Abstract

Purpose

Although the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA) to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD) and some cancers, there are no estimates of lifetime risk of these non-communicable diseases according to PA levels. We aimed to estimate the lifetime risk of CVD and cancers according to PA levels.

Methods

We followed 5,807 men and 7,252 women in the U.S. age 45–64 initially free of CVD and cancer from 1987 through 2012, and used a life table approach to estimate lifetime risks of CVD (coronary heart disease, heart failure and stroke) and total cancer according to PA levels: poor (0 minutes/week of MVPA), intermediate (1–74 minutes/week of VPA or 1–149 minutes/week of MVPA) or recommended (≥75 minutes/week of VPA or ≥150 minutes/week of MVPA).

Results

During the 246,886 person-years of follow-up, we documented 4,065 CVD and 3,509 cancer events, and 2,062 non-CVD and 2,326 non-cancer deaths. In men, the lifetime risks of CVD from 45 through 85 years were 52.7% (95% confidence interval, 49.4–55.5) for poor PA and 45.7% (42.7–48.3) for recommended PA. In women, the respective lifetime risks of CVD were 42.4% (39.5–44.9) and 30.5% (27.5–33.1). Lifetime risks of total cancer in men were 40.1% (36.9–42.7) for poor PA and 42.6% (39.7–45.2) for recommended activity; in women, 31.4% (28.7–33.8) and 30.4% (27.7–32.9), respectively.

Conclusions

Compared with a poor PA level, WHO recommended PA was associated with lower lifetime risk of CVD, but not total cancer, in both men and women.

Keywords: ARIC study, WHO, risk factor, non-communicable disease

INTRODUCTION

Non-communicable diseases (NCD) are responsible for 38 million global deaths, and 16 million NCD deaths are premature (39). Most NCD deaths (68%) derive from cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer (39), and thus it is essential to prevent these two diseases for the prevention of premature deaths.

Physical inactivity is considered to be one of the most important modifiable risk factors for NCD (39). Abundant reports have suggested that physical inactivity is associated with increased risks of coronary heart disease (37), stroke (8), heart failure (7), and cancer (20). Physical activity may reduce the risk of CVD or cancer through preventing obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and glucose intolerance (20, 22, 29). In addition, several previous studies suggested direct effects of physical activity, such as improved endothelial function or immune function, and reduced systemic inflammation, platelet aggregation, estrone/estradiol levels, or oxidative stress (10, 12, 20).

A World Health Organization (WHO) guideline on physical activity recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, at least 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity throughout the week (40). In order to encourage people to achieve this level, it is important to cultivate an understanding of its potential impact on major NCD risk. One way for that may be to provide information on the lifetime risk of major NCD according to physical activity levels. Lifetime risk estimates, which are absolute risks to a certain age, are often more easily understood than relative risks (15–17). However, to our knowledge, there has been no study estimating lifetime NCD risks according to physical activity levels.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to estimate the lifetime risk of incident CVD and cancer in a U.S. cohort, according to physical activity levels based on the WHO recommendation, separately for men and women.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Population

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study is an ongoing population-based prospective study of cardiovascular diseases (14, 38). In 1987–1989, the ARIC Study recruited and examined 15,792 mostly Caucasian or African American men and women aged 45–64 from 4 U.S. communities [Washington County, Maryland; Forsyth County, North Carolina; Jackson, Mississippi (African Americans only); and suburbs of Minneapolis, Minnesota]. The baseline home interview and clinic examination measured various chronic disease risk factors, health behaviors, and cardiovascular conditions. Participants were followed through 2012 for this report. The institutional review boards of the collaborating institutions approved the study protocol, and each participant provided written informed consent.

Risk Factor Measurements

The main exposure of interest was baseline physical activity. We assessed sports physical activity via an interviewer administered Baecke questionnaire (3). The reliability and validity of the Baecke questionnaire were evaluated in several populations and summarized elsewhere (11, 30, 38). The Baecke questionnaire asked participants to report the frequency and the number of hours of participation in as many as 4 sports or leisure activities in the previous year. As in prior ARIC studies (5, 35), each activity was converted into metabolic equivalents of task (METs) using the Compendium of Physical Activities (1). Moderate activities were defined as those involving 3–6 METs intensity and vigorous activities were those involving >6 METs intensity (1). Information from the questionnaires was subsequently converted into minutes/week of moderate or vigorous physical activity, and participants were categorized into three groups: “recommended” [based on the WHO recommendation (40) of ≥75 minutes/week of vigorous intensity or ≥150 minutes/week of any combination of moderate + vigorous intensity], “intermediate” (1–74 minutes/week of vigorous intensity or 1–149 minutes/week of any combination of moderate + vigorous intensity), or “poor” (0 minutes/week of moderate or vigorous intensity).

