Abstract

A series of push-pull BODIPYs bearing multiple electron-donating and electron-acceptor groups were synthesized regioselectively from 2,3,5,6,8-pentachloro-BODIPY, and characterized by NMR spectroscopy, HRMS and X-ray crystallography. The influence of the push-pull substituents on the spectroscopic and electrochemical properties of BODIPYs was investigated. Bathochromic shifts were observed for both absorbance (up to 37 nm) and emission (up to 60 nm) in different solvents upon introduction of the push-pull moieties. DFT calculations, consistent with the spectroscopic and cyclic voltammetry studies, show decreased HOMO-LUMO energy gaps upon the installation of the push-pull moieties. BODIPY 7 bearing thienyl groups on the 2 and 6 positions showed the largest λmax for both absorption (635–653 nm) and emission (706–707 nm), but also the lowest fluorescence quantum yields. All BODIPYs were non-toxic in the dark (IC50 > 200 μM) and showed low phototoxicity (IC50 > 100 μM, 1.5 J/cm2) toward human HEp2 cells. Despite the relatively low fluorescence quantum yields, the push-pull BODIPYS were effective for cell imaging, readily accumulating within cells and localizing mainly in the ER and Golgi. Our structure-property studies can guide future design of functionalized BODIPYs for various applications, including bioimaging and in dye-sensitized solar cells.

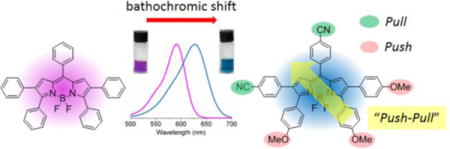

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Push-pull chromophores bearing electron-donor (D) and electron-acceptor (A) groups attached to a π spacer (D-π-A) have been the subject of research interest due to their wide applications in organic light-emitting devices,1 two-photon dyes,2 and dye-sensitized solar cells.3 Among these, porphyrins and phthalocyanines bearing both D and A groups have attracted particular interest in recent decades, as these systems are promising components in dye-sensitized solar cells.3b, 4 Recently, boron dipyrromethenes (BODIPYs) have emerged as π spacers of interest, due to their excellent optical and electrochemical properties that enable their application in various fields, including in biological labeling, drug delivery, sensing, bioimaging, theranostics, and in the field of photovoltaics.5 BODIPYs are strong UV-Vis absorbing dyes and usually emit sharp fluorescence with high fluorescence quantum yields. BODIPYs are also relatively stable in a physiological environment, and display high thermal and photochemical stabilities. In addition, BODIPYs have high structural tunability, which allows manipulation of their physicochemical properties, such as fluorescence quantum yield, water solubility, and redox potential.

The BODIPY core is itself electron deficient (pull), therefore the installation of electron-donating (push) groups onto the BODIPY core provides a push-pull effect within the molecule.6 In recent years, electron-withdrawing groups (pull) have also been introduced onto the BODIPY core to further enhance the pull effect; however, the design, characterization and investigation of BODIPYs bearing both push and pull substituents is so far limited. To date, the push-pull effect has been investigated on three BODIPY platforms of types I, II and III (Figure 1) bearing both electron donor (D) and acceptor (A) moieties.7 In addition, the investigation of push-pull effects on aza-BODIPY platforms has been reported.8

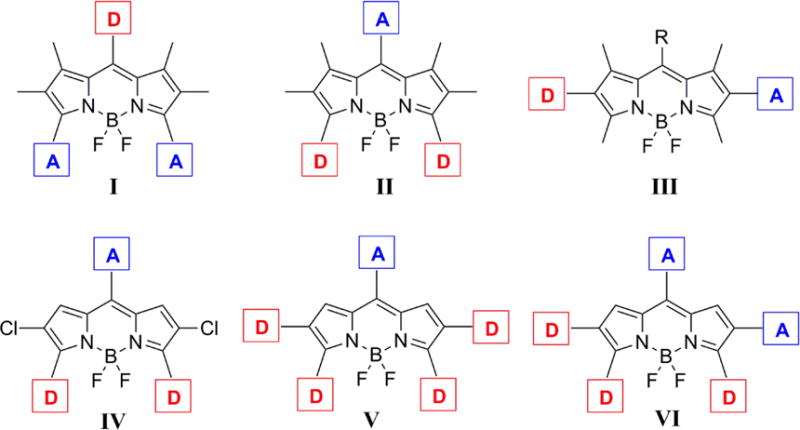

Figure 1.

Platforms of push-pull BODIPYs. D and A represent electron-donor and electron-acceptor groups, respectively (I-III, ref 7c - published by The Royal Society of Chemistry).

The attachment of push and pull moieties to the BODIPY platform can have a dramatic effect on the spectroscopic and electrochemical properties of the molecules.9,8b For example, the presence of an electron-donating group (e.g., 4-aminophenyl) and an electron-withdrawing group (e.g., 4-methoxycarbonylphenyl) on the BODIPY platform can greatly enhance the charge transfer within the molecule, for potential applications in dye-sensitized solar cells,7, 10 and two-photon excitation dyes.2a, 11 These push-pull effects can also significantly red-shift the absorption and emission spectra of BODIPYs to the near-infrared region, therefore making them attractive for biological imaging and biosensing applications.8b For example, a 66 nm bathochromic shift was induced via the introduction of an electron-withdrawing cyano group (-CN) and an electron-donating methoxy group (-OMe) to the para-positions of the 1,7-phenyl and 3,5-phenyl rings of the corresponding tetraphenyl-aza-BODIPY, respectively.8b

The reported DFT electronic structure calculations of a model unsubstituted BODIPY shows large molecular orbital coefficient of the HOMO at the 3,5-positions and large molecular orbital coefficient of the LUMO at the 8-position.12 Therefore, the introduction of electron-donating group(s) at the 3,5-positions and electron-withdrawing group at the 8-position of BODIPYs, as shown in platform II, is expected to have the largest impact on both the spectroscopic and electrochemical properties of this type of dye, by changing the characteristics of the HOMO and LUMO (e.g., lower the energy gaps between HOMO and LUMO).

Herein, we report the design and synthesis of three new push-pull BODIPY platforms (Figure 1, platforms IV, V, VI) bearing multiple push-pull moieties, consisting of 2–4 electron-donor groups and 1–2 electron acceptor(s). The seven new BODIPYs were prepared regioselectively from the same precursor, 2,3,5,6,8-pentachloro-BODIPY (1), using Pd(0)-catalyzed Stille and Suzuki cross-coupling reactions with commercially available reagents. All platforms feature an electron-withdrawing group at the 8-position and electron-donating groups at the 3 and 5 positions. In addition, since the introduction of electron-rich thienyl groups, particularly at the 2 and 6 positions, induces large bathochromic and Stokes’ shifts on BODIPYs,13 two thienyl donors were also installed at the 2 and 6 positions, to give platform V (Figure 1). In order to further investigate the effects of push-pull groups at the 2,6-positions on the spectroscopic and electrochemical properties of BODIPYs, an additional set of push-pull moieties was regioselectively introduced at the 2 and 6 positions to give platform VI (Figure 1). Cyclic voltammetry and DFT calculations were conducted on all the BODIPYs, and a systematic comparison of these platforms with two model BODIPYs (3,5,8-triphenyl- and 2,3,5,6,8-pentaphenyl-BODIPY) was performed to evaluate the influence of the push-pull effect on their spectroscopic and electrochemical properties.

