Abstract

Objectives

Alkylating agents have activity in well differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (WD panNETs). In glioblastoma multiforme, decreased activity of O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) predicts response; in panNETs, MGMT relevance is unknown.

Methods

We identified patients with WD panNETs treated with alkylating agents, determined best overall response by RECIST 1.1, and performed MGMT activity testing.

Results

Fifty-six patients were identified; 26/56 (46%) experienced partial response (PR), 24/56 (43%) experienced stable disease (SD), 6/56 (11%) experienced progression of disease (PD). MGMT status was available for 36 tumors. For tumors with PR, 10/15 (67%) were MGMT deficient and 5/15 (33%) were MGMT intact. For tumors with SD, 7/15 (47%) were MGMT deficient and 8/15 (53%) were MGMT intact. For tumors with PD, 3/6 (50%) were MGMT deficient and 3/6 (50%) were MGMT intact.

Conclusions

We observed response and resistance to alkylating agents in MGMT deficient and intact tumors. MGMT status should not guide alkylating agent therapy in WD panNETs.

Keywords: MGMT, alkylating agent, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, neuroendocrine tumors, biomarker

Introduction

Although well differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (WD panNETs) represent only 1–2% of all pancreatic neoplasms, the incidence and prevalence of the disease are rising.1,2 The management of these patients is challenging because of the heterogeneous clinical presentations, and in the past 5 years, several agents have become available for treatment and no studies have evaluated the sequencing of treatment.3 Targeted therapies (somatostatin analogs, sunitinib, everolimus) improve progression free survival, however objective radiographic responses are rare.4–6 Cytotoxic chemotherapy is often used, particularly in patients with high tumor burden and/or more aggressive disease pace.

The alkylating agents temozolomide and dacarbazine are frequently used to treat advanced WD panNETs. Radiographic response rates of 70% have been reported retrospectively, but response rates are lower (about 45%) in prospective small studies.7–11 The mechanism of alkylating agent cytotoxicity is debated, but is thought to occur through DNA methylation at O6-guanine sites.12 O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) is an enzyme located on chromosome 10q26 that repairs these DNA changes, maintaining genomic stability.13 With this understanding, it is hypothesized that high levels of MGMT activity (MGMT intact status) minimize the treatment effects of alkylating agents, resulting in therapy failure. Conversely, reduction in MGMT activity (MGMT deficient status) is thought to increase tumor sensitivity to DNA damage caused by alkylating agents, potentiating the antitumor effects of these drugs.12

In the clinical setting, MGMT status can be evaluated through MGMT protein expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC) or MGMT promoter methylation (a mechanism of MGMT inactivation) assays. A relationship between MGMT status and response to alkylating agents has been most extensively studied in patients with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), where MGMT deficiency is a biomarker for response to therapy as well as improved survival during treatment with temozolomide.14–16

Similar investigation has been undertaken to evaluate for an association between MGMT status and response to alkylating agents in WD panNETs. Three reported studies, however, were limited by their small sample sizes, and yielded conflicting results. 11,17,18 In a more recent investigation which included only panNETs, response to alkylating agent therapy was not influenced by MGMT expression.19

To clarify this issue, we reviewed patients with WD panNETs treated at our institution with alkylating agents. Our hypothesis was that MGMT deficiency was required for response to an alkylating drug. We assessed archived tumor tissue for intact or deficient MGMT status by two methods: IHC and promoter methylation assays. Only WD panNETs were included in this series to maintain a homogeneous patient population.

Materials and Methods

Study Patients

We identified patients with WD panNETs (locally advanced or metastatic) treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) between 3/2007 and 12/2014 from our institutional database. The inclusion criteria were defined as follows: pathologic diagnosis of WD panNET (World Health Organization grade 1, 2, or 3) and treatment with an alkylating agent (specifically, temozolomide or dacarbazine). Medical records were reviewed for patient demographics, pathology reports, and outcomes. Approval for data collection and analysis was obtained from the MSK Institutional Review Board.

Evaluation of response

Best overall response to alkylating agent therapy was determined by a reference radiologist using RECIST 1.1 criteria. Responses were determined by identifying the baseline with the nearest pretreatment imaging (either computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scan) before beginning therapy with an alkylating agent, and assessing response on subsequent scans obtained as part of routine care.