We also assessed potential confounding factors, including race, smoking status, and a healthy diet score, and lung diseases (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and restrictive lung disease). Diet was assessed by a slightly modified, 66-item Harvard food frequency questionnaire (31), and a healthy diet score was calculated by adding each point (0 or 1) of the following 5 healthy dietary metrics: ≥4.5 cups/day of fruits and vegetables (approximated as ≥4.5 servings/day in the ARIC study); 2 or more ≥3.5-oz servings/week of fish (approximated as 3- to 5-oz servings/week); 3 or more 1-oz servings/day of whole grains (approximated as ≥3 servings/day); sodium (<1,500 mg/day); and ≤36 oz/week of sugar-sweetened beverages (approximated as ≤4 glasses/week). We defined individuals with lung diseases as those with forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC)< lower limit of normal (LLN) (chronic obstructive lung disease), those with FEV1/FVC≥LLN and FVC<LLN (restrictive lung disease), or those who self-reported chronic bronchitis, emphysema or asthma (13).

Confirmation of Cardiovascular Disease and Total Cancer

We defined incident CVD events as coronary heart disease, heart failure, and stroke. ARIC staff contacted participants or their proxies annually by telephone to capture all hospitalizations and deaths related to possible CVD (9). They also surveyed lists of discharges from local hospitals and death certificates from state vital statistics offices for potential CVD events. Abstractors reviewed medical records and recorded information to validate CVD outcomes. Incident coronary heart disease was validated by physician review, and was defined as a definite or probable myocardial infarction, definite coronary death, or coronary revascularization procedure. Incident heart failure was defined as the first occurrence of either a hospitalization that included an International Classification of Diseases-9th Revision (ICD-9) discharge code of 428 (428.0 to 428.9) among the primary or secondary diagnoses or else a death certificate with an ICD-9 code of 428 or an ICD-10 code of I50 among the listed or underlying causes of death (18). ARIC has shown the validity of ICD-9 Code 428 to be moderately high, with a sensitivity of 93% for identifying acute decompensated heart failure (32). For patients hospitalized for potential strokes, the abstractors recorded signs and symptoms and photocopied neuroimaging (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) and other diagnostic reports. Using criteria adopted from the National Survey of Stroke, definite or probable strokes were classified by computer algorithm and separately reviewed by a physician, with disagreements resolved by a second physician (24).

Incident cancer cases were obtained by linking to cancer registries (28). ARIC hospital surveillance was used to identify additional cancer cases. For participants who had hospital ICD codes for cancer but were not in cancer registries, including those who may have moved, records of hospitalized events were obtained. Primary site and date of cancer diagnosis were obtained. If a participant had more than 1 type of incident cancer during follow-up, the earliest date of cancer incidence was chosen for analysis of the combined, total cancer end point.

Statistical Analysis

SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for statistical analyses.

We excluded participants who reported or had electrocardiographic evidence of prebaseline CVD or cancer (n=2,342) and participants whose data on physical activity or outcome status were missing (n=391). After exclusions, 13,059 participants initially free of CVD and cancer were followed from 1987 through 2012 or until death and included in the analyses.

We estimated sex-specific remaining lifetime risks of incident CVD or total cancer through age 85 years according to physical activity levels, using a modified version of survival analysis (4) as previous studies described (15–17). We separately estimated cumulative risks for CVD and for total cancer. This method uses survival age as the time scale, combines information on participants entering the observation periods at different ages, and accounts for varying durations of follow-up of individuals (4). In addition, it takes into account the occurrence of competing risks of death from other causes through adjustment to yield estimates of age-specific hazards and incidence rates as well as cumulative incidences, and survival probabilities. In contrast, traditional Kaplan-Meier estimates do not properly account for competing risks, often resulting in overestimates of the remaining lifetime risk (15–17).

Because the lifetime risk model cannot adjust for confounding variables, we stratified participants by potential confounding factors—race (African American vs. white), smoking status (current vs. non-current), healthy diet score (≤1 vs. ≥2 points), and presence vs. absence of lung diseases—and examined lifetime risks of CVD and total cancer within strata. Risk factors that could be a consequence of physical inactivity and potentially mediate its effects, such as obesity, hypertension and dyslipidemia were not considered confounders and, thus, not evaluated.

