Abstract

To determine whether coping strategies modify the risk of depression among allogeneic recipients experiencing post-transplant-related symptomatology, 105 participants (mean age = 52 years, 42% female) completed questionnaires 90 days post-transplant. A total of 28 percent reported depressive symptoms. Univariate correlations indicated that depression was associated with greater transplant-related symptomatology and avoidance, acceptance/resignation, and emotional discharge coping. Depression was negatively associated with problem-solving coping. Moderator analyses indicated that transplant-related symptomatology was significantly associated with depression among patients who frequently used maladaptive coping and rarely used adaptive coping. These data suggest that transplant-related symptomatology, combined with maladaptive coping, place patients at risk of depression.

Keywords: cancer, coping, depression, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, oncology

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) improves long-term survival rates among patients diagnosed with malignant hematologic diseases (Pasquini and Wang, 2011). Allogeneic HCT is increasingly performed worldwide, resulting in a large number of survivors for whom HCT-related morbidities are an important outcome. Morbidities among HCT recipients are common due to high-dose chemotherapy, opportunistic infections, and acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Morbidities can affect multiple organs and be life-threatening; the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and auditory or visual systems are particularly vulnerable (Sun et al., 2013). Consequently, patients often report a high degree of HCT-related symptomatology which is associated with reduced quality of life (Bevans et al., 2008; Cohen et al., 2012) and worse mental health (Bevans et al., 2008). For example, 12–29 percent of HCT recipients report posttraumatic stress disorder (El-Jawahri et al., 2015b; Hefner et al., 2014), 13–20 percent anxiety (El-Jawahri et al., 2015a; Pillay et al., 2015), and 6–44 percent depression (Artherholt et al., 2014; El-Jawahri et al., 2015a, 2015b; Pillay et al., 2015).

Depression is a cause for concern among HCT recipients due to its association with adverse health outcomes. For example, pre-transplant depression prospectively predicted slower white blood cell recovery in the first 3 weeks after transplant (McGregor et al., 2012), while post-transplant depression has been found to be associated with non-adherence to treatment (Mumby et al., 2011), increased hospital length of stay (Prieto et al., 2002), and greater mortality (Loberiza et al., 2002; Prieto et al., 2002). Moreover, HCT recipients with depression are 13 times more likely to report suicidal ideation as recipients without depression (Sun et al., 2013).

An important question is the extent to which risk of depression is modifiable among HCT recipients, such as through adaptive patient coping. Coping can be defined as dynamic cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage stress (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). Coping strategies can be broadly conceptualized as adaptive (e.g. engaging with the problem in a constructive manner) or maladaptive (e.g. evading the problem or blaming others) (Moos, 1993; Wenzel et al., 2002). To our knowledge, only three studies have examined coping and depression in HCT recipients. They suggest that prior to HCT, problem solving was associated with less depression, while acceptance/resignation and avoidant coping were associated with greater depression (Fife et al., 2000; Rodrigue et al., 1993; Wells et al., 2009). However, coping was not associated with depression at 2 weeks or at 6-months post-HCT (Fife et al., 2000; Wells et al., 2009). All three studies included both allogeneic and autologous HCT recipients; thus, differences in recovery post-HCT based on transplant type (e.g. GVHD) may have obscured relationships between coping and depression. In summary, existing data suggest that HCT recipients who cope with maladaptive coping strategies rather than adaptive coping strategies may be at higher risk for depression; however, the degree to which these relationships persist beyond the pre-HCT period remains to be clarified.