Evaluation of MGMT status in archival tumor tissue specimens

For cases with available tumor tissue, intact or deficient MGMT status was determined by IHC and/or promoter methylation assays. An attempt to perform both assays was made in all available tumor tissue. These assays were performed with the reference pathologist blinded to patient response to therapy.

IHC

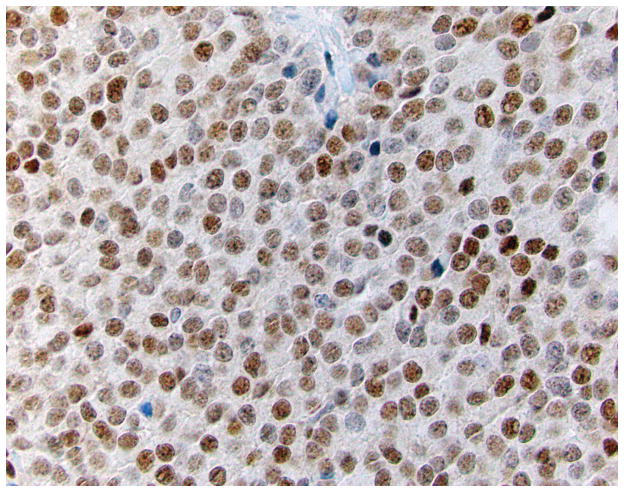

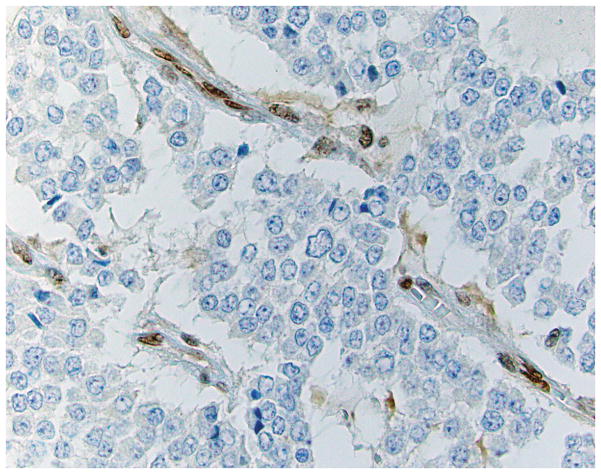

Four micron thick sections were cut from tumor-bearing blocks of each case. Following deparaffinization, an IHC stain for MGMT was performed. A tumor sample known to exhibit intact MGMT expression was used as an external positive control, and non-neoplastic cells in the tumor sample served as an internal positive control. MGMT expression was considered retained when the neoplastic cells exhibited distinct nuclear labeling (Figure 1a). Expression was considered lost when all of the neoplastic cells showed absent nuclear labeling, in the face of positive expression in adjacent non-neoplastic cell nuclei (Figure 1b). In cases with no expression in non-neoplastic cells, the stain was repeated using available alternative tissue blocks; failure to obtain labeling in non-neoplastic cells indicated the stain to be a failure, and no interpretation was rendered.

Figure 1.

IHC labeling of WD panNETs for MGMT. A case with intact immunoexpression (Figure 1a) shows brown nuclear reactivity in the majority of the neoplastic cells. Cases with loss of expression (Figure 1b) show absence of labeling in the neoplastic cells, with preserved expression in adjacent non-neoplastic endothelial cells (400X).

