Abstract

Adverse drug reactions still pose an important clinical problem. Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) is an enzyme that regulates 5-FU quantities available for anabolic processes and hence affects its pharmacokinetics, toxicity and efficacy.

There are several studies describing a hereditary (pharmacogenetic) disorder in which individuals with absent or significantly reduced DPD activity may even develop a life-threatening toxicity following exposure to 5-FU. The most common mutation is known as the DPYD*2A or as the splice-site mutation (IVS14 + 1G A) leading to creation of a dysfunctional protein. An objective behind the study was to ascertain existence of the IVS14+ 1G A mutation among the population of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Our research has undeniably attested to existence of one heterozygote for the DPYD gene mutation, i.e. one heterozygote for IVS14 + 1 G > A, DPYD*2A mutation.

Keywords: pharmacogenetics, Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, DPYD2A mutation

INTRODUCTION

Adverse drug reactions still pose an important clinical problem. Therein, it was estimated that in the last decade alone they caused over 100,000 deaths annually in the United States. As such, these reactions were the fourth leading cause of deaths in the U.S., immediately after hearth diseases, malignancies and strokes (1). There is a direct link between therapeutical effects and toxicity of 5-FU and the drug’s anabolic process related to nucleotides. In turn, this may inhibit activities of thymidylate synthetase or incorporate 5-FU into RNA and/or DNA. More than 85% of the 5-FU dosage administered to human subjects was degraded through catabolic pathways, meaning that only app. 15% of the dosage was left to the anabolic process. In the past ten years it became clear that the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) is an enzyme that regulates 5-FU quantities available for anabolic processes and hence affects its pharmacokinetics, toxicity and efficacy. The 5-FU anabolism leads to creation of 5 fluoro2’- deoxyuridine-5’-monophosphate (FdUMP), which is a cytotoxic product of a multilevel activation pathway of the 5-FU. FdUMP acts as an inhibitor of the thymidylate synthetase (TS), thus causing an intracellular accumulation of the deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP) and a reduction in a level of deoxythymidine monophosphate (dTMP). Finally, this induces an arrest of a DNA synthesis. The initial and rate-limiting enzyme in the catabolism of the 5-FU is dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) that catalyses a 5-FU reduction into 5,6-dihydrofluorouracil (DHFU). Then on, DHFU is degraded down to fluoro-P-ureido propionic acid (FUPA) and flouro-P-alanine (FBAL) (2). There are several studies describing a hereditary (pharmacogenetic) disorder in which individuals with absent or significantly reduced DPD activity may even develop a life-threatening toxicity following exposure to 5-FU. Here we need to consider the non-functional catabolic pathway due to a DPD inability to metabolise. Many studies, of which the most important are the ones by Van Kuilenburg and Johnson, have indicated that a high rate of the 5-FU toxicity is attributable to the reduced DPD activity (3). Van Kuilenburg has found that 59% of oncological patients with 5-FU toxicity have also shown signs of reduced DPD activity, while Johnson (4) saw this frequency to be 43%, thereof app. 12% having profound and app. 13% partial DPD deficiency. These patients are likely to develop an unanticipated toxic reaction subsequent to being treated with the 5-FU. When given in standard doses and coupled with altered pharmacokinetics, 5-FU may lead to severe toxic reactions like mucositis, granulocytopenia, neuropathy, diarrhea and even death in the worst-case scenario. A cause to this toxicity seems to be in a decreased drug clearance hence resulting in an extended 5-FU exposure. DPD-deficient patients exhibit a normal phenotype until such time they have been administered with the 5-FU. It has been estimated that nearly 3-5% of the general population have the DPD activity below 95% (<0,064 nmol/min/mg for frozen samples) of the lower limit for the normal population (5). It has been reported that 55% of patients with reduced DPD activity suffers from the grade 4 neutropenia, as opposed to 13% of patients with normal DPD activity (P = 0,01) (6). Moreover, the toxicity occurs much earlier with regards to patients with low DPD activity (10,0 ± 7,6 versus 19,1 ± 15,3 days, P < 0,05). The patients suffering from the severe 5-FU toxicity have exhibited more than 30 mutations in the DPYD gene to include one G to A mutation in the 5’-splice recognition site of intron 14 that resulted in a 165-bp deletion that correspond to exon 14. This mutation is known as the DPYD*2A as per defined nomenclature or as the splice-site mutation (IVS14 + 1G A) leading to creation of a dysfunctional protein (7). The mutation was not only the first one to be analysed, but also the most frequently observed of all mutations in the population studies (app. 52%) (8).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the local ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient. This experimental research was designed as a prospective, open and translation study. The study was performed among patients of the Oncology Clinic of the University of Sarajevo Clinics Centre treated in the period from 2006-2007. An objective behind the study was to ascertain existence of the IVS14 + 1G ^ A mutation among the population of Bosnia and Herzegovina. A test group observed in the subject-matter research consisted of 50 subjects - patients at the Oncology of the University of Sarajevo Clinics Centre that have undertaken chemotherapy and been treated with 5-FU or Capecetabine in the period from 2006 to 2007. Therein, we have done a genomic analysis of DPYD gene for these patients. These patients were also divided into two subgroups regarding presence of toxicity grade 3 or 4 or without toxicity after administration of 5 FU. All genotype analysis were conducted on samples of the patients’ peripheral blood. The blood samples were taken by means of a venipuncture of a cubital vein that appears full and stored in vacutainers (BD biosciences) of 6ml with Na-EDTA anticoagulant. This was preceded by a written and informed consent by patients to participate in this study. The blood samples were refrigerated for a short period of time on 4°C (not beyond 48 hours) prior to their extraction. This was necessary as to preserve the quality and quantity of the isolated DNA. The DNA samples were stored on a temperature of -20°C until we moved onto the next process step in our analysis. Determining a target DPYD gene structure was done by the Institute for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology in Sarajevo (INGEB) by means of the following methods and procedures: A genotyping methods applied in the study relied on the PCR technology. We have amplified a genotyping-relevant sequence by applying an adequate primer pair subsequent to which we subjected it to an appropriate gene expression profiling (an automatic or a manual fragment analysis). Genomic DNA was extracted from leucocytes with the standard techniques and actual genotyping was done by means of the PCRRFLP. The DPYD exon 14 and its flanking 5’ donor intronic region was amplified with the PCR.

