Abstract

Recent studies indicate that serum alkaline phosphatase (AlkPhos), a surrogate of high turnover bone disease, is associated with coronary artery calcification and death risk in maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) patients. The association between AlkPhos and bone mineral density (BMD) is not well studied. We studied the association between AlkPhos and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry-assessed BMD in a group of MHD patients in Southern California. In 154 MHD patients, aged 55.3 +/- 13.6 years, including 42% women, 38% Hispanics, 42% African Americans, and 55% diabetics, the mean serum AlkPhos was 121 +/- 63 U/L (median: 101, Q(25-75): 81-141); 36% had AlkPhos>/=120 U/L and 50% had a total T-score< or =-1. Whereas the total BMD did not correlate with age (r=0.01, P=0.99) or body mass index (r=0.10, P=0.22), it correlated negatively with AlkPhos (r=-0.25, P=0.002), including after multivariate adjustment (r=-0.24, P=0.003). The proportion of patients with a high coronary artery calcification score>400 was incrementally higher across worsening BMD tertiles (P trend=0.04). The BMD was significantly worse in MHD patients with serum AlkPhos> or =120 U/L compared with <120 U/L (1.01 +/- 0.016 vs. 1.08 +/- 0.013 g/cm(2), respectively, P<0.001). The multivariate adjusted odds ratio of AlkPhos> or =120 U/L for having a total T-score<-1.0 was 2.3 (1.1-4.8, P=0.037). Among routine clinical and biochemical markers, serum AlkPhos> or =120 U/L was a better predictor of total T-score< or =-1 in MHD patients. An association exists between higher serum AlkPhos and worse dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry-assessed BMD in MHD patients. Given these findings, studies are indicated to examine whether interventions that lower serum AlkPhos improve BMD in MHD patients..

Keywords: Alkaline phosphatase, bone mineral density, DEXA, cytokines, chronic kidney disease, hemodialysis

Introduction

Renal osteodystrophy and other metabolic bone diseases are common in individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) including patient undergoing maintenance hemodialysis (MHD).1-3 In the general population, such demographic and biological features as age, gender and sexual hormones, and body mass index (BMI) are the most significant determinants of bone mineral density (BMD); however, the abnormalities of bone turnover and bone metabolism in CKD patients, due to mineral abnormalities, hyperparathyroidism, and disorders of vitamin D metabolism, may change the traditional determinants of BMD in CKD patients.

Serum alkaline phosphatase (AlkPhos), a marker of osteoblastic activity, has been recently shown to be associated with coronary artery calcification in CKD patients.[**] 4-9 Moreover, two recent epidemiologic studies have shown an associations between higher serum AlkPhos and poor survival including increased cardiovascular death in MHD patients.4, 5 Blayney et al reported the association between AlkPhos and increased fracture rate in MHD patients, leading to increased hospitalization.5 An increase in serum AlkPhos, also known as hyperphosphatasemia or hyperphosphatasia (not to confuse with hyperphosphatemia), commonly occurs in CKD patients with high turnover bone disease,10 usually from excesses of the bone isoforms of the enzyme, esp. in the absence of liver disorders.11, 12

Although the distorted bone and mineral metabolism in MHD patient has been widely studied, the risk factors and predictors of decreased BMD in MHD patients are not well understood.13, 14 Given the observed association between serum AlkPhos and fracture in recent studies,5, 13 we hypothesized that the increased serum AlkPhos may be a marker of decreased BMD in MHD patients. To test this hypothesis we examined the association of serum AlkPhos and BMD in a cohort of MHD patients in whom other potential correlates of renal osteodystrophy and metabolic disorders including serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) and nutritional and inflammatory markers were also examined.

Methods

Patient Population

We studied a randomly selected group of MHD patients who participated in the substudy of the Nutritional and Inflammatory Evaluation in Dialysis (NIED) Study (see the NIED Study website at www.NIEDStudy.org for more details, as well as previous publications).40-43 [**] The original patient cohort was derived from a pool of more than 3,000 MHD outpatients over 5 years in eight DaVita chronic dialysis facilities in the South Bay Los Angeles area. Inclusion criteria were outpatients who had been undergoing MHD for at least eight weeks, who were 18 years or older and who signed the Institutional Review Board approved consent form. Patients with an anticipated life expectancy of less than 6 months (e.g. due to a metastatic malignancy or advanced HIV/AIDS disease) were excluded. From October 1, 2001, through December 31, 2006, 893 MHD patients signed the informed consent form and underwent the periodic evaluations of the NIED Study and 176 of these individuals were randomly invited to undergo additional tests at the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) at Harbor-UCLA as parts of the “NIED Substudy”.41

Bone Densitometry Assessment

Out of the said substudy, 154 patients had both measured serum AlkPhos and BMD assessment by dual energy X ray absorptiometry (DEXA), expressed in grams per cm2 using the DEXA scan Hologic fan-beam QDR-4500-Delphi-A (Software: QDR for Windows XP version 12.4.Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total BMD was measured from vertex to toe (i.e. whole body BMD). The device normative data of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) were used as reference values to calculate the total T-score.

