Abstract

Objective

Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 (APS1) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by progressive organ-specific autoimmunity. There is scant information on APS1 in ethnic groups other than European Caucasians. We studied clinical aspects and autoimmune regulator (AIRE) gene mutations in a cohort of Indian APS1 patients.

Design

Twenty-three patients (19 families) from six referral centres in India, diagnosed between 1996 and 2016, were followed for [median (range)] 4 (0.2–19) years.

Methods

Clinical features, mortality, organ-specific autoantibodies and AIRE gene mutations were studied.

Results

Patients varied widely in their age of presentation [3.5 (0.1–17) years] and number of clinical manifestations [5 (2–11)]. Despite genetic heterogeneity, the frequencies of the major APS1 components (mucocutaneous candidiasis: 96%; hypoparathyroidism: 91%; primary adrenal insufficiency: 55%) were similar to reports in European series. In contrast, primary hypothyroidism (23%) occurred more frequently and at an early age, while kerato-conjunctivitis, urticarial rash and autoimmune hepatitis were uncommon (9% each). Six (26%) patients died at a young age [5.8 (3–23) years] due to septicaemia, hepatic failure and adrenal/hypocalcaemic crisis from non-compliance/unexplained cause. Interferon-α and/or interleukin-22 antibodies were elevated in all 19 patients tested, including an asymptomatic infant. Eleven AIRE mutations were detected, the most common being p.C322fsX372 (haplotype frequency 37%). Four mutations were novel, while six others were previously described in European Caucasians.

Conclusions

Indian APS1 patients exhibited considerable genetic heterogeneity and had highly variable clinical features. While the frequency of major manifestations was similar to that of European Caucasians, other features showed significant differences. A high mortality at a young age was observed.

Keywords: autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome 1, APECED syndrome, autoimmune regulator gene, India

Introduction

Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 (APS1) is a rare and potentially life-threatening genetic disorder resulting from homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the autoimmune regulator (AIRE) gene (OMIM phenotype #240300) (1, 2). It is diagnosed by the presence of at least two of three major components: chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (MCC), hypoparathyroidism (HP) and primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) (3, 4, 5, 6, 7). In addition, it is characterized by progressive autoimmune involvement of multiple other tissues and ectodermal dystrophies (3, 4, 5, 6, 7) and autoantibodies against a broad range of antigens in affected tissues (5, 6, 7, 8, 9). The clinical features and severity of APS1 vary widely among individual patients and even among siblings (3, 4, 5, 6, 7).

AIRE is expressed primarily in thymic medullary epithelial cells, where it regulates expression of tissue-restricted peripheral antigens and subsequent negative selection of self-reactive T-cells (10). The AIRE gene consists of 14 exons, with 122 different pathogenic mutations being described in patients with APS1 (Human Gene Mutation Database; http://www.hgmd.cf.uk/, accessed December 2, 2016). The frequency of APS1 is highest among communities with genetic homogeneity, such as Finns (3), Sardinians (11) and Iranian Jews (12), where specific founder mutations have been described. In contrast to Finn and Sardinian patients who have null mutations leading to a severe phenotype, Iranian Jews have a missense mutation (p.Y85C), which may explain their milder phenotype (infrequent MCC and PAI) (12).

The vast majority of studies on APS1 are in Caucasians of European origin, and data on other ethnic groups are scarce, consisting mainly of case reports (13, 14, 15). The Indian population is genetically complex, with ancestral gene pools, admixture due to migration and endogamy along lines of caste and sub-caste (16, 17). In addition, consanguinity is frequent in some communities (16). These features are likely to result in complex genetic associations, including the possibility of founder mutations within endogamous communities (16). In addition to AIRE mutations, socio-economic and environmental factors may affect the clinical spectrum and prognosis of the disorder. There is currently little information on APS1 in Indian patients (18, 19, 20, 21). In an earlier study of nine Indian patients, we described five different AIRE mutations, of which two were novel (20).

In the current study, we report on the spectrum of clinical features, mortality, organ-specific autoantibodies and AIRE mutations in a longitudinally followed cohort of 23 Indian patients with APS1.

