Abstract

Purpose

Rural areas persistently face a shortage of mental health specialists. Task shifting, or task sharing, is an approach in global mental health that may help address unmet mental health needs in rural and other low resource areas. This review focuses on task shifting approaches and highlights future directions for research in this area.

Methods

Systematic review on task sharing of mental health care in rural areas of high income countries included: 1) PubMed, 2) grey literature for innovations not yet published in peer-reviewed journals, and 3) outreach to experts for additional articles. We included English language articles published before August 31, 2013, on interventions sharing mental health care tasks across a team in rural settings. We excluded literature: 1) from low and middle-income countries, 2) involving direct transfer of care to another provider, 3) describing clinical guidelines and shared decision-making tools.

Findings

The review identified approaches to task sharing focused mainly on community health workers (CHWs) and primary care providers. Technology was identified as a way to leverage mental health specialists to support care across settings both within primary care and out in the community. The review also highlighted how provider education, supervision, and partnerships with local communities can support task sharing. Challenges, such as confidentiality, are often not addressed in the literature.

Conclusions

Approaches to task sharing may improve reach and effectiveness of mental health care in rural and other low resource settings, though important questions remain. We recommend promising research directions to address these questions.

Keywords: health services research, labor economics, mental health, task sharing, task shifting

Rural areas face a persistent shortage of mental health specialists such as psychiatrists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, psychologists, social workers, and counselors. Rural counties make up two-thirds of all counties and about 20% of the US population,1 but fewer than 10% of the mental health workforce practices are in these settings.2 Mental health specialists in rural areas are often the only mental health professional in their community with little access to colleagues in what is often challenging work.3 Given workforce shortages, individuals in rural, frontier, remote, or isolated settings may rely on a de facto system of care involving the general medical sector, and their friends, family and spiritual leaders.4,5

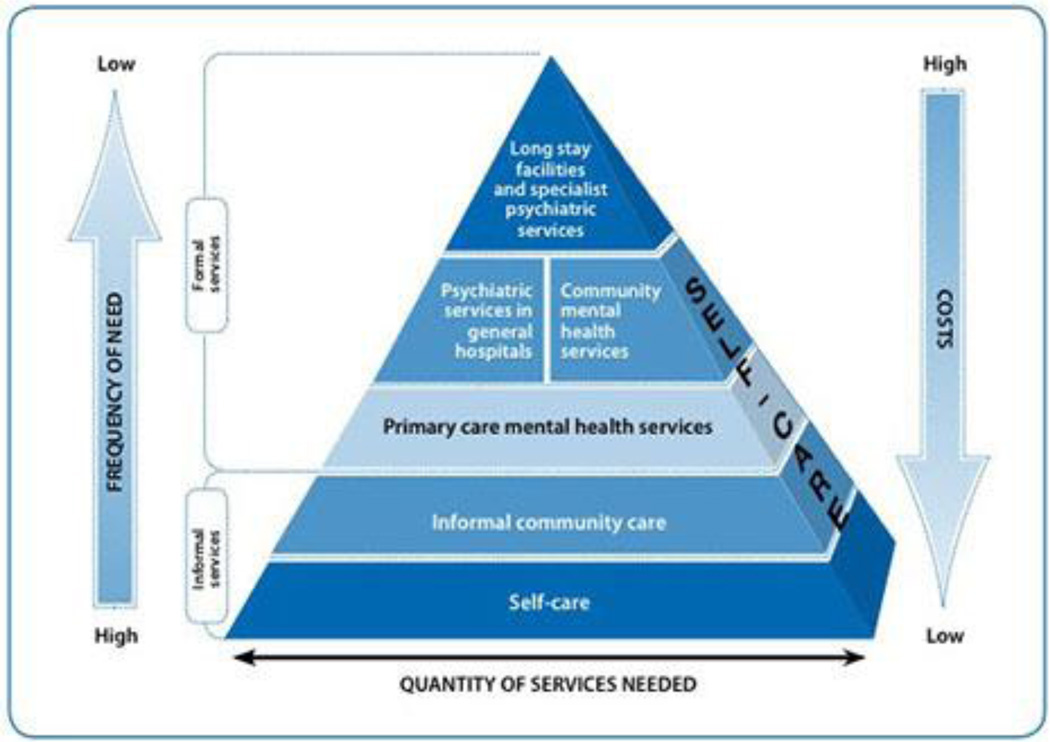

Task shifting, an approach increasingly emphasized in global mental health care, holds promise for improving mental health care delivery. Task shifting entails the shifting of tasks, typically from more to less highly trained individuals to make efficient use of these resources, allowing all providers to work at the top of their scope of practice.6 The World Health Organization conceptualized a service organization pyramid that helps illustrate this shifting of tasks and supply of providers involved in care (see Figure 1).7 Originally popularized in global HIV/AIDS work,6 task shifting has the potential to improve mental health care in rural or otherwise underserved settings in low and high income countries.8,9 The term “task sharing” has been used more recently to describe this concept9 as it more accurately describes that care must be shared within a team of providers. We conceptualize task sharing not as a referral to other providers (eg, to an urban mental health specialist without involving a local provider) but instead a sharing of care among rural providers or between rural and urban providers. For example, teams may include a psychiatric consultant and care manager who engages the patients while following up on depression symptoms such as in a collaborative care model10 and/or include a community health worker (CHW) to increase access to care. Task sharing allows a limited number of specialists to practice in teams with other providers and community resources to reach populations in need. The mental health specialist role shifts from direct service provider toward trainer, supervisor, and consultant. Task shifting was first discussed as a solution to scaling up mental health9,11 through programs in India, Uganda and Pakistan.12–16 The MANAS trial in India, for example, involved lay health workers supervised by a mental health specialist and medication management by a primary care physician to treat depression and anxiety.16

Figure 1.

WHO Service Organization Pyramid for Optimal Mix of Services for Mental Health

Source: The optimal mix of services for mental health. Geneva: World Health Organization 2007

We examined the literature on task sharing of mental health services in rural areas of the US and other high income countries. This review developed from a literature review conducted for the Office of Rural Mental Health Research at the National Institute of Mental Health which included questions on what is known about task shifting in rural mental health care in the US; what can be learned from global settings on this topic; and recommendations for future research. We learned through this review that what is known in low and middle income settings may not apply to high income countries given differences in infrastructure across these settings.17 We thus limit this review to literature from high income countries based on classifications from the World Bank. We view rural areas in the US as a low resource setting and feel findings from this review will generalize to other low resource settings in the US. The objectives of this paper are to: 1) learn from task shifting approaches to mental health care delivery in rural areas of high income countries to offer insights on promising approaches to task sharing mental health care among a team of providers in low resource settings of the US, and 2) highlight the research needed to further develop task sharing for mental health care delivery in low resource settings in the US.