Results and Discussion

1. Synthesis

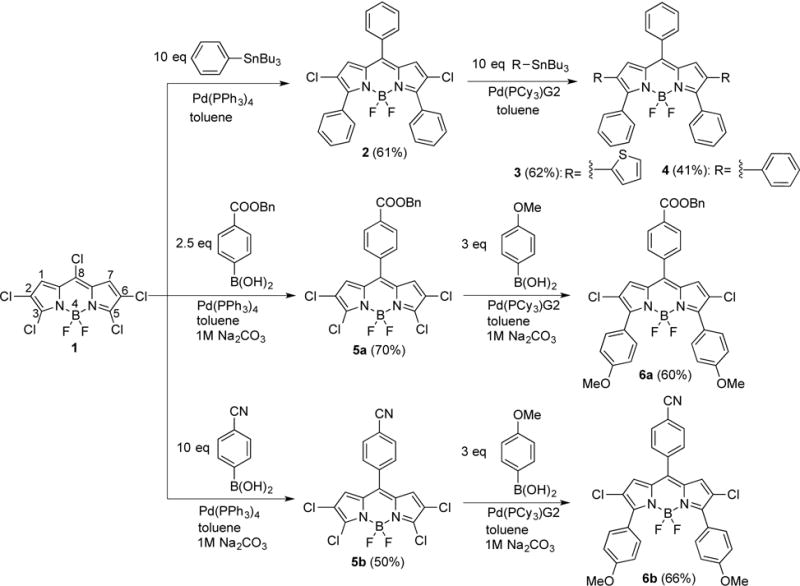

BODIPYs 2, 3, 4, 6a, 6b, 7, and 8 were synthesized by Suzuki or Stille cross-coupling reactions from the same precursor in moderate to good yields, as shown in Schemes 1 and 2. The starting 2,3,5,6,8-pentachloro-BODIPY 1 was prepared from 8-chloro-BODIPY, as previously reported.13a Based on the known regioselectivity of the pentachloro-BODIPY (reactivity order: 8-Cl > 3,5-Cl > 2,6-Cl),13a different functional groups can be introduced at the BODIPY periphery allowing for the design of various push-pull BODIPYs through versatile Pd(0)-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Furthermore, the unsubstituted 1,7-positions of BODIPY 1 are expected to favor relatively small dihedral angles between the substituents and the BODIPY core, potentially leading to increased electronic interactions. In this study, 2-(tributylstannyl)thiophene and/or 4-methoxyphenyl boronic acid were chosen as the electron-donating sources, and 4-benzyloxycarbonylphenyl or 4-cyanophenyl boronic acid were chosen as the electron-withdrawing species to confer the BODIPYs push-pull characteristics. Two electron donor groups were introduced at the 3,5-positions (largest molecular orbital coefficient of the HOMO) and one electron acceptor group was introduced at the 8-position (largest molecular orbital coefficient of the LUMO) of all BODIPY platforms, e.g. platform IV; in addition, two electron donors (platform V) or one donor and one acceptor (platform VI) were introduced at the 2,6-positions. The 4-benzyloxycarbonylphenyl boronic acid, prepared by adapting a reported procedure,14 has the additional advantage of providing functionalization for subsequent conjugation with biomolecules upon debenzylation. BODIPYs 2 and 4 bearing unsubstituted phenyl groups, were also synthesized as model compounds for comparison purposes, using tributylphenylstannane and 3 mol% of Pd(PPh3)4 or Pd(PCy3)G2 in refluxing toluene,34 giving yields of 61% and 41%, respectively (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthetic routes to BODIPYs 2–4, 5a, 5b, 6a and 6b. BODIPY numbering system is given in the structure of 1.

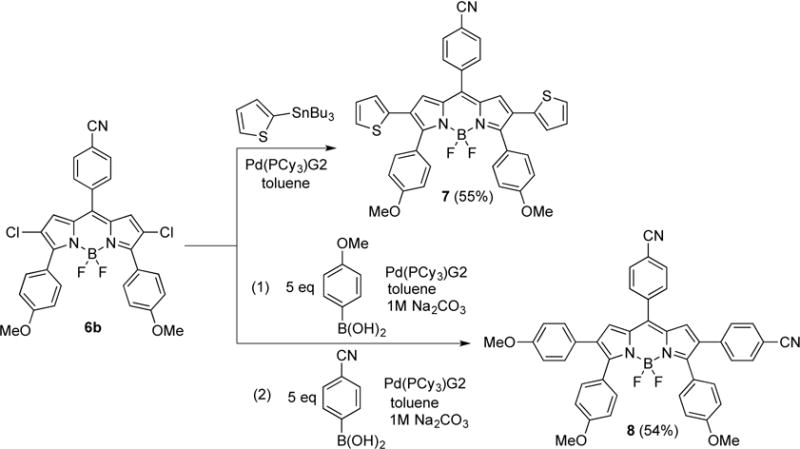

Scheme 2.

Synthetic routes to BODIPYs 7 and 8.

The reaction of 2,3,5,6,8-pentachloro-BODIPY 1 with 2.5 equiv. of 4-benzyloxycarbonylphenyl or with 10 equiv. of 4-cyanophenyl boronic acid, in the presence of 3 mol% of Pd(PPh3)4 and 1 M Na2CO3 (aq) in refluxing toluene, regioselectively produced BODIPYs 5a and 5b in 70% and 50% yields, respectively. Subsequently, BODIPYs 5a and 5b were treated with 3 equiv. of 4-methoxyphenyl boronic acid under similar conditions to regioselectively produce 6a and 6b (platform IV) in 60% and 66% yields, respectively (Scheme 1). BODIPYs 7 (platform V) and 8 (platform VI) were prepared from 6b, using a single Stille reaction, or a two-step Suzuki cross-coupling reaction, in 55% and 54% overall yields, respectively (Scheme 2). Compared with the Pd(PPh3)4 catalyst, Pd(PCy3)G2 greatly increased the yield of the cross-coupling reactions at the 2,6-positions, due to the more reactive complex formed by the bulkier ligands of the Pd(PCy3)G2 catalyst.13a, 15 For comparison purposes, BODIPY 3 was also prepared from 2 using 2-(tributylstannyl)thiophene and Pd(PCy3)G2 in refluxing toluene, in 62% yield. The structures of the new BODIPYs were confirmed by 1H, 13C, and 11B NMR spectroscopy, and by HRMS (see Supporting Information, Figures S1–27).

2. X-ray crystallography

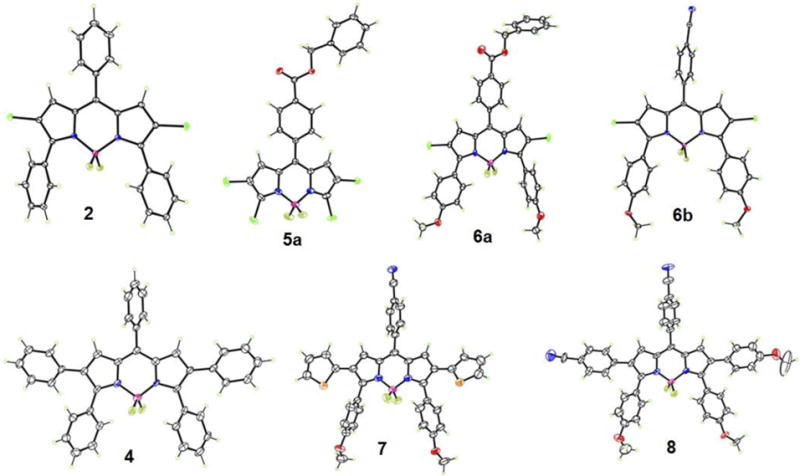

The X-ray crystal structures for BODIPYs 2, 4, 5a, 6a, 6b, 7 and 8 were obtained and are shown in Figure 2. In these structures, the dihedral angles between the 8-aryl substituent and the 12-atom BODIPY core were found to be 62.0, 59.4, 49.7, 56.6, 63.7, 54.1, and 60.7° for 2, 4, 5a, 6a, 6b, 7 and 8, respectively (Figure S28). In the absence of 1,7-substituents, the dihedral angles are significantly smaller (by about 30°) compared with 1,7-substituted BODIPYs (for example in 1,7-dimethyl-BODIPYs) in which the 8-substituent is almost perpendicular with the BODIPY core.13c, 16 This decrease in dihedral angle could lead to better conjugation and electronic communication between the 8-aryl substituent and the BODIPY core, therefore enhancing the push-pull effect. The dihedral angles between the 3,5-aryl substituents and the BODIPY core are also in the range of 45–65° for all the compounds, except for BODIPY 7, which shows dihedral angles of 70.3 and 86.1° (Figure S32), due to the presence of the 2,6-thienyl groups. On the other hand, the dihedral angles between the 2,6-substituents in BODIPYs 4, 7 and 8 and the 12-atom core are somewhat smaller, in the range of 6–44°, particularly for BODIPY 7 with thiophene groups on the 2,6-positions (dihedral angles 6.0 and 27.5°, Figure S29–31). These results suggest that the push-pull moieties on the 2,6-positions as in the case of platform VI could lead to enhanced electronic interactions.

Figure 2.

Crystal structures of BODIPYs 2, 4, 5a, 6a, 6b, 7 and 8 with 50% ellipsoids. Only one orientation is shown for disordered regions in 7 and 8.

In compounds 4, 7, and 8 bearing 2,6-substituents, the C9N2B BODIPY cores are fairly planar, with mean deviations from coplanarity of 0.040, 0.035, and 0.053 Å, respectively. In the compounds having chlorine at the 2,6-positions, the cores are less planar, the central six-membered C3N2B ring having a slight envelope conformation with boron at the flap position. The B atom lies 0.17, 0.14, 0.15 (mean of two), and 0.23 Å out of the plane of the other five atoms for 2, 5a, 6a, and 6b, respectively. The C-Cl bond distances in these BODIPYs are in the 1.681(2) – 1.758(8) Å range.

