Summary

Cellular proliferation requires formation of additional cellular membrane material, and the current thinking in the field is that lipids required for this new membrane formation are mostly synthesized de novo. Here we measured the contribution of de novo lipid synthesis in proliferating and contact-inhibited fibroblasts and find that proliferating fibroblasts prefer exogenous palmitate over de novo synthesis. We determined that when exogenous palmitate is provided in culture media at physiological concentrations, de novo synthesis accounts for only ~10% of intracellular palmitate in proliferating fibroblasts, as well as HeLa and H460 lung cancer cells. Blocking fatty acid uptake decreased the rate of fibroblast, HeLa, and H460 cell proliferation, while supplementing media with exogenous palmitate resulted in decreased glucose uptake and rendered cells less sensitive to glycolytic inhibition. Thus, our results suggest that cells scavenging exogenous lipids may be less susceptible to both glycolytic and lipogenic inhibitors.

eTOC blurb

Non-lipid nutrients have been the most studied source of lipids in proliferating cells. Yao et al. show that proliferating fibroblasts, HeLa, and H460 cells prefer to uptake lipids from the extracellular environment directly rather than synthesize them de novo.

Introduction

Synthesis of new lipid membranes is an essential step of cellular proliferation that requires a relatively large supply of intracellular palmitate. This demand for intracellular palmitate can be satisfied in either of two ways. Palmitate can be synthesized de novo from non-lipid nutrients (e.g., glucose and glutamine), or palmitate can be taken up from the extracellular environment directly as a fatty acid or part of a complex lipid. While the latter appears to be more energetically efficient, it is thought to represent only a minor contribution to most proliferating cells.

The type of proliferating cell that has received the most attention with respect to palmitate synthesis and membrane lipids is cancer. In the 1950’s, studies demonstrated with radio labeled tracers that tumor cells synthesize fatty acids from glucose and acetate.(Medes et al., 1953) In 1984, it was concluded that more than 93% of esterified fatty acids in Ehrlich tumor cells are produced by de novo lipid synthesis.(Ookhtens et al., 1984) The importance of de novo lipid synthesis was further supported by later work establishing that clinically aggressive cancers have increased expression and activity of lipogenic enzymes.(Kuhajda, 2000) Additionally, it was demonstrated more recently that inhibition of lipogenic enzymes such as fatty acid synthase and ATP citrate lyase decreases tumor cell proliferation.(Menendez and Lupu, 2007; Mullen and Yet, 2015) On the basis of this evidence, it is often assumed that proliferating cancer cells synthesize the majority of their membrane lipids de novo.

Although it has been asserted that most membrane lipids are also synthesized de novo in proliferating cells that are not malignantly transformed, experimental support for this assumption in non-cancer systems has been comparatively small. Lipogenic enzymes have been found to be required for T cell proliferation, adult neural stem and progenitor cell proliferation, and embryonic development in mice.(Berod et al., 2014; Chirala et al., 2003; Knobloch et al., 2013)

There are also reports linking de novo lipid synthesis to proliferation of human endometrium cells and 3T3 fibroblasts, which are a main focus of the current study.(Hsu et al., 1993; Pizer et al., 1997) Based on these observations, it has been hypothesized that de novo lipid synthesis is critical to cell-cycle progression in non-cancer cells such as fibroblasts.(Kuhajda, 2000) However, quantitative assessments of the contribution of de novo lipid synthesis to intracellular palmitate in proliferating non-cancer cells have been limited.

A potential complication of some of the work referenced above is that it is based on cells cultured in standard media with low levels of fatty acids compared to human serum, which we suspected could force cells toward de novo lipid synthesis. Thus, in this study we aimed to quantify de novo lipid synthesis in proliferating cells cultured in both standard media and media supplemented with palmitate at physiological levels found in healthy human serum (122 ± 48 μM).(Psychogios et al., 2011) We first analyzed glucose, glutamine, and palmitate metabolism in proliferating 3T3 fibroblasts. As a control, we compare these results to contact-inhibited fibroblasts which exhibit a quiescent state. Notably, we find that de novo lipid synthesis only accounts for ~10% of intracellular palmitate in proliferating fibroblasts cultured in media supplemented with palmitate. We then compared these results to those obtained from HeLa and H460 lung cancer cells. Surprisingly we found that contrary to the common assumptions outlined above, only a minor fraction of the intracellular palmitate in these cells was synthesized de novo when standard media was supplemented with palmitate.

Results

Establishing the Quiescent and Proliferative States

Here we compared the same cells (3T3-L1 fibroblasts) in the quiescent and proliferative states by applying untargeted metabolomics. To obtain proliferating cells, fibroblasts were first plated at a low density (1.5 × 104 cells/cm2). After 24 hours, the cell density of these cultures approximately doubled. At this time, the cells were transferred to labeled media, incubated for 5 min, 6 h, or 12 h and then harvested for analysis. Throughout the entire labeling period, the cells remained in the proliferative state (Figure 1A). To achieve the quiescent state, fibroblasts were grown to confluence such that cell-cycle arrest was induced by contact inhibition. Specifically, to obtain quiescent cells, fibroblasts were plated at a high density (6 × 104 cells/cm2). After 24 hours, the cell density was only minimally increased (6.5 × 104 cells/cm2) and approached confluence (Figure 1A). These cells were then transferred to labeled media, incubated for 5 min, 6 h, or 12 h and harvested for comparison to proliferating fibroblasts.

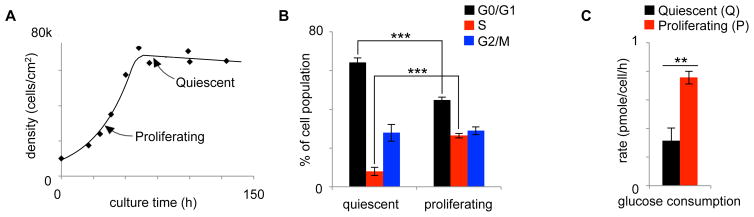

Figure 1.

Establishing the quiescent and proliferative states. A. Plot of 3T3-L1 fibroblast density as a function of culture time. Cells were harvested for comparative analysis at the times indicated by the arrows displayed. B. Cell-cycle analysis at the times indicated by the arrows displayed in Figure 1A. C. Rate of glucose consumption in quiescent and proliferating fibroblasts cultured in standard DMEM with 10% FBS. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=3, **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

To confirm the difference between our quiescent and proliferative cell populations, we performed cell-cycle analysis with propidium iodide. The data showed that the proliferating cultures had a fraction of cells in the S phase that was approximately 3 fold higher than quiescent cultures, indicating that more cells were dividing in these cultures (Figure 1B).(Lemons et al., 2010) To further support the difference in cell populations, we evaluated glucose uptake by analyzing glucose concentration in media over time with LC/MS. Increased glucose consumption is considered to be a hallmark of proliferating cells.(Hsu and Sabatini, 2008) We measured a glucose-uptake rate of 0.31 ± 0.08 picomole/cell/h in quiescent fibroblasts and 0.76 ± 0.04 picomole/cell/h in proliferating fibroblasts cultured in standard media (Figure 1C).

