Abstract

Marital status has been found to be a prognostic factor for survival in various cancers, but its role in gallbladder cancer (GBC) has not been fully studied. In this study, we used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER)-registered database to analyze the survival of GBC patients with different marital status. A total of 6,627 GBC patients were selected from SEER database from 2004 to 2013. The age, race, grade, histologic type, AJCC stage, SEER stage and marital status were identified as independent prognostic factors. Married GBC patients had a higher 5-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) than that of unmarried ones (20.1% v.s. 17.8%, P < 0.05). Subgroup analyses showed that widowed patients had 14.0% less of 5-year CSS compared to married ones of stage I (55.9% v.s. 41.9%, P < 0.05), 14.7% of stage II (15.6% v.s. 10.9%, P < 0.05), and 1.5% of stage III + IV (2.9% v.s. 1.4%, P < 0.05). In addition, single is an independent prognostic factor at stage III + IV (HR = 1.225, 95%CI 1.054–1.423, P = 0.008). These results indicated that widowed patients were at a high risk of cancer-specific mortality and marriage can be a protective prognostic factor in CSS.

Introduction

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is one of the most common malignant cancer in biliary system1. Despite many advances in the diagnosis and treatment of this disease, the prognosis of GBC is still poor, with less than 5% of 5-year survival1–3. Studies have shown that the marital status has significant impacts on the survival of various cancers, including colorectal4, gastric5, 6, pancreatic7 and tracheal8 cancer. Married individuals have better prognosis and lower mortality of major causes of death compared to those never married, separated, widowed, or divorced9–11. Furthermore, marital status has been demonstrated as an independent prognostic factor of survival in various cancers12–15. Li et al. reported that unmarried patients were at greater risk of cancer specific mortality while widowed patients were at the highest risk of death compared to other groups, which were analyzed in 112, 776 colorectal cancer patients selected from SEER data4. Jin et al. demonstrated that marriage had a protective effect against undertreatment and cause-specific mortality in gastric cancer5. But few study focused on the influence of marital status on the survival of GBC patients. Therefore, we systematically investigated the effect of marital status on the clinicopathological features and survival of GBC patients in this study.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 6,627 GBC patients between 2004 and 2013 were selected from SEER database, including 1,959 males and 4,668 females. Among the 6,627 patients, the average age is 70 (range of 21–104). 3451 patients are married; 686 are divorced or separated; 1586 are widowed and 904 are single. The demographic and characteristics of patients were summarized in Table 1. The marital status of patients is correlated to sex, age, race, histologic type, AJCC stage and SEER stage in GBC (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with GBC in SEER database.

| Parameter | Characteristic | N | Married | Divorced/ Separated | Widowed | Single | χ2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | |||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1959 | 1356(39.29) | 160(23.32) | 172(10.84) | 271(29.98) | 436.672 | P < 0.001 | |

| Female | 4668 | 2095(60.71) | 526(76.68) | 1414(89.16) | 633(70.02) | |||

| Age | ||||||||

| <60 | 1651 | 999(28.95) | 225(32.80) | 62(3.91) | 365(40.38) | 542.421 | P < 0.001 | |

| ≥60 | 4976 | 2452(71.05) | 461(67.20) | 1524(96.09) | 539(59.62) | |||

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 5055 | 2661(77.11) | 517(75.36) | 1238(78.06) | 639(70.69) | 164.611 | P < 0.001 | |

| Black | 802 | 311(9.01) | 119(17.35) | 177(11.16) | 195(21.57) | |||

| *Others | 748 | 468(13.56) | 49(7.14) | 168(10.59) | 63(6.97) | |||

| Unknow | 22 | 11(0.32) | 1(0.15) | 3(0.19) | 7(0.77) | |||

| Grade | ||||||||

| Well differentiated | 685 | 368(10.66) | 60(8.75) | 167(10.53) | 90(9.96) | 19.991 | P = 0.067 | |

| Moderately differentiated | 1982 | 1028(29.79) | 198(28.86) | 475(29.95) | 281(31.08) | |||

| Poorly differentiated | 1853 | 995(28.83) | 190(27.70) | 409(25.79) | 259(28.65) | |||

