Abstract

Objective

While suicide attempt history is considered to robustly predict completed suicide, previous studies have limited generalizability from using convenience samples of specific methods/treatment settings, disregarding previous attempts, or overlooking first-attempt deaths. Eliminating these biases should more accurately estimate suicide prevalence in attempters.

Method

This observational retrospective-prospective cohort study using the Rochester Epidemiology Project identified 1,490 (555 males/935 females) Olmsted County residents making index suicide attempts (first lifetime attempts reaching medical attention) between 01-01-1986 and 12-31-2007. The National Death Index identified suicides between enrollment and 12-31-2010 (follow-up 3-25 years). Medical records were queried for sex, age, method, and follow-up care for index attempt survivors. Coroner records yielded data on index attempt deaths.

Results

During the study period, 81/1490 enrollees (5.4%) died by suicide. Of the 81, 48 (59.3%) perished on index attempt; 27 of the surviving 33 index attempt survivors (81.8%) killed themselves within a year. Males were disproportionately represented: 62/81 (11.2% of men; 76.5% of suicides) vs 19/81 (2.0% of women, 23.5% of suicides). Of dead index attempters, 72.9% used guns, yielding an odds ratio for gunshot death vs all other methods of 140 [95%CI:60,325]. When adjusted for covariates, survivors given follow-up psychiatric appointments had significantly lower likelihood of subsequent suicide (OR=0.212[95%CI:0.089, 0.507]).

Conclusions

At 5.4%, completed suicide prevalence in this community cohort of suicide attempters was almost 59% higher than previously reported. An innovative aspect of this study explains the discrepancy: by including index attempt deaths—approximately 60% of total suicides—suicide prevalence more than doubled. We contend that counting both index and subsequent attempts deaths more accurately reflects prevalence. Our findings support suicide attempt as an even more lethal risk factor for completed suicide than previously thought. Research should focus on identifying risk factors for populations vulnerable to making first attempts and target risk reduction in those groups.

INTRODUCTION

In 2013, 41,149 Americans died by suicide, making suicide the tenth most common cause of death in the United States and a major public health concern (1). A prior history of suicide attempt is considered one of the most robust predictors of eventually completed suicide (1, 2). One widely cited meta-analysis shows that 8.6% of individuals admitted to a psychiatric unit with suicidal ideation or after a suicide attempt will eventually die of suicide (3). However, as with this study, the data describing the risk of completed suicide after an initial attempt have been derived from studies with limited generalizability. Nearly all have focused on cohorts assembled from convenience samples, thus failing to accurately characterize the risk for the general population, let alone the subset with psychiatric illness. Examples of these restrictions of convenience include cohorts comprised solely of patients admitted to the hospital after attempts (4–6), patients who have used a particular method of attempt (e.g., self‐poisoning) (5, 7, 8), or patients initially seen in emergency departments (9–14).

Furthermore, essentially all studies upon which clinicians base their predictions of suicide risk after a suicide attempt contain two fundamental limitations: (1) subjects have not been specifically studied from their first lifetime (index) suicide attempts, but rather from first attempts made within a study period selected for convenience, and (2) first lifetime suicide attempts resulting in the subject’s death (and presentation to the coroner rather than the emergency department) are routinely ignored such that that suicide risk for attempters has been systematically underestimated in the psychiatry literature.

An example of a paper that contains both of these limitations is the widely cited 2002 systematic review of Owens and colleagues. The authors considered 90 studies published in English after 1970 and restricted to “patients recruited to a study after attending a general hospital as a result of an episode of non-fatal self-harm and reported the proportion who repeated self-harm—fatally or not—for any follow-up period of at least a year.” They found a non-fatal one-year re-attempt rate of 15%, and a fatal rate of 0.5% to 2.0%, rising to more than 5% after nine years (15). However, studies were included without specification of whether the presenting suicide attempt was the first, and those who died on first attempts were not included in analyses. Moreover, the systematic review pooled studies without distinction between convenience cohorts, restricted to particular methods, and cohorts inclusive of all methods. The review also did not distinguish between males and females, combining them into a single group in the analyses.

