Abstract

Background

Support for the legalization of recreational marijuana continues to increase across the United States and globally. In 2016, recreational marijuana was legalized in the most populous US state of California, as well as three other states. The primary aim of this study was to examine trends in support for recreational marijuana legalization in Washington, a state which has had legal recreational marijuana for almost four years, using data collected over the four years post-legalization. A secondary aim was to examine trends in support for the cultivation of marijuana for personal use.

Methods

Data come from geographically representative general population samples of adult (aged 18 and over) Washington residents collected over five timepoints (every six months) between January 2014 and April 2016 (N = 4,101). Random Digit Dial was used for recruitment. Statistical analyses involved bivariate comparisons of proportions across timepoints and subgroups (defined by age, gender, and marijuana user status), and multivariable logistic regression controlling for timepoint (time) to formally test for trend while controlling for demographic and substance use covariates. All analyses adjusted for probability of selection.

Results

Support for legalization in Washington has significantly increased: support was 64.0% (95% CI: 61.2%–67.8%) at timepoint 1 and 77.9% (95% CI: 73.2%–81.9%) at timepoint 5. With each six months’ passing, support increased 19% on average. We found no statistically significant change in support for home-growing.

Conclusions

Support for marijuana legalization has continued to significantly increase in a state that has experienced the policy change for almost four years.

Keywords: marijuana, cannabis, legalization, policy, public opinion

1. INTRODUCTION

The legalization of recreational marijuana sales and use has become a highly debated policy topic in recent years, especially in the US, although scientific research on the effects of these policies is very limited (Kim et al., 2016; Mason et al., 2016). Still, support for legalization of recreational marijuana continues to increase across the United States and globally (Cruz et al., 2016; Galston and Dionne, 2013). In 2016, recreational marijuana was legalized in the most populous US state of California, as well as Massachusetts, Maine, and Nevada. More states and other countries such as Canada are expected to consider recreational legalization in 2017 and beyond making the experiences of US states with existing regulatory systems highly relevant.

While US states have experienced “bottom-up” approaches to legalization, with marijuana legislation generally initiated and voted on by the public, Uruguay undertook a “top-down” approach in which the government legalized marijuana production and distribution in 2012 despite widespread public opposition (Cruz et al., 2016). The Latin American Public Opinion Project found that in 2014, 51.5% of those interviewed in the US supported legalization, while only 34% of those interviewed in Uruguay favored legalization; this underscores the fact that changing a policy does not necessarily change the majority opinion (Cruz et al., 2016).

1.1. National support for the legalization of marijuana and other substance use

Support for marijuana legalization has increased nationally as well as in Washington state. A 2016 Gallup poll found that 60% of Americans favor legalization, an all-time high in the 47 years Gallup has polled on this issue (Swift, 2016). Interestingly, national support for legalization went from 43% in 2012 to 55% in 2014 (ORC International, 2014), which is similar to the magnitude of the increase in support in Washington during that same time period (Subbaraman and Kerr, 2016). Furthermore, among the same 2014 CNN survey respondents, 81% said alcohol should be legal; 73% said alcohol is more dangerous than marijuana; 16% thinking drinking alcohol is morally wrong; and 35% said smoking marijuana is morally wrong. Thus, there appear to be complicated and perhaps contradictory relationships between perceptions of risk and morality when compared with opinions on public policy regarding substance use.

The only analogous substance policy shift to marijuana legalization is the end of prohibition of alcohol, which was in effect in America from 1920–1933. Six years after Prohibition, a 1939 Gallup poll showed that 30% of respondents favored making the country “dry again ”(Gallup Organization, 1939). In 1984, only 17% of Gallup poll respondents were in favor of a law prohibiting alcohol sales (Gallup Organization, 1984); this number grew to 30% in 1988 according to a poll by ABC news (ABC News, 1988). On the other hand, in 1988, only 9% thought drugs should be legal (ABC News, 1988); this number grew to 30% in 1990 according to an Los Angeles Times poll, and then went back down to 15% in 1994 according to CBS news (CBS News, 1994). Importantly, these polls were carried out by different institutions and might not be directly comparable. Still, the support for the legalization of other substance use is relevant for context.

