Abstract

The National Cancer Institute developed the Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating (FLASHE) Study to examine multiple cancer preventive behaviors within parent–adolescent dyads. The purpose of creating FLASHE was to enable the examination of physical activity, diet, and other cancer preventive behaviors and potential correlates among parent–adolescent dyads. FLASHE surveys were developed from a process involving: literature reviews, scientific input from experts in the field, cognitive testing, and usability testing. This cross-sectional, web-based study of parents and their adolescent children (aged 12–17 years) was administered between April and October 2014. The nationwide sample consisted of 1,573 parent–adolescent dyads (1,699 parents and 1,581 adolescents) who returned all FLASHE surveys. FLASHE assessed parent and adolescent reports of several intrapersonal and interpersonal domains (including psychosocial variables, parenting, and the community and home environments). On a subset of example FLASHE items across these domains, responses of parents and adolescents within the same dyads were positively and significantly correlated (r =0.32–0.63). Analyses were run in 2015–2016. FLASHE data present multiple opportunities for studying research questions among individuals or dyads, including the ability to examine similarity between parents and adolescents on many constructs relevant to cancer preventive behaviors. FLASHE data are publicly available for researchers and practitioners to help advance research on cancer preventive health behaviors.

INTRODUCTION

Primary cancer prevention and control, including the promotion of multiple health behaviors (e.g., healthful diet, physical activity, smoking cessation, sun safety) represents an area of scientific emphasis at the National Cancer Institute (NCI).1–4 Evidence supports the association between these healthful behaviors and lower risk for certain types of cancer.5,6 The role of the home, neighborhood environment, and structural-level interventions to promote these health behaviors has been identified as scientific and public health priorities by NIH,7 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,8 and other related programs (e.g., Healthy People 20209 and the First Lady’s Let’s Move! Initiative10). However, there has been less of a focus on understanding the influence of relationships, in particular parent–child relationships, on cancer preventive health behaviors.1 Dyadic study designs can contribute to research on cancer preventive health behaviors, as they allow for analyzing the similarity between dyad members on variables of interest (e.g., health behaviors) and the factors that explain this similarity.11 For example, a dyadic analysis found health-related attitudes to be positively correlated between parents and their young adult children and that young adults’ attitudes influenced their parents’ behaviors.12 Some analyses with friends and couples have also shown obesity prevention behaviors to correlate within dyads and one’s own behaviors and intentions to be influenced by the other dyad member.13–15 Yet, few public use data sources have employed dyadic data to focus on a wide range of cancer preventive behaviors and potential determinants.

To address these priority research areas and gaps, NCI developed the Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating (FLASHE) Survey and public use data set. FLASHE examines psychosocial, generational (parent–adolescent), and environmental correlates of cancer preventive behaviors from an individual and dyadic perspective. FLASHE measures focus on correlates of diet, physical activity, and sedentary behaviors but also assess sleep, sun safety, tanning, and tobacco use. FLASHE data are available for public use (cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/hbrb/flashe.html).

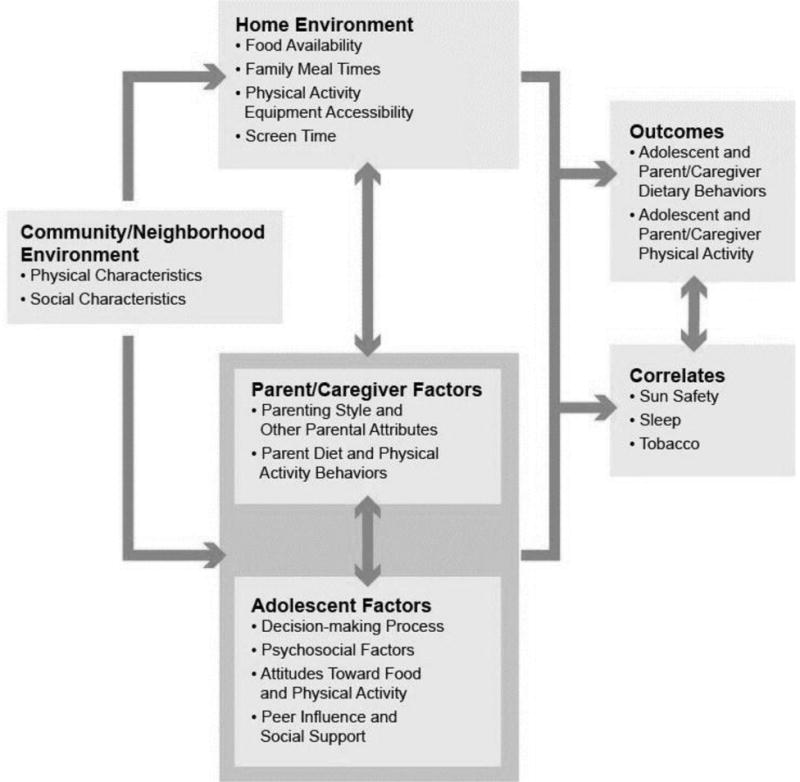

This article describes: (1) the FLASHE conceptual model; (2) steps taken to identify the research priorities and develop the FLASHE survey; and (3) dyadic aspects of the survey design. To demonstrate FLASHE’s dyadic features, correlations between parents’ and adolescents’ responses on example survey items from each level of the FLASHE conceptual model were analyzed (Figure 1). FLASHE data are useful for analyses of both individuals and parent–adolescent dyads. This paper illustrates dyadic research opportunities with the FLASHE data set, given that few public use resources exist that could facilitate this type of inquiry.