| Undifferentiated | 122 | 76(2.20) | 12(1.75) | 22(1.39) | 12(1.33) | |||

| Unkown | 1985 | 984(28.52) | 226(32.94) | 513(32.34) | 262(28.98) | |||

| Histologic type | ||||||||

| Adenomas adenocarcinomas | 5388 | 2850(82.58) | 552(80.47) | 1263(79.63) | 723(79.98) | 63.583 | P < 0.001 | |

| Epithelial neoplasms | 435 | 217(6.29) | 42(6.12) | 115(7.25) | 61(6.75) | |||

| Cystic, mucinous and serous neoplasms | 371 | 189(5.48) | 41(5.98) | 82(5.17) | 59(6.52) | |||

| Unspecified neoplasms | 151 | 46(1.33) | 27(3.93) | 67(4.23) | 11(1.22) | |||

| #Others | 282 | 149(4.32) | 24(3.50) | 59(3.72) | 50(5.53) | |||

| AJCC Stage | ||||||||

| I | 1755 | 890(25.79) | 165(24.05) | 465(29.32) | 235(26.00) | 50.702 | P < 0.001 | |

| II | 1872 | 984(28.51) | 185(26.97) | 445(28.06) | 258(28.54) | |||

| III | 173 | 93(2.70) | 23(3.35) | 34(2.14) | 23(2.54) | |||

| IV | 2351 | 1283(37.18) | 265(38.63) | 486(30.64) | 317(35.07) | |||

| UNK Stage | 476 | 201(5.82) | 48(7.00) | 156(9.84) | 71(7.85) | |||

| SEER Stage | ||||||||

| Localized | 2133 | 1049(30.40) | 199(29.01) | 594(37.45) | 291(32.19) | 67.165 | P < 0.001 | |

| Regional | 1584 | 857(24.83) | 161(23.47) | 341(21.50) | 225(24.89) | |||

| Distant | 2675 | 1456(42.19) | 296(43.15) | 563(35.50) | 360(39.82) | |||

| UNK Stage | 235 | 89(2.58) | 30(4.37) | 88(5.55) | 28(3.10) | |||

*Other includes American Indian/AK Native, Asian/Pacific Islander.

#Other includes squamous cell carcinoma/complex epithelial neoplasms/complex mixed and stromal neoplasms.

/ductal and lobular neoplasms.

Compared to married, divorced/separated and single patients with GBC, widowed group had higher proportion of women (89.16% VS 60.71%, 76.68% and 70.02%), more prevalence of elderly patients (96.09% VS 71.05%, 67.20% and 59.62%), higher percentage of AJCC stage I/II (57.38% VS 54.30%, 51.02% and 54.54%) and of SEER localized stage (37.45% VS 30.40%, 29.01% and 32.19%) All these differences were statistically significant (Table 1, P < 0.05).

Effect of marital status on CSS in the SEER database

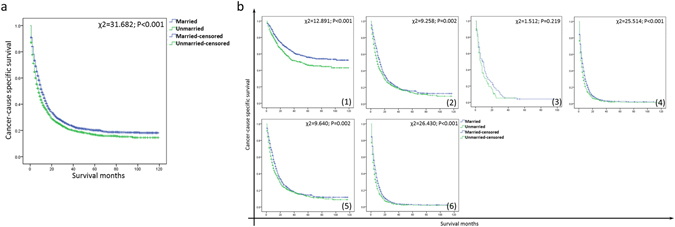

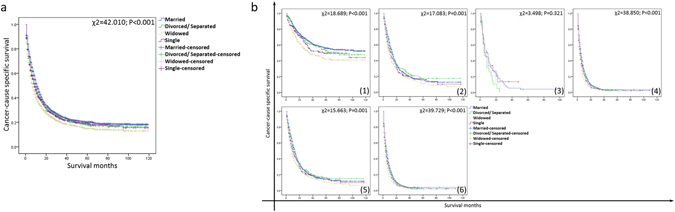

Married patients showed a higher 5-year CSS compared to unmarried patients (Fig. 1, 20.1% v.s. 17.8%, P < 0.001). Married group had higher survival rate in patients of TNM stage I, II and IV (stage I: χ2 = 12.891, P < 0.001; stage II: χ2 = 9.258, P = 0.002; stage IV: χ2 = 25.514, P < 0.001). This difference was not significant for stage III because of the small number of patients (stage III: χ2 = 1.512, P = 0.219). There were significant differences between married group and unmarried group of stage II + III patients (χ2 = 9.640, P = 0.002) and stage III + IV patients (χ2 = 26.430, P < 0.001). A shown in Fig. 2, the subgroup analysis of marital status (married, widowed, divorced/separated and single) confirmed these findings.