MGMT promoter methylation analysis by pyrosequencing

The assay was designed to detect the level of methylation in a region +28 to +47 from the translation start site (TSS) in exon 1 of the MGMT gene (Ensembl ID: OTTHUMT00000051009). Tumor DNA was extracted and bisulfite-treated using EZ-DNA Methylation Kit™ (Cat#D5020, Zymo Research). A single PCR fragment spanning a part of MGMT exon 1 was amplified and the degree of methylation of five CpG sites was analyzed in a single Pyrosequencing reaction (Qiagen). The PCR products (each 10 μl) were sequenced by pyrosequencing on a PyroMark Q24 Workstation (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The MGMT methylation levels were graded as: if >=4 CpG sites are methylated at >=20%, it was considered methylation present; if three CpG sites were methylated at >=20%, it was considered equivocal; if <=2 CpG sites were methylated at >=20%, it was considered methylation absent.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the clinical characteristics of the patient cohort and the relationship between MGMT status and best response to alkylating agent therapy by RECIST 1.1. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the start of temozolomide or dacarbazine until the time of death. Patients who were alive at the end of the study were censored at the time of the last available follow-up. OS was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier methods. Log- rank test was used to compare OS between MGMT statuses. All p values were based on 2-tailed statistical analysis, and p<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1. A total of 56 patients with WD panNETs (27 females and 29 males) treated with alkylating agents were identified. Six patients (11%) had locally advanced disease at presentation and 50 patients (89%) had metastatic disease. Forty patients (71%) presented with primary tumors in the pancreatic tail. Twenty patients (36%) had low grade tumors, 25 patients (45%) had intermediate grade tumors, and 11 patients (20%) had high grade tumors. Ki-67 proliferation index was available in 44/56 patients (79%); median Ki-67 proliferation index was 10% (range 1% to 80%). Thirteen patients (23%) had functional tumors. Octreoscan™ imaging was performed in 51/56 patients (91%); of those, 49/51 patients (96%) had Octreoscan™ positive disease.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics for the Entire Cohort

| WD panNETs treated with alkylating agents | All (n=56) N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Median age, years | 55 |

| Range | (10–77) |

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Female | 27 (48) |

| Male | 29 (52) |

|

| |

| Performance Status (ECOG) | |

| 0 | 16 (29) |

| 1 | 36 (64) |

| 2 | 4 (7) |

| 3–4 | 0 (0) |

|

| |

| Smoker/prior smoker | 17 (30) |

|

| |

| Primary tumor location | |

| Uncinate | 1 (2) |

| Head | 11 (20) |

| Body | 4 (7) |

| Tail | 40 (71) |

|

| |

| Mean primary tumor size (cm) | 6.1 |

| Range | (0.6–18.0) |

|

| |

| Location of metastases at presentation | |

| Liver | 47 (84) |

| Lymph nodes | 11 (20) |

| Lung | 1 (2) |

| Bone | 4 (7) |

| Adrenal | 2 (4) |

| Ovary | 1 (2) |

| Soft tissue | 4 (7) |

| Other | 4 (7) |

|

| |

| Octreoscan positive | 49/51 (96) patients tested |

|

| |

| Functional | |

| Insulinoma | 3 (5) |

| Gastrinoma | 5 (9) |

| Glucagonoma | 1 (2) |

| VIPoma | 2 (4) |

| Serotonin-secreting | 2 (4) |

|

| |

| Paraneoplastic syndrome at presentation | 2 (4) |

|

| |

| Median Ki-67 proliferation index | 10% (range 1% to 80%) |

Response evaluation

Of the 56 patients, 43/56 patients (77%) received temozolomide and 14/56 patients (25%) received dacarbazine. Best overall response by RECIST 1.1 is summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

WD panNETs Treated With Alkylating Agents: Best Overall Response by RECIST 1.1

| Temozolomide (n = 43) N (%) |

Dacarbazine (n = 13) N (%) |

Total (n = 56) N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Partial Response | 21 (49) | 5 (38) | 26 (46) |

| Stable Disease | 18 (42) | 6 (46) | 24 (43) |

| Progression of disease | 4 (9) | 2 (15) | 6 (11) |

Response by tumor grade

Partial response (PR) was observed in 9/20 (45%) low grade tumors, 12/25 (48%) intermediate grade tumors, and 5/11 (45%) high grade tumors. Stable disease (SD) was observed in 11/20 (55%) low grade tumors, 9/25 (36%) intermediate grade tumors, and 4/11 (36%) high grade tumors. Progression of disease (PD) was observed in 0/20 (0%) low grade tumors, 4/25 (16%) intermediate grade tumors, and 2/11(18%) high grade tumors.

Evaluation of MGMT activity

MGMT activity assays, either IHC and/or promoter methylation testing, were performed in 36/56 tumors (64%). Results are summarized by assay and by MGMT status in Table 3. Testing for MGMT activity was not possible in 20 tumors for the following reasons: insufficient tumor material (15/20 tumors, 75%), unavailable tissue (4/20 tumors, 20%), and test failure (1/20 tumors, 5%).

TABLE 3.

