Abstract

Background

An elevated white blood cell (WBC) count is a characteristic finding in pneumococcal pneumonia. Very low WBC counts, occurring in some cases, are often associated with overwhelming pneumonia and have been attributed to alcohol-induced suppression of bone marrow. However, a systematic study of neutropenia, leukocytosis, alcohol ingestion, and cirrhosis in pneumococcal pneumonia has not been previously reported.

Methods

Using a database of patients with pneumococcal pneumonia at our medical center, we extracted data on WBC counts at admission, differential counts, alcohol ingestion, and cirrhosis, and we related these to 7-day and 30-day mortality.

Results

White blood cell counts were <6000/mm3 in 49 of 481 patients (10.2%) with pneumococcal pneumonia and >25000/mm3 in 40 (8.3%). Mortality at 7 days was 18.4% and 12.5%, respectively, 5-fold and 3-fold greater in patients with WBC <6000 or >25000 than in those with WBC counts between 6000 and 25000 (P < .001). Increased band forms were not associated with a worse outcome (P = .12). Alcohol use and cirrhosis were not associated with WBC counts <6000 (P = .63 and P = .41, respectively).

Conclusions

In a large series of cases of pneumococcal pneumonia, WBC counts <6000 or >25000 correlated significantly with increased 7-day mortality. More than 10% band forms was not associated with a poor outcome. Alcohol abuse was not associated with low WBC or increased mortality. Our findings suggest that greater consideration be given to more intense care for patients with bacterial pneumonia who have very high or very low WBC counts at the time of hospital admission.

Keywords: alcoholism, leukocytosis, neutropenia, pneumonia, white blood cell count

The white blood cell (WBC) count is generally expected to rise in response to infection and has long been used by clinicians to help diagnose pneumonia, determine its etiology, and predict patient outcomes [1, 2]. However, up to 25% of patients hospitalized for pneumococcal pneumonia [3] and up to 38% hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) [4] have a normal WBC count at the time of admission. Relatively few studies have examined in depth the relationship between WBC counts and prognosis. A low WBC count has often been said to be associated with poor outcomes both in bacteremic and nonbacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia, but not all studies have come to the same conclusion (Table 1). There is even less consensus about the prognostic value of very high WBC counts in pneumococcal pneumonia. Alcoholism has always been common among patients with pneumococcal pneumonia [2], and some investigators say that it increases mortality in pneumococcal [5, 6] or CAP [7, 8], but others have said that it has no effect on disease outcome [9, 10] (Table 1). Neutropenia in pneumonia is often attributed to the effect of alcohol ingestion [5, 11, 12].

Table 1.

Previous Reports of Prognostic Value of WBC Counts in Patients With Pneumococcal or Community-Acquired Pneumonia

| Author | Only Streptococcus pneumoniae | ↓ WBC as Riska | Definition (WBC/mm3) | Statistical Analysis | Odds Ratio or P Value | ↑ WBC as Risk |

Definition | Statistical Analysis | Alcohol Use as Risk | Statistical Analysis | Odds Ratio or P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heffron [2] | Yes | Yes | <10000 | No | ND | Yes | >40000 | No | NR | — | — |

| Austrian and Gold [9] | Yes | Yes Yes |

<5000 5–9000 |

No No |

ND ND |

Yes | >25000 | No | No | No | ND |

| Chomet and Gach [5] | No | Yes | <6000 | No | ND | No | — | — | Yes | No | ND |

| Hook et al [10] | Yes | Yes | <5000 | Yes | P < .001 | NR | — | — | NR | — | — |

| Perlino and Rimland [12] | Yes | Yes | ≤4000 | Yes | P < .001 | NR | — | — | No | Yes | P > .05 |

| Chang and Mylotte [23] | Yes | No | <5000 | Yes | P > .05 | No | >25000 | Yes | NR | — | — |

| Ortqvist [6] | Yes | Yes | <9000 | Yes | P < .05 | NR | — | — | Yes | Yes | P < .01 |

| Leroy et al [24] | No | Yes | <3500 | Yes | OR 5.0 | NR | — | — | NR | — | — |

| Watanakunakorn and Bailey [25] | Yes | Yes | <3000 3–11000 |

Yes Yes |

P < .001 P < .001 |

NR | — | — | NR | — | — |

| Mortensen et al [7] | Yes | Yes | <4000 | Yes | OR 2.99 | NR | — | — | Yes | Yes | P < .01 |