3. Spectroscopic properties

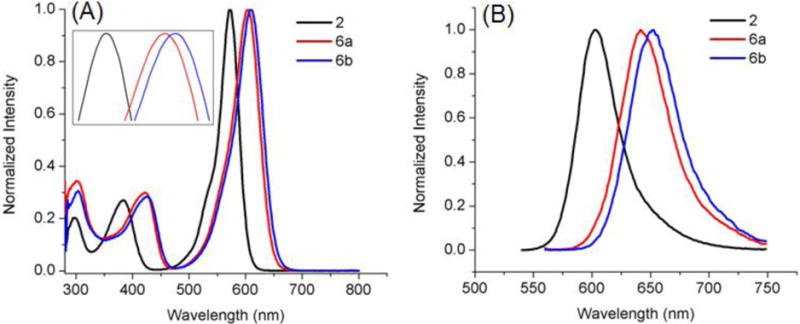

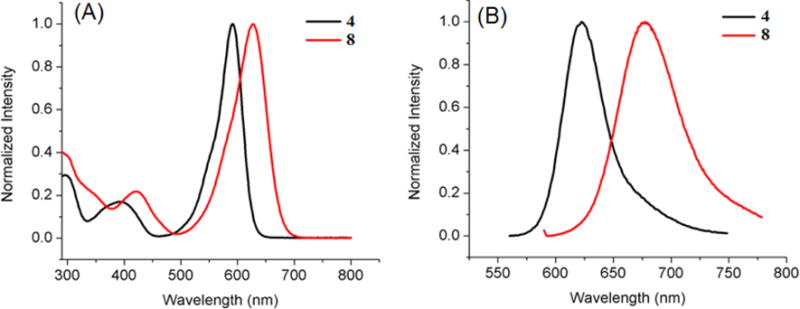

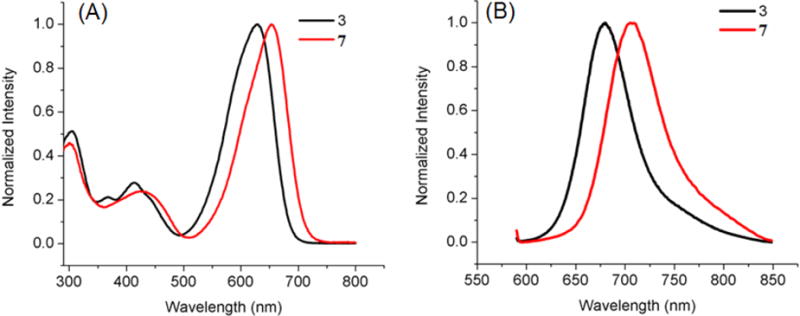

The spectroscopic properties of the push-pull BODIPYs were evaluated in three solvents, in increasing order of polarity: toluene, THF and acetonitrile, and the results are summarized in Table 1 and in Figures 3–5 (see also Figures S33–S39 in the Supporting Information). All compounds show strong S0-S1 transitions with molar absorption coefficients in the range 23,000–72000 M−1 cm−1. Weaker and broader absorption bands centered at around 400 nm were observed at higher energy, which are attributed to S0–Sn (n ≥ 2) transitions of the BODIPY moiety.6c, 9a, 12 In addition, π-π* transitions at 230–320 nm were also observed for all BODIPYs.9a In comparison with the model 3,5,8-triphenyl-BODIPY 2, compounds 6a and 6b bearing electron-donor (-OMe) groups at the para-position of the 3,5-phenyls and an electron-acceptor group (-CO2Bn or –CN) at the para-position of the 8-phenyl group exhibited 25–37 nm and 40–48 nm bathochromic shifts in the absorption and emission bands, respectively (Figure 3). An enhanced pull effect in the case of BODIPY 6b was observed, as this compound displays larger red-shifts for both the absorbance and emission bands compared with 6a. Since the CN group (Hammett parameter σp = 0.66)17 is more electron-withdrawing than the CO2Bn group (Hammett parameter σp = 0.56),17 these parameters are helpful in predicting push-pull effects in BODIPY systems. The introduction of phenyl groups at the 2,6-positions, as in BODIPY 4, further induced bathochromic shifts of 18–20 nm for absorption and 19–28 nm for emission relative to 2; larger red-shifts were observed upon introduction of electron-donating thienyl groups at the 2,6-positions, in the order of 54–56 nm for absorption and 77–95 nm for emission, as previously observed.13a, 18

Table 1.

Spectroscopic properties of BODIPYs in toluene (Tol), tetrahydrofuran (THF) and acetonitrile (CH3CN) at 298 K.

| Cpds. | Solventa | λab(nm) | λem(nm) | Stokes Shift (nm) | ε (L·mol−1·cm−1) | Φfb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tol | 572 | 603 | 31 | 71.3 × 103 | 0.30 | |

| 2 | THF | 566 | 597 | 31 | 67.3 × 103 | 0.13 |

| CH3CN | 558 | 588 | 30 | 51.6 × 103 | 0.12 | |

| Tol | 604 | 643 | 39 | 54.0 × 103 | 0.13 | |

| 6a | THF | 594 | 637 | 43 | 31.8 × 103 | 0.08 |

| CH3CN | 583 | 632 | 49 | 40.2 × 103 | 0.06 | |

| Tol | 609 | 650 | 41 | 50.4 × 103 | 0.09 | |

| 6b | THF | 597 | 643 | 46 | 39.8 × 103 | 0.05 |

| CH3CN | 587 | 636 | 49 | 45.0 × 103 | 0.04 | |

| Toluene | 628 | 680 | 52 | 32.4 × 103 | 0.08 | |

| 3 | THF | 620 | 680 | 60 | 26.3 × 103 | 0.04 |

| CH3CN | 613 | 683 | 70 | 26.0 × 103 | 0.01 | |

| 7 | Toluene | 653 | 707 | 54 | 38.6 × 103 | 0.03 |

| THF | 645 | 706 | 61 | 32.4 × 103 | 0.02 | |

| CH3CN | 635 | 706 | 71 | 33.4 × 103 | <0.01 | |

| Toluene | 592 | 622 | 30 | 67.5 × 103 | 0.64 | |

| 4 | THF | 586 | 620 | 34 | 54.6 × 103 | 0.33 |

| CH3CN | 576 | 616 | 40 | 57.1 × 103 | 0.34 | |

| Toluene | 626 | 677 | 51 | 30.0 × 103 | 0.06 | |

| 8 | THF | 618 | 676 | 58 | 25.2 × 103 | 0.03 |

| CH3CN | 606 | 676 | 70 | 23.2 × 103 | <0.01 |

Solvent polarity (ETN): toluene=0.099; THF=0.207; CH3CN=0.460.19

Figure 3.

Absorbance (A) and fluorescence (B) of BODIPYs 2, 6a and 6b in toluene.

Figure 5.

Absorbance (A) and fluorescence emission (B) of BODIPYs 4 and 8 in toluene.

In all solvents, push-pull BODIPY 7, bearing two thienyl groups at the 2 and 6 positions, shows the longest λmax for absorption (635–653 nm) and emission (706–707 nm), and the largest Stokes shift (54–71 nm) of all BODIPYs in the three solvents. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that the thienyl groups, especially at the 2,6-positions, induce large bathochromic shifts in the absorption and emission bands, and enhanced Stokes shifts on BODIPYs.13a, 13c, 16 The larger Stokes shifts are presumably due to the geometry difference between the S0 and S1 states upon excitation, resulting in increased geometry relaxation.16, 21 In comparison with 3, BODIPY 7 shows bathochromic shifts of 22–25 nm for absorption and 23–27 nm for emission, induced by the electron-donor 3,5-p-methoxyphenyl groups and the electron-acceptor 8-p-cyanophenyl group (Figure 4). On the other hand, the introduction of additional electron-donor and acceptor moieties, as in BODIPY 8, induced greater bathochromic shifts, in the order of 30–34 nm for absorption and 55–60 nm for emission, in comparison with 4 (Figure 5). These results show that the number and electronic nature of substituents on the BODIPY platform induce bathochromic shifts of different extent, and are complemented by the electrochemistry and DFT studies discussed below.

Figure 4.

Absorbance (A) and fluorescence (B) of BODIPYs 3 and 7 in toluene.

As the polarity of the solvent increases from toluene (ETN=0.099) to THF (ETN=0.207) and to acetonitrile (ETN=0.460),19 the observed λmax generally decreased for both absorption (6–22 nm) and emission (0–15 nm), along with a gradual decrease in the relative fluorescence quantum yields. The decrease in λmax is probably due to a decrease in the dipole moment of the BODIPY upon excitation, associated with the intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) between the donor and acceptor (μg > μe, where μg and μe are the ground and excited state dipole moments), indicating that the ground state is better stabilized by the polar solvents.19, 22 The decreased quantum yield with increase solvent polarity is consistent with previous observations, and is attributed to the increase of nonradiative decay in more polar solvents.8b, 9a, 9c, 9d, 23 A 2–4 fold decrease in fluorescence quantum yields was observed by comparing BODIPYs 2 to 6a and 6b, 3 to 7, and 4 to 8, which can be attributed to the ICT between donors and acceptors9b, 10 and the internal conversion between narrower band gaps.24 ICT is known to influence the rate of nonradiative relaxation of fluorophores, resulting in decreased fluorescence quantum yields.25 Another possible reason for the low fluorescence quantum yields observed for BODIPYs 3 and 7 is the greater freedom of rotation of the small thienyl groups in comparison with phenyl, which increases the energy lost to nonradiative decay.16 Interestingly, the quantum yield for BODIPY 8 decreased dramatically, 11–48 fold in the different solvents compared with BODIPY 4, which could be due to enhanced ICT resulting from the multiple sets of push-pull moieties in this compound. On the other hand, the Stokes shift increased for all the compounds as the polarity of the solvent increased. Among the different BODIPYs, the Stokes shift for 8 increased the most (19 nm) upon going from toluene to acetonitrile, indicating a large difference in dipole moment between the ground and excited states.9a, 23