Methods

We conducted a review of peer-reviewed and grey literature to determine where task sharing of rural mental health care delivery was occurring in high income countries. Grey literature encompasses papers, reports, and PowerPoint slides that are posted online but not within the peer-reviewed literature. We also consulted with 10 experts in areas of task shifting, mental health, and health disparities to broaden search terms and recommend articles for the review. We searched PubMed, focusing on the intersection of the task shifting literature and rural mental health literature. Task shifting search terms included task shifting, task sharing, task substitution, non-physician, physician extender, community health worker, community behavioral health worker, lay health worker, lay counselor, promotora, promotores, peer, patient navigator, community-based facilitator, non-professional, non-specialist, traditional healer, church, community-based organization, integrated care, shared care, telehealth, telemedicine, telepsychiatry, self-care, self-management, health manpower, staff development, and patient care teams. Promotoras are a type of CHW that work within predominantly Hispanic communities. Rural mental health search terms included: 1) rural health services and rural populations and 2) mental health services, community mental health centers, and community mental health services. The search was limited to English language literature prior to August 31, 2013. Articles were excluded if they focused solely on 1) transferring specialty mental health care from urban to rural settings via telehealth or 2) clinical guidelines or shared decision-making tools. We included telehealth programs focused on consultation to rural primary care providers. As the review focused on mental health care in the US, we included only literature from high income countries. To complement the PubMed search, the grey literature review included the Google search engine, dissertation abstracts in ProQuest, and conference abstracts in the National Library of Medicine (NLM) Gateway for terms related to mental health, task shifting, promotora, or CHWs. The protocol for this review is available upon request from the first author.

Results

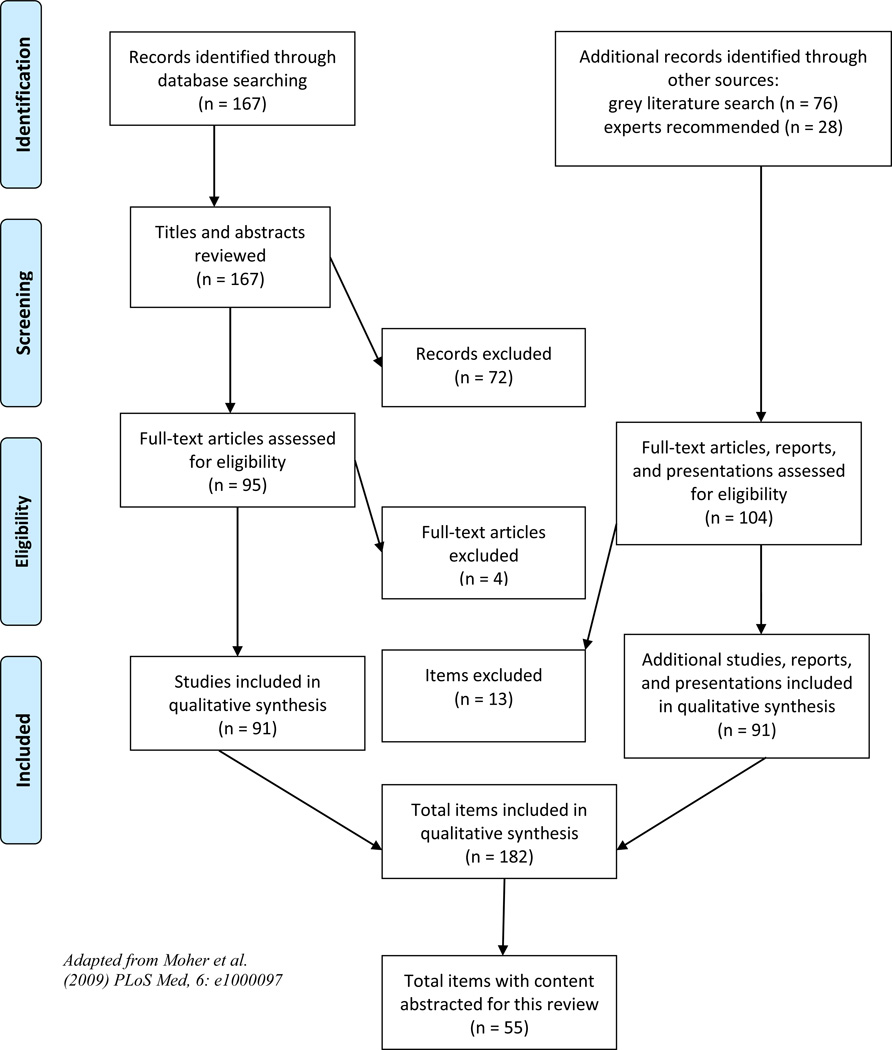

We located 271 articles, reports, and presentations from the peer-reviewed and grey literature, of which 199 full-text articles, reports, and presentations were reviewed and 182 items were retained in the final review (see Figure 2). Items needed to address mental health and rural settings and were retained if they described a program, tested an intervention, or focused solely on policy issues (eg, the potential for different models of care in rural settings). Excluded items focused on low and middle income countries or involved telehealth where an urban provider offered direct care without sharing tasks with other providers. The remaining articles were reviewed for content related to: settings where task shifting occurred, providers involved in care, training and supervision for task shifting care, technology support, and challenges (eg, confidentiality) or considerations when task shifting care (eg, the importance of partnerships). Content in these 5 areas was identified in 55 of the articles and synthesized thematically for this review. These articles included 8 from the grey literature and 47 peer-reviewed articles. Among these articles, 23 different programs were outlined and are described in Tables 1 and 2. These programs all either involved CHWs (Table 1) or primarily leveraged primary care providers and/or specialist support to share mental health care delivery (Table 2). Process and outcome measures are included in the tables when available. As many studies were descriptive in nature, the quality of the studies was not evaluated by the authors and synthesis of study outcomes was not feasible for this review.

Figure 2.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Table 1.