The goal of this study was to examine the relationship between HCT-related symptomatology, coping, and depression in a sample of allogeneic HCT recipients. Moreover, we sought to examine the extent to which coping modifies risk of depression associated with HCT-related symptom severity. Significant results would suggest that depression risk may be mutable among patients experiencing HCT-related symptoms, perhaps via intervention to improve coping skills. We hypothesized that (1) severity of HCT-related symptomatology would be significantly associated with depression, (2) adaptive coping strategies would be associated with less depression and maladaptive coping would be associated with more depression, and (3) risk of depression associated with HCT-related symptom severity would be greatest in patients who exhibited poor coping.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited as part of a larger study of quality of life in allogeneic HCT recipients. Eligible patients were at least 18 years old, were diagnosed with hematologic cancer, were scheduled to receive allogeneic HCT with peripheral blood stem cells at Moffitt Cancer Center, had no history of cerebrovascular accident or head trauma with loss of consciousness, had completed 6 or more years of formal education, were able to speak and read standard English, and signed the written informed consent. The study was approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board.

Procedures

Potential participants were identified using clinical information systems in consultation with the attending physician. Participants were approached at an outpatient visit approximately 1 month prior to transplant. Eligible patients who wished to participate signed informed consent prior to participation and completed baseline demographic information at this time. Participants were contacted again 90 days after transplant to complete follow-up questionnaires regarding HCT-related symptomatology, depression, and coping. Participants for the current analyses were recruited between December 2010 and January 2013. At the time the analyses were conducted, 217 patients were approached, 34 refused (e.g. not interested, overwhelmed or no reason given), 183 signed consent, and 105 had data at baseline and 90 days post-HCT.

Measures

Demographic and clinical data

Self-reported sociodemographic characteristics were assessed prior to transplant (i.e. age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, education, and annual household income). A medical record review was performed at study entry in order to obtain clinical information (i.e. cancer type and date of HCT).

HCT-related symptomatology

The 30-item HCT Symptom Scale (Lee et al., 2002) assesses self-reported severity of HCT symptomatology across multiple organ systems in the previous month. Items are evaluated on a five-point Likert scale, (0 = not at all, 4 = extremely), with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. The scale yields a total score and subscales for seven categories of symptomatology: skin, eyes and mouth, lung, digestive, muscles and joints, energy, and psychological symptoms. A modified version of the total summary score was used in the current analyses; this version did not include the psychological symptoms subscale to avoid inflated relationships with coping and depression. The scale has excellent reliability and validity (Lee et al., 2002).

Coping

Coping was assessed using the 48-item Coping Response Inventory (CRI) (Moos, 1993). Items are assessed on a four-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 3 = fairly often). The scale yields eight subscales: Logical Analysis, Positive Reappraisal, Seeking Guidance, Problem Solving, Cognitive Avoidance, Acceptance/Resignation, Seeking Alternative Rewards, and Emotional Discharge. Subscale scores range from 0 to 18 with higher scores indicating more frequent use of the strategy. The CRI has demonstrated reliability and validity (Moos, 1993) and has previously been used in HCT recipients (Jacobsen et al., 2002; Wells et al., 2009).

Depression

Depression was assessed using the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). Items assess the frequency of depressive symptoms in the past week according to a four-point scale (0 = rarely or none of the time, 3 = most or all of the time). A total score is obtained by summing item responses. Scores range from 0 to 60 with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptomatology. A score of 16 or higher indicates clinically significant depressive symptomatology (Radloff, 1977). The CES-D is commonly used for assessing depression in patients with cancer due to the absence of items related to cancer-related physical symptoms that could overlap with depression (e.g. weight loss, appetite, fatigue, and health concerns) (Andrykowski, 1994). The CES-D has high internal consistency (Radloff, 1977) and validity in cancer populations (Hann et al., 1999).

Statistical analyses

Means and frequencies were calculated to describe sample sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Spearman's correlations were performed to assess the magnitude of univariate relationships among depression, HCT-related symptomatology, and coping strategies. Linear regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between HCT-related symptomatology and depressive symptomatology. Because younger age and female gender have been found to be risk factors for depression in HCT recipients (Kuehner, 2003), these variables were identified a priori as covariates to be included in multivariate analyses. Analyses examining coping strategies as moderators of the relationship between HCT-related symptomatology and depression were conducted using bootstrapping (Hayes and Matthes, 2009). Interactions significant at p < .05 were decomposed using the Johnson–Neyman technique to plot changes in beta weights regressing depression on HCT-related symptomatology at various levels of the coping strategy examined.