Materials and methods

Patients and controls

We enrolled 23 patients (19 families) with APS1 [(median age 14 years; range 0.5–30 years); 12 males], diagnosed between 1996 and 2015. The study comprises 11 patients presenting to our referral hospital in the north Indian city of Lucknow, and 12 patients from five academic centres in different regions of the country (Supplementary Fig. 1, see section on supplementary data given at the end of this article). We included nine patients we reported in 2006 (20), whose additional data over the next 10 years are presented (patients 15–23, Supplementary Table 1). Nineteen patients were of Indo-European, and four were of Dravidian ethno-linguistic ancestry. A history of consanguinity was present in 10 (53%) families. The patients were followed prospectively for 4 (0.2–19) years. Informed written consent was obtained from patients or their parents, and the study was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

The diagnosis of APS1 was made if any two of three major manifestations viz. MCC, HP or autoimmune PAI were present. In family members, a single feature was sufficient for diagnosis. A 5-month-old asymptomatic infant, diagnosed by genetic screening, was included. All patients were initially evaluated by a consultant paediatrician/endocrinologist at each centre. A common protocol was used to record data at all sites. The diagnosis of components of APS1 was made by clinical evaluation and biochemical, endocrine, radiological and antibody testing, as previously described (3, 4; Supplementary Table 2). In addition, previous records were evaluated, and relevant consultations were obtained. PAI was managed with physiological replacement doses of oral prednisolone and fludrocortisone; oral MCC with local clotrimazole, and pharyngeal infection with oral/intravenous fluconazole; and HP with high-dose oral calcium and calcitriol. All patients and/or their care-givers were repeatedly advised about stress dosing. Patients were followed at intervals of 6–12 months in their respective hospitals. Adequate treatment of disease components was assessed at each visit, and testing for new manifestations was conducted annually. All patients were finally evaluated in the clinic or contacted telephonically between March and September 2016.

Detection of autoantibodies

Antibodies were measured in 19 patients. IFN-α2 antibody was tested by a competitive europium-based time-resolved fluorescence assay in 17 subjects (22) and by a radioligand binding assay in 2 patients (23). Antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), tyrosine phosphatase (IA2), 21-hydroxylase (21-OH), interleukin-22 (IL-22), side-chain cleavage (SSC), tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH), cytochrome P4501A2 (CYP1A2), potassium channel regulator (KCNRG), bacterial/permeability-increasing fold-containing B1 (BP1FB1) and transglutaminase 4 (TGM4) antigens were measured by radioligand binding assays (24). Gastric parietal cell and liver/ kidney/ microsomal type 1 antibodies were detected using indirect immunofluorescence (AESKU Diagnostics, Wendelsheim, Germany) and thyroid peroxidase antibodies by chemiluminescence (Immulite 1000, Siemens, Germany).

AIRE sequencing

In probands, all 14 exons of AIRE gene were amplified by PCR (20, 24). Bidirectional sequencing was conducted on an ABI3130XL analyser (Applied Biosystems), and sequences were compared with the AIRE mRNA reference sequence (NM_000383.3). In family members, the affected exon was sequenced.

The frequency of the novel AIRE mutation, c.1637G>T, was assessed in 50 healthy subjects by sequencing exon 14. The prevalence of another novel mutation, c.32T>C, was determined in 70 control subjects by PCR-RFLP. A 406-base pair (bp) region of exon 1 was amplified and cut with restriction endonuclease Dde1 (New England Biolabs, Hertfordshire, UK). The wild-type sequence gave bands of 226 and 180 bp, whereas the fragment containing the mutation remained uncut.

Statistical analysis

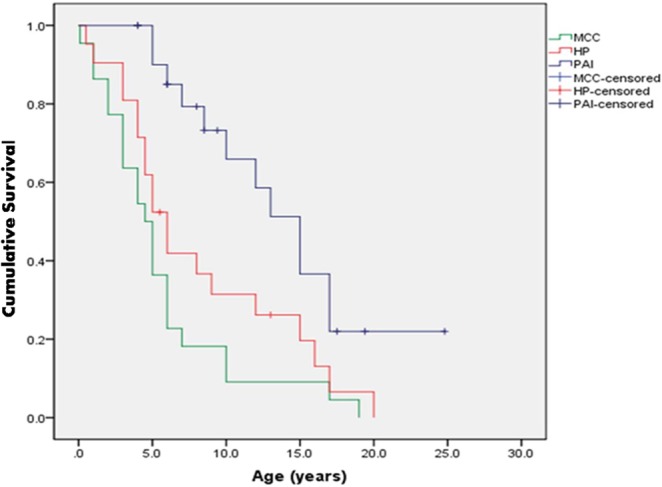

Continuous data were expressed as median (range). Groups were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test or chi-square test/Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Kaplan Meier survival analyses were used to depict onset of the three major manifestations of APS1. Analyses was performed with the statistical software package SPSS, version 21.0 (IBM).