Task Sharing Interventions Involving Community Health Workers

| Program Description | Task Shared or New Task |

Control / Comparison Group |

Primary Process and/or Health Outcome Measures Reported |

Author (Yr) and Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home visitation from a nurse and CHW for pregnant women on Medicaid to address stress and mental health |

CHWs add to the nurse home visit program by offering peer support to address chronic stressors, increase access to resources, improve health behaviors, and help engage women in services |

Usual community care that involves a nurse home visit |

↑ women reached and total visits for nurse + CHW intervention; reached ↑ at-risk women with the exception of alcohol and drug risk group |

Roman 2007 U.S. |

| Door-to-door outreach by a CHW to address physical and mental health issues including stress management, substance abuse, domestic violence, depression, and anxiety. CHWs provide information and referrals. |

Community outreach and education |

NA | NA | HRSA report 2011a U.S. |

| CHW-led fotonovela project on depression with an immigrant Latina population |

Community outreach and education |

Discussion on family communication and intergenerational relationships |

↑ depression knowledge; ↑ efficacy to seek treatment; ↓ stigma toward depression treatment |

Hernandez 2013 U.S. |

| Peer Promotora model focused on topics of elder abuse, depression, anxiety, suicide, stigma, and cultural issues around mental health utilization |

Community outreach and education |

NA | NA | Marselian Power- Point 2013a U.S. |

| Promotoras model focused on topics of domestic violence, substance abuse, and harm reduction along with offering individual, group, and family therapy for mental health needs of those who are HIV positive |

Community outreach and education and psychotherapy |

NA | NA |

Garcia newsletter 2006a U.S. |

| Pilot promotora intervention focusing on stress and coping with an immigrant Latina population but also addressing mental health of CHWs offering this intervention |

Community outreach and education |

NA | CHWs had ↑ knowledge of role and stress management, ↑ coping skills and perceived social support, and ↓ depression and stress levels |

Tran 2014 U.S. |

| Behavioral Health Aide (BHA) program integrates a CHW trained in behavioral health into small communities across the state with differing levels of direct and indirect supervision based on level of experience |

Community outreach and education, psychotherapy, assist with crisis response, and case management |

NA | NA | ANTHC BHA Program Guide 2013a U.S. |

| CHWs in the clinic work with depressed patients on the social determinants of health that are correlated with depression, CHW also follows up with patient on depression, medication and possible patient questions, and primary care providers(PCPs) were offered clinical guidelines on depression and PHQ-9 depression symptom measure on patients |

CHW assists primary care team by engaging and following up with patients with depression about their symptoms and treatment while also working with them to address social determinants of health |

CHW follows up with patient on depression, medication, and patient questions, and PCPs offered clinical guidelines on depression and PHQ-9 on patients |

No difference in patient outcomes; Ethnographic findings highlight greater implementation challenges at the experimental clinic compared to control clinic |

Waitzkin 2011 U.S. |

| CHW home-visit intervention developed through health system and public school collaboration to support Latino youth with mental health problems around their children’s mental well- being and school success for at-risk youth |

Community outreach and education |

NA | NA |

Garcia 2012 U.S. |

| CHW added to assertive community treatment (ACT) team working with those with serious psychiatric diagnosis who are at risk for homelessness or homeless. CHW assisted with activities of daily living and leisure activities. |

CHWs add to the ACT team to assist with clients’ daily activities |

2 groups: ACT; brokered case management |

CHW + ACT did not differ from ACT arm in client satisfaction, health outcomes or days in contact with the program |

Wolff 1997; Morse 1997 U.S. |

Indicates item is from the grey literature

Table 2.

Task Sharing Interventions Primarily Leveraging Primary Care Providers and Specialist Support

| Program Description | Task Shared or New Task |

Control / Comparison Group |

Primary Process and /or Health Outcome Measures Reported |

Author (Yr) and Countrya |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telemedicine-based collaborative care mental health support located off- site to enable outreach to small rural clinics that may not be able to support an on-site psychiatrist |

Primary care depression treatment shared between local clinic and remote expert team |

Usual care + educational materials to providers and patients, and depression screening result in electronic medical record |

↑ adherence, mental health status, quality of life and satisfaction and ↓ depression |

Fortney 2007 U.S. |

| Telemedicine-based collaborative care off-site mental health support to clinics including nurse care manager, pharmacist, psychologist, and psychiatrist |

Primary care depression treatment shared between local clinic and remote expert team |

On-site PCP and nurse care manager |

↓ depression which appeared to be attributed to higher fidelity in the telemedicine intervention |

Fortney 2013 U.S. |

| Rural clinics were included in a large effectiveness study of collaborative care but not separated from urban clinics in analysis of effectiveness |

Primary care depression treatment shared between PCPs, care manager and consulting psychiatrist |

NA | NA |

Unutzer 2002 U.S. |

| Shared care / collaborative care in a rural clinic setting worked to improve communication between general practitioners (GP) and psychiatric consultants |

Psychiatrist consults with GPs through regular meetings and videoconference while also travels to 1 rural clinic a day, 3 days a week |

NA | ↑ GP satisfaction with mental health services over 5 years of program |

Samy 2007 Australia |

| Consultation models and collaborative models which both involve primary care providers are described as a means to leverage specialists in child and adolescent psychiatry |

Psychiatrist consults with PCPs |

NA | NA |

Szeftel 2011 U.S. |

| Therapists trained in cognitive behavioral therapy (high- intensity) and computerized CBT guided self-care and psychoeducation groups (low-intensity therapists) integrated into primary care clinics to offer stepped care for depression and anxiety |

High-intensity face-to-face CBT therapists and low- intensity therapists called psychological wellbeing practitioners work with primary care |

NA |

Gyani 2013: Among patients with 2 sessions, 40.3% recovered, 63.7% improved, and 6.6% deteriorated. Compliance with IAPT model appeared to enhance recovery rates. |

Clark 2011; Gyani 2013 U.K. |

| Specialist-guided videoconferencing consults with rural primary care providers offer mental health and substance abuse consultation while also creating a community of practice among rural providers for continued learning and support |

Psychiatrist consults with PCPs, and PCPs support one another through building a community of practice |

NA | On topics of addiction and psychiatry, 16 clinics, 239 clinicians and 105 patients were reached through this program |

Scott 2012 U.S. |

| Consult service using telephone contact for PCPs who want to consult a child psychiatrist |