Primers used in the amplification of the exon 14 and its marginal regions (including newly formed Ndel restriction sites) are:

F: 5’ ATC’AGG ACA TTG TGA CAT ATG TTT C 3’

R: 5’ CTT GTT TTA GAT GTT AAA TCA CAC ATA 3’

In our study, we have applied a method of highly specific typisation of the DNA sequence previously replicated during the PCR process. The PCR method followed the above outlined primer sequences as to ensure genotyping of DPYD2A* polymorphisms in the DPYD gene. Relevant PCR products were tested by an agarose gel electrophoresis and then treated with the restriction enzyme Ndel (endonuclease) in an appropriate buffer solution on 37°C. During the RFLP processing, we have incubated 14ml of the PCR products overnight on 37°C with 3U endonuclease Ndel. Restriction fragments were separated by the 3% agarose gel electrophoresis stained with ethidium bromide. The genotyping, i.e. assessment of the size of restriction fragments, was done on a visual basis by identifying the wild-type allele (IVS14+1G) by means of splicing 198 bp with the PCR product to 181 bp and 17 bp fragments. Conversely, a mutant allele produced three fragments subsequent to Ndel digestion: 154 bp, 27, bp and 17 bp. Relevant results were recorded by taking photographs of gels under an UV light.

RESULTS

The human DPD gene (DPYD) is present as a single copy gene on the chromosome 1p22 and consists of 23 exons.