A search of PsychInfo, Ovid, Medline, Embase, and Scopus databases using search terms “attempted suicide,” “suicide,” “self-injurious behavior,” and “self-harm event” identified approximately 500 abstracts for suicide follow-up studies, of which 150 proved to be cohort studies of suicide attempters that included data on subsequent completed suicides. We found 17 papers that specified attempt methods, all but two of which distinguished between male and female deaths (4–14, 16–21). We found only four studies comparable to ours, all four from Scandinavian countries with long-standing national healthcare and with mortality databases that followed samples of patients from specifically defined suicide attempts. The first, restricted to a cohort of Finnish patients psychiatrically hospitalized after index suicide attempts, found that 3.4% (5.3% of males and 2.0% of females) died as a consequence of a subsequent suicide attempt during an average 4.5-year follow-up period (18). The second, a national cohort study from Sweden, was also restricted to the 34,219 individuals admitted to hospital over a six-year period, 3.5% of whom died by suicide during follow-up periods ranging from 3–9 years (17). The third study was limited to a cohort of all Danish patients older than age 15 having a first contact with either outpatient or inpatient psychiatric services over a 36-year period. Of the 176,347 study patients, 10.2% (17,993) had been admitted to hospital after an incident of deliberate self-harm (method unspecified). During a median follow-up of 18 years, 4.0% of the deliberate self-harm individuals had died by suicide (16). A fourth study examined all 1,400 individuals who killed themselves in a single year in Finland and found that 56% of the deaths (62% of males and 39% of females) occurred on an index suicide attempt (18).

We believed that using a community sample to track the mortality of suicidal individuals from their first self-harm attempts coming to medical attention—regardless of whether they were hospitalized or identified as psychiatric patients—would more accurately show the prevalence of completed suicide after a suicide attempt. We further surmised that by including individuals dying on their first suicide attempt—so-called “coroner cases”—we would more accurately be able to calibrate the potential lethality of suicide secondary to suicide attempt.

METHODS

The population-based cohort of suicide attempters was identified from residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota. The majority of medical care in Olmsted County is provided by a small number of health care facilities, including private practitioners, a group practice with an affiliated hospital, and a tertiary-care medical center with two affiliated hospitals that houses the county coroner’s office. All medical records from these facilities are linked together for essentially all Olmsted County residents through the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) records-linkage system (22, 23).

