Abstract

Repeated mild traumatic brain injury (rmTBI) has been identified by epidemiology as a high-risk factor for dementia at a later stage in life. Animal models to replicate complex features of human rmTBI and/or to evaluate long-term effects on brain function have not been established. In this study, we used a novel closed-head impact model of engineered rotational acceleration (CHIMERA) to investigate the long-term neuropathological and cognitive functional consequences of rmTBI. Adult C57BL/6 male mice were subjected to CHIMERA for 3 consecutive days 24 h apart. Functional outcomes were assessed by the beam walk and Morris water maze tests. Neuropathology was evaluated by immunostaining of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), amyloid precursor protein (APP), and ionizing calcium-binding adaptor molecule-1 (Iba-1), and by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) or Western blotting of GFAP, Iba-1, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Repeated CHIMERA (rCHIMERA) resulted in motor deficits at 3 days, and in learning and memory impairments that were sustained up to 6 months post injury. GFAP and TNF-α gene expression was increased within a week, whereas astrogliosis and microgliosis were induced starting from day 1 up to 6.5 months after rCHIMERA with upregulated GFAP and Iba-1 protein levels. rCHIMERA also induced APP deposition from day 1 to day 7, but this diminished by 1 month. In conclusion, rCHIMERA produces long-lasting cognitive impairments with astrogliosis and microgliosis in mice, suggesting that rCHIMERA can be a useful animal model to study the long-term complications, as well as the cellular and molecular mechanisms, of human rmTBI.

Keywords: : CHIMERA, learning and memory, neuroinflammation, rmTBI

Introduction

According to a report to Congress by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the United States results in ∼2,200,000 emergency department visits, 280,000 hospitalizations, and 50,000 deaths each year.1 Roughly 42,000,000 people worldwide sustain a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) every year.2 mTBI constitutes >75% of TBI, with various causes such as physical abuse, assaults in sports and recreational activities, bomb-explosion blasts on the battlefield, falls, or motor vehicle collisions. The burden of TBI is tremendous, not only on individuals and their families, but also on society, with the economic costs of mTBI estimated to be $17,000,000,000.3

The majority of mTBI patients completely recover within weeks or months; however, 10–20% of mTBI patients, particularly with repeated mTBI (rmTBI), develop post-concussion syndrome.4,5 A number of studies have defined rmTBI or single severe brain injury as a high risk factor for the development of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, post-traumatic stress disorder, Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases, and various neuropsychiatric problems many years after the injury.1,2,6–9 Although several meta-analysis studies have concluded that mTBI was not associated with long-term persistent neuropsychological and cognitive impairments,10–12 other studies reported that mTBI significantly increased long-term sleep problem and cognitive failures and reduced white matter integrity.13–15 Diverse factors such as genotype, age, gender, and pre-injury condition have been attributed to these controversial results. In addition, the presence of the apolipoprotein E4 allele was shown to be associated with poor long-term outcomes of TBI.16,17 These reports suggest that comprehensive studies that consider all aspects surrounding the long-term consequences of rmTBI are warranted, to establish the distinct temporal frame and relationship between rmTBI and chronic neurodegenerative disorders.

It has been a clinical challenge to treat the long-term complications induced by rmTBI, although decades of basic and pre-clinical research on TBI and many promising therapeutic approaches have been demonstrated in animal models of TBI.18 The animal models to replicate complex features of human rmTBI and to address long-term effects have not been established.19,20 The recently developed closed-head impact model of engineered rotational acceleration (CHIMERA) was shown to be a reliable rodent model to mimic many of the functional and pathological characteristics of TBI in humans.21 In this study, we sought to establish an animal model of rmTBI that can recapitulate the long-term behavior and neuropathological consequences of human rmTBI using CHIMERA.

Methods

Experimental animals

Twelve-week-old C57BL/6 male mice purchased from Charles River were housed in the animal facility of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism) with a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle (6:30 to 6:30 h) with free access to standard food and water for a week before the experiments. All experiments were designed to minimize the number of animals used and were approved by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/NIAAA Animal Care and Use Committee (Animal Study Protocol LMS-HK-13) and conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

rCHIMERA injury model

The mice were randomly divided into two groups, rCHIMERA and sham, before the procedure was begun. The mice were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane for 2 min in oxygen (1 L/min), and mounted supine on a holding platform of CHIMERA apparatus angled ∼32 degrees so that the top of mouse head lay flat over a hole in the head plate. Two lines across the piston hole were used to align the mouse head, to limit the impact on the dorsal cortical region covering a 5 mm area surrounding bregma. The impact kinetic energy and velocity of the piston was controlled by the impactor system, which includes an air tank, pressure regulator, digital pressure gauge, two-way solenoid valve, and trigger button. Input kinetic energy (Ek) was calculated using the formula: Ek = ½ mv2 (v: velocity (m/sec), m: mass of piston). In this study, a 0.6J kinetic energy was delivered to mouse head by a 50g piston. The nose cone delivering isoflurane anesthesia was removed, and isoflurane was discontinued when the impact occurred. The injured mice received three impacts 24 h apart. Sham mice were given all procedures except for the impact. After each impact, mice were monitored for the loss of righting reflex (LRR), which is the time interval from the anesthesia state to the first sign of righting reflex, and continuously observed until full recovery. No skull fracture, hematomas, apnea, or death was observed in any injured mice.

The investigators who performed histological or behavioral tests as well as data analyses in this study were not aware of the study group assignments, which were revealed only after all analyses were completed.

Assessment of behavioral changes

The beam walk test was performed at 1, 3, and 5 days after injury. A 7 mm wide and 50 cm long beam was elevated at an angle of ∼55 degrees. Mice were individually placed on the lower end of the beam, and the time taken to walk uphill to the end of the beam was recorded and averaged for two trials per mouse. The Morris water maze (MWM) test was conducted at 1 and 6 months after rCHIMERA and sham procedures. A 120 cm diameter tank was placed in a room that had objects located along the walls to serve as distinct visual cues. The tank was filled with water (22–24°C) rendered opaque using nontoxic white paint, and a 10 cm2 platform was submerged 0.5 cm under water midway between the center and the edge of the tank. The acquisition trials consisted of four 90 sec trials daily for 4 days. The tank was divided into four virtual quadrants such that the platform was centered in one quadrant and the time taken by the mice to find the submerged platform was recorded. In case the mouse failed to locate the platform after 90 sec it was gently guided to the platform and allowed to remain on the platform for 10 sec. A single 60 sec long probe trial was performed 24 h after the last acquisition trial, to assess spatial memory. The platform was removed for this trial, and the time spent by the mice in the quadrant where the platform had been located was recorded.