For example, in a 2014 poll conducted by YouGov/The Huffington Post (Moore, 2014) regarding the legalization of methamphetamine, MDMA, LSD, peyote, ayahuasca, and ibogaine, support for legalization ranged from 8% (LSD) to 12% (ibogaine). Similarly, support for other drugs (specifically psilocybin mushrooms, LSD, MDMA, ibogaine, cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine) ranged from 12% (ibogaine) to 22% (psilocybin mushrooms) in a poll conducted by the marketing firm (Lopez, 2016). These polls indicate that while Americans lean towards favoring marijuana legalization, they do not want to legalize all drug use.

1.2. Rationale for current study

In the US, four states have retail systems for marijuana regulation that are legal at the state level. The experiences and opinions of residents of these states are highly relevant to the issue of legalization. An important question for places considering these policies is whether support grows over time or declines as residents experience any positive or negative impacts individually or societally. The state of Washington legalized marijuana through voter initiative in November of 2012, with retail stores first opening in July of 2014. Washington took a relatively cautious approach to regulation of legal sales compared to other legal marijuana states, for example by banning vertical integration in order to avoid monopolization of the marijuana market, limiting the number of retail stores and requiring explicit approval of any processed marijuana products.. Only one study has examined support for legalization in Washington through 2014 (Subbaraman and Kerr, 2016), which found continued support in the two years post-legalization with nearly 20% of those who voted against the initiative now supporting it. However, given the limited experience with the new regulatory system and retail marijuana sales in 2014, there is a need for information on support for legalization in 2015 and 2016, by which time residents had over a year of experience with retail stores and three full years of legal recreational marijuana. This paper updates previous results regarding support for legalization by including data collected through April of 2016. This paper also extends previous findings by examining support for home cultivation, which currently remains a felony in Washington though not in other legal marijuana states, and by investigating potential subgroup differences in support, as other studies have shown that demographic factors like age and sex, as well as marijuana use, are related to opinions about marijuana (Cruz et al., 2016; Subbaraman and Kerr, 2016).

2. METHODS

2.1. Data

Data come from repeated cross-sectional general population samples of adult (aged 18+) Washington state residents collected over five timepoints (every six months) between January 2014 and April 2016. After combining timepoints, the total sample size was 4,101 (1,202 from T1; 804 from T2; 823 from T3; 662 from T4; 610 from T5). List-assisted Random Digit Dial proceedures were used to recruit the sample, with > 40% from cell phones. The decreasing sample size was by design in relation to funding constraints. The American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR2) cooperation rates were 50.9% (landline) and 60.9% (cell phone) in T1; 45.8% (landline) and 62.4% (cell) in T2; 43.7% (landline) and 61.5% (cell) in T3; 41.7% (landline) and 59.6% (cell) in T4; and 49.4% (landline) and 60.9% (cell) in T5; AAPOR has detailed formulas for cooperation rates that can be found on their website (The American Association for Public Opinion Research, 2000). The Public Health Institute’s Institutional Review Board approved this study, and we obtained informed consent from all participants.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcomes and exposure

Our primary outcome support for legalization was based on the question, “Do you think marijuana should be legal for adults?” We also examined possible trends in support for home-growing based on the question, “Do you think adults should be able to grow their own marijuana for personal use?” Answer options were yes, no, I don’t know, and refused. Because we were interested in trends, our primary independent variable was the data collection timepoint (W1-W5), with each additional timepoint representing the passage of approximately six months’ time.

2.2.2. Covariates

As covariates, we included marijuana user status (lifetime abstainer, past, current), based on the questions “Have you ever used marijuana at any time in your life?” and “How often have you used marijuana, hash, or pot during the last twelve months?” (those who had used at least once in the last 12 months were classified as current); and drinking status (lifetime abstainer, past, current) which was assessed similarly. We also included perceptions of riskiness based on the question, “How risky do you think weekly marijuana use is for a person’s health?” (very, somewhat, a little, not at all, or good for health). We also controlled for gender, age (18–29, 30–49, 50+ years old), race/ethnicity (White, African American, Hispanic, Other), education (high school diploma or less, some college, college graduate, graduate school), and employment (full- or part-time employed vs. unemployed/retired/homemaker/student). Using zip code data, we also classified whether respondents lived in Eastern vs. Western Washington; location data was important to include in the analyses given that Eastern and Western Washington tend to differ politically.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