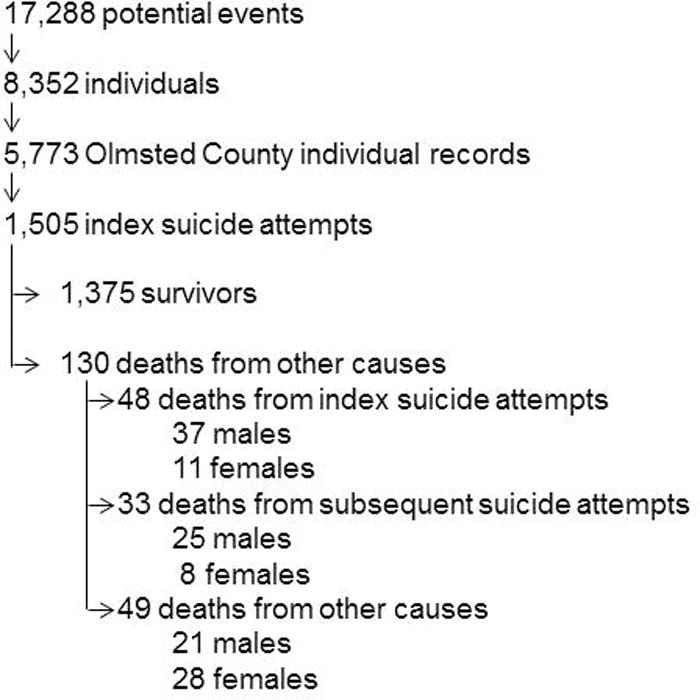

The REP diagnostic index was searched electronically to identify 5,283 Olmsted County residents who received a diagnosis code (Hospital International Classification of Diseases Adapted or International Classification of Disease) between January 1, 1986, and December 31, 2007, corresponding to a suicide attempt. Index date was defined as the earliest date of suicide attempt found during the study period. Medical records for these individuals were reviewed electronically and manually to ascertain past psychiatric history, sex, and attempt method. After excluding those with evidence of prior suicide attempt, a total of 1,490 individuals (555 males, 935 females) had made index suicide attempts during the study period. These individuals had an average age of 27.9 years (SD±14.1) with a median of 23.2 years (IQR=17.2, 35.9) and a range of 10.1 to 91.8 years. A median of 14.8 years of medical record information prior to index attempt (ranged from 0 to 62 years) was available to review to determine index status. All records were abstracted for data about disposition after that initial event including (1) either hospitalization or dismissal from the emergency department, and (2) psychiatric follow-up after discharge from either inpatient or outpatient settings. The National Death Index was queried to identify patients in the cohort who had died before January 1, 2011, and their causes of death. Follow-up ranged from 3 to 25 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Steps taken to identify confirmed index suicide events among Olmsted County residents from 1986–2010.

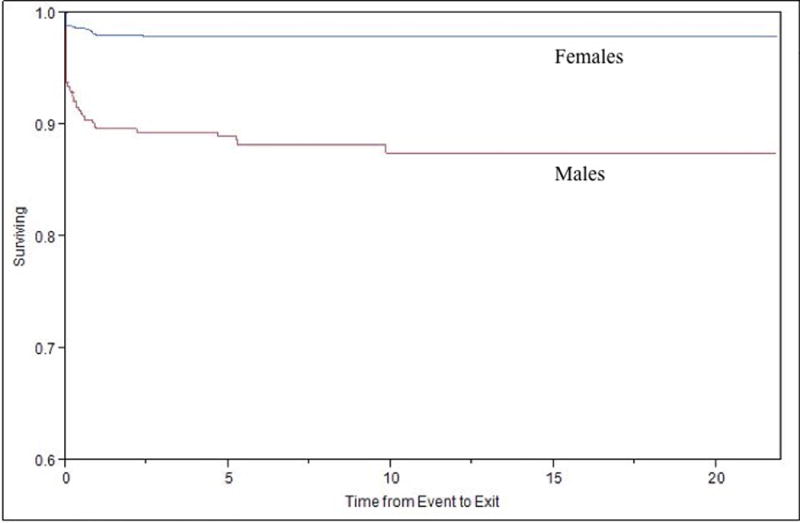

Using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s pairwise tests for age, demographics and clinical characteristics were compared among those who were alive at the end of the study period or died by means other than suicide, those who died after their first suicide attempt, and those who died on subsequent attempt (Table 1). Multivariable logistic regression models were used to test age, gender, clinical factors, and method as predictors of death on initial attempt. Time until completed suicide was plotted on a Kaplan‐Meier curve (Figure 2). All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC).

Table 1.

Demographics by Outcome of Initial Suicide Attempt (N/%)

| Total (N=1490) |

Death on first attempt (N=48) |

Death on subsequent attempt (N=33) |

Alive or death from other cause (N=1409) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 27.9±14.1 | 33.2±15.2 | 41.6±20.7 | 27.4±13.7 | <0.0001 |

| Sex (male) | 555 (37.2) | 37 (77.1) | 25 (75.8) | 493 (35.0) | <0.0001 |

| Past psych history | 895 (60.1) | 22 (45.8) | 17 (51.5) | 869 (61.0) | 0.0694 |

| Past psych diagnosis | 818 (54.9) | 21 (43.8) | 17 (51.5) | 792 (55.6) | 0.2615 |