Psychiatrist consults with PCPs |

NA | PCPs consulted on medication and psychosocial treatment; satisfaction was high |

Hilt 2013 U.S. |

| Televideoconferencing to support psychiatrist in the care team for children with special health care needs in rural areas which can include direct care with the child / family and/or consultation and supervision of community mental health providers |

Psychiatrist consults with PCPs |

NA | Three urban psychiatrists saw 159 patients via telepsychiatry and 210 face-to-face |

Sulzbacher 2006 U.S. |

| Telepsychiatry with team (eg, parent, teacher, social worker, nurse, principal) supporting students at rural K - 12 schools |

Psychiatrist consults with team at the schools |

NA | NA |

Knopf 2013; Saeed 2011 U.S. |

| Telepsychiatry with team supporting students at more rural universities (eg, local psychologist) |

Psychiatrist consults with team in mental health at the university |

NA |

Khasanshina 2008: Those referred to consult were more distressed and needing psychotropic medication; satisfaction lower at first as they worked out technology challenges |

Saeed 2011; Khasanshina 2008 U.S. |

| Multidisciplinary rural mental health care delivery program involving a psychiatric nurse, social worker, occupational therapist, Maori mental health worker, alcohol and drug counselor, psychologist, and forensic psychiatry nurse utilizes telepsychiatry consults in primary care and home visits and an off- hours on- call services for emergencies |

Multidisciplinary program providers shared care. Psychiatrist visits weekly and a child and adolescent psychiatrist and psychogeriatrician visit monthly to work with GPs. Tele-psychiatry also used for case review. |

NA | NA |

Mahmood 2001 New Zealand |

| Group psychotherapy for PTSD treatment trial offered via televideoconferencing from a doctoral-level mental health specialist and included an on-site clinical observer to safeguard against undue emotional escalations |

On-site support person helps with technology difficulties and helps safeguard participants |

NA | NA |

Moreland 2009 U.S. |

All articles were peer reviewed.

The literature describes task sharing that is happening already through the work of CHWs, non-mental health providers in primary care, and mental health specialists. Telehealth can assist sharing of tasks both through supporting care delivery with the help of a remote team member and through provider education. The literature also highlighted some risks and challenges associated with task sharing. While many articles came from the PubMed search, results on CHWs in mental health included considerable items from the grey literature search. The grey literature lacks detail on mental health care delivery, but it gives us insight on this developing focus within the CHW workforce.

Community Health Workers

Community health workers may be involved in mental health care delivery, either through community outreach or clinics. Several models for including CHWs in care and/or outreach have been outlined.18 CHW programs are developing mental health experience. In the Midwest, 23%-71% of CHWs surveyed in each state reported work on mental health topics across Wisconsin, Iowa, Minnesota, and South Dakota,19 while other articles in the review highlighted mental health work involving CHWs in other states such as Alaska, California and Colorado. A 2009 review of the peer-reviewed literature on outcomes in CHW interventions found evidence to support CHW programs showed mixed results in terms of behavior change and health outcomes when studies report such outcomes.20 Only one study within this 2009 review addressed mental health: a randomized controlled trial comparing assertive community treatment (ACT), ACT + CHWs, and brokered case management for those with a serious psychiatric diagnosis who are homeless or at risk for being homeless.21,22 Many of the CHW articles in this review came from the grey literature (ie, 7 of 14 on CHWs) and focused on less severe, more common mental health concerns such as stress management and substance abuse.

Outreach efforts with CHWs include a variety of mental health topics. Programs include home visitation from a nurse and CHW for pregnant women on Medicaid to address stress and mental health,23 and outreach door-to-door by a CHW to address physical and mental health issues including stress management, substance abuse, domestic violence, depression, and anxiety.18 A CHW-led project on depression with an immigrant Latina population created a fotonovela, a small illustrated storybook, which resulted in improved depression knowledge and efficacy to seek treatment alongside decreased stigma toward depression treatment.24 Another program focused on elder abuse, depression and anxiety, suicide awareness and prevention, and stigma and cultural issues around mental health care utilization.25 The SISTERS’ Promotoras Program addressed domestic violence, substance abuse, and harm reduction while also offering individual, group, or family therapy to address mental health needs of those who are HIV positive.26 Mental health prevention and early intervention may also be a focus.27 Beyond community mental health, one CHW program also assessed the effect of the intervention on the mental health of the CHWs.28 CHWs in this study showed an increase in knowledge, coping skills and perceived social support at post-test.28

CHWs may also work in clinics and across clinic and community settings. The Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium Behavioral Health Aide (BHA) Program highlights the potential for CHWs trained in behavioral health and integrated into primary care.29 BHAs work in remote health clinics in Alaska under differing levels of direct and indirect supervision based on their level of certification.29 Another primary care study employed 2 CHWs to work with depressed patients on social determinants of health correlated with depression.30 A collaboration across health system and public school settings involved a CHW home-visit intervention to support parents of Latino youth with mental health problems around their children’s mental well-being and school success.31

Other Providers in Primary Care and Specialist Support

Most primary care task sharing centered on collaborative care for common mental disorders.10,32 Providers that may be involved in collaborative care include primary care providers, nurses, medical assistants, pharmacists, master’s-level social workers or counselors, psychologists, and psychiatrists. In some collaborative care interventions mental health support may be located off-site to enable outreach to several rural clinics.33,34 Regardless of physical location, these mental health specialists support providers in primary care through outreach to patients, monitoring and tracking depression symptoms, suggesting changes in treatment plan when needed, and communicating with the team until the patient’s depression is in remission. The primary care provider remains the prescribing provider if an antidepressant is prescribed and continues to manage the patient’s depression with the assistance of a care manager and psychiatric consultant. Effectiveness studies of collaborative care have included rural populations10 and some have primarily focused on rural populations.33,34 One Australian study focused on a shared care / collaborative care intervention in a rural clinic setting that worked to improve communication between general practitioners and psychiatric consultants.35 In child and adolescent psychiatry, where there are few trained specialists, consultation models and collaborative models that involve local primary care providers hold potential to leverage these skills.36 Finally, the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) initiative in primary care clinics in England, while not focused on collaborative care, has dedicated considerable funds to train therapists in cognitive behavioral therapy who offer stepped care for depression and anxiety in primary care.37,38