| Martens et al [26] | Yes | Yes | <9000 | Yes | OR 2.76 | NR | — | — | No | Yes | P > .05 |

| Menendez et al [27] | No | Yes | <4000 | Yes | OR 3.7 | NR | — | — | NR | — | — |

| Paganin et al [8] | No | Yes | <1000 | Yes | OR 2.48 | NR | — | — | Yes | Yes | RR 3.11 |

| Marrie and Wu [28] | No | Yes | <1000b | Yes | OR 2.05 | NR | — | — | NR | — | — |

| Furer et al [3] | Yes | No | <10000 | Yes | P = .69 | No | >25000 | No | NR | — | — |

| Blot et al [16] | Yes | Yes | <4000 | Yes | OR 13.7c | NR | — | — | No | Yes | P > .05 |

Abbreviations: ND, not done; NR, not reported; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; WBC, white blood cells.

aRisk in every study referred to death, except Menendez et al [27], which referred to treatment failure.

b Table 4 in this reference lists lymphocytes, which we believe is in error.

cStatistical analysis of a leukocyte score (neutropenia, lymphopenia, and monocytopenia).

To our knowledge, no previous study has systematically evaluated the prognostic significance of neutropenia, leukocytosis, and increased early forms (bandemia) in a single cohort of patients with pneumococcal pneumonia or has reported on the association of these factors with alcohol ingestion. We now present the results of such a study.

METHODS

Study Design

Using a database of all patients with pneumococcal infection seen at the Michael E. DeBakey Houston VA Medical Center since 2000, we selected those who were hospitalized from 2000 to 2013 with a final diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia. In accordance with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definitions, cases were stratified into the following: (1) proven pneumococcal pneumonia, a clinical syndrome of pneumonia with isolation of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the blood or another normally sterile body site; and (2) presumptive pneumococcal pneumonia, a clinical syndrome of pneumonia with a consistent sputum Gram stain and a sputum culture yielding S pneumoniae as the predominant isolate, but without blood culture confirmation.

Electronic medical records were reviewed, and the initial WBC count and differential at the time of presentation were extracted. We determined mortality 7 and 30 days after admission. Patients with leukemia or medication-induced neutropenia were excluded, but we did not exclude patients with cirrhosis, human immunodeficiency virus infection, or other immunocompromising conditions. Alcohol abuse was defined as either a diagnosis of alcoholism or alcohol abuse or the documentation in the medical record of regular consumption of >6 drinks per day at any time during the preceding 2 years. We also included in this category patients who had previously been diagnosed alcohol abusers if the medical record stated more vaguely that, for example, they were now “drinking again.” Cirrhosis was diagnosed based on review of all discharge summaries.