Enrichment of Palmitate from 13C-Glucose Decreases in Proliferating Fibroblasts

We labeled quiescent and proliferating fibroblasts with uniformly enriched 13C glucose (U-13C glucose) for 5 min, 6 h, or 12 h. Multiple time points were used to better assess pathways labeled at different rates. At 5 min, we observed a statistically significant increase in the labeling of all detected glycolytic intermediates in proliferating fibroblasts (Figure 2A). In contrast, at 6 h we observed a statistically significant decrease in the labeling of all detected TCA cycle intermediates in proliferating fibroblasts (Figure 2B). Although here we focus only on total labeling, full isotopologue distributions are included in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Tables 1–4).

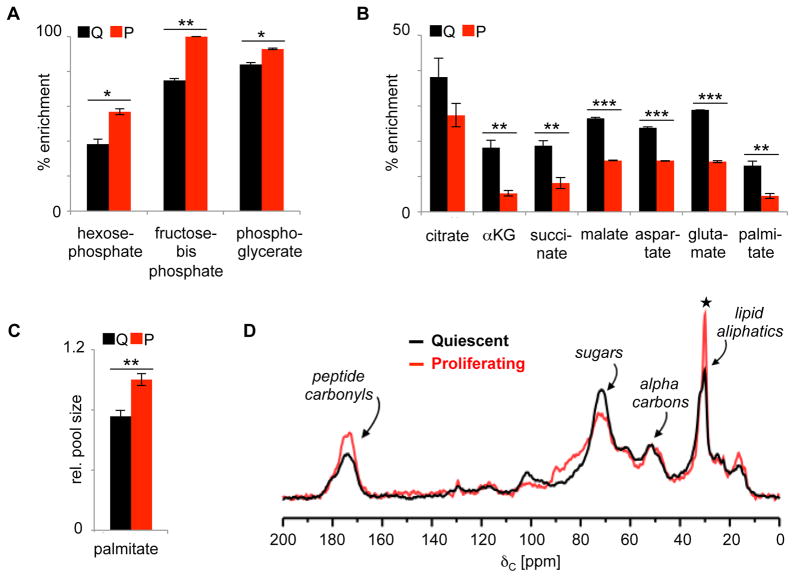

Figure 2.

U-13C glucose labeling of quiescent and proliferating fibroblasts. A. After 5 min of U-13C glucose labeling, glycolytic intermediates have increased isotopic enrichment percentages in proliferating fibroblasts relative to quiescent fibroblasts. B. After 6 h of U-13C glucose labeling, TCA cycle intermediates and palmitate have decreased labeling percentages in proliferating fibroblasts relative to quiescent fibroblasts. C. The pool size of palmitate is ~25% larger in proliferating fibroblasts. Data shown are from the 6 h time point, but data from other time points are consistent. D. 13C CPMAS of intact quiescent fibroblasts (black) and intact proliferating fibroblasts (red) labeled with U-13C glucose for 12 h. Spectra were normalized by scan number and dry sample mass. Natural-abundance contributions (measured experimentally) have been subtracted from the spectra. The narrow peak at 30 ppm corresponds to the aliphatic carbons of lipid chains. The data show that U-13C glucose labels more lipids in proliferating fibroblasts relative to quiescent fibroblasts. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=3, *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001). ★ indicates that the difference in integrated intensities between black and red peaks is larger than the integrated red and black baselines by a p<0.01.

We next focused our attention on palmitate, the precursor of many complex lipids found in cellular membranes. We found that palmitate had an increased concentration in proliferating fibroblasts (Figure 2C). But the labeling of palmitate from U-13C glucose was decreased in proliferating fibroblasts relative to quiescent fibroblasts (Figure 2B). Similarly, the labeling of the acyl chains of complex lipids derived from palmitate was also decreased in proliferating fibroblasts. These decreased labeling percentages suggest either of two possibilities. (i) Less palmitate is being produced from glucose carbon in proliferating fibroblasts. (ii) Alternatively, the amount of palmitate being produced from glucose carbon in proliferating fibroblasts is increased (or does not change), but the labeling of the palmitate pool is diluted by carbon contributions other than glucose.

Proliferating Fibroblasts Synthesize More Lipids from 13C-Glucose than Quiescent Fibroblasts

To distinguish between the two possibilities listed above, we analyzed intact quiescent and proliferating fibroblasts that had been labeled with U-13C glucose for 12 h by solid-state NMR. Data from 13C cross polarization magic angle spinning (CPMAS) experiments were normalized by scan number and dry mass (Figure 2D). These data permit total accounting of glucose label in small molecules as well as macromolecules and indicate how glucose is being differentially metabolized by each cell population.(Chen et al., 2014) The results show that more glucose is metabolized to aliphatic lipid chains (30 ppm) in proliferating fibroblasts.

Cell Proliferation does not rely on Increased Reductive Metabolism of Glutamine

Our solid-state NMR data suggest that the decreased labeling of palmitate in proliferating fibroblasts fed U-13C glucose (as detected by LC/MS) is due to carbon contributions other than glucose diluting the palmitate pool. Consistent with this interpretation, we detected a significant increase in the palmitate pool size of proliferating fibroblasts.

We next aimed to identify the carbon contributions diluting the palmitate pool in proliferating fibroblasts during our glucose-labeling experiments. We first evaluated glutamine. We found that proliferating fibroblasts take up twice as much glutamine from the media as quiescent fibroblasts (Figure 3A). We then labeled quiescent and proliferating fibroblasts with uniformly enriched 13C glutamine (U-13C glutamine) for 6 h and examined the labeling of metabolites by LC/MS. We observed that the labeling of TCA cycle intermediates was greater in proliferating fibroblasts (Figure 3B). This is consistent with glutamine having increased anapleurotic flux in proliferating fibroblasts.

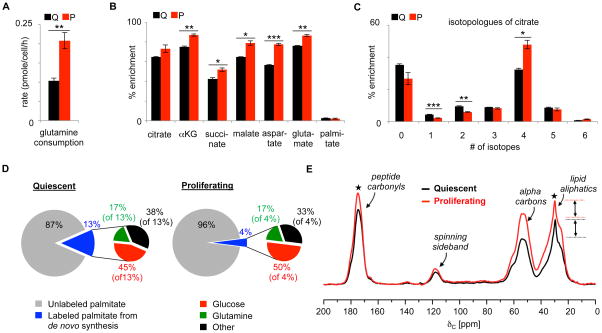

Figure 3.