Results

A total of 105 participants contributed data to the current analyses. Sample demographic and clinical descriptives are reported in Table 1. At 90 days post-HCT, 30 (28%) patients met criteria for clinically significant depressive symptoms. Self-reported HCT symptomatology at this time was widespread. A total of 88 (83%) patients reported symptoms of the skin, 73 (71%) eye or mouth symptoms, 65 (62%) pulmonary symptoms, 43 (41%) digestive symptoms, 86 (82%) muscle and joint symptoms, and 91 (87%) reported reduced energy.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample (n = 105).

| Age: mean, SD | 51.85 | 12.90 |

| Gender: n, % female | 44 | 42 |

| Ethnicity: n, % non-Hispanic | 98 | 93 |

| Race: n, % Caucasian | 90 | 86 |

| Marital status: n, % married | 70 | 67 |

| Education: n, % college | 44 | 42 |

| graduate | ||

| Annual household income: n, % US$ 40,000 or greater | 56 | 53 |

| Diagnosis: n, % | ||

| AML | 32 | 30 |

| MDS | 20 | 19 |

| NHL | 17 | 16 |

| ALL | 13 | 12 |

| CLL | 8 | 8 |

| CML | 7 | 7 |

| MM | 4 | 4 |

| MPD | 2 | 2 |

| Other leukemia | 2 | 2 |

| Mean (SD) CES-D score | 12.03 | 8.70 |

| Mean (SD) HCT Symptom | 15.40 | 10.89 |

| Scale scorea | ||

ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML: acute myelogenous leukemia; CES-D: Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale CLL: chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML: chronic myelogenous leukemia; MDS: myelodysplastic syndrome; MM: multiple myeloma; MPD: myeloproliferative syndrome; NHL: non-Hodgkin lymphoma; SD: standard deviation;.

HCT Symptom Scale score calculated as a mean of all subscales except mental distress.

Frequency of coping strategy use and correlations between coping, HCT-related symptomatology, and depression are shown in Table 2. Problem-solving coping was associated with significantly less depressive symptomatology (p = .04), while avoidance, acceptance/resignation, and emotional discharge were associated with greater depressive symptomatology (p values < .002). HCT-related symptomatology was not associated with any coping strategy (ps > .13) but was significantly associated with depressive symptomatology (p < .0001). The relationship between HCT-related symptomatology and depressive symptomatology remained significant in regression analyses controlling for age and gender (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Frequency of use of coping strategies and correlations with HCT-related symptomatology and depression.

| Coping strategy | Definition (Moos, 1993) | Any use, n (%) | Use “sometimes” or “fairly often,” n (%) | Correlation: HCT-related symptomatology, r | Correlation: depression, r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logical analysis | Cognitive attempts to prepare mentally for a stressor | 102 (97) | 26 (25) | 0.09 | 0.11 |

| Positive reappraisal | Cognitive attempts to construe and restructure a problem in a positive way while accepting the reality | 103 (98) | 63 (60) | 0.00 | −0.05 |

| Seeking guidance and support | Behavioral attempts to seek information, guidance, and support | 103 (98) | 35 (33) | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Problem solving | Behavioral attempts to take action to deal directly with the problem | 104 (99) | 54 (51) | −0.13 | −.20* |

| Cognitive avoidance | Cognitive attempts to avoid thinking realistically | 99 (94) | 14 (13) | 0.08 | 0.37** |

| Acceptance/resignation | Cognitive attempts to react to the problem by resigning oneself to it | 99 (94) | 14 (13) | 0.15 | 0.31** |

| Seeking alternative rewards | Behavioral attempts to get involved in substitute activities and create new sources of satisfaction | 100 (95) | 12 (11) | −0.03 | −.11 |

| Emotional discharge | Behavioral attempts to reduce tension by expressing negative feelings | 92 (88) | 1 (1) | 0.13 | 0.32** |

p < .05;

p < .01.