Figure 1.

Survival curves of married and unmarried GBC patients. (a) All stages: χ2 = 31.682, P < 0.001; (b) (1) stage I: χ2 = 12.891, P < 0.001; (2) stage II: χ2 = 9.258, P = 0.002; (3) stage III: χ2 = 1.512, P = 0.219; (4) stage IV: χ2 = 25.514, P < 0.001; (5) stage II + III: χ2 = 9.640, P = 0.002; (6) stage III + IV: χ2 = 26.430, P < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Survival curves of GBC patients with different marital status (married, divorced/separated, widowed and single). (a) All stages: χ2 = 42.010, P < 0.001; (b) (1) stage I: χ2 = 18.698, P < 0.001; (2) stage II: χ2 = 17.083, P = 0.001; (3) stage III: χ2 = 3.498, P = 0.321; (4) stage IV: χ2 = 38.850, P < 0.001; (5) stage II + III: χ2 = 15.663, P = 0.001; (6) stage III + IV: χ2 = 39.729, P < 0.001.

Married group had the highest 3-year and 5-year CSS (24.3% and 20.1%) compared to divorced/separated group (22.4% and 18.1%), single group (22.3% and 19.2%), and widowed group (19.1% and 14.9%, P < 0.05). While the CSS of the married group was higher than the single group (P < 0.05). Additionally, age, race, grade, histologic type, AJCC stage, SEER stage and marital status were identified as significant risk factors for the survival of GBC on univariate analysis (Table 2, P < 0.05). All these seven variables were independent prognostic factors in multivariate analysis of Cox regression (Table 2, P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate survival analysis for evaluating the influence of marital status on CSS of GBC patients in SEER database.

| Parameter | Characteristic | 3-year CCS | 5-year CCS | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log rank χ2 test | P | HR(95%CI) | P | ||||

| Sex | 3.011 | 0.083 | NI | ||||

| Male | 20.6% | 16.5% | |||||

| Female | 23.5% | 19.4% | |||||

| Age | 41.777 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| <60 | 27.0% | 23.2% | Reference | ||||

| ≥60 | 21.1% | 17.0% | 0.708(0.658–0.762) | ||||

| Race | 19.311 | 0.000 | 0.005 | ||||

| White | 23% | 18.7% | Reference | ||||

| Black | 17.2% | 14.7% | 3.259(1.234–8.795) | ||||

| *Others | 25% | 21.3% | 3.709(1.386–9.930) | ||||

| Unkown | 30.4% | 22.4% | 3.226(1.204–8.641) | ||||

| Grade | 753.005 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| Well differentiated | 52.4% | 44.9% | Reference | ||||

| Moderately differentiated | 32% | 25.9% | 0.552(0.481–0.633) | ||||

| Poorly differentiated | 15% | 11.7% | 0.672(0.617–0.732) | ||||

| Undifferentiated | 20.3% | 16.8% | 0.991(0.915–1.073) | ||||

| Unkown | 11.4% | 9.7% | 0.889(0.656–1.204) | ||||

| Histologic type | 131.039 | 0.000 | 0.004 | ||||

| Adenomas; adenocarcinomas | 24.3% | 19.8% | Reference | ||||

| Epithelial neoplasms | 16.3% | 15.1% | 0.768(0.666–0.885) | ||||

| Cystic, mucinous and serous neoplasms | 17.7% | 14.3% | 0.771(0.644–0.923) | ||||