U-13C glutamine labeling of quiescent and proliferating fibroblasts. A. Proliferating fibroblasts uptake more glutamine than quiescent fibroblasts when cultured in standard DMEM with 10% FBS. B. After 6 h of U-13C glutamine labeling, TCA cycle intermediates have increased labeling percentages in proliferating fibroblasts relative to quiescent fibroblasts. The enrichment of palmitate is not statistically different between proliferating and quiescent fibroblasts. C. Citrate labeling in quiescent and proliferating fibroblasts from U-13C glutamine after 6 h. D. Relative contributions of glucose and glutamine labels to de novo synthesis of palmitate at 6 h in proliferating and quiescent fibroblasts cultured in standard DMEM with 10% FBS. Distributions were determined by using ISA and U-13C glucose and U-13C glutamine data at the 6 h labeling time point. E. 13C CPMAS of intact quiescent fibroblasts (black) and intact proliferating fibroblasts (red) labeled with U-13C glutamine for 12 h. Spectra were normalized by scan number and dry sample mass. Natural-abundance contributions (measured experimentally) have been subtracted from the spectra. The narrow peak at 30 ppm corresponds to the aliphatic carbons of lipid chains. The relative contribution of the 30 ppm peak, determined by experimental deconvolution (see Figure S2), is displayed with arrows. The data show that labeling of lipids by U-13C glutamine is the same between cell populations. In contrast, labeling of the peptide peak at 175 ppm increases in proliferating fibroblasts and indicates that the increased uptake of glutamine in proliferating cultures supports protein synthesis. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=3, *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001). ★ indicates that the difference in integrated intensities between black and red peaks is larger than the integrated red and black baselines by a p<0.01.

Glutamine inserted into the TCA cycle can be metabolized oxidatively in the conventional forward direction, or glutamine can be metabolized reductively in the reverse direction. When U-13C glutamine is metabolized in the forward direction, it ultimately yields a citrate molecule with four 13C labels. The 13C labels are at the one, two, three, and six carbon positions of citrate. Importantly, ATP citrate lyase cleaves carbons at the four and five positions during lipid synthesis. Thus, in the oxidative pathway, glutamine does not contribute any carbon to lipids. This argument assumes that acetyl-CoA is not labeled by glutamine via the malic enzyme, an assumption that is supported in our cells by the ~1% abundance of the M+6 isotopologue of citrate (Figure 3C).

In contrast, the reductive pathway does enable glutamine to contribute carbon to lipid synthesis. In this pathway, glutamine-derived α-ketoglutarate is reductively carboxylated to ultimately produce a citrate molecule with five 13C labels. Here, the four and five position carbons are 13C labeled on citrate. Therefore, in contrast to the oxidative pathway, this citrate can produce acetyl-CoA in which both acetate carbons are 13C enriched for lipid synthesis. We can detect an M+5 isotopologue of citrate in both quiescent and proliferating fibroblasts. In both cell populations, the M+5 isotopologue of citrate is small (~10%, Figure 3C). This suggests that most glutamine is metabolized oxidatively, with minimal change in the reductive pathway between quiescent and proliferating fibroblasts.

To further support that the contribution of glucose carbon to palmitate synthesis increases in proliferating fibroblasts while the contribution of glutamine carbon to palmitate synthesis does not, we performed isotopomer spectral analysis (ISA) by using the mass isotopomer labeling profile of palmitate from our U-13C glucose and U-13C glutamine experiments. (Kelleher and Nickol, 2015; Kharroubi et al., 1992) ISA allowed us to estimate the fractional enrichment of acetyl-CoA from either U-13C glucose or U-13C glutamine. We performed ISA by using the convISA algorithm implemented in MATLAB. (Tredwell and Keun, 2015) After 6 h of labeling in standard Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Media (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), we found that the percentage of glucose-derived acetyl-CoA used for palmitate synthesis increased from 45% in quiescent fibroblasts to 50% in proliferating fibroblasts (Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table 5). In contrast, the percentage of glutamine-derived acetyl-CoA used for palmitate synthesis remained 17% in both quiescent and proliferating fibroblasts (Figure 3D).

Total Accounting by Solid-State NMR Shows No Changes in Glutamine’s Contribution to Lipids

To assess the net contribution of glutamine carbon to lipid synthesis, we performed solid-state NMR on intact quiescent and proliferating fibroblasts that had been labeled with U-13C glutamine for 12h. Data from 13C CPMAS experiments were normalized by scan number and dry mass (Figure 3E). Interpretation of the NMR spectra is complicated by the chemical shift of the glutamine carbons at the 3 and 4 positions, which partially overlap with the aliphatic carbon chemical shift characteristic of lipids. The major glutamine contributions to the NMR spectra resulted from labeled glutamine that had been incorporated into proteins. Thus, we extracted the samples and analyzed the insoluble material (Supplementary Figure S2). The results show that more glutamine is directed into proteins in proliferating relative to quiescent fibroblasts. Additionally, by subtracting the insoluble NMR spectrum from the whole-cell spectrum, we were able to experimentally deconvolve glutamine’s contribution to the aliphatic carbon chemical shift characteristic of lipids. Deconvolution shows that few lipids are labeled from glutamine and that there is minimal change in lipid labeling between quiescent and proliferating cultures (see dashed lines in Figure 3E and solid color in Supplementary Figure S2). Instead, the results demonstrate that the increased glutamine taken up is predominantly routed to protein.

Proliferating Fibroblasts Uptake More Palmitate than Quiescent Fibroblasts

Our LC/MS and solid-state NMR data suggest that carbon sources other than glucose provide increased contributions to the palmitate pool during fibroblast proliferation. We hypothesized that one carbon source contributing to palmitate and complex lipids could be glutamine. However, our results do not support this conclusion. We hypothesized that another potential carbon source for synthesizing complex lipids in proliferating fibroblasts could be exogenous palmitate. When we compared palmitate utilization, we determined that proliferating fibroblasts uptake palmitate at a rate 2–3 fold higher than quiescent fibroblasts. We determined that the rate of palmitate uptake in quiescent fibroblasts is 2.8 ± 0.6 femtomole/cell/h, while the rate of palmitate uptake in proliferating fibroblasts is 8.1 ± 1.2 femtomole/cell/h (Figure 4A). This increase in palmitate uptake in proliferating fibroblasts dilutes the pool of palmitate produced from glucose and is at least partially responsible for the decreased labeling percentages we observe in palmitate from proliferating fibroblasts given U-13C glucose. We also note that palmitate uptake did not increase when fibroblasts were cultured under hypoxic conditions (Supplementary Table 6). Similar to normoxic conditions, under hypoxia, palmitate uptake was ~2 fold greater in proliferating fibroblasts compared to quiescent fibroblasts.