Figure 1.

The FLASHE study conceptual framework for multilevel influences on cancer preventive health behaviors.

Notes: The FLASHE conceptual model highlights several levels of influence on adolescent and parent health behaviors (community/neighborhood environment, home environment, parent/caregiver factors, and adolescent factors). Select examples are highlighted within each of these categories, some of which are specific to the core FLASHE behavioral outcomes (diet and physical activity). The behavioral correlates assessed in FLASHE (sun safety, sleep, and tobacco use) are examples of other cancer-related behaviors that may relate to diet and physical activity and are plausibly influenced by the broader aspects of this conceptual model (e.g., community and home environment, adolescent factors, and parent factors).

METHODS

FLASHE Conceptual Framework

The goal of FLASHE is to assess correlates of cancer preventive behaviors among parent–adolescent dyads. The FLASHE conceptual framework was developed, guided by ecologic and behavioral psychosocial frameworks and theories (Figure 1), to explore associations between cancer preventive behaviors. The role of the family16 and home environment are major factors identified in the literature as contributing to obesity risk, including diet and physical activity behaviors. Behavioral theories such as Family Systems Theories,17 the Social Ecological Model,18–19 and Self-Determination Theory20 underscore the nature of the family setting, including the role of parents in shaping their child’s health behaviors, and the home and neighborhood contexts as factors within a complex model of daily life. The Family Systems Theory17 posits that the family environment (e.g., parent relationship) is the most proximal influence on adolescent weight and other health behaviors. Specifically, the family member’s beliefs, parenting practices, and health behaviors can influence adolescents’ behaviors.21 Contextualizing family systems within the Social Ecological Model emphasizes that families and individuals are embedded within community and school contexts, which each have a direct association with behavior.18 Studies have demonstrated that both the built and social environments influence diet22 and physical activity. Health behaviors can also cluster together. For example, screen time, sleep, and diet may be related23,24 among adolescents. This can present an opportunity to intervene on multiple health behaviors, rather than address these behaviors singularly.

The focus of FLASHE is on diet and physical activity behaviors of parent–adolescent dyads. Smoking, sun safety, tanning, sedentary behavior, and sleep were also included as evidence suggests that health behaviors can co-occur.25 Main constructs included intrapersonal or adolescent factors (e.g., barriers, self-efficacy), interpersonal or parent/caregiver factors (e.g., parenting practices and style), the home environment (e.g., food availability, family meals), and the community/neighborhood environment (e.g., neighborhood social cohesion, school vending machine access).

FLASHE Survey Development

Steps taken in the early stages of FLASHE survey development include the following. First, existing literature reviews relevant to the FLASHE conceptual model were reviewed to assess the state of the science. For example, relevant constructs and measures for diet and physical activity behaviors were identified in literature reviews on environmental, family, and psychosocial correlates of diet and physical activity.26–35 Second, NCI consulted with scientific experts experienced in diet, physical activity, obesity, and other cancer preventive behaviors for input on research priorities and the relevance of this survey. Prior to creating a public use data set, these experts provided input through an online survey on the research domains being considered for inclusion in FLASHE. This survey was sent to the e-mail distribution lists of the National Collaborative for Child Obesity Research, the pediatric obesity section membership of The Obesity Society, and special interest groups of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. From 516 responses, the biggest research gap reported overall for diet and physical activity was availability of survey data on the home environment, followed by the community environment. Additional results are available upon request. Insights from literature reviews and consultation with the research community noted above informed the constructs included in the survey.

Development and Testing of Survey Measures

Measures to assess the FLASHE survey constructs were informed from multiple sources. Measures were identified through the scientific literature, and scales were suggested from a team of 19 scientific advisors who had published in areas relevant to the FLASHE survey (e.g., scientists working in childhood obesity prevention, physical activity and diet/nutrition assessment, parenting, and related fields, such as correlates of health behaviors). The FLASHE survey items were reviewed by the scientific advisors for public relevance and consistency with existing validated measures and surveys. New items were developed if a validated measure could not be identified from the literature. Items from existing scales were often modified to meet the goals of FLASHE. It was important that items could be included in an online survey format. Dyadic questions needed to be asked the same way for parents and adolescents when possible. Finally, given the scope of the FLASHE survey constructs and the need to reduce respondent burden, measures needed to be relatively brief.