Tumor MGMT Status and Best Overall Response to Alkylating Agent Therapy

| Partial response (N) | Stable disease (N) | Progression of disease (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MGMT IHC negative | 10 | 7 | 3 |

| MGMT IHC positive | 5 | 8 | 3 |

| MGMT promoter methylation negative | 9 | 11 | 4 |

| MGMT promoter methylation positive | 1 | 3 | Not Applicable |

| Any MGMT abnormality (MGMT deficient) | 10 | 7 | 3 |

| No MGMT abnormality (MGMT intact) | 5 | 8 | 3 |

MGMT IHC and response to treatment

IHC testing was available in 36/56 tumors (64%). Testing was negative (indicating loss of protein expression and MGMT deficient status) in 20/36 tumors (55%). Among the 20 tumors with negative testing by IHC, 10/20 tumors (50%) demonstrated a PR, 7/20 tumors (35%) demonstrated SD, and 3/20 tumors (15%) demonstrated PD (Table 3).

MGMT IHC testing was positive (indicating presence of protein expression and MGMT intact status) in 16/36 tumors (44%). Among the 16 tumors with positive testing by IHC, 5/16 tumors (31%) demonstrated a PR, 8/16 tumors (50%) demonstrated SD, and 3/16 tumors (19%) demonstrated PD (Table 3).

MGMT promoter methylation and response to treatment

Promoter methylation testing was available in 28/56 tumors (50%). Testing was negative (indicating absence of promoter methylation) in 24/28 tumors (86%). Among the 24 tumors with negative testing, 9/24 tumors (38%) demonstrated a PR, 11/24 tumors (46%) demonstrated SD, and 4/24 tumors (17%) demonstrated PD.

Testing was positive (indicating presence of promoter methylation and thus, MGMT deficient status) in 4/28 tumors (14%); 1/4 tumors (25%) demonstrated a PR and 3/4 tumors (75%) demonstrated SD.

MGMT IHC and promoter methylation and response to treatment

Both IHC and promoter methylation testing were available in 28/56 tumors (50%). In these 28 tumors, 15 tumors (54%) showed concordance: 3/28 tumors (11%) demonstrated promoter methylation and loss of protein expression and 12/28 tumors (43%) demonstrated protein expression in the absence of promoter methylation. All 3 tumors with promoter methylation and loss of protein expression responded to therapy with an alkylating drug; 1 tumor demonstrated a PR and 2 tumors demonstrated SD. In the 12 tumors with protein expression but no promoter methylation, during treatment with an alkylating agent, 3/12 (25%) tumors demonstrated a PR, 6/12 tumors (50%) demonstrated SD, and 3/12 tumors (25%) demonstrated PD.

There was one discordant case of protein expression despite promoter methylation, and this tumor demonstrated SD with an alkylating agent.

The remaining 12 tumors demonstrated neither protein expression nor promoter methylation; 6/12 tumors (50%) demonstrated a PR, 5/12 tumors (42%) demonstrated SD, and 1/12 tumors (8%) demonstrated PD during alkylating agent therapy.

Responses after Cessation of Alkylation Agent

Because of the risk of significant bone marrow suppression with alkylating drugs (3% risk of myelodysplastic syndrome), no patient in this series was treated with either temozolomide or dacarbazine for more than one year. After completion of one year of alkylating agent therapy, patients who exhibited and maintained either a PR or SD during treatment then entered a treatment break and were actively monitored with follow-up imaging for surveillance. Twenty-seven patients in this cohort entered a treatment break. After cessation of therapy, continued response was observed in 13/27 patients (48%). Of these 13 patients, 1 patient underwent surgical resection of the primary and to date is without evidence of disease and 4 patients remain on a treatment break at this time; median follow-up for these 4 patients, since therapy cessation, is 11.1 months (range 8.1 to 23.5 months). For the remaining 8 patients, the mean duration of treatment response and stabilization was 14.1 months (range 10.2 months to 18.1 months) after therapy with an alkylating agent ended.