Statistics

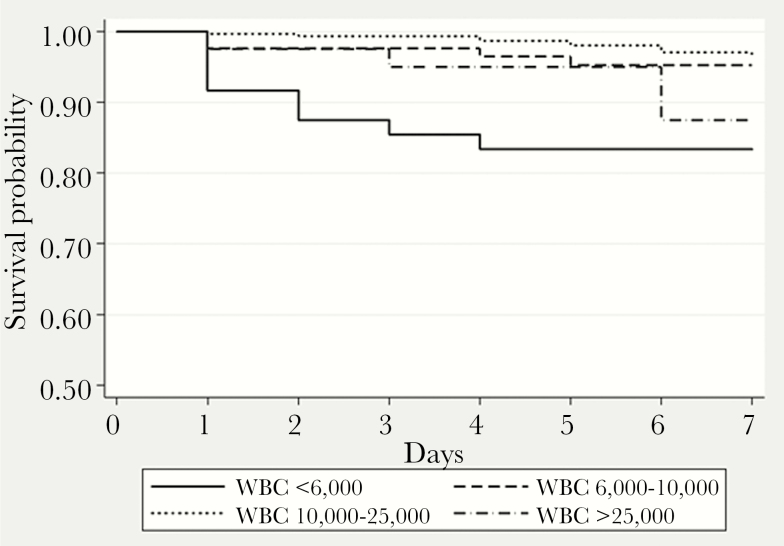

Descriptive data were reported as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. Differences across groups were compared using the χ2 test for categorical variables and the unpaired t tests or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables as appropriate. Survival at 7 days and 30 days of different groups of WBC were depicted using Kaplan-Meier methodology. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional-hazards models were used to determine the contribution of potential risk factors to risk of death. Results were reported as hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were performed on Stata, version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Our database listed 481 patients with pneumococcal pneumonia. Of these, 49 (10.2%) had WBC counts <6000, 85 (17.7%) had 6000–9999 WBC, 307 (63.8%) had WBC 10000–24999, and 40 (8.3%) had WBC >25000 (Table 2). Overall mortality at 7 days was 6.0%: 18.4% in patients with WBC <6000, and 12.5% in those with WBC >25000, significantly greater than the mortality of 3.8% in those with WBC counts of 6000 to 25000 (P < .001) (Table 2, Figure 1). At 30 days, mortality remained higher in patients who had been leukopenic at admission, but the difference was no longer significant for those who had had leukocytosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors Associated With Increased 7- or 30-Day Mortality in Patients With Pneumococcal Pneumonia

| Variable | No. of Patients | Mortality | Hazard Ratio | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-Day | 30-Day | ||||

| WBC <6000 | 49 | 18.4% | 30.6% | 5.66 | <.001 |

| WBC 6000–10000 | 85 | 5.9% | 8.2% | 1.49 | .50 |

| WBC 10000–25000 | 307 | 3.3% | 11.1% | (Reference) | |

| WBC >25000 | 40 | 12.5% | 12.5% | 3.94 | .01 |

| Immature forms ≤10% | 412 | 5.3% | 12.4% | (Reference) | |

| Immature forms >10% | 69 | 10.1% | 14.5% | 3.59 | .23 |

| Bacteremia | 164 | 9.8% | 15.2% | 2.08 | .06 |

| Alcohol abuse | 105 | 8.6% | 13.3% | 1.80 | .22 |

| Cirrhosis | 27 | 14.8% | 18.5% | 3.11 | .048 |

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cells.

aCompared to patients with 10000–25000 WBC.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve for 7-day survival. WBC, white blood cells.

A high number of early WBC forms was not associated with mortality. Thirty-four patients (7.1%) had 5%–10% bands, and 69 (14.3%) had >10% bands. There was no association between elevated band counts and mortality (P = .12). In fact, patients with >30% band forms appeared to have a lower mortality than those with 10%–20%, although small numbers of subjects precluded statistical analysis (Table 3). Alcohol abuse was cited in the records of 12 of 49 (24.5%) patients with WBC counts <6000 vs 93 of 432 (21.5%) in all patients with WBC ≥6000 (P = .63). Of 49 patients with WBC counts <6000, 4 (8.2%) had documented cirrhosis, vs 23 of 432 (5.3%) with WBC ≥6000 (P = .41). We found a tendency toward increased mortality among alcohol abusers, but even in our large series of cases, this number did not reach statistical significance (odds ratio [OR] = 1.80, P = .22) (Table 2). The rate of death in patients with cirrhosis was significantly greater than in those without cirrhosis (14%; OR = 3.11, P < .05).

Table 3.

Mortality and Presence of Band Forms

| Band Forms (%) | Number of Patients | Mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7 Days | 30 Days | ||

| 0–10 | 412 | 5.3% | 12.4% |

| 11–20 | 41 | 17.1% | 19.5% |

| 21–30 | 14 | 0% | 7.1% |

| 31–40 | 7 | 0% | 0% |

| >40 | 7 | 0% | 14.3% |

To relate WBC counts to bacteremia, we excluded 35 patients whose blood was not cultured and 18 who had received antibiotics before blood cultures were obtained. In the remaining 428 cases, 23 of 41 with WBC <6000 (56.1%) were bacteremic, significantly higher than the 36.0% of patients with WBC 6000–25000 (P = .01) (Table 4). The incidence of bacteremia in patients with WBC >25000 (15 of 37; 40.5%) was not greater than in those with WBC between 6000 and 25000 (P = .59). At day 7 of hospitalization, mortality was greater among bacteremic than nonbacteremic patients (16 of 164 [9.8%] vs 12 of 264 [4.5%]; P = .03), but this difference was not significant at 30 days (mortality = 15.2% and 12.5%, respectively; P = .42). Mean WBC counts in bacteremic and nonbacteremic cases were similar (15100 per mm3 ± 790 vs 14500 ± 690, respectively; P = .45).

Table 4.