| Unspecified neoplasms | 10.4% | 7.5% | 0.824(0.686–0.989) | ||||

| #Others | 14.6% | 12.6% | 0.873(0.680–1.122) | ||||

| AJCC Stage | 1891.004 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| I | 58.7% | 51.6% | Reference | ||||

| II | 20.6% | 14.8% | 0.384(0.318–0.464) | ||||

| III | 5.1% | 3.9% | 0.814(0.684–0.769) | ||||

| IV | 3.4% | 2.5% | 1.029(0.800–1.323) | ||||

| UNK Stage | 15% | 11.2% | 1.288(1.041–1.594) | ||||

| SEER | 1807.983 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| Localized | 52.7% | 45.4% | Reference | ||||

| Regional | 20.3% | 14.9% | 0.688(0.544–0.870) | ||||

| Distant | 3.7% | 2.9% | 0.895(0.708–1.132) | ||||

| UNK Stage | 10% | 4.6% | 1.198(0.922–1.557) | ||||

| Marital Status | 42.010 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| Married | 24.3% | 20.1% | Reference | ||||

| Divorced/ Separated | 22.4% | 18.1% | 0.864(0.787–0.948) | ||||

| Widowed | 19.1% | 14.9% | 0.942(0.832–1.065) | ||||

| Single | 22.3% | 19.2% | 1.087(0.928–1.208) | ||||

*Other includes American Indian/AK Native, Asian/Pacific Islander. #Other includes squamous cell carcinoma/complex epithelial neoplasms/complex mixed and stromal neoplasms/ductal and lobular neoplasms. NI: not included in the multivariate survival analysis.

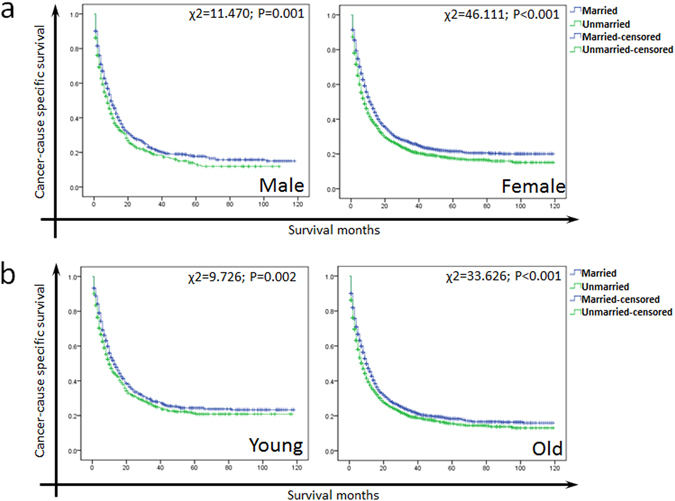

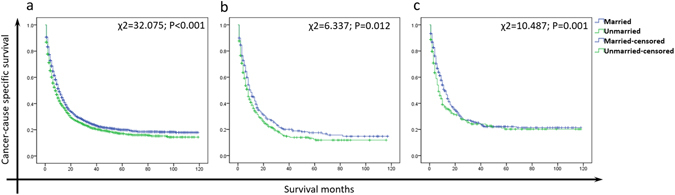

Effect of marital status on CSS stratified by gender, age and race

We further explored the effect of marital status on CSS stratified by gender, age and race. As shown in Fig. 3a, married ones had a better survival compared to unmarried in both males (χ2 = 11.470, P = 0.001) and females (χ2 = 46.111, P < 0.001). Compare to unmarried patients, married patients with different ages and races all had better survival (Fig. 3b and Fig. 4, P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

(a) The survival curves of male and female GBC patients with different marital status. (b) The survival survival curves of young and old GBC patients with different marital status.

Figure 4.

The survival curves of white (a), black (b) and other (c) GBC patients with different marital status. (c) American Indian/AK Native, Asian/Pacific Islander.