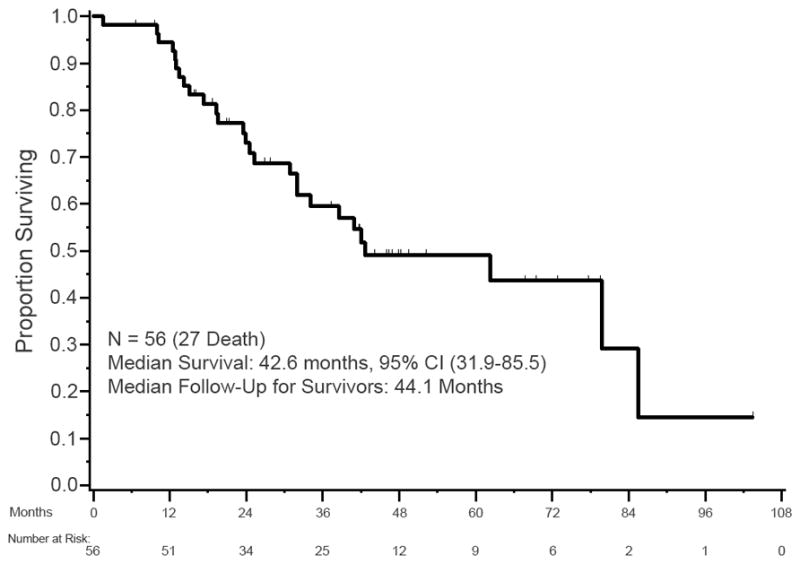

Overall Survival

The median OS of the cohort was 42.6 months (95% confidence interval 31.9 to 85.5 months). Median follow-up for survivors was 44.1 months (Figure 2). There was no significant association between MGMT status and OS (log-rank p=0.47).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier OS of patients with WD panNETs treated with alkylating agents.

Discussion

Our study fails to confirm the hypothesis that MGMT deficiency is required for tumor response to alkylating agents in WD panNETs. In this series, 5 tumors with PR to treatment were MGMT intact (IHC positive for protein expression). Additionally, not all IHC negative tumors responded; PD was seen in 3 IHC negative tumors. Of note, we did observe that all patients whose tumors were promoter methylated, a mechanism of MGMT deficiency, had a PR or SD on treatment, although the sample size was low (n=4). Looking at overall MGMT status regardless of the assay used, we observed PR, SD, and PD in both MGMT intact and deficient tumors that were treated with temozolomide or dacarbazine (Table 3). In addition, unlike prior studies in patients with GBM, we observed no survival difference based on MGMT status in patients with WD panNETs.

Our findings challenge those of prior studies that have suggested that MGMT deficiency is necessary for tumor response. In the earliest study, a retrospective analysis of 36 patients with advanced NETs (12 panNETs) treated with temozolomide was conducted; there were no differences in IHC MGMT expression and response rate.11 This study was questioned, however, given the mixed population that included all WD NETs regardless of site of origin. A second study quantified MGMT deficiency by IHC in 97 archival NET specimens (37 panNETs) and additionally evaluated clinical outcomes in 101 patients (53 panNETs).17 In this second study, 16/21 (76%) panNET specimens treated with temozolomide were MGMT intact and 5/21 specimens (24%) were MGMT deficient; 0/16 MGMT intact tumors responded to treatment and 4/5 MGMT deficient panNET tumors (80%) demonstrated a PR to treatment. The authors of this study concluded that the absence of MGMT may explain the sensitivity of panNETs to alkylating agents but the sample size was small. In a third study of 141 resected panNET specimens, loss of MGMT IHC protein expression was identified in 86/130 specimens (66%), and presence of promoter methylation was identified in 29/52 specimens (56%).18 Concordance between IHC and promoter methylation status was found in 20/41 tumors (49%). Only 10 of those patients were actually treated with temozolomide therapy and no relationship was observed between protein expression and response to temozolomide; however like our study, tumors with promoter methylation showed a high response rate. It is noteworthy, however, that 84% of our cases (20/24 tumors) without promoter methylation also responded to alkylating agents (9 tumors with PR and 11 tumors with SD), again challenging the utility of this biomarker as a basis to eliminate these drugs as treatment options for our patients. The most recent study included 107 patients with NETs of different origins (62 panNETs, 58%), of which 53 patients were treated with alkylating agents; in this investigation, IHC, methyl-specific PCR, and pyrosequencing were used for evaluation of MGMT status. Similar to our findings, in this study, MGMT status was not correlated with OS from diagnosis, but in contrast, progression-free survival and OS from first use of an alkylating agent were significantly higher in MGMT deficient patients.12