| Past psych medication | 592 (39.7) | 14 (29.2) | 12 (36.4) | 576 (40.5) | 0.2855 |

| Method of index attempt | |||||

| Hanging/Asphyxiation | 56 (3.8) | 5 (10.4) | 4 (12.1) | 47 (3.3) | |

| Firearms/Explosives | 57 (3.8) | 35 (72.9) | 12 (36.4) | 10 (0.7) | |

| Med Overdose | 858 (57.6) | 5 (10.4) | 7 (21.1) | 846 (60.0) | |

| Poisoning | 58 (3.9) | 3 (6.3) | 4 (12.1) | 51 (3.6) | |

| Cutting/Piercing | 309 (20.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.1) | 307 (21.8) | |

| Other | 152 (10.2) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (12.10 | 148 (10.5) | |

| Type of index attempt management** | |||||

| Med hospitalization | 402 (27.9) | NA | 4 (12.1) | 398 (28.2) | |

| Surgical hospitalization | 21 (1.5) | NA | 1 (3.0) | 20 (1.4) | |

| Psych hospitalization | 689 (47.8) | NA | 6 (18.2) | 683 (48.5) | |

| No hospitalization | 522 (36.2) | NA | 25 (75.8) | 497 (35.3) | |

| Index attempt after-care follow-up | <0.0001 | ||||

| Present | 1002 (69.4) | NA | 8 (24.2) | 992 (70.4) | |

| Absent | 488 (30.6) | NA | 25 (75.8) | 417 (29.6) | |

Mean±SD

More than one type of hospitalization could occur per patient

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve corresponding to survival probability from completed suicide attempt either at initial suicide attempt or after an index suicide attempt, separated by sex.

RESULTS

129 individuals (8.7 % of the sample) died during the study period. 81 (5.4%) of these deaths were suicides, representing 62.8% of deaths. 48 of the suicides occurred on index suicide attempt, and 33 of the 1,442 survivors subsequently died of suicide. The mean (SD) age of those dying on index suicide attempts was 33.2 (15.2), compared with 41.6 (20.7) for those who died on a subsequent attempt. Both groups were significantly older at the end of the study period (N=1,361) than those alive or dead from other causes [N=48, mean (SD): 27.4 (13.7), all-pairwise corrected p<0.05].

The cohort was further divided into five brackets by age. For the sample as a whole, 3.2% died on index suicide attempts, with highest rates in the 25–44 and 65+ age groups. These elevations stemmed from the contributions of male deaths, since peaks for men occurred in these two time periods, with 8.1% of male attempters aged 25–44 and 10.5% of male attempters older than 65 dead on index attempt. The peak for women occurred in the 45–64-year-old group, with 4.0% of attempters dead on index attempt (Table 2).

Table 2.

Rate of Death by Age Cohort

| Index (N/) | Subsequent (N/ of index survivors) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Attempt | Suicide | Survival | Suicide | Other death | Any death |

| 10–14 | 164 | 3 (1.8) | 161 (98.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| 15–24 | 649 | 17 (2.6) | 632 (97.4) | 9 (1.4) | 2 (0.3) | 11 (1.7) |

| 25–44 | 502 | 21 (4.2) | 481 (95.8) | 9 (1.8) | 16 (3.2) | 25 (5.0) |

| 45–64 | 144 | 5 (3.5) | 139 (96.5) | 11 (7.6) | 13 (9.0) | 24 (16.7) |

| 65+ | 31 | 2 (6.5) | 29 (93.5) | 4 (12.9) | 16 (51.6) | 20 (64.5) |

| Overall | 1490 | 48 (3.2) | 1442 (96.8) | 33 (2.2) | 48 (3.22) | 81 (5.4) |

| Males | ||||||

| 10–14 | 36 (6.5) | 1 (2.8) | 35 (97.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) |