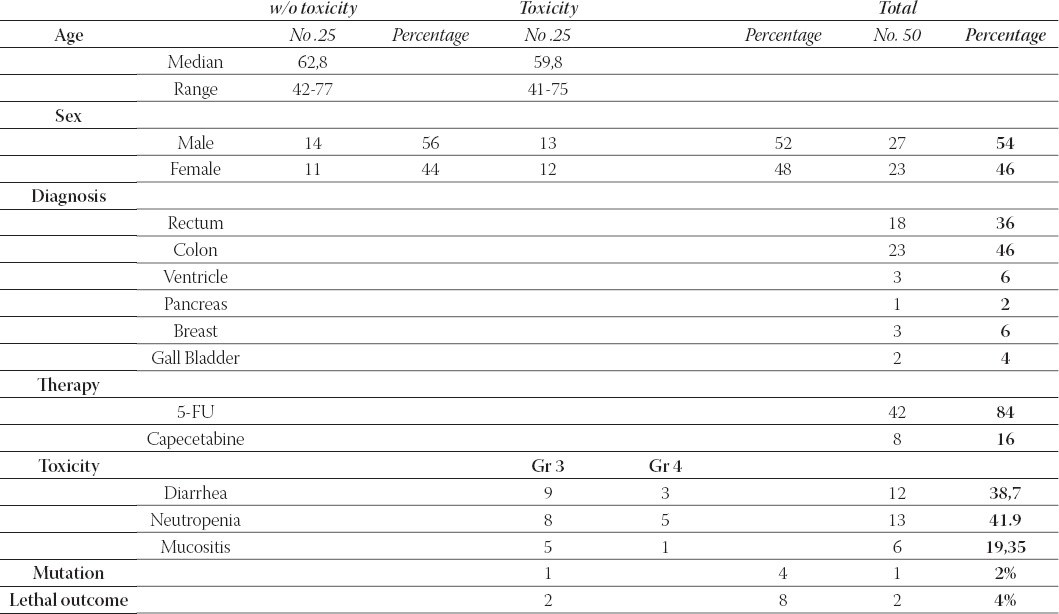

Table 1. provides an overview of aH patients who participated in our study, their respective characteristics and responses to treatments vs. the subject-matter mutation.

TABLE 1.

Overview of patients characteristics

Toxicity and lethal outcome

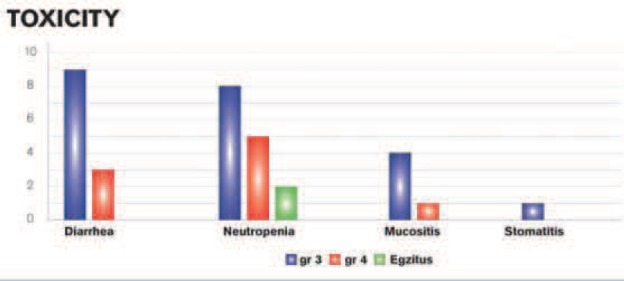

A toxic events analysis was done in accordance with the Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC). We have factored in only those toxic events that could be interpreted by means of either laboratory tests or clinical examinations. There were also other cases like a neurological toxicity, but we have not taken it into consideration as we were unable to draw a clear line between this toxicity and the 5-FU. We have described three types of toxicities exhibited by our patients: diarrhea, neutropenia with a resulting leukopenia and mucositis (to include stomatitis as well) (Chart 1.) Majority of cases, i.e. 13 subjects, had neutropenia, which is nearly 42% of all symptoms, while remaining subjects had diarrhea and mucositis. Not one of these events had a statistical significance over the other two. While the grade 3 mostly involves diarrhea, the grade 4 neutropenia, so it is evident that the only 2 lethal outcomes occurred with patients with the grade 4 neutropenia. This is to say that this occurrence bears a statistical significance of p=0,021505 according to the Fisher’s exact test. During our research, we had two lethal outcome cases that belonged to the group of subjects with toxicity subsequent to the 5-FU treatment. Therein, the significance level p was 0,244897. Both of these cases occurred after the grade 4 neutropenia, so this event bears a statistical significance of p= 0,021505 according to the Fisher’s exact test.

CHART 1.