Results

Clinical features

Clinical features were analysed in 22 symptomatic patients (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). There was wide variation in the frequency and severity of manifestations, even among subjects carrying the c.967_979del13bp mutation. The median age at diagnosis was 3.5 (0.1–17) years. While 11 (50%) patients were diagnosed <3 years, in two cases, the first manifestation was after 15 years. The initial clinical finding commonly included MCC (59%) or HP (27%), though presentation with PAI, AIH, type 1 diabetes (T1DM), hypothyroidism (HT) or diarrhoea was also noted (Table 1). Of the patients with MCC and HP, 65% and 55%, respectively, were diagnosed <5 years of age. Patients with PAI were older when diagnosed (67% between 5 and 15 years). The diagnostic dyad was present by median age of 8.5 (0.5–17) years. All three major manifestations were present in 9 (41%) patients; of these, 4 (44%) were <10 years of age (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Clinical findings in patients with APS1 (n = 22).

| Characteristic | Median (range) or n (%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 14 (0.5–30) | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 3.5 (0.1–17) | |

| Duration of illness (years) | 9.4 (0.5–29) | |

| Consanguinity | 10 (53%) | |

| Initial manifestationa: | ||

| Mucocutaneous candidiasis (MCC) | 13 (59) | Two patients had 3 manifestations each (HT, T1DM, diarrhoea; MCC, PAI, AIH) |

| Hypoparathyroidism (HP) | 6 (27) | |

| Primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) | 3 (14) | |

| Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) | 2 (9) | 3 patients had 2 manifestations each: MCC, HP (n = 2); HP, PAI (n = 1) |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Primary hypothyroidism (HT) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Diarrhoea | 1 (4.5) | |

| Age at diagnosis (years): | ||

| MCC | 5 (0.1–19) | |

| HP | 5 (0.5–20) | |

| PAI | 11 (5–17) | |

| Any 2 major manifestations | 8.5 (0.5–17) | |

| All 3 major manifestations | 13 (7–20) | |

| Overall frequency: | ||

| MCC | 21 (96) | |

| HP | 20 (91) | |

| PAI | 12 (55) | |

| All 3 major manifestations | 9 (41) | |

| No. of manifestations/patient | 5 (2––11) | |

| Associated disorders: | ||

| HP | 5 (23) | Unusual manifestations: facial dysmorphism (2 patients each); ptosis, sinusitis, nasal polyposis, buphthalmos, pigmented retinal dystrophy (one patient each) |

| Primary ovarian insufficiencyb | 3/5 (60) | |

| Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism | 1 (4.5) | |

| T1DM | 2 (9) | |

| AIH | 2 (9) | |

| Diarrhoea/obstipation | 6 (27) | |

| Anaemia | 7 (32) | 4/7 patients with anaemia were PCA positive |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency | 3/14 (21) | |

| Enamel hypoplasiac | 11 (61) | |

| Nail dystrophyc | 4 (22) | No patient had oral or oesophageal carcinoma, primary testicular failure or renal tubular disorder |

| Alopecia | 6 (27) | |

| Vitiligo | 6 (27) | |

| Urticarial rash | 2 (9) | |

| Keratoconjunctivitis | 2 (9) | |

| Sicca syndrome | 2 (9) | |

| Pigmented retinal dystrophy | 1 (4.5) | |

| Pneumonitis | 1 (4.5) | |

| Hyposplenia | 1 (4.5) | |

| IFN-α antibody | 19/20 (95) | Absent in 1 asymptomatic infant |

| IL-22 antibody | 17/19 (89) | Absent in 2 patients with MCC |

| Other antibodies: | ||

| TPO/TMA | 7/23 (30) | LKM and CYP1A2 antibody absent in all patients; |

| 21OH | 11 (58) | |

| SCC | 9 (47) | |

| Parietal cell | 7/21 (33) | TGM4 antibody present only in post-pubertal males; no patient with GAD antibody had T1DM |

| GAD | 6/17 (35) | |

| IA2 | 1 (5) | |

| TPH | 9 (47) | |

| TGM4 | 4 (21) | |

| BP1FB1 | 2 (10) | |

| KCNRG | 1 (5) | |

| Mortality: | ||

| Frequency | 6 (26%) | Septicaemia (n = 2), adrenal crisis (n = 2), hepatic failure (n = 1), unexplained (n = 1) |

| Age at death | 5 (3–23) |

Frequency of clinical manifestations calculated for 22 symptomatic patients; antibodies were measured in 19 subjects unless mentioned otherwise.