Bacteremia and WBC Counts

| WBC Count | Number (%, 481 Total) | Number With Culture (%, 428 Total) | Bacteremia (%, 164 Total) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6000 | 49 (10.2%) | 41 (9.6%) | 23 (56.1%) | .012 |

| 6000–10000 | 85 (17.7%) | 73 (17.1%) | 20 (27.4%) | — |

| 10000–25000 | 307 (63.8%) | 277 (64.7%) | 106 (38.3%) | — |

| >25000 | 40 (8.3%) | 37 (8.6%) | 15 (40.5%) | .585 |

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cells.

aCompared with patients with 10000–25000 WBC.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study show that patients with pneumococcal pneumonia who, at the time of presentation, have WBC counts <6000 per mm3 have a >5-fold increase in the risk of death at 7 days compared with patients whose WBC counts are between 10000 and 25000. In the same comparison, patients with WBC counts >25000 had a >3-fold increase in mortality at 7 days. Somewhat surprisingly, we found no association between elevated band forms and outcome, and, paradoxically, the 7-day mortality actually appeared to decrease with >20% bands, although the sample size was very small (see Table 3). The high mortality in the 10%–20% group could indicate inadequate production of immature forms in some patients with bandemia in response to severe infection. Bacteremia was associated with increased mortality at 7 days but not at 30 days, probably because acuity of the disease caused death initially, whereas complications of the pneumonia were responsible for death at 30 days; others who have reported a lack of association between bacteremia and outcome [13] have focused on 30-day mortality.

Most but not all previous studies have shown that low WBC counts are associated with a poor outcome in patients who have pneumococcal pneumonia (Table 1). An association between extremes of WBC counts and death from pneumococcal pneumonia was noted as long ago as 1917 [14]. However, only a very few studies have provided data together with statistical analysis, and, to our knowledge, no previous study has analyzed the associations among low or very elevated WBC counts and mortality in a single cohort of patients. Some earlier investigators stated that alcohol ingestion is associated with a worse outcome in pneumococcal pneumonia [5, 6, 15], whereas others [9, 10] did not agree. Multivariate statistical analysis was not done in these studies but, in our study, revealed no significant association between mortality and alcohol ingestion. Cirrhosis was associated with >3-fold risk for mortality.

Based on anecdotal reports, earlier investigators attributed low WBC counts in pneumococcal pneumonia to toxic suppression of the bone marrow by alcohol [5, 11]. Perlino and Rimland [12] reported a significant association between alcoholism and WBC ≤4000 per mm3 in pneumococcal pneumonia. However, the present study with a much larger group of patients failed to confirm this finding: neither alcohol use nor cirrhosis was associated with WBC counts <6000 (P = .63 and P = .41, respectively). Blot et al [16] developed a leukocyte score based on neutrophil, lymphocyte, and monocyte counts, and they found no association between alcoholism and this leukocyte score, consistent with our findings. In more recent years, suppression of hematopoiesis by cytokines and exhaustion of marrow reserves have been cited as the causes for low WBC counts in sepsis [17], but the presence of large numbers of early forms (bands and metamyelocytes) in the peripheral blood appears to oppose this hypothesis.

Instead, we propose the following hypothesis to explain neutropenia in serious bacterial infections: acute bacterial infection stimulates the release of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukins 6 and 8, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, and CXCL-12, that mobilize the release of mature PMNs and immature forms (bands and metamyelocytes) from bone marrow [18, 19]. Infection also stimulates release of soluble E-selectin [19], triggering the complement cascade and activating vascular endothelium, especially in the lungs, causing intravascular leukostasis and capillary plugging by mature polymorphonuclear leukocytes [20–22]. As a result of these factors, the number of immature forms increases, while the number of circulating mature neutrophils declines. The final outcome depends upon the balance among these factors and the host’s response to them. Some patients with pneumococcal pneumonia who go untreated may initially have elevated WBC counts that then fall as the infection progresses, presumably depending upon the balance among the cytokines that are produced (D. M. M., unpublished observations, 1973–2015 and reference [5]).

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, in this study of a large number of patients with pneumococcal pneumonia, WBC counts that were very low (<6000) or elevated (>25000) correlated significantly with bacteremia and increased mortality. Bandemia was not associated with death. Neither alcoholism nor cirrhosis appeared to be responsible for the neutropenia. These data suggest that more intense care be regularly given to patients with pneumococcal pneumonia, and perhaps any bacterial pneumonia, who have very high or very low WBC counts.