What could account for differences between our study and those previously conducted? First, unlike the aforementioned studies, our series included only WD panNETs, while three of the four prior investigations included many NET subtypes. While it is well recognized that alkylating agents are a viable option for treating WD panNETs, the use of these drugs remains controversial for NETs of other anatomic sites, therefore making the conclusions drawn from prior investigations difficult to interpret. Second, small sample sizes in other studies (particularly with regards to tumors that actually were treated with alkylating agents) could also account for differences. Third, there could be differences in the assays used to determine MGMT status. Our methods are similar to other studies, however, and percentages of MGMT protein expression and promoter methylation are within range with prior investigations.12,20,21

Our study showed only partial concordance between MGMT promoter methylation and loss of MGMT protein expression. Given prior data, we hypothesized that the presence of promoter methylation led to loss of protein expression by IHC. In our study, IHC staining and promoter methylation testing were obtained in 28 tumors; 15/28 tumors (54%) demonstrated loss of protein expression, and only 3/15 (20%) tumors were also promoter methylated. This finding of partial concordance has been observed in other tumor types, and is likely due to the existence of other undefined regulatory mechanisms of MGMT expression besides promoter methylation.18,22–24

Additionally, potential differences in MGMT status between the primary site and metastatic lesions were not assessed in this study or in the aforementioned studies; discordances in MGMT expression across metastases within the same patient could contribute to the variable findings. Although one small study suggested MGMT alterations were comparable in primary NETs and their secondary locations, another study showed higher rates of MGMT activity in metastases as compared to the primary lesion.13

In line with prior investigations, we observed that alkylating agents are highly active in panNETs.7,25,26 In this series, using RECIST 1.1, 26/56 patients (46%) experienced a radiographic PR and 24/56 patients (43%) experienced SD. Notably, almost all of the patients included in this series had heavy disease burden and/or disease progression prior to the initiation of alkylating therapy, and more than half of the patient population (36 patients, 64%) had intermediate or high grade tumors. Although only patients with WD tumors were included in our analysis, Ki-67 proliferation index did range from 1% to 80% and we observed responses in the different tumor grades; these findings demonstrate that alkylating agents are active across the spectrum of WD panNETs seen in clinical practice.

Our findings build on a recent investigation evaluating for radiographic and biochemical response in panNETs treated with capecitabine and temozolomide.19 In this study of 143 patients with advanced panNETs, the authors observed a similar overall response rate of 54% by RECIST 1.1, and additionally, in analysis of 52 tumor specimens for MGMT expression and 46 tumors for ALT activation, did not observe a relationship between response to alkylating agent therapy and these potential biomarkers. In this study, evaluation of MGMT status was limited to IHC staining alone, however the high response rate again observed demonstrates the lack of necessity for a biomarker to guide treatment of advanced panNETs with alkylating drugs in the clinical setting.

As noted, in our study, all patients that completed a full year of either temozolomide or dacarbazine and had a PR or SD throughout this period of time went on a treatment break (n=27). Of those 27 patients, 13 patients (48%) continued to have disease response after stopping treatment. This delayed effect of alkylating drugs has never been previously described. Further work to elucidate an ongoing mechanism of action should be investigated in future studies.

In conclusion, although we again observed that alkylating agents have high activity in panNETs, as the majority of patients experienced either a PR or SD on therapy, our study fails to show that MGMT activity, measured by IHC protein expression and/or promoter methylation, is a marker of response or resistance to these agents. Regardless of MGMT intact or deficient status, we observed variable response to alkylating agent therapy, including PR, SD, and PD; we also observed no survival differences in these groups. We conclude that MGMT testing should not be performed in the clinical context, in order to help guide therapy for patients with advanced panNETs. Furthermore, such high response rates to alkylating agents illustrates that there is little value to an enriching biomarker in this setting.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jillian Sue for her role in coordinating tumor MGMT status testing for this project.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: Dr. Diane Reidy-Lagunes has received honoraria and research funding from Novartis. In addition, Dr. Reidy-Lagunes does consulting/advising for Novartis, Ipsen, and Pfizer. Dr. Peter Allen does consulting/advising for Sanofi. In addition, Dr. Allen has received research funding from Novartis. The remaining authors declare no potential conflicts of interest. This work had no specific funding.

Contributor Information

Nitya Raj, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York.

David S. Klimstra, Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York.

Natally Horvat, Department of Radiology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York.

Liying Zhang, Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York.

Joanne F. Chou, Department of Biostatistics, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York.