| 15–24 | 222 (40.0) | 15 (6.8) | 207 (93.2) | 7 (3.2) | 1 (0.5) | 8 (3.6) |

| 25–44 | 209 (37.7) | 17 (8.1) | 192 (91.9) | 6 (2.9) | 7 (3.3) | 13 (6.2) |

| 45–64 | 69 (12.4) | 2 (2.9) | 67 (97.1) | 8 (11.9) | 6 (8.7) | 14 (20.3) |

| 65+ | 19 (3.4) | 2 (10.5) | 17 (89.5) | 4 (21.1) | 6 (31.6) | 10 (52.6) |

| Overall | 555 | 37 (6.7) | 518 (93.3) | 25 (4.8) | 20 (3.9) | 45 (8.3) |

| Females | ||||||

| 10–14 | 128 (13.7) | 2 (1.6) | 126 (98.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) |

| 15–24 | 427 (45.7) | 2 (0.5) | 425 (99.5) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.7) |

| 25–44 | 293 (31.3) | 4 (1.4) | 289 (98.6) | 3 (1.0) | 9 (3.1) | 12 (4.1) |

| 45–64 | 75 (8.0) | 3 (4.0) | 72 (96.0) | 3 (4.0) | 7 (9.3) | 10 (13.3) |

| 65+ | 12 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (83.3) | 10 (83.3) |

| Overall | 935 | 11 (1.2) | 924 (98.8) | 8 (0.9) | 28 (3.0) | 36 (3.9) |

For those dying from subsequent suicide attempts, the prevalence increased across the life span. For men, 8 of 67—11.9%—of the 45–64-year-old survivors died by suicide as did 4 of 17—23.5%—of males 65 and older. For women, none of the 12 women who were 65 or over who had survived an initial attempt subsequently killed themselves.

The associations of demographics and clinical factors with any death, index death and subsequent completed suicide were first explored using univariate analysis. Older age was marginally associated with higher probability of death (OR=1.6, p=0.091), and significantly associated with index death (OR=1.02, p=0.009). Male sex bestowed a 6.04 odds ratio for death on an index suicide attempt, a risk that was highly significant (p<0.0001). Lethality on an index suicide attempt was significantly associated with method of attempt, as nearly three fourths (72.9%) of those who died on index suicide attempt had shot themselves (p<0.0001). Of index suicide attempt survivors, only 1.5% had shot themselves, whereas nearly 60% had overdosed. To underscore the comparative lethality of the gunshot method versus other methods on index attempt, only 8.9% of hangings, 5.1% of non-medication poisonings, and 0.6% of medication overdoses culminated in death (Table 1).

Importantly, in a multivariate model, neither older age nor sex retained significance after adjustment for gunshot as the method (Table 3). Regardless of sex, those using firearms had 140 times the risk of dying on index suicide attempt than other methods.

Table 3.

Risk of Death on Initial and Subsequent Suicide Attempt

| Event | Predictor | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death first attempt | Age (10 yr units) | 1.158 | 0.907, 1.478 | 0.2387 |

| Male | 1.503 | 0.613, 3.685 | 0.3734 | |

| Shooting method | 140.181 | 60.427, 325.199 | <0.0001 | |

| Subsequent Completed Suicide Attempt (index survivors only) | Age (10 yr units) | 1.556 | 1.277, 1.895 | <0.0001 |

| Male | 4.136 | 1.784, 9.589 | 0.0009 | |

| F/U Psych | 0.212 | 0.089, 0.507 | 0.0005 | |

| Psych hospitalization | 0.326 | 0.124, 0.857 | 0.0230 | |

| Surgical hospitalization | 1.875 | 0.209, 16.821 | 0.5745 | |

| Medical hospitalization | 0.326 | 0.109, 0.976 | 0.0452 |

Similarly, past psychiatric history was univariately associated with increased likelihood of death on initial suicide attempt (OR=1.83, p=0.0396), but not after adjusting for age, gender, and method. Having taken psychotropic medications did not significantly distinguish those who died on an index attempt from those who survived (p=0.123).