First, in order to show that the sample was geographically state-representative within and across timepoints, we compared the proportion of respondents from Eastern vs. Western Washington for each timepoint. Next, for each timepoint, we calculated proportions of respondents in favor of marijuana legalization both in the sample overall and within subgroups defined by gender, age, and marijuana user status. We calculated proportions of support for home-growing similarly. We used 95% confidence intervals for subgroup proportions to determine significant differences across groups and timepoints. We then used multivariable logistic regression controlling for timepoint to formally test for trends while controlling for covariates as well as three interactions terms: timepoint*sex, timepoint*age, and timepoint*marijuana use status. These interaction terms represent potential differences in how support for legalization has changed over time within subgroups (i.e., sex, age, marijuana user subgroups). All analyses adjusted for probability of selection due to the sampling design through survey weights, and were performed in Stata V.13, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA. Sampling weights accounted for differential probability of response between landline and cell phone samples including such factors as having more than one landline and whether those recruited by cell phones also have a landline and their proportionate use of each. Weights also included post-stratification weights for age, gender, race/ethnicity and educational attainment demographics based on the Washington general population from the 2010 Census.

3. RESULTS

In terms of state-representativeness, we found that at each timepoint, the proportion of respondents from Eastern WA was 24%–26%, and the proportion from Western WA was 74%–76%. This is consistent with the 2010 census, in which Western Washington had a population of 5,229,486, 78% of the total state population of 6,724,540 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

3.1. Bivariate results

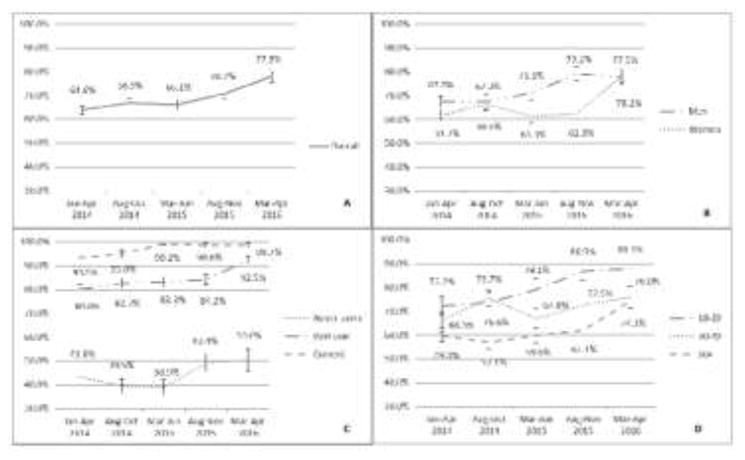

The first column of Table 1 describes the sample distribution of demographic and substance use variables. Figure 1 shows how support for legalization has changed over time in the aggregate sample (Panel A); across marijuana user groups (Panel B); among men and women (Panel C); and across age groups (Panel D). By comparing 95% confidence intervals and observing no cross-over, we see that overall support for legalization significantly increased from 64.6% (95% CI: 61.2%–67.8%) at T1 (early 2014) to 77.9% (95% CI: 73.2%–81.9%) at T5 (early 2016). Within marijuana user subgroups, all three groups differed significantly in support at each time-point, with the never users having the most variation and biggest increase over time. Men and women differed significantly in support at T1, with 67.5% (95% CI: 62.5%–72.1%) of men and 61.7% (95% CI: 57.1%–66.2%) of women supporting, yet converge by T5 with 77.5% (95% CI: 70.4%–83.3%) of men and 78.2% (95% CI: 71.9%–83.5%) of women supporting. The three age groups also start at T1 with significantly different levels of support (72.2% among 18–29 (95% CI: 64.2%–79.0%); 66.3% among 30–49 (95% CI: 59.8%–72.2%); 59.5% among 50+ year olds (95% CI: 54.9%–64.0%)), with the older groups later converging at 76.0% (95% CI: 65.7%–84.0%) and 74.3% (95% CI: 68.4%–79.5%) respectively. The youngest respondents retained significantly higher support than older at T5, with 88.1% (95% CI: 78.3%–93.8%) supporting legalization.

Table 1.