Cognitive and Usability Testing

After measures were identified, Westat, Inc. conducted cognitive and usability testing of FLASHE to further refine the set of FLASHE measures, specific survey items, and survey format, with input from NCI scientific staff. An aim of cognitive testing was to identify issues that could contribute to response error, and test new questions, questions not used with a population of adolescents or dyads, or questions that needed similar wording in parents and adolescents given the study’s dyadic structure. Two rounds of cognitive testing were conducted for both the parent and adolescent surveys, with a total of 18 parent–adolescent pairs. During the cognitive interviews, respondents completed the FLASHE surveys while receiving questions from interviewers focused on how participants arrived at answers and whether they understood what the question was asking. Following the first round, results of cognitive testing were used to guide modification of the measures and items included in the survey. The revised survey was cognitively tested again. Construct measures and items that were well understood by both parents and adolescents were prioritized for inclusion in the survey, consistent with recommended approaches for facilitating dyadic data analysis.36 Though several edits were made during and after testing, recommendations from cognitive testing generally included: rewording instructions or items, or dropping scales or items, to facilitate comprehension.

After cognitive testing, the survey was formatted to be web based and usability testing was conducted. Nine adolescents completed the FLASHE surveys on a computer in the presence of an interviewer, asking aloud any questions they had while completing it. As needed, the interviewer administered probes to elicit details about survey experiences. Usability testing examined ease of survey navigation, survey item formatting, and overall survey design. Most adolescents were able to navigate through the survey and respond to questions in various formats (e.g., grid questions). Usability testing informed minor refinements to the survey, including refining some button labels and navigational features for ease of saving and clearing answers.

FLASHE Survey Structure

The FLASHE Study recruited participants through the Ipsos Consumer Opinion Panel. Although FLASHE includes a non-probability sample, dyads were recruited from all regions of the U.S. and efforts were taken to select a sample that was similar to the U.S. population. A sample of panel members that was balanced to the U.S. population as much as possible on gender, Census division, household income, household size, and race/ethnicity was screened for eligibility. This screened sample was similar to the U.S. population on age and Census division, but included more female than male participants. Relatively even numbers of adolescents were recruited across ages and gender.37 A total of 5,027 dyads met eligibility criteria (aged ≥18 years and living with an adolescent aged 12–17 at least 50% of the time) and were invited to participate, and 1,945 dyads fully enrolled. FLASHE was divided into four web-based, cross-sectional surveys. Two surveys were administered to each dyad member (adolescent and one parent/caregiver) in 2014: One focused on diet and the other focused on physical activity and other cancer preventive health behaviors. A demographic module, including questions on parenting style, was attached to whichever survey was administered first. Appendix Tables 1 and 2 list all constructs that were included in the final diet- and physical activity–focused surveys as a result of the FLASHE development process and include a footnote listing the constructs in the demographics module. These tables include example citations for the set of survey items assessing each construct. Similar tables are available on the FLASHE webpage,38 and further information on the development of diet and physical activity outcomes can be found in this supplement.39,40 This study received approval from the Office of Management and Budget, the NIH IRB, and the Westat IRB. Details of the study methodology are reported in this issue.37

Dyadic Survey Features and Current Analysis

A central feature of the FLASHE surveys is that they were designed to be dyadic. Each person in the study is linked to one other person in the sample (each adolescent had one parent/caregiver who participated in FLASHE), and parents and adolescents are often asked the same questions to facilitate dyadic analyses11 (the FLASHE website provides the survey items.38) FLASHE therefore facilitates research questions focused on either an individual or the dyad. Dyadic FLASHE data can account for homogeneity (e.g., similarity) and interdependence (e.g., the degree to which dyad members influence each other)11 between parents and adolescents. An example dyadic analysis with FLASHE data is presented in this issue,41 and data users interested in dyadic analysis can also find syntax and tutorials on the FLASHE webpage.38 Appendix Tables 1 and 2 identify which constructs in each FLASHE survey are dyadic. The present analysis presents descriptive information about dyads who completed all four FLASHE surveys. This analysis also highlights the dyadic nature of FLASHE by examining correlations between parents and their adolescents on a subset of FLASHE items from each level of the FLASHE conceptual model.