For those surviving index suicide attempts but dying in subsequent attempts, older age and male sex were associated with a higher risk of subsequent completed suicide attempt. Having been hospitalized on a medical service or a psychiatric service after an index attempt achieved statistical significance in terms of reducing risk of death, while hospitalization on a surgical service did not prove protective.

A scheduled psychiatry follow-up appointment (surprisingly only 69.4% of index suicide attempt survivors received one), regardless of whether or not survivors had been hospitalized, proved highly protective. Those with appointments were significantly less likely to kill themselves than those without appointments (OR=0.212, Table 3). Only one in four of those dying in a subsequent attempt had scheduled psychiatric follow-up.

Of those dying on subsequent attempts, 20 of 25 males (80.0%) and 7 of 8 females (87.5%) did so within a year of their index attempts, as depicted by a Kaplan-Meier curve corresponding to survival probability from completed suicide, either at initial or subsequent attempt, separated by sex (Figure 2). This K-M curve demonstrates in both males and females (more pronounced in men) the dramatic initial drop attributable to suicide. By three years after index attempt, no female deaths occurred over the next 20 years. For men, all but two of deaths had occurred by year five.

DISCUSSION

Two aspects of this study are innovative. (1) We believe it is the first study to show odds for dying by suicide in a representative community sample of first lifetime suicide attempters that came to medical attention, irrespective of the method they used or the disposition of survivors. (2) This is also the first study to include in longitudinal follow-up those who perished on their first suicide attempt—a large group that has routinely been ignored in calculations of risk. As a result, we argue that our study presents a more accurate picture of the suicide rate for those who attempt suicide at all.

Compared with the three Scandinavian studies that followed hospitalized survivors of index suicide attempts and found that 3.4%, 3.5%, and 4.0% (respectively) died by subsequent suicide (16, 17, 20), our study found a rate of only 2.3% in index attempt survivors. This reduced rate could stem partly from our having included—unlike the Scandinavian studies—patients discharged to home from the emergency department, having been deemed not seriously enough injured or dangerous enough to themselves to require hospitalization. Our findings were in close agreement with the fourth study, the only one we identified that considered the percentage of suicide attempters dying on index attempt (18). In that Finnish study, 56% died on their first lifetime attempts vs 59% in our study. The contribution of these index attempt deaths more than doubles the suicide prevalence in our sample, which at 5.4% is up to 59% higher than the three studies that followed hospitalized survivors of first attempts.

Several of our study findings diverge from broadly held understandings about suicidal behavior. For index attempters, the female-to-male ratio was 1.7, not the widely quoted 4:1 in the literature (2), which presumably could include more than one attempt per subject. We did not gather data on potential subsequent non-lethal attempts that subjects—particularly females—might have perpetuated. We postulate that this narrowing of the traditional ratio in our study may also result from our including only medically documented attempts rather than relying on post hoc survey findings. Similarly, the ratio of male-to-female deaths by suicide was 5.5:1, nearly half again higher than the commonly cited ratio of 4:1 (2). While men in our study were more likely than women to use firearms, females using guns were just as likely as their male counterparts to die on an index suicide attempt. With 6 of 19 male attempters aged 65 or older killing themselves (31.6%), our study replicates the accepted dogma that geriatric males are the demographic group at highest risk for completing suicide (24). Our data also found a peak in male suicides in the 25- to 44-year-old cohort as well as a peak in women in the 45- to 64-year-old age group. No female suicide attempters over age 65 died by suicide. While the rate of completed suicide in our sample rose continuously across the lifespan consistent with recent findings from other Western countries, the sheer volume of index attempts made by those under 25 years of age (813 of 1490, or more than half of our cohort) stands out. Moreover, the youthfulness of the dead—particularly among males—is noteworthy. One in ten males aged 15–24 (9.9%) died by suicide, a proportion not appreciably lower than the 1 in 9 (11.0%) of men killing themselves in the 25–44 age group.