RESULTS

During 1987–2012 (mean ± standard deviation: 18.9 ± 7.2 years), 13,059 participants (5,807 men and 7,252 women) provided 246,886 person-years of observation. During the follow-up, we documented 4,065 incident CVD (coronary heart disease, heart failure or stroke) and 3,509 cancer events, and 2,062 non-CVD and 2,326 non-cancer deaths. The overall lifetime risks to age 85 of total CVD, coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke and total cancer were 49.1%, 34.2%, 25.3% 11.2% and 41.1% for men, and 37.5%, 18.1%, 23.6% 10.5% and 30.0% for women, respectively.

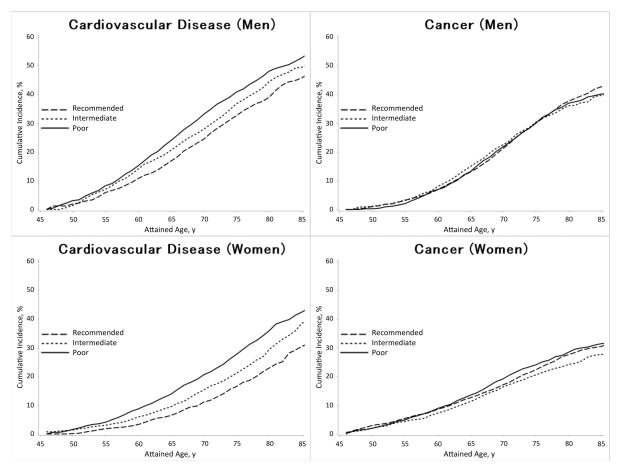

The remaining lifetime risks of incident CVD and total cancer at ages 45, 55, and 65 years are shown according to physical activity levels in Table 1. The lifetime risks were generally higher among men than among women. Physical activity displayed an inverse dose-response relation with lifetime risks of CVD, such that CVD was 2–8 % lower in men and women at any index age for each higher physical activity category (i.e. poor to intermediate or intermediate to recommended). Similar trends for physical activity and lifetime risks of CVD were observed in all strata of race, smoking status, healthy diet score and with or without lung diseases (Table 2). On the other hand, the lifetime risks of total cancer did not appreciably differ across physical activity levels in both men and women. The remaining lifetime risks of CVD and total cancer at age 45 years are illustrated in Figure 1. In men, the lifetime risks of CVD from 45 through 85 years were 52.7% for poor physical activity and 45.7% for recommended physical activity. In women, the respective lifetime risks of CVD were 42.4% and 30.5%. Lifetime risks of total cancer at age 45 years in men were 40.1% for poor physical activity and 42.6% for recommended activity; in women, 31.4% and 30.4%, respectively (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Remaining Lifetime Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Total Cancer from Selected Index Ages to 85 Years According to Physical Activity Levels, ARIC, 1987–2012.

| Index age, years | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime risk (%) to 85y (95% confidence interval)

|

Lifetime risk (%) to 85y (95% confidence interval)

|

|||||

| Poor | Intermediate | Recommended | Poor | Intermediate | Recommended | |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||||

| 45 | 52.7 (49.4–55.5) | 49.4 (45.3–52.9) | 45.7 (42.7–48.3) | 42.4 (39.5–44.9) | 38.6 (34.8–42.1) | 30.5 (27.5–33.1) |

| 55 | 49.6 (46.1–52.4) | 46.4 (42.2–50.0) | 42.7 (39.6–45.3) | 40.7 (37.7–43.2) | 37.2 (33.5–40.5) | 29.4 (26.4–32.1) |

| 65 | 42.5 (38.3–45.8) | 39.2 (34.4–43.3) | 36.6 (33.2–39.4) | 35.3 (32.2–38.1) | 33.4 (29.5–36.8) | 26.6 (23.5–29.3) |

| Total cancer | ||||||

| 45 | 40.1 (36.9–42.7) | 39.6 (35.6–43.0) | 42.6 (39.7–45.2) | 31.4 (28.7–33.8) | 27.6 (24.6–30.3) | 30.4 (27.7–32.9) |

| 55 | 40.2 (37.0–42.8) | 38.5 (34.5–41.8) | 41.3 (38.3–43.8) | 28.2 (25.7–30.3) | 24.5 (21.7–27.0) | 26.6 (24.2–28.9) |

| 65 | 34.9 (31.3–37.7) | 31.3 (27.0–35.0) | 35.5 (32.3–38.2) | 21.9 (19.3–24.1) | 19.0 (16.2–21.5) | 21.0 (18.5–23.2) |

Table 2.