Immunohistochemical analysis

A subset of rCHIMERA injured mice was anesthetized with isoflurane and transcardially perfused by 0.1M phosphate buffer (PB) (pH 7.4) and fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M PB solution at different time points after injury. Their brains were carefully removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution overnight, and transferred into 30% sucrose solution until sinking to the bottom of tube at 4°C, then embedded with O.C.T. compound medium (VWR, Tissue-Tek, 4583, PA, USA) and frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C freezer until used. Coronal sections (30 μm) were sliced by Leica Cryostat (Leica Biosystems Inc. IL, USA) and stored in cryoprotectant solution at −20°C. Sections from approximately the same position (−1.68 mm bregma) from each mouse brain were selected for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence staining for all biomarkers. Standard Avidin-Biotin Complex (ABC) method was performed on free-floating sections for IHC staining. Briefly, sections were washed through with 1 × Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.1% Triton-100 (3 × 10 min) before quenching of endogenous peroxidase using 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min at room temperature (RT), then blocking with 5% of goat serum at RT for 1 h and probing with the primary antibodies: Iba-1 (Wako, 019-19741, Richmond, VA), GFAP (Sigma Aldrich, cat# G9269, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and APP antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific: 36-6900) at 4°C overnight. The sections were washed again and incubated with biotin-SP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch labs, INC, Code# 111-065-003, PA, USA) for 1 h at RT. ABC was prepared at least 30 min before applying onto sections for 30 min at RT from VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Kit (Vector laboratories, Inc; cat# PK-6100, CA, USA). After rinsing, sections were incubated in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate solution (Vector laboratories, Inc; cat# SK-4100) until desired stain intensity, then washed and air dried overnight. Before sections were mounted on the slides and covered with Permount media (Fisher Scientific; cat# SP15-100, MA USA), they were dehydrated in 70–100% ethanol and cleared in xylene solutions. The procedure of immunofluorescence staining was similar to IHC staining except that the sections were incubated with Iba-1, GFAP, and APP antibodies at 4°C overnight and Alexa fluor-488-conjugated F (ab’)2 fragment goat ant-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch labs, Inc.: 111-546-003) at RT for 1 h. After washing, sections were mounted on the slides and covered with mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector laboratories, Inc: H-1500). Photomicrographs from IHC staining were digitally scanned with Nanozoomer (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Iwata-City, Japan). Immunofluorescence images were captured by an Olympus 1X81 microscope for Iba-1 and GFAP proteins in the optic tract (OT), corpus callosum (CC), hippocampus (HP), cortex (CX), and APP in CC. The GFAP protein expression in the regions of interest (ROIs) was quantified by measuring the fluorescence intensity per μm2 after subtracting the background intensity, and so was the APP protein in CC. The number of Iba-1 positive cells in the ROI was manually counted and presented per mm2 using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Relative expression of GFAP and Iba-1 by Western blotting

Total proteins were extracted from the CX and HP from both rCHIMERA and sham mouse perfused brains at 1 month after injury. The protein concentration was measured by BCA kit (life technologies; product# 1856136, CA, USA). The same amount of protein from each sample was separated on 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Life technologies: NW04120BOX) under denaturing and reduced conditions, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were probed with the following primary antibodies: GFAP (1:5000, Thermo Scientific: cat# MS-1376-P), Iba-1 (1:1000, Wako, 019-19741), phospho-tau (Ser202) (1: 1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, product# 11834, MA, USA) and GAPDH (1:5000, Cell Signaling Technology, product#: 5174S, MA, USA), and with peroxidase-conjugated F(ab’)2 fragment goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG (H+L) as a secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch lab, Inc., code number: 111-036-003). The proteins were detected by Pierce supersignal west pico chemiluminescent detection substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). All images of immunoblots were taken and quantified using KODAK 1D software (Eastman Kodak, NY, USA).

Measurement of gene levels of GFAP, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and APP by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

rCHIMERA and sham mice were perfused by 0.1M PB and euthanized at 1, 3, and 7 days post-injury. Their CX and HP were dissected and quickly frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C. Total RNA from each brain region was extracted by Trizol Reagent (Life technologies, cat# 15596-026) following the manufacturer's protocol, and 2 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to 20 μL cDNA using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystem, cat# 4368814, CA, USA). Two pairs of primers for each target gene crossing exon junction were picked by Primer3 Plus software and synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Iowa, USA); 10 μL of PCR mixture including 1xSYBR Green Master mixture (QIAGEN: cat# 204143, CA, USA). 0.5 μM of sense primer and reverse primer, and 1 μL of cDNA temple was loaded into each well of 384 well PCR plate (Applied Biosystem: cat# 4309849) and run on an ABI 7900 HT machine. The PCR program was: initial denaturation: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 15 min; then 40 cycles: 95°C for 20 sec, 55°C for 20 sec, and 72°C for 20 sec. As an internal control, 18S ribosomal RNA (18S rRNA) was used. Data were analyzed using the comparative CT method. The interesting gene relative mRNA to housekeeping gene 18S rRNA were calculated as 2-ΔΔCt value. Gene levels in rCHIMERA-injured mice were normalized to the sham group.