Three patients had two manifestations at initial presentation; bpost-pubertal females only; cenamel hypoplasia and nail pitting were accurately identified in 18 subjects.

TPO: thyroid peroxidase antibody; 21-OH: 21-hydroxylase antibody; SCC: side-chain cleavage antibody; PCA: parietal cell antibody; IFN-α: interferon alpha; IL-22: interleukin-22; TMA: thyroid microsomal antibody; GAD: glutamic acid decarboxylase; TPH: tryptophan hydroxylase; cytochrome P4501A2 (CYP1A2), potassium channel regulator (KCNRG); bacterial/permeability-increasing fold-containing B1 (BP1FB1); transglutaminase 4 (TGM4); LKM: liver/ kidney/ microsomal type 1.

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier analysis of cumulative survival frequency of three major manifestations. Cumulative frequency of mucocutaneous candidiasis, hypoparathyroidism and primary adrenal insufficiency at different ages in 22 patients with APS1. MCC: mucocutaneous candidiasis; HP: hypoparathyroidism; PAI: primary adrenal insufficiency.

The frequencies of other clinical manifestations are shown in Table 1. The median number of manifestations/patient were 5 (2–11) (Supplementary Table 1) and increased with duration. Among endocrine manifestations, HT was detected in 23% of subjects, at a relatively young age [16 (2–17) years]. Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) was present in 60% of post-pubertal females. No male had primary hypogonadism, though one patient had isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (IHH). T1DM was detected in 2 (9%) patients, though GADA frequency was considerably higher (35%). Enteropathy (diarrhoea 27%, obstipation 5%) and vitamin B12 deficiency (21%) were the most frequent gastrointestinal features. However, autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) was uncommon, being present in 2 (9%) children (onset at 2.5 and 5 years). Of these, patient #1 (Supplementary Table 1) was treated with high-dose oral prednisolone, followed by prednisolone and azathioprine, while patient #2 died prior to initiation of treatment. Enamel hypoplasia (EH) was present in 61% of patients. Frequent skin manifestations included vitiligo (27%) and alopecia (27%). However, urticarial skin eruptions (2 patients, 9%) were infrequent. Ocular findings were uncommon: keratoconjunctivitis (KC) and sicca syndrome in 2 patients, while one subject had pigmented retinal dystrophy (onset 21 years). One patient had suspected pneumonitis (chronic cough, reticular shadows on chest radiology and restrictive features on pulmonary testing) but was negative for KGNRG and BP1FB1 antibodies. No patient had renal tubulo-intestinal disease, early hypertension or oral/oesophageal cancer. Unusual features included facial dysmorphism (2 patients) and buphthalmos (1 patient).

Mortality

Six (27%) patients died during a short follow-up at the age of 5 (range 4–23) years (Supplementary Table 3). Four patients died at home, but an autopsy report was not available for any patient. Causes included septicaemia following pneumonia in 2 patients (one patient with hyposplenism), hepatic failure (1 patient) and likely adrenal or hypocalcaemic crisis in 2 siblings due to parental negligence. A 4-year-old patient with MCC and HP, who was well during clinic visit, died suddenly at home after 1 week. Her ACTH-stimulated cortisol response was normal, though 21OH antibody was positive at 3.5 years of age. Death from undiagnosed APS1, prior to identification of the probands, was suspected in 5 families.

Autoantibodies

IFN-α and IL-22 antibodies were elevated in 95% and 89% of patients, respectively (Table 1). Each patient was positive for at least one antibody. An asymptomatic 5-month-old infant (patient 12) with compound heterozygous AIRE mutations had elevated IL-22 antibody. Antibody against 21-OH was positive in 9/12 (75%) PAI patients and had positive predictive value (PPV) of 82%; SCC antibody was present in 8/12 (66%) patients (PPV 100%). SCC antibody identified all 3 post-pubertal females with POI. In contrast, all 3 post-pubertal males with this antibody had normal puberty. TGM4 antibody was present in 4 post-pubertal males, but was absent in pre-pubertal males and all females. Antibodies against pulmonary antigens KCNRG (n = 1) and BP1FB1 (n = 2) were infrequent.

