Abstract

Background

Head-shaking stereotypies have been described in patients with neurological impairment. We noted an unusual preponderance of head shaking in patients with rhombencephalosynapsis (RES). We sought to delineate the movements further and determine whether oculomotor and vestibular testing could reveal their cause.

Methods

Information was collected from direct observation, video review and parental questionnaire from 59 patients with RES. Oculomotor and vestibular testing was performed in 4 children.

Results

50 of 59 patients had persistent head shaking that was often observed years before RES was recognized. Three affected children demonstrated abnormal central vestibular processing.

Conclusions

Head-shaking is common in RES. These characteristic movements may provide input to a defective vestibular system or may represent a motor pattern that is usually suppressed by vestibular feedback. Persistent head shaking should alert clinicians to the possible presence of a congenital hindbrain abnormality that affects the vestibulocerebellum, particularly RES.

Keywords: stereotypy, bobble head doll syndrome, rhombencephalosynapsis, movement disorder, vestibular dysfunction

Introduction

Stereotyped head movements have been described in association with various neurological conditions, as well as in normal children. The origin of these movements is unknown. We noted an unusual preponderance of distinctive head-shaking movements in a cohort of patients with rhombencephalosynapsis (RES), an under-diagnosed brain malformation characterized by partial or complete absence of the cerebellar vermis with continuity of the cerebellar hemispheres across the midline1 (figure 1). We hypothesized that persistent head shaking could provide an important diagnostic clue to the presence of RES. We also reasoned that this group of patients might give insight into the pathobiology of head-shaking stereotypies in general. We therefore sought to characterize these movements further and determine whether behavioral observation in conjunction with oculomotor and vestibular testing could provide clues to their origin.

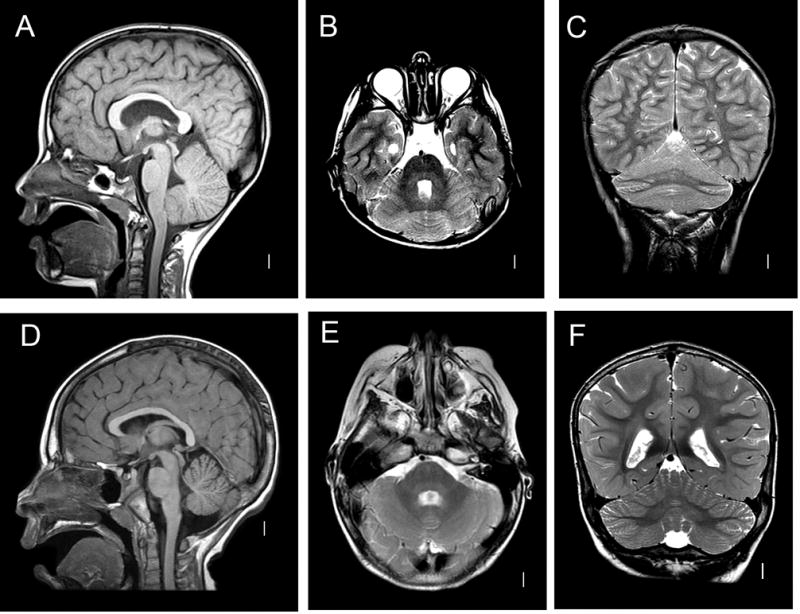

Figure 1. MRI Features of RES.

A–C: RES. Midline sagittal T1-weighted image demonstrates hemispheric rather than vermian lobulation pattern of the cerebellum (A). Axial T2-weighted image shows fusion of cerebellar white matter across the midline and a keyhole-shaped 4th ventricle (B). Coronal T2 demonstrates continuity of cerebellar folia across the midline without an intervening vermis (C). D–F: Normal brain.

Methods

Patient acquisition

Patients with RES had previously been ascertained from brain malformations registries maintained by two of the authors (Doherty, Dobyns).

Assessment of stereotypies and related conditions

We collected information about head movements through direct observation, review of video supplied by parents and referring clinicians, and parental survey. We also collected information about age of onset, exacerbating and ameliorating factors, additional stereotypies and tics, as well as clinical features suggestive of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

Degree of rhombencephalosynapsis

Degree of rhombencephalosynapsis was assessed by a pediatric neuroradiologist (Ishak), a developmental pediatrician specializing in hindbrain malformations (Doherty), and a pediatric neurologist (Tully). A severity score from 1–4 was assigned based on the structures involved (1: anterior and posterior vermis and nodulus at least partially present, 2: absent posterior vermis, 3: absent anterior and posterior vermis, 4: absent anterior and posterior vermis and nodulus) as previously described1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad QuickCalcs online software (www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/).