Coronary Artery Calcificatuon Scoring

All subjects underwent electron beam computerized tomography (EBCT) to assess coronary artery calcification score (CACS) using an Imatron C-150XL ultrafast computed tomography scanner (GE-Imatron, South San Francisco, California) immediately after the DEXA scanning in Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA, St. John's Cardiovascular Center as described previously.47 [**]

Anthropometric and Dietary Measures

Body weight assessment and anthropometric measurements were performed while patients underwent a hemodialysis treatment or within 5 to 20 minutes after termination of the treatment. Biceps skinfold (BSF) and triceps skinfold (TSF) thicknesses were measured with a conventional skinfold caliper using standard techniques as previously described.48, 49 Three-day diet recall with a subsequent interview was performed to estimate the total daily protein and calorie intake.50

Near Infra-Red Interactance

To estimate the percentage of body fat and fat-free body mass, near infra-red (NIR) interactance was measured at the same time as the anthropometric measurements.51 A commercial near-infrared interactance sensor with a coefficient of variation of 0.5% for total body fat measurement (portable Futrex 6100®, Gaithersburg, Maryland, www.futrex.com) was used. NIR measurements were performed by placing, for several seconds on the upper aspect of the arm without a vascular access, a Futrex® sensor, and entering the required data (date of birth, gender, weight and height) of each patient. NIR measurements of body fat appear to correlate significantly with other nutritional measures in MHD patients.52

Laboratory Tests

Pre-dialysis blood samples and post-dialysis serum urea nitrogen were obtained on a mid-week day which coincided chronologically with the drawing of quarterly blood tests in the DaVita facilities. The single-pool Kt/V was used to represent the weekly dialysis dose. All routine laboratory measurements were performed by DaVita® Laboratories (Deland, FL) using automated methods. Roche modular instrumentation method53 (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN), was used for quantitative determinations of AlkPhos, in that p-nitrophenyl phosphate is converted to p-nitrophenol plus phosphate, where p-nitrophenol released is proportional to the AlkPhos activity and is measured photometrically. Measured imprecision studies using DaVita patient samples recovered a coefficient of variation of <2.0% and an extended reportable range of 1.0 to 4,400 U/L (personal communication with Dr. J. Steinmetz at DaVita® Laboratories).

Serum high sensitivity CRP was measured by a turbidometric immunoassay in which a serum sample is mixed with latex beads coated with anti-human CRP antibodies forming an insoluble aggregate (manufacturer: WPCI, Osaka, Japan, unit: mg/L, normal range: <3.0 mg/L).54, 55 IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) were measured with immunoassay kits based on a solid phase sandwich ELISA using recombinant human IL-6 and TNF-α (manufacturer: R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; units: pg/ml; normal range: IL-6: <9.9 pg/ml, TNF-α: <4.7 pg/ml).56, 57 CRP, TNF-alpha, IL-1 and IL-6 were measured in the General Clinical Research Center Laboratories of Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. Serum transthyretin (prealbumin) was measured using immunoprecipitin analysis. Plasma total homocysteine concentrations were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography in the Harbor-UCLA Clinical Laboratories.

Other Assessments

The medical chart of each MHD patient was thoroughly reviewed by a collaborating physician, and data pertaining to the underlying kidney disease, cardiovascular history and other comorbid conditions were extracted. A modified version of the Charlson comorbidity index, i.e., without the age and kidney disease components, was used to assess the severity of comorbidities.45, 46

Statistical Methods

Pearson correlation coefficient was employed to examine the crude and adjusted linear correlation between total BMD and AlkPhos as well as other relevant variables. Multivariate logistic regression models were fitted to construct odds ratio (OR) of decreased bone density (i.e. T-score <-1.0) in patients with AlkPhos ≥120 U/L before and after controlling for confounding covariates. Restricted cubic spline graphs were utilized as exploratory data analyses to illustrate systematic relations between serum AlkPhos and BMD and T-score <-1.0. This method also served to examine the non-linear associations of continuous serum AlkPhos as an alternative to inappropriate linearity assumptions.58 Fiducial limits are given as mean±SD (standard deviation); OR values include 95% confidence interval (CI) levels. A p-value <0.05 or a 95% CI that did not span 1.0 was considered to be statistically significant. A p-value between 0.05 and 0.10 was considered to indicate a trend in order to mitigate the chance of Type II error, i.e., accepting the null hypothesis when it should be rejected. Descriptive and multivariate statistics were carried out with the statistical software “Stata version 10.0” (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

Results

The 154 subjects of the study were 55.3±13.6 years old (mean ±SD) and included 42% women, 38% Hispanic, 42% African-American and 55% diabetic patients. The mean dialysis vintage was 41±34 months (median: 32, inter-quartile range: 16-59 months). The mean serum AlkPhos was 121±63 U/L (median: 101, percentile 25%-75%: 81-141); 36% of patients had AlkPhos ≥120 (U/L) and 50% had a total T-score ≤-1.

Table 1 shows the relevant demographic, clinical and laboratory measures across the three almost equally sized tertiles of total T-score (<-1.6, -1.6 to 0.2, and ≤0.2) with 47 to 55 subjects in each tertile. Age, dialysis vintage and serum AlkPhos were higher in patients in the lowest T-score tertile. The proportion of women was higher in the lower T-score tertiles, but the trend did not reach statistically significant level (p trend=0.11). Both the mean (or median) serum AlkPhos and the proportion of patients with serum AlkPhos ≥120 U/L were higher across worsening T-score tertile (p trend of 0.008 and 0.004, respectively). The proportion of patients with a high CACS >400 was incrementally higher across worsening BMD tertiles (p trend=0.04). There was no difference across the tertiles in terms of race/ethnicity, body mass index, serum calcium, phosphorus and their product, intact PTH, and the prescribed paricalcitol dose. But patients in the poorer t-score tertile tended to have higher body fat measured by near infrared method (p trend=0.08). Serum C-reactive protein level showed a decreasing trend across T-score tertiles (p trend=0.06) but there was no trend for serum interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha across the T-score tertiles.