AIRE mutations

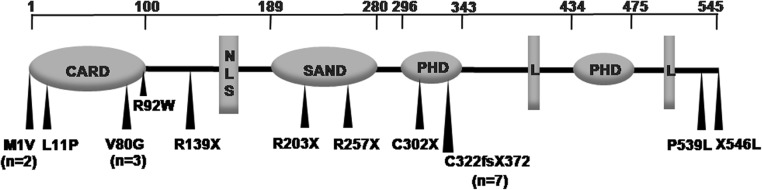

AIRE mutations were detected in 22 patients and deduced in sibling #5. All patients had homozygous mutations, except 3 affected members of one family with compound heterozygote mutations. Eleven different mutations were noted (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2), the most frequent being c.967_979del13bp (p.C322fsX372) in exon 8 [allele frequency 37%]. Patients with missense mutations (n = 9) and those with mutations resulting in premature termination (n = 13) had no differences in clinical features. Among patients from the state of Uttar Pradesh, p.C322fsX372 mutation was detected in 4 of 5 (80%) Muslim probands, but was absent in all 4 Hindu patients (exact P = 0.04). The mutation p.V80G was present in all 3 probands belonging to the small Vanika Vaisya community in Kerala. These patients had an early onset with MCC (<2 years) and multiple (5–7) clinical manifestations, including HT in 2 patients.

Figure 2.

Location of AIRE mutations detected in Indian APS1 probands. The location of mutations observed in 19 probands is shown in relation to the functional domains of the AIRE protein. All mutations were homozygous except for compound heterozygous mutation (p.M1V/p. R92W) in 3 members of one family. The mutation p.C322fs372X (7 probands) was the most frequent, followed by p.V80G (3 probands) and p.M1V (2 probands). All other mutations were identified in only a single proband. CARD: caspase activation and recruitment domain; NLS: nuclear localization signal; SAND: Sp100, AIRE, NucP41/75, DEAF-1 DNA-binding domain; PHD: plant homeodomain zinc finger; L: LXXLL nuclear receptor interaction motif.

Four mutations in this cohort have not been previously detected in other ethnic groups. Of these, p.V80G and p.C302X have been reported by us earlier (20). A novel mutation, p. L11P (patient #3), was located in the conserved hydrophobic region of the caspase recruitment (CARD) domain (25). This mutation was absent in all controls. The patient had severe features with MCC and HP in infancy and 21OH antibody by 3 years. Another unreported mutation, p.X546L+59aa (patient 8), affected the terminal codon (c.1637G>T), leading to possible addition of 60 amino acids to the C-terminal portion and consequent protein instability. Both parents were heterozygous for the mutation, which was absent in controls. The patient had MCC and PAI, severe vitamin B12 deficiency and possible autoimmune pneumonitis.

Discussion

This is among the largest detailed study of APS1 in an ethnic group other than that of European Caucasian background. We noted considerable variation in the onset and severity of clinical features in this genetically heterogeneous cohort. While the frequencies of the three major manifestations of APS1 were similar to those in patients of European origin, differences were noted in other clinical features and a high mortality at a young age was present.

Despite differences in their genetic and environmental background, MCC, HP and PAI followed a similar pattern to that reported in many previous series (3,4, 5, 6, 7, 24, 26, 27). MCC and HP appeared earliest and had a high prevalence (85% and 70%, respectively, by 10 years), while PAI was diagnosed later and was present in three-quarters of subjects by 20 years. In contrast, other clinical features were highly variable, showing both similarities and differences with European patients. The high frequency of EH, diarrhoea, vitiligo, alopecia and POI reported in most series was also present in our cohort. However, in contrast to the genetically homogeneous patients from Finland and Sardinia, who had a high frequency of AIH (18–27%) and KC (22–36%) (4, 6), a lower prevalence (9% each) was noted in our cohort. In addition, a high frequency of HT (23%) was present in our relatively young cohort, in contrast to its absence (6) or later occurrence (4) in these two series.

We compared our patients with genetically heterogeneous cohorts where p.C322fsX372 mutation was the most common mutation e.g. series from Norway and North America. Similar to our patients, a low frequency of AIH, KC, pneumonitis and rash, along with a high frequency of HT (though with later-onset) was noted in Norwegian subjects (5). In contrast, North American patients had a significantly higher prevalence of rash, enteropathy, gastropathy, sicca syndrome, pneumonitis and AIH (7). These differences in clinical manifestations may be due to the diversity of AIRE mutations, influence of other genetic or environmental factors or differences in screening strategies.