By following patients from their index attempts and including those whose first attempts were lethal, we were able to show that the prognosis from any suicide attempt is even graver than previously believed, particularly for men. Overall, one in 19 attempters—5.4%—killed themselves, including one in nine males, and one in 49 females. One in 15 males and one in 85 females died on their index attempts.

Our data also show how failing to include index attempt deaths leads to underestimation of the odds of completion for those who attempt suicide. 3.2% (48/1,490) of the cohort died on index attempt, whereas only 2.3% (33/1,442) of index attempt survivors went on to kill themselves. This drop in the suicide rate for survivors vs those dead on index attempt held true for both men and women (males 6.7% to 4.8%; women 1.2% to 0.9%). Of importance for risk assessment in index attempt survivors, the vast majority (27/33, 82%) of both men and women who killed themselves on a subsequent attempt did so within the first year (Figure 2).

A limitation of our study is that it does not include individuals who made suicide attempts that did not come to medical attention. These attempters either never informed medical personnel of their attempts, did not injure themselves severely enough to require medical attention, or perished in such a way that their deaths were not classified as suicides. Their absence from the cohort could affect the accuracy of our findings in two ways, either by overestimation of suicide odds in the first two instances, or underestimation in the last. A second limitation is that the study did not identify the number and frequency of subsequent attempts made by survivors of an initial attempt, whether or not they died in a subsequent attempt. A third limitation is the variable follow-up lengths for the subjects: 3 to 26 years. While we found that more than 80% of deaths by suicides in both males and females occurred within a year of the initial attempt, and that all but two subsequent suicides happened within five years, these findings may be overstated since they cannot account for potential late suicides in subjects with shorter enrollment periods. Given the median age for index attempters of 23.2 years and a median of 14.8 years of available medical record information, however, we believe we are likely to have captured the vast majority of index attempts. A fourth limitation is that while we were able to show that having a scheduled follow-up psychiatric appointment after a suicide attempt was associated with a significantly lower rate of subsequent death by suicide, we did not collect data that differentiated those who kept those appointments from those who did not. Clarification of what happens after index suicide attempts could inform which patients are at increased risk for subsequent death by suicide. This could be the subject of future studies using our database.

We believe that this is the first study drawing upon a community rather than convenience sample to ascertain completed suicide prevalence after suicide attempt. It is also the first study to include those dying as a consequence of their first attempt coming to medical attention. As a result of both of these innovations, we contend that our findings represent the most accurate estimation in the literature to date of the odds of suicide as a consequence of suicide attempt.

CONCLUSION

While any history of having attempted suicide is clearly a risk factor for a subsequent attempt, several findings robustly emerge from our study. First, approximately 60% of individuals succumbing to suicide died on their index attempts, with more than 80% of subsequent completed suicides occurring within a year of initial attempt. Second, deaths occurring on index attempts have been ignored in virtually all extant studies of completed suicide rates after attempts, thus dramatically underestimating the deadliness of what is already regarded as a major public health scourge. Third, firearms were implicated in nearly 75% of lethal first attempts by men. Women, although less likely than men to use guns, were equally likely to die when they used that method. Finally, having a follow-up psychiatric appointment scheduled on discharge from either the emergency department or an inpatient service—whether or not it was actually kept—appeared to be strongly protective, significantly reducing the risk of dying on a subsequent attempt.

The implication of these findings is that suicide prevention efforts that commence after index attempt are too late for the nearly two-thirds who die on the first attempt. To be effective, therefore, Future research initiatives should focus on identifying populations at risk of making a first attempt, and suicide prevention programs should redouble efforts to reduce the possibility of individuals—particularly males—of making a first attack on their lives. For index attempt survivors, our data support that the year following that first attempt is a critical period for mustering preventive resources to thwart a lethal repeat attack.

Acknowledgments

Dr Bostwick and Ms Geske had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Ms Geske conducted and is responsible for the data analysis

Grant Support: This study was made possible using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG034676. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no competing interests.