Support From Telehealth in Primary Care and Reaching New Settings

Telehealth can support non-mental health providers in primary care through either direct contact from a mental health specialist with the patient and their care team or via consult with these provider(s). Televideo conferencing can effectively support the delivery of collaborative care for depression in primary care.33,34 Telehealth may also support providers through televideo or telephone consult lines, such as through Project ECHO, which offers regular specialist-guided videoconference consults among rural primary care providers for a variety of conditions including mental health and substance abuse consultation.39 Consults help providers treat patients in their communities but also offer a community of practice among providers to enhance learning and reduce feelings of isolation.39 Another consult service uses telephone contact to allow primary care providers to consult with a child psychiatrist in managing children with mental disorders.40

Mental health specialists were also utilized in schools via telehealth. Telepsychiatry interventions hold promise in both rural K – 12 schools41,42 and rural universities.42,43 These interventions involved direct provision of care and consultation with the team assisting the student,41,42 which can include the teacher, parent, social worker, school nurse, and principal in the K – 12 setting41 or local psychologists at the rural university setting.43 Telepsychiatry at schools or other community settings may be particularly convenient for children with severe developmental disabilities.36 Such services can offer considerable cost savings to state Medicaid programs.41

Telepsychiatry may also support novel models involving home visits. One New Zealand study highlighted a multidisciplinary rural mental health care delivery program utilizing telepsychiatry that spans both primary care and home visits. The team approach utilized telehealth, visiting psychiatrists, and local and visiting providers including a psychiatric nurse, social worker, alcohol and drug counselor, forensic psychiatry nurse, occupational therapist, half-time clinical psychologist, and a Maori mental health worker. The team also offered an off-hours on-call service for emergencies. This approach helped address mental health needs and reduced burnout among primary care providers.44

While delivering care via televideo conferencing is generally well accepted and offers equivalent outcomes to in-person care, additional considerations arose within the review. Some individuals may prefer long-distance care such as children with developmental disabilities36 and some individuals in a First Nations community who preferred to talk to someone from outside the community.45 Occasional in-person visits may also be warranted to help develop relationships.46 Also, when using televideo conferencing to help deliver care, an on-site clinical navigator may help make the experience more personal,47 help patients navigate clinical encounters,48 and safeguard against undue emotional escalations.49

Education and Other Support Through Telehealth

Telemedicine, defined as communications networks used to deliver health care services or medical education across geographic areas,50 can also support task sharing through didactic education for providers though such support must consider drawbacks of distance education. Several international articles highlighted education delivered via telemedicine, including online mental health education for emergency department staff in Australia51 and interprofessional education in a mental health program in Canada.52 Teleconference trainings can standardize the course to a larger group across large distances, but provider time constraints are a barrier to completing such trainings.51 Some providers prefer personal experience, colleagues, meetings, and presentations to learn new skills over formal didactic training,53 and some prioritize face-to-face workshops over telehealth delivery.54

Developing appropriate strategies for ongoing training, supervision, and support is important, increasingly so when sharing tasks among providers with differing levels of skills and expertise. Training is especially needed for providers who are not mental health specialists (eg, emergency department staff, CHWs),29,51 but even mental health specialists need training to be effective team members when sharing mental health care tasks with other providers. The importance of ongoing support was emphasized in several articles from Australia. One example involved a 3-year traineeship program with weekly supervision to support aboriginal mental health community workers.55 Other programs from Australia also emphasize the importance of professional supervision for rural mental health practitioners54 and general practitioners.56 In some settings, augmenting in-person training, supervision, and support with distance delivery may be a necessity of the geography of the region, such as in remote areas of Alaska.29

Partnerships With Communities

When searching the literature for other important considerations, the primary topic that surfaced was partnerships with communities when implementing effective task sharing programs. Partnerships when developing and implementing interventions allow for plans that are suitable to the local context and meet local needs.57 For example, a “soft entry” program in which community-based substance abuse counselors offered themselves as a resource to a program led by the aboriginal communities in Australia improved the engagement of aboriginal women in treatment.58 This partnership approach creates a shift in the power dynamic that may be particularly important for indigenous communities that have faced a history of colonization.58 Other articles focusing on partnerships with indigenous communities highlight working with the Tribal Council and other community members59 and an “indigenous team” which incorporates a senior aboriginal cultural consultant.60 Building community partnerships was also emphasized in a study incorporating spiritual leaders, veterans, and mental health providers in a project training clergy as first responders to mental health needs among veterans.61

Challenges

Task sharing may involve challenges related to professional boundaries, confidentiality, burnout, and staff turnover. In a study where social workers offered home-based cognitive behavioral therapy for medically frail older adults while training primary caregivers in general coping skills and how to help the older adult with homework assignments, recruitment of older adults was low despite staff enthusiasm for the program.62 Agencies reported being severely understaffed, and staff had high caseloads with little additional time for these activities. Setting boundaries and avoiding burnout were also substantial challenges.62 In a study with HIV peer counselors, counselors struggled with setting boundaries when working with clients,63 in particular in a substance abuse intervention component of this project.64 It was difficult to recruit peer counselors, in part due to professional boundary challenges.64 Task sharing should also involve clear communication with the team around any limits on mental health tasks for different roles (eg, CHWs) to avoid referral to these resources for something outside their scope of practice.30 Staff turnover of CHWs impacts sustainability of these models of care and remains understudied.65 Concerns with confidentiality can be another risk in task-shifting mental health, especially in small rural settings. Confidentiality was a serious concern in a study with women at a women’s shelter who faced domestic abuse.66 Small rural clinics can present challenges to finding confidential space for discussions,45 as can home visits where providers may encounter family or friends.62

Additional challenges related to task sharing include turf issues or challenges working across vast geographic distances and diverse communities. One study highlighted potential low-grade “turf wars” that surfaced between medical assistants at the clinic and CHWs.30 Differences tied to population density in rural areas, residents’ ethnicity and the economic base of the community make a one-size-fits-all approach to rural mental health impossible.67 The population of Hawai’i, for example, is spread over several islands with two-thirds of residents being Asian or Pacific Islander.68 Such challenges, though, do open opportunities for training more culturally sensitive providers.68 Challenges related to licensing, scopes of practice, and reimbursement for services can arise across these diverse contexts.69,70 Several states in the US have yet to resolve licensing and credentialing issues so clinicians can be reimbursed for consultation across state lines.48,71 One exception to licensing challenges is the VA Health Care System where providers can offer care via telehealth consultation across state lines.72