4. Electrochemistry

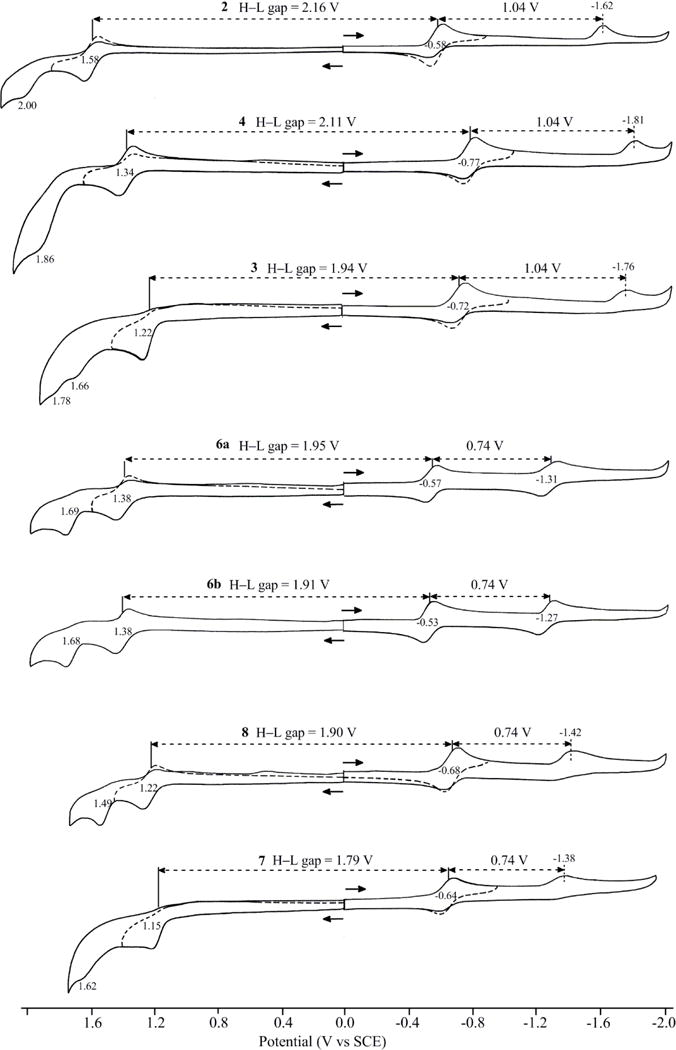

The electrochemistry of the seven push-pull BODIPYs was investigated in three different solvents, THF, PhCN and CH3CN, with similar results being obtained in all cases. Each BODIPY undergoes two one-electron reductions and two one-electron oxidations, with the exact potential depending upon the type and location of the electron donor and/or electron acceptor group on the molecule. A summary of the measured potentials in PhCN, 0.1M TBAP is given in Table 2 (the potential data in CH3CN and THF are given in Table S1 of the Supporting Information) and examples of cyclic voltammograms are shown in Figure 6 which are arranged according to the HOMO-LUMO gap that varied in magnitude between 2.16 V in the case of BODIPY 2 and 1.79 V in case of BODIPY 7. The HOMO-LUMO gap obtained by cyclic voltammetry decreased after introduction of the push and pull groups into the BODIPY platforms, from 2 to 6a and 6b, from 3 to 7, and from 4 to 8, consistent with the trend of the corresponding maximum absorption and emission wavelengths obtained in the spectroscopic studies (Table 1, Figures 3–5). All BODIPYs were characterized by well-defined redox reactions and an overall mechanism is shown in Scheme 3.

Table 2.

Half-wave potentials (V vs. SCE) for BODIPYs 2, 3, 4, 6a, 6b, 7 and 8 in PhCN with 0.1 M TBAP .

| Oxidation (V)

|

Reduction (V)

|

H-L (V) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BODIPY | 2nd | 1st | 1st | 2nd | Δ (2–1) (V) | Gapb |

| 2 | 2.00a | 1.58 | −0.58 | −1.62a | 1.04 | 2.16 |

| 3 | 1.66a | 1.22 | −0.72 | −1.76a | 1.04 | 1.94 |

| 4 | 1.86a | 1.34 | −0.77 | −1.81a | 1.04 | 2.11 |

| 6a | 1.69 | 1.38 | −0.57 | −1.31 | 0.74 | 1.95 |

| 6b | 1.68 | 1.38 | −0.53 | −1.27 | 0.74 | 1.91 |

| 7 | 1.62a | 1.15 | −0.64 | −1.38a | 0.74 | 1.79 |

| 8 | 1.49 | 1.22 | −0.68 | −1.42a | 0.74 | 1.90 |

Peak potential, Ep at scan rate of 0.1 V/s;

HOMO - LUMO Gap = |E1/2 (1st Ox) − E1/2 (1st Red)|.

Figure 6.

Cyclic voltammograms for BODIPYs 2, 3, 4, 6a, 6b, 7 and 8 in PhCN with 0.1 M TBAP.

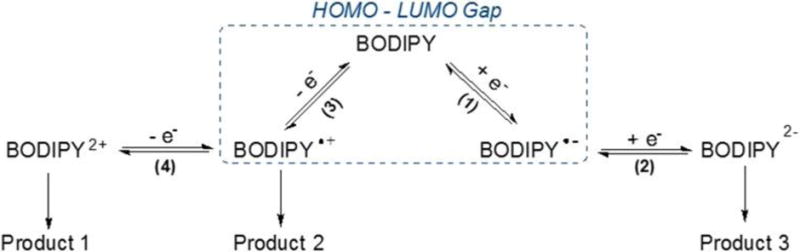

Scheme 3.

Proposed redox reaction mechanisms of BODIPYs.

The first one-electron reductions of the push-pull BODIPYs are facile and generate a π-anion radical at E1/2 values of −0.53 to −0.58 V in the case of compounds 2, 6a and 6b, −0.64 or −0.68 V in the case of compounds 7 and 8, and −0.72 or −0.77 V in the case of compounds 3 and 4. All of these reductions are substantially easier (occur at more positive potentials) than for reduction of previously synthesized BODIPYs lacking the current set of push-pull substituents.26 A second one-electron addition is also seen for these BODIPYs. This reduction is assigned to the formation of a BODIPY dianion and occurs at a potential which is located 1.04 or 0.74 V more negative than E1/2 for the first reduction, as shown in Figure 6. The second one-electron addition is followed by a rapid chemical reaction for five of the seven investigated BODIPYs but it is reversible and well-defined for 6a and 6b. To the best of our knowledge, these two compounds are the only monomeric BODIPYs reported to undergo two reversible one-electron reductions.26–27 The first one-electron oxidation is also reversible for five of the seven investigated BODIPYs, the only exceptions being for compounds 3 and 7 where a rapid chemical reaction followed electron transfer. The initial electrooxidation is assigned as generating a BODIPY π-cation radical and this process is followed by a second irreversible oxidation at more positive potentials, as shown in Figure 6. The nature of the chemical reactions coupled to the electron transfer was not investigated in the current study but are probably associated with radical coupling and dimer formation as previously reported for other BODIPYs.26

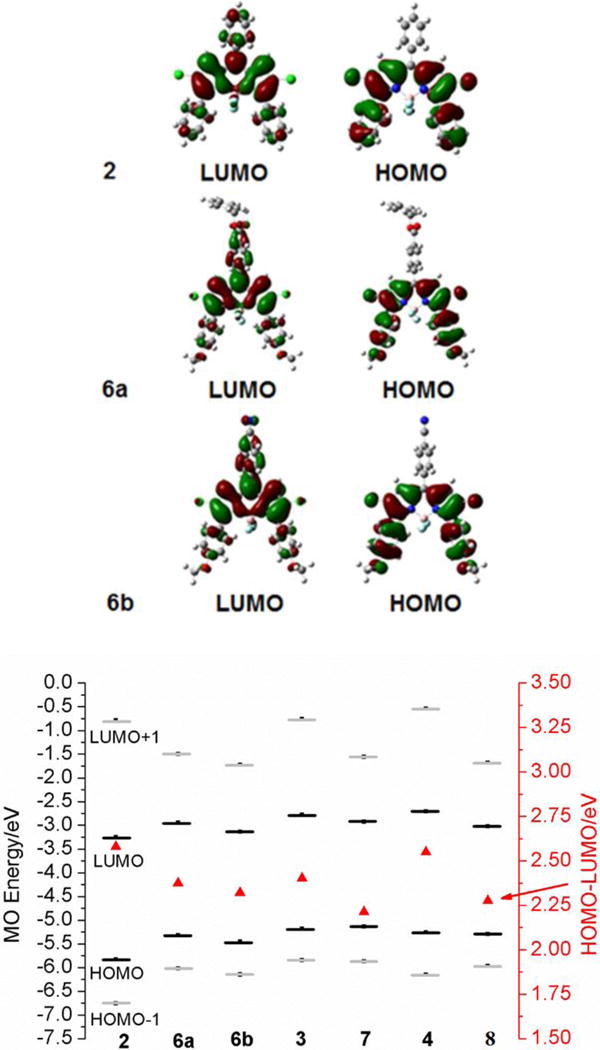

5. DFT Calculations

To provide further insight into the spectroscopic and electrochemical properties of the push-pull BODIPYs, DFT calculations were conducted and the results are summarized in Figure 7, and Table S2/Figure S40 of the Supporting Information. With the installation of the electron-donating (-OMe) and electron-withdrawing (-CN and –CO2Bn) groups to, respectively, the 3,5- and 8-para-phenyl positions, the molecular orbital coefficient on the HOMO is shifted to the substituents bearing the electron-donating groups, whereas the molecular orbital coefficient on the LUMO is shifted to the 8-position bearing the electron-withdrawing group (Figures 7 and S40). As a result, the overall HOMO-LUMO gap decreases by approximately 0.2 eV after the introduction of the push-pull moieties, from 2 to 6a and 6b, from 3 to 7, and from 4 to 8 (Table S2, Figure 7). This trend in the HOMO-LUMO gap (2 > 6a and 6b, 3 > 7, 4 > 8) is consistent with the results obtained from cyclic voltammetry (Table 2) and from the spectroscopic studies (Table 1).

Figure 7.

DFT calculated frontier orbitals for BODIPY 2, 6a and 6b (upper) and molecular orbital energies for BODIPYs. The HOMO-LUMO gaps are plotted against a secondary axis and are denoted by red triangles (bottom).

6. Studies in human HEp2 cells

The concentration-dependent dark and phototoxicity (1.5 J/cm2 light dose), and the time-dependent cellular uptake of BODIPYs 2, 3, 4, 6a, 6b, 7 and 8 were evaluated in HEp2 cells, and the results are summarized in Table 3, Figures 8–10 and S41–42 of the Supporting Information. None of the BODIPYs were found to be cytotoxic in the dark up to 200 μM concentration, nor upon light irradiation (1.5 J/cm2) up to 100 μM concentration. BODIPY 4 was the only compound that showed slight phototoxicity (Figure S42 of the Supporting Information), but still with IC50 above 100 μM. These results are in agreement of previous reports on the low cytotoxicity of BODIPYs, in part due to their usually low quantum yields for triplet state formation.28

Table 3.