The sequences of primers used in this study were

-

1. GFAP: Forward: 5′-GAAACCAACCTGAGGCTGGA-3′

Reverse: 5′-TCTCCTCCTCCAGCGATTCA-3′

-

2. TNF-α: Forward: 5′-ACGTCGTAGCAAACCACCAA-3′

Reverse: 5′-AAGGTACAACCCATCGGCTG-3′

-

3. APP: Forward: 5′-CCGTTGCCTAGTTGGTGAGT-3′

Reverse: 5′-TGTGCCAGTGAAGATGGGTC-3′

-

4. Iba-1: Forward: 5′-GCTTTTGGACTGCTGAAGGC-3′

Reverse: 5′-GTTTGGACGGCAGATCCTCA-3′

-

5. 18S rRNA: Forward: 5′-GCAATTATTCCCCATGAACG-3′

Reverse: 5′-GGCCTCACTAAACCATCCAA-3′

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Beam walk, LRR, and MWM learning data were analyzed using repeated measures two way ANOVA followed by the Sidak's test. All immunostaining and gene data were analyzed with one way ANOVA corrected for multiple comparisons by Tukey's post-hoc test. The data of MWM probe, GFAP, and Iba-1 protein levels were analyzed by t test. All data statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 6.04, GraphPad Siftware Inc). A p value set to <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

rCHIMERA resulted in transient motor deficit and long-term cognitive impairments

We measured the duration of LRR to determine transient unconsciousness as an indicator for severity of injury immediately after each impact. Mice exposed to rCHIMERA took four to five times longer to regain righting reflex than sham mice after the first impact (Fig. 1A) (207 ± 44.4 sec vs. sham 38 ± 2.363 sec; p = 0.00112). The second and third impact produced a similar level of LRR as the first impact (the second impact: 197.091 ± 33.56 sec vs. sham 46.2 ± 7.729 sec, p = 0.01; the third impact: 185.818 ± 23.276 sec vs. sham 37 ± 2.569 sec, p = 0.0065). There was no significant difference in the righting time of CHIMERA-injured mice after repeated impacts when analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA (p = 0.87). The motor function was assessed using the elevated beam walk test on days 1, 3, and 5 after the last impact (Fig.1B). The data were analyzed using repeated measures two way ANOVA with Sidak's test. Overall, the CHIMERA mice took a longer time to cross the elevated beam than the sham mice (p < 0.05). Multiple comparisons showed that on days 1 and 3 post-injury, rCHIMERA-inflicted mice took longer time to cross the beam than sham controls (rCHIMERA vs. sham: 10.273 ± 0.708 sec vs. 7.545 ± 0.327 sec, p = 0.0014 on day 1; 8.591 ± 0.635 sec vs. 6.727 ± 0.227 sec, p = 0.029 on day 3); however, their performance reached the sham level on day 5 (rCHIMERA vs. sham: 5.909 ± 0.241 sec vs. 5.591 ± 0.343 sec, p = 0.456). These results indicated that motor deficits in injured animals were transient.

FIG. 1.

Repeated closed-head impact model of engineered rotational acceleration (rCHIMERA) resulted in transient motor deficit and long-term cognitive impairment. Duration of loss of righting reflex (LRR) monitored immediately following each CHIMERA impact indicates that rCHIMERA-injured mice (n = 11) had prolonged LRR at each impact compared with sham mice (n = 11) (A). Beam walk test conducted on rCHIMERA-injured mice (n = 11) on days 1 and 3 after the last injury shows significantly longer time to cross the beam compared to the sham control (n = 11) (B). Morris water maze test performed at 1 month (sham: n = 17, rCHIMERA: n = 18) (C) and 6 months (sham: n = 8, rCHIMERA: n = 14) (D) post-injury in rCHIMERA-injured mice shows significantly longer time to reach the platform during training and less time in the platform quadrant than the sham control. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

The MWM test was conducted for spatial learning and memory function at 1 and 6 months after the third impact. At both time points, the injured animals took longer to reach the platform during training sessions. Two way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test for acquisition trials shows that the injury had a significant effect on the latency to find the platform across 4 days of training (p < 0.001 at 1 min; p < 0.05 at 6.5 min), with significant differences at indicated time points. rCHIMERA-injured mice took almost twice as long to find the platform on day 3 (44.904 ± 4.687 sec vs. 26.804 ± 3.772 sec; p = 0.018) and day 4 (47.000 ± 6.149 sec vs. 24.294 ± 4.297 sec; p = 0.0011) as the sham group at 1 month post-injury. The probe trial was performed 24 h after the last acquisition trial to assess spatial memory (Fig. 1C). Sham mice spent more time in the platform quadrant than would have occurred by chance, which is 15 sec (20.889 ± 3.220 sec vs: 15 sec, p = 0.01 by one sample t test); however, the time spent in the platform quadrant by the injured mice did not differ from the 15 sec chance value (13.49 ± 2.96 sec vs. 15 sec, p = 0.57 by one sample t test), indicating that the injured mice do not remember the platform location. The curves for the distance covered by the mice to reach the platform had similar trends as those of the time to platform although statistical significance was not reached (Fig. 1C). The average swim speed for the rCHIMERA group was also similar to that of the sham group except for day 4 of the training sessions, when the rCHIMERA group was slower than the sham group (0.092 ± 0.008 m/sec and 0.119 ± 0.007 m/sec, respectively; p < 0.05; repeated measures two way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test). We extended this test to 6 months post-injury to determine if the changes in water maze performance after rCHIMERA persisted. Similarly, the learning and memory function remained impaired in rCHIMERA-injured mice as evidenced by the longer escape latency to the platform on day 3 (Fig. 1D) (rCHIMERA vs. sham: 20.000 ± 2.390 sec vs. 30.889 ± 2.213 sec, p = 0.00497) and less time spent in the platform quadrant than the sham control mice (23.170 ± 2.330 sec vs. 17.210 ± 1.904 sec). The curves for the distance travelled to reach the platform for both the experimental groups were similar to the time to platform curves (Fig. 1D). There were no significant differences in the average swim speed between groups. Collectively, these data demonstrate that rCHIMERA induced long-term spatial learning and memory deficits.

rCHIMERA caused persistent astrogliosis

It has been recognized that the white matter network widely disrupted by TBI is a critical factor in the development of cognitive impairment.22–24 In order to explore whether rCHIMERA induced long-term white matter disintegration, we performed IHC analysis of coronal brain sections at short-term (1 and 7 days post-injury) and long-term phases (from 1 to 6.5 months post-injury) using GFAP antibody followed by chromogenic (Fig. 2) or immunofluorescence detection (Fig. 3). The representative GFAP immunostaining for coronal sections from sham, rCHIMERA-1 day, rCHIMERA-3.5 months, and rCHIMERA-6.5 months mouse brains is shown in Fig. 2A. Extensive astrocyte activation was observed in various brain regions of rCHIMERA mice at both phases, particularly in the OT, CC, HP, and CX. GFAP expression in those ROIs was significantly increased by rCHIMERA at 1 day, and 3.5 and 6.5 months (Fig. 2B). All ROIs were further verified by immunofluorescence staining using GFAP antibody (Fig. 3A), and the reactive astrocytes observed after rCHIMERA were quantified (Fig. 3B). GFAP immunofluorescence intensity was significantly higher in all of ROIs of rCHIMERA-inflicted brains from day 1, and remained elevated at 6.5 months after injury. These data indicated that astrogliosis induced by rCHIMERA is widespread and persistent at least up to 6.5 months post-injury.