Despite a relatively short follow-up, nearly a quarter of the patients in this report died at a young age due to pneumonia, AIH and sudden death at home. In at least two siblings, death was preventable since parental negligence lead to possible adrenal or hypocalcaemic crises. In previous reports, mortality is reported to be 3–29% (4, 5, 6, 7, 27). In a study of 91 Finn patients, mortality was 29%. However, the follow-up was longer than the current report (4). While some causes of death, such as AIH, were similar to our series, others were noted only in Finn patients e.g. unexpected death in loners and oral/oesophageal cancer. In the series of Norwegian patients, 18% died during a long follow-up, mainly due to cancer or adrenal and hypocalcaemic crises (5). The high mortality in our study is likely to be multifactorial, including difficulties in educating caregivers, lack of local medical facilities, poor knowledge of the disorder among paediatricians and, possibly, a higher risk of infections.

IFN-α and IL-22 antibodies were present in 95% and 90% of patients, respectively, confirming their value as sensitive test for APS1 in this cohort (5, 6, 7, 9, 22, 23). IL-22 antibody was detected in a 5-month-old asymptomatic sibling, which is among the earliest diagnosis reported (28). The frequency and significance of antibodies against 21OH, SCC, GAD and TGM4 was similar to previous reports (5, 6, 7, 8, 29). However, in contrast to a previous report (7), antibodies against pulmonary antigens BP1FB1 (10%) and KCNRG (5%) were uncommon, and no patient with these had evidence of pulmonary disease.

As expected from the wide ethnic diversity in India, our cohort was genetically heterogeneous with 11 different AIRE mutations. Nine mutations were detected in probands of Indo-European ethnicity (from north and west India), 6 of which have been reported earlier in patients of European ancestry. Among these, p.R257X, p.R139X and p.R203X are founder mutations in Finland, Sardinia and Sicily, respectively (1, 11, 30), while p.C322fsX372 is frequent in many parts of Europe, United Kingdom and the USA (5, 7, 12, 27, 30, 31, 32). The other mutations have been reported as isolated cases (15, 31, 32). In contrast, both mutations (p.V80G and p.X546L+59aa) in patients from south India (of Dravidian ancestry) are not described in other ethnic groups. However, a different variation affecting the terminal codon (c.1638A>T; p.X546C+59aa) has been reported in two Finnish patients (Human Gene Mutation Database; http://www.hgmd.cf.uk/). Further studies in populations which are genetically divergent from Caucasians may reveal other novel mutations or clinical findings.

The most common mutation among our patients, present in 37% of probands, was p.C322fsX372. Interestingly, this mutation was present in 80% of unrelated Muslim probands from Uttar Pradesh, but was absent in all five Hindu patients from this state. The Muslim population in this state is highly endogamous with high consanguinity. Further study is required to confirm if this mutation arose from a single ancestral haplotype or originated through separate events. The finding of another patient with the p.V80G mutation from the small in-bred Vanika Vaisya community, in addition to the two we have reported earlier (20), reinforces the suggestion that it is a founder mutation.

Our study has certain limitations. While the study includes patients from different regions of India, it may not adequately reflect the complex overall clinical or genetic spectrum of the disorder in the country. In addition, despite using a common protocol for data collection and follow-up, some differences in data collection may have arisen in various centres. Lastly, sera or DNA samples were not available in all patients.

In summary, APS1 patients in this report were genetically heterogeneous, and while many AIRE mutations were similar to those in European Caucasian subjects, novel and founder mutations were detected. The clinical features varied widely, and there were both similarities and differences from patients of European origin. A high mortality at a young age was observed, underscoring the difficulties of management of this rare disorder in resource-limited circumstances.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest which could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

The study was supported by an intramural research grant from the Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow (EB), and the Swedish Research Council, The Torsten and Ragnar S€oderberg Foundations and Novonordik Foundation (OK).

Author contribution statement

G Z, E B and V B designed, acquired and analysed data; and drafted, revised and approved the manuscript. A N S and R A acquired and analysed data; and revised and approved the manuscript. N B, S K S, L Z, L Y, D E, S B, O K, N B, S K Y, A B, A S, V J, N S, A A, M S and S A acquired data, and revised and approved the manuscript.