Oculomotor and vestibular testing

Oculomotor and vestibular testing was performed in a dedicated laboratory by a vestibular neurophysiologist (Phillips) and a pediatric ophthalmologist (Weiss). Oculomotor performance was assessed with binocular video oculography (SMI 2D VOG) in the dark, and in response to moving and stationary point targets as well as a moving full-field optokinetic stimulus (0.10 cycles/degree, 100% contrast square wave grating.) Vestibular testing was performed on a rotatory chair with eye movements recorded with monocular video-oculography (Micromedical Technologies System 2000). Multiple tests were performed in each child, including sinusoidal rotation (0.01–0.64Hz, 60 degrees/second peak velocity), constant velocity step rotation (100 degrees/second velocity, 45 second duration, 1000 degrees/second/second step), fixation suppression of sinusoidal VOR with a point target and visual enhancement of sinusoidal VOR in the light (both 0.5Hz, 60 degrees/second peak velocity). Gain, phase and symmetry of sinusoidal VOR in the dark, during suppression, and during visual enhancement were calculated using Fourier transformation of the recorded eye position and chair velocity data. Gain and time constants were calculated for step velocity testing, the latter with an exponential fit to the per-rotary and post-rotary nystagmus elicited by each step.

Results

We obtained information about motor stereotypies and related symptoms in 59 patients with RES who ranged in age from 6 months to 32 years (mean 7.8 years, SD 7.6 years). 34 were male and 25 female. 50 patients (85%) had striking head-shaking movements characterized by a rhythmic, repetitive figure-8 or occasionally side-to-side swinging motion that was intermittent in some individuals and near-constant in others (Videos 1,2,3,4,5). The movements occurred most frequently during times of fatigue, excitement, and reduced visual attentiveness. The movements abated with visual fixation, tactile stimulation of the face and during sleep.

Of the 34 patients whose parents could estimate time of onset, 22 (65%) developed head shaking during their first year of life, 6 (18%) in their second year, and 6 (18%) at age 2 years or older. In 31 of 39 patients (79%), head shaking was observed before the underlying cerebellar malformation was recognized, with a time to diagnosis that ranged from a few months to 32 years. The mean RES severity score was 2.34 (SD = 1.0) for head-shakers and 2.25 (SD = 1.2) for non-head-shakers (p = 0.8, NS).

Additional stereotypies were noted in 28 of 36 patients (78%), including repetitive hand movements such as clapping, rubbing or wrist rolling (n=13), arm flapping (n=9), teeth grinding (n=4), body rocking (n=2) and head banging (n=2). Motor and phonic tics were seen in 11 of 19 (58%). 29 of 36 children (81%) had confirmed or suspected ADHD, and 12 of 24 had (50%) had obsessive or compulsive tendencies. Additional stereotypies, tics, ADHD and OCD behaviors were seen more often in head-shakers than non-head-shakers, but the number of non-head-shakers was too small to allow statistical comparison.

Oculomotor and vestibular testing was performed in 4 RES patients, 3 with head shaking and 1 without (Table 1). Oculomotor abnormalities were present in all 4 patients, including deficits in gaze-holding, smooth pursuit, saccades, and optokinetic nystagmus. Vestibular function was abnormal in all the patients with head shaking, but was normal in the 1 patient without head shaking.

TABLE 1.

Oculomotor and vestibular abnormalities in patients with RES

| Patient age and gender | Head shaking? | Gaze holding | Smooth pursuit gains | Saccades | Horizontal OKN gains | Sinusoidal VOR gains | Step VOR

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gains | Time constant | |||||||

| 12-y-old M | Yes | Stable | Low | Normal horizontal, hypometric vertical | Normal | Low at low frequency | Normal | Low |

| 7-y-old F | Yes | Stable, with occasional nystagmus | Very low | Normal horizontal and vertical | Low-normal | Normal | Normal | Very low |

| 6-y-old F | Yes | Nystagmus | Very low | Hypometric horizontal, variable vertical | Low-normal L, low R | Low | Very low | Very low |

| 3-y-old M | No | Stable | Very low | Hypometric horizontal, variable vertical | Very low | Normal | Normal | Normal |

Oculomotor and VOR values are normal when within 2SD of age-matched control values.

RES, rhombencephalosynapsis; VOR, vestibulo-ocular reflex; OKN, optokinetic nystagmus; M, male; F, female; L, left; R, right.

Discussion

Persistent, stereotyped figure-8 and side-to-side head shaking is remarkably common in patients with RES. Since this hindbrain malformation affects midline and paramidline cerebellar structures, the dysfunction may occur at the level of the vestibulocerebellum.

Repetitive head movements have been described in children with visual or oculomotor dysfunction. Head-rocking stereotypies are also seen in a minority of blind children, always in the presence of other motor stereotypies2. In contrast to patients with visual and oculomotor dysfunction, patients with RES have normal visual acuity and their head shaking remits when they are visually engaged.