FIG. 2.

Repeated closed-head impact model of engineered rotational acceleration (rCHIMERA) induced astrocyte activation in multiple brain regions. Sections of brains from rCHIMERA and sham mice were stained with GFAP. Regions of interest (ROIs) are indicated by black rectangles in the images of whole sections, and representative high magnified images of activated astrocyte cells in ROIs are shown from sham, and rCHIMERA mice at acute (1 day) and chronic time phases (3.5 and 6.5 months) (n = 3/group) (A). Optic tract (OT, scale bar: 100 μm), cortex (CX, scale bar: 50 μm), hippocampus (HP, scale bar: 50 μm), and corpus callosum (CC, scale bar: 50 μm). Quantitative data of GFAP expression in the ROIs were analyzed by two way ANOVA following a Tukey's multiple comparisons post-hoc test (B). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05).

FIG. 3.

Repeated closed-head impact model of engineered rotational acceleration (rCHIMERA) caused persistent astrogliosis. Immunofluorescence staining using GFAP antibody was performed to confirm the results of immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining in ROIs from rCHIMERA and sham mice at more time points after injury. Representative microscopic images from sham and 1 day, 7 days, 1 month, 2 months, 3.5 months, and 6.5 months post-rCHIMERA in optic tract (OT, scale bar: 500 μm), cortex (CX, scale bar: 500 μm), hippocampus (HP, scale bar: 500 μm), and corpus callosum (CC, scale bar: 100 μm), respectively (n = 4/group) (A). Quantitative analysis of GFAP expression in each of the ROIs was performed with one way ANOVA with correction for multiple comparisons following a Tukey's post-hoc test (B). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05).

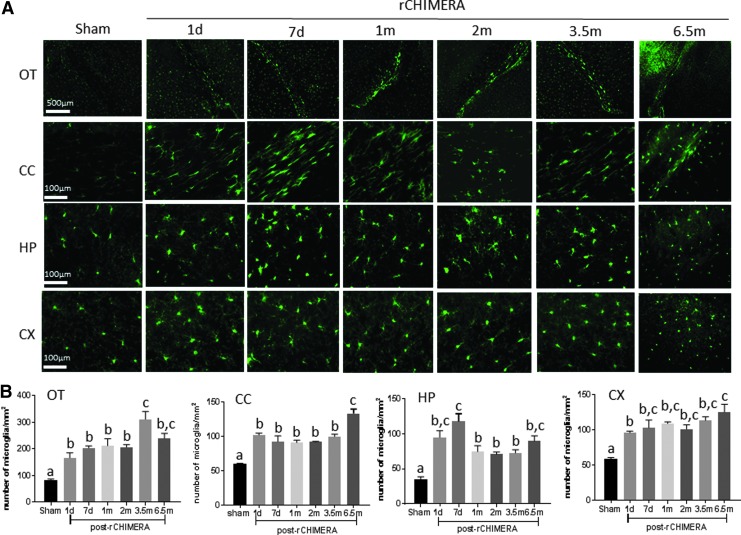

rCHIMERA also caused persistent microgliosis

Microglia as immune cells in the central nervous system (CNS) play a critical role in neuroinflammation following TBI.25 Microglia cells are rapidly activated in response to TBI, which can persist if the injury is severe or repeated. Activated microglia were observed by IHC staining using Iba-1 antibody in multiple regions of the brain at acute and chronic time windows after rCHIMERA (Fig. 4A). High magnification images showed hypertrophic ameboid microglia in the OT, CC, HP, and CX of rCHIMERA-injured mouse brains, whereas the resting state microglia showing ramified and branched processes were detected in sham mouse brains. Quantitative analysis of Iba-1-positive microglia cells by immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 5A) showed that rCHIMERA significantly increased the number of Iba-1-positve microglia cells in OT, CC, HP, and CX regions at all time points examined (Fig. 4B and 5B). These data demonstrated that rCHIMERA also induced persistent microgliosis in multiple brain regions.

FIG. 4.

Repeated closed-head impact model of engineered rotational acceleration (rCHIMERA) induced microglia activation in multiple brain regions. Images of whole sections of Iba-1 immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining with regions of interest (ROIs) indicated by black rectangles and representative 40 × magnified images of Iba-1 staining in the ROIs from sham and rCHIMERA-injured mouse brains are shown at acute (1 day) and chronic (3.5 and 6.5 months) time phases after the last injury (n = 3/group) (A). Data were analyzed by two way ANOVA following a Tukey multiple comparisons post-hoc test (B). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05). OT, optic tract; CC, corpus callosum; HP, hippocampus; CX, cortex.

FIG. 5.

Repeated closed-head impact model of engineered rotational acceleration (rCHIMERA) caused persistent microgliosis. Iba-1 immunofluorescence staining was used to confirm the results of immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining in the regions of interest (ROIs) post-rCHIMERA. Representative microscopic images from sham and 1 day, 7 days, 1 month, 2 months, 3.5 months, and 6.5 months post-rCHIMERA (n = 4/group) are shown in (A). Quantitative analysis of Iba-1 expression in each of the ROIs (B). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05). OT, optic tract; CC, corpus callosum; HP, hippocampus; CX, cortex.

rCHIMERA increased GFAP and Iba-1 protein levels

In order to verify the immunostaining results shown in Figures 2–5, we performed Western blot analysis for GFAP and Iba-1 in cortical and hippocampal homogenates at 1 month and 6.5 months after injury. Both GFAP and Iba-1 proteins were significantly elevated in these brain regions of rCHIMERA-injured mice compared with the sham group (Fig. 6A and B), confirming the immunostaining data. Hyperphosphorylated tau in the brain is involved in repetitive TBI26 and other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease (AD).27 We also measured phospho-tau protein level in those areas from sham and rCHIMERA mice at 6.5 months after injury. Phospho-tau was not affected by rCHIMERA in any of the areas (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

Repeated closed-head impact model of engineered rotational acceleration (rCHIMERA) increased GFAP and Iba-1 protein levels. Western blotting analysis was performed using homogenates from the cerebral cortex (CX) and hippocampus (HP) of sham (S) and rCHIMERA (T) mice at 1 month and 6.5 months after the last injury (n = 4/group). Representative immunoblots along with the relative quantification of GFAP (A) and Iba-1(B) in the left panel (1 month) and the right panel (6 months) are shown. (C) The immunoblot and quantification of phospho-tau protein at 6.5 months after sham and rCHIMERA. GAPDH was used as the loading control. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001 versus sham.

