect and stage endometriotic lesions. The MRI signal of endometriotic lesions can be various and is influenced by the age of hemoglobin degradation products. Active endometriosis presents as very bright lesions on T1-weighted images, while later stage endometriosis shows adherences and low-to-intermediate signal intensity lesions on T1- and T2-weighted images.

Since surgery is indicated in most of the cases, MRI can provide a road map of all endometriotic lesions, allowing adequate presurgical counseling and guiding the surgeon for a complete eradication of all implants.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Novellas S, Chassang M, Bouaziz J, Delotte J, Toullalan O, Chevallier EP. Anterior pelvic endometriosis: MRI features. Abdom Imaging. 2010;35:742–749. doi: 10.1007/s00261-010-9600-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-010-9600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegelman ES, Oliver ER. MR imaging of endometriosis: ten imaging pearls. Radiographics. 2012;32:1675–1691. doi: 10.1148/rg.326125518. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.326125518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coutinho A, Jr, Bittencourt LK, Pires CE, et al. MR imaging in deep pelvic endometriosis: a pictorial essay. Radiographics. 2011;31:549–567. doi: 10.1148/rg.312105144. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.312105144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodward PF, Sohaey R, Mezzetti TP. Endometriosis: radiologic–pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2011;21:193–216. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.1.g01ja14193. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.21.1.g01ja14193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett GL, Slywotzky CM, Cantera M, Hecht EM. Unusual manifestations and complications of endometriosis--spectrum of imaging findings: pictorial review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;194:WS34–46. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.7142. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.07.7142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rousset P, Rousset-Jablonski C, Alifano M, Mansuet-Lupo A, Buy JN, Revel MP. Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: CT and MRI features. Clin Radiol. 2014;69:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2013.10.014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinkel K, Frei KA, Balleyguier C, Chapron C. Diagnosis of endometriosis with imaging: a review. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:285–298. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2882-y. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-005-2882-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bazot M, Bharwani N, Huchon C, et al. European society of urogenital radiology (ESUR) guidelines: MR imaging of pelvic endometriosis. Eur Radiol. 2016 Dec 5; doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4673-z. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegelman ES, Outwater E, Wang T, Mitchell DG. Solid pelvic masses caused by endometriosis: MR imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:357–361. doi: 10.2214/ajr.163.2.8037030. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.163.2.8037030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider C, Oehmke F, Tinneberg HR, Krombach GA. MRI technique for the preoperative evaluation of deep infiltrating endometriosis: current status and protocol recommendation. Clin Radiol. 2016;71:179–194. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2015.09.014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veiga-Ferreira MM, Leiman G, Dunbar F, Margolius KA. Cervical endometriosis: facilitated diagnosis by fine needle aspiration cytologic testing. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;4:849–856. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80070-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(87)80070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genc B, Solak A, Sahin N, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging in the evaluation of hormonal cyclic changes in abdominal wall endometriomas. Clin Radiol. 2014;69:130e6. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manganaro L, Porpora MG, Vinci V, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging and tractography to evaluate sacral nerve root abnormalities in endometriosis-related pain: a pilot study. Eur Radiol. 2014;24:95–101. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2981-0. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-013-2981-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaiman S, Gundabattula SR, Pochiraju M, Sangireddy JR. Polypoid endometriosis of the cervix: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289:915–920. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-3112-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-013-3112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doshi J, Doshi S, Sanusi FA, Padwick M. Persistent post-coital bleeding due to cervical endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:468–469. doi: 10.1080/01443610410001696978. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443610410001696978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dallaudière B, Salut C, Hummel V, et al. MRI atlas of ectopic endometriosis. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2013;94:263–280. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2012.10.020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dessole S, Farina M, Rubattu G, et al. Sonovaginography is a new technique for assessing rectovaginal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1023–1027. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04952-x. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(02)04952-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazot M, Darai E, Hourani R, et al. Deep pelvic endometriosis: MR imaging for diagnosis and prediction of extension of disease. Radiology. 2004;232:379–389. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2322030762. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2322030762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crispi CP, de Souza CA, Oliveira MA, et al. Endometriosis of the round ligament of the uterus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2011.09.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redwine DB. Ovarian endometriosis: a marker for more extensive pelvic and intestinal disease. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:310–315. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00211-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gui B, Valentini AL, Ninivaggi V, Marino M, Iacobucci M, Bonomo L. Deep pelvic endometriosis: don’t forget round ligaments. Review of anatomy, clinical characteristics, and MR imaging features. Abdom Imaging. 2004;39:622–632. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0091-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-014-0091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choudhary S, Fasih N, Papadatos D, Surabhi VR. Unusual imaging appearances of endometriosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;192:1632–1644. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1560. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.08.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Tohic A, Chis C, Yazbeck C, Koskas M, Madelenat P, Panel P. Bladder endometriosis: diagnosis and treatment. A series of 24 patients. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2009;37:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2009.01.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gyobfe.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fedele L, Bianchi S, Raffaelli R, Portuese A. Pre-operative assessment of bladder endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2519–2522. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.11.2519. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/12.11.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:194. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-194. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-8-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Exacoustos C, Manganaro L, Zupi E. Imaging for the evaluation of endometriosis and adenomyosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28:655–861. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.04.010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niro J, Fournier M, Oberlin C, Le Tohic A, Panel P. Endometriotic lesions of the lower troncular nerves. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2014;42:702–705. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2014.08.003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gyobfe.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ceccaroni M, Clarizia R, Alboni C, et al. Laparoscopic nerve-sparing transperitoneal approach for endometriosis infiltrating the pelvic wall and somatic nerves: anatomical considerations and surgical technique. Surg Radiol Anat. 2010;32:601–604. doi: 10.1007/s00276-010-0624-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-010-0624-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vercellini P, Chapron C, Fedele L, Frontino G, Zaina B, Crosignani PG. Evidence for asymmetric distribution of sciatic nerve endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:383–387. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00532-5. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006250-200308000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Possover M, Schneider T, Henle KP. Laparoscopic therapy for endometriosis and vascular entrapment of sacral plexus. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:756–758. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.08.048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Head HB, Welch JS, Mussey E, Espinosa RE. Cyclic sciatica. Report of case with introduction of a new surgical sign. JAMA. 1962;180:521–524. doi: 10.1001/jama.1962.03050200005002. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1962.03050200005002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Busard MP, Mijatovic V, van Kuijk C, Hompes PG, van Waesberghe JH. Appearance of abdominal wall endometriosis on MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:1267–1276. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1658-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-009-1658-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hensen JH, Van Breda Vriesman AC, Puylaert JB. Abdominal wall endometriosis: clinical presentation and imaging features with emphasis on sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:616–620. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1619. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.04.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyers MA. Distribution of intra-abdominal malignant seeding: dependency on dynamics of flow of ascitic fluid. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973;119:198–206. doi: 10.2214/ajr.119.1.198. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.119.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Redwine DB. Diaphragmatic endometriosis: diagnosis, surgical management, and long-term results of treatment. Fertil Steril. 2009;77:288–296. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02998-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(01)02998-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirschner PA. Porous diaphragm syndromes. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1998;8:449–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alifano M, Cancellieri A, Fornelli A, Trisolini R, Boaron M. Endometriosis-related pneumothorax: clinicopathologic observations from a newly diagnosed case. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:1219–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.11.044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]