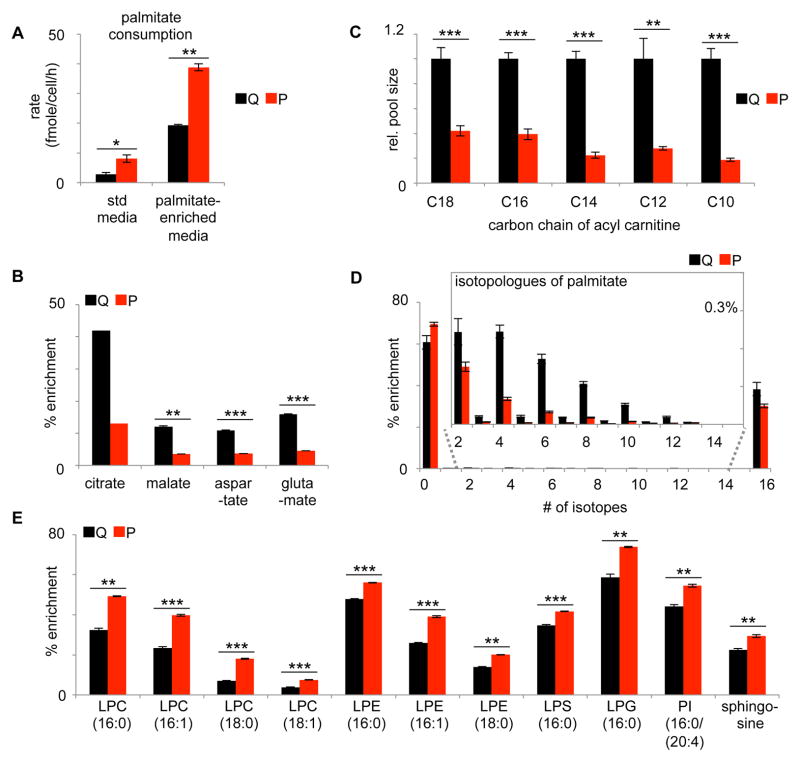

Figure 4.

Proliferating fibroblasts have increased palmitate uptake and deceased palmitate degradation relative to quiescent fibroblasts. A. Proliferating fibroblasts consume more palmitate than quiescent fibroblasts in media having two different palmitate concentrations. B. After 6 h of U-13C palmitate labeling, TCA cycle intermediates have increased labeling percentages in quiescent fibroblasts relative to proliferating fibroblasts. C. The relative pool sizes of acyl carnitines decrease in proliferating fibroblasts. D. Labeling pattern of intracellular palmitate after cells were labeled with U-13C palmitate for 6 h (corrected for natural abundance). The labeling pattern of M2–M14 is enlarged to show futile cycling between palmitate degradation and resynthesis. E. Labeling of complex lipids from U-13C palmitate after 6 h. LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE, lysophosphatidylethanolamine; LPS, lysophosphatidylserine; LPG, lysophosphoglycerol; and PI, phosphatidylinositol. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=3, *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

We next tracked the fate of labeled palmitate by using LC/MS. We fed quiescent and proliferating fibroblasts uniformly 13C labeled palmitate (U-13C palmitate). We grew cells in 100 μM of U-13C palmitate conjugated to albumin. This resulted in a total palmitate concentration in the media of ~110 μM, which approximates the concentration reported in healthy human serum.(Psychogios et al., 2011) Under these conditions, we determined that proliferating fibroblasts similarly have an increase in their rate of palmitate uptake (Figure 4A). Tracking the fate of palmitate labels, we found that palmitate carbon enriches most TCA cycle intermediates at a relatively low level (Figure 4B). The exception is citrate, which has a relatively high enrichment. For all detected TCA cycle intermediates, we observed more labeling in quiescent fibroblasts than proliferating fibroblasts. We attribute these labeling patterns to increased fatty acid oxidation in quiescent fibroblasts relative to proliferating fibroblasts. Although quiescent fibroblasts are synthesizing lipids, they also degrade some of these fatty acids in a wasteful cycle. Our data suggest that futile cycling between fatty acid synthesis and degradation is happening to a lesser extent in proliferating fibroblasts.

Evidence for Increased Degradation of Fatty Acids in Quiescent Fibroblasts

To breakdown fatty acids that cannot pass freely across the inner mitochondrial membrane, the acyl chain must be conjugated to carnitine.(Glatz et al., 2010) In quiescent fibroblasts, we observe a significant increase in the concentrations of C10, C12, C14, C16, and C18 acyl carnitine species ranging from 2 to 5 fold (Figure 4C).

We also examined the labeling pattern of intracellular palmitate in fibroblasts that had been enriched with exogenous U-13C palmitate (Figure 4D). In the absence of fatty acid degradation, we would expect only U-13C palmitate to be detected. Strikingly, we observe a distribution of palmitate isotopologues that suggests labeled palmitate is being broken down and then reassembled (Figure 4D). When re-assembled, the acetyl-CoA units used during synthesis are sometimes derived from U-13C palmitate degradation and sometimes derived from other non-labeled sources. This isotopic distribution is therefore a signature of futile cycling between fatty acid degradation and fatty acid synthesis. The percentage of enriched palmitate that is non-uniformly labeled in quiescent fibroblasts cultured in U-13C palmitate is higher than the percentage of enriched palmitate that is non-uniformly labeled in proliferating fibroblasts cultured in U-13C palmitate. Taken together, these data show that the flux of fatty acid degradation is higher in quiescent fibroblasts compared to proliferating fibroblasts.

Exogenous Palmitate is used to Make Complex Lipids

We have shown that proliferating fibroblasts synthesize more palmitate from glucose carbon compared to quiescent fibroblasts. Additionally, proliferating fibroblasts increase their uptake of exogenous palmitate by 2–3 fold. Our data also show that less palmitate is being catabolized in proliferating fibroblasts. Each of these observations contributes to increasing the intracellular pool of palmitate. Although we observe a small (~25%) increase in the intracellular pool of palmitate in proliferating fibroblasts, these results suggest increased cellular consumption of palmitate.

Proliferating cells must replicate their cellular membranes. Cellular membranes are composed of complex lipids, many of which are derived from palmitate. Thus, we speculated that proliferating fibroblasts use more intracellular palmitate for synthesis of these complex lipids compared to quiescent fibroblasts. Our results were consistent with this hypothesis. In proliferating fibroblasts enriched with U-13C palmitate, we observe increased labeling of all palmitate-derived complex lipids that we examined relative to quiescent fibroblasts. These included phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylinositol, and sphingosine species (Figure 4E).

Estimating the Contribution of Exogenous Palmitate to the Total Intracellular Palmitate Pool

We have shown that palmitate uptake is increased in proliferating fibroblasts. We next sought to determine the contribution of this exogenous palmitate to the total pool of intracellular palmitate in proliferating fibroblasts by using ISA as described above. We cultured proliferating fibroblasts in U-13C glucose for 120 h and used ISA to estimate two parameters: Dglucose and g(120h). Dglucose represents the fractional enrichment of acetyl-CoA from glucose, and g(120h) represents the fractional de novo synthesis of palmitate during 120 h of glucose labeling. As we approached isotopic steady state at 120 h, g(120h) approximates the total contribution of de novo synthesis to the intracellular pool of palmitate.