Statistical Analysis

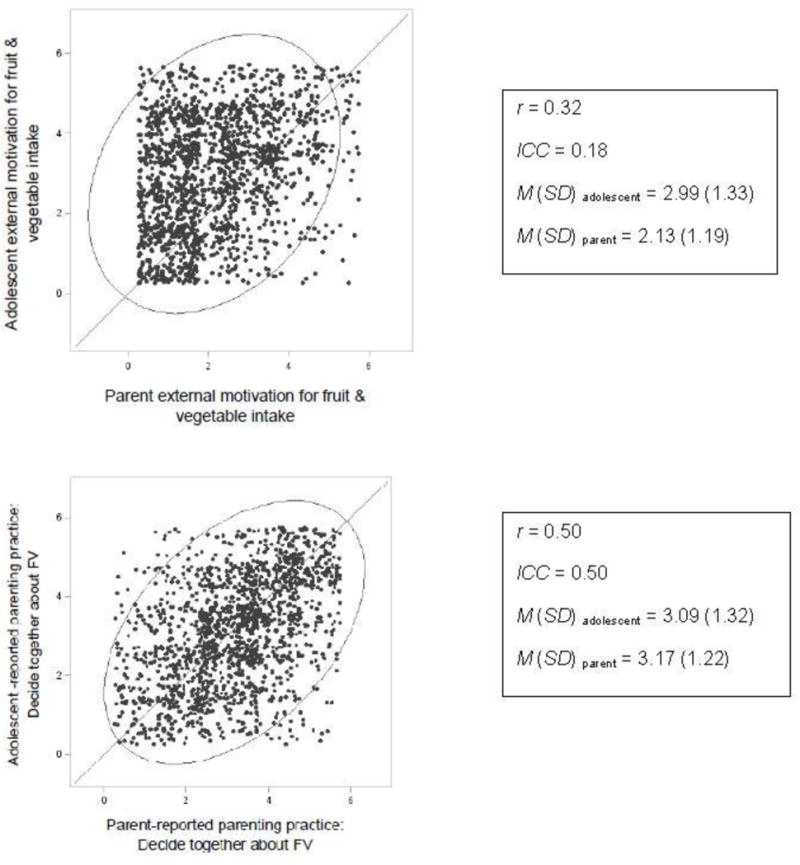

Analyses were run in SAS, version 9.3 in 2015–2016. Frequencies and percentages were run on select demographic factors to describe dyads who completed all four surveys. Unweighted and weighted percentages are shown in Table 1. The FLASHE data sets include analysis weights for parents and adolescents in each survey data set, and the weights were created to reduce sampling bias in individual-level analyses. Dyad-level weights were not computed. More information on data weighting is available in this issue37 and the data users guide on the study webpage. To illustrate the dyadic design of FLASHE, two measures of dyadic non-independence (Pearson and intraclass (ICC) correlations [ICCs]) were computed on example survey items at each level of the FLASHE conceptual model. Variables included: external motivation and barriers (psychosocial), parental support (parent–child factors), availability of fruits and vegetables (home environment), accessibility of stores, and crime (neighborhood environment), and fruit and vegetable intake frequency (outcomes). Table 2 presents information on correlations between responses from dyad members on example items, as measured by the Pearson correlation and ICC.42,43 These measures are often similar or the same in dyadic analysis but can diverge when dyad members respond at different levels (e.g., have different means or SDs).11 In addition, example scatterplots were created to illustrate dyadic association in two cases: (1) a variable that has the same value for the Pearson and ICC; and (2) a variable that a lower value of the ICC compared with the Pearson.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Parents and Adolescents in Dyads Who Completed All FLASHE Surveys (N=1,573 dyads)a

| Demographics | Parent | Adolescent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| n | Unweighted % | Weighted % | n | Unweighted % | Weighted % | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 392 | 24.9 | 42.2 | 779 | 49.5 | 50.7 |

| Female | 1,179 | 75.0 | 57.5 | 788 | 50.1 | 49.0 |

| Not ascertained | 2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 6 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Age | ||||||

| 12–13 years | 528 | 33.6 | 32.2 | |||

| 14–15 years | 537 | 34.1 | 32.8 | |||

| 16–17 years | 506 | 32.2 | 34.7 | |||

| 18–34 years | 177 | 11.3 | 10.0 | |||

| 35–44 years | 684 | 43.5 | 43.0 | |||

| 45–59 years | 666 | 42.3 | 43.6 | |||

| 60+ years | 44 | 2.8 | 3.2 | |||

| Not ascertained | 2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1,097 | 69.7 | 59.6 | 1,005 | 63.9 | 54.4 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 255 | 16.2 | 11.5 | 251 | 16.0 | 13.5 |

| Hispanic | 115 | 7.3 | 16.3 | 154 | 9.8 | 16.0 |

| Other | 90 | 5.7 | 11.7 | 146 | 9.3 | 14.9 |

| Not ascertained | 16 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 17 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Parent education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 21 | 1.3 | 1.2 | |||

| High school degree/GED | 266 | 16.9 | 15.0 | |||

| Some college | 544 | 34.6 | 30.1 | |||

| 4-year college degree or higher | 735 | 46.7 | 53.2 | |||

| Not ascertained | 7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||

| Household income | ||||||

| $0 to $99,999 | 1,225 | 77.9 | 69.7 | |||

| $100,000 or more | 328 | 20.9 | 28.9 | |||

| Not ascertained | 20 | 1.3 | 1.5 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1,132 | 72.0 | 77.8 | |||

| Divorced, widowed, or separated | 189 | 12.0 | 8.9 | |||

| Never married | 146 | 9.3 | 7.7 | |||

| Member of an unmarried couple | 90 | 5.7 | 4.5 | |||

| Not ascertained | 16 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Home ownership | ||||||