Table 3.

Linear regression analyses examining the effects of HCT-related symptomatology on depressive symptomatology controlling for age and gender.

| Statistics by predictor | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| b | t | |

| Age | −0.26 | −3.22** |

| Gender (female) | −0.01 | −0.12 |

| HCT-related symptomatology | 0.51 | 6.25** |

p < .01.

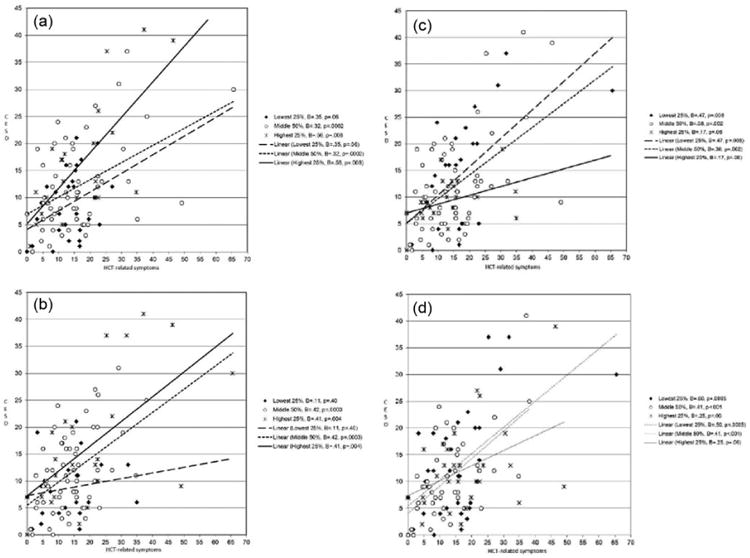

Moderation analyses indicated that coping significantly modified the risk of depression associated with HCT-related symptomatology (see Table 4). Specifically, the relationship between HCT-related symptomatology and depression was stronger among patients who frequently used maladaptative coping strategies (i.e. cognitive avoidance and emotional discharge) and rarely used adaptive coping strategies (i.e. positive reappraisal and problem solving) (p values < .05). The relationship between HCT-related symptomatology and depression was not modified by patients' use of logical analysis, seeking guidance and support, acceptance or resignation, or seeking alternative rewards (p values > .11). Figure 1 shows the risk of depression associated with HCT-related symptomatology according to the use of the four coping strategies found significant in the moderation analyses.

Table 4.

Results of analyses examining coping strategies as moderators of the relationship between HCT-related symptomatology and depression.

| Statistics by predictor | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| b | t | |

| Moderator: logical analysis | ||

| Age | −0.18 | −3.39** |

| Gender (female) | −0.65 | −0.45 |

| HCT-related symptomatology | 0.62 | 4.18*** |

| Logical analysis | 0.47 | 1.55 |

| Interaction HCT-related symptomatology × logical analysis | −0.02 | −1.61 |

| Moderator: positive reappraisal | ||

| Age | −0.19 | −3.29** |

| Gender (female) | −0.52 | −0.36 |

| HCT-related symptomatology | 0.74 | 4.25*** |

| Positive reappraisal | 0.45 | 1.53 |

| Interaction HCT-related symptomatology × positive reappraisal | −0.03 | −2.06* |

| Moderator: seeking guidance | ||

| Age | −0.18 | −3.34** |

| Gender (female) | −0.43 | −0.29 |

| HCT-related symptomatology | 0.52 | 4.23*** |

| Seeking guidance and support | 0.26 | 0.84 |

| Interaction HCT-related symptomatology × seeking guidance and support | −0.01 | −1.13 |

| Moderator: problem solving | ||

| Age | −0.16 | −2.92** |

| Gender (female) | −0.13 | −0.09 |

| HCT-related symptomatology | 0.87 | 3.84*** |

| Problem solving | 0.27 | 0.79 |

| Interaction HCT-related symptomatology × problem solving | −0.04 | −2.18* |

| Moderator: cognitive avoidance | ||

| Age | −0.12 | −2.34* |

| Gender (female) | −0.95 | −0.72 |

| HCT-related symptomatology | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| Cognitive avoidance | −0.01 | −0.03 |