When we grew fibroblasts in standard DMEM with 10% FBS, we found that a significant amount of intracellular palmitate is fully unlabeled, indicating that it is scavenged from the media. We note that palmitate is a possible contaminant of plastics, columns, and chromatographic lines. Thus, we also applied ISA to palmitoyl carnitine (which does not have a competing background signal) and approximated that 30% of the intracellular palmitate pool results from exogenous lipid. When we performed the same analysis with HeLa and H460 lung cancer cells, we obtained a similar result (Table 1). Notably, the contribution of de novo synthesis to the intracellular palmitate pool decreased even further when we repeated the experiments by culturing cells in media supplemented with 100 μM palmitate. Under these conditions, we estimated that the contribution of exogenous lipid to the pool of intracellular palmitate was ~90% for proliferating fibroblasts (Table 1). Exogenous lipid was also the major contributer to intracellular palmitate in HeLa and H460 cells.

Table 1.

ISA values from labeling experiments approaching isotopic steady state suggest that the majority of intracellular palmitate comes from exogenous sources when palmitate is provided at physiological concentrations.

| Standard Media

|

Palmitate-supplemented Media

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferating1 3T3-L1 | Hela1 | H4601 | Proliferating1 3T3-L1 | Hela1 | H4602 | |

|

|

|

|||||

| Dglucose | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| G | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.82 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.05 |

120 h labeling

48 h labeling

An Inhibitor of Fatty Acid Uptake Decreases the Proliferation Rate of Fibroblasts, HeLa, and H460 Cells

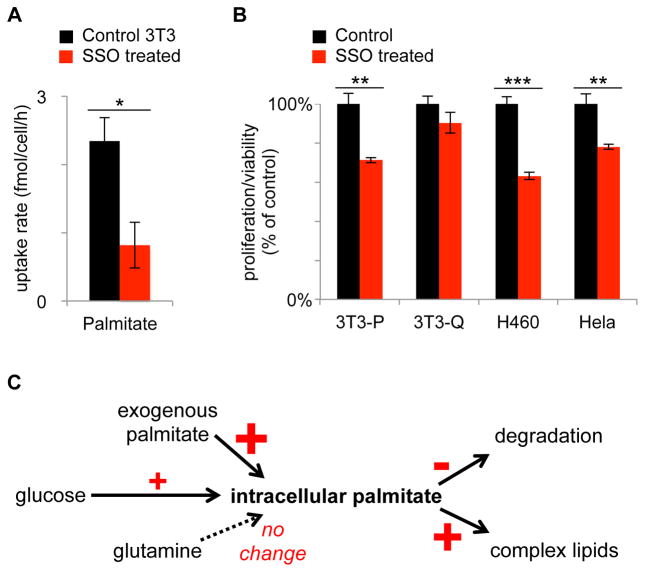

Given the substantial contribution of exogenous lipids to the pool of intracellular palmitate, we next aimed to evaluate the effect of blocking fatty acid uptake. We treated cells with sulfo-N-succinimidyl oleate (SSO), a drug which has been shown to be an inhibitor of fatty acid uptake via multiple mechanisms.(Coort et al., 2002; Harmon et al., 1991; Kuda et al., 2013) First, we demonstrate that treatment of proliferating fibroblasts with 500 μM of SSO for 48 h decreased cellular uptake of palmitate by a factor of ~3 (Figure 5A). We then show that 500 μM SSO decreases the proliferation rate of fibroblasts by 30% (Figure 5B). Using concentrations of SSO greater than 500 μM led to a further decrease in fibroblast proliferation rate (see dose-response results in Supplementary Figure S3). We could partially rescue SSO-treated fibroblasts by supplementing them with additional palmitate. We note, however, that SSO also blocks the uptake of other fatty acids in addition to palmitate. Therefore, we expected that fibroblasts could not be completely rescued by palmitate supplementation alone. In contrast to proliferating fibroblasts, we found that 500 μM SSO did not have a statistically significant effect on the viability of quiescent fibroblasts.

Figure 5.

Alterations in palmitate metabolism in proliferating fibroblasts. A. Treatment of proliferating fibroblasts with SSO decreases palmitate uptake. B. Treatment of proliferating fibroblasts (3T3-P), H460, and HeLa cells with SSO decreases proliferation. Treatment of quiescent fibroblasts (3T3-Q) with SSO has no statistically significant effect. C. Proliferating fibroblasts have increased synthesis of palmitate from glucose carbon, increased palmitate uptake, and decreased palmitate degradation. Synthesis of complex lipids from palmitate is increased. The contribution of glutamine carbon to lipid synthesis has minimal change. Bigger changes in proliferating fibroblasts relative to quiescent fibroblasts are indicated with larger +/− signs. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=3, *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

We also assessed the applicability of these results to proliferating HeLa and H460 lung cancer cells by treating them with 500 μM of SSO. For both HeLa and H460 cells, SSO treatment resulted in a statistically significant decrease in proliferation rate (Figure 5B). These results are consistent with exogenous fatty acids serving as important nutrients for cellular proliferation in fibroblasts, HeLa, and H460 cells.

Potential Clinical Implications of Cancer Cells using Exogenous Palmitate

We have demonstrated that two transformed cell lines (HeLa and H460) obtain most of their intracellular palmitate by scavenging from the extracellular environment when they are cultured at physiological concentrations of palmitate. We have also shown that when these same cells are cultured in standard media containing 10-fold less palmitate, they use glucose to synthesize a much larger fraction of their intracellular palmitate de novo. Thus, we hypothesized that palmitate supplementation decreases the demand for de novo synthesis from glucose and may lead to an attenuated rate of glucose uptake. This could have important clinical consequences because increased glucose uptake by cancer cells is the basis of fluordeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), which is routinely used in the clinic to diagnose and stage cancer patients.(Kelloff et al., 2005)

Indeed, we found that culturing proliferating fibroblasts at physiological levels of palmitate results in a ~3-fold decrease in glucose uptake rate (Supplementary Figure S4A). When cultured in supplemental palmitate, proliferating fibroblasts have a glucose uptake rate that is similar to that of quiescent fibroblasts cultured in media supplemented with palmitate. Even though proliferating fibroblasts cultured in media supplemented with additional palmitate uptake less glucose, the labeling patterns of glucose-enriched metabolites remain consistent with the labeling patterns of glucose-enriched metabolites from proliferating fibroblasts cultured in standard media (Supplementary Figure S5). Similarly, the labeling patterns of metabolites enriched by glutamine in proliferating fibroblasts are consistent with and without supplemental palmitate. Additionally, we measured glucose uptake rates for HeLa and H460 lung cancer cells cultured with and without supplemental palmitate in the media. HeLa and H460 cells also showed a statistically significant decrease in their glucose uptake rate in the presence of supplemental palmitate, although the decrease was smaller than that observed for proliferating fibroblasts (Supplementary Figure S4A).

We hypothesized that lipid scavenging desensitizes cancer cells to glycolytic inhibitors, which have been proposed as attractive anticancer therapies. One glycolytic inhibitor that has been examined as a therapeutic is 2-deoxyglucose (2DG).(Pelicano et al., 2006) We performed an experiment to test if culturing H460 cells at physiological levels of palmitate influenced their sensitivity to 2DG inhibition compared to culturing H460 cells in standard media. We found that the addition of supplemental palmitate to culture media resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the sensitivity of H460 cells to various concentrations of 2DG (Supplementary Figure S4B). These results suggest that lipid scavenging by some cancer cells may influence the efficacy of drugs targeting glycolysis.