Survey-weighted sample distribution and adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals from logistic regressions of time (Wave) on Support for Marijuana Legalization (N = 4,101)

| Predictor | % | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Timepoint (vs. Timepoint 1) | -- | 1.19 (1.09, 1.30)*** |

| Male (vs. Female) | 49.6 | 1.00 (0.78, 1.29) |

| Age (vs. 18–29 years old) | ||

| 30–49 | 34.1 | 0.64 (0.40, 1.01) |

| 50+ | 43.9 | 0.61 (0.39, 0.95)* |

| Education (vs. High school graduate or less) | ||

| Some college | 34.3 | 1.10 (0.77, 1.56) |

| College graduate | 17.3 | 1.14 (0.86, 1.63) |

| Graduate school or more | 13.7 | 1.24 (0.88, 1.74) |

| Employment (vs. Full or part-time) | ||

| Unemployed/Retired/Homemaker/Student | 40.9 | 0.96 (0.72, 1.28) |

| Race (vs. White) | ||

| African American | 4.5 | 2.91 (1.62, 5.21)*** |

| Hispanic | 9.5 | 0.90 (0.44, 1.83) |

| Other | 11.1 | 0.92 (0.57, 1.48) |

| Marijuana use status (vs. Lifetime abstainer) | ||

| Past user (no use in past 12 months) | 34.7 | 2.96(2.28, 3.84)*** |

| Used marijuana in past 12 months | 27.2 | 19.01 (10.63, 34.01)*** |

| Drinking status (vs. Lifetime abstainer) | ||

| Past drinker (no use in past 12 months) | 22.6 | 1.52 (0.92, 2.51) |

| Used alcohol in past 12 months | 70.0 | 1.32 (0.77, 2.28) |

|

Do you think that marijuana use should be legal for adults? (vs. No) Yes I don’t know |

||

| 69.3 | -- | |

| 4.6 | -- | |

| Do you think adults should be able to grow marijuana for their own personal use? (vs. No) | ||

| Yes | 62.2 | -- |

| I don’t know | 3.7 | -- |

| How risky do you think weekly MJ use is for a person’s health? (vs. Very) | ||

| Somewhat | 23.5 | 6.65 (4.69, 9.42)*** |

| A little | 23.5 | 20.48 (13.50, 31.07)*** |

| Not at all | 20.6 | 38.09 (21.25, 68.30)*** |

| Good for health | 9.3 | 38.13 (16.85, 86.28)*** |

| I don’t know | 5.0 | 9.24 (5.18, 16.49)** |

| Location (vs. Eastern Washington) | ||

| Western | 75 | 1.12 (0.86, 1.47) |

Figure 1.

Trends in support for marijuana legalization in Washington state, January 2014-April 2016

Panel A: Sample overall

Panel B: Gender-stratified

Panel C: Marijuana user status-stratified

Panel D: Age-stratified

We found no statistically significant change in support for home-growing between timepoints 1 and 5: at T1, support for home-growing was 59.3% (95% CI: 55.8%–62.7%) and at T5 it was 68.0% (95% CI: 62.6%–72.9%). Within subgroups, the only significant differences were across marijuana user groups: at T5, never users were 42.9% in support (95% CI: 34.4%–51.8%), past users were 71.8% in support (95% CI: 61.9%–79.9%), and current users were 90.5% in support (95% CI: 80.6%–95.6%). There were no significant changes in support for home-growing within subgroups across time.

3.2. Multivariable regression results

The second column of Table 1 displays results from the multivariable model regressing support for legalization on study timepoint and covariates. Timepoint was related to significantly increased support in that the odds of a respondent expressing support for legalization increased an average of 19% with each additional six months’ passing, indicating a significant increasing trend. Other significant predictors of support include younger age (18–29 vs. 50+), being African American (vs. White), past or current marijuana use (vs. never use), and lower perceptions of risk from marijuana use (vs. viewing it as very risky). Education, employment, and alcohol use were not related to support for marijuana legalization.