| Interaction HCT-related symptomatology × cognitive avoidance | 0.04 | 2.62* |

| Moderator: acceptance or resignation | ||

| Age | −0.16 | −2.91** |

| Gender (female) | −0.17 | −0.12 |

| HCT-related symptomatology | 0.39 | 2.28* |

| Acceptance or resignation | 0.38 | 1.23 |

| Interaction HCT-related symptomatology × acceptance or resignation | −0.01 | −0.06 |

| Moderator: seeking alternative rewards | ||

| Age | −0.17 | −3.01** |

| Gender (female) | 0.37 | 0.25 |

| HCT-related symptomatology | 0.37 | 3.27** |

| Seeking alternative rewards | −0.33 | −0.99 |

| Interaction HCT-related symptomatology × seeking alternative rewards | <0.01 | 0.35 |

| Moderator: emotional discharge | ||

| Age | −0.13 | −2.42* |

| Gender (female) | −1.04 | −0.76 |

| HCT-related symptomatology | 0.13 | 1.05 |

| Emotional discharge | 0.09 | 0.19 |

| Interaction HCT-related symptomatology × emotional discharge | 0.04 | 2.08* |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Associations between HCT-related symptomatology and depression at high, medium, and low levels of coping: (a) avoidance, (b) emotional discharge, (c) problem solving, and (d) positive reappraisal. As a guide to interpretation, relationships between HCT-related symptomatology and depression are shown for the 25 percent of the sample reporting the greatest use of the coping strategy (solid line, Xs), the 50 percent of the sample reporting moderate use of the symptom (short dashed line, Os), and the 25 percent of the sample reporting the least use of the coping strategy (long dashed line, diamonds). Beta weights and p values for the relationship between HCT-related symptomatology and depression within each group are provided in the legends.

Conclusion

This study examined relationships among self-reported HCT symptomatology, depressive symptoms, and coping strategies in hematologic cancer patients treated with allogeneic HCT. Hypotheses were largely confirmed. Greater depressive symptomatology was associated with greater HCT-related symptomatology, less use of use of problem-solving coping, and greater use of avoidance, acceptance/resignation, and emotional discharge coping. Coping moderated the risk of depression associated with HCT-related symptomatology such that patients with greater HCT-related symptomatology who used more maladaptive coping strategies (i.e. cognitive avoidance and emotional discharge) and less adaptive strategies (i.e. reappraisal and problem solving) were more likely to be depressed.

The significant relationship between HCT-related symptomatology and depressive symptomatology observed in this study is consistent with previous literature reporting that severity of HCT-related symptoms is a risk factor for depression (Lee et al., 2006; Mosher et al., 2011; Pidala et al., 2011; Syrjala et al., 2004). We observed significant relationships among post-HCT coping and depression, which has not been reported in previous studies (Rodrigue et al., 1993; Wells et al., 2009). In contrast to previous studies which analyzed data from mixed samples of autologous and allogeneic HCT recipients, this study focused exclusively on allogeneic HCT recipients. Greater homogeneity of our sample regarding treatment type may have enabled us to detect a signal that other studies missed. Interestingly, coping was not associated with HCT-related symptomatology, suggesting that patients do not cope with HCT-related symptoms in a consistent manner. This study adds significant new knowledge regarding coping as a moderator of the risk of depression associated with HCT-related symptomatology. Specifically, HCT recipients with good coping skills demonstrate psychological resilience even when experiencing greater HCT-related symptoms.