Table 1. Baseline demographic, clinical, and laboratory variables according to the tertiles of T score 154 maintenance HD patients1.

| Variable | Tertiles of total T Score | P trend | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| First tertile (lowest BMD) |

Second tertile | Third tertile (highest BMD) |

||

|

| ||||

| < -1.6 (n=52) |

-1.6 to < -0.2 (n=55) |

≥ -0.2 (n=47) |

||

| Demographic | ||||

| Age (years) | 57±14 | 54±13 | 53±13 | <0.001 |

| Women (%) | 50 | 40 | 34 | 0.11 |

| Race: % African-American | 37 | 38 | 53 | 0.10 |

| Ethnicity: % Hispanic | 42 | 44 | 28 | 0.14 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 44 | 53 | 36 | 0.45 |

| Body composition, nutritional and physical evaluations | ||||

| Total proteins | 60.8±25.0 | 65.7±28.3 | 77.0±26.9 | 0.32 |

| Total Calories | 1524±574 | 1593±621 | 1851±667 | 0.39 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.8±5.2 | 25.9±4.9 | 26.4±6.7 | 0.57 |

| Triceps skinfold (mm) | 14.9±6.8 | 17.3±9.6 | 15.0±8.3 | 0.94 |

| Biceps skinfold (mm) | 9.6±6.5 | 9.7±5.4 | 8.9±7.2 | 0.58 |

| Near infrared measured body fat (%) | 27.6±9.3 | 25.5±9.6 | 23.8±11.7 | 0.08 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm-Hg) | 156±24 | 147±25 | 147±24 | 0.09 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm-Hg) | 77±14 | 78±16 | 77±16 | 0.88 |

| Hemodialysis treatment measures | ||||

| Dialysis vintage <6 months (%) | 8 | 10 | 15 | 0.26 |

| Dialysis vintage (months) | 45.1±37.5 | 44.4±35.0 | 32.2±27.9 | 0.03 |

| Dialysis dose (Kt/V single pool) | 1.76±0.25 | 1.72±0.32 | 1.65±0.24 | 0.06 |

| nPNA or nPCR (g.kg-1.day-1) | 1.06±0.22 | 1.10±0.22 | 1.05±0.21 | 0.87 |

| Erythropoietin dose (1,000 u/week) | 12.9±12.5 | 11.1±8.2 | 11.6±7.8 | 0.99 |

| Paricalcitol dose (mg/month) | 60±83 | 39±26 | 49±37 | 0.35 |

| Biochemical measurements | ||||

| Albumin (g/dl) | 4.00±0.26 | 3.98±0.33 | 3.99±0.24 | 0.96 |

| transthyretin (prealbumin) (mg/dl) | 27.7±8.6 | 30.9±8.9 | 30.1±9.7 | 0.20 |

| triglycerides (mg/dl) | 132±95 | 144±88 | 169±162 | 0.13 |

| total cholesterols (mg/dl) | 143±36 | 147±40 | 155±47 | 0.14 |

| low density lipoprotein-C (mg/dl) | 78±23 | 78±34 | 88±32 | 0.12 |

| high density lipoprotein-C (mg/dl) | 38±16 | 38±17 | 34±9 | 0.20 |

| creatinine (mg/dl) | 10.0±2.6 | 10.8±2.8 | 10.8±3.0 | 0.16 |

| ferritin (ng/ml) | 728±467 | 489±381 | 616±465 | 0.25 |

| iron saturation ratio (%) | 36.9±12.9 | 33.3±10.7 | 35.1±10.3 | 0.41 |

| total iron binding capacity (mg/dl) | 204±40 | 216±38 | 210±30 | 0.44 |

| calcium (mg/dl) | 9.5±0.6 | 9.6±0.8 | 9.7±0.6 | 0.16 |

| phosphorus (mg/dl) | 5.6±1.3 | 5.5±1.3 | 5.6±1.2 | 0.95 |

| calcium X phosphorus | 53.5±11.9 | 52.7±12.2 | 54.6±11.9 | 0.66 |

| intact PTH (pg/ml) | 284±204 | 246±153 | 318±368 | 0.52 |

| alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 140±72 | 115±55 | 107±58 | 0.008 |

| alkaline phos, median +/- IQR | 117±58 | 90±58 | 89±45 | N/A |

| alkaline phosphatase ≥120 (U/L) % | 49 | 35 | 21 | 0.004 |

| serum AST (SGOT) (IU/L) | 20.3±17.6 | 18.7±9.25 | 17.9±11.0 | 0.36 |

| bicarbonate (mg/dl) | 22.4±2.9 | 22.3±3.2 | 22.3±2.7 | 0.70 |

| total homocysteine (μmol/l) | 27.2±8.0 | 25.3±7.3 | 26.6±10.8 | 0.71 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 3.6±3.7 | 5.0±5.2 | 5.6±6.3 | 0.06 |

| interleukin-6 (pg/ml) | 10.4±9.3 | 8.2±6.5 | 21.5±90.1 | 0.47 |

| Tumor necrosis factor-α (pg/ml) | 5.8±3.8 | 5.5±6.7 | 7.8±10.7 | 0.35 |

| Blood hemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.1±0.8 | 12.2±0.7 | 12.4±0.7 | 0.04 |

| WBC (×1000 cell/μl) | 6.7±1.5 | 6.7±1.7 | 6.8±2.1 | 0.89 |

| lymphocyte (% of total WBC) | 24.0±7.3 | 25.0±7.4 | 24.9±7.8 | 0.56 |

| Coronary Artery Calcification Score (CACS) | ||||

| Total score | 1511±2947 | 725±946 | 869±1518 | 0.12 |

| CACS ≥400 (%) | 56 | 47 | 35 | 0.04 |

Kt/V, dialysis dose; nPCR, normalized protein catabolic rate

All values are presented as Mean ± SD or percentages

P-values for dialysis dose (vintage), Erythropoietin dose, ferritin, CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α are based on the logarithmic values of these measures.