Discussion

Proliferating cells require a supply of intracellular palmitate to produce structural lipids for the membranes of daughter cells. Isotopic labeling studies have suggested that majority of intracellular lipids in proliferating cancer cells are produced by de novo synthesis.(Lunt and Vander Heiden, 2011) These results have supported the assumption that most proliferating cells rely primarily on de novo synthesis (over extracellular scavenging) to produce membrane lipids.

A complication of the studies quantifying the contribution of de novo lipid synthesis is that they have mostly been performed with standard cell-culture media containing relatively low levels of lipids or performed under other conditions favoring lipogenesis (such as fat-free diets). Thus, these studies may not reflect the metabolic environment of some tumors in cancer patients. As we show here, the contribution of lipid scavenging is context specific. Additionally, previous studies quantifying de novo lipid synthesis in proliferating cells have mostly focused on cancer systems.

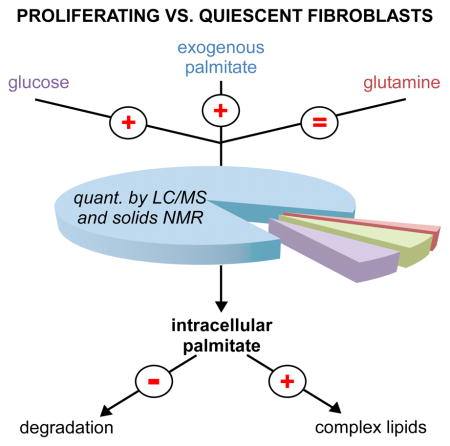

In this study, we provide a quantitative assessment of the contribution of glucose, glutamine, and exogenous palmitate to various classes of lipids in proliferating and quiescent 3T3 fibroblasts (Figure 5C). When fibroblasts are cultured in standard media, the contribution of de novo synthesis to intracellular palmitate is consistent with that which has been reported previously for cancer cells.(Kamphorst et al., 2013; Metallo et al., 2012) However, culturing fibroblasts in standard media revealed two other interesting findings. First, although proliferating fibroblasts take up more glutamine than quiescent fibroblasts, none of the additional glutamine taken up is directed to lipid synthesis. Rather, the additional glutamine taken up is preferentially used to support protein synthesis (Figure 3E and Supplementary Figure S2). Second, our data provide direct evidence that both proliferating and quiescent fibroblasts engage in futile cycling in which synthesized fatty acids are degraded and then subsequently re-synthesized. Notably, this futile cycling process is decreased in proliferating fibroblasts where fatty acids are preferentially used to synthesize complex membrane lipids. On the basis of our experimental observations, we cannot determine if these metabolic alterations are characteristic of proliferating cells other than 3T3 fibroblasts.

We also observed an increased rate of palmitate uptake in proliferating fibroblasts relative to quiescent fibroblasts. These data suggested that scavenging of extracellular palmitate could provide an important contribution to intracellular lipids if the concentration of palmitate was increased to that characteristic of normal serum. Thus, we repeated our comparison of proliferating and quiescent fibroblasts in media supplemented with 100 μM of palmitate. The addition of 100 μM of palmitate resulted in a total palmitate concentration in the media of 110 μM, which approaches the value that has been measured in healthy human serum (122 ± 48 μM).(Psychogios et al., 2011) Strikingly, in the presence of supplemental palmitate, we found that de novo synthesis only accounts for ~10% of the intracellular palmitate in proliferating fibroblasts (Table 1). Instead, extracellular scavenging served as the major source of intracellular palmitate and indicates that proliferating fibroblasts prefer exogenous palmitate over glucose as a carbon source for membrane lipids.

To evaluate the potential role of palmitate scavenging in proliferating cells other than fibroblasts, we performed comparable experiments in HeLa and H460 lung cancer cells. We found that the contribution of de novo synthesis to intracellular palmitate also only accounts for a minor fraction of intracellular palmitate when HeLa and H460 cells are cultured in media supplemented with 100 μM of additional palmitate. It is worth noting that in our experiments we did not supplement the media with other fatty acids known to be present at high concentrations in human serum. Supplementing these additional fatty acids might further increase lipid scavenging.

While some recent reports have demonstrated that exogenous fatty acids are scavenged by cancer cells, the focus of these studies was not quantitative.(Kuemmerle et al., 2011; Louie et al., 2013; Nieman et al., 2011) They do not assess if scavenging represents a small or large contribution to the intracellular palmitate pool. Therefore these studies are not necessarily inconsistent with the assumption that proliferating cancer cells rely primarily on de novo synthesis of palmitate. Here we have quantitated the contribution of lipid scavenging to the intracellular pool of palmitate and determined that it is the major source of intracellular palmitate in fibroblasts, HeLa cells, and H460 cells when they are cultured at physiological levels of palmitate.

The mechanisms of lipid scavenging are complex and poorly understood. Although studies have supported that long-chain fatty acids enter cells by free diffusion, there is also evidence for protein-mediated transport. (Anderson and Stahl, 2013) Both mechanisms have been suggested to be active, but the relative contribution of each is debated and is likely cell/context specific. (Hamilton, 2007; Stahl et al., 2002) Here we treated cells with SSO, a drug that inhibits fatty acid uptake by irreversibly binding to the transport protein CD36. (Coort et al., 2002; Harmon et al., 1991; Kuda et al., 2013) Our results show that SSO decreases palmitate uptake by ~3 fold and therefore suggest that palmitate uptake in the cells we studied is at least partially protein mediated. We note, however, that SSO treatment did not completely inhibit palmitate uptake (Figure 5B). Most likely this is due to other mechanisms of fatty acid uptake that remain active. Nonetheless, our results demonstrate that the proliferation rate of fibroblasts as well as HeLa and H460 cells is decreased by SSO treatment. Complete inhibition of fatty acid uptake by other experimental strategies might lead to even greater decreases in cellular proliferation.

We have found that HeLa and H460 lung cancer cells rely on extracellular palmitate to support their proliferative needs when palmitate is present at concentrations similar to those in healthy human serum. If these results prove to be characteristic of other types of cancer cells, they could have important clinical implications. Interestingly, when HeLa and H460 cells support their lipid needs by scavenging lipids from their environment, these cells also take up less glucose due to decreased lipogenic demands (Supplementary Figure S4A). Increased glucose uptake is considered to be a metabolic hallmark of cancer cells that is routinely exploited in the clinic to diagnose and manage cancer patients by using FDG-PET.(Hsu and Sabatini, 2008; Kelloff et al., 2005) Reduced glucose uptake as a result of lipid availability and subsequent scavenging could therefore contribute to false negative FDG-PET results. Inhibition of glycolysis with drugs like 2DG is also an emerging therapeutic strategy to treat cancer.(Pelicano et al., 2006) Our data show, however, that the ability of H460 cells to scavenge lipids renders them less sensitive to glycolytic inhibition (Supplementary Figure S4B). Finally, while lipogenic enzymes have been proposed to be attractive anti-cancer targets, our results suggest that inhibition of lipogenic enzymes alone may be an insufficient therapeutic approach for some tumors when an extracellular source of lipids is available.