Overview of toxicity types

IVS14 + 1 G >Λ DPYD*2AMUTATION

Our research has undeniably attested to existence of one heterozygote for the DPYD gene mutation, i.e. one heterozygote for IVS14 + 1 G > A, DPYD*2A mutation.

We have determined existence of the heterozygote for the subject-matter mutation with the patient No. 28 of our test group. This patient was 39 years of age when she was diagnosed with a breast cancer with a liver metastasis as per relevant x-ray and CT scan imaging. After convening a consultation team, it was opted against conducting any surgery due to the stage of the illness. Instead, it was decided to start with a chemotherapy protocol with Capecitabine. Seven days after beginning the Capecitabine treatment, i.e. during the first cycle of treatment, the patient was admitted as an emergency case by our Emergency Department after being administered with a Capecitabine dosage of 1,250 mg / m2 twice a day. Attending physician’s exam and relevant laboratory tests have indicated to leukopenia and neutropenia - grade 4 (L 0,61 109/l), as well as the grade 4 mucositis (oral cavity was covered with white coating and crusts) and the grade % diarrhea (over 10 liquid stools within 24 hours). The patient was prostrated, hypotensive and exhibited signs of hepatic insufficiency. She was then treated with GSF (Neupogen), antibiotics (Amoxicillin, clavulanic acid and Ciprofloxacin), intravenous solutions and other symptomatic therapy. After 4 days, despite all measures of supportive therapy in accordance with the NCNC Guide, the patient fell in a comatose state. In a matter of hours, exitus letalis occurred.

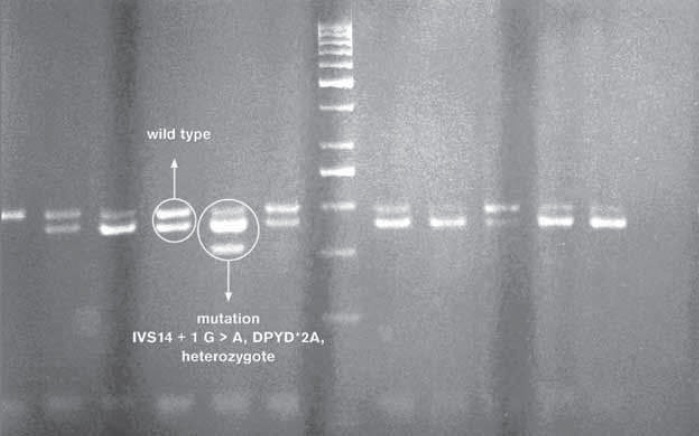

Find below is an UV photograph (Figure 1.) taken after staining the 3% agarose gel with ethidium bromide. The image displays wild-type DPYD in lane 4 and heterozygote mutation in lane 5. The latter is IVS14 + 1 G > A, DPYD*2A that appeared after restriction, while the wild-type allele was identified by splicing 198 bp with a PCR product on 181 bp and 17 bp fragments. Conversely, the mutant allele produced three fragments after Ndel digestion: 154 bp, 27, bp and 17 bp.

FIGURE 1.

DPYD*2A mutation.

DISCUSSION

Although it was synthesised over 40 years ago, the 5-FU remains one of the most prescribed cytostatic agents in treatment of various malignant diseases. Adverse drug reactions still remain one of the most significant clinical problems. This, coupled with the meta-anal- ysis results involving 1,219 patients treated with the 5-FU, indicate that grades 3 and 4 toxicities occur with 31-24% of patients and have a lethality rate of 0,5% (9). Although we are well aware now that many human illnesses are caused by gene mutations, there is a lesser awareness of a fact that known gene variances can affect a patient’s response to certain drugs (10, 11).

The importance of the DPD deficiency and severe 5-FU-related toxicity is of even greater significance considering the wide range of the 5-FU administration. The meta-analysis covering a group of over 1,200 patients suggests that more than 30% of patients treated with the 5-FU experienced a major toxic event prompted by this medication. A frequency of low DPD enzyme activity in the general population was initialy evaluated to be somewhere between 3-5%.