This study is characterized by several strengths, including a focus on allogeneic HCT recipients who face significant challenges post-transplant but for whom little about their coping is known. The study also used validated measures of coping, depression, and self-reported HCT-related symptomatology. In addition, participants were assessed at a uniform time since transplant when many were experiencing HCT-related morbidities. Nevertheless, study limitations should also be noted. The cross-sectional design of the study does not allow for determination of directionality of findings. For example, it may be that depression alters patients' coping repertoire such that they cope less adaptively after onset of depression. However, studies in other cancer populations have demonstrated that maladaptive coping strategies often precede depressive symptoms (Hack and Degner, 2004; Kraemer et al., 2011). In addition, the study was performed at a single site in the United States and included a sample of mainly white, Caucasian, married, and well-educated participants. Both of these factors may limit the generalizability of findings.

In conclusion, results highlight the fact that patients with poor coping skills are more vulnerable to depression when faced with HCT-related symptomatology. These patients may benefit from proactive clinical care to reduce or prevent depression when experiencing HCT-related symptoms, such as antidepressant medication or referral to a mental health professional. Future studies should examine whether interventions to improve coping skills reduce risk of depression among patients who cope poorly with HCT-related symptoms. Previous research in breast cancer patients has demonstrated benefits of group psychological interventions aimed at helping patients cope with their illness and treatment side effects (Andersen et al., 2004, 2008; Antoni, 2013; Antoni et al., 2006; Carver et al., 2005). These benefits include decreased symptoms of depression and anxiety, less intrusive thoughts, less social disruption, greater positive emotions, and better quality of life. Moreover, benefits persisted up to 13 years after treatment (Carver et al., 2005). Only two studies have aimed to adapt such interventions to the unique needs of HCT survivors. DuHamel et al. (2010) developed a 10-week telephone-delivered psychological intervention to address posttraumatic stress and social support in patients who were 1 to 3 years post-HCT (DuHamel et al., 2010). Participants receiving this intervention reported significant improvement in posttraumatic stress symptoms, distress, and depression relative to controls (DuHamel et al., 2010). Syrjala et al. (2011) reported on the development of an Internet-delivered intervention to address survivorship care needs in HCT survivors who were 3 to 18 years post-HCT; a large clinical trial is currently underway (Syrjala et al., 2011). Therefore, additional studies are needed to adapt psychosocial interventions for HCT recipients. Such studies have the potential to significantly improve patient outcomes after HCT.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the Moffitt Survey Methods Core for their assistance with data management.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was supported by NCI K07 CA138499, P30 CA076292, and the Red Temática de Investigación Cooperativa en Cáncer (RTICC).