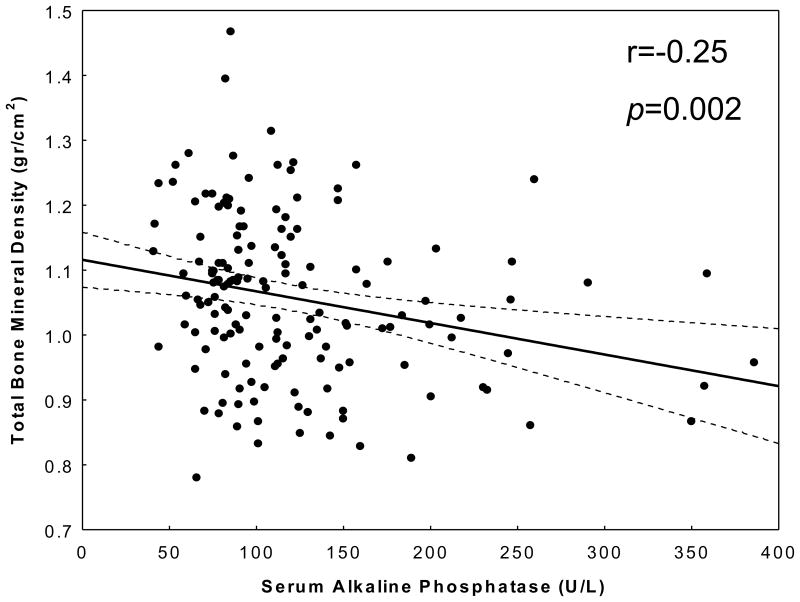

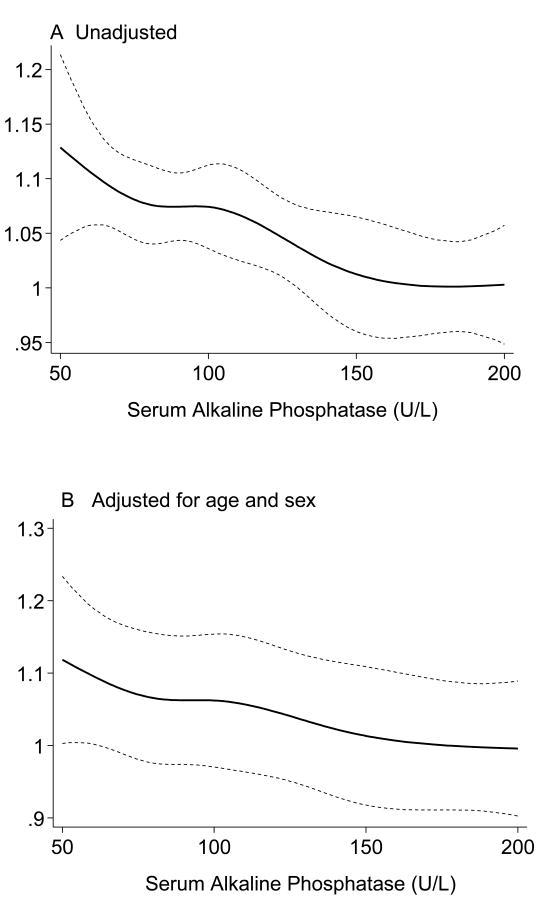

Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients between total BMD and some relevant nutritional, inflammatory and other biochemical variables. In addition to unadjusted (Pearson) correlation coefficients, multivariate adjusted correlations using linear regression models have also been calculated in order to disclose the underlying associations after removing the effect of confounders. Dialysis vintage was negatively correlated with total BMD, but the correlation mitigated after adjustment for age, sex, diabetes, and liver enzymes aspartate transaminase (AST). Dietary protein and calorie intake and serum CRP were positively correlated with total BMD including after adjustment for other confounders. Serum AlkPhos exhibited the highest correlatation coefficient with the total BMD (r=-0.25, p=0.002) even after controlling for other confounders (adjusted r=-0.24, p=0.0.003) (Figure 1). Figure 2 illustrates the aforementioned trend between serum AlkPhos and total BMD depicted using regression spline models.

Table 2. Bivariate (unadjusted) and partial (adjusted) correlation coefficients between total bone mineral density and relevant variables in 154 maintenance HD patients.

| Variable | Bivariate correlation | P | Adjusted correlation | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.01 | 0.99 | -0.11 | 0.19 |

| Dialysis vintage (log scale) | -0.16 | 0.05 | -0.11 | 0.18 |

| Body mass index | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| NIR body fat percentage | -0.17 | 0.35 | -0.01 | 0.96 |

| Dietary protein intake | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.09 |

| Dietary energy (calorie) intake | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.05 |

| Serum calcium | 0.02 | 0.78 | 0.09 | 0.29 |

| phosphorous | -0.03 | 0.76 | 0.02 | 0.84 |

| Calcium X phosphorous | -0.01 | 0.88 | 0.05 | 0.53 |

| intact PTH (log scale) | -0.08 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.70 |

| alkaline phosphatase | -0.25 | 0.002 | -0.24 | 0.003 |

| AST (Log scale) | -0.02 | 0.79 | -0.04 | 0.60 |

| albumin | -0.01 | 0.97 | -0.08 | 0.34 |

| transthyretin | 0.07 | 0.39 | 0.10 | 0.27 |

| TIBC | 0.09 | 0.30 | 0.03 | 0.68 |

| ferritin | -0.09 | 0.25 | -0.05 | 0.54 |

| interleukin-6 (log scale) | 0.02 | 0.84 | 0.01 | 0.90 |

| TNF-a (log scale) | 0.05 | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.56 |

| CRP | +0.19 | 0.02 | +0.17 | 0.04 |

TIBC, total iron binding capacity; PTH, parathyroid hormone; AST (Aspartat aminotransferase)

In the adjusted analysis, age, sex, diabetes, AST, and Log vintage were included as covariate.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot, regression line and 95% confidence intervals, reflecting the correlation between serum alkaline phosphatase and total bone mineral density.

Figure 2.

Regression spline models of association between serum alkaline phosphatase and total bone mineral density in 154 maintenance hemodialysis patients.

Panel A: Unadjusted

Panel B: Adjusted for age and sex

In order to further examine the association of serum AlkPhos with total BMD, additional multivariate regression analysis were conducted as shown in Table 3. In addition to conventional correlates of decreased BMD including age, sex, dialysis vintage and diabetes mellitus, serum AlkPhos was the only biochemical marker with strong association with total BMD especially after multivariate adjustment. This association persisted even after adjustment for serum calcium, phosphorus or their product (data not shown).