Discussion

Much is known about some forms of task sharing mental health services, but much still remains unknown. Previous reviews have supported collaborative care for depression and anxiety,32,73 and telemedicine to support delivery of care to rural areas shows great promise as a means to increase the scalability of these models to rural settings.33,34 The widespread use of telemedicine to support providers’ training, supervision and support in the community is an important topic for further development, as there will never be enough specialists, especially in areas such as geriatric or child and adolescent psychiatry. The empirical evidence on incorporating CHWs in care in general, and in mental health care specifically, is sparse but there is great interest in this growing field given the potential for CHWs to increase access to care and facilitate more culturally sensitive care. Future work in task sharing mental health services should also focus on severity of mental health conditions. Collaborative care supports care for common mental disorders. Telehealth may help providers share tasks for those with more severe mental illnesses, but patients and providers may prefer more direct contact opportunities between patient and specialist when treating these conditions. CHWs often focus on health education and supporting care management and navigation for conditions, yet it is unknown how CHWs can best support care for serious mental illness. Beyond work in Alaska,29 little is known on how CHWs might incorporate technology to support their work and/or training when delivering mental health services. Finally, self-care can be seen as the ultimate shifting of tasks to the patient, where the patient can lean back on the system of health care providers when needed. Self-care has been discussed as a means to complement health services.74–77 However, this review did not encompass all of the important work developing in this area, which should be the focus of a subsequent review.

The concept of task sharing is highly relevant for improving access to mental health care in rural and otherwise underserved communities in the US, yet several factors should be considered in implementing task sharing of mental health care. Insights may be gleaned from challenges to task sharing mental health services in low and middle income countries (eg, distress among the workforce, acceptance of the added workforce by other health care staff).78 An influx of financial support may, however, remedy some of these challenges.78 Overall, low income countries have focused more on utilizing CHWs in the community while middle income countries have successfully implemented collaborative care in primary care. Limited health care resources in low income countries may explain challenges related to working with primary care.17 In comparison with areas where task sharing is occurring globally, many rural and low resource primary care settings in the US have financial resources to implement collaborative care, telemental health, and programs involving CHWs. The question for these communities then becomes, “given our unique population, geographic location, and supply of providers, what task shifting model(s) are appropriate for our community?” The answer to this question must account for training and supervision when task sharing to monitor and address expected risks and challenges. For a more comprehensive approach to answering this question at the community level, we believe it is important to clearly specify all relevant tasks involved and develop a systematic “shared workflow” to clarify how team members participate in and coordinate care. Defining these tasks may also illuminate some tasks (eg, CHW outreach, care manager follow-up) that were not previously a part of mental health delivery. These additional tasks highlight the potential for task sharing to improve both access and quality of care when there is clear communication among the team and adequate training, support and supervision from mental health specialists.

The literature in our review gives numerous examples of how to apply task sharing principles, but it also suggests there are a number of important questions to be addressed through additional research. These questions include:

What are the most effective methods to engage and retain patients and providers in intervention programs that involve task sharing?

What are the most effective ways of providing initial and ongoing training and supervision for providers participating in task sharing interventions for mental health? How are these needs of rural health providers best supported? What are the costs for this level of support or costs associated with lack of support (eg, cost tied to staff attrition)?

How should task sharing approaches differ across communities given differing cultural factors, geographic factors and local resources?

How should task sharing approaches differ by mental health target conditions (eg, common mental disorders, substance use disorders, trauma-related disorders, severe and persistent psychotic disorders)?

How can mental health specialists such as psychiatrists and psychologists be trained to provide population-level oversight, consultation, and supervision needed to support rural providers in task sharing interventions?

How can technology best facilitate task sharing approaches in rural mental health care?

How can the various professions/guilds create enabling conditions and prevent turf/guild issues from arising to support task sharing through their appropriate regulatory processes?

How can other barriers to developing task sharing approaches be addressed (eg, privacy concerns, concerns about liability, uncertainty about roles)?

How can task sharing in mental health care in rural or otherwise underserved communities be implemented in a way that is sustainable?

To address these questions, we recommend several types of future research:

A systematic effort to collect and “map” information on existing task sharing approaches in rural and otherwise underserved settings in the US and abroad using a mixed methods approach.

Research on partnership strategies with communities that yield the most promising task sharing approaches in rural and otherwise underserved settings.

A systematic assessment of the available workforce in diverse settings and its interest and capacity to learn and/or assume relevant tasks.

A systematic assessment of individuals in rural mental health settings to examine their interest in and comfort with using mental health services that use diverse task sharing strategies.

A systematic effort to estimate resources and costs associated with various task sharing approaches used.

A systematic assessment of how to scale up the acquisition and maintenance of minimum standards of competency of CHWs and other non-specialist workers in real world clinical settings.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that can compare the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of various task sharing approaches. Models involving CHWs would particularly benefit from more rigorous study such as staggered RCTs that assess patient outcomes and also potentially mental health outcomes for CHWs.

Research examining policy, financial, or regulatory approaches that support or impede the implementation of effective task sharing approaches.

Conclusion

One limitation of the review was its focus on the PubMed database. The authors did not include PsychInfo, CINHAL, and Google Scholar in the search. We focused on one popular database for peer-reviewed literature alongside a grey literature search to understand task sharing as it is developing outside this peer-reviewed literature. It is possible we missed important articles on this topic. Another limitation is the end date for the review of August 31, 2013. As this study developed for a report to the ORMHR at NIMH as mentioned earlier, this cut-off date coincides with search dates for that report.

Despite these limitations, these research questions and recommendations for future research that we highlight offer a promising road forward to improve the use of evidence-based models and test new models of care that share tasks among a wider team of mental health and non-mental health professionals. This is still a burgeoning area with many directions for future research. Such research should consider the costs associated with these new models of care to ensure they are safe, effective and scalable, while assessing costs for ongoing training, support, and supervision. Including local partners such as clinicians and administrators in the development of research will help ensure care efficiently utilizes local resources and expertise. Patients and providers within the community can be valuable partners in research on benefits, risks, challenges, and unintended consequences of task sharing mental health care that may pose barriers to development and implementation of models of care. This inclusion of stakeholders is well aligned with the promising direction of patient-centered outcomes research and comparative effectiveness research. There is great promise for task sharing to meet mental health needs in rural and other low resources areas in the US. The research opportunities presented here can help establish the best models across different contexts and conditions to improve access to and possibly quality of mental health care in diverse rural and low resource settings in the US.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the experts in the areas of task shifting, mental health, and health disparities who helped us broaden our search of the literature for this review.