| Own | 1,127 | 71.7 | 70.1 | |||

| Not own | 427 | 27.2 | 28.7 | |||

| Not ascertained | 19 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |||

| Number of children in the household | ||||||

| 1 | 629 | 40.0 | 38.7 | |||

| 2 | 562 | 35.7 | 36.9 | |||

| 3 or more | 378 | 24.0 | 24.2 | |||

| Not ascertained | 4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |||

| Parent work status | ||||||

| Employed for wages | 894 | 56.8 | 67.0 | |||

| Self-employed | 126 | 8.0 | 8.9 | |||

| Out of work for more than 1 year | 69 | 4.4 | 3.3 | |||

| Out of work for less than 1 year | 34 | 2.2 | 1.5 | |||

| Not in workforce (homemaker, student, or retired) | 441 | 28.0 | 18.9 | |||

| Not ascertained | 9 | 0.6 | 0.4 | |||

| Adolescent work hours | ||||||

| Work for pay | 218 | 13.9 | 13.7 | |||

| Does not work for pay | 1,351 | 85.9 | 86.1 | |||

| Not ascertained | 4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |||

| Self-rated health status | ||||||

| Excellent | 251 | 16.0 | 16.7 | 662 | 42.1 | 41.7 |

| Very good | 650 | 41.3 | 42.0 | 596 | 37.9 | 38.0 |

| Good | 481 | 30.6 | 31.1 | 226 | 14.4 | 14.7 |

| Fair | 157 | 10.0 | 8.2 | 77 | 4.9 | 4.9 |

| Poor | 24 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 7 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Not ascertained | 10 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 5 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

number of complete dyads (1,573) corresponds to number of dyads in FLASHE who completed all four surveys (parent diet, parent physical activity, adolescent diet, and adolescent physical activity).

FLASHE, Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating Study; GED, general educational development test

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Dyad-Level Pearson Correlations and Intraclass Correlations for Example FLASHE Survey Items

| Construct (Survey) | Item example | n dyadsa | Adolescent M (SD) | Parent M (SD) | Pearson correlation | Intraclass correlationb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial | ||||||

| External motivation for PA (PA) | I would exercise most days of the week because: Others would be upset with me if I didn’t 1 (Strongly Disagree) – 5 (Strongly Agree) |

1,629 | 2.49 (1.25) |

2.17 (1.17) |

0.34 | 0.32 |

| External motivation for fruits and vegetables (Diet) | I would eat fruits and vegetables every day because: Others would be upset with me if I didn’t 1 (Strongly Disagree) – 5 (Strongly Agree) |

1,631 | 2.99 (1.33) |

2.13 (1.19) |

0.32 | 0.18 |

| Barriers – Fruits and vegetables spoil (Diet) | I don’t eat fruits and vegetables as much as I like to because: They often spoil before I get a chance to eat them 1 (Strongly Disagree) – 5 (Strongly Agree) |

1,638 | 2.55 (1.27) |

3.09 (1.33) |

0.38 | 0.32 |

| Family (Parent-Child) | ||||||

| Support (Diet) | My parent(s) [My teenager] and I decide together how many fruits and vegetables I can have [he/she has to eat] 1 (Strongly Disagree) – 5 (Strongly Agree) |

1,626 | 3.09 (1.32) |

3.17 (1.22) |

0.50 | 0.50 |

| Support (PA) | My parent(s) [My teenager] and I decide together how much physical activity I have to do [he/she has to do] 1 (Strongly Disagree) – 5 (Strongly Agree) |

1,623 | 2.75 (1.27) |

2.83 (1.22) |

0.52 | 0.52 |

| Home environment | ||||||

| Availability of FV (Diet) | How often are the following foods and drinks available in your home?: Fruits or vegetables 1 (Never) – 5 (Always) |

1,631 | 4.28 (0.91) |

4.35 (0.84) |

0.58 | 0.58 |

| Neighborhood environment | ||||||

| Accessibility (pa) | Many shops, stores, markets or other places to buy things I need are within a 10–15 minute walk of my home 1 (Strongly Disagree) – 4 (Strongly Agree) |

1,536 | 2.28 (1.12) |

2.21 (1.15) |

0.62 | 0.61 |

| Crime (PA) | The crime rate in my neighborhood makes it unsafe to go on walks at night 1 (Strongly Disagree) – 4 (Strongly Agree) |

1,630 | 1.82 (1.00) |

1.87 (0.99) |

0.63 | 0.63 |

| Behavior | ||||||

| Daily frequency of fruit and vegetable intake (Diet) | Daily fruit and vegetable frequency computed from six items: 100% fruit juice, fruit, green salad, other non-fried vegetables, cooked beans, other (non-fried) potatoes Items response options: 1 (I did not eat [food] during the past 7 days) – 6 (3 or more times per day). Items were recoded and summed to reflect daily fruit/vegetable frequency. |

1,482 | 2.78 (2.04) |

3.03 (1.94) |

0.51 | 0.50 |

Notes: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.001).