References

- 1.The Finnish-German. APECED Consortium. An autoimmune disease, APECED, caused by mutations in a novel gene featuring two PHD-type zinc-finger domains. Autoimmune-Polyendocrinopathy-Candidiasis-Ectodermal Dystrophy. Nature Genetics 1997. 17 399–403. ( 10.1038/ng1297-399) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagamine K, Peterson P, Scott HS, Kudoh J, Minoshima S, Heino M, Krohn KJ, Lalioti MD, Mullis PE, Antonarakis SE, et al. Positional cloning of the APECED gene. Nature Genetics 1997. 17 393–398. ( 10.1038/ng1297-393) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahonen P, Myllarniemi S, Sipila I, Perheentupa J. Clinical variation of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) in a series of 68 patients. New England Journal of Medicine 1990. 322 1829–1836. ( 10.1056/nejm199006283222601) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perheentupa J. Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2006. 91 2843–2850. ( 10.1210/jc.2005-2611) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruserud Ø, Oftedal BE, Landegren N, Erichsen M, Bratland E, Lima K, Jørgensen AP, Myhre AG, Svartberg J, Fougner KJ, et al. A longitudinal follow-up of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2016. 101 2975–2983. ( 10.1210/jc.2016-1821) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melonie A, Willcox N, Meager A, Atzeni M, Wolff AS, Husebye ES, Furcas M, Rosatelli MC, Cao A, Congia M. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1: an extensive longitudinal study in Sardinian patients. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2012. 97 1114–1124. ( 10.1210/jc.2011-2461) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferre EMN, Rose SR, Rosenzweig SD, Burbelo PD, Romito KR, Niemela JE, Rosen LB, Break TJ, Gu W, Hunsberger S, et al. Redefined clinical features and diagnostic criteria in autoimmune polyendocrinopathycandidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy. Journal of Clinical Investigation Insight 2016. 1 e88782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soderbergh A, Myhre AG, Ekwall O, Gebre-Medhin G, Hedstrand H, Landgren E, Miettinen A, Eskelin P, Halonen M, Tuomi T, et al. Prevalence and clinical associations of 10 defined autoantibodies in autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2004. 89 557–562. ( 10.1210/jc.2003-030279) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meager A, Visvalingam K, Peterson P, Möll K, Murumägi A, Krohn K, Eskelin P, Perheentupa J, Husebye E, Kadota Y, et al. Anti-interferon autoantibodies in autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome type 1. PLoS Medicine 2006. 3 e289 ( 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030289) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abramson J, Husebye ES. Autoimmune regulator and self-tolerance-molecular and clinical aspects. Immunology Reviews 2016. 271 127–140. ( 10.1111/imr.12419) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosatelli MC, Meloni A, Meloni A, Devoto M, Cao A, Scott HS, Peterson P, Heino M, Krohn KJ, Nagamine K, et al. A common mutation in Sardinian autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal-dystrophy patients. Human Genetics 1998. 103 428–434. ( 10.1007/s004390050846) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Björses P, Halonen M, Palvimo JJ, Kolmer M, Aaltonen J, Ellonen P, Perheentupa J, Ulmanen I, Peltonen L. Mutations in the AIRE gene: effects on subcellular location and transactivation function of the autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy protein. American Journal of Human Genetics 2000. 66 378–392. ( 10.1086/302765) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seifi-Alan M, Shamsi R, Setoodeh A, Sayarifard F, Aghasi P, Kompani F, Ghafouri-Fard S, Abbasi F. Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy: report of three cases from Iran. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology Metabolism 2016. ( 10.1515/jpem-2016-0017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kogawa K, Kudoh J, Nagafuchi S, Ohga S, Katsuta H, Ishibashi H, Harada M, Hara T, Shimizu N. Distinct clinical phenotype and immunoreactivity in Japanese siblings with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1 (APS-1) associated with compound heterozygous novel AIRE gene mutations. Clinical Immunology 2002. 103 277–283. ( 10.1515/jpem-2016-0017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faiyaz-Ul-Haque M, Bin-Abbas B, Al-Abdullatif A, Abdullah AH, Toulimat M, Al-Gazlan S, Almutawa AM, Al-Sagheir A, Peltekova I, Al-Dayel F, et al. Novel and recurrent mutations in the AIRE gene of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome type 1 (APS1) patients. Clinical Genetics 2009. 76 431–440. ( 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01278.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reich D, Thangaraj K, Patterson N, Price AL, Singh L. Reconstructing Indian population history. Nature 2009. 461 489–494. ( 10.1038/nature08365) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moorjani P, Thangaraj K, Patterson N, Lipson M, Loh PR, Govindaraj P, Berger B, Reich D, Singh L. Genetic evidence for recent population mixture in India. American Journal of Human Genetics 2013. 