Funding: We would like to acknowledge funding from the Office of Rural Mental Health Research at the National Institute of Mental Health in support of this review which resulted in a White Paper for this office (#HHSN271201300463P) and funding from the Geriatric Mental Health Services Research Fellowship through the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH073553).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed August 25, 2015];Frequently asked questions. Available from https://ask.census.gov.

- 2.Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Thomas KC, Morrissey JP. County-level estimates of mental health professional supply in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1315–1322. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.10.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perkins DA, Roberts R, Sanders T, Rosen A. Far West Area Health Service mental health integration project: model for rural Australia? Aust J Rural Health. 2006;14:105–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2006.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox J, Merwin E, Blank M. De facto mental health services in the rural south. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1995;6:434–468. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Task shifting: global recommendations and guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. The optimal mix of services for mental health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel V, Goel DS, Desai R. Scaling up services for mental and neurological disorders in low-resource settings. Int Health. 2009;1:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.inhe.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel V. Global mental health: from science to action. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2012;20:6–12. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2012.649108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chisholm D, Flisher AJ, Lund C, et al. Scale up services for mental disorders: a call for action. Lancet. 2007;370:1241–1252. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bass J, Neugebauer R, Clougherty KF, et al. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: 6-month outcomes: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:567–573. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.6.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolton P, Bass J, Neugebauer R, et al. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2003;289:3117–3124. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buttorff C, Hock RS, Weiss HA, et al. Economic evaluation of a task-shifting intervention for common mental disorders in India. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:813–821. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.104133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, Roberts C, Creed F. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:902–909. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61400-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:2086–2095. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61508-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen I, Ssebunnya J, Bhana A, Baillie K. Lessons from case studies of integrating mental health into primary health care in South Africa and Uganda. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2011;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Community Health Workers Evidence-Based Models Toolbox. Washington, DC: Health Resources and Services Administration, Office of Rural Health Policy; 2011. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardeman R. Community Health Workers in the Midwest: Understanding and Developing the Workforce. Saint Paul, MN: Wilder Research; 2012. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski J, Nishikawa B, et al. Outcomes of Community Health Worker Interventions. Evidence Report / Technology Practice Center under Contract No. 290 2007 10056 I.) AHRQ Publication No. 09-E014. Rockville, MD: gency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2009. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolff N, Helminiak TW, Morse GA, Calsyn RJ, Klinkenberg WD, Trusty ML. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of three approaches to case management for homeless mentally ill clients. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:341–348. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morse GA, Calsyn RJ, Klinkenberg WD, et al. An experimental comparison of three types of case management for homeless mentally ill persons. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:497–503. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roman LA, Lindsay JK, Moore JS, et al. Addressing mental health and stress in Medicaid-insured pregnant women using a nurse-community health worker home visiting team. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24:239–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernandez MY, Organista KC. Entertainment-education? A fotonovela? A new strategy to improve depression literacy and help-seeking behaviors in at-risk immigrant Latinas. Am J Community Psychol. 2013;52:224–235. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9587-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marselian Z, Areizaga A. [Accessed August 25, 2015];Engaging Low Income Culturally Diverse Older Adults in Health Promotion through an Innovative Peer Promotora Model [PowerPoint slides] Available from http://www.chpfs.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia B. Sisters of Color United for Education Newsletter. Denver, CO: Sisters of Color United for Education; 2006. Winter. Sisters Promotoras: Saving lives in Denver, Mexico and Guatemala. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhett-Mariscal W. Policy Report. Sacremento, CA: California Institute for Mental Health; 2008. Nov, Promotores in Mental Health in California and the Prevention and Early Intervention Component of the MHSA. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tran AN, Ornelas IJ, Perez G, Green MA, Lyn M, Corbie-Smith G. Evaluation of Amigas Latinas Motivando el Alma (ALMA): a pilot promotora intervention focused on stress and coping among immigrant Latinas. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;16:280–289. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9735-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.BHA. Behavioral Health Aide Program. Anchorage, AK: Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium; 2013. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waitzkin H, Getrich C, Heying S, et al. Promotoras as mental health practitioners in primary care: a multi-method study of an intervention to address contextual sources of depression. J Community Health. 2011;36:316–331. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9313-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia C, Hermann D, Bartels A, Matamoros P, Dick-Olson L, Guerra de Patino J. Development of project wings home visits, a mental health intervention for Latino families using community-based participatory research. Health promotion practice. 2012;13:755–762. doi: 10.1177/1524839911404224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2. Cd006525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Edlund MJ, et al. A randomized trial of telemedicine-based collaborative care for depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1086–1093. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0201-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Mouden SB, et al. Practice-based versus telemedicine-based collaborative care for depression in rural federally qualified health centers: a pragmatic randomized comparative effectiveness trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:414–425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12050696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samy DC, Hall P, Rounsevell J, Carr R. ‘Shared care - shared dream’: model of shared care in rural Australia between mental health services and general practitioners. Aust J Rural Health. 2007;15:35–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szeftel R, Mandelbaum S, Sulman-Smith H, et al. Telepsychiatry for children with developmental disabilities: applications for patient care and medical education. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2011;20:95–111. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark DM. Implementing NICE guidelines for the psychological treatment of depression and anxiety disorders: the IAPT experience. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2011;23:318–327. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2011.606803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gyani A, Shafran R, Layard R, Clark DM. Enhancing recovery rates: lessons from year one of IAPT. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51:597–606. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott JD, Unruh KT, Catlin MC, et al. Project ECHO: a model for complex, chronic care in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18:481–484. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.GTH113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hilt RJ, Romaire MA, McDonell MG, et al. The Partnership Access Line: evaluating a child psychiatry consult program in Washington State. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:162–168. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knopf A. School-based telehealth brings psychiatry to rural Georgia. Behav Healthc. 