There was no significant trend for support for home-growing in the multivariable model (OR = 1.07, 95% CI: 0.98, 1.17). The relationships between covariates and home-growing support were similar to the relationships between covariates and legalization support (results not shown). There were also no significant interactions between timepoint and subgroups (results not shown), so these terms were removed from the final models for parsimony.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Summary of results

In a large, general population survey from a state which has had legalized recreational marijuana for almost four years, the longest of any US state, we found a significant increase in support for legalization as evidenced in both bivariate and multivariable tests. Marijuana retail stores had been open for more than a year and a half by the 2016 survey, suggesting that the stores have not negatively influenced support for the policy change. With each six months’ passing between January 2014 and April 2016, support increased 18% on average. Women surpass men in support by T5 although this difference was not significant. Support has also increased among 18–29, 30–49, and 50+ year old age groups, though the increases are also not statistically significant when examining 95% confidence intervals. High levels of support among current and past users were not surprising; however, the increasing levels among never users were not necessarily expected. The biggest jump in support among never users occurred in the summer of 2015, a full year after the retail stores opened in July 2014. Perhaps non-users are perceiving advantages besides the freedom to use marijuana without penalty.

4.2. Potential advantages of legalizing marijuana

The potential unforeseen advantages could explain why voters who voted against I-502 in 2012 are in favor of legalization in 2016, and are relevant for states that are considering shifting to legalization as well. For example, proponents of legalization claim that legalization benefits society as a whole because of job creation in the new marijuana industry, revenues to the state, increases in tourism and related jobs, and reduced criminal justice activity. Being viewed as a leader in liberalized marijuana policy, which might be amplified through tourism, could also contribute to positive perceptions of legalization in Washington.

4.3. Home-growing marijuana for personal recreational use

While the majority of respondents supported legal home-growing in each survey, we found no evidence for increases in support, which could be due to its ongoing illegality. Currently, Washington does not permit growing marijuana for personal recreational use, and still considers it a felony. This widely differs from Colorado and Alaska, which each allow up to six plants, as well as Oregon, which allows up to four plants for personal recreational use. These differences highlight the variation in marijuana laws even in states with legalized use.

4.4. Limitations

A key study limitation is that some public health effects, e.g., negative effects of smoking or increases in neurodevelopmental problems in adolescents, could take more time to develop. Furthermore, the inherent delay in research studies in documenting changes in use and problems post-legalization means that residents currently do not have substantial objective information; the opinions expressed are based on their experiences and perhaps the absence of visible, immediate, or dramatic changes in marijuana-related problems. Data were collected cross-sectionally and may be affected by reporting biases, such as the social acceptability of supporting current laws, or by changes in the characteristics of non-response. Furthermore, an alternate explanation for the increased support could be that marijuana is currently legal, and there may be people who simply go with the status quo. We were unable to measure changes in support as a function of the density of marijuana retail stores, which might be a stronger test of whether the opening of this market influences attitudes. Future plans include geo-referencing of the surveys and geo-spatial analyses. Finally, Washington’s population may have characteristics that limit generalizability to other states and countries.

4.5. Conclusion

Support for marijuana legalization has continued to increase in a state that has experienced the policy change for almost four years. Support reached 78% by April 2016, which is relatively high compared to policies related to alcohol use (Greenfield et al., 2006) and substantially higher than the national average level of 60% in support for recreational marijuana legalization (Swift, 2016). The increases in support among former and never marijuana users are particularly notable, and suggest that legalization might be achieving benefits beyond simply permitting marijuana use. Whether the increasing trends in support for marijuana legalization will bear out in other states, especially in states with current legal regimes, remains to be seen.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Support for marijuana legalization increased in Washington State to 78% in 2016.

Support increased within all subgroups defined by sex, age, and marijuana use.

Support for home-growing, which remains illegal in Washington, has not changed.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This work was funded by grant NIAAA R01 AA021742 from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

The authors gratefully acknowledge their funding source above, as well as all survey respondents.

Footnotes

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:...

Contributors

Meenakshi Sabina Subbaraman did the statistical analyses, managed the literature search, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. William Kerr was the PI of the grant, developed the research question, and assisted with interpreting the results and editing the final manuscript. Both authors have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared by either author.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- ABC News. Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, iPOLL. Cornell University; Ithaca, NY: 1988. [accessed Jan-4-2017]. ABC News Poll [All drugs should be illegal?] USABC.091388.R19. [Google Scholar]