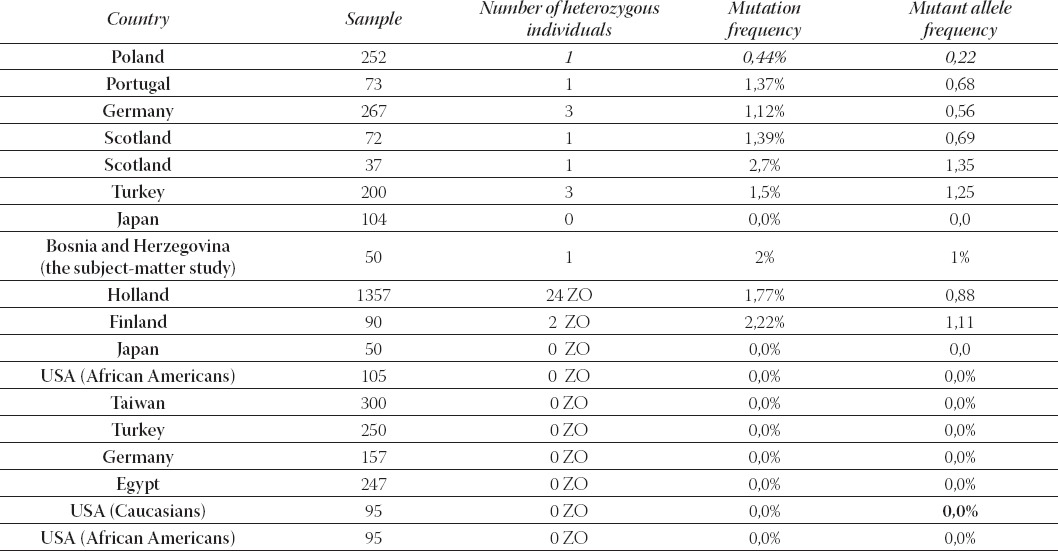

However, further studies have proven a significant variability between different ethnic groups (Table 2). The human DPD gene (DPYD) is present as a single copy gene on the chromosome 1p22 and consists of 23 exons. The Table 2. provides an insight into results of certain studies (ours included) that dealt with determining relevant prevalence rate with patients of different ethnic groups. As we can see, none of the neighboring countries, has had anything published regarding this type of research on patients administered with the 5- fluorouracil, as far as we know. Hence, this makes our study that more important as it practically substantiates the only example of the DPYD 2A mutation in the region. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, more precisely in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, there were 1,303 patients treated with the 5-FU during the Y2008, while in the same period there were 657 patients administered with Capecetabine (source: FB&H Solidarity Insurance Fund). To certain extent, these figures apply to our study as well, as we do not have specific information on the 5-FU-related toxicity. This is to say there is no exact method of monitoring these patients and recording of toxic events, so we can only speculate on the issue at the country level. Given these numbers, i.e. considering that in the Y2008 alone there were altogether 1,960 patients treated with the 5-FU and Capecetabine and considering that our study indicated to 2% mutation frequency, this means that there are over 39,2 patients every year that is prone to a severe toxic response and possibly lethal outcome subsequent to the 5-FU administration. The root cause here is the DPD gene mutation. Another fact to consider is that exon 14-skipping accounts for nearly 50% of the DPD deficiency. Therefore, the aforesaid number of patients would have been much greater even based solely on changes in one gene in the 5-FU metabolism.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of IVS14+1G> A DPYD mutation in persons from different countries (12)

Another interesting information here is that all heterozygous patients with proven mutations in aH mentioned studies, have had the grade 4 neutropenia. If we take the findings of our study and compare it against the grade 4 neutropenia alone (wherein relevant toxicity rate was above 90% for patients with the DPYD 2A* mutation and ended in a lethal outcome) and considering that it indicates that 20% of our test group with the grade 4 neutropenia symptoms had the subject-matter mutation, then our results are very similar with such studies. Of course, we take due note of the earlier mentioned limitations imposed on this research. In conclusion, during our study, the lethal outcome occurred with two patients suffering from the grade 4 neutropenia. It is pertinent to note here that the said mutation (IVS14+1G>A), in any case, does not represent a sole cause of death in patients developing the life-threaten- ing toxicity after the 5-FU administration. So far, the analysed gene displayed over 70 mutations and other metabolic pathways that may have caused the said lethality.