93 422–438. ( 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.07.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laway BA, Ganie MA, War FA, Mir SA, Roshan R, Zargar AH. Varying presentation of type 1 polyglandular failure in India. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism 2010. 23 271–276. ( 10.1515/JPEM.2010.23.3.271) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhansali A, Kotwal N, Suresh V, Murlidharan R, Chattopadhyay A, Mathur K. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 1 without chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in a 16 year old male. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism 2003. 16 103–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaidi G, Sahu RP, Zhang L, George G, Bhavani N, Shah N, Bhatia V, Bhansali A, Jevalikar G, Jayakumar RV, et al. Two novel AIRE mutations in autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis- ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) among Indians. Clinical Genetics 2009. 76 441–448. ( 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01280.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahoo SK, Zaidi G, Srivastava R, Sarangi AN, Bharti N, Eriksson D, Bensing S, Kämpe O, Aggarwal A, Aggarwal R, et al. Identification of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 in patients with isolated hypoparathyroidism. Clinical Endocrinology 2016. 85 544–550. ( 10.1111/cen.13111) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oftedal BE, Kämpe O, Meager A, Ahlgren KM, Lobell A, Husebye ES, Wolff AS. Measuring autoantibodies against IL-17F and IL-22 in autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I by radioligand binding assay using fusion proteins. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology 2011. 74 327–333. ( 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2011.02573.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pearce SH, Cheetham T, Imrie H, Vaidya B, Barnes ND, Bilous RW, Carr D, Meeran K, Shaw NJ, Smith CS, et al. A common and recurrent 13-bp deletion in the autoimmune regulator gene in British kindreds with autoimmune polyendocrinopathy type 1. American Journal of Human Genetics 1998. 63 1675–1684. ( 10.1086/302145) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Barker JM, Babu S, Su M, Stenerson M, Cheng M, Shum A, Zamir E, Badolato R, Law A, et al. Immunoassay for anti-interferon autoantibodies that is highly specific for patients with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1. Clinical Immunology 2007. 125 131–137. ( 10.1016/j.clim.2007.07.015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferguson BJ, Alexander C, Rossi SW, Liiv I, Rebane A, Worth CL, Wong J, Laan M, Peterson P, Jenkinson EJ, et al. AIRE’s CARD revealed a new structure for central tolerance provokes transcriptional plasticity. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008. 283 1723–1731. ( 10.1074/jbc.m707211200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Betterle C, Greggio NA, Volpato M. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 1998. 83 1049–1055. ( 10.1210/jcem.83.4.4682) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dominguez M, Crushell E, Ilmarinen T, McGovern E, Collins S, Chang B, Fleming P, Irvine AD, Brosnahan D, Ulmanen I, et al. Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) in the Irish population. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism 2006. 19 1343–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolff AS, Sarkadi AK, Marodi L, Karner J, Orlova E, Oftedal BE, Kisand K, Olah E, Meloni A, Myhre AG, et al. Anti-cytokine autoantibodies preceding onset of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I features in early childhood. Journal of Clinical Immunology 2013. 33 1341–1348. ( 10.1007/s10875-013-9938-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landegren N, Sharon D, Shum AK, Khan IS, Fasano KJ, Hallgren Å, Kampf C, Freyhult E, Ardesjö-Lundgren B, Alimohammadi M, et al. Transglutaminase 4 as a prostate autoantigen in male subfertility. Science Translational Medicine 2015. 7 292ra101 ( 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa9186) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meloni A, Perniola R, Faà V, Corvaglia E, Cao A, Rosatelli MC. Delineation of the molecular defects in the AIRE gene in autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy patients from Southern Italy. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2002. 87 841–846. ( 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8209) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magitta FN, Pura M, Wolff ASB, Vanuga P, Meager A, Knappskog PM, Husebye ES. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I in Slovakia: relevance of screening patients with autoimmune Addison’s disease. European Journal of Endocrinology 2008. 158 705–709. ( 10.1530/EJE-07-0843) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heino M, Scott HS, Chen Q, Peterson P, Maenpaa U, Papasavvas MP, Mittaz L, Barras C, Rossier C, Chrousos GP, et al. Mutation analyses of North American APS-1 patients. Human Mutation 1999. 13 69–74. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a