Acknowledgments

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Wintrobe MW. Clinical Hematology. 6th ed Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Feibiger; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heffron R. Pneumonia with Special Reference to Pneumococcus Lobar Pneumonia. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Furer V, Raveh D, Picard E, et al. Absence of leukocytosis in bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia. Prim Care Respir J 2011; 20:276–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Venkatesan P, Gladman J, Macfarlane JT, et al. A hospital study of community acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Thorax 1990; 45:254–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chomet B, Gach BM. Lobar pneumonia and alcoholism: an analysis of thirty-seven cases. Am J Med Sci 1967; 253:300–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ortqvist A . Prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia requiring treatment in hospital. Importance of predisposing and complicating factors, and of diagnostic procedures. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1990;65:1-62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mortensen EM, Coley CM, Singer DE, et al. Causes of death for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: results from the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162:1059–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paganin F, Lilienthal F, Bourdin A, et al. Severe community-acquired pneumonia: assessment of microbial aetiology as mortality factor. Eur Respir J 2004; 24:779–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Austrian R, Gold J. Pneumococcal bacteremia with especial reference to bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia. Ann Intern Med 1964; 60:759–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hook EW, 3rd, Horton CA, Schaberg DR. Failure of intensive care unit support to influence mortality from pneumococcal bacteremia. JAMA 1983; 249:1055–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mcfarland W, Libre EP. Abnormal leukocyte response in alcoholism. Ann Intern Med 1963; 59:865–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Perlino CA, Rimland D. Alcoholism, leukopenia, and pneumococcal sepsis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985; 132:757–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Amaro R, Liapikou A, Cilloniz C, et al. Predictive and prognostic factors in patients with blood-culture-positive community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2016; 48:797–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Avery OT, Chickering HT, Cole R, Dochez AR. Acute Lobar Pneumonia: Prevention and Serum Treatment. Monographs of the Rockefeller Institute; 1917, No. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Painton JF, Hicks AM, Hantman S. A clinical analysis of primary atypical pneumonia with a discussion of electrocardiographic findings. Ann Intern Med 1946; 24:775–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blot M, Croisier D, Pechinot A, et al. A leukocyte score to improve clinical outcome predictions in bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia in adults. Open Forum Infect Dis 2014; 1:ofu075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maciejewski JP, Tin RV. Acquired disorders of red cells and white cells. In: Hoffman R, Benz Jr EJ, Silberstein LEet al. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice: Churchill Livingstone; 2009: pp 403. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Delano MJ, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Thayer TC, et al. Neutrophil mobilization from the bone marrow during polymicrobial sepsis is dependent on CXCL12 signaling. J Immunol 2011; 187:911–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kuhns DB, Alvord WG, Gallin JI. Increased circulating cytokines, cytokine antagonists, and E-selectin after intravenous administration of endotoxin in humans. J Infect Dis 1995; 171:145–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Craddock PR, Fehr J, Dalmasso AP, et al. Hemodialysis leukopenia. Pulmonary vascular leukostasis resulting from complement activation by dialyzer cellophane membranes. J Clin Invest 1977; 59:879–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bone RC. Gram-negative sepsis. Background, clinical features, and intervention. Chest 1991; 100:802–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hammerschmidt DE, Craddock PR, McCullough F, et al. Complement activation and pulmonary leukotasis during nylon fiber filtration leukapheresis. Blood 1978; 51:721–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chang JI, Mylotte JM. Pneumococcal bacteremia. Update from an adult hospital with a high rate of nosocomial cases. J Am Geriatr Soc 1987; 35:747–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leroy O, Santré C, Beuscart C, et al. A five-year study of severe community-acquired pneumonia with emphasis on prognosis in patients admitted to an intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med 1995; 21:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Watanakunakorn C, Bailey TA. Adult bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia in a community teaching hospital, 1992–1996. A detailed analysis of 108 cases. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157:1965–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martens P, Worm SW, Lundgren B, et al. Serotype-specific mortality from invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae disease revisited. BMC Infect Dis 2004; 4:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Menéndez R, Torres A, Zalacaín R, et al. Risk factors of treatment failure in community acquired pneumonia: implications for disease outcome. Thorax 2004; 59:960–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marrie TJ, Wu L. Factors influencing in-hospital mortality in community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective study of patients not initially admitted to the ICU. Chest 2005; 127:1260–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]