Subgroup analysis for evaluating the effect of marital status on each TNM stage

According to the univariate analysis, marital status was related to the survival of AJCC stage I (Table 3, χ2 = 18.689, P < 0.001), stage II (χ2 = 17.083, P = 0.001) and stage III + IV subgroups (χ2 = 39.729, P < 0.001). We also found that widowed patients had 14.0% less of 5-year CSS compared to married patients of stage I (55.9% VS 41.9%, P < 0.05), 14.7% of stage II (15.6% VS 10.9%, P < 0.05), and 1.5% of stage III + IV (2.9% VS 1.4%, P < 0.05). Single was an independent prognostic factor for stage III + IV patients (Table 3, HR = 1.225, 95%CI 1.054–1.423, P = 0.008).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of marital status on CSS of GBC patients based on TNM stage.

| Parameter | Characteristic | 3-year CCS | 5-year CCS | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log rank χ2 test | P value | HR(95%CI) | P value | ||||

| TNM Stage | |||||||

| Stage I | |||||||

| Marital Status | 18.689 | 0.000 | |||||

| Married | 63.5% | 55.9% | Reference | ||||

| Divorced/Separated | 61.0% | 52.8% | 0.802(0.622–1.034) | 0.089 | |||

| Widowed | 48.3% | 41.9% | 0.890(0.626–1.263) | 0.513 | |||

| Single | 54.3% | 49.5% | 1.224(0.930–1.611) | 0.148 | |||

| Stage II | |||||||

| Marital Status | 17.083 | 0.001 | |||||

| Married | 21.3% | 15.6% | Reference | ||||

| Divorced/ Separated | 23.9% | 17.4% | 0.870(0.735–1.030) | 0.105 | |||

| Widowed | 17.6% | 10.9% | 0.860(0.681–1.087) | 0.208 | |||

| Single | 20.6% | 17.0% | 1.132(0.938–1.365) | 0.196 | |||

| Stage III + IV | |||||||

| Marital Status | 39.729 | 0.000 | |||||

| Married | 3.7% | 2.9% | Reference | ||||

| Divorced/ Separated | 3.3% | 2% | 0.886(0.777–1.010) | 0.069 | |||

| Widowed | 2.3% | 1.4% | 0.996(0.840–1.182) | 0.965 | |||

| Single | 3.9% | 3.9% | 1.225(1.054–1.423) | 0.008 | |||

P-values refer to comparisons between two groups and were adjusted for age, race, grade and histologic type as covariates.

NI: not included in the multivariate survival analysis.

Discussion

Marital status has been found to be a prognostic factor for survival in various cancers. Mahdi et al. selected 49,777 patients with epithelial ovarian cancer from SEER database, and demonstrated that married patients had a better survival compared to unmarried patients with an overall 5-year survival 45.0% for married patients and 33.1% for unmarried patients16. Krongrad et al. reported that married patients with prostate cancer had a better survival single, divorced, separated or widowed ones17. In this study, we first reported that widowed patients were at high risk of cancer-specific mortality and marriage can be a protective prognostic factor in CSS.

Our finding showed that married group had higher survival rate in patients of TNM stage I, II and IV. Although this correlation between marriage and cancer was supported by previous studies18–22, the reasons were not fully understood. Unlike unmarried ones, married patients are more likely to receive standard treatments and social support. It has been reported that social support can increase 1-year survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer23, and mitigate the harmful physiologic effects of stress and restrain cancer progression through immunologic or neuroendocrine pathways24–26. In addition, marriage reflects better economic status, which can provide the better nursing and medical care27. Gomez et al. found that the differences in economic resources resulting in different survivals of cancer patients28. Also, healthy lifestyles have been shown among married population and married patients can have extra health care from spouses. Finally, married patients showed less distress, depression, and anxiety than unmarried counterparts29–31. Many neuroendocrine mediators and cytokines present in depression and stress were found to be related to cancer metastasis32, 33. In addition, marital status also affects the diagnosis and treatment of patients. It has been reported that married patients would have better prognosis because of diagnosis and treatment at the early stage34–36. As mentioned above, marriage is known as the most important social support. Lack of economic and psychological support provided by marriage may attribute to the poor survival outcomes in unmarried patients. Therefore, we suggest that more psychological care and social support are needed for unmarried patients with GBC, especially for who are diagnosed at late stage and without treatment.

We also found that old (age ≥ 60) and female patients had worse prognosis. It might because aging would impair immune response, increase oxidative stress, shorten telomeres, and cause accumulation of senescent cells37, 38. While elder females experienced the changes of estrogen and progesterone which are closely related to the progression of cancer39, 40.