Table 3. Multiple regression models to predict total bone mineral density (gr/cm2) in 154 maintenance hemodialysis patients.

| β ± SE | Standardized regression coefficient | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | |||

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | -0.0005±0.0002 | -0.246 | 0.002 |

| Adjusted | |||

| Age (years) | -0.001±0.0008 | -0.135 | 0.12 |

| Sex (male) | 0.065±0.020 | 0.255 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.054±0.023 | 0.212 | 0.022 |

| Log vintage (months) | -0.013±0.01 | -0.112 | 0.17 |

| Log SGOT (IU/l) | 0.0097±0.022 | 0.036 | 0.66 |

| Log intact PTH (pg/ml) | -0.017±0.016 | 0.095 | 0.29 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | -0.0005±0.0002 | -0.257 | 0.002 |

SE: Standard error

In order to further examine the association between high AlkPhos and risk of decreased BMD, we dichotomized AlkPhos at 120 U/L as recently suggested in two recent studies as the cutoff value above which death risk and risk coronary artery calcification score are increased.4 [**] Total BMD was significantly lower in MHD patients with serum AlkPhos ≥120 U/L compared to <120 U/L (1.01±0.016 g/cm2 vs. 1.08±0.013, respectively, p<0.001). This trend was persistent within different sites of BMD measurements (data not shown).

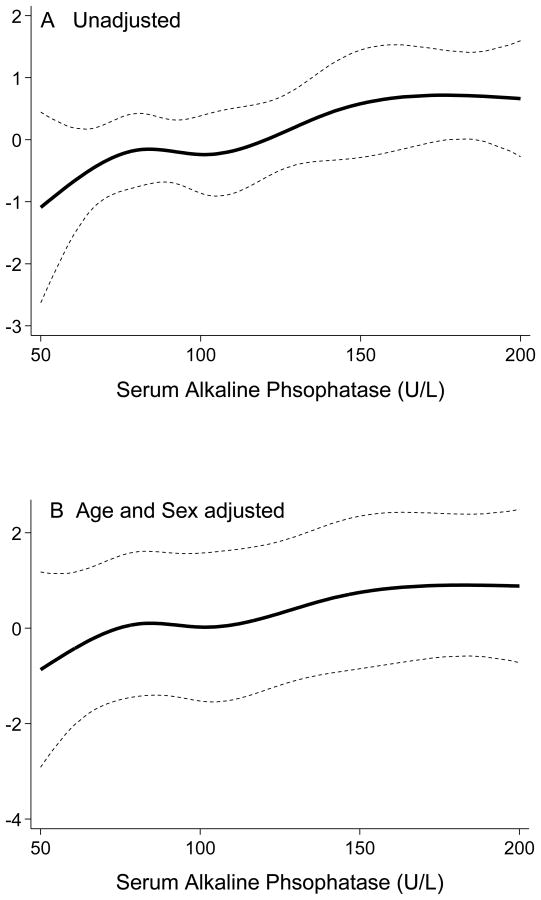

Using continuous cubic splines analyses to explore the non-linear association between total BMD and serum AlkPhos, we examined the odds of having a T-score <-1.0. As shown in Figure 3, the likelihood of having total T-score <-1.0 increased continuously with increasing levels of serum AlkPhos. Table 4 shows the results of unadjusted and multivariate adjusted logistic regression analyses for predicting T-score <-1.0 as the dependent variable. The unadjusted OR of having T-score <-1.0 in MHD patients with AlkPhos ≥120 U/L was 2.3 (95% CI: 1.2–4.5, p=0.019). The OR remained significant after multivariate adjustment for other relevant confounders. Indeed, in fully adjusted model including for demographics, diabetes, vintage, serum calcium, phosphorus, AST, and iPTH, having AlkPhos ≥120 U/L was associated with 2.3 times higher likelihood of total T-score <-1.0 compared to the lowest AlkPhos group (<120 U/L), i.e., an OR of 2.3 (95% CI: 1.1-4.8, p=0.037). Further sensitivity analyses using BMD measured in different sites such as right and left arms, right and left legs and thoracic spine showed similar findings (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Estimated log odds ratio of having T-score <-1 for continuous serum alkaline phosphatase in regression spline models in 154 maintenance hemodialysis patients

Panel A: Unadjusted

Panel B: Adjusted for age and sex

Table 4.

Unadjusted and multilevel adjusted odds ratios (and 95% confidence interval) of having T-score ≤-1.0 in maintenance HD patients with serum alkaline phosphatase ≥120 U/L.

| Serum alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| <120 (n=98) | ≥120 (n=54) | P | |

| Patients with T-score ≤-1.0 (%) | 43% (n=42) | 63% (n=34) | |

|

| |||

| Unadjusted odds ratios | reference | 2.27 (1.15-4.48) | 0.019 |

| Adjusted odds ratios, adjusted for: | |||

| Age | reference | 2.27 (1.15-4.48) | 0.019 |

| age + sex | reference | 2.11 (1.05-4.24) | 0.035 |

| age + sex + DM | reference | 2.17 (1.08-4.38) | 0.030 |

| age + sex + DM + Vintage | reference | 2.07 (1.01-4.26) | 0.048 |

| age + sex + DM + Vintage + calcium + phosphorus + SGOT + iPTH | reference | 2.25 (1.05-4.81) | 0.037 |

DM, diabetes mellitus; SGOT, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (aspartat aminotransferase)

Log transformed value of dialysis vintage, iPTH, and SGOT were used in these analyses.

Discussion

Among biochemical and clinical markers of bone and mineral disorders, we found that serum AlkPhos is the only measure with a statistically significant association with BMD in 154 randomly selected MHD patients. Other biochemical markers had either no association with BMD or their associations were mitigated after multivariate adjustment, whereas the association between AlkPhos and BMD was persistent even after adjustment for known confounders. Serum AlkPhos ≥120 U/L was a significant predictor of decreased BMD and particularly associated with the likelihood of T-score <-1.0.