Marinela Capanu, Department of Biostatistics, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York.

Olca Basturk, Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York.

Richard Kinh Gian Do, Department of Radiology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York.

Peter J. Allen, Department of Surgery, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York.

Diane Reidy-Lagunes, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY.

References

- 1.Dumlu EG, Karakoc D, Ozdemir A. Nonfunctional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Advances in Diagnosis, Management and Controversies. Int Surgery. 2015;100:1089–1097. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-14-00204.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metz DC, Jensen RT. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors: pancreatic endocrine tumors. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1469–1492. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, et al. One hundred years after “Carcinoid”: Epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063–3072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raymond E, Dahan L, Raoul JL, et al. Sunitinib malate for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:501–513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:514–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caplin ME, Pavel M, Ruszniewski P. Lanreotide in metastatic enteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1556–1557. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1409757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramanathan RK, Cnaan A, Hahn RG, et al. Phase II trial of dacarbazine (DTIC) in advanced pancreatic islet cell carcinoma. Study of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-E6282. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1139–1143. doi: 10.1023/a:1011632713360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fine RL, Gulati AP, Krantz BA, et al. Capecitabine and temozolomide (CAPTEM) for metastatic, well-differentiated neuroendocrine cancers: The Pancreas Center at Columbia University experience. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:663–670. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2055-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strosberg JR, Fine RL, Choi J, et al. First-line chemotherapy with capecitabine and temozolomide in patients with metastatic pancreatic endocrine carcinomas. Cancer. 2011;117:268–275. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulke MH, Stuart K, Enzinger PC, et al. Phase II study of temozolomide and thalidomide in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:401–406. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekeblad S, Sundin A, Janson ET, et al. Temozolomide as monotherapy is effective in treatment of advanced malignant neuroendocrine tumors. Clinical Cancer Res. 2007;13:2986–2991. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walter T, van Brakel B, Vercherat C, et al. O-6-Methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase status in neuroendocrine tumours: prognostic relevance and association with response to alkylating agents. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:523–531. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christmann M, Verbeek B, Roos WP, et al. O(6)-Methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) in normal tissues and tumors: enzyme activity, promoter methylation and immunohistochemistry. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1816:179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Godard S, et al. Clinical trial substantiates the predictive value of O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase promoter methylation in glioblastoma patients treated with temozolomide. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1871–1874. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hegi ME, Diserens A, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulke MH, Hornick JL, Frauenhoffer C, et al. O-6-Methylguanine DNA Methyltransferase Deficiency and Response to Temozolomide-Based Therapy in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:338–345. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmitt AM, Pavel M, Rudolph T, et al. Prognostic and predictive roles of MGMT protein expression and promoter methylation in sporadic pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2014;100:35–44. doi: 10.1159/000365514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cives M, Ghayouri M, Morse B, et al. Analysis of potential response predictors to capecitabine/temozolomide in metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016;23:759–767. doi: 10.1530/ERC-16-0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu L, Broaddus RR, Yao JC, et al. Epigenetic alterations in neuroendocrine tumors: methylation of RAS-association domain family 1, isoform A and p16 genes are associated with metastasis. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1632–1640. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnold CN, Sosnowski A, Schmitt-Graff A, et al. Analysis of molecular pathways in sporadic neuroendocrine tumors of the gastro-entero-pancreatic system. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:2157–2164. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weller M, Stupp R, Reifenberger G, et al. MGMT promoter methylation in malignant gliomas: ready for personalized medicine? Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:39–51. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quillien V, Lavenu A, Karayan-Tapon L, et al. Comparative assessment of 5 methods (methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction, MethyLight, pyrosequencing, methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting, and immunohistochemistry) to analyze O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltranferase in a series of 100 glioblastoma patients. Cancer. 2012;118:4201–4211. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wick W, Weller M, van den Bent M, et al. MGMT testing--the challenges for biomarker-based glioma treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:372–385. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kouvaraki MA, Ajani JA, Hoff P, et al. Fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and streptozocin in the treatment of patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic endocrine carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4762–4771. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moertel CG, Lefkopoulo M, Lipsitz S, et al. Streptozocin-doxorubicin, streptozocin-fluorouracil or chlorozotocin in the treatment of advanced islet-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:519–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202203260804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]