The deficient DPD activity is a pharmacogenetic syndrome with a possible fatal outcome following the 5-FU therapy. Although molecular defects of DPYD leading to the deficient DPD activity can be root causes of the 5-FU syndrome, actual DPD regulatory mechanisms have not been clearly outlined. This calls for highly specific techniques for screening of the entire DPYD gene and for measuring DPD activity. Resultantly, this would enable us to draw clear conclusions of the relationship between the genotype and phenotype of the pharmacogenetic syndrome in question.

Certainly, this is only a speculative statement on our part, as more elaborate and definite conclusions can be reached only after conducting a greater scale of research. Still, it provides us with indicative information.

Even major countries have not yet solved a matter of routine screening of patients, but there is an increasing tendency of such tests. This is rooted in a pharmaco-eco- nomic aspect as treatment costs for patients experiencing severe toxicity have already proven to be much greater than screening costs. Needless to say, new screening methods are reducing inherent costs even further down.

CONCLUSION

Our study has indicated to the presence of the DPD mutation on the exon 14 (IVS14+1G>A). This is the first time such a case was reported with respect to the Bosnian population. (DPYD*2A frequency is nearly 2%).

Furthermore, we attest to IVS14+1G>A DPYD mutation being responsible for a significant proportion of the life-threat- ening toxicity in the 5-FU administration. This is based on a sample of four patients suffering from the CTC-defined grade 4 myelosupression after being treated with the 5-FU.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1998;15:1200–1205. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maring JG, van Kuilenburg AB, Haasjes H, Piersma H, Groen JM, Uges DR, De Vries EG. Reduced 5-FU clearance in a patient with low DPD activity due to heterozygosity for a mutant allele of the DPYD gene. Br. J. Cancer. 2002;86:1028–1033. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Kuilenburg AB, Haasjes J, Richel DJ, et al. Clinical impications of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency in patients with severe 5 FU associated toxicity: identification of new mutations in the DPD gene. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(12):4705–4712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson MR, Diasio RB. Importance of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency in patients exhibiting toxicity following treatment with 5-flourouracil. Adv. Enz. Regul. 2001;41:151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(00)00011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Kuilenburg ABP, De Abreu RA, van Gennip A.H. Pharmacogenetic and clinical aspects of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2003;40(1):41–45. doi: 10.1258/000456303321016150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mc Leod HL, Collie-Duguid ES, Vreken P, et al. Nomenclature for human DPYD alleles. Pharmacogenetics. 1998;8:455–459. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199812000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Kuilenburg ABP, Vreken P, Abeling NG, Bakker HD, Meinsma R, Van Lenthe H, et al. Genotype and phenotype in patients with dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency. Hum. Genet. 1999;104:1–9. doi: 10.1007/pl00008711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Kuilenburg ABP, Vreken P, Abeling NGGM, Bakker HD, Meinsma R, Van Lenthe H, et al. Genotype and phenotype in patients with dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency. Hum Genet. 1999;104:1–9. doi: 10.1007/pl00008711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meta-Analysis Group in Cancer: Toxicity of fluorouracil in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: effect of administration schedule and prognostic factors. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998;16(11):3537–3541. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.11.3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haga SB, Burke W. Using pharmacogenetics to improve drug safety and efficacy. JAMA. 2004;291(23):2869–2871. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein DB, Tate SK, Sisodiya SM. Pharmacogenetics goes genomic. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003;4:937–947. doi: 10.1038/nrg1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sulzyc-Bielicka V, Biñczak-Kuleta A, Pioch W, Kadny J, Gziut K, Bielicki D, Ciechanowicz A. 5-Fluorouracil toxicity-attributable IVS14 +1G >A mutation of the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene in Polish colorectal cancer patients. Pharmacol. Rep. 2008;60:238–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]