This study has several potential limitations. First, the SEER database does not include therapeutic information such as radical resection, palliative therapy, and detailed information of chemotherapy, recurrence and metastasis, which may also impact the prognosis of GBC patients4. Second, information of education, economic, social status and quality of marriage is not provided by this database, which would also effect on the prognosis of patients12. Third, marital status is not followed up after diagnosis, which may not be the real marital status of patients.

In conclusion, we found that married GBC patients had a higher 5-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) than that of unmarried ones. Widowed patients were at a high risk of cancer-specific mortality and marriage can be a protective prognostic factor in CSS.

Method

Patients

Data was obtained from the SEER database. The current SEER database consists of 18 population-based cancer registries that represent approximately 26% of the population in the United States. The SEER data contain no identifiers and are publicly available for studies of cancer-based epidemiology and health policy.

The National Cancer Institute’s SEER*Stat software (Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software, www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat (Version 8.3.2) was used to identify patients who were pathologically diagnosed as GC between 2004 and 2013 with single primary GBC and a known marital status of age ≥ 18. Histological types were limited to adenomas adenocarcinomas, epithelial neoplasms, cystic, mucinous and serous neoplasms, and unspecified neoplasms and others (squamous cell carcinoma/complex epithelial neoplasms/complex mixed and stromal neoplasms/ductal and lobular neoplasms). Patients were excluded if they had multiple primary malignant neoplasm, with distant metastasis (M1), died within 30 days after surgery or unavailable information of CSS and survival months.

Statistical analysis

Clinicopathological parameters were analyzed by chi-square (χ2) test. Survival curves were generated using Kaplan-Meier estimates, and the differences were analyzed by log-rank test. Cox regression models were built for analyzing the risk factors of survival outcomes. Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package SPSS (version 19.0, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Results were considered to be statistically significant when a two-sided p values of less than 0.05.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by National Youth Science Foundation (81402002). The authors acknowledged the efforts of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER database. The interpretation and reporting of these data were the sole responsibility of the authors.

Author Contributions

X.X.L. and Y.L. planned the study. C.P.R. and Y.W. calculated statistics and analyzed the data. H.L.W. and X.W.L. wrote the manuscript. Y.P.S. and Z.Q.H. supervised the entire project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Xinxing Li, Ye Liu, Yi Wang and Canping Ruan contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yanping Sun, Email: sunyanping2003@163.com.

Zhiqian Hu, Email: huzhiq163@163.com.