“n dyads” = dyads who have complete data on the analysis variable (both parent and adolescent provided non-missing responses). Note that the sample sizes for a particular item may be higher than the sample size in Table 1. The sample sizes in this table only require that parents and adolescents each responded to a particular item in one survey (e.g., diet or PA). The sample size in Table 1 is the number of dyads in which parents and adolescents each responded to both surveys (e.g., diet and PA).

The Pearson correlation and intraclass correlation (ICC) are measures of the degree of association, or similarity, in responding among members of the same dyad. The Pearson and ICC can often be similar in dyadic data,11 as seen in many of the example FLASHE variables in this table that have similar means and SDs. The approach used here for calculating the ICC can be found on the FLASHE webpage37 in the FLASHE Dyadic Analysis User’s Guide and Sample Code (http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/hbrb/docs/FLASHE-Dyadic-Data-Users-Guide.pdf).

FLASHE, Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating Study; FV, fruits and vegetables; PA, physical activity

RESULTS

Table 1 shows descriptive information about the dyads who completed all four surveys (n=1,573 of the 1,945 dyads that enrolled in the study prior to the surveys). Among dyads, 75% of the parents were female, and the majority were aged 35–59 (38.3% of dyads were mother–daughter dyads, 36.3% mother–son, 13.2% father–son, and 11.7% father–daughter). Parents were mostly non-Hispanic white (69.7%), college educated (46.7%), married (72.0%) and worked for wages (56.8%). More than 25% of parents did not own their home. Adolescents were also majority non-Hispanic white (63.9%) and 14% worked for pay. Perceived health was high, with 57.3% of parents and 80% of adolescents reporting their health as very good or excellent. Although Table 1 focuses on dyads in which both members completed their surveys, a total of 1,699 parents and 1,581 adolescents completed each of their individual surveys.

Table 2 presents example FLASHE items, with Pearson correlations and ICCs showing dyadic associations. Sample size varies by item. ICCs and Pearson correlations ranged from low values of 0.18 and 0.32, respectively, for external motivation for fruit and vegetable intake, to a high value of 0.63 for neighborhood crime. For many constructs in Table 2, Pearson correlations and ICCs are very similar, as are means and SDs for parents and adolescents. However, on some constructs, there are differences between the Pearson correlation and ICC, which can be explained by different means or SDs across dyad members. These differences are highlighted in Figure 2. Figure 2A shows a scatterplot of parent and adolescent responses for external motivation for fruit and vegetable intake. For this variable, r =0.32, but the ICC is lower (0.18), with parent and adolescent responses at different mean levels (Madolescents=2.99, SD=1.33; Mparents=2.13, SD=1.19; t=19.57, p<0.001). Figure 2A portrays that adolescent responses tend to be higher than their parent’s responses. By contrast, for parent support for fruit and vegetable intake, adolescents and parents have more similar means (MAdolescents=3.09, SD=1.32; MParents=3.17, SD=1.22; t =1.74, p=0.08). The ICC is also higher for this variable (equivalent to the Pearson), conveying greater within-dyad similarity. This similarity can be seen in Figure 2B, with data points falling closer to the 45-degree line (line of equality).

Figure 2.

(A) scatterplots showing associations between parent and adolescent-reported external motivation for fruit and vegetable intake and (B) parental support for fruit and vegetable intake.

Notes: These scatterplots show the association between parents (x-axis) and adolescents (y-axis) in external motivation for fruit and vegetable intake (A) and parental support for fruit and vegetable intake (B). The ellipse represents 95% of the data points. A greater alignment of the data points near the 45-degree line (line of equality) corresponds to a higher intraclass correlation (within-dyad similarity). There is a greater degree of within-dyad similarity in B (the scatterplot for parent support) as compared to A (the scatterplot for external motivation). In B, more datapoints are close to the line of equality. In A, more data points appear in the upper left area of the scatterplot than in the bottom right area of the scatterplot, showing a greater proportion of dyads in which the adolescent responses were higher than parent responses.

DISCUSSION

The FLASHE Study offers a unique perspective to health promotion, particularly in the areas of diet and physical activity. In addition to being a rich data resource for evaluating individual-level research questions, FLASHE’s focus on dyads has the potential to fill numerous gaps in the literature. Cancer-preventive health behaviors among parent–adolescent dyads have previously not been assessed among a large national sample. The importance of this is partially illustrated by this descriptive analysis. Consistent with prior dyadic analyses of health behavior constructs,11–15 there are correlations between parents and adolescents on multilevel health behavior correlates and fruit and vegetable intake. Further analysis with FLASHE items can examine dyadic associations in larger models. For many example items, parents and adolescents tended to report similar means and SDs and have similar values of Pearson correlations and ICCs. In the FLASHE data, examining both indicators of dyadic interdependence can provide insights into whether the responses of parents and their adolescent children are related and have similar distributions.11,42,43 Such analyses may illustrate dyadic associations to consider in future studies on health behaviors within families.