Contributor Information

J. Michael Bostwick, Department of Psychiatry & Psychology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota

Chaitanya Pabbati, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, California

Jennifer R. Geske, Department of Health Sciences Research, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota

Alastair J. McKean, Department of Psychiatry & Psychology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota

References

- 1.Centers of Disease Control and Prevention–National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 10 Leading Causes of Death by Age Group, United States–2013. 2013 [cited 2016 January 17, 2016]; Available from: www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/pdf/leading_causes_of_death_by_age_group_2013-a.pdf.

- 2.Brendel RW, Lagomasino IT, Perlis RH, Stern TA. The Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 1st. Philadelphia: Mosby, Elsevier; 2008. The Suicidal Patient (Chapter 54) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bostwick JM, Pankratz VS. Affective disorders and suicide risk: a reexamination. The American journal of psychiatry. 2000;157(12):1925–32. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tidemalm D, Langstrom N, Lichtenstein P, Runeson B. Risk of suicide after suicide attempt according to coexisting psychiatric disorder: Swedish cohort study with long term follow-up. Bmj. 2008;337:a2205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suominen K, Isometsa E, Ostamo A, Lonnqvist J. Level of suicidal intent predicts overall mortality and suicide after attempted suicide: a 12-year follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Runeson B, Tidemalm D, Dahlin M, Lichtenstein P, Langstrom N. Method of attempted suicide as predictor of subsequent successful suicide: national long term cohort study. Bmj. 2010;341:c3222. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suominen K, Isometsa E, Suokas J, Haukka J, Achte K, Lonnqvist J. Completed suicide after a suicide attempt: a 37-year follow-up study. The American journal of psychiatry. 2004;161(3):562–3. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finkelstein Y, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, Sivilotti ML, Hutson JR, Mamdani MM, Koren G, Juurlink DN. Risk of Suicide Following Deliberate Self-poisoning. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(6):570–5. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suokas J, Suominen K, Isometsa E, Ostamo A, Lonnqvist J. Long-term risk factors for suicide mortality after attempted suicide–findings of a 14-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104(2):117–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ostamo A, Lonnqvist J. Excess mortality of suicide attempters. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36(1):29–35. doi: 10.1007/s001270050287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawton K, Harriss L, Zahl D. Deaths from all causes in a long-term follow-up study of 11,583 deliberate self-harm patients. Psychol Med. 2006;36(3):397–405. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawton K, Fagg J. Suicide, and other causes of death, following attempted suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:359–66. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crandall C, Fullerton-Gleason L, Aguero R, LaValley J. Subsequent suicide mortality among emergency department patients seen for suicidal behavior. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(4):435–42. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christiansen E, Jensen BF. Risk of repetition of suicide attempt, suicide or all deaths after an episode of attempted suicide: a register-based survival analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41(3):257–65. doi: 10.1080/00048670601172749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:193–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB. Absolute risk of suicide after first hospital contact in mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(10):1058–64. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Runeson B, Haglund A, Lichtenstein P, Tidemalm D. Suicide risk after nonfatal self-harm: a national cohort study, 2000–2008. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09453. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lönnqvist J, Ostamo A. Suicide following the first suicide attempt: A five year follow-up using survival analysis. Psychiatria Fennica. 1991;22:171–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkins GR, Hale R, Papanastassiou M, Crawford MJ, Tyrer P. Suicide rate 22 years after parasuicide: cohort study. Bmj. 2002;325(7373):1155. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7373.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isometsa ET, Lonnqvist JK. Suicide attempts preceding completed suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:531–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cullberg J, Wasserman D, Stefansson CG. Who commits suicide after a suicide attempt? An 8 to 10 year follow up in a suburban catchment area. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;77(5):598–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb05173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1996;71(3):266–74. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2012;87(12):1202–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beghi M, Rosenbaum JF, Cerri C, Cornaggia CM. Risk factors for fatal and nonfatal repetition of suicide attempts: a literature review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1725–36. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S40213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]