References

- 1.Gourgiotis S, et al. Gallbladder cancer. Am J Surg. 2008;196:252–264. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Misra S, Chaturvedi A, Misra NC, Sharma ID. Carcinoma of the gallbladder. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:167–176. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(03)01021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kakaei F, Beheshtirouy S, Nejatollahi SM, Zarrintan S, Mafi MR. Surgical treatment of gallbladder carcinoma: a critical review. Updates Surg. 2015;67:339–351. doi: 10.1007/s13304-015-0328-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Q, Gan L, Liang L, Li X, Cai S. The influence of marital status on stage at diagnosis and survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:7339–7347. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin JJ, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with gastric cancer. Cancer medicine. 2016;5:1821–1829. doi: 10.1002/cam4.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi RL, et al. Marital status independently predicts gastric cancer survival after surgical resection–an analysis of the SEER database. Oncotarget. 2016;7:13228–13235. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang XD, et al. Marital status independently predicts pancreatic cancer survival in patients treated with surgical resection: an analysis of the SEER database. Oncotarget. 2016;7:24880–24887. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li, M. et al. Marital status is an independent prognostic factor for tracheal cancer patients: an analysis of the SEER database. Oncotarget (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Kaplan RM, Kronick RG. Marital status and longevity in the United States population. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2006;60:760–765. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.037606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu YR, Goldman N. Mortality differentials by marital status: an international comparison. Demography. 1990;27:233–250. doi: 10.2307/2061451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiu M, Yang D, Xu R. Impact of marital status on survival of gastric adenocarcinoma patients: Results from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Database. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21098. doi: 10.1038/srep21098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aizer AA, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3869–3876. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torssander J, Erikson R. Marital partner and mortality: the effects of the social positions of both spouses. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2009;63:992–998. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.089623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelles JL, Joseph SA, Konety BR. The impact of marriage on bladder cancer mortality. Urologic oncology. 2009;27:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Wilson SE, Stewart DB, Hollenbeak CS. Marital status and colon cancer outcomes in US Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results registries: does marriage affect cancer survival by gender and stage? Cancer epidemiology. 2011;35:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahdi H, et al. Prognostic impact of marital status on survival of women with epithelial ovarian cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2013;22:83–88. doi: 10.1002/pon.2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krongrad A, Lai H, Burke MA, Goodkin K, Lai S. Marriage and mortality in prostate cancer. J Urol. 1996;156:1696–1670. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)65485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klaassen Z, Reinstatler L, Terris MK, Underwood W, 3rd, Moses KA. Beyond biology: the impact of marital status on survival of patients with adrenocortical carcinoma. International braz j urol: official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology. 2015;41:1108–1115. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2014.0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLaughlin, J. M., Fisher, J. L. & Paskett, E. D. Marital status and stage at diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma: results from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program, 1973-2006. Cancer117, 1984-1993 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Osborne C, Ostir GV, Du X, Peek MK, Goodwin JS. The influence of marital status on the stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival of older women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;93:41–47. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-3702-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Datta GD, Neville BA, Kawachi I, Datta NS, Earle CC. Marital status and survival following bladder cancer. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2009;63:807–813. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.082438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reyes Ortiz CA, Freeman JL, Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. The influence of marital status on stage at diagnosis and survival of older persons with melanoma. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2007;62:892–898. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.8.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mustafa, M., Carson-Stevens, A., Gillespie, D. & Edwards, A. G. Psychological interventions for women with metastatic breast cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, CD004253 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Manzoli L, Villari P, G. MP, Boccia A. Marital status and mortality in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Social science & medicine. 2007;64:77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rendall MS, Weden MM, Favreault MM, Waldron H. The protective effect of marriage for survival: a review and update. Demography. 2011;48:481–506. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spiegel D, Sephton SE, Terr AI, Stites DP. Effects of psychosocial treatment in prolonging cancer survival may be mediated by neuroimmune pathways. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;840:674–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aizer AA, et al. Multidisciplinary care and pursuit of active surveillance in low-risk prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3071–3076. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez SL, et al. Effects of marital status and economic resources on survival after cancer: A population-based study. Cancer. 2016;122:1618–1625. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldzweig G, et al. Psychological distress among male patients and male spouses: what do oncologists need to know? Ann Oncol. 2010;21:877–883. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallo LC, Troxel WM, Matthews KA, Kuller LH. Marital status and quality in middle-aged women: Associations with levels and trajectories of cardiovascular risk factors. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2003;22:453–463. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferrara N, Davis-Smyth T. The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocrine reviews. 1997;18:4–25. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.1.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moreno-Smith M, Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK. Impact of stress on cancer metastasis. Future Oncol. 2010;6:1863–1881. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodwin JS, Zhang DD, Ostir GV. Effect of depression on diagnosis, treatment, and survival of older women with breast cancer. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:106–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterson EB, et al. Impact of provider-patient communication on cancer screening adherence: A systematic review. Preventive medicine. 2016;93:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doherty, M. K. & Knox, J. J. Adjuvant therapy for resected biliary tract cancer: a review. Chinese clinical oncology (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Yabar CS, Winter JM. Pancreatic Cancer: A Review. Gastroenterology clinics of North America. 2016;45:429–445. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fulop T, Larbi A, Kotb R, de Angelis F, Pawelec G. Aging, immunity, and cancer. Discovery medicine. 2011;11:537–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoeijmakers JH. DNA damage, aging, and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1475–1485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Del Pup L, et al. Endocrine disruptors and female cancer: Informing the patients (Review) Oncology reports. 2015;34:3–11. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rachon D. Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and female cancer: Informing the patients. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders. 2015;16:359–364. doi: 10.1007/s11154-016-9332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]