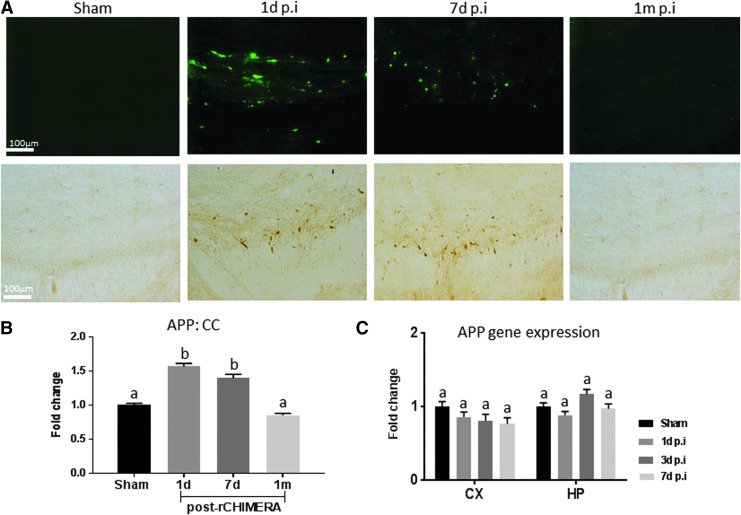

rCHIMERA induced transient APP deposition in the CC

Deposition of APP and amyloid-β has been traditionally used not only in the diagnosis of AD but also as an indicator for diffuse axonal injury.28 We assessed APP expression in rCHIMERA-injured mouse brains by immunostaining and qRT-PCR. APP immune-reactive axons appeared as large spheroid bulbs with varicose appearance in injured CC on days 1 and 7 post-rCHIMERA, but were not visible at 1 month after injury (Fig. 7A). Consistently, quantitative analysis of APP intensity in the CC indicated that rCHIMERA significantly increased APP on days 1 and 7 after injury, which returned to normal at 1 month (Fig. 7B) (p < 0.01 vs. sham). APP gene expression level in the CX and HP of the injured brain was not affected by rCHIMERA at all time points (Fig.7C), indicating that APP expression was affected by rCHIMERA at the protein level.

FIG. 7.

Repeated closed-head impact model of engineered rotational acceleration (rCHIMERA) resulted in APP deposition in the corpus callosum (CC). APP immunoreactive axons displayed axonal terminal bulbs and varicose morphology in the CC of rCHIMERA mice on days 1 and 7 after the last injury (A, top panel: immunofluorescence-staining; lower panel: 3,3′-diaminobenzidine [DAB] staining). These pathological features were absent in the sham mice and were resolved by 1 month after injury (n = 4/group) (A). APP in the CC was significantly increased on days 1 and 7, and diminished at 1 month following injury. (B) APP gene expression level in the cortex (CX) and hippocampus (HP) was not altered by rCHIMERA injury at all time points (C). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05).

rCHIMERA acutely increased GFAP and TNF-α gene expression

To determine whether proinflammatory gene expression by rCHIMERA contributes to long-lasting neuroinflammation, we measured GFAP, Iba-1, and TNF-α gene levels in the CX and HP on days 1, 3, and 7 post-rCHIMERA. GFAP and TNF-α gene expression was acutely upregulated on day 1 post-injury in both brain regions, but normalized by day 3 (Fig. 8A and B), except for GFAP expression in the hippocampus, where its expression remained elevated up to 3 days after injury (Fig. 8A). The long-term elevation of GFAP gene expression may have a role in prolonged neuroinflammation after injury. Iba-1 gene expression was not significantly altered by rCHIMERA (Fig. 8C).

FIG. 8.

Repeated closed-head impact model of engineered rotational acceleration (rCHIMERA) increased GFAP and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α gene expression. GFAP gene expression was upregulated in the cortex (CX) and hippocampus (HP) on day 1, and in the HP on days 3 and 7 post-injury compared with sham (n = 4/group) (A). TNF-α gene expression was elevated in the CX and HP on day 1, but not on days 3 and 7 post-injury (B). Iba-1 gene expression in both regions was not changed at all time points following injury (C). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we established an animal model of rmTBI that produces long-term neuropathological and functional consequences using rCHIMERA. We found that mice receiving a repeated daily impact of CHIMERA at 0.6 J yielded LRR and transient motor deficit without comorbid skull fracture, hematoma, overt brain destruction, apnea, or death. These results indicate that the CHIMERA model is well controlled and adjustable to fulfill the criteria of mTBI.29

The water maze performance was poorer for the rCHIMERA-injured mice at 1 and 6 months after injury (Fig. 1). The time to platform over the 4 days of training was longer for the mice with repeated injuries by CHIMERA (Fig. 1C,D). The average swim speed of the rCHIMERA mice was not significantly different from that of the sham group, except for the 4th day of training at 1 month after injury, when injured mice showed slower speed than the sham controls. Although it is difficult to clarify the reason for this particular exception, it is possible that the repeated injuries made the mice more susceptible to the effects of stress and/or induced changes in motivation. At 6 months after injury, however, delayed time to find the platform was still observed in the injured mice without significant differences in the average swim speed. Further, the probe tests at both time points (1 and 6 months) after injury revealed no preference for the target quadrant by the injured mice. These observations consistently suggest that repeated injuries by CHIMERA lead to lasting deficits in learning and memory. The increase in gliosis observed in the optic tract in the rCHIMERA mice (Figs. 2–5) may be a caveat for the present study. However, increased inflammation of the optic tract may not necessarily impair vision. For example, in a similar paradigm to the present study, three repeated closed head injuries with a 24 h interval using the weight drop model resulted in damage to the visual tract without compromising sensorimotor or vision faculties.30