- CBS News. Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, iPOLL. Cornell University; Ithaca, NY: 1994. [accessed Jan-4-2017]. CBS News Poll [Some people feel that current drug laws haven’t worked, and that drugs like marijuana, cocaine, and heroin should be legalized and subject to government regulation and taxation like alcohol and tobacco. Do you think drug legalization is a good idea or a bad idea?] USCBS.080394.R02. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz JM, Queirolo R, Boidi MF. Determinants of public support for marijuana legalization in Uruguay, the United States, and El Salvador. J Drug Issues. 2016;46:308–325. [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM, Mendelson B, Berkes JJ, Suleta K, Corsi KF, Booth RE. Public health effects of medical marijuana legalization in Colorado. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup Organization. Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, iPOLL. Cornell University; Ithaca, NY: 1939. [accessed Jan-4-2017]. Gallup Poll [If the question of national prohibition should come up again, would you vote to make the country dry?] USGALLUP.180A.QA01. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup Organization. Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, iPOLL. Cornell University; Ithaca, NY: 1984. [accessed Jan-4-2017]. Gallup Poll (AIPO) [Would you favor or oppose a law forbidding the sale of all beer, wine and liquor throughout the nation?] USGALLUP.1237.Q08. [Google Scholar]

- Galston WA, Dionne EJ., Jr . The Brookings Institution; Washington, DC: 2013. [Accessed: 2016-09-22]. The new politics of marijuana legalization: why opinion is changing. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6kiSLAVpD] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Ye Y, Giesbrecht NA. Alcohol policy opinions in the U.S. over a 15-year period of dynamic per capita consumption changes: implications for today’s public health practice. KBS Thematic Symposium: Population Level Studies on Alcohol Consumption and Harm; October 1–5; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, Weier M. Assessing the public health impacts of legalizing recreational cannabis use in the USA. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;97:607–615. doi: 10.1002/cpt.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfer C. Implications of marijuana legalization for adolescent substance use. Subst Abuse. 2014;35:331–335. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.943386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Wall M, Cerdá M, Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, Galea S, Feng T, Hasin DS. How does state marijuana policy affect US youth? Medical marijuana laws, marijuana use and perceived harmfulness: 1991–2014. Addiction. 2016;111:2187–2195. doi: 10.1111/add.13523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Hall KE, Genco EK, Van Dyke M, Barker E, Monte AA. Marijuana tourism and emergency department visits in Colorado. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:797–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1515009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez G. [Accessed: 2017-01-03];Poll: the only drug Americans want to legalize is marijuana. 2016 Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6nFUvxhUl.Vox.

- Mason WA, Fleming CB, Ringle JL, Hanson K, Gross TJ, Haggerty KP. Prevalence of marijuana and other substance use before and after Washington State’s change from legal medical marijuana to legal medical and non-medical marijuana: cohort comparisons in a sample of adolescents. Subst Abuse. 2016;37:330–335. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1071723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Samples H, Bandara S, Saloner B, Bachhuber M, Barry CL. The emerging public discourse on state legalization of marijuana for recreational use in the US: analysis of news media coverage, 2010–2014. Prev Med. 2016;90:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore P. Poll results: drugs. YouGov US; 2014. [Accessed: 2017-01-03]. Front Page. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6nFTkhU2b. [Google Scholar]

- ORC International. CNN/ORC Poll (Marijuana legalization) Princeton, NJ: 2014. [Accessed: 2017-01-03]. p. 19. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6nFPZqRFr. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. America’s new drug policy landscape: two-thirds favor treatment, not jail, for use of heroin, cocaine. Washington, DC: 2014. [Accessed: 2017-01-03]. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6nFVOI8i6. [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraman MS, Kerr WC. Marijuana policy opinions in Washington state since legalization: would voters vote the same way? Contemp Drug Probl. 2016;43:369–380. doi: 10.1177/0091450916667081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift A. Support for legal marijuana use up 60%. Gallup, Inc; Washington, DC: 2016. [Accessed: 2017-01-03]. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6nFNcH2R7. [Google Scholar]

- The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. The American Association for Public Opinion Research; Ann Arbor, MI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Estimates of the Resident Population by Selected Age Groups for the United States, States, and Puerto Rico. American FactFinder; 2010. [Accessed: 2011-10-11]. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/62MgE3woA. [Google Scholar]

- Wall MM, Mauro C, Hasin DS, Keyes KM, Cerdá M, Martins SS, Feng T. Prevalence of marijuana use does not differentially increase among youth after states pass medical marijuana laws: commentary on and reanalysis of US National Survey on Drug Use in Households data 2002–2011. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;29:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.