2013;33:47–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saeed SA, Diamond J, Bloch RM. Use of telepsychiatry to improve care for people with mental illness in rural North Carolina. N C Med J. 2011;72:219–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khasanshina EV, Wolfe WL, Emerson EN, Stachura ME. Counseling center-based tele-mental health for students at a rural university. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:35–41. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahmood T, Romans S, Forbes L. The future of specialist psychiatric services in rural New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2001;114:294–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gibson K, O’Donnell S, Coulson H, Kakepetum-Schultz T. Mental health professionals’ perspectives of telemental health with remote and rural First Nations communities. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17:263–267. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2011.101011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sulzbacher S, Vallin T, Waetzig EZ. Telepsychiatry improves paediatric behavioural health care in rural communities. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12:285–288. doi: 10.1258/135763306778558123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swinton JJ, Robinson WD, Bischoff RJ. Telehealth and rural depression: physician and patient perspectives. Fam Syst Health. 2009;27:172–182. doi: 10.1037/a0016014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pruthi S, Stange KJ, Malagrino GD, Jr, Chawla KS, LaRusso NF, Kaur JS. Successful implementation of a telemedicine-based counseling program for high-risk patients with breast cancer. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morland LA, Greene CJ, Rosen C, Mauldin PD, Frueh BC. Issues in the design of a randomized noninferiority clinical trial of telemental health psychotherapy for rural combat veterans with PTSD. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sood S, Mbarika V, Jugoo S, et al. What is telemedicine? A collection of 104 peer-reviewed perspectives and theoretical underpinnings. Telemed J E Health. 2007;13:573–590. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hills DJ, Robinson T, Kelly B, Heathcote S. Outcomes from the trial implementation of a multidisciplinary online learning program in rural mental health emergency care. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2010;23:351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Church EA, Heath OJ, Curran VR, Bethune C, Callanan TS, Cornish PA. Rural professionals’ perceptions of interprofessional continuing education in mental health. Health Soc Care Community. 2010;18:433–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jameson JP, Farmer MS, Head KJ, Fortney J, Teal CR. VA community mental health service providers’ utilization of and attitudes toward telemental health care: the gatekeeper’s perspective. J Rural Health. 2011;27(4):425–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bulbrook KM, Carey TA, Lenthall S, Byers L, Behan KP. Treating mental health in remote communities: what do remote health practitioners need? Rural Remote Health. 2012;12(4):2346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bartik W, Dixon A, Dart K. Aboriginal child and adolescent mental health: a rural worker training model. Australas Psychiatry. 2007;15:135–139. doi: 10.1080/10398560701196745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hodgins G, Judd F, Kyrios M, Murray G, Cope A, Sasse C. A model of supervision in mental health for general practitioners. Australas Psychiatry. 2005;13:185–189. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1665.2005.02186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ulzen T, Williamson L, Foster PP, Parris-Barnes K. The evolution of a community-based telepsychiatry program in rural Alabama: lessons learned-a brief report. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49:101–105. doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allan J, Campbell M. Improving access to hard-to-reach services: a soft entry approach to drug and alcohol services for rural Australian Aboriginal communities. Soc Work Health Care. 2011;50:443–465. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2011.581745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gibson KL, Coulson H, Miles R, Kakekakekung C, Daniels E, O’Donnell S. Conversations on telemental health: listening to remote and rural First Nations communities. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11:1656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fielke K, Cord-Udy N, Buckskin J, Lattanzio A. The development of an ‘Indigenous team’ in a mainstream mental health service in South Australia. Australas Psychiatry. 2009;17(Suppl 1):S75–S78. doi: 10.1080/10398560902950510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sullivan S, Pyne JM, Cheney AM, Hunt J, Haynes TF, Sullivan G. The pew versus the couch: relationship between mental health and faith communities and lessons learned from a VA/Clergy partnership project. J Relig Health. 2013;53(4):1267–1282. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9731-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaufman AV, Scogin FR, Burgio LD, Morthland MP, Ford BK. Providing mental health services to older people living in rural communities. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2007;48:349–365. doi: 10.1300/j083v48n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hilfinger Messias DK, Moneyham L, Vyavaharkar M, Murdaugh C, Phillips KD. Embodied work: insider perspectives on the work of HIV/AIDS peer counselors. Health Care Women Int. 2009;30:572–594. doi: 10.1080/07399330902928766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boyd MR, Moneyham L, Murdaugh C, et al. A peer-based substance abuse intervention for HIV+ rural women: a pilot study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2005;19:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nkonki L, Cliff J, Sanders D. Lay health worker attrition: important but often ignored. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:919–923. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.087825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tschirch P, Walker G, Calvacca LT. Nursing in tele-mental health. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2006;44:20–27. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20060501-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rainer JP. The road much less travelled: treating rural and isolated clients. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:475–478. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chung-Do J, Helm S, Fukuda M, Alicata D, Nishimura S, Else I. Rural mental health: implications for telepsychiatry in clinical service, workforce development, and organizational capacity. Telemed J E Health. 2012;18:244–246. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2011.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gamm LD. Mental health and substance abuse services among rural minorities. J Rural Health. 2004;20(2):206–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2004.tb00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mitka M. Telemedicine eyed for mental health services: approach could widen access for older patients. JAMA. 2003;290(14):1842–1843. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Benavides-Vaello S, Strode A, Sheeran BC. Using technology in the delivery of mental health and substance abuse treatment in rural communities: a review. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2013;40:111–120. doi: 10.1007/s11414-012-9299-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barnwell SV, Juretic MA, Hoerster KD, Van de Plasch R, Felker BL. VA Puget Sound Telemental Health Service to rural veterans: a growing program. Psychol Serv. 2012;9:209–211. doi: 10.1037/a0025999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Coventry PA, Hudson JL, Kontopantelis E, et al. Characteristics of effective collaborative care for treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-regression of 74 randomised controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Proudfoot J, Goldberg D, Mann A, Everitt B, Marks I, Gray JA. Computerized, interactive, multimedia cognitive-behavioural program for anxiety and depression in general practice. Psychol Med. 2003;33:217–227. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702007225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Williams AD, Andrews G. The effectiveness of Internet cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) for depression in primary care: a quality assurance study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kuhn E, Greene C, Hoffman J, et al. Preliminary evaluation of PTSD Coach, a smartphone app for post-traumatic stress symptoms. Mil Med. 2014;179:12–18. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reger GM, Hoffman J, Riggs D, et al. The “PE coach” smartphone application: an innovative approach to improving implementation, fidelity, and homework adherence during prolonged exposure. Psychol Serv. 2013;10:342–349. doi: 10.1037/a0032774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Padmanathan P, De Silva MJ. The acceptability and feasibility of task-sharing for mental healthcare in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2013;97:82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]