In response to injury, astrocytes and microglia can be regarded as a double-edged sword playing either neuroprotective or deleterious roles under distinctive activated states. In acute lesions, they play a neuroprotective role by phagocytosing damaged cells and debris. However, if the pathological stimulus persists, astrocyte and microglial activation continues to release neurotransmitters and cytokines, leading to scar tissue and chronic neuroinflammation that inhibits neurite growth, neurogenesis, and neural circuitry.31,32 rmTBI and neurodegenerative disorders share similar neuropathological features including chronic neuroinflammation, widespread astrogliosis and microgliosis, and deposition of amyloid-β, its precursor APP and neurofilament phospho-tau tangles.33–35 In our rCHIMERA model, activated astrocytes and microglia were widely observed not only near the impact site, CC, and HP, but also away from the impact site, OT, and CX, up to 6.5 months after injury (Figs. 2–5). Similarly, the protein levels of GFAP and Iba-1 in the cortex and hippocampus also were increased at 1 and 6.5 months after injury (Fig 6A and B). The widespread and persistent astrogliosis and microgliosis in rCHIMERA-injured brains mirrored the neuropathology observed in human TBI.36,37 Although astrocyte and microglial response to injury in CC that peaked shortly after injury was attenuated at a later time, they were still elevated compared with the sham group, indicating that the endogenous repair system could not completely resolve rCHIMERA-induced secondary injury during the entire time frame examined. Astrogliosis and microgliosis are hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases38,39 and are associated with cognitive impairment.31,40–42 Interestingly, astrogliosis and microgliosis in the OT of injured mice was not attenuated with time, indicating that this region might be one of the most vulnerable areas to rmTBI, possibly leading to visual dysfunction after TBI. Chronic visual dysfunction many years after TBI has been reported in human patients.43,44 The potential long-term effects of mild or moderate repetitive TBI has been recognized as one of the major risk factors associated with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) characterized by hyperphosphorylated tau neurofibrillary tangles.45 Our result showed that rCHIMERA did not elevate phospho-tau protein level at 6.5 months after injury in accordance with these studies (Fig. 6D),46,47 suggesting that there are still some challenges and inherent limitations in using rodent animal models to mimic human pathology of CTE.

Deposition of APP and amyloid-β in the white matter of the brain, which is regarded as a biological marker of AD, frequently occurs in human and animal brains affected by TBI.48–50 In this study, rCHIMERA resulted in transient APP deposition in the CC on days 1 and 7 without affecting APP gene expression (Fig.7). These data indicate that rCHIMERA injury only leads to acute and local APP accumulation in the CC, which is in agreement with other mouse models of diffuse injury.51,52 This may be the result of activated microglia rapidly clearing APP at the beginning stage of rCHIMERA.53,54 This phenomenon may also explain why wild-type rodents do not exhibit a progressive process of developing neurodegenerative pathology with aging even after they are subjected to severe TBI. Further studies will be needed to understand the relationship and mechanism between rmTBI and the development of neurodegenerative conditions such as AD at a later stage in life.

TBI or rmTBI induces rapid and chronic neuroinflammatory responses by increasing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from activated microglia and astrocytes.55–57 Recently, studies in human TBI demonstrated that GFAP and its breakdown products in patient serum were good biomarkers to detect the injury severity.58–60 Interestingly, rCHIMERA injury leads to persistent reactive astrocytes, with elevated GFAP protein and gene levels in both the CX and HP regions until at least 6.5 months after injury. Currently, it is not certain whether astrogliosis plays a beneficial or a detrimental role in the long-term consequences of rCHIMERA. According to our data, learning and memory deficits at 1 and 6 months after injury (Fig. 1C and D) were observed along with persistent astroglial activation in the CX and HP in the injured brains (Figs. 2 and 3), suggesting that reactive astrocytes may play an important role in rCHIMERA-induced chronic neuropathology and cognitive impairments. The morphology of microglia (Figs. 4 and 5) and Iba-1 protein level (Fig. 6B) were dramatically affected by rCHIMERA, although the gene level did not change (Fig. 8). It is well known that microglia are the primary resident immune cells for innate immunity in the CNS. They are under constant surveillance under physiological and pathological conditions and rapidly change phenotype to respond to diverse microenvironmental signals.61,62 More studies will be needed to explore the relevance of glial activation to rCHIMERA-induced neuropathology and cognitive impairments.

Conclusion

The present study provides evidence that rCHIMERA is a mouse model that recapitulates some of the important clinical features of human rmTBI such as transient motor deficit, long-term learning and memory impairments, persistent astrogliosis and microgliosis, and neuroinflammation. However, the absence of chronic axonal degeneration and abnormal deposition of phospho-tau neurofibrillary tangle, which frequently occur in human rmTBI, is the limitation of this study. In conclusion, the rCHIMERA model established in this study presents a valuable tool to investigate some of the long-term consequences of human rmTBI and to explore effective treatment strategy for those chronic complications.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Intramural Program of the NIAAA, the NIH, and the Department of Defense in the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine. The authors thank the NIAAA animal facility staff for their support.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Barrio J.R., Small G.W., Wong K.P., Huang S.C., Liu J., Merrill D.A., Giza C.C., Fitzsimmons R.P., Omalu B., Bailes J., and Kepe V. (2015). In vivo characterization of chronic traumatic encephalopathy using [F-18]FDDNP PET brain imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci.U.S.A. 112, E2039–2047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardner R.C, and Yaffe K. (2015). Epidemiology of mild traumatic brain injury and neurodegenerative disease. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 66, 75–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerberding J.L., and Binder S. (2003). Report to Congress on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Steps to Prevent a Serious Public Health Problem. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson V.E., Stewart J.E., Begbie F.D., Trojanowski J.Q., Smith D.H., and Stewart W. (2013). Inflammation and white matter degeneration persist for years after a single traumatic brain injury. Brain 136, 28–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams S., Raghupathi R., MacKinnon M.A., McIntosh T.K., Saatman K.E., and Graham D.I. (2001). In situ DNA fragmentation occurs in white matter up to 12 months after head injury in man. Acta Neuropathol. 102, 581–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKee A.C., Daneshvar D.H., Alvarez V.E., and Stein T.D. (2014). The neuropathology of sport. Acta Neuropathol. 127, 29–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson V.E., Stewart W., and Smith D.H. (2012). Widespread tau and amyloid-beta pathology many years after a single traumatic brain injury in humans. Brain Pathol. 22, 142–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haarbauer–Krupa J., Taylor C.A., Yue J.K., Winkler E.A., Pirracchio R., Cooper S.R., Burke J.F., Stein M.B. and Manley G.T. (2016). Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder in a civilian emergency department population with traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 34, 50–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardner R.C., Burke J.F., Nettiksimmons J., Goldman S., Tanner C.M., and Yaffe K. (2015). Traumatic brain injury in later life increases risk for Parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 77, 987–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schretlen D.J. and Shapiro A.M. (2003). A quantitative review of the effects of traumatic brain injury on cognitive functioning. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 15, 341–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belanger H.G., Curtiss G., Demery J.A., Lebowitz B.K., and Vanderploeg R.D. (2005). Factors moderating neuropsychological outcomes following mild traumatic brain injury: a meta–analysis. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 11, 215–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belanger H.G., and Vanderploeg R.D. (2005). The neuropsychological impact of sports-related concussion: a meta-analysis. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 11, 345–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mangels J.A., Craik F.I., Levine B., Schwartz M.L., and Stuss D.T. (2002). Effects of divided attention on episodic memory in chronic traumatic brain injury: a function of severity and strategy. Neuropsychologia 40, 2369–2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernstein D.M. (2002). Information processing difficulty long after self-reported concussion. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 8, 673–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraus M.F., Little D.M., Donnell A.J., Reilly J.L., Simonian N., and Sweeney J.A. (2007). Oculomotor function in chronic traumatic brain injury. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 20, 170–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ponsford J., McLaren A., Schonberger M., Burke R., Rudzki D., Olver J., and Ponsford M. (2011). The association between apolipoprotein E and traumatic brain injury severity and functional outcome in a rehabilitation sample. J. Neurotrauma 28, 1683–1692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander S., Kerr M.E., Kim Y., Kamboh M.I., Beers S.R., and Conley Y.P. (2007). Apolipoprotein E4 allele presence and functional outcome after severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 24, 790–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loane D.J., Stoica B.A., and Faden A.I. (2015). Neuroprotection for traumatic brain injury. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 127, 343–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marklund N., and Hillered L. (2011). Animal modelling of traumatic brain injury in preclinical drug development: where do we go from here? British journal of pharmacology 164, 1207–1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong Y., Mahmood A., and Chopp M. (2013). Animal models of traumatic brain injury. Nature reviews. Neuroscience 14, 128–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Namjoshi D.R., Cheng W.H., McInnes K.A., Martens K.M., Carr M., Wilkinson A., Fan J., Robert J., Hayat A., Cripton P.A. and Wellington C.L. (2014). Merging pathology with biomechanics using CHIMERA (closed-head impact model of engineered rotational acceleration): a novel, surgery-free model of traumatic brain injury. Mol. Neurodegener. 9, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinnunen K.M., Greenwood R., Powell J.H., Leech R., Hawkins P.C., Bonnelle V., Patel M.C., Counsell S.J., and Sharp D.J. (2011). White matter damage and cognitive impairment after traumatic brain injury. Brain 134, 449–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraus M.F., Susmaras T., Caughlin B.P., Walker C.J., Sweeney J.A., and Little D.M. (2007). White matter integrity and cognition in chronic traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Brain 130, 2508–2519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niogi S.N., Mukherjee P., Ghajar J., Johnson C., Kolster R.A., Sarkar R., Lee H., Meeker M., Zimmerman R.D., Manley G.T., and McCandliss B.D. (2008). Extent of microstructural white matter injury in postconcussive syndrome correlates with impaired cognitive reaction time: a 3T diffusion tensor imaging study of mild traumatic brain injury. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 29, 967–973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar A., and Loane D.J. (2012). Neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury: opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Brain Behav. Immun. 26, 1191–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puvenna V., Engeler M., Banjara M., Brennan C., Schreiber P., Dadas A., Bahrami A., Solanki J., Bandyopadhyay A., Morris J.K., Bernick C., Ghosh C., Rapp E., Bazarian J.J., and Janigro D. (2016). Is phosphorylated tau unique to chronic traumatic encephalopathy? Phosphorylated tau in epileptic brain and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain Res. 1630, 225–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu K.P., Kondo A., Albayram O., Herbert M.K., Liu H., and Zhou X.Z. (2016). Potential of the antibody against cis-phosphorylated tau in the early diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Alzheimer disease and brain injury. J.A.M.A. Neurol. 73, 1356–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marklund N., Farrokhnia N., Hanell A., Vanmechelen E., Enblad P., Zetterberg H., Blennow K., and Hillered L. (2014). Monitoring of beta-amyloid dynamics after human traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 31, 42–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carroll L.J., Cassidy J.D., Holm L., Kraus J., and Coronado V.G. (2004). Methodological issues and research recommendations for mild traumatic brain injury: the WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Inj. 43 Suppl, 113–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Creeley C.E., Wozniak D.F., Bayly P.V., Olney J.W., and Lewis L.M. (2004). Multiple episodes of mild traumatic brain injury result in impaired cognitive performance in mice. Acad. Emerg. Med. 11, 809–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sajja V.S., Hlavac N., and VandeVord P.J. (2016). Role of glia in memory deficits Following traumatic brain injury: biomarkers of glia dysfunction. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 10, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aihara N., Hall J.J., Pitts L.H., Fukuda K., and Noble L.J. (1995). Altered immunoexpression of microglia and macrophages after mild head injury. J. Neurotrauma 12, 53–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tran H.T., LaFerla F.M., Holtzman D.M., and Brody D.L. (2011). Controlled cortical impact traumatic brain injury in 3xTg-AD mice causes acute intra-axonal amyloid-beta accumulation and independently accelerates the development of tau abnormalities. J. Neurosci. 31, 9513–9525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trinchese F., Liu S., Battaglia F., Walter S., Mathews P.M., and Arancio O. (2004). Progressive age-related development of Alzheimer-like pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Ann. Neurol. 55, 801–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith D.H., Johnson V.E., and Stewart W. (2013). Chronic neuropathologies of single and repetitive TBI: substrates of dementia? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9, 211–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beschorner R., Nguyen T.D., Gozalan F., Pedal I., Mattern R., Schluesener H.J., Meyermann R., and Schwab J.M. (2002). CD14 expression by activated parenchymal microglia/macrophages and infiltrating monocytes following human traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathol. 103, 541–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gentleman S.M., Leclercq P.D., Moyes L., Graham D.I., Smith C., Griffin W.S., and Nicoll J.A. (2004). Long-term intracerebral inflammatory response after traumatic brain injury. Forens. Sci. Int. 146, 97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hennessy E., Griffin E.W. and Cunningham C. (2015). Astrocytes are primed by chronic neurodegeneration to produce exaggerated chemokine and cell infiltration responses to acute stimulation with the cytokines IL-1beta and TNF-alpha. J. Neurosci. 35, 8411–8422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hibbits N., Yoshino J., Le T.Q., and Armstrong R.C. (2012). Astrogliosis during acute and chronic cuprizone demyelination and implications for remyelination. ASN Neuro 4, 393–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calabrese E., Du F., Garman R.H., Johnson G.A., Riccio C., Tong L.C., and Long J.B. (2014). Diffusion tensor imaging reveals white matter injury in a rat model of repetitive blast-induced traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 31, 938–950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sajja V.S., Perrine S.A., Ghoddoussi F., Hall C.S., Galloway M.P., and VandeVord P.J. (2014). Blast neurotrauma impairs working memory and disrupts prefrontal myo-inositol levels in rats. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 59, 119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sajja V.S., Ereifej E.S. and VandeVord P.J. (2014). Hippocampal vulnerability and subacute response following varied blast magnitudes. Neurosci. Lett. 570, 33–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brahm K.D., Wilgenburg H.M., Kirby J., Ingalla S., Chang C.Y., and Goodrich G.L. (2009). Visual impairment and dysfunction in combat-injured servicemembers with traumatic brain injury. Optom. Vis. Sci. 86, 817–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goodrich G.L., Martinsen G.L., Flyg H.M., Kirby J., Garvert D.W., and Tyler C.W. (2014). Visual function, traumatic brain injury, and posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 51, 547–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKee A.C., Stein T.D., Kiernan P.T., and Alvarez V.E. (2015). The neuropathology of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain Pathol. 25, 350–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mouzon B.C., Bachmeier C., Ferro A., Ojo J.O., Crynen G., Acker C.M., Davies P., Mullan M., Stewart W., and Crawford F. (2014). Chronic neuropathological and neurobehavioral changes in a repetitive mild traumatic brain injury model. Ann. Neurol. 75, 241–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu L., Nguyen J.V., Lehar M., Menon A., Rha E., Arena J., Ryu J., Marsh–Armstrong N., Marmarou C.R., and Koliatsos V.E. (2016). Repetitive mild traumatic brain injury with impact acceleration in the mouse: multifocal axonopathy, neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration in the visual system. Exp. Neurol. 275, Pt., 3, 436–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marklund N., Blennow K., Zetterberg H., Ronne–Engstrom E., Enblad P. and Hillered L. (2009). Monitoring of brain interstitial total tau and beta amyloid proteins by microdialysis in patients with traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 110, 1227–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zetterberg H., Blennow K., and Hanse E. (2010). Amyloid beta and APP as biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease. Exp. Gerontol. 45, 23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Itoh T., Satou T., Nishida S., Tsubaki M., Hashimoto S,. and Ito H. (2009). Expression of amyloid precursor protein after rat traumatic brain injury. Neurol. Res. 31, 103–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Creed J.A., DiLeonardi A.M., Fox D.P., Tessler A.R., and Raghupathi R. (2011). Concussive brain trauma in the mouse results in acute cognitive deficits and sustained impairment of axonal function. J. Neurotrauma 28, 547–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lowing J.L., Susick L.L., Caruso J.P., Provenzano A.M., Raghupathi R., and Conti A.C. (2014). Experimental traumatic brain injury alters ethanol consumption and sensitivity. J. Neurotrauma 31, 1700–1710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stalder M., Deller T., Staufenbiel M., and Jucker M. (2001). 3D-Reconstruction of microglia and amyloid in APP23 transgenic mice: no evidence of intracellular amyloid. Neurobiol. Aging 22, 427–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paresce D.M., Chung H., and Maxfield F.R. (1997). Slow degradation of aggregates of the Alzheimer's disease amyloid beta-protein by microglial cells. J Biol. Chem. 272, 29390–29397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Loane D.J., and Kumar A. (2016). Microglia in the TBI brain: the good, the bad, and the dysregulated. Exp. Neurol. 275 Pt 3, 316–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chio C.C., Chang C.H., Wang C.C., Cheong C.U., Chao C.M., Cheng B.C., Yang C.Z., and Chang C.P. (2013). Etanercept attenuates traumatic brain injury in rats by reducing early microglial expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. BMC Neurosci. 14, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morganti–Kossmann M.C., Satgunaseelan L., Bye N. and Kossmann T. (2007). Modulation of immune response by head injury. Injury 38, 1392–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Papa L., Brophy G.M., Welch R.D., Lewis L.M., Braga C.F., Tan C.N., Ameli N.J., Lopez M.A., Haeussler C.A., Mendez Giordano D.I., Silvestri S., Giordano P., Weber K.D., Hill–Pryor C., and Hack D.C. (2016). Time course and diagnostic accuracy of glial and neuronal blood biomarkers GFAP and UCH-L1 in a large cohort of trauma patients with and without mild traumatic brain injury. JAMA Neurol. 73, 551–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McMahon P.J., Panczykowski D.M., Yue J.K., Puccio A.M., Inoue T., Sorani M.D., Lingsma H.F., Maas A.I., Valadka A.B., Yuh E.L., Mukherjee P., Manley G.T., and Okonkwo D.O. (2015). Measurement of the glial fibrillary acidic protein and its breakdown products GFAP-BDP biomarker for the detection of traumatic brain injury compared to computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J. Neurotrauma 32, 527–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Diaz–Arrastia R., Wang K.K., Papa L., Sorani M.D., Yue J.K., Puccio A.M., McMahon P.J., Inoue T., Yuh E.L., Lingsma H.F., Maas A.I., Valadka A.B., Okonkwo D.O., and Manley G.T. (2014). Acute biomarkers of traumatic brain injury: relationship between plasma levels of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 and glial fibrillary acidic protein. J. Neurotrauma 31, 19–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang G., Zhang J., Hu X., Zhang L., Mao L., Jiang X., Liou A.K., Leak R.K., Gao Y. and Chen J. (2013). Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics in white matter after traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 33, 1864–1874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hu X., Li P., Guo Y., Wang H., Leak R.K., Chen S., Gao Y., and Chen J. (2012). Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics reveal novel mechanism of injury expansion after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 43, 3063–3070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]