Remaining Lifetime Risk of Cardiovascular Disease from Selected Index Ages to 85 Years According to Physical Activity Levels, Stratified by Race, Smoking Status or Healthy Diet Score, ARIC, 1987–2012.

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime risk (%) to 85y (95% confidence interval)

|

Lifetime risk (%) to 85y (95% confidence interval)

|

|||||

| Poor | Intermediate | Recommended | Poor | Intermediate | Recommended | |

| African American | 55.0 (49.6–59.7) | 47.4 (37.2–55.3) | 45.4 (37.0–52.3) | 45.7 (41.6–49.4) | 45.6 (37.4–52.6) | 37.6 (29.1–44.7) |

| White | 51.6 (47.3–55.1) | 50.2 (45.8–54.2) | 45.6 (42.4–48.4) | 39.5 (35.5–42.9) | 36.5 (32.2–40.6) | 29.0 (25.8–31.8) |

| Current smokers | 54.7 (50.8–57.9) | 51.3 (46.5–55.5) | 48.1 (44.4–51.3) | 48.9 (44.5–52.5) | 45.9 (39.9–52.0) | 33.7 (28.8–37.8) |

| Non-current smokers | 46.5 (40.0–52.0) | 44.7 (37.2–51.3) | 39.9 (34.9–44.4) | 36.4 (32.6–39.7) | 32.9 (28.1–37.0) | 27.9 (24.1–31.4) |

| Diet score ≤1 | 54.5 (49.7–58.5) | 50.8 (43.9–56.4) | 46.7 (41.1–43.6) | 44.2 (38.6–48.9) | 39.5 (32.1–46.1) | 33.3 (25.3–40.3) |

| Diet score ≥2 | 51.0 (46.2–55.1) | 48.6 (43.4–53.2) | 45.2 (41.6–48.4) | 41.3 (37.8–44.2) | 38.8 (34.3–43.1) | 29.8 (26.5–32.7) |

| With lung diseases | 54.9 (49.3–59.6) | 53.2 (45.6–59.4) | 48.3 (43.0–52.9) | 46.2 (41.1–50.5) | 48.5 (41.0–55.9) | 35.0 (29.3–39.9) |

| Without lung diseases | 51.5 (47.4–55.0) | 47.9 (42.9–52.2) | 44.7 (41.1–47.8) | 40.6 (37.1–43.7) | 34.8 (30.5–38.6) | 28.6 (25.1–31.7) |

Lung diseases were defined as forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC)< lower limit of normal (LLN) (chronic obstructive lung disease), FEV1/FVC≥LLN and FVC<LLN (restrictive lung disease), or self-reported chronic bronchitis, emphysema or asthma.

Figure 1.

Sex-specific lifetime risk estimates of cardiovascular disease and total cancer at age 45 to 85 years according to physical activity levels based on the WHO recommendation, ARIC, 1987–2012.

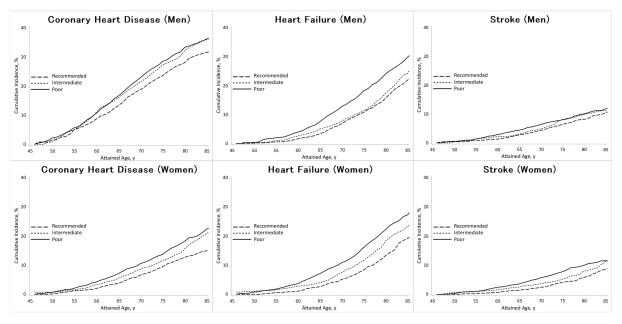

We also estimated the lifetime risks from age 45 to 85 years of CVD subtypes—coronary heart disease, heart failure and stroke—according to physical activity levels (Figure 2). In men, the lifetime risks of coronary heart disease were 36.2% for poor physical activity and 31.6% for recommended physical activity, those of heart failure were 29.8% for poor physical activity and 21.9% for recommended activity, and those of stroke were 11.9% for poor physical activity and 10.5% for recommended activity; in women, the lifetime risks of coronary heart disease were 20.8% for poor physical activity and 12.8% for recommended physical activity, those of heart failure were 27.3% for poor physical activity and 19.2% for recommended activity, and those of stroke were 11.5 % for poor physical activity and 8.6% for recommended activity.

Figure 2.

Sex-specific lifetime risk estimates of coronary heart disease, heart