Dark and phototoxicity and cellular uptake of BODIPYs using human HEp2 cells.

| Compd. | Dark toxicity IC50 (μM) | Phototoxicity IC50 (μM) | Cellular uptake at 24 h (nM/cell) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | >200 | >100 | 1.2±0.10 |

| 6a | >200 | >100 | 0.14±0.01 |

| 6b | >200 | >100 | 0.51±0.01 |

| 3 | >200 | >100 | 0.14±0.01 |

| 7 | >200 | >100 | 0.12±0.01 |

| 4 | >200 | >100 | 0.058±0.028 |

| 8 | >200 | >100 | 0.79±0.13 |

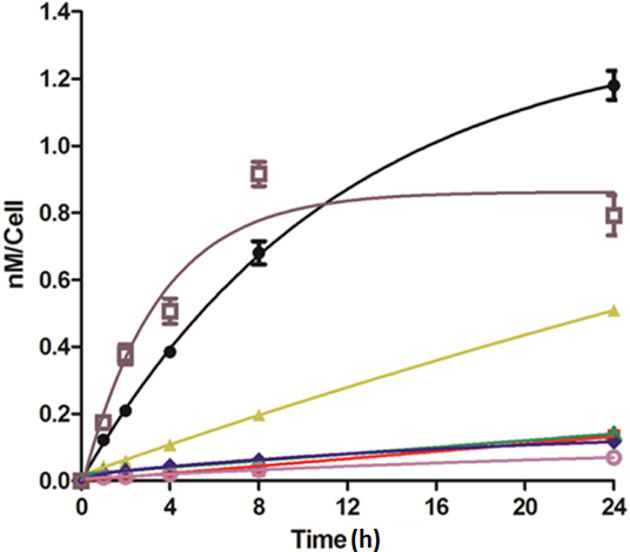

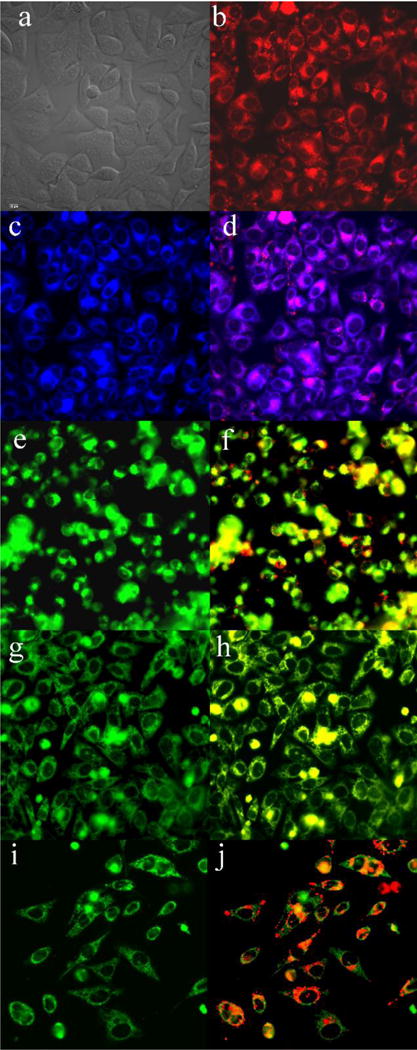

Figure 8.

Time-dependent uptake of BODIPYs 2 (black), 6a (red), 6b (yellow), 3 (green), 4 (pink), 7 (blue) and 8 (brown) in human HEp2 cells at 10 μM concentration.

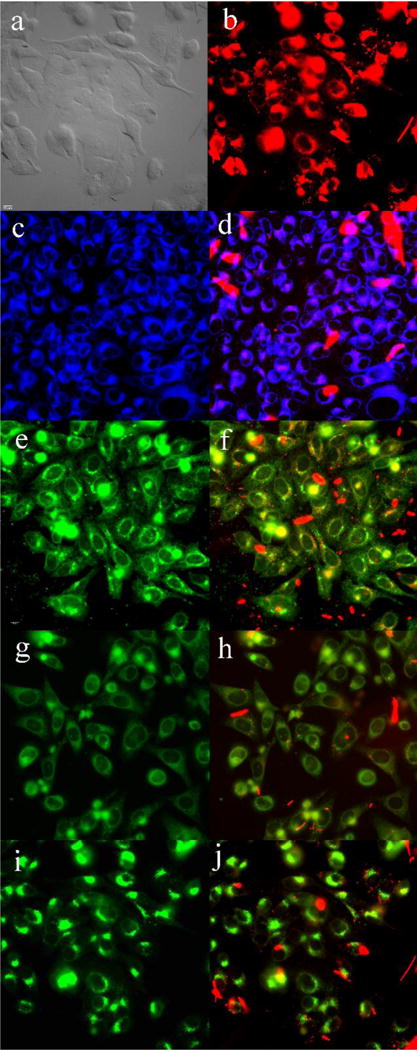

Figure 10.

Subcellular localization of 8 in HEp2 cells at 10 μM for 6 h. (a) phase contrast, (b) overlay of 8 and phase contrast, (c) ER Tracker Blue/White, (d) overlay of 8 and ER Tracker, (e) BODIPY Ceramide, (f) overlay of 8 and BODIPY Ceramide, (g) MitoTracker Green, (h) overlay of 8 and MitoTracker, (i) LysoSensor Green, (j) overlay of 8 and LysoSensor Green. Scale bar: 10 μm.

The cellular uptake of all BODIPYs generally increased with time as shown in Figure 8. Among the BODIPYs, 2 and 8 were taken-up faster and more efficiently at all times investigated, particularly in the first 4 hours, after which a slower uptake was observed and, in the case of 8, a plateau was reached after 8 hours. BODIPY 3, 4, 6a, and 7 exhibited very low uptake in HEp2 cells, which could be due to their high hydrophobicity and poor water solubility. The higher cellular uptake observed for 6b and 8 compared with the other compounds could be due to the introduction of the polar –OMe and –CN groups which enhances their polarity and water solubility. It is interesting to note that the dichloro-triphenyl-BODIPY 2 accumulated the most within cells after 24 hours, whereas the least polar and most hydrophobic pentaphenyl-BODIPY 4 accumulated the least.

Fluorescence microscopy was conducted using HEp2 cells to investigate the main subcellular localization sites of the BODIPYs. The organelle-specific probes used in the overlay experiments are LysoSensor Green (lysosomes), MitoTracker Green (mitochondria), ER Tracker Blue/White (endoplasmic reticulum) and BODIPY Ceramide (Golgi). The results are shown in Figures 9 and 10 for push-pull BODIPYs 6b and 8 that accumulated most efficiently within cells, and in Figures S43–45 of the Supporting Information for 2, 3, 4, 6a and 7. All BODIPYs were observed in multiple organelles (see Table S3 of the Supporting Information), the major localization sites are the cell ER, lysosomes, mitochondria, and the Golgi apparatus, in agreement with previously reported studies.28a, 28b

Figure 9.

Subcellular localization of 6b in HEp2 cells at 10 μM for 6 h. (a) phase contrast, (b) overlay of 6b and phase contrast, (c) ER Tracker Blue/White, (d) overlay of 6b and ER Tracker, (e) BODIPY Ceramide, (f) overlay of 6b and BODIPY Ceramide, (g) MitoTracker Green, (h) overlay of 6b and MitoTracker, (i) LysoSensor Green, (j) overlay of 6b and LysoSensor Green. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Conclusions

A series of push-pull BODIPYs were synthesized in good yields from a single 2,3,5,6,8-pentachloro-BODIPY (1), via regioselective Suzuki and Stille cross-coupling reactions. The structures of all the compounds were confirmed by HRMS, NMR spectroscopy, and X-ray crystallography. A systematic study was performed before and after installation of electron-withdrawing (at the 8-position and, in one case also at the 2-position), and electron-donating (at the 3,5-, 2,3,5- and 2,3,5,6-positions) groups, to investigate the influence of the push-pull effect on their spectroscopic and electrochemical properties. Bathochromic shifts were observed in both absorbance (up to 37 nm) and emission (up to 60 nm) in solvents with different polarities after the installation of electron-donor and acceptor groups. DFT calculations indicate that the HOMO-LUMO energy gap decreases with the installation of the push-pull moieties. The trend of the DFT calculated HOMO-LUMO energy was found to be: (1) 2 > 6a and 6b; (2) 3 > 7; (3) 4 > 8, which is consistent with the HOMO-LUMO trend observed experimentally from cyclic voltammetry. BODIPY 4 bearing thienyl groups at the 2 and 6 positions exhibits the longest λmax for absorption (635–653 nm) and emission (706–707 nm) and the largest Stokes shift (54–71 nm) in all solvents investigated. On the other hand, the fluorescence quantum yield decreased up to 48-fold after the introduction of the push-pull moieties, probably due to ICT between donor and acceptor, and nonradiative decay. All BODIPYs showed well-defined redox reactions, and no dark cytoxicity (IC50 > 200 μM) nor phototoxicity (IC50 > 100 μM, 1.5 J/cm2) in human HEp2 cells. Among the push-pull BODIPYs, compounds 6b and 8 showed the highest cellular uptake. Despite the relatively low fluorescence quantum yields, the push-pull BODIPYs were efficient in in cell imaging investigations, and localized in multiple cell organelles, including the ER, Golgi, lysosomes, and mitochondria.