Limitations

The FLASHE Study was cross-sectional and assessed self-reported behavioral correlates. However, efforts are underway to develop a set of derived geocoded variables that can provide objective indicators of environmental context. Information on this work will be available in the future. A subsample of adolescents also wore accelerometers to provide an objective measure of their physical activity, as described elsewhere in this issue.37,40,44 Though efforts were made to recruit a balanced sample, the FLASHE adult sample included more female than male participants and tended to be highly educated.37 However, FLASHE recruited nationally and includes dyads from all states except Alaska.37 Another limitation is the need to cut relevant survey items based on space constraints. In addition, this paper highlights a select set of survey items to illustrate the capacity for examining parent–adolescent interdependence using the FLASHE data, and is not a comprehensive illustration of the FLASHE variables. Despite these limitations, strengths include the broad scope of correlates included in FLASHE, the multistep survey development process, and the use of similar survey items for parents and adolescents. Data users can examine bidirectional influences of the dyadic relationship using variables in FLASHE.

CONCLUSIONS

The collaborative and multistep effort to create FLASHE helped to strengthen the scientific content of the study by identifying research gaps not currently captured in publically available data and utilizing and developing items to administer to a parent–adolescent dyad population. The FLASHE survey represents a new public use resource to assess a spectrum of cancer preventive health behaviors from both social-ecological and dyadic perspectives. Data users can now address numerous research questions at the individual and dyadic levels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all of the scientific contributors who volunteered their time to provide survey items and review materials. We thank Dr. Kelley Scanlon for her time assisting in the development of the dietary screener, Kate McSpadden for her work in contributing to the development of the Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating (FLASHE) survey, and Dr. Niall Bolger and Dr. Jean-Philippe Laurenceau for their guidance on dyadic analysis and interpretation, and helpful comments on the drafting of this manuscript. We also would like to acknowledge the guest editors of this theme issue on the FLASHE Study, Dr. Leslie Lytle and Dr. Louise Masse, for their review of these manuscripts and helpful feedback.

The FLASHE Study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) under contract number HHSN261201200039I issued to Westat, Inc. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from NCI, NIH, under contract number HHSN261200800001E (Hennessy). The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the DHHS, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Additional funding was provided through a Cancer Research Training Award (CRTA) from the National Cancer Institute (Dwyer). During the timeframe for this work, Dwyer was a CRTA Fellow, Patrick was an NCI employee, Hennessy was an NCI Contractor, and Yaroch was a consultant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Klein WM, Bloch M, Hesse BW, et al. Behavioral research in cancer prevention and control: a look to the future. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(3):303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.004. https://doi.Org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behavioral Research Program, National Cancer Institute, NIH. Priority Areas. http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/priority-areas/. Updated November 2, 2015. Accessed June 20, 2016.

- 3.Ballard-Barbash R, Siddiqi SM, Berrigan DA, et al. Trends in research on energy balance supported by the National Cancer Institute. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4):416–423. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alfano CM, Bluethmann SM, Tesauro G, et al. NCI funding trends and priorities in physical activity and energy balance research among cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;108(1):djv285. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv285. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):30–67. doi: 10.3322/caac.20140. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makarem N, Lin Y, Bandera EV, Jacques PF, Parekh N. Concordance with World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute of Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) guidelines for cancer prevention and obesity-related cancer risk in the Framingham Offspring cohort (1991–2008) Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26(2):277–286. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0509-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-014-0509-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. DHHS, NIH. Strategic plan for NIH obesity research. (NIH Publication No. 11-5493).A report of the NIH Obesity Research Task Force. http://obesityresearch.nih.gov/about/StrategicPlanforNIH_Obesity_Research_Full-Report_2011.pdf. Published March 2011. Accessed July 15, 2016.

- 8.Foltz JL, Belay B, Dooyema CA, Williams N, Blanck HM. Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration: the cross-site overview and opportunities for interventions addressing obesity community-wide. Child Obes. 2015;11(1):4–10. doi: 10.1089/chi.2014.0159. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2014.0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. DHHS. Healthy People 2020 Topics and Objectives. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives. Accessed July 8, 2016.

- 10.White House, DHHS, USDA, US Department of Education, U.S. Department of the Interior. Let’s Move initiative website. www.letsmove.gov. Accessed May 5, 2016.