Up-and-down head-bobbing in conjunction with cystic lesions of the third ventricle is referred to as bobble head doll syndrome (BHDS). The onset of these movements tends to be later than in RES patients, and the syndrome often remits entirely after decompression of the cystic lesion3. Repetitive head shaking movements such as those seen in our RES patients have sometimes been classified as a form of BHDS4,5, but these atypical presentations have been described in association with midbrain or cerebellar disorders rather than third ventricular lesions, suggesting that their underlying pathophysiology may be distinct.

In addition to a few reports that note head shaking in conjunction with RES6,7,8, side-to-side and figure-8 movements have been described in association with aqueductal stenosis7,4,5, Dandy-Walker malformation9, Joubert Syndrome10, occipital encephalocele with near-absent cerebellum (Doherty, personal observation), and in 2 children with cerebellar lesions presumably acquired early in development (Tully, personal observation)7. In contrast to patients with RES, the majority of patients with these other disorders do not exhibit head shaking. Those who do may have more profound vestibular processing defects. Furthermore, Ishak et al demonstrated that 5 of 56 patients with aqueductal stenosis had unrecognized RES1. This suggests that some children with head shaking associated with aqueductal stenosis may also have had underlying RES.

Though persistent head shaking is commonly associated with neurological impairment, it may also be observed transiently in normal infants11,12,13 and is a frequent topic of discussion among concerned parents on the internet14,15,16. Head shaking in developmentally normal infants has been ascribed to ear infections and teething14, but has also been characterized as a form of vestibular self-stimulation17,16. Though RES is compatible with a normal cognitive outcome, most patients have gross motor delay and strabismus, so would not ordinarily be viewed as typically developing.

Persistent figure-8 or side-to-side head shaking is one of the most recognizable clinical features of patients with RES. However, these individuals also exhibit other stereotypies, tics, and ADHD and OCD behaviors, suggesting that they may be particularly predisposed to developing repetitive movements in general. Stereotypies, tics, ADHD, and OCD have been associated with abnormalities in networks involving the frontal cortex and the basal ganglia18,19, and the influence of the cerebellum upon these networks is increasingly apparent20, 21,22. The array of neurobehavioral symptoms observed in association with RES may therefore be due to disrupted cerebellar modulation of cerebro-basal ganglia circuits. Alternatively, these symptoms may reflect more forebrain involvement than suggested by MRI.

We propose that head shaking in patients with RES is a response to a deficit in central vestibular processing. All 4 RES patients who underwent testing displayed oculomotor abnormalities, but the sole patient with normal vestibular function did not have persistent head shaking. Since head shaking is not observed when patients are trying to obtain visual information, its function is unlikely to be related to gaze stabilization. We hypothesize that head shaking in patients with RES is a non-volitional means of gaining additional sensory information. The figure-8 pattern activates all 3 semicircular canals as well as neck afferents and may therefore increase the output of a defective vestibular system. Alternatively, the movements may represent an underlying rhythmic motor pattern that is ordinarily suppressed in the presence of appropriate vestibular feedback.

We conclude that persistent figure-8 and side-to-side head shaking is an important marker of RES. This distinctive stereotypy, especially when accompanied by motor delay or strabismus, should prompt a careful search for an underlying malformation affecting the vestibulocerebellum.

Supplementary Material

Video 1: 21 month old boy with head shaking.

Video 2: 3 year old boy with head shaking. Note the cessation of movements with visual fixation.

Video 3: 8 year old girl with head shaking.

Video 4: 10 year old girl with head shaking. Note additional stereotypies (hand flapping) and cessation of movements with visual fixation.

Video 5: 27 year old woman with head shaking. This patient had been given a diagnosis of aqueductal stenosis in infancy. A clinician recognized the relationship between headshaking and hindbrain malformations, reviewed her MRI, and discovered previously unrecognized rhombencephalosynapsis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients with RES and their families, as well as the clinicians who referred them.

Author Roles:

1) Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Data Collection; 2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; 3) Manuscript: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and Critique.

HMT: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 3A

JCD: 1C, 2C, 3B

GEI: 1C, 3B

MPA: 1C, 3B

JWM: 1A, 3B

WBD: 1C, 3B

SMG: 1C, 2C, 3B

AHW: 1A, 1C, 3B

JOP: 1A, 1B, 1C, 3B

DD: 1A, 1C, 2C, 3B

Financial Disclosures:

HMT is employed by the University of Washington and has received institutional support from through a research training grant held by the Department of Neurology (NIH/NINDS, 5T32NS051171-05).

JCD is employed by the University of Washington

GEI is employed by the University of Washington

MPA is employed by the University of Washington and has received an honorarium from the Washington Dental Service Foundation.