Mineral and bone disorders occur frequently in CKD and are predictors of morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing maintenance dialysis treatment.1-3 The nature of bone disorders in CKD patients is more complex than in the general population, since CKD patients usually suffer from concomitant abnormalities in minerals, parathyroid hormone, vitamin D and fibroblast-growth factor-23 (FGF-23).15 [**] Furthermore, vascular calcification in CKD patients may be related to the bone and mineral disorders.9, 16-22 Hence, traditional determinants of BMD in CKD patients may be significantly different than in the general population in whom such demographic variables as age, sex and BMI or hormonal factors such as sexual hormones play a major role.

AlkPhos exists in bone, liver and placenta and is generally considered a marker of bone turnover in the setting of normal liver function.10, 12 Circulating level of AlkPhos increases as a result of high osteoclastic activity.10 Hence, a high serum AlkPhos level in CKD patients is usually from excesses of the bone isoforms of the enzyme.11, 12 Recent studies by Lomashvili et al7-9 have indicted a link between coronary artery calcification and tissue nonspecific AlkPhos. Several recent observational studies have shown consistent associations between higher serum AlkPhos and increased all-cause and cardiovascular death risk in MHD patients.4-9 In this study, we found a consistent association between serum AlkPhos and BMD that was robust to multivariate adjustment. Several studies in the past had shown that BMD may be associated with serum PTH or vitamin D level in CKD patients.3, 23-26 In our study, there was no association between mineral concentrations, PTH and other laboratory values and BMD. AlKPhos was the only measure with a significant association with the BMD.

In our study serum AlkPhos ≥120 U/L was a significant predictor of decreased BMD and associated with the likelihood of T-score <-1.0. A recent large epidemiologic study showed that AlkPhos ≥120 U/L was consistently associated with increased all-cause and cardiovascular death risk among different subgroups of MHD patients.4 Whereas the association between AlkPhos and death risk may be to the above-mentioned effect of AlkPhos on vascular calcification,9 the found AlkPhos-BMD link in our study may be another plausible explanation to that end, especially, since disorders of bone disease are known to be associated with increased death risk in both the general population27-29 and dialysis patients.30-32

Advanced age is known as the strongest correlate of decreased BMD.1, 33 In our study, however, age was not correlated with BMD. First, this may be due to limited number of young adults (i.e. those with peak bone mass) in our study population compared to the studies from the general population. A lowe prevalence of CKD in young adults may explain this age discrepancy. The second explanation is that the process of ageing is strongly associated with extraskeletal calcification in CKD patients, an important factor that might confound the validity of DEXA-measured BMD in CKD patients. Hence, some patients with advanced age may show paradoxically higher DEXA-measured BMD due to overlapping extraskeletal calcifications at BMD measurement sites, a confounding effect that may attenuate the inverse correlation of age and BMD. However, in the analyses, we utilized total BMD, instead of lumbar spine, to reduce the effect of this confounder. In addition, sensitivity analyses in upper extremities with limited extraskeletal calcification, also, did not show any unadjusted correlation between age and BMD (data not shown). The third explanation for why age was not correlated with BMD may be the higher risk of secondary hyperparathyroidism in prevalent hemodialysis patients. Indeed, BMD was inversely correlated with age after adjustment for iPTH and dialysis vintage and other confounders. This may highlight the role of extraskeletal calcification in measurement errors in BMD among CKD individuals.

The significance of low BMD is not quite clear in CKD patients. Indeed, there are no convincing data that support the definition of osteoporosis in patients with CKD.33 The term osteoporosis was originally defined as “a skeletal disorder characterized by compromised bone strength predisposing to an increased risk of fracture.”33 However, it is not clear whether a low BMD is associated with increased fracture risk in CKD patients and the reports in this field are very limited and inconsistent.34, 35 In this study, we used total T-score <-1.0 as the indicator of “low bone density;” however, at the present time, there is no accepted definition for low BMD in CKD patients.33

In addition to the lack of definition for “low BMD” in CKD patients, the role of DEXA as a diagnostic tool in advanced stages of CKD is unclear, as well. While low BMD is common in CKD,36, 37 studies examining its association with histologic subtypes of CKD-related bone disease19, 38 and fracture rates34, 35 in dialysis have shown inconsistent results, possibly because the more complex nature of bone disease in CKD is not fully reflected by merely a decrease in BMD. Lower BMD has, however, been associated with higher mortality in a single small study of dialysis patients,39 suggesting that the consequences of low BMD may be more far-reaching and may extend beyond bone-related events. One potential reason for the increased mortality seen with low BMD could be the biochemical changes associated with it, such as the higher alkaline phosphatase seen in our study. There have been no attempts thus far to study prospectively if treatment of low BMD and any associated biochemical abnormality could result in improved survival.

Our study should be qualified for a number of limitations including selection bias during enrollment leading to younger MHD patients. This may explain why age was not a significant predictor of BMD in our patients. Another limitation of our study is that we did not have bone biopsy specimens to determine histologic assessment of osteodystrophy. Moreover, we used DEXA to estimate the total and site-specific BMD. DEXA is the routine instrument in daily clinical practice, and so, our findings may have implication in routine clinical care; however, we did not measured BMD by quantitative computed tomography scanning. The strengths of our study include the moderate sample size, the comprehensive clinical and laboratory evaluations including body composition measures, detailed evaluation of comorbid states by study physicians, and measuring pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Conclusions

In our study, serum AlkPhos was the only biochemical measure with independent association with BMD in 154 randomly selected MHD patients. Serum AlkPhos ≥120 U/L was associated with the likelihood of low BMD (i.e. total T-score <-1.0). Our findings may have clinical implications in the diagnosis and treatment of CKD-MBD.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful Dr. Victor Goh, at Harbor-UCLA GCRC Core Laboratories for the management of blood samples and measuring inflammatory markers and to Mr. Chris Rucker and Beth Bennett from DaVita Clinical Research

Funding Sources: This study was supported by a research grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disease grant # DK61162 (for KKZ), a research grant from DaVita, Inc (KKZ), and a General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) grant # M01-RR00425 from the National Centers for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Potential Conflict of Interests: KKZ, CPK, ARN, and SMS have received grants and/or honoraria from Amgen, Abbott, Genzyme, Fresenius and Shire.