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz DM, et al. Psychological, behavioral, and immune changes after a psychological intervention: A clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:3570–3580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen BL, Yang HC, Farrar WB, et al. Psychologic intervention improves survival for breast cancer patients. Cancer. 2008;113:3450–3458. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrykowski M. Psychosocial factors in bone marrow transplantation: A review and recommendations for research. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1994;13:357–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH. Psychosocial intervention effects on adaptation, disease course and biobehavioral processes in cancer. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2013;30:S88–S98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, Wimberly S, Lechner S, et al. Reduction of cancer-specific thought intrusions and anxiety symptoms with a stress management intervention among women undergoing treatment for breast cancer. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1791–1797. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artherholt SB, Hong F, Berry DL, et al. Risk factors for depression in patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biology of Blood Marrow Transplantation. 2014;20:946–950. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevans MF, Mitchell SA, Marden S. The symptom experience in the first 100 days following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) Support Care in Cancer. 2008;16:1243–1254. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0420-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Smith RG, Antoni MH, et al. Optimistic personality and psychosocial well-being during treatment predict psychosocial well-being among long-term survivors of breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2005;24:508. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.5.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MZ, Rozmus CL, Mendoza TR, et al. Symptoms and quality of life in diverse patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2012;44:168–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuHamel KN, Mosher CE, Winkel G, et al. Randomized clinical trial of telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce post-traumatic stress disorder and distress symptoms after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:3754–3761. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Jawahri AR, Traeger LN, Kuzmuk K, et al. Quality of life and mood of patients and family caregivers during hospitalization for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2015a;121:951–959. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Jawahri AR, Vandusen HB, Traeger LN, et al. Quality of life and mood predict post-traumatic stress disorder after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2015b;122:806–812. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fife BL, Huster GA, Cornetta KG, et al. Longitudinal study of adaptation to the stress of bone marrow transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2000;18:1539–1549. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.7.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack TF, Degner LF. Coping responses following breast cancer diagnosis predict psychological adjustment three years later. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13:235–247. doi: 10.1002/pon.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann D, Winter K, Jacobsen P. Measurement of depressive symptoms in cancer patients: Evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1999;46:437–443. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Matthes J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41:924–936. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.3.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefner J, Kapp M, Drebinger K, et al. High prevalence of distress in patients after allogeneic hematopoietic SCT: Fear of progression is associated with a younger age. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2014;49:581–584. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen PB, Sadler IJ, Booth-Jones M, et al. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology following bone marrow transplantation for cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:235. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer LM, Stanton AL, Meyerowitz BE, et al. A longitudinal examination of couples' coping strategies as predictors of adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:963. doi: 10.1037/a0025551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehner C. Gender differences in unipolar depression: An update of epidemiological findings and possible explanations. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2003;108:163–174. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Kim HT, Ho VT, et al. Quality of life associated with acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2006;38:305–310. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SK, Cook EF, Soiffer R, et al. Development and validation of a scale to measure symptoms of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biology of Blood Marrow Transplantation. 2002;8:444–452. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12234170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loberiza FR, Rizzo JD, Bredeson CN, et al. Association of depressive syndrome and early deaths among patients after stem-cell transplantation for malignant diseases. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:2118–2126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor BA, Syrjala KL, Dolan ED, et al. The effect of pre-transplant distress on immune reconstitution among adult autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation patients. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2012;30(Suppl):142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. Coping Responses Inventory: Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Lutz, FL: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mosher CE, DuHamel KN, Rini C, et al. Quality of life concerns and depression among hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors. Support Care in Cancer. 2011;19:1357–1365. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0958-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumby P, Hurley C, Samsi M, et al. Predictors of non-compliance in autologous hematopoietic SCT patients undergoing out-patient transplants. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2011;47:556–561. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquini M, Wang Z. Current use and outcome of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: CIBMTR Summary Slides, 2010. 2011 www.cibmtr.org.

- Pidala J, Kurland B, Chai X, et al. Patient-reported quality of life is associated with severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease as measured by NIH criteria: Report on baseline data from the Chronic GVHD Consortium. Blood. 2011;117:4651–4657. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-319509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillay B, Lee SJ, Katona L, et al. A prospective study of the relationship between sense of coherence, depression, anxiety, and quality of life of haematopoietic stem cell transplant patients over time. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24:220–227. doi: 10.1002/pon.3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto JM, Blanch J, Atala J, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and impact on hospital length of stay among hematologic cancer patients receiving stem-cell transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:1907–1917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue JR, Boggs SR, Weiner RS, et al. Mood, coping style, and personality functioning among adult bone marrow transplant candidates. Psychosomatics. 1993;34:159–165. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(93)71907-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun CL, Kersey JH, Francisco L, et al. Burden of morbidity in 10+ year survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation: Report from the bone marrow transplantation survivor study. Biology of Blood Marrow Transplantation. 2013;19:1073–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syrjala KL, Langer SL, Abrams JR, et al. Recovery and long-term function after hematopoietic cell transplantation for leukemia or lymphoma. JAMA. 2004;291:2335–2343. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syrjala KL, Stover AC, Yi JC, et al. Development and implementation of an Internet-based survivorship care program for cancer survivors treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2011;5:292–304. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0182-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KJ, Booth-Jones M, Jacobsen PB. Do coping and social support predict depression and anxiety in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation? Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2009;27:297–315. doi: 10.1080/07347330902978947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel L, Glanz K, Lerman C. Stress, coping, and health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 3rd. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 210–239. [Google Scholar]