Experimental Procedures

Growth curve and cell cycle analysis

3T3-L1 cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (Life Technology) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technology) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma Aldrich) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. To confirm doubling time and confluent density, cells were seeded at a plating density of 1.0×104 cells/cm2. At selected time points, cells were collected and counted in trypan blue with a hemocytometer. Doubling time was calculated by linear regression against the logarithm of cell density in exponential phase. Cells at indicated times were stained with propidium iodide and cell-cycle analysis was performed by flow cytometry (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Nutrient-uptake analysis

Media was sampled after cells were incubated in fresh media for 6 h. Known concentrations of U-13C internal standards (glucose, glutamine, and palmitate, Cambridge Isotopes) were spiked in media samples before extraction. Extraction was performed as previously reported.(Ivanisevic et al., 2013) Samples were measured by LC/MS analysis (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). The absolute concentrations were determined by calculating the ratio between the fully unlabeled peak from samples and the fully labeled peak from standards for each compound. The consumption rates were normalized by cell numbers.

Glucose, glutamine, and palmitate labeling experiments

Cells were seeded in natural-abundance media at a plating density of 6.0×104 cells/cm2 and 1.5×104 cells/cm2 for quiescent and proliferating conditions, respectively. For labeling experiments, 25 mM U-13C glucose, 4 mM U-13C glutamine, 100 μM U-13C palmitate conjugated to bovine serum albumin (BSA), or their corresponding natural-abundance substrate was added to media supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. For details regarding the preparation of palmitate-BSA, see Supplemental Experimental Procedures. Cells were incubated in labeled media for 5 min (glucose) and 6 h (glucose, glutamine, and palmitate). For all data shown, LC/MS isotopic enrichments were calculated by summing the intensity of isotopologues after natural-abundance correction. To assess the contribution of glucose to intracellular palmitate as cells approached isotopic steady state, cells were labeled with U-13C glucose for 48 h and 120 h, and the media was frequently refreshed to maintain nutrient levels.

Intracellular metabolite analysis

Cells were harvested and extracted as previously described.(Ivanisevic et al., 2013) Samples were analyzed with LC/MS by using an Agilent 6530 Q-TOF, an Agilent 6540 Q-TOF, or a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive Plus (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). The identity of each metabolite was confirmed by comparing retention times and MS/MS data to standard compounds. Pool size measurements were normalized by cellular dry mass. For labeling experiments, the results were corrected for naturally occurring 13C and 12C impurity of the tracers.

Fates of glucose and glutamine by solid-state NMR

Cells were cultured in either natural-abundance media, 20% U-13C glucose (25 mM), or 100% U-13C glutamine (4 mM) media for 12 h. Approximately 2×107 cells were collected for each condition, lyophilized, and then either measured intact or the insoluble macromolecules were extracted and measured as previously reported.(Chen et al., 2014); (Patti et al., 2008) See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for detailed solid-state NMR methods.

SSO treatment and MTT assay

Proliferating 3T3-L1, H460, and HeLa cells were plated in a 96-well plate, with a seeding density of 1 × 104 cells/cm2. Quiescent 3T3-L1 cells were plated with seeding density of 1 × 105 cells/cm2. Cells were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or 500 μM SSO dissolved in DMSO and incubated for 48 h. The proliferation/viability tests were carried out by using an MTT assay (ATCC) and performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Statistical Analysis

Experiments were performed with n=3 samples per group. Data are presented as the means ± SEM. P-values were calculated by performing a Student’s t-test on integrated intensities.

Significance

For a cell to divide, a new cell membrane must first be synthesized. It is often assumed that most of the lipids required for cellular membranes during proliferation are synthesized de novo from non-lipid nutrients such as glucose and glutamine. Here we show that proliferating fibroblasts prefer to uptake palmitate from the media over synthesizing it de novo. When proliferating fibroblasts are cultured at concentrations of palmitate approximating those in healthy human plasma, we determined that ~90% of the intracellular palmitate is taken up from the media. We obtained similar results for HeLa and H460 lung cancer cells. As evidence of the importance of exogenous fatty acids to cellular proliferation, we show that blocking fatty acid uptake reduces the proliferation rate of fibroblasts, HeLa, and H460 cells. These results suggest that lipid transport could be a potential anti-cancer target. Utilization of exogenous palmitate also decreases lipogenic demands and therefore decreases glucose uptake. Interestingly, proliferating fibroblasts cultured at physiological levels of palmitate take up approximately the same amount of glucose as quiescent fibroblasts cultured at physiological levels of palmitate. The effect of culturing Hela and H460 cells in physiological levels of palmitate is smaller, but the trend is consistent. These results are of potential clinical significance because increased glucose uptake is considered to be a metabolic hallmark of cancer cells. Indeed, increased glucose uptake is the basis of FDG-PET imaging, which is widely used for the diagnosis and staging of cancer patients. Additionally, glycolytic inhibitors such as 2DG have been pursued as possible cancer therapeutics. However, we show here that the presence of exogenous palmitate desensitizes H460 cells to 2DG inhibition. One conclusion that we put forward based on the data reposted in this study is that proliferating cells scavenging exogenous lipids may be less sensitive to both glycolytic and lipogenic inhibitors, and we suggest that the exogenous lipid status should be taken into account during diagnosis and treatment of cancer patients.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Exogenous palmitate is preferred over de novo synthesis for 3 cell lines

Proliferating fibroblasts decrease β-oxidation to support complex-lipid synthesis

Glutamine does not contribute more carbon to lipids in proliferating fibroblasts

An inhibitor of fatty acid uptake decreases cellular proliferation in 3 cell lines

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health grants R01 ES022181 (GJP), R21 CA191097-01A1 (GJP), R01 GM116130 (JS), and R01 HL118639-03 (RWG) as well as grants from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (GJP), the Camille & Henry Dreyfus Foundation (GJP), and the Pew Scholars Program in the Biomedical Sciences (GJP).