Experimental Section

1. Synthesis

All commercial available reagents and solvents were used as received. Reactions were monitored by analytical TLC (precoated, polyester backed, 60 Å, 0.2 mm). Purifications by column chromatography used silica gel (230–400 mesh, 60 Å), and preparative TLC plates. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained on the NMR spectrometers (400 MHz or 500 MHz for 1H NMR and 100 MHz or 125MHz for 13C NMR) at 300 K. 11B NMR spectra were obtained on a NMR spectrometer with 128 MHz, using BF3•OEt2 as external reference. Chemical shifts (δ) are given in parts per million (ppm) in CDCl3 (7.27 ppm for 1H NMR, 77.0 ppm for 13C NMR) and coupling constants (J) are given in Hz. All high resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained on a ESI-TOF mass spectrometer. Melting points were measured using a capillary melting point apparatus equipped with a thermometer. Crystal structures were determined using data collected at low temperature (90K) on a diffractometer equipped with a focusing monochromator for the Mo X-ray beam, a Cu microfocus X-ray source, and an chiller.

1.1. General procedure for Suzuki cross-coupling reactions

The starting BODIPY was added to a 15 mL round-bottomed flask followed by the addition of either 3 mol% of Pd(PPh3)4 (for 5a, 5b) or Pd(PCy3)G2 (for 6a, 6b and 8). The flask was evacuated and refilled with nitrogen three times, before toluene (4 mL) and 1M Na2CO3 (aq) (1 mL) were added to the mixture. Boronic acids were added portion-wise, and the reaction mixture was stirred and heated under nitrogen at 90–100 °C. The reaction was monitored by analytical TLC every 30–60 min. Water (20 mL) was added to the reaction mixture, and dichloromethane (10 mL × 3) was used for extraction of the organic components. The organic layers were combined, washed with aqueous saturated brine, then water, and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was removed under vacuum, and the resulting residue was purified by column chromatography using dichloromethane/hexanes or ethyl acetate/hexanes as the elution solvents.

1.1.1. 2,3,5,6,8-Pentachloro-BODIPY (1) was prepared as previously reported.13a

2,3,5,6,8-Pentachloro-BODIPY (1) was prepared as previously reported.13a

1.1.2. 8-(4-Benzyloxycarbonylphenyl)-2,3,5,6-tetrachloro-BODIPY (5a)

This BODIPY was prepared from 1 (20.0 mg, 0.055 mmol) and 2.5 eq of 4-benzyloxycarbonylphenyl boronic acid (35.2 mg, 0.14 mmol), yielding 20.8 mg, 70% of BODIPY 5a as a red solid: mp 186–188 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) = 8.26–8.28 (m, 2H), 7,57–7.59 (m, 2H), 7.42–7.51 (m, 5H), 6.79 (s, 2H), 5.45 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ (ppm) = 166.2, 143.9, 142.2, 135.8, 235.5, 132.9, 131.2, 130.3, 130.1, 128.7, 128.6, 128.3, 127.9, 122.3, 67.4; 11B NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz) δ (ppm) = −0.24–0.18 (t, J(B,F) = 26.4 Hz); HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z calculated for C23H13BCl4F2N2O2: 536.9834; found: 536.9809 [M−].

1.1.3. 8-(4-Cyanophenyl)-2,3,5,6-tetrachloro-BODIPY (5b)

This BODIPY was prepared from (1) (11.4 mg, 0.031 mmol) and 10 eq of 4-cyanophenyl boronic acid (46.0 mg, 0.32 mmol), yielding 6.7 mg, 50% of BODIPY 5b as red solid: mp 280–282 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) = 7.89–7.90 (m, 2H), 7.62–7.64 (m, 2H), 6.76 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ (ppm) = 144.6, 140.6, 135.9, 132.6, 131.0, 130.8, 127.6, 122.7, 117.4, 115.3; 11B NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz) δ (ppm) = −0.26–0.15 (t, J(B,F) = 26.7 Hz); HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z calcd for C16H6BCl4F2N3: 427.9419; found: 427.9412 [M−].

1.1.4. 8-(4-Benzyloxycarbonylphenyl)-3,5-di(4-methoxyphenyl)-2,6-dichloro-BODIPY (6a)

This BODIPY was prepared from (5a) (12.9 mg, 0.024 mmol) and 10 eq of 4-methoxyphenyl boronic acid (10.9 mg, 0.072 mmol), yielding 9.8 mg, 60% of BODIPY 6a as a dark blue solid: mp 233–235 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ (ppm) = 8.28–8.29 (m, 2H), 7.66–7.69 (m, 6H), 7.51–7.53 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.47 (m, 3H), 6.98–6.99 (m, 4H), 6.82 (s, 2H), 3.87 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ (ppm) = 165.5, 161.0, 155.2, 137.9, 135.7, 132.6, 132.1, 132.0, 130.4, 129.9, 128.7, 128.5, 128.3, 127.8, 123.2, 121.4, 113.6, 67.2, 55.3; 11B NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz) δ (ppm) = 0.35–0.82 (t, J(B,F) =30.7 Hz); HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z calcd for C37H27BCl2F2N2O4: 681.1451; found: 681.1450 [M−].

1.1.5. 8-(4-Cyanophenyl)-3,5-di(4-methoxyphenyl)-2,6-dichloro-BODIPY (6b)

This BODIPY was prepared from (5b) (8.5 mg, 0.02 mmol) and 10 eq of 4-methoxyphenyl boronic acid (30.0 mg, 0.2 mmol), yielding 7.5 mg, 66% of BODIPY 6b as dark blue solid: mp 288–290 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ (ppm) = 7.87–7.89 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.66–7.71 (m, 6H), 6.97–6.98 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 4H), 6.76 (s, 2H), 3.86 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ (ppm) = 161.1, 155.7, 139.6, 138.0, 132.3, 132.0, 131.0, 128.0, 127.5, 123.6, 121.2, 117.8, 114.5, 113.6, 55.3; 11B NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz) δ (ppm) = 0.35–0.82 (t, J(B,F) =30.6 Hz); HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z calcd for C30H20BCl2F2N3O2: 572.1035; found: 572.1026 [M−].

1.1.6. 8-(4-Cyanophenyl)-3,5-di(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-6-(4-cyanophenyl)-BODIPY (8)

This BODIPY was prepared from (6b) (8.1 mg, 0.0141 mmol), 5 eq of 4-methoxyphenyl boronic acid (10.7 mg, 0.0707 mmol). The crude product then reacted with 5 eq of 4-cyanophenyl boronic acid (10.4 mg, 0.0707 mmol), yielding 5.4 mg, 54% of BODIPY 8 as dark blue solid: mp (273–275 °C); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ (ppm) = 7.90–7.88 (m, 2H), 7.78–7.80 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.47 (m, 4H), 7.38–7.40 (m, 2H), 7.12–7.10 (M, 2H), 6.93–6.95 (M, 2H), 6.83–6.89 (m, 6H), 6.73–6.75 (m, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 3.77 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ (ppm) = 160.8, 160.5, 160.0, 159.1, 155.2, 139.4, 138.9, 138.8, 136.5, 134.9, 133.7, 132.3, 132.1, 132.0, 131.9, 131.1, 129.6, 128.7, 128.1, 126.6, 125.7, 123.4, 123.3, 118.9, 118.0, 114.2, 113.8, 113.8, 113.6, 110.2, 55.3, 55.2; 11B NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz) δ (ppm) = 0.68–1.15 (t, J(B,F) =30.5 Hz); HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z calcd for C44H31BF2N4O3: 711.2499; found: 711.2482 [M−].

1.2. General procedure for Stille cross-couplings reactions

The starting BODIPY was added to a 15 mL round-bottomed flask followed by the organotin reagent, 3% mol of Pd(PPh3)4 (for 2) or Pd(PCy3)G2 (for 3, 4, 7). The flask was evacuated and refilled with nitrogen three times. Toluene (5 mL) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred and heated at 90–100 °C under nitrogen. Analytical TLC was used to monitor the reaction every 30–60 min. After completion, toluene was removed under vacuum, and the resulting residue was purified by column chromatography using dichloromethane/hexanes or ethyl acetate/hexanes as the elution solvents.

1.2.1. 3,5,8-Triphenyl-2,6-dichloro-BODIPY (2)

This BODIPY was prepared from (1) (10.5 mg, 0.0288 mmol) and 10 eq of tributylphenylstannane (106 mg, 0.288 mmol), yielding 8.6 mg, 61% of BODIPY (2) as a purple solid: mp 215–217 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) = 7.58–7.68 (m, 9H), 7.44–7.45 (m, 6H), 6.91 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ (ppm) = 155.0, 144.6, 133.4, 133.0, 130.9, 130.4, 130.2,130.2, 130.0, 129.2, 128.7, 128.4, 127.9, 123.0, 122.9; 11B NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz) δ (ppm) = 0.27–0.74 (t, J(B,F) = 29.9 Hz); HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z calcd for C27H17BCl2F2N2: 487.0872; found: 487.0868 [M−].