- 11.Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic Data Analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baiocchi-Wagner EA, Talley AE. The role of family communication in individual health attitudes and behaviors concerning diet and physical activity. Health Commun. 2013;28(2):193–205. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.674911. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2012.674911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopes VP, Gabbard C, Rodrigues LP. Physical activity in adolescents: examining influence of the best friend dyad. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(6):752–756. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burke TJ, Segrin C. Examining diet- and exercise-related communication in romantic relationships: associations with health behaviors. Health Commun. 2014;29(9):877–887. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2013.811625. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2013.811625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howland M, Farrell AK, Simpson JA, et al. Relational effects on physical activity: a dyadic approach to the Theory of Planned Behavior. Health Psychol. 2016;35(7):733–741. doi: 10.1037/hea0000334. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nichols M, Newman S, Nemeth LS, Magwood G. The influence of parental participation on obesity interventions in African American adolescent females: an integrative review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(3):485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.12.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitchurch GG, Constantine LL. Systems theory. In: Boss PG, Doherty WJ, LaRossa R, Schumm WR, Steinmetz SK, editors. Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods: A Contextual Approach. New York: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 325–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-85764-0_14. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao J, Settles BH. Environmental correlates of children’s physical activity and obesity. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(1):124–133. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.1.13. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.38.L13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD. Healthy nutrition environments: concepts and measures. Am J Health Promot. 2005;19(5):330–333. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.5.330. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-19.5.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “What” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inquiry. 2000;11(4):227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birch LL, Davison KK. Family environmental factors influencing the developing behavioral controls of food intake and childhood overweight. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48(4):893–907. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70347-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-3955(05)70347-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reidpath DD, Burns C, Garrard J, Mahoney M, Townsend M. An ecological study of the relationship between social and environmental determinants of obesity. Health Place. 2002;8(2):141–145. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(01)00028-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1353-8292(0100028-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morley BC, Scully ML, Niven PH, et al. What factors are associated with excess body weight in Australian secondary school students? Med J Aust. 2012;196(3):189–192. doi: 10.5694/mja11.11184. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja11.11184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costigan SA, Barnett L, Plotnikoff RC, Lubans DR. The health indicators associated with screen-based sedentary behavior among adolescent girls: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(4):382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spring B, Moller AC, Coons MJ. Multiple health behaviours: overview and implications. J Public Health. 2012;34(Suppl 1):i3–10. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr111. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdr111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cummins S, Macintyre S. Food environments and obesity – neighbourhood or nation? Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:100–104. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi276. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyi276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD. Healthy nutrition environments: concepts and measures. Am J Health Promot. 2005;19(5):330–333. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.5.330. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-19.5.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKinnon RA, Reedy J, Morrissette MA, Lytle LA, Yaroch AL. Measures of the food environment. A compilation of the literature, 1990–2007. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4S):S124–S133. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferreira I, van der Horst K, Wendel-Vos W, et al. Environmental correlates of physical activity in youth – a review and update. Obes Rev. 2006;8(2):129–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00264.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinard CA, Yaroch AL, Hart MH, et al. Measures of the home environment related to childhood obesity: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(1):97–109. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011002059. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980011002059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearson N, Biddle SJ, Gorely T. Family correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(2):267–283. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002589. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980008002589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guillaumie L, Godin G, Vézina-Im LA. Psychosocial determinants of fruit and vegetable intake in adult population: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaikh AR, Yaroch AL, Nebeling L, Yeh MC, Resnicow K. Psychosocial predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption in adults: a review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(6):535–543. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McClain AD, Chappuis C, Nguyen-Rodriguez ST, Yaroch AL, Spruijt-Metz D. Psychosocial correlates of eating behavior in children and adolescents: a review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:54. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-54. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-6-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van der Horst K, Oenema A, Ferreira I, et al. A systematic review of environmental correlates of obesity-related dietary behaviors in youth. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(2):203–226. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl069. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyl069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook WL, Kenny DA. The actor-partner interdependence model: a model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. Int J Behav Dev. 2005;29(2):101–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250444000405. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oh A, Davis T, Dwyer L, et al. Recruitment, enrollment, and response of parent-adolescent dyads in the FLASHE study. Am J Prev Med. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.028. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences. Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating (FLASHE) study. http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/hbrb/flashe.html. Accessed June 20, 2016.

- 39.Smith TM, Calloway E, Pinard CA, et al. Using 24-hour dietary recall data to estimate daily dietary component intake from the Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating (FLASHE) Study dietary screener. Am J Prev Med. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.015. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saint-Maurice PF, Kim Y, Hibbing P, et al. Calibration, validation, and responsiveness of the Youth Activity Profile: the FLASHE study. Am J Prev Med. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.12.010. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dwyer LA, Bolger N, Laurenceau J-P, et al. Autonomous motivation and fruit/vegetable intake in parent-adolescent dyads. Am J Prev Med. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.011. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonzalez R, Griffin D. Modeling the personality of dyads and groups. J Pers. 2002;70(6):901–924. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.05027. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.05027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson WS. The geometric interpretation of agreement. Am Sociol Rev. 1959;24(3):338–345. https://doi.org/10.2307/2089382. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim Y, Hibbing P, Saint-Maurice PF, et al. Surveillance of youth physical activity and sedentary behavior with wrist accelerometry. Am J Prev Med. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.012. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.