Footnotes

Author contributions

CY and GJP designed the project. CY, GL, and JS performed the experiments. All authors contributed to data interpretation. CY and GJP wrote the paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson CM, Stahl A. SLC27 fatty acid transport proteins. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:516–528. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berod L, Friedrich C, Nandan A, Freitag J, Hagemann S, Harmrolfs K, Sandouk A, Hesse C, Castro CN, Bahre H, et al. De novo fatty acid synthesis controls the fate between regulatory T and T helper 17 cells. Nat Med. 2014;20:1327–1333. doi: 10.1038/nm.3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YJ, Huang X, Mahieu NG, Cho K, Schaefer J, Patti GJ. Differential Incorporation of Glucose into Biomass during Warburg Metabolism. Biochemistry. 2014;53:4755–4757. doi: 10.1021/bi500763u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirala SS, Chang H, Matzuk M, Abu-Elheiga L, Mao J, Mahon K, Finegold M, Wakil SJ. Fatty acid synthesis is essential in embryonic development: fatty acid synthase null mutants and most of the heterozygotes die in utero. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6358–6363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931394100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coort SL, Willems J, Coumans WA, van der Vusse GJ, Bonen A, Glatz JF, Luiken JJ. Sulfo-N-succinimidyl esters of long chain fatty acids specifically inhibit fatty acid translocase (FAT/CD36)-mediated cellular fatty acid uptake. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;239:213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatz JF, Luiken JJ, Bonen A. Membrane fatty acid transporters as regulators of lipid metabolism: implications for metabolic disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:367–417. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JA. New insights into the roles of proteins and lipids in membrane transport of fatty acids. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2007;77:355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon CM, Luce P, Beth AH, Abumrad NA. Labeling of adipocyte membranes by sulfo-N-succinimidyl derivatives of long-chain fatty acids: inhibition of fatty acid transport. J Membr Biol. 1991;121:261–268. doi: 10.1007/BF01951559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu DK, Donohue PJ, Alberts GF, Winkles JA. Fibroblast growth factor-1 induces phosphofructokinase, fatty acid synthase and Ca(2+)-ATPase mRNA expression in NIH 3T3 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;197:1483–1491. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu PP, Sabatini DM. Cancer cell metabolism: Warburg and beyond. Cell. 2008;134:703–707. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanisevic J, Zhu ZJ, Plate L, Tautenhahn R, Chen S, O;Brien PJ, Johnson CH, Marletta MA, Patti GJ, Siuzdak G. Toward ‘omic scale metabolite profiling: a dual separation-mass spectrometry approach for coverage of lipid and central carbon metabolism. Anal Chem. 2013;85:6876–6884. doi: 10.1021/ac401140h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphorst JJ, Cross JR, Fan J, de Stanchina E, Mathew R, White EP, Thompson CB, Rabinowitz JD. Hypoxic and Ras-transformed cells support growth by scavenging unsaturated fatty acids from lysophospholipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:8882–8887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307237110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher JK, Nickol GB. Isotopomer Spectral Analysis: Utilizing Nonlinear Models in Isotopic Flux Studies. Methods Enzymol. 2015;561:303–330. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2015.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelloff GJ, Hoffman JM, Johnson B, Scher HI, Siegel BA, Cheng EY, Cheson BD, O’Shaughnessy J, Guyton KZ, Mankoff DA, et al. Progress and promise of FDG-PET imaging for cancer patient management and oncologic drug development. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2785–2808. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharroubi AT, Masterson TM, Aldaghlas TA, Kennedy KA, Kelleher JK. Isotopomer spectral analysis of triglyceride fatty acid synthesis in 3T3-L1 cells. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:E667–675. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.263.4.E667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch M, Braun SM, Zurkirchen L, von Schoultz C, Zamboni N, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Kovacs WJ, Karalay O, Suter U, Machado RA, et al. Metabolic control of adult neural stem cell activity by Fasn-dependent lipogenesis. Nature. 2013;493:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuda O, Pietka TA, Demianova Z, Kudova E, Cvacka J, Kopecky J, Abumrad NA. Sulfo-N-succinimidyl oleate (SSO) inhibits fatty acid uptake and signaling for intracellular calcium via binding CD36 lysine 164: SSO also inhibits oxidized low density lipoprotein uptake by macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:15547–15555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.473298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuemmerle NB, Rysman E, Lombardo PS, Flanagan AJ, Lipe BC, Wells WA, Pettus JR, Froehlich HM, Memoli VA, Morganelli PM, et al. Lipoprotein lipase links dietary fat to solid tumor cell proliferation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:427–436. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhajda FP. Fatty-acid synthase and human cancer: new perspectives on its role in tumor biology. Nutrition. 2000;16:202–208. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(99)00266-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemons JM, Feng XJ, Bennett BD, Legesse-Miller A, Johnson EL, Raitman I, Pollina EA, Rabitz HA, Rabinowitz JD, Coller HA. Quiescent fibroblasts exhibit high metabolic activity. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie SM, Roberts LS, Mulvihill MM, Luo K, Nomura DK. Cancer cells incorporate and remodel exogenous palmitate into structural and oncogenic signaling lipids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831:1566–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunt SY, Vander Heiden MG. Aerobic glycolysis: meeting the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:441–464. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medes G, Thomas A, Weinhouse S. Metabolism of neoplastic tissue. IV. A study of lipid synthesis in neoplastic tissue slices in vitro. Cancer Res. 1953;13:27–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:763–777. doi: 10.1038/nrc2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metallo CM, Gameiro PA, Bell EL, Mattaini KR, Yang J, Hiller K, Jewell CM, Johnson ZR, Irvine DJ, Guarente L, et al. Reductive glutamine metabolism by IDH1 mediates lipogenesis under hypoxia. Nature. 2012;481:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature10602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen GE, Yet L. Progress in the development of fatty acid synthase inhibitors as anticancer targets. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25:4363–4369. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.08.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieman KM, Kenny HA, Penicka CV, Ladanyi A, Buell-Gutbrod R, Zillhardt MR, Romero IL, Carey MS, Mills GB, Hotamisligil GS, et al. Adipocytes promote ovarian cancer metastasis and provide energy for rapid tumor growth. Nat Med. 2011;17:1498–1503. doi: 10.1038/nm.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ookhtens M, Kannan R, Lyon I, Baker N. Liver and adipose tissue contributions to newly formed fatty acids in an ascites tumor. Am J Physiol. 1984;247:R146–153. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.247.1.R146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patti GJ, Kim SJ, Schaefer J. Characterization of the peptidoglycan of vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecium. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8378–8385. doi: 10.1021/bi8008032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelicano H, Martin DS, Xu RH, Huang P. Glycolysis inhibition for anticancer treatment. Oncogene. 2006;25:4633–4646. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizer ES, Kurman RJ, Pasternack GR, Kuhajda FP. Expression of fatty acid synthase is closely linked to proliferation and stromal decidualization in cycling endometrium. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1997;16:45–51. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199701000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychogios N, Hau DD, Peng J, Guo AC, Mandal R, Bouatra S, Sinelnikov I, Krishnamurthy R, Eisner R, Gautam B, et al. The human serum metabolome. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl A, Evans JG, Pattel S, Hirsch D, Lodish HF. Insulin causes fatty acid transport protein translocation and enhanced fatty acid uptake in adipocytes. Dev Cell. 2002;2:477–488. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tredwell GD, Keun HC. convISA: A simple, convoluted method for isotopomer spectral analysis of fatty acids and cholesterol. Metab Eng. 2015;32:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.