1.2.2. 3,5,8-Triphenyl-2,6-dithienyl-BODIPY (3)

This BODIPY was prepared from (2) (12.4 mg, 0.0254 mmol) and 10 eq of 2-(tributylstannyl)thiophene (94.6 mg, 0.254 mmol), yielding 9.2 mg, 62% of BODIPY (3) as a dark blue solid: mp 178–180 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ (ppm) = 7.72–7.70 (m, 2H), 7.68–7.62 (m, 3H), 7.54–7.53 (m, 4H), 7.46–7.39 (m, 6H), 7.10–7.09 (dd, J = 5.1, 1.1 Hz, 2H), 7.01 (s, 2H), 6.84–6.82 (dd, J = 5.1, 3.6 Hz, 2H), 6.56–6.55 (dd, J = 3.7, 1.1 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ (ppm) = 156.2, 144.27, 135.8, 134.5, 134.1, 131.4, 130.6, 130.5, 130.2, 129.5, 128.6, 128.1, 128.0, 127.2, 126.8, 125.1, 124.7; 11B NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz) δ (ppm) = 0.44–0.90 (t, J(B,F) = 29.7 Hz); HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z calcd for C35H23BF2N2S2: 564.1411; found: 564.142 [M-F]+.

1.2.3. 2,3,5,6,8-Pentaphenyl-BODIPY (4)

This BODIPY was prepared from (2) (13.0 mg, 0.0266 mmol) and 10 eq of tributylphenylstannane (97.6 mg, 0.266 mmol), yielding 6.2 mg, 41% of BODIPY (4) as a dark blue solid: mp 273–275 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) = 7.71–7.73 (m, 2H), 7.58–7.66 (m, 3H), 7.50–7.52 (m, 4H), 7.32–7.39 (m, 6H), 7.17–7.19 (m, 6H), 7.03 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ (ppm) = 156.5, 143.9, 134.7, 134.4, 133.9, 131.8, 130.7, 130.4, 130.3, 129.1, 128.6, 128.4, 128.3, 128.2, 127.9, 126.9; 11B NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz) δ (ppm) = 0.69–1.16 (t, J(B,F) = 30.4 Hz); HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z calcd for C39H27BF2N2Na: 594.2164; found: 594.2147 [M+Na]+.

1.2.4. 8-(4-Cyanophenyl)-3,5-di(4-methoxyphenyl)-2,6-dithienyl-BODIPY (7)

This BODIPY was prepared from (6b) (9.6 mg, 0.0167 mmol) and 10 eq of 2-(tributylstannyl)thiophene (62.4 mg, 0.167 mmol), yielding 6.2 mg, 55% of BODIPY 7 as a dark blue solid: mp 268–270 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ (ppm) =7.93 (m, 2H), 7.81 (m, 2H), 7.49–7.48 (m, 4H), 7.14 (dd, J = 5.1, 1.1 Hz, 2H), 6.94 (m, 4H), 6.87 (dd, J = 5.1, 3.6 Hz, 2H), 6.84 (s, 2H), 6.62 (dd, J = 3.7, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 3.86 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ (ppm) = 160.7, 157.2, 139.8, 138.7, 135.5, 134.0, 132.3, 131.8, 131.1, 128.7, 127.3, 125.9, 125.4, 125.0, 123.2, 118.1, 114.2, 113.6, 55.2; 11B NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz) δ (ppm) = 0.47–0.94 (t, J(B,F) = 29.8 Hz); HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z calcd for C38H26BFN3O2S2: 649.1574; found: 649.1546 [M-F]+.

2. Crystallography

Crystal structures were determined using data collected at T=90K on a diffractometer. MoKα radiation was used for 2, 4, 5a, 6a, and 6b, while CuKα was used for 7 and 8. Compound 5a exhibited a small amount (ca. 10%) of rotational disorder which was evident from partially-populated secondary sites for all the Cl atoms. Compound 6a was a twin and has two molecules in the asymmetric unit. Compound 7 had both thiophenes disordered into two orientations, with relative occupations 70:30 and 80:20. It also had disordered solvent, which was removed using the SQUEEZE procedure. Compound 8 had one methoxy group disordered into 54:46 orientations and also had disordered solvent removed by SQUEEZE. Crystal Data: 2, C27H17BCl2F2N2, monoclinic, a = 15.5375(10), b = 6.0426(4), c = 23.7983(16) Å, β = 93.080(3)°, space group P21/c, Z = 4, 48,015 reflections measured, θmax = 36.5°, 10,891 unique (Rint = 0.052), final R = 0.041 (8237 I>2σ(I) data), wR(F2) = 0.109 (all data), CCDC 1509815; 4, C39H27BF2N2, monoclinic, a = 27.801(3), b = 8.5828(11), c = 25.471(4) Å, β = 105.021(10)°, space group C2/c, Z = 8, 16,414 reflections measured, θmax = 23.3°, 4177 unique (Rint = 0.115), final R = 0.077 (2159 I>2σ(I) data), wR(F2) = 0.218 (all data), CCDC 1509816; 5a, C23H13BCl4F2N2O2, monoclinic, a = 13.7912(4), b = 10.6546(4), c = 15.2354(6) Å, β = 99.863(2)°, space group P21/n, Z = 4, 24,073 reflections measured, θmax = 31.0°, 7034 unique (Rint = 0.035), final R = 0.045 (5519 I>2σ(I) data), wR(F2) = 0.130 (all data), CCDC 1509817; 6a, C37H27BCl2F2N2O4, triclinic, a = 13.0943(15), b = 13.8006(16), c = 17.659(2) Å, α = 83.546(7), β = 83.396(7), γ = 80.198(7)°, space group P-1, Z = 4, 27,197 reflections measured, θmax = 24.0°, 16,564 unique (Rint = 0.119), final R = 0.093 (8684 I>2σ(I) data), wR(F2) = 0.264 (all data), CCDC 1509818; 6b, C30H20BCl2F2N3O2, triclinic, a = 6.4378(3), b = 13.1056(7), c = 15.3828(8) Å, α = 84.902(2), β = 79.560(2), γ = 84.620(2)°, space group P-1, Z = 2, 14,444 reflections measured, θmax = 28.3°, 5922 unique (Rint = 0.030), final R = 0.038 (4794 I>2σ(I) data), wR(F2) = 0.092 (all data), CCDC 1509819; 7, C38H26BF2N3O2S2, triclinic, a = 9.8322(8), b = 13.3203(11), c = 15.0587(12) Å, α = 72.208(6), β = 74.473(6), γ = 81.456(6)°, space group P-1, Z = 2, 19,146 reflections measured, θmax = 62.8°, 5632 unique (Rint = 0.074), final R = 0.062 (3310 I>2σ(I) data), wR(F2) = 0.170 (all data), CCDC 1509820; 8, C44H31BF2N4O3. CHCl3, triclinic, a = 10.3829(9), b = 14.3659(14), c = 15.0975(14) Å, α = 75.674(7), β = 89.346(7), γ = 78.359(7)°, space group P-1, Z = 2, 19,963 reflections measured, θmax = 68.4°, 7279 unique (Rint = 0.061), final R = 0.105 (5062 I>2σ(I) data), wR(F2) = 0.341 (all data), CCDC 1509821.

3. Spectroscopic Studies

All UV-visible and fluorescence spectra were collected on a UV spectrometer and a luminescence spectrometer at 298 K, respectively. A 10 mm path length quartz cuvette and spectroscopic solvents were used for all the measurements. Molar absorption coefficients (ε) were determined from the slope of absorbance vs concentration of five dilute solutions with absorbance in the range of 0.2–1.0. Fluorescence quantum yields (Φf) were determined by using a series of dilute solutions with absorbance in the range of 0.02–0.06 at a particular excitation wavelength. Cresyl violet perchlorate (0.55 in methanol) and methylene blue (0.03 in methanol) were used as external standards for BODIPYs 2, 6a, 6b, 4 and 3, 7, 8, respectively. The relative fluorescence quantum yields (Φf) were determined using the following equation (1),4c

| (1) |

where Φ represent the fluorescence quantum yields; ƞ represent the refractive indexes of solvents; Grad represent the gradient from the plot of integrated fluorescence intensity vs absorbance at λex; Subscripts X and R represent the tested sample and standard sample respectively.

4. DFT Calculations

The DFT calculations were carried out using the Gaussian 09 software package. The ground state geometries of the BODIPYs were optimized by the DFT method with the B3LYP functional and 6-31G(d) basis sets.29

5. Cyclic voltammetry

Cyclic voltammetry was carried out using a potentiostat coupled to an Universal Programmer. Current-voltage curves were recorded on an X-Y recorder. A homemade three-electrode cell was used for cyclic voltammetric measurements and consisted of a glassy carbon working electrode, a platinum counter electrode and a homemade saturated calomel reference electrode (SCE). The SCE was separated from the bulk of the solution by a fritted bridge of low porosity, which contained the solvent/supporting electrolyte mixture. Benzonitrile (PhCN, reagentPlus, 99%) for electrochemistry was freshly distilled over P2O5 before use.

6. Cell studies

The cell studies were conducted by adapting reported procedures.28b All cell culture media and reagents were used as received. The human HEp2 cells were maintained in a 50:50 mixture of DMEM:AMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin antibiotic. The cells were sub-cultured twice weekly to maintain sub-confluent stocks.

6.1. Dark Cytotoxicity

The HEp2 cells were plated at 7500 cells per well in a 96-well plate and allowed to grow for 48 h. Stock solutions of the BODIPYs (32 mM) were prepared in 100% DMSO and diluted into final working concentrations (0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100 μM and 200 μM). The cells were exposed to the working solutions of compounds up to 200 μM and incubated overnight (37°C, 95% humidity, 5% CO2). The working solution was removed, and the cells were washed with 1X PBS. The medium containing 20% CellTiter Blue was added and incubated for 4 h. The viability of cells is measured by reading the fluorescence of the medium at 570/615 nm using a micro-plate reader. In this assay, the indicator dye resazurin is reduced to fluorescent resorufin in viable cells, while non-viable cells are not able to reduce resazurin nor to generate a fluorescent signal. The fluorescence signal of viable (untreated) cells was normalized to 100% and non-viable (treated with 0.2% saponin) cells was normalized to 0%.