JWM has received grants from the NINDS, CDC, FDA of the US Public Health Service, is a consultant for Medtronic, Inc., serves on a Data and Safety Monitoring Board for Edison Pharmaceuticals, and receives honoraria from the American Academy of Neurology and the Tourette Syndrome Association.

WBD is employed by the University of Washington and receives research support from the NIH/NINDS (R01 NS050375).

SMG is employed by the University of Washington and has received grant support from the Health Resources and Services Administration Maternal and Child Health Bureau.

AHW is employed by the University of Washington

JOP is employed by the University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Hospital

DD is employed by the University of Washington and receives research support from the NIH/NINDS (R01NS064077).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure/conflict of interest: No financial conflicts of interest. Please see “financial disclosures” section for full financial information for the past 12 months from each author.

References

- 1.Ishak GE, Dempsey JC, Shaw DW, et al. Rhombencephalosynapsis: a hindbrain malformation associated with incomplete separation of midbrain and forebrain, hydrocephalus and a broad spectrum of severity. Brain. 2012 doi: 10.1093/brain/aws065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fazzi E, Lanners J, Danova S, et al. Stereotyped behaviours in blind children. Brain Dev. 1999;21:522–528. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(99)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goikhman I, Zelnik N, Peled N, Michowiz S. Bobble-head doll syndrome: a surgically treatable condition manifested as a rare movement disorder. Mov Disord. 1998;13:192–194. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharyya KB, Senapati A, Basu S, Bhattacharya S, Ghosh S. Bobble-head doll syndrome: some atypical features with a new lesion and review of the literature. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;108:216–220. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nellhaus G. The bobble-head doll syndrome: a “tic” with a neuropathologic basis. Pediatrics. 1967;40:250–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brocks D, Irons M, Sadeghi-Najad A, McCauley R, Wheeler P. Gomez-Lopez-Hernandez syndrome: expansion of the phenotype. Am J Med Genet. 2000;94:405–408. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20001023)94:5<405::aid-ajmg12>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hottinger-Blanc PM, Ziegler AL, Deonna T. A special type of head stereotypies in children with developmental (?cerebellar) disorder: description of 8 cases and literature review. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2002;6:143–152. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.2002.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demaerel P, Kendall BE, Wilms G, Halpin SF, Casaer P, Baert AL. Uncommon posterior cranial fossa anomalies: MRI with clinical correlation. Neuroradiology. 1995;37:72–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00588525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Brito Henriques JG, Henriques KS, Filho GP, Fonseca LF, Cardoso F, Da Silva MC. Bobble-head doll syndrome associated with Dandy-Walker syndrome. Case report J Neurosurg. 2007;107:248–250. doi: 10.3171/PED-07/09/248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma SK, Shetty BS, Kanth L, Kumar T. A girl with abnormal head and eye movements: Joubert syndrome (2005:3b) Eur Radiol. 2005;15:1274–1276. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2568-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singer HS. Motor stereotypies. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2009;16:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris KM, Mahone EM, Singer HS. Nonautistic motor stereotypies: clinical features and longitudinal follow-up. Pediatr Neurol. 2008;38:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh D, Rajan PV, Erenberg G. A Comparative Study of Primary and Secondary Stereotypies. J Child Neurol. 2012 doi: 10.1177/0883073812464271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.http://www.steadyhealth.com/Baby_shaking_head_t93695.html [online]. Available.

- 15.http://www.babycenter.com/400_7-month-old-head-shaking_2520577_484.bc In.

- 16.www.mamapedia.com/article/6month-old-son-shaking-head [online]. Available.

- 17.Thelen E. Rhythmical stereotypies in normal human infants. Anim Behav. 1979;27:699–715. doi: 10.1016/0003-3472(79)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McNaught KS, Mink JW. Advances in understanding and treatment of Tourette syndrome. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:667–676. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singer HS. Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. 2011;100:641–657. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52014-2.00046-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoodley CJ, Schmahmann JD. Evidence for topographic organization in the cerebellum of motor control versus cognitive and affective processing. Cortex. 2010;46:831–844. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCairn KW, Iriki A, Isoda M. Global dysrhythmia of cerebro-basal ganglia-cerebellar networks underlies motor tics following striatal disinhibition. J Neurosci. 2013;33:697–708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4018-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strick PL, Dum RP, Fiez JA. Cerebellum and nonmotor function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:413–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video 1: 21 month old boy with head shaking.

Video 2: 3 year old boy with head shaking. Note the cessation of movements with visual fixation.

Video 3: 8 year old girl with head shaking.

Video 4: 10 year old girl with head shaking. Note additional stereotypies (hand flapping) and cessation of movements with visual fixation.

Video 5: 27 year old woman with head shaking. This patient had been given a diagnosis of aqueductal stenosis in infancy. A clinician recognized the relationship between headshaking and hindbrain malformations, reviewed her MRI, and discovered previously unrecognized rhombencephalosynapsis.