References

- 1.Moe S, Drueke T, Cunningham J, Goodman W, Martin K, Olgaard K, Ott S, Sprague S, Lameire N, Eknoyan G. Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Kidney Int. 2006;69:1945–1953. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moe SM, Drueke T, Lameire N, Eknoyan G. Chronic kidney disease-mineral-bone disorder: a new paradigm. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007;14:3–12. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Bone and mineral disorders in pre-dialysis CKD. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008;40:427–440. doi: 10.1007/s11255-008-9346-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regidor D, Kovesdy C, Mehrotra R, Rambod M, Jing J, McAllister C, Van Wyck D, Kopple J, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Mortality Predictability of Serum Alkaline Phosphatase in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008010014. [in press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blayney MJ, Pisoni RL, Bragg-Gresham JL, Bommer J, Piera L, Saito A, Akiba T, Keen ML, Young EW, Port FK. High alkaline phosphatase levels in hemodialysis patients are associated with higher risk of hospitalization and death. Kidney Int. 2008;74:655–663. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeziorska M, McCollum C, Woolley DE. Calcification in atherosclerotic plaque of human carotid arteries: associations with mast cells and macrophages. J Pathol. 1998;185:10–17. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199805)185:1<10::AID-PATH71>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lomashvili K, Garg P, O'Neill WC. Chemical and hormonal determinants of vascular calcification in vitro. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1464–1470. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lomashvili KA, Cobbs S, Hennigar RA, Hardcastle KI, O'Neill WC. Phosphate-induced vascular calcification: role of pyrophosphate and osteopontin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1392–1401. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000128955.83129.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lomashvili KA, Garg P, Narisawa S, Millan JL, O'Neill WC. Upregulation of alkaline phosphatase and pyrophosphate hydrolysis: potential mechanism for uremic vascular calcification. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1024–1030. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reust CE, Hall L. Clinical inquiries. What is the differential diagnosis of an elevated alkaline phosphatase (AP) level in an otherwise asymptomatic patient? J Fam Pract. 2001;50:496–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jorge C, Gil C, Possante M, Silva E, Andrade R, Santos N, Cruz A, Teixeira R, Ferreira A. Bone alkaline phosphatase besides intact parathyroid hormone in hemodialysis patients--any advantage? Nephron Clin Pract. 2005;101:c122–127. doi: 10.1159/000086682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torres PU. Bone alkaline phosphatase isoforms in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 2002;61:1178–1179. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00241-1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sit D, Kadiroglu AK, Kayabasi H, Atay AE, Yilmaz Z, Yilmaz ME. Relationship between bone mineral density and biochemical markers of bone turnover in hemodialysis patients. Adv Ther. 2007;24:987–995. doi: 10.1007/BF02877703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taal MW, Masud T, Green D, Cassidy MJ. Risk factors for reduced bone density in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:1922–1928. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.8.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutierrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, Rauh-Hain JA, Tamez H, Shah A, Smith K, Lee H, Thadhani R, Juppner H, Wolf M. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:584–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toussaint ND, Lau KK, Strauss BJ, Polkinghorne KR, Kerr PG. Associations between vascular calcification, arterial stiffness and bone mineral density in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:586–593. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raggi P, Bellasi A, Ferramosca E, Block GA, Muntner P. Pulse wave velocity is inversely related to vertebral bone density in hemodialysis patients. Hypertension. 2007;49:1278–1284. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.086942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathew S, Lund RJ, Strebeck F, Tustison KS, Geurs T, Hruska KA. Reversal of the adynamic bone disorder and decreased vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease by sevelamer carbonate therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:122–130. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Eps CL, Jeffries JK, Anderson JA, Bergin PT, Johnson DW, Campbell SB, Carpenter SM, Isbel NM, Mudge DW, Hawley CM. Mineral metabolism, bone histomorphometry and vascular calcification in alternate night nocturnal haemodialysis. Nephrology (Carlton) 2007;12:224–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2006.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoppet M, Shanahan CM. Role for alkaline phosphatase as an inducer of vascular calcification in renal failure? Kidney Int. 2008;73:989–991. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Neill WC. Pyrophosphate, alkaline phosphatase, and vascular calcification. Circ Res. 2006;99:e2. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000234909.24367.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shanahan CM. Vascular calcification. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2005;14:361–367. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000172723.52499.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drueke TB. Is parathyroid hormone measurement useful for the diagnosis of renal bone disease? Kidney Int. 2008;73:674–676. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stavroulopoulos A, Porter CJ, Roe SD, Hosking DJ, Cassidy MJ. Relationship between vitamin D status, parathyroid hormone levels and bone mineral density in patients with chronic kidney disease stages 3 and 4. Nephrology (Carlton) 2008;13:63–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodman WG. Comments on plasma parathyroid hormone levels and their relationship to bone histopathology among patients undergoing dialysis. Semin Dial. 2007;20:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutchison AJ, Whitehouse RW, Boulton HF, Adams JE, Mawer EB, Freemont TJ, Gokal R. Correlation of bone histology with parathyroid hormone, vitamin D3, and radiology in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 1993;44:1071–1077. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mussolino ME, Armenian HK. Low bone mineral density, coronary heart disease, and stroke mortality in men and women: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:841–846. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher AA, Southcott EK, Srikusalanukul W, Davis MW, Hickman PE, Potter JM, Smith PN. Relationships between myocardial injury, all-cause mortality, vitamin D, PTH, and biochemical bone turnover markers in older patients with hip fractures. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2007;37:222–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen ND, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV. Bone loss, weight loss, and weight fluctuation predict mortality risk in elderly men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1147–1154. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raggi P, Kleerekoper M. Contribution of bone and mineral abnormalities to cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:836–843. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02910707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsubara K, Suliman ME, Qureshi AR, Axelsson J, Martola L, Heimburger O, Barany P, Stenvinkel P, Lindholm B. Bone mineral density in end-stage renal disease patients: association with wasting, cardiovascular disease and mortality. Blood Purif. 2008;26:284–290. doi: 10.1159/000126925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kuwae N, Regidor DL, Kovesdy CP, Kilpatrick RD, Shinaberger CS, McAllister CJ, Budoff MJ, Salusky IB, Kopple JD. Survival predictability of time-varying indicators of bone disease in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;70:771–780. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cunningham J, Sprague SM, Cannata-Andia J, Coco M, Cohen-Solal M, Fitzpatrick L, Goltzmann D, Lafage-Proust MH, Leonard M, Ott S, Rodriguez M, Stehman-Breen C, Stern P, Weisinger J. Osteoporosis in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:566–571. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jamal SA, Hayden JA, Beyene J. Low bone mineral density and fractures in long-term hemodialysis patients: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:674–681. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.02.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piraino B, Chen T, Cooperstein L, Segre G, Puschett J. Fractures and vertebral bone mineral density in patients with renal osteodystrophy. Clin Nephrol. 1988;30:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jassal SK, von Muhlen D, Barrett-Connor E. Measures of renal function, BMD, bone loss, and osteoporotic fracture in older adults: the Rancho Bernardo study. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:203–210. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klawansky S, Komaroff E, Cavanaugh PF, Jr, Mitchell DY, Gordon MJ, Connelly JE, Ross SD. Relationship between age, renal function and bone mineral density in the US population. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:570–576. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1435-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindergard B, Johnell O, Nilsson BE, Wiklund PE. Studies of bone morphology, bone densitometry and laboratory data in patients on maintenance hemodialysis treatment. Nephron. 1985;39:122–129. doi: 10.1159/000183355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taal MW, Roe S, Masud T, Green D, Porter C, Cassidy MJ. Total hip bone mass predicts survival in chronic hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1116–1120. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD, Kamranpour N, Fogelman AM, Navab M. HDL-inflammatory index correlates with poor outcome in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2007;72:1149–1156. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colman S, Bross R, Benner D, Chow J, Braglia A, Arzaghi J, Dennis J, Martinez L, Baldo DB, Agarwal V, Trundnowski T, Zitterkoph J, Martinez B, Khawar OS, Kalantar-Zadeh K. The Nutritional and Inflammatory Evaluation in Dialysis patients (NIED) study: overview of the NIED study and the role of dietitians. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15:231–243. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shantouf R, Budoff MJ, Ahmadi N, Tiano J, Flores F, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Effects of sevelamer and calcium-based phosphate binders on lipid and inflammatory markers in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28:275–279. doi: 10.1159/000111061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Brennan ML, Hazen SL. Serum myeloperoxidase and mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:59–68. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.WHO. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep. 1994:1–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mehrotra R, Kermah D, Fried L, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Khawar O, Norris K, Nissenson A. Chronic peritoneal dialysis in the United States: declining utilization despite improving outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2781–2788. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006101130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beddhu S, Bruns FJ, Saul M, Seddon P, Zeidel ML. A simple comorbidity scale predicts clinical outcomes and costs in dialysis patients. Am J Med. 2000;108:609–613. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00371-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, Liu ST, Weinstein SR, Mosler TP, Tseng PH, Flores FR, Callister TQ, Raggi P, Berman DS. Long-term prognosis associated with coronary calcification: observations from a registry of 25,253 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1860–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson EE, Hong CD, Pesce AL, Peterson DW, Singh S, Pollak VE. Anthropometric norms for the dialysis population. Am J Kidney Dis. 1990;16:32–37. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80782-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levin A, Bakris GL, Molitch M, Smulders M, Tian J, Williams LA, Andress DL. Prevalence of abnormal serum vitamin D, PTH, calcium, and phosphorus in patients with chronic kidney disease: results of the study to evaluate early kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2007;71:31–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basiotis PP, Welsh SO, Cronin FJ, Kelsay JL, Mertz W. Number of days of food intake records required to estimate individual and group nutrient intakes with defined confidence. J Nutr. 1987;117:1638–1641. doi: 10.1093/jn/117.9.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Block G, Kelly MP, Schroepfer C, Rodriguez RA, Humphreys MH. Near infra-red interactance for longitudinal assessment of nutrition in dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2001;11:23–31. doi: 10.1016/s1051-2276(01)91938-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kuwae N, Wu DY, Shantouf RS, Fouque D, Anker SD, Block G, Kopple JD. Associations of body fat and its changes over time with quality of life and prospective mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:202–210. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tornel PL, Ayuso E, Martinez P. Evaluation of the turnaround time of an integrated preanalytical and analytical automated modular system in a medium-sized laboratory. Clin Biochem. 2005;38:548–551. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Rose L, Buring JE, Cook NR. Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1557–1565. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Erbagci AB, Tarakcioglu M, Aksoy M, Kocabas R, Nacak M, Aynacioglu AS, Sivrikoz C. Diagnostic value of CRP and Lp(a) in coronary heart disease. Acta Cardiol. 2002;57:197–204. doi: 10.2143/AC.57.3.2005389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pecoits-Filho R, Barany P, Lindholm B, Heimburger O, Stenvinkel P. Interleukin-6 is an independent predictor of mortality in patients starting dialysis treatment. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1684–1688. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.9.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beutler B, Cerami A. The biology of cachectin/TNF--a primary mediator of the host response. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:625–655. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.003205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med. 1989;8:551–561. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]