6.2. Phototoxicity

The human HEp2 cells were prepared as described above and incubated with compound concentrations of 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.125, and 0 μM for 24 h. The loading solution was removed and the cells were washed with 1 × PBS, and then refilled with fresh medium. The cells were exposed to a 600 W halogen lamp light source filtered with a water filter (transmits radiation 250 – 950 nm) and a beam turning mirror with 200 nm to 30 μm spectral range, for 20 min. The total light dose provided was approximately 1.5 J/cm2. After light exposure, the cells were stored in the incubator for 24 h and assayed for cell viability as described above.

6.3. Time-Dependent Cellular Uptake

Human HEp2 cells were prepared as described above. The cells were exposed to 10 μM of each compound solution for 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h. The loading medium was removed at the end of each incubation period and the cells were washed with 1X PBS, and solubilized by adding 0.25% Triton X-100 in 1X PBS. Each compound solution was diluted to 10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625 and 0.3125 μM concentrations using 0.25% Triton X-100 in 1X PBS for standard curve. A cell standard curve was prepared using 104, 2 × 104, 4× 104, 6 × 104, 8 × 104, and 105 cells per well. The cell number was quantified using a CyQuant Cell Proliferation Assay. The compound concentration in cells at each time period was determined using a micro-plate reader at 485/590 nm. Cellular uptake is expressed in terms of compound concentration (nM) per cell.

6.4. Microscopy

Human HEp2 cells were cultured in a 6-well plate and allowed to grow in the incubator (37°C, 95% humidity, 5% CO2) for 24 h. The cells were exposed to10 μM of each BODIPY in medium and incubated for 6 h (37°C, 95% humidity, 5% CO2), followed by the addition of organelle tracers (50 nM LysoSensor Green, 250 nM MitoTracker Green, 100 nM ER Tracker Blue/White and 50 nM BODIPY FL C5 Ceramide) and incubated for 30 min. The cells were washed with PBS three times before imaging. The images were obtained by an upright microscopy with a water immersion objective and DAPI, GFP, and Texas Red filter cubes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01 CA179902), the NSF (CHE 1362641) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (K. M. K., Grant E-680).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

1H, 13C and 11B NMR spectra for all the push-pull BODIPYs, crystal structures with dihedral angles, absorbance and emission spectra, cyclic voltammetry data, DFT calculated frontier orbitals and energy, concentration-dependent dark and phototoxicity, microscopy images. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

S.X. and N.Z contributed equally to this work

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Li J, Liu D, Hong Z, Tong S, Wang P, Ma C, Lengyel O, Lee CS, Kwong HL, Lee S. Chem Mater. 2003;15:1486–1490. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Pawlicki M, Collins HA, Denning RG, Anderson HL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:3244–3266. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Reinhardt BA, Brott LL, Clarson SJ, Dillard AG, Bhatt JC, Kannan R, Yuan L, He GS, Prasad PN. Chem Mater. 1998;10:1863–1874. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Ren X, Jiang S, Cha M, Zhou G, Wang ZS. Chem Mater. 2012;24:3493–3499. [Google Scholar]; (b) Higashino T, Imahori H. Dalton Trans. 2015;44:448–463. doi: 10.1039/c4dt02756f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hagfeldt A, Boschloo G, Sun L, Kloo L, Pettersson H. Chem Rev. 2010;110:6595–6663. doi: 10.1021/cr900356p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Trukhina O, Rudolf M, Bottari G, Akasaka T, Echegoyen L, Torres T, Guldi DM. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:12914–12922. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chou HH, Reddy KSK, Wu HP, Guo BC, Lee HW, Diau EWG, Hsu CP, Yeh CY. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:3418–3427. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b11554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jinadasa RGW, Fang Y, Kumar S, Osinski AJ, Jiang X, Ziegler CJ, Kadish KM, Wang H. J Org Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Loudet A, Burgess K. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4891–4932. doi: 10.1021/cr078381n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Boens N, Leen V, Dehaen W. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:1130–1172. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15132k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bessette A, Hanan GS. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:3342–3405. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60411j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Kaur N, Kaur P, Singh K. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2016;229:499–505. [Google Scholar]; (b) Flores-Rizo JO, Esnal I, Osorio-Martínez CA, Gómez-Durán CFA, Bañuelos J, López Arbeloa I, Pannell KH, Metta-Magaña AJ, Peña-Cabrera E. J Org Chem. 2013;78:5867–5877. doi: 10.1021/jo400417h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhao Y, Lv X, Liu Y, Liu J, Zhang Y, Shi H, Guo W. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:11475–11478. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Kolemen S, Cakmak Y, Erten-Ela S, Altay Y, Brendel J, Thelakkat M, Akkaya EU. Org Lett. 2010;12:3812–3815. doi: 10.1021/ol1014762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Erten-Ela S, Yilmaz MD, Icli B, Dede Y, Icli S, Akkaya EU. Org Lett. 2008;10:3299–3302. doi: 10.1021/ol8010612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bonnier C, Machin DD, Abdi O, Koivisto BD. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:3756–3760. doi: 10.1039/c3ob40213d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Wang Y, Chen L, El-Shishtawy RM, Aziz SG, Mullen K. Chem Commun. 2014;50:11540–11542. doi: 10.1039/c4cc03759f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jiao L, Wu Y, Wang S, Hu X, Zhang P, Yu C, Cong K, Meng Q, Hao E, Vicente MGH. J Org Chem. 2014;79:1830–1835. doi: 10.1021/jo402160b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Niu S, Ulrich G, Retailleau P, Ziessel R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:4848–4853. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shi WJ, Lo PC, Singh A, Ledoux-Rak I, Ng DKP. Tetrahedron. 2012;68:8712–8718. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ulrich G, Barsella A, Boeglin A, Niu S, Ziessel R. Chemphyschem. 2014;15:2693–2700. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201402123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Nano A, Ziessel R, Stachelek P, Harriman A. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:13528–13537. doi: 10.1002/chem.201301045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutter A, Retailleau P, Huang WC, Lin HW, Ziessel R. New J Chem. 2014;38:1701–1710. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Didier P, Ulrich G, Mely Y, Ziessel R. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:3639–3642. doi: 10.1039/b911587k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu H, Mack J, Yang Y, Shen Z. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:4778–4823. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00030g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Zhao N, Xuan S, Fronczek FR, Smith KM, Vicente MGH. J Org Chem. 2015;80:8377–8383. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang H, Vicente MGH, Fronczek FR, Smith KM. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:5064–5074. doi: 10.1002/chem.201304310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhao N, Vicente MGH, Fronczek FR, Smith KM. Chem Eur J. 2015;21:6181–6192. doi: 10.1002/chem.201406550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Priestley ES, De Lucca I, Zhou J, Zhou J, Saiah E, Stanton R, Robinson L, Luettgen JM, Wei A, Wen X, Knabb RM, Wong PC, Wexler RR. Biorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:2432–2435. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishiyama T, Ishida K, Miyaura N. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:9813–9816. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Fronczek FR, Vicente MGH, Smith KM. J Org Chem. 2014;79:10342–10352. doi: 10.1021/jo501969z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansch C, Leo A, Taft RW. Chem Rev. 1991;91:165–195. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao N, Xuan S, Byrd B, Fronczek FR, Smith KM, Vicente MGH. Org Biomol Chem. 2016;14:6184–6188. doi: 10.1039/c6ob00935b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reichardt C. Chem Rev. 1994;94:2319–2358. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olmsted J. J Phys Chem. 1979;83:2581–2584. [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Chen Y, Zhao J, Guo H, Xie L. J Org Chem. 2012;77:2192–2206. doi: 10.1021/jo202215x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen Y, Zhao J, Xie L, Guo H, Li Q. RSC adv. 2012;2:3942–3953. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reichardt C, Welton T. Solvents and Solvent Effects in Organic Chemistry. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2010. Solvent Effects on the Absorption Spectra of Organic Compounds; pp. 359–424. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qin W, Baruah M, Van der Auweraer M, De Schryver FC, Boens N. J Phys Chem A. 2005;109:7371–7384. doi: 10.1021/jp052626n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Lin SH. J Chem Phys. 1970;53:3766–3767. [Google Scholar]; (b) Rurack K, Kollmannsberger M, Daub J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:385–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Umezawa K, Matsui A, Nakamura Y, Citterio D, Suzuki K. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:1096–1106. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nepomnyashchii AB, Bard AJ. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:1844–1853. doi: 10.1021/ar200278b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma R, Lakshmi V, Chatterjee T, Ravikanth M. New J Chem. 2016;40:5855–5860. [Google Scholar]

- 28.(a) Uppal T, Hu X, Fronczek FR, Maschek S, Bobadova-Parvanova P, Vicente MGH. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:3893–3905. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xuan S, Zhao N, Zhou Z, Fronczek FR, Vicente MGH. J Med Chem. 2016;59:2109–2117. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gibbs JH, Robins LT, Zhou Z, Bobadova-Parvanova P, Cottam M, McCandless GT, Fronczek FR, Vicente MGH. Biorg Med Chem. 2013;21:5770–5781. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA, Jr, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark MJ, Heyd J, Brothers EN, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell AP, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam NJ, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian 09. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford, CT, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.