Abstract

We estimate the long-run impact of cash transfers to poor families on children’s longevity, educational attainment, nutritional status, and income in adulthood. To do so, we collected individual-level administrative records of applicants to the Mothers’ Pension program—the first government-sponsored welfare program in the United States (1911–1935)—and matched them to census, WWII, and death records. Male children of accepted applicants lived one year longer than those of rejected mothers. They also obtained one-third more years of schooling, were less likely to be underweight, and had higher income in adulthood than children of rejected mothers.

More than 20 percent of children in the United States were living in poverty as recently as 2010.1 A growing literature documents the adverse long-term effects of early-life exposure to disease, nutritional deprivation, and other factors associated with poverty on educational attainment, labor market outcomes, and ultimately, mortality (Almond and Currie 2011b). In the United States and elsewhere, welfare programs—broadly defined as cash transfers to poor families—were established primarily to help children. While parental income has been shown to be one of the strongest predictors of children’s educational attainment (Barrow and Schanzenbach 2012; Reardon 2011) and health in adulthood (Case, Lubotsky, and Paxson 2002), it is still unknown whether these cash transfers provide lifelong benefits for children raised in poor families (Currie 1998).

There are multiple reasons why means-tested cash transfers could fail to help poor children: the amounts given may be insufficient; parents might not use the transfer in ways that benefit their children, or might use the transfers inefficiently due to poor information (Dizon-Ross 2014). The program could also induce parental behavioral responses that are potentially detrimental to the child, altering their labor supply, fertility, or probability of remarriage. While a large literature considers parental responses to welfare receipt (Moffitt 1998), little is known about the overall impact of the transfers on the lifetime outcomes of the children of beneficiaries.

One of the main difficulties in evaluating whether cash transfers (or any public program) improve outcomes is identifying a plausible counterfactual: what would children’s lives have been like in the absence of receiving transfers? The other difficulty lies in obtaining data on long-term outcomes for a large sample of recipients and plausible comparison groups. Survey datasets such as the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) and Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) include only a small number of welfare recipients from recent cohorts and, moreover, suffer from substantial attrition.2 Individual-level administrative records from the early years of the Aid to Dependent Children (ADC) program (1935–1962) have been lost or intentionally destroyed. Although records do exist for recipients of Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC, the program that replaced ADC in 1962), these cohorts are too young for us to evaluate the impact of welfare participation on their longevity. Recent cohorts of recipients are also problematic because recipients tend to be eligible for many other transfers, such as Medicaid, housing assistance, and food stamps, thus making it difficult to evaluate the impact of cash transfers alone.3

To overcome these challenges, we collected administrative records from the precursor to the ADC program; the Mothers’ Pension program (1911–1935), which was the first US government-sponsored welfare program for poor mothers with dependent children.4 The intent of the MP program was to improve the conditions of “young children that have become dependent through the loss or disability of the breadwinner” (Abbott 1933, p. 1). The transfers generally represented 12–25 percent of family income, and typically lasted for three years. To look at the impact of these transfers, we track longevity and other outcomes of the children whose mothers applied to the program. These data include information on thousands of accepted and rejected applicants born between 1900 and 1925, most of whom had died by 2012. The identifying information in the application records allows us to link the children with other datasets to trace their lifetime outcomes.

For identification, we use as a comparison group children of mothers who applied for transfers and who were initially deemed eligible, but were denied upon further investigation. This strategy of comparing accepted and rejected applicants for program evaluation has been used successfully in studies of disability insurance (von Wachter, Song, and Manchester 2011; Bound 1989). Its validity depends on the extent to which accepted and rejected mothers and their children differ on unobservable characteristics. We document that rejected mothers were on average slightly better-off, based on observable characteristics at the time of application. We also match two subsamples of recipients to pre-application characteristics in the federal censuses (1900–1920) and in the 1915 Iowa State Census. Though the samples are smaller, we find that rejected applicants came from richer families: they had higher incomes, were more likely to own their homes, and conditional on homeownership, their homes were of greater value. These data are consistent with the information in our administrative records, which report that applicants were rejected most often because they were deemed to have sufficient support. Our findings are also in line with the few available historical accounts of these records. Finally, we directly investigate whether discrimination on the basis of race or nativity can explain our findings and conclude that they do not. Under the assumption that accepted and rejected applicants are otherwise similar, the outcomes for boys of rejected mothers provide a best-case scenario (upper bound) for what could be expected of beneficiaries in the absence of transfers.

Using data collected on over 16,000 boys from 11 states, who were born between 1900 and 1925, and whose mothers applied to the Mothers’ Pension program, we find that receiving cash transfers increased longevity by about 1 year. This effect is greater for the poorest families in the sample: their longevity increased by 1.5 years of life. These results are very robust to alternative functional form specifications, alternative counterfactual comparisons (e.g., comparing eligible and ineligible families), and our treatment of attrition. Because income transfers were the only major public benefit that poor children were eligible for until 1950 (with the exception of public schooling), we can interpret our results as the effect of cash transfers alone.

To investigate potential mechanisms behind the positive effect on longevity, we match a subset of our records to WWII enlistment and 1940 census records. The results suggest that cash transfers reduced the probability of being underweight by half, increased educational attainment by 0.34 years, and increased income in early adulthood by 14 percent. Previous work has documented that all three measures (being underweight, income, and education) are independently associated with mortality (Flegal et al. 2005; Deaton and Paxson 2001; Cutler and Lleras-Muney 2008). A back of the envelope calculation based on estimates from these studies suggests that at least 75 percent of the observed increase in longevity can be explained by these three mechanisms.

Our analysis has some important limitations. We cannot examine outcomes for women because they typically changed their name upon marriage, making it extremely difficult to track long-term outcomes through sources that can be linked only with the consistent reporting of names. Nor can we study African-Americans because they are not well represented in our states or our data samples. Finally, though our results are based on larger samples with lower attrition than current panel surveys, there is still attrition in our sample. However, for a subset of our sample we were able to collect additional data, thereby significantly reducing attrition, and the results remain unchanged, thus suggesting that attrition is not influencing our results.

We conclude that cash transfers to poor families during the first part of the twentieth century ameliorated early life conditions enough to improve both medium- and long-term outcomes of boys growing up in poverty. While conditions today differ significantly from those at the beginning of the twentieth century, which causes us to be cautious of drawing conclusions regarding the anticipated impact of cash transfers in the twenty-first century, it is still the case that the historical evidence constitutes the best available means to assess the impact of cash transfers across the life course. Moreover, three important similarities remain. First, both the MP program and current welfare programs target children in female-headed households—and we document that these children were, and continue to be, the poorest children in the population. Second, historical comparisons presented in the concluding section suggest that family income plays an important role in producing positive child outcomes, both today and at the beginning of the twentieth century, when the MP program operated. Finally, our short- and medium-term effects on education and health are consistent with contemporary evidence on the effect of poverty-reduction programs in the United States and in developing countries. Together these results suggest that targeted cash transfers are also likely to improve lifetime outcomes today. We return to the related literature and policy implications in the final section of the paper.

I. Mothers’ Pension Programs: History and Characteristics

The MP program was a needs-based program, established on a state-by-state basis between 1911 and 1931. When it was replaced by ADC in 1935, 200,000 children were receiving MP benefits (Katz 1996). Several factors prompted the enactment of MP legislation. At the time, children of destitute parents were routinely sent to orphanages, and these children were thought to fare very poorly.5 Moreover, among those who remained with their mothers, prominent judges of juvenile courts argued that maternal absence, due to full-time employment, was the main reason why many of these children became delinquent.6 MP programs were seen as a cheaper and better alternative for children since income transfers would allow mothers to care for their children at home.7 There was also a growing sense that poverty was not being adequately addressed by private charity. The spirit of the legislation is well captured in Colorado’s law: “This act shall be liberally construed for the protection of the child, the home and the states and in the interest of public morals, and for the prevention of poverty and crime” (Lindsey 1913, p. 716).

States had complete discretion in establishing an MP program, setting eligibility criteria, and providing funding. Online Appendix Table S1 shows the details of the MP laws for all states with MP programs.8 This information is available from various publications for years 1914, 1916, 1919, 1922, 1925, 1926, 1929, and 1934 (see online Appendix II for sources). Below we describe how the programs varied in terms of eligibility, generosity, duration, and conditions for receipt in 1922, the median application year in our data.

Eligibility

All states required the mother to be poor, though neither income nor property thresholds were specified. States also required the husband to be either missing or incapacitated (physically or mentally) and while poor widows were eligible everywhere, states varied with respect to their treatment of deserted or divorced women and women whose husbands were in prison or hospitalized. Citizenship was not required in most states; however even in those states that required citizenship, the intention to become a citizen was sufficient to qualify (US Department of Labor, Children’s Bureau 1933). Evidence from Iowa suggests that by limiting eligibility to mothers with dependent children, the MP program succeeded in targeting the poorest children. Using data from the 1915 Iowa state census—the only individual survey of households that collected income prior to 1940—we find that boys under the age of 18 growing up in households without a married male (11 percent of all boys) were significantly poorer. They possessed half the income and were substantially more likely to be at the bottom of the income distribution than boys in households with a married male present (online Appendix Table S2).

Administration

Importantly, state MP laws only established guidelines; it was up to individual counties to create, fund, and administer their own programs. As a result, there was both substantial cross-state and within-state variation in program characteristics and implementation. For instance, many counties never implemented MP programs, despite the state law.9 Moreover, in counties with laws, eligible families were underserved: the US Department of Labor, Children’s Bureau (1926) estimated that only one-third of the targeted families received help.

Generosity

The state-legislated maximum monthly benefit for the first child varied across states, ranging from a low of $10 in Iowa, to a high of $35 in Ohio, with the total monthly amount increasing nonlinearly with the number of children in the family. In practice, generosity in benefit levels varied widely across counties within a state.10 In our records, the average transfer ranges from $10 to $30 per month. To better understand the generosity of the benefits in real terms, we compare the monthly transfers to the average wages in manufacturing in the state (online Appendix Table S3): the average monthly MP transfer was between 17 percent and 20 percent of monthly manufacturing wages.11 In a handful of counties, records of maternal income of MP recipients are available (online Appendix Table S3, column 4). Not surprisingly, maternal income was considerably lower than manufacturing wages, and relative to these lower levels, the MP transfers were more generous, representing 29–39 percent of maternal income.12 Overall the evidence suggests that while MP transfers represented a substantial source of income for poor mothers, these additional cash transfers did not elevate them to the middle class. We cannot say definitively whether or how MP transfers may have crowded-out private transfers, but the historical evidence does not support strong crowd-out.13

Duration

In most states the transfers would be given until the pension was revoked. However, five states in our sample required reapplication at intervals ranging from three months to one year (online Appendix Table S1). In our records, the median duration in an MP program among recipients is three years.

Additional Requirements or Conditions

While most states required the mother to stay at home, Illinois, Minnesota, Montana, Ohio, Oregon, and Wisconsin allowed counties to require or regulate maternal work. Many laws also explicitly required that the mother be of “good morals.” However, in the records that include information on reason for discontinuation (Table 1), there are very few instances in which a mother or child’s failure to comply with these conditions is listed as the reason for discontinuation. The most common cause of discontinuance was loss of eligibility due to remarriage. We conclude that the MP program should be viewed as an unconditional cash transfer, rather than as a transfer that was contingent on specified actions by the recipient.

Table 1.

Determinants of Acceptance and Generosity of Transfers

| Full sample

|

Matched sample

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accepted | ln(amount) | ln(duration) | Accepted | ln(amount) | ln(duration) | |

| Child age (years) | −0.00324 [0.005] | 0.00841 [0.008] | −0.0146 [0.011] | −0.00277 [0.004] | 0.00177 [0.007] | −0.0139 [0.017] |

| Length of family name | 0.00176 [0.002] | −0.000433 [0.003] | 0.00455 [0.008] | −0.000319 [0.003] | 0.00240 [0.003] | 0.00779 [0.010] |

| Family size = 2 | 0.0632*** [0.012] | 0.265*** [0.025] | 0.268*** [0.063] | 0.0349** [0.017] | 0.273*** [0.033] | 0.331*** [0.061] |

| Family size = 3 | 0.0732*** [0.014] | 0.479*** [0.034] | 0.413*** [0.064] | 0.0511*** [0.019] | 0.491*** [0.042] | 0.511*** [0.062] |

| Family size = 4 | 0.0887*** [0.020] | 0.605*** [0.046] | 0.436*** [0.063] | 0.0624*** [0.024] | 0.624*** [0.055] | 0.545*** [0.061] |

| Family size = 5 | 0.0930*** [0.026] | 0.748*** [0.052] | 0.524*** [0.083] | 0.0570* [0.032] | 0.755*** [0.061] | 0.578*** [0.092] |

| Family size = 6 | 0.0917*** [0.022] | 0.804*** [0.064] | 0.542*** [0.108] | 0.0626** [0.030] | 0.807*** [0.078] | 0.588*** [0.120] |

| Family size = 7 | 0.102*** [0.031] | 0.946*** [0.071] | 0.478*** [0.125] | 0.0654* [0.038] | 0.922*** [0.093] | 0.573*** [0.120] |

| Family size = 8 or more | 0.0587* [0.034] | 0.977*** [0.069] | 0.516*** [0.126] | 0.0704 [0.046] | 0.975*** [0.077] | 0.586*** [0.125] |

| Age of oldest kid in family | −0.00177 [0.002] | −0.00864*** [0.003] | 0.000259 [0.007] | −0.00129 [0.002] | −0.00547* [0.003] | −0.00665 [0.006] |

| Age of youngest kid in family | −0.00247 [0.002] | −0.0132* [0.003] | −0.0207* [0.007] | −0.00258 [0.002] | −0.0133* [0.003] | −0.0178** [0.007] |

| Divorced | −0.0566* [0.032] | 0.000120 [0.021] | −0.100* [0.036] | −0.0415 [0.034] | 0.00865 [0.028] | 0.0148 [0.030] |

| Husband abandoned/prison/hospital | −0.00639 [0.009] | 0.000555 [0.015] | −0.116* [0.026] | −0.00448 [0.010] | −0.00651 [0.017] | −0.0815* [0.026] |

| Mother’s marital status unknown | −0.0938 [0.061] | −0.0365 [0.032] | 0.00975 [0.086] | −0.116 [0.076] | −0.0333 [0.038] | 0.0764 [0.065] |

| Day or month of birth missing | −0.0210 [0.033] | 0.0488 [0.038] | 0.393* [0.197] | 0.0399 [0.039] | 0.0433 [0.065] | 0.356* [0.211] |

| Observations | 16,068 | 13,787 | 6,868 | 7,859 | 6,820 | 3,677 |

| Mean | 0.865 | 5.509 | 1.306 | 0.875 | 5.508 | 1.340 |

Note: Robust standard errors in brackets.

significant at the 1 percent level.

significant at the 5 percent level.

significant at the 10 percent level.

II. Data

A. MP Records

We have attempted to collect all the MP records that survive containing dates of birth and full names. Our efforts have yielded approximately 80,000 child recipients whose mothers applied to the MP program between 1911 and 1935 in 11 states: Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Montana, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Washington, and Wisconsin. These data include the full universe of families who received MP benefits in the county, state, and year. For some states, we have the full universe of counties that provided MP benefits, while for others we have only a subset of these counties; but if a county has records, the universe of records is available.

These data appear to be representative of the MP population in the states on which we focus based on a comparison of our data for 1930 with published statistics for ten of these states in 1931 (online Appendix Table S4a and Figure S5).14 For a few counties we also compared the average grants in our data with published county-level averages (online Appendix Table S4b) and verified their similarity.15

From the MP records, we observe each mother’s first and last name, the county or town of her residence, the full names of her children, their dates of birth, the reason for her application (widowed, abandoned, etc.), and whether the application was accepted or rejected. If the application is accepted, we observe the monthly amount of the pension, and dates of receipt. For some counties we have additional information, such as the reason why an applicant was rejected or the reason why transfers were discontinued. For a single county (Clay County, MN) we have data from a detailed 1930 study based on nurse visits to the homes of all 62 families in the MP program at that time.

B. Mortality Data and Matching

Each male child of every MP applicant was matched to records from the Social Security Death Master File (DMF). The DMF contains the name, date of birth, date of death, and Social Security number for 88 million individuals whose deaths were reported to the SSA from 1965 until 2012. We matched individuals based on their first, middle, and last name, as well as their day, month, and year of birth. Details of the matching procedure are in online Appendix I.

Not all individuals who died can be found because individual death records are only systematically available for the population after the mid-1970s (Hill and Rosenwaike 2001).16 Individuals who died before the mid-1970s may be in the database but the records are incomplete. Based on cohort life tables, we calculate that 72 percent, 48 percent, and 28 percent among the 1900, 1910, and 1920 cohorts are likely to have died by 1975. Also, we can only follow individuals up to 2012. The fraction of those surviving past 2012 is 0 for both 1900 and 1910 cohorts but it rises to 5.3 percent for the 1920 cohort, and to 31.5 percent for the 1930 cohort. We compare the predicted share of missing matches by cohort assuming the matches are missing only because of deaths prior to 1975 or after 2012 (online Appendix Figure S1a), with the actual share of missing matches in our data (online Appendix Figure S1b). Both show a very similar U-shaped pattern, leading us to conclude that the missing data pattern by cohort in our sample is consistent with mortality-driven attrition. However, we limit attention to cohorts born before 1925 to minimize the share of individuals that are still alive.

We were able to match 48 percent of our sample to a unique SSA death record. Four percent were linked to multiple records. Therefore, we have information on age at death for 52 percent of our sample and 48 percent had no match. Using life tables and the age at which we observe children alive and in the MP program, we computed the number of individuals who would be expected to die prior to the existence of comprehensive DMF data (around 1975). These calculations suggest that about 32 percent of those in the MP records should have died prior to the DMF; therefore we find at least one match in the DMF for more than 77 percent of the individuals whose death records should be in the DMF, assuming the MP applicants are a representative sample.17 However, given that these families are poor and existing evidence links poverty to shorter life expectancy, one would reasonably expect deaths before entry into the DMF to be higher than 32 percent, so our match rate likely exceeds the 77 percent figure. We conclude that the amount of attrition is reasonable and we use different methods to assess its influence on our results.

C. Other State and County Data

We include as controls all the time-varying characteristics of the MP laws described previously (and listed in online Appendix Table S1). We also include state-level, time-varying characteristics that we believe might have affected the existence or generosity of the program: the ratio of state manufacturing earnings to national manufacturing earnings, laws governing school attendance, and expenditures on social programs, education and charitable institutions, hospitals, and prisons.18 For Ohio in particular, we were able to obtain county-level expenditures for several years, including expenditures on total relief, outdoor relief, and children’s homes (see online Appendix II for details). These data allow us to rule out possible confounding factors and bias in the estimates (i.e., if MP program characteristics such as generosity and rejection rate are influenced by other resources available for the poor in the county).

D. Sample Selection

To maximize the quality of the matched data we made several sample restrictions. We dropped individuals without a year of birth or year of application as well as those without a first or last name. Our work and the results from the existing literature suggest that matching rates are substantially lower in the absence of this key information. For the same reasons, we did not collect county records that failed to include this information. As noted previously, we limit our analysis to males because women often change their names upon marrying and thus are substantially harder to match. We also restrict attention to cohorts born between 1900–1925 to maximize the likelihood that we find individuals in the mortality records and the likelihood that individuals have died by 2012.

We made some additional sample restrictions for data quality reasons. We dropped a few individuals older than 19 or born after the mother applied because they are very rare and information on older children or new children does not appear to have been systematically collected in the records.19 We also drop individuals whose mothers applied to the program after 1930 as we were not able to collect these records systematically since many programs were defunded during the Great Depression.20

Finally, to maximize the internal validity of the study, we exclude counties without information on rejected applicants. Online Appendix Table S5 shows the details of our sample selection and how it affects our sample size. Our final sample includes approximately 16,000 males in 75 counties from 11 states and appears to be representative of the states and counties. We present estimates of the extent to which county characteristics (based on the 1910 census and including socioeconomic index, share old, young, white, foreign born, literate, in manufacturing, and in agriculture) predict inclusion in our final sample (online Appendix Table S6). While none of the characteristics we examine is a statistically significant predictor of inclusion in our sample, the included counties had higher fractions literate and immigrant. We conclude that our final analysis sample consisting of 75 counties is generally representative of the nation at the time.

Among the 16,000 in our final sample, 14 percent were rejected applicants. In particular, the share of rejected applicants ranges from a low of 5 percent in Minnesota to a high of 17 percent in Ohio, the state from which most individuals in our sample originate (34 percent of individuals in our sample come from Ohio). The variation in rejection rates across counties is likely due to the fact that in some areas applicants were summarily rejected without filing a formal application, which led to a lower formal rejection rate. A study by Abbott and Breckinridge (1921, p. 72) of MP programs in Illinois during the 1910s states the following regarding the MP application process:

A woman who is found, upon preliminary questioning, to be plainly ineligible to [receive] a pension is not allowed to file her application. If she is destitute and ineligible for a pension, she is told that she must apply to some relief agency and is told where to go. If it is not clear that an applicant is ineligible, the application is filed, the court officer investigates and the committee, on the basis of this investigation, recommends that the application be granted or dismissed.

We investigate the comparability of accepted and rejected applicants in our records further in the sections that follow. But it is worth emphasizing that many applicants who applied but were immediately turned down are not in our records, only those who passed a preliminary evaluation are. This further supports our use of the rejected as a control as it underscores the similarities across the two groups. We are not claiming there was no discrimination against some groups in the MP program; indeed as we discussed the laws themselves often explicitly excluded nonnatives, abandoned or divorced women, working women, and those deemed of low morals. This is why we cannot (and do not) compare categorically eligible versus ineligible groups, but rather compare individuals who were both deemed eligible to apply. Nevertheless we return to the issue of comparability and discrimination, and attempt to address these issues with additional data.

III. Empirical Strategy and identification of the Effects of Transfers

A. Basic Empirical Model

We start by estimating an accelerated failure time (AFT) hazard model of the functional form

where the dependent variable is the natural log of the age at death for a given individual i in family f born in year t living in county c (state s), MPf, is defined as an indicator for whether the child’s family received MP benefits, and X is a vector of relevant family characteristics (marital status, number of siblings, etc.), and child characteristics (year of birth and age at application). We also control for county-level characteristics in 1910, and state characteristics in the year of application (Zst). In our preferred specification we also control for county fixed effects (θc) and cohort fixed effects (θt). Thus, the effect of the program θ1 is identified by comparing the average age at death of accepted boys to rejected boys within county and year of birth, conditional on other observables. Standard errors are clustered at the county-level.

B. Model to Address Attrition and Multiple Matches

This baseline specification provides a convenient summary measure of the total effect of the program on longevity. But it does not allow us to easily deal with attrition and places strong restrictions on the shape of the hazard rate. Therefore we also estimate the effect of cash transfers on outcomes using the following logit model:

where P is probability of surviving past age a for a given individual with all other covariates defined as before. We can estimate this model for all ages. And to investigate the role of attrition, we can assume that all those without a match in the DMF were deceased and set the binary indicator for survival used in equation (2) to zero for these unmatched observations. We can then compare survival regression results for the “matched sample” (where only those with unique ages at death are included) with results from the “ full-sample” where we impute a zero to those without an age at death in all our estimations. If the missing data is entirely explained by early mortality as suggested by the life tables, then the full-sample estimates will be correct. In addition to missing matches (attrition), we have multiple matches for 4 percent of our sample. We use the estimation procedures developed by Bugni, Honoré, and Lleras-Muney (2014) to account for multiple matches in the logit estimation.21

C. Evaluation of an identification Strategy Based on Rejected Applicants

For identification of causal effects, we use rejected applicants as the counter-factual, a strategy that has been used by others to estimate program impacts (e.g., Bound 1989; von Wachter et al. 2011). The rationale for using rejected applicants is that they are likely similar to recipients on observable and unobservable characteristics. Not only are they likely to face similar economic conditions at the time of application, but they are also likely to share the same level of (unobserved) factors such as “motivation” and knowledge of the MP program.22 Moreover, as explained above, they likely appeared eligible upon first examination.

We investigate here the validity of using the rejected as a counterfactual through a systematic comparison of the two groups. First, we compare the characteristics of accepted and rejected boys based on characteristics in the administrative records. Second, we match a subset of the data to census records in years prior to the date of application. These census manuscripts contain measures of income, homeownership, education, and occupation, which we use to better assess and compare the accepted to the rejected. Third, we examine the reasons for rejection and discontinuance among the two groups.

On observables, accepted and rejected applicants look similar but not identical. On average, rejected applicants were slightly older and came from slightly smaller families. For rejected applicants, the average age of the children in the family was higher, particularly the age of the youngest child (see Table 2A for a comparison of means and online Appendix Figure S2 for a comparison of distributions). That courts rejected families with children of, or close to, working age as well as families with only a single child is consistent with qualitative evidence on the rejection of families because they were considered in less need of support. Widowhood (the omitted category) was also more predictive of both acceptance and duration most likely because it was considered more permanent than paternal imprisonment or hospitalization, the two most common other sources of eligibility, and also because widowed women were generally poorer (online Appendix Table S2).

Table 2.

| A—Summary Statistics for Estimation Samples

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample

|

Sample matched to unique age at death |

|||

| Mean rejected |

Difference (accepted–rejected) |

Mean rejected |

Difference (accepted–rejected) |

|

| Panel A. Individual characteristics | ||||

| Year of application | 1,920.81 | 0.87 [0.694] | 1,921.00 | 0.91 [0.779] |

| Year of birth of child | 1,912.05 | 1.397** [0.693] | 1,912.16 | 1.43* [0.766] |

| Child age (years) | 8.74 | −0.508*** [0.124] | 8.827 | −0.519*** [0.155] |

| Day or month of birth missing | 0.02 | 0.014 [0.011] | 0.007 | 0.011* [0.006] |

| Number of children in family | 3.598 | 0.171 [0.133] | 3.538 | 0.193 [0.157] |

| Age of oldest child in family | 11.868 | −0.38 [0.246] | 11.861 | −0.395 [0.261] |

| Age of youngest child in family | 5.623 | −0.799*** [0.170] | 5.63 | −0.775*** [0.187] |

| Length of family name | 6.385 | 0.06 [0.054] | 6.345 | 0.015 [0.078] |

| Widow | 0.512 | 0.023 [0.041] | 0.532 | 0.017 [0.045] |

| Divorced | 0.034 | −0.005 [0.011] | 0.03 | 0.001 [0.014] |

| Husband abandoned/prison/hospital | 0.178 | 0.007 [0.024] | 0.171 | 0.017 [0.025] |

| Mother’s marital status unknown | 0.277 | −0.026 [0.048] | 0.268 | −0.035 [0.056] |

| Predicted family income | 412.528 | −28.335** [13.886] | 423.331 | −36.073 [13.515] |

| Panel B. Age at death and matching | ||||

| Age at death | 72.44 | 0.996* [0.519] | ||

| log age at death | 4.269 | 0.013* [0.008] | ||

| Number of matches | 0.487 | 0.061*** [0.018] | ||

| Quality of merge with DMF file | 1.186 | −0.006 | 1.183 | −0.017 [0.012] |

| Observations | N=16,069 | N=7,860 | ||

| Panel C. Detailed sample sizes | ||||

| Children | 2,177 | 13,892 | 983 | 6,877 |

| Families | 1,346 | 8,104 | 608 | 4,067 |

| Counties | 75 | 75 | 75 | 64 |

| B—Additional Retrospective Data on MP Applicants

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean rejected | Difference (accepted–rejected) |

Observations | |

| Panel A. Ohio | |||

| Probability found | 0.105 | 0.007 [0.021] | 7,456 |

| Share native-born | 0.880 | −0.012 [0.061] | 822 |

| Share homeowner | 0.549 | −0.143 [0.089] | 821 |

| Imputed income (based on occupation) | 531 | −14.04 [35.61] | 811 |

| Panel B. Iowa | |||

| Found in sample | 0.644 | −0.103* [0.0293] | 812 |

| Family income | 721.5 | −33.51 [35.53] | 447 |

| ln(income + 1) | 6.375 | −0.151 | 447 |

| No income | 0 | 0.0325 [0.0188] | 447 |

| Homeowner | 0.383 | −0.233* [0.0686] | 447 |

| Home value (conditional on ownership) | 5,292 | −2,776* | 78 |

| Debt (mortgage/home value) | 0.271 | −0.00789 [0.147] | 76 |

| Paternal education | 6.595 | 1.342* [0.437] | 442 |

| Literate | 1 | −0.0196** [0.00339] | 456 |

Notes: Includes boys ages 0–18, born 1900–1925 in counties with rejected applicants only. We estimate a regression of each characteristic on a dummy for accepted status, clustering the standard errors at the county level. The coefficient and standard error for the constant is reported under “rejected” for each sample.

Interestingly, among accepted children, the exact date of birth of the child is more likely to be missing. We speculate that this could be a potential marker for illiteracy, given that heaping (rounding) in reports of age is correlated with illiteracy (see A’Hearn and Baten 2009 and references therein).23 We test whether these characteristics jointly predict MP receipt, and conditional on receipt, duration or generosity of transfer by regressing an indicator for accepted status on child and family characteristics (Table 1) and find the same patterns.

To assess whether these differences in family characteristics correlate with differences in family income, we estimate the income of accepted and rejected MP applicants based on observable characteristics of the family using the 1915 Iowa census data (prior to the 1940 federal census, the only large-scale survey with information on both income and family characteristics was the 1915 Iowa state census). Specifically, we regress family income on the family characteristics we observe in the MP records (family size, age of all siblings, maternal marital status, length of family name). With these coefficient estimates, we then predict average income (in 1915) for accepted and rejected applicants based on their observable characteristics. We predict that on average accepted applicants had 7–9 percent lower family incomes than rejected applicants. Online Appendix Figure S2d shows the entire distribution of predicted family income. We find that children from accepted families are more likely to have predicted income (based on their characteristics) at or below zero and slightly lower predicted incomes when they are positive. Overall, the evidence shows there are in general small differences between the accepted and the rejected. The few statistically significant differences suggest that the accepted came from slightly worse-off families.

Our second exercise comparing the socioeconomic status of accepted and rejected children, involves matching two subsamples to census manuscripts in the years prior to MP application, allowing us to compare accepted and rejected applicants on pretreatment characteristics in the study including actual, not just predicted income. However, it should be noted that these measures are taken prior to application (when fathers are present) and not at the time of application when fathers are no longer present. As such, they are imperfect measures of family circumstances at the time of application. Despite this, the results of this comparison are still meaningful and suggest that on average, accepted boys come from poorer families.

We first matched Ohio boys to the 1900–1920 federal censuses.24 We were able to match 822 boys from 358 families and found accepted and rejected boys at similar rates: 719 accepted and 99 rejected. We focus on Ohio because it is one of the largest states in our sample (39 percent of the sample) and because we were able to match a larger share to their death records. On average, accepted applicants were less likely to be native-born (87 percent versus 88 percent), less likely to own their home (41 percent versus 54 percent), and had slightly lower incomes imputed based on the occupation of the father ($517 versus $531), though none of the differences reaches statistical significance (Table 2B, panel A). We also present the distribution of imputed income by accepted status in Online Appendix Figure S4 where one observes that the distributions are very similar. These results confirm earlier findings that suggest that the accepted were in fact slightly worse off than the rejected in terms of resources.

We also match MP boys from Iowa to the Iowa 1915 state census which contains measures of family income, homeownership, home value, and paternal educational attainment (panel B of Table 2B). We were able to match 447 children from 257 families. Of those matched, 47 children were from rejected families. Not only is the sample relatively small, but we were unable to find accepted children at the same rate as rejected children, leading to potential selection bias that we believe leads to positive selection of the accepted into this subsample.25 Given this, these results should be interpreted with caution.

Even with these caveats, we still find that compared to rejected applicants, accepted applicants came from poorer families. In particular, accepted families had about 5 percent lower levels of income and substantially lower rates of homeownership (15 percent versus 38 percent). Conditional on homeownership, the homes of the accepted were worth less than half of the value of the homes of the rejected and there is no difference across accepted and rejected in the share of the home value that is mortgaged. We also compare the distributions of income and home value for the accepted and rejected (Online Appendix Figure S4) which appear very similar.

The only pretreatment characteristic on which the rejected appear worse off than the accepted is father’s education. Finding that the accepted are better off on 1 characteristic out of 11 examined might be expected, especially given the small sample size. Upon further inspection, this finding is driven by a handful of rejected fathers with extremely low levels of schooling (Online Appendix Figure S4). A comparison of median schooling shows that accepted and rejected are equivalent (median schooling is 8 for both). Moreover, a number of families are missing paternal education but not income and the missing observations are nonrandomly distributed.26 It is likely that were we not missing paternal education for some of our sample, the difference in average schooling across accepted and rejected would be smaller. In sum, based on our comparison of 11 pretreatment characteristics all of which except for 1 show that the accepted boys came from poorer families, we conclude that the accepted were poorer than the rejected.

Our third piece of evidence comes from the analysis of administrative records showing reasons for rejection or reasons for discontinuance among those accepted. The most common reason for rejection was insufficient need (35 percent). Marriage or remarriage is a common reason for rejection (8 percent), whereas ineligibility due to insufficient length of residency and noncitizenship appear to be very uncommon (Table 3). In Clay County, MN, where we have detailed information for all families, the most commonly reported reason for discontinuation of a pension was that the family was judged to be capable of self-support. Abbott and Beckenridge (1921) also report that in Cook County 60 percent (293 out of 532) of the rejected applicants were denied because of sufficient funds.

Table 3.

Reasons for Rejection Distribution in All Records and in Estimation Sample (Percent)

|

Panel A. All records

|

Panel B. Boys in sample

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reason MP denied |

Reason MP ended |

Reason MP denied |

Reason MP ended |

|

| Other means | 35.26 | 17.38 | 37.42 | 20.01 |

| Ineligible | ||||

| Ineligible, reason unspecified | 29.53 | 43.13 | 19.24 | 39.97 |

| Married or husband returns | 7.95 | 27.25 | 6.97 | 25.34 |

| Moved from county | 3.58 | 6.52 | ||

| No children eligible | 2.03 | 2.12 | ||

| Doesn’t meet residency requirement | 1.36 | 2.73 | ||

| Not a citizen | 0.32 | 0.76 | ||

| Other reasons | ||||

| Withdrew | 8.29 | 3.64 | ||

| Application incomplete | 4.09 | 6.97 | ||

| Immoral/unft | 3.80 | 3.22 | 4.24 | 4.39 |

| Not dependent for long enough | 1.93 | 5.61 | ||

| Mother lied in application | 0.51 | 1.36 | ||

| Child delinquent | 1.62 | |||

| Divorced | 0.70 | 1.06 | ||

| Mother died/hospitalized/in prison | 0.64 | 4.23 | 1.36 | 4.11 |

| Observations with data | 3,738 | 13,794 | 660 | 4,692 |

All three exercises support our assumption that differences between the groups are on average small and insignificant, or that the accepted are somewhat poorer. Given these results we proceed to look at whether the program impacted outcomes, under the assumption that mean comparisons between these groups will yield a lower bound on the effect of the program.

IV. Mortality Results

A. Preliminary Evidence

Accepted boys lived on average to age 72.4, nearly one year longer than rejected boys (Table 2A). Examining the full distribution of longevity, we observe that the distribution of the age at death of accepted applicants is shifted to the right of the distribution of rejected applicants (Figure 1). The distributions are statistically different at the five percent level. The largest differences are observed between ages 60 and 80, where the distributions are the densest.27

Figure 1.

Distribution of Age at Death

Notes: Figure based on matched sample of boys of accepted and rejected applicants. We reject the null that the distributions are the same using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. This figure includes only those with unique matches to age certificates. Deaths below 20 dropped.

B. Main Results

Panel A of Table 4 shows the estimates for longevity estimated using the AFT hazard model in (1) based on the sample of individuals with a unique age at death. In column 1, we include only state and cohort dummies. In column 2, we add all individual controls, county characteristics in 1910 and state characteristics at the time of application. In column 3, we add county fixed effects. The results are not very sensitive to the inclusion of covariates. In column 4 we use the date of birth from the death certificate instead of the date on the MP application. The coefficient on acceptance is positive in all specifications and the implied effects are large: acceptance increased life expectancy by about a year, relative to a mean of 72.5, among the rejected. The estimates range from 1.1 to 1.3 years of life depending on the specification and sample.

Table 4.

Cash Transfers and Long-Term Mortality

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. log age at death | |||||

| Accepted | 0.0157** [0.006] | 0.0158** [0.007] | 0.0182** [0.007] | 0.0167** [0.007] | |

| Mean of rejected | 72.44 | 72.44 | 72.44 | 72.44 | |

| Effect in years | 1.14 | 1.16 | 1.32 | 1.2 | |

| Observations | 7,860 | 7,860 | 7,860 | 7,860 | |

| Panel B. Survival estimation P(survived past 60) Accepted | 0.193*** [0.048] | 0.121** [0.049] | 0.108** [0.052] | 0.103** [0.052] | 0.0377 [0.144] |

| Mean of rejected | 0.421 | 0.421 | 0.421 | 0.421 | 0.880 |

| Percent effect | 11 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| P(survived past 70) Accepted Mean of rejected | 0.265*** [0.052] 0.287 | 0.205*** [0.053] 0.287 | 0.211*** [0.056] 0.287 | 0.199*** [0.056] 0.287 | 0.267*** [0.071] 0.596 |

| Percent effect | 19 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 11 |

| P(survived past age 80) Accepted | 0.239*** [0.067] | 0.195*** [0.068] | 0.187*** [0.071] | 0.192*** [0.071] | 0.164* [0.097] |

| Mean of rejected | 0.146 | 0.146 | 0.146 | 0.146 | 0.305 |

| Percent effect | 20 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 11 |

| Observations | 16,069 | 16,069 | 16,069 | 16,069 | 7,858 |

| State fixed effects | X | ||||

| Cohort fixed effects | X | X | X | X | X |

| Individual controls | X | X | X | X | |

| State characteristics | X | X | X | X | |

| County 1910 characteristics | X | ||||

| County fixed effects | X | X | X | ||

Notes: Standard errors (in brackets) are clustered at the county level. For panel B, logit coefficients reported. Percent effects computed relative to the average for rejected boys. Individual controls include child age at application, age of oldest and youngest in family, dummies for the number of siblings, number of letters in name, a dummy for whether date of birth is incomplete, year of application, and dummies for the marital status of the mother. County controls for 1910 include all characteristics listed in Table S6. State characteristics at the time of application include manufacturing wages, education/labor laws (age must enter school, age can obtain a work permit, and whether a continuation school law is in place), state expenditures in logs (education, charity, and total expenditures on social programs), and state laws concerning MP transfers (work required, reapplication required, the maximum legislated amount for the first child, and the legislated amount for each additional child).

significant at the 1 percent level.

significant at the 5 percent level.

significant at the 10 percent level.

To assess the role of attrition in this finding, we present estimates of the effect of the MP program on the probability of survival past ages 60, 70, and 80 (panel B of Table 4), by first assuming those without a match died prior to age 60 (columns 1–4), and then by dropping all unmatched records (column 5). We find statistically significant increases in the probability of survival past age 70 (ranging from 10 to 20 percent), and the probability of survival past age 80 (of about 9 to 15 percent). The results for survival past 60 are entirely driven by our assumption regarding attrition, whereas the results for ages 70 and 80 are not. These results are very similar if we use the date of birth from the death certificate instead of the one from the MP records (column 4), or limit the analysis to unique matches only (column 5).28

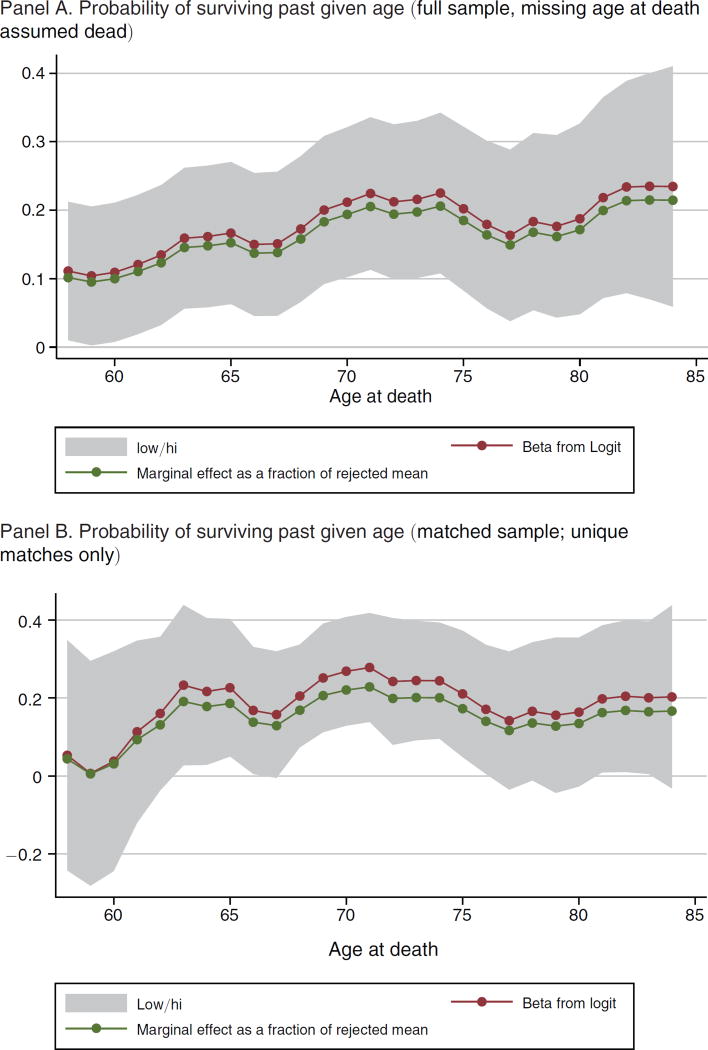

Next, we abandon the arbitrarily chosen cut-offs of ages 60, 70, and 80 and estimate our survival model using the fully saturated specification for each age at death between 58 and 88, which correspond to the tenth and ninetieth percentiles of the distribution of the age at death. Figure 2 shows the marginal effects as a percentage of the survival rate of rejected applicants, computed using coefficients from estimation with (top panel) and without (bottom panel) imputing the missing observations as zeros. All coefficients are positive and significant after age 67, regardless of whether we impute missing values as 0 or not. Joint tests of statistical significance show that we cannot reject the null that all coefficients are positive.

Figure 2.

Effects by Age

Notes: The coefficients are jointly significantly different from zero (p > 0.001). All specifications use the full set of controls as in column 4 of Table 4.

C. Heterogeneity by Income and Urban Residence

In this section we explore heterogeneous effects of the MP program by family income, age of the child, and urban residence. Though we do not observe family income, we are able to predict family income for observations in all the states in our data based on observable demographic characteristics of the families and the estimated relationship between those characteristics and family income in the 1915 Iowa census.29 After predicting income, we split the sample into low income (below median predicted income) and high income (above median predicted income) and compare accepted and rejected within these two broad income groups. In so doing, we further limit our comparison to accepted and rejected applicants who appear most similar in terms of resources (income) available to them. We also confirm that when we stratify the sample in this way, that the accepted and rejected within these subsamples are still similar on observables (Online Appendix Table S7c).

The effect of the MP program appears to be larger among the poorest in the sample (Figure 3).30 For those predicted to have income below the median, acceptance increases longevity by 1.44 years, which is 15 percent higher than the effect for those above the median income, though the difference across the two subgroups is not statistically significant (Table 5).31 Also note that the average age at death is higher for the sample with higher predicted family income in childhood, which suggests that our predicted income is indeed correctly classifying individuals into income categories, since family income is a well-known predictor of mortality.

Figure 3.

Estimates by Predicted Family Income and Urbanicity (Unique Matches Only)

Table 5.

Heterogeneity and Robustness Checks

| Stratified sample | coefficient on accepted |

N | Mean of rejected applicants |

Effect of acceptance in years |

p-value for test of equality across groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Subgroup analysis | |||||

| Income above median | 0.0171* [0.009] | 3,944 | 72.78 | 1.24 | |

| Income below median | 0.0200* [0.012] | 3,915 | 72.02 | 1.44 | 0.84 |

| Fraction urban above median | 0.0225* [0.012] | 4,282 | 72.04 | 1.62 | |

| Fraction urban below median | 0.0162** [0.007] | 3,577 | 72.87 | 1.18 | 0.64 |

| Fraction foreign born above median | 0.0176** [0.008] | 3,729 | 72.98 | 1.28 | |

| Fraction foreign born below median | 0.0185 [0.012] | 4,130 | 72.02 | 1.33 | 0.95 |

| Panel B. Additional robustness checks | |||||

| Full sample | 0.0182** [0.007] | 7,860 | 72.44 | 1.32 | |

| Age <= 14 | 0.0201*** [0.006] | 7,408 | 72.32 | 1.45 | 0.25 |

| Age <= 10 | 0.0173** [0.008] | 5,202 | 72.32 | 1.25 | 0.86 |

| Born 1900–1920 | 0.0219** [0.008] | 6,798 | 72.32 | 1.53 | 0.12 |

| Born 1900–1910 | 0.0211** [0.010] | 2,524 | 72.32 | 1.53 | 0.69 |

| Born 1911–1920 | 0.0189 [0.012] | 4,274 | 72.32 | 1.37 | 0.92 |

| Family size between 3 and 7 | 0.0244** [0.009] | 5,178 | 72.32 | 1.76 | 0.22 |

Notes: Table shows effect of “accepted” on log (age at death) for selected subsamples. Standard errors (in brackets) are clustered at the county level. Effects computed relative to the average for rejected boys. All coefficients are estimated from separate regressions, with standard errors clustered at the county level and include all controls: individual characteristics (age at application, age of oldest and youngest in family, dummies for number of siblings, number of letters in name, a dummy for whether date of birth is incomplete, year of application, and dummies for the marital status of the mother); state characteristics at the time of application include manufacturing wages, education/labor laws (age must enter school, age can obtain a work permit, and whether a continuation school law is in place), state expenditures in logs (education, charity, and total expenditures on social programs), and state laws concerning MP transfers (work required, reapplication required, the maximum legislated amount for the first child, and the legislated amount for each additional child); county dummies and cohort dummies.

significant at the 1 percent level.

significant at the 5 percent level.

significant at the 10 percent level.

Existing work on the importance of conditions in early childhood in determining later long-term outcomes (Almond and Currie 2011a) suggests that the effects of the MP program might decrease in the child’s age. We split our sample into 3 groups by age of the child at the time of application: children younger than 5, children aged 5–9, and children aged 10–14. We find slightly larger, though not statistically significantly so, effects for younger children: children under 10 are 17–18 percent more likely to survive past age 70 than their rejected counterparts, relative to 11 percent for children aged 10–14.

A criticism of the MP program was its reliance on counties as the main administrative unit. This resulted in wide variance across counties in the implementation of the program. In particular, the historical record suggests that rural and urban counties implemented the programs differently.32 When we split the sample into counties above and below the median share urban, we find no significant differences in the magnitudes: the effects are positive and similar in magnitude in both samples (Figure 3 and Table 5).

D. Discrimination and the Composition of Rejected Applicants

If rejected mothers were subject to discrimination on the basis of unobservable characteristics that are negatively correlated with child outcomes, this could threaten our identification strategy. We consider the two most likely sources of discrimination: race and nativity. With respect to discrimination on the basis of race, in a 1931 survey and analysis of the MP program, the US Department of Labor determined that 96 percent of MP recipients were white despite the fact that black mothers were at least as likely to be in need, consistent with other accounts (Goodwin 1992 and citations therein, Ward 2005). To address this, we link a subset of the MP records to WWII enlistment data and 1940 census data that contain race (Tables 6 and 7). This is necessary because MP records do not report the race of applicants. We find that blacks are not more likely to have been rejected. We also present results for Ohio where the Department of Labor reported a lack of discrimination against black mothers in its 1931 report. The results are unchanged when we limit the analysis to the Ohio sample (Online Appendix Table S7a).

Table 6.

The MP Program and Medium-Term Outcomes from the 1940 Census

| No controls |

All controls |

Observations | Mean rejected |

Percent effect |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual income in 1939 | 76.06 [54.222] | 90.93** [35.976] | 1,960 | 666.2 | 13 |

| Years of schooling | 0.431* [0.230] | 0.316 [0.262] | 2,058 | 9.363 | 4 |

| Black = 1 | 0.00440 [0.007] | 0.00607 [0.007] | 2,099 | 0.008 | 40 |

Notes: Standard errors (in brackets) are clustered at the county level. Effects computed relative to the average for rejected boys. All coefficients are estimated from separate regressions, with standard errors clustered at the county level and include all controls: individual characteristics (age at application, age of oldest and youngest in family, dummies for number of siblings, number of letters in name, a dummy for whether date of birth is incomplete, year of application, and dummies for the marital status of the mother); state characteristics at the time of application include manufacturing wages, education/labor laws (age must enter school, age can obtain a work permit, and whether a continuation school law is in place), state expenditures in logs (education, charity, and total expenditures on social programs), and state laws concerning MP transfers (work required, reapplication required, the maximum legislated amount for the first child, and the legislated amount for each additional child); county dummies and cohort dummies.

significant at the 1 percent level.

significant at the 5 percent level.

significant at the 10 percent level.

Table 7.

The MP Program and Medium-Term Outcomes from WWII Records

| Models | No controls |

All controls |

Observations | Mean rejected |

Percent effect |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Education | ||||||

| Has exactly eight years of school | Logit | −0.326** [0.137] | −0.206 [0.170] | 2,446 | 0.33 | 20 |

| Education: left and right censored | Censored regression | 0.348* [0.197] | 0.249 [0.201] | 2,446 | 10.38 | 2 |

| Panel B. Anthropometrics Height (cms) | OLS | 1.346 [0.827] | 1.142 [1.248] | 1,844 | 174.5 | 1 |

| Weight (pounds) | OLS | 3.879* [1.955] | 3.417* [1.984] | 1,817 | 144.7 | 2 |

| BMI | OLS | 0.537** [0.215] | 0.464* [0.239] | 1,706 | 22.06 | 2 |

| Underweight | Logit | −0.690** [0.298] | −0.638 [0.411] | 1,706 | 0.09 | 58 |

| Obese | Logit | 0.416 [0.496] | 0.998 [0.751] | 1,706 | 0.03 | 98 |

| Panel C. Race Black = 1 | Logit | 0.282 [0.289] | 0.0284 [0.274] | 1,691 | 0.038 | 3 |

Notes: Standard errors (in brackets) are clustered at the county level. Model in column 2 is estimated using county and cohort fixed effects and include individual characteristics at the time of application. State characteristics at the time of application include manufacturing wages, education/labor laws (age must enter school, age can obtain a work permit, and whether a continuation school law is in place), state expenditures in logs (education, charity and total expenditures on social programs), and state laws concerning MP transfers (work required, reapplication required, the maximum legislated amount for the first child, and the legislated amount for each additional child).

significant at the 1 percent level.

significant at the 5 percent level.

significant at the 10 percent level

Similarly, discrimination against immigrants could result in their disproportionate representation among rejected applicants, threatening identification and biasing our results in favor of estimating positive effects of the MP program. The historical record on this, however, is more mixed with some reports of discrimination against mothers on the basis of nativity and other reports of no discrimination.33 We present two pieces of evidence suggesting that discrimination on the basis of nativity is not biasing our results. First, in the subsample in which we matched individuals to pre-application censuses, we find that in fact immigrants were not less likely to receive pensions (Table 2B). We also split the sample by fraction foreign born in the county and find similar effects of MP receipt on age at death in samples with a high and low fraction of immigrants (Table 5). As a final effort to control for underlying differences between the accepted and rejects, we match accepted and rejected on propensity scores. The results are unchanged (Online Appendix Table S7a).

We consider additional sources of differences between accepted and rejected mothers: age of the child (older children more likely to be rejected) and number of children (very small and very large families more likely to be rejected). When we drop individuals over the age of 14 (the maximum age in most states) or over age 10, our results are unaffected (Table 5).34 Likewise, if we drop boys from extremely small or large families, we obtain similar estimates. Finally, we reestimate the model dropping individuals born after 1920, since the life table calculations suggest a nontrivial portion of them might still be alive in 2012. This makes no difference. The estimates are very similar when we look at the early cohorts (1900–1910) or later cohorts (1911–1920).

E. Aggregate Results

We estimate models with data aggregated at the level of the county, year of application, and year of birth. In these models, we regress the fraction surviving past age 70 (or the average age at death) on the fraction accepted. Whether we use weights or include controls, we find positive effects. These effects (Online Appendix Table S7b) are similar in magnitude to those we estimate using the individual data: between a 13 and a 25 percent increase in survival past age 70 or about 1. 2–1.9 additional years of life. These results rule out the possibility that counties with high rejection rates are driving the results.

F. Results for Ohio

We present separate estimates for the state of Ohio—the state from which 34 percent of individuals in our sample originate—for several reasons. First, Ohio and Pennsylvania were the only two states where black mothers appear to have received MP benefits at expected rates given their share in the population (as identified by the Children’s Bureau in their 1933 report), which makes it unlikely that discrimination against blacks is driving our results. Second, the same Children’s Bureau report (1933) indicates that applicants from Ohio were not required to be US citizens, which suggests that Ohio lawmakers were not advocating the exclusion of immigrants from the MP program. Lastly, we collected county-level expenditures on social programs over time from the Ohio General Statistics (available for 1915–1922) to control for other sources of support at the time of application, so as to rule out the possibility that higher rejection rates maybe correlated with a greater safety net, potentially biasing our estimates.

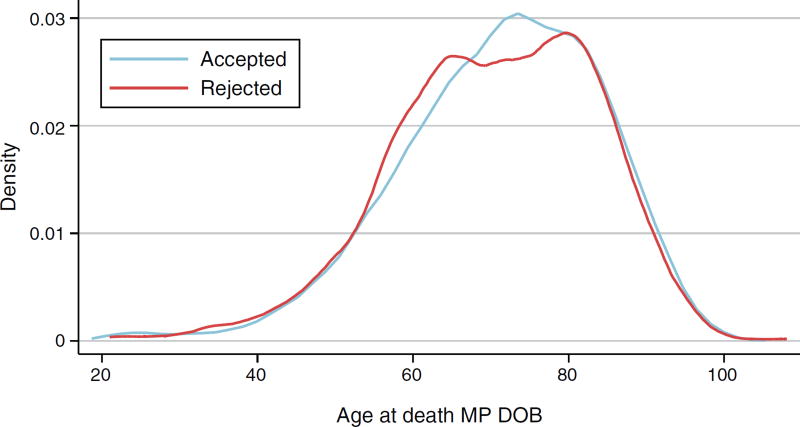

Figure 4, which depicts the densities of the age at death, shows that in Ohio, rejected boys lived shorter lives than accepted boys. The estimates in Online Appendix Table S7a, with and without controls, show that the longevity effects are essentially unchanged, though perhaps slightly larger for the Ohio sample. This suggests that neither discrimination against blacks and nonnative mothers nor the availability of other social programs are biasing the results.

Figure 4.

Ohio, Matching to Additional Death Records

Notes: Records matched first to Death Mortality Files (DMF) and then to Ohio state death records that go back to 1958. Remaining unmatched records were then manually imputed by searching individual records in Ancestry.com. Unique matches only.

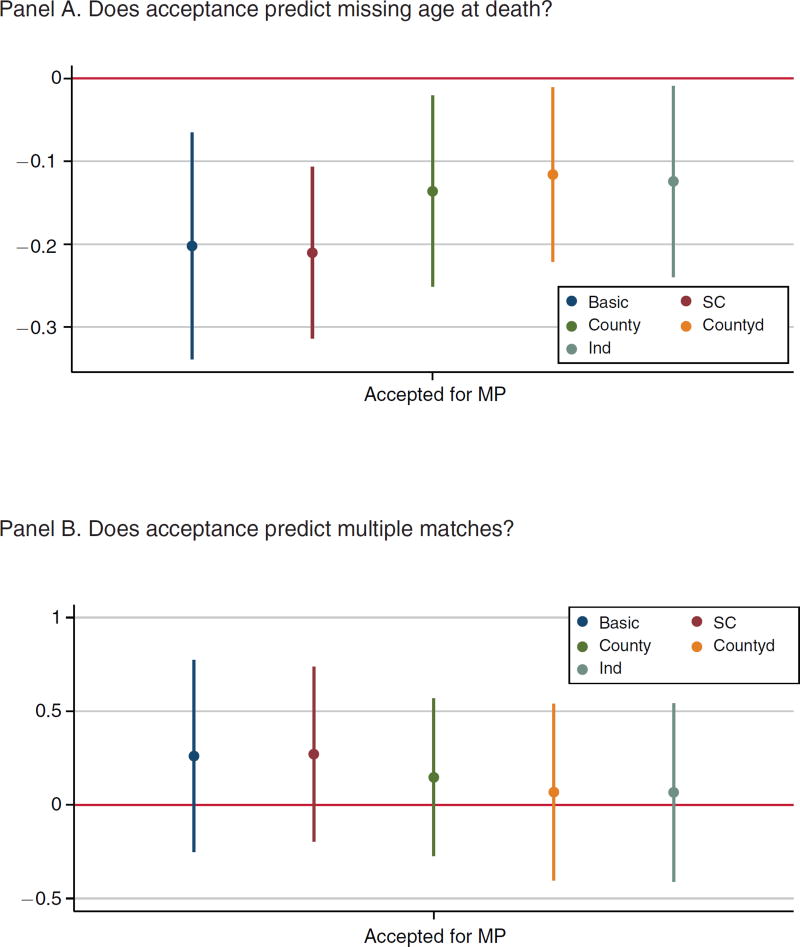

G. Attrition and Multiple Matches

We are more likely to match accepted applicants to their death certificates (55 percent) than we are to match rejected applicants (49 percent). This 10 percent differential matching rate (Table 2A) is not eliminated when we control for observable characteristics (Figure 5). This difference in the match rate is consistent with the MP program improving health and lowering mortality at all ages. Alternatively, if rejected boys have a lower match rate for other reasons, this could bias our estimates.

Figure 5.

Differential Attrition and Matching

Notes: coefficient from logit on Accepted = 1. Graphs display coefficients and 95 percent confidence intervals.

We present several pieces of evidence that support differential attrition due to mortality rather than other factors. Based on the life tables for the 1910 birth cohort in the United States, we compute that a 10 percent reduction in adult mortality from age 40 onward for the 1910 cohort is equivalent to an increase in longevity of approximately 0.9 years. Thus, the magnitude of the attrition is consistent with the magnitude of the mortality declines we estimate. In addition, when we matched applicants to retrospective pre-application records (as in Table 2B), we find that the match rates of both the accepted and rejected applicants are the same, which rules out the concern that differences in the names across the two groups cause the differential matching. Lastly, when we find more than one possible match, we do so at identical rates across accepted and rejected applicants (Figure 5), which is consistent with mortality, rather than other factors, affecting attrition rates.

For the state of Ohio we collected additional data on deaths prior to 1975, by matching MP records with the state death records that date back to 1958, and by manually searching for death certificates for unmatched children of Ohio MP applicants on Ancestry.com. In so doing, we increased our match rate to 60 percent.35 When we add these additional matches (Online Appendix Table S7a, panel D), our results remain unchanged. Among the newly matched, the mortality differential between accepted and rejected is again about one year (66.3 versus 67.2 age at death), which is exactly what we estimate using the original data. For this newly matched sample, we continue to find death records for accepted applicants at higher rates. Even when we push mortality comparisons back to 1958, the rejected die younger than the accepted, which suggests that our inability to link rejected MP applicants to death records prior to the mid-1970s is in fact related to their higher mortality.

This newly matched sample also sheds light on why our results are small and imprecise when the dependent variable is the probability of survival to age 60. Approximately 60 percent of the newly found death records show that children of MP recipients did not survive to age 70, but only about 30 percent of children died before age 60. We conclude that the assumption that the missing are dead is reasonable for specifications in which the dependent variable is the probability of survival past 70 but not when it is survival to ages younger than 70.

Finally, we consider cases of multiple matches which represent 4 percent of our sample. The results are similar when we estimate standard logit models using unique matches, or when we use the maximum likelihood methods developed in Bugni, Honoré, and Lleras-Muney (2014) to include multiple matches. The results are also not sensitive to the exclusion of observations with more than three matches, or choosing the highest quality match for those with multiple matches (online Appendix II). Although the coefficients differ in magnitude when we change the sample, the marginal effects remain similar across all specifications (Online Appendix Table S7a).

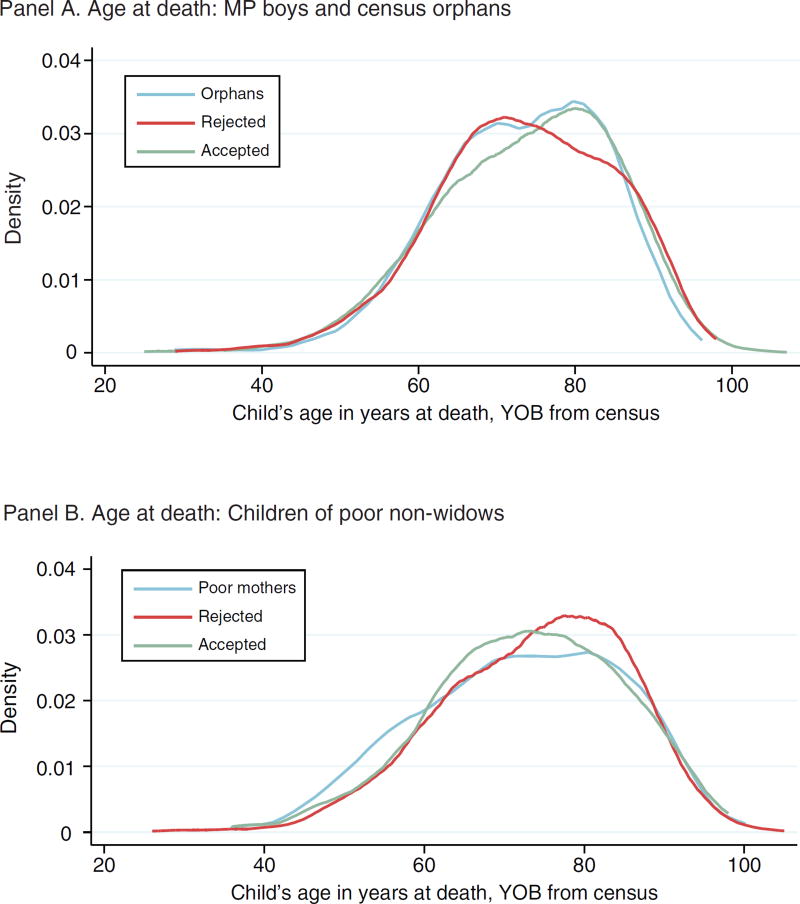

H. Alternative Counterfactuals From the 1900–1930 Censuses

For comparison, we constructed two alternative “control” groups from the 1900, 1910, 1920, and 1930 censuses and matched them with their death records in the DMF (see online Appendix III for details).36 The first alternative counterfactual group is orphans, who are identified as children living in institutions in the census. Since MP programs were developed in large part to prevent the institutionalization of children in orphanages and instead allow children to remain at home with their mothers, orphans represent an appropriate historical counterfactual. We find that the orphans are very similar to the rejected applicants with regard to longevity, with both living shorter lives than accepted applicants (Figure 6, panel A).

Figure 6.

Alternative Counterfactuals

Notes: Panel A: Unique matches only. Orphans defined as children living in institutions. Panel B: From ln states where divorced/abandoned mothers are ineligible: unique matches only. We exclude CO, MN, OH, and WI.

The second counterfactual group is comprised of children of single or divorced women, who were drawn from the census records in states where these women were not eligible for the MP program. We compare children of this group of ineligible women to accepted MP children whose fathers were disabled or institutionalized (but not to children of widows) because, on observables, these children appear similar.37 We find that children of accepted women lived longer than this alternative control group of ineligible children of single and divorced women (Figure 6, panel B).

V. Results for Educational Attainment, Health, and Income in the Medium-Term

To understand the ways in which income transfers in childhood improved longevity, we explore potential mechanisms. Previous work has shown education, income, and weight (being underweight, in particular) are strongly associated with mortality (Flegal et al. 2005; Deaton and Paxson 2001; Cutler and Lleras-Muney 2008). In this section we estimate the effect of the MP program on these possible medium-term (adulthood) outcomes by linking the MP sample to 1940 census and WWII enlistment records.

A. 1940 Census Records

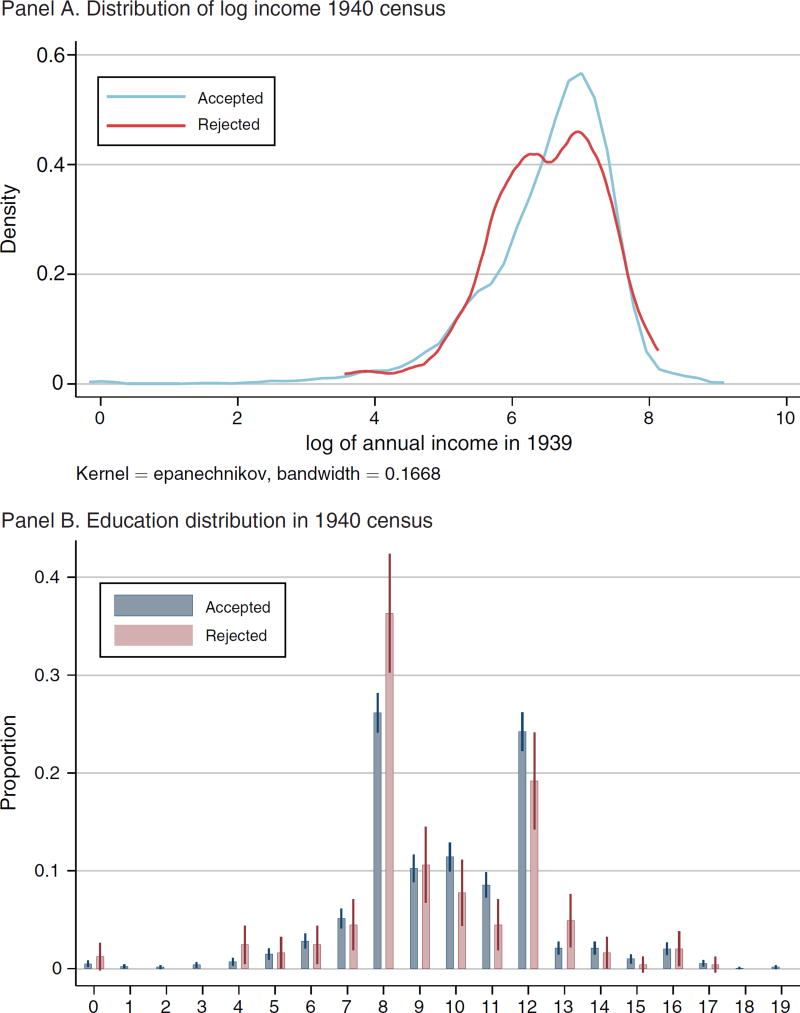

Matching MP applicants to 1940 census data allows us to examine the impact of MP receipt on educational attainment and income during young adulthood. Rejected boys are much more likely to have not started high school and accepted boys are more likely to have graduated high school (Figure 7, panel A). Results from regression analysis with full sets of controls shows that MP receipt results in between 0.3 and 0.4 more years of schooling, though we lose precision when we add the full set of controls.

Figure 7.

Effect of MP on Outcomes from 1949 Census Records

With respect to income, we observe that the distribution of log income is shifted to the right for accepted boys (Figure 7, panel B). Results from a regression with full controls show that MP recipients on average have incomes that are 14 percent higher than their rejected counterparts in 1940 (Table 6). Online Appendix Figure S5 shows that MP receipt is associated with a positive increase in the chance of being in the twenty-fifth, fiftieth, or seventy-fifth percentile of the distribution in the sample, but most of these estimates are not statistically significant.

B. World War II Enlistment Records

We can match individuals in the MP records to their WWII enlistment records for the cohort that enlisted in the Army during 1938–1946.38 For all enlistees, we observe educational attainment as well as two anthropometric measures (weight and height), which are markers of nutritional deprivation in childhood. Adult height, in particular, has been linked with childhood nutrition, as well as adult cognitive ability and labor market outcomes (Case and Paxson 2008).

The WWII results should be viewed as suggestive, rather than definitive, for two reasons. First, our match rate is low (17.2 percent of males overall, 32.9 percent for those born 1919–1925), lower than our match rate for mortality. This is because WWII records do not contain exact date-of-birth. They do however contain state-of-birth, which we add to our matching criteria. Second, the WWII records are a selected subset of the male population because of induction rules and exemptions. As a result, our matched sample is younger given that males aged 18–25 in 1942 served at much higher rates than older men (Hogan 1981), healthier given the mental and physical requirements for enlistment, and more highly educated given minimum schooling requirements for enlistment of 8 years.39

We estimate the effect of MP transfers on the fraction with more than eight years of school (Figure 7), or using a censored regression for years of schooling (Table 7). We find that children of accepted families are 20 percent more likely to have more than eight years of school (Table 7, column 1 without controls and column 2 with controls). When we estimate a censored model that accounts for the two sources of censoring, we find that MP recipients complete a third of a year more school than rejected applicants, and the effect is marginally significant. When we include the full set of controls, the point estimates remain similar, but are no longer precisely estimated. These results are very similar to the results from the 1940 census records (Table 6).

MP receipt also significantly reduces the probability of being underweight (Figure 8). Recall that in the detailed MP records from Clay County, MN, nurses noted malnutrition as one of the most commonly observed health problems during visits to families in the MP program. Estimates in Table 7 imply a statistically significant 50 percent reduction in the probability of being underweight, with similar results but less precision with the full set of controls. The estimates for height, weight and BMI (measured continuously) are also positive and significant for weight and BMI. Our results showing greater impact of MP receipt at the lower tail of the distribution of weight are consistent with our earlier finding that the effects of cash transfers on mortality were greatest among the most disadvantaged families. We conclude that the transfers helped families improve the nutrition of their children, particularly for those at greatest risk of malnutrition.

Figure 8.

Effect of MP on Outcomes from WWII Records

Note: Panel B: Graph from unique matches only.

C. Magnitudes

We find that receipt of MP transfers resulted in a significant 50 percent decrease in under-nutrition, a 13 percent increase in income, and an increase of 0.4 years of school among young adults. Would these effects result in the longevity gains that we estimate? Being underweight in adulthood is associated with a relative risk of mortality that ranges from 1.38 to 2.3 (Flegal et al. 2005). This is a large effect but since only 10 percent of our sample is underweight, the expected increase in longevity through this channel would be small. However, income and education likely play a larger role in explaining our mortality results. Based on Deaton and Paxson’s (2001) estimate of the long-term elasticity of mortality with respect to income (−0.3 to −0.6), a 30 percent increase in income would lower mortality by at least 10 percent, increasing longevity by 0.9 years.40 Cutler and Lleras-Muney (2008) report that an increase in schooling of 0.25 years is associated with a 0.15 year increase in longevity in OLS regressions. We conclude that the estimated effects of the MP transfer on education and income would imply at least one additional year of longevity, which is consistent with our estimated effects on longevity (1.1–1.4 years). These two mechanisms alone explain 75–95 percent of the increase in life expectancy associated with MP transfers.

Our mortality results are also consistent with the estimated short-run effects of other cash programs on mortality. Conditional cash transfers in Mexico, which are estimated to account for about 30 percent of pre-transfer income, decrease short-run mortality by about 4 percent for the elderly, and by about 17 percent among infants, with effects up to 30 percent for the poorest families (Barham 2011; Barham and Rowberry 2013). A decrease in mortality of 5 (10) percent throughout the lifetime would increase life expectancy for the 1910 cohort by about 0.5 (1) years. Thus our results are consistent with a 10 percent decline in adult mortality resulting from a 20–30 percent increase in childhood income.

The estimated effects of income may be underestimated. In a period of high infectious disease, such as the early twentieth century, improvements in nutrition are likely to lower the spread of disease; if this is the case, the rejected children might have benefited from the transfers leading us to understate the total (i.e., to society) benefits of the transfers. Indeed Fishback, Haines, and Kantor (2007) show relief monies during the 1930s lowered infant mortality for all children. This seems unlikely in our case because the MP program covered a very small share of the poor, so spillovers would be minimal.

We could also be overestimating the increase in income associated with the transfers. For instance, if rejected families get other relief, then we overestimate the increase in income and understate the effects of income. The availability of non-MP benefits and their provision to rejected MP applicants would narrow the “true” gap between resources available in rejected and accepted households. If we observe an effect size of X per unit of MP but each unit of MP provided resulted in a resource differential of only αX (α < 1), then the “true” effect of MP in the absence of other benefits available to rejected families would, to a first approximation, be X/α. There is scant evidence on this, but for example Abbott and Beckenridge (1921) report that families who were dropped from the MP program in Cook County in 1913 subsequently received charity in a smaller amount.41