Abstract

Contrary to common belief, the brain appears to increase the complexity from the perceived object to the idea of it. Topological models predict indeed that: (a) increases in anatomical/functional dimensions and symmetries occur in the transition from the environment to the higher activities of the brain, and (b) informational entropy in the primary sensory areas is lower than in the higher associative ones. To demonstrate this novel hypothesis, we introduce a straightforward approach to measuring island information levels in fMRI neuroimages, via Rényi entropy derived from tessellated fMRI images. This approach facilitates objective detection of entropy and corresponding information levels in zones of fMRI images generally not taken into account. We found that the Rényi entropy is higher in associative cortices than in the visual primary ones. This suggests that the brain lies in dimensions higher than the environment and that it does not concentrate, but rather dilutes messages coming from external inputs.

Keywords: Entropy, Topology, fMRI, Tessellation

Introduction

Sequential processing of information is hierarchical so that initial, low-level inputs of primary sensory areas are transformed into representations. Integration emerges at multiple processing associative cortical stages (Freeman 2007; Werner and Noppeney 2009; Nieuwenhuys et al. 2008). Sensory inputs are progressively concentrated, from the primary sensory areas to higher associative ones. As cortical distance from the input increases, brain functions organize messages in global gradients of abstraction, so that spatially progressive representation amalgamation emerges (Taylor et al. 2015). In sum, the current paradigm talks about a brain that, through the limited human sensory repertoire, extracts and concentrates information from the environment’s overwhelming complexity, focusing just on what is useful for the individual preservation.

However, recent advances suggest that the brain is more complex than previously thought (Tozzi 2015) and displays a number of dimensions and symmetries higher than commonly believed (Tozzi and Peters 2016a, b; Xing et al. 2016; Peters et al. 2017). This means that external inputs progressively increase their complexity, when spikes cross the brain towards higher associative cortices. Here we hypothesize that sensory inputs are progressively diluted, when passing from the lower sensory areas to the higher associative ones. In other words, the “concept” (or the “idea”) could be more complex than the corresponding inputs from the external world. The brain activity might lead to increases, and not decreases, of complexity, compared with the surrounding environment. In order to test our claim, we evaluated, through novel neuroimaging techniques, the entropy values in different cortical areas after visual stimuli presentation and showed that the associative areas manifest more information than the primary sensory ones.

Materials and methods

Samples

We evaluated 16 fMRI images from visual tasks experiments, which illustrate the activity of different brain areas during vision. The images, taken from Mandelkow et al. (2016), display a widely distributed fMRI response throughout the brain, elicited by basic vision and object recognition. A voxel-wise ANOVA F-statistic map (threshold p < 1%, uncorrected) was superimposed on the T1-weighted anatomical MRI of one representative subject (16 axial slices in radiological convention). Each tessellated image leads to the MNC mesh clustering described in the next paragraph.

Nucleus clustering in Voronoï tilings

Through computational techniques described in Peters et al. (2016, 2017), we detected, in the above-mentioned images, a set of keypoint sites S (also called generating points), each with a different orientation angle. Each site s is used to derive what is known as a Voronoï region of s, which is a polygonal shape contain all surface points that are nearer s than to any other site in S (Peters 2016; Edelsbrunner 2006; Duyckaerts and Godefroy 2000; Frank and Hart 2010). A Voronoï region V(s) of a site s is defined by

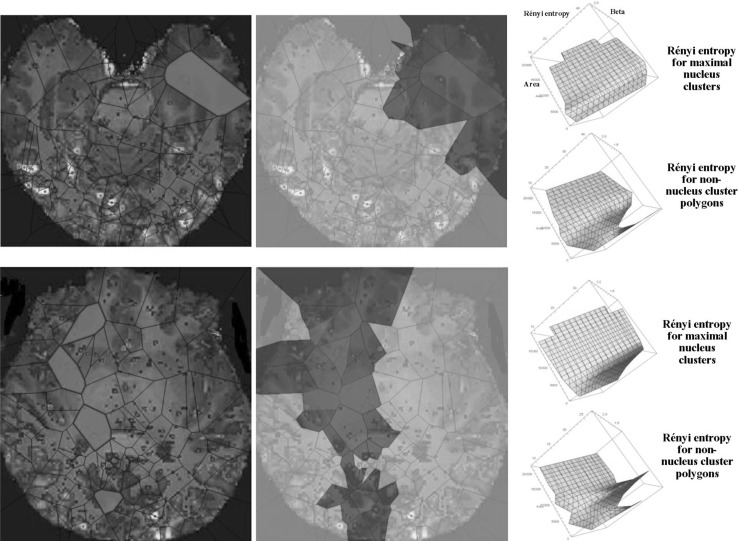

A tessellated image results from finding all Voronoï regions on the image. The end result is a collection of convex Voronoï regions that reveal varying information levels in tessellated fMRI images. Each Voronoï region is the center of a cluster of polygonal regions called a nucleus cluster. A cluster with the highest number of adjacent Voronoï regions is called a maximal nucleus cluster (MNC) (Peters and Inan 2016; Peters 2016) (Fig. 1, left column). A MNC, which highlights singular regions of fMRI images, contains a nucleus polygon with the highest number of adjacent Voronoï regions (Fig. 1, central column). In effect, each maximal nucleus tells us something different about every region of a tiled fMRI image, since we include, in the description of a maximal nucleus, the number of adjacent regions as well as the orientation angles of the nucleus generating point. In sum, in a Voronoï tessellation of an fMRI image, of particular interest is the presence of MNCs, i.e., clusters with nuclei having the highest number of adjacent polygons.

Fig. 1.

Voronoï tessellation and MNCs in two fMRI images, taken from Mandelkow et al. (2016). The left column depicts Maximal Voronoi regions. Each red dot in the tiling stands for a generating point with particular features, such as gradient orientation angle and brightness. No two red dots have the same description. For this reason, every polygonal Voronoï region has a slightly different shape. Red polygons show MNCs. They are of particular interest, since their generating points have a gradient orientation that is different from the gradient orientation of any other generating point in this particular tiling. The central column displays cortical MNCs, i.e., the areas with the higher number of adjacent polygons. The right column illustrates informational levels in the two fMRI images, in particular the Rényi entropy values of the corresponding MNCs, compared with the surrounding areas. For every sample, the Rényi entropy values versus number polygon areas of MNC (upper part) and outside MNC (lower part) are displayed. MNC Nuclei surrounded by polygons with smaller areas have higher Rényi entropy, which tells us that smaller MNC areas yield more cortical information than MNCs with larger areas

Information levels in fMRI nucleus clusters

MNCs reveal brain regions with higher levels of cortical information, in comparison with non-MNC cortical regions, that uniformly yield less information. Using Rényi entropy (Rényi 1961, 1966, 1982; Bromiley et al. 2010), as a measure of information, we previously demonstrated that the nuclei in MNCs have the highest concentration of adjacent polygons, compared to all non-MNC polygons (Peters et al. 2017). This finding points towards MNCs yielding higher information than any of the polygon areas outside the MNCs (Fig. 1, right column). In sum, Rényi entropy provides a measure of the information in MNCs and the surrounding zones of fMRI images. This means that the MNCs encompass higher entropy values, and therefore higher information, which contrasts with the lower information in the surrounding non-MNC zones.

Results

Each frame from Mandelkow et al. (2016) showed that stimulus-correlated fMRI activity is widespread in the occipital and ventral temporal cortices, consistent with their established involvement in basic vision and object recognition. For each frame, we produced tessellated images with one or more maximal mesh regions. Furthermore, we generated tessellated images showing one or more MNCs. The most of MNCs were found to be located in anterior or central brain zones, far from the posterior primary visual sensory areas. The entropy values were higher in the associative zones than in the primary sensory ones. This means that the associative brain areas, during vision, display more activity than the surrounding ones, including the primary visual area. See Fig. 1 for further details.

Discussion

The current paradigm describes a hierarchical landscape of cognition, where a relatively linear and continuous increase in symbolic content occurs over network-depth. A continuum of stratified landscapes takes place in a hierarchical connectome, where a graded order of class is represented by a diagram of connected nodes. Starting from external inputs, an emergent aggregation of functions gives rise to abstractions processing, where abstraction is defined as a process creating general concepts of representation, by emphasizing common features (Taylor et al. 2015). A structural pyramid of the human connectome with gross network-depth directionality can be sketched. Concrete regions at the base of pyramid, connected to the outside world, are related to simple perceptions, sensory processing or physical actions. Abstract regions at the pinnacle of the pyramid, which are deepest in the brain network and least connected with the outside world, are related to more abstract concepts and symbols. Behavioral elements are conceptualized as brain functions, tasks or behaviors. This means that abstract behaviors start with sensory inputs and the information representation flow converges towards less complex schemes, e.g., the ideas (Pexman et al. 2013). In sum, unified concepts tend to compress and amalgamate the information content of an idea or an observable event, in order to retain only information which is relevant for an individualized goal or action (Taylor et al. 2015).

Here we proposed and tested an alternative hypothesis, where the above-mentioned pyramid of complexity is inverted: the abstract concepts are more intricate and contain more information than the external world. The brain does not extract and concentrate the meaning of external objects in simple ideas, rather it dilutes the meaning of external objects in complicated ideas. The information is not aggregated, rather it is scattered in the brain. Recent papers suggest that the brain activity might be multidimensional and shaped in guise of a donut-like structure (see, for example, Tozzi and Peters 2016a). This means that the brain function lies in dimensions higher than the environment. Brain activity can be compared to a phase space where projections take place among regions temporarily equipped with different functional dimensions, each one mapping the other. In this powerful topologic framework, the world external to the observer is a single set of objects, while the world internal to the observer is many sets of objects with matching description (Tozzi and Peters 2016b). Single descriptions of biologically significant environmental inputs become matching descriptions in our thoughts. The object’s concept lies in a dimension higher than the object. To make an example, mental images of cats are not pale copies of cats: while mental images are matching descriptions, real images are single descriptions. Thus, contrary to common belief, the object’s concept is more intricate than the object.

This means that the primary sensory areas might display less entropy than the associative areas. To test our hypothesis, we needed to evaluate the changes in entropy values in fMRI images, in given timescales and in different areas. We used a novel image analysis technique. The major new elements in the evaluation of fMRI images are nucleus clusters, maximal nucleus clusters, strongly near maximal nucleus clusters, convexity structures that occur whenever max nucleus clusters intersect. We showed that in a Voronoï tessellation of an fMRI image, of particular interest is the presence of MNCs, i.e., clusters with the highest number of adjacent polygons. We demonstrated that MNC reveal regions of the brain with higher levels of cortical information, in comparison with non-MNC cortical regions. We showed that, in touch with our hypothesis, such brain zones with higher levels of cortical information correspond to associative areas.

Contributor Information

James F. Peters, Email: James.peters3@umanitoba.ca

Arturo Tozzi, Email: tozziarturo@libero.it.

Sheela Ramanna, Email: s.ramanna@uwinnipeg.ca.

Ebubekir İnan, Email: einan@adiyaman.edu.tr.

References

- Bromiley, PA, Thacker, NA, Bouhova-Thacker, E (2010) Shannon entropy, Renyi entropy, and information. Tina 2004-004, Statistic and Inf Series, Imaging Science and Biomedical Engineering, The University of Manchester, UK

- Duyckaerts G, Godefroy G. Voronoï tessellation to study the numerical density and the spatial distribution of neurons. J Chem Neuroanat. 2000;20(1):83–92. doi: 10.1016/S0891-0618(00)00064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelsbrunner H. Geometry and topology for mesh generation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Frank NP, Hart SM. A dynamical system using the Voronoï tessellation. Am Math Mon. 2010;117(2):92–112. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman WJ. Definitions of state variables and state space for brain-computer interface: part 1. Multiple hierarchical levels of brain function. Cogn Neurodyn. 2007;1(1):3–14. doi: 10.1007/s11571-006-9001-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelkow H, de Zwart JA, Duyn JH. Linear discriminant analysis achieves high classification accuracy for the BOLD fMRI response to naturalistic movie stimuli. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:128. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuys R, Voogd J, van Huijzen C. The human central nervous system. Heidelberg: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Peters JF. Computational proximity. In: Intelligent Systems Reference Library, editor. Excursions in the topology of digital images. Berlin: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Peters JF, İnan E (2016) Strongly near Voronoï nucleus clusters. 1–7. arXiv:1602(03734)

- Peters JF, Tozzi A, Ramanna S. Brain tissue tessellation shows absence of canonical microcircuits. Neurosci Letters. 2016;626:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JF, Ramanna S, Tozzi A, Inan E. BOLD-independent computational entropy assesses functional donut-like structures in brain fMRI image. Frontiers Hum Neurosci. 2017 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pexman PM, Siakaluk PD, Yap MJ. Introduction to the research topic meaning in mind: semantic richness effects in language processing. Front: Hum Neurosci; 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rényi A (1961) On measures of entropy and information. In: Proceedings of the fourth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability, vol. I, University of California Press, Berkeley, pp 547–457 (MR0132570)

- Rényi A. On the amount of information in a random variable concerning an event. J Math Sci. 1966;1:30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rényi A. Tagebuch über die Informationstheorie. Berlin: VEB Deutcher der Wissenschaften; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P, Hobbs JN, Burroni J, Siegelmann HT. The global landscape of cognition: hierarchical aggregation as an organizational principle of human cortical networks and functions. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18112. doi: 10.1038/srep18112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi A. Information processing in the CNS: a supramolecular chemistry? Cogn Neurodyn. 2015;9(5):463–477. doi: 10.1007/s11571-015-9337-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi A, Peters JF. Towards a fourth spatial dimension of brain activity. Cogn Neurodyn. 2016;10(3):189–199. doi: 10.1007/s11571-016-9379-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi A, Peters JF. A topological approach unveils system invariances and broken symmetries in the brain. J Neurosci Res. 2016;94(5):351–365. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner S, Noppeney U. Superadditive responses in superior temporal sulcus predict audiovisual benefits in object categorization. Cereb Cortex. 2009;20(8):1829–1842. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing M, Ajilore O, Wolfson OE, Abbott C, MacNamara A, et al. Brain informatics and health. Ser Lect Notes Comput Sci. 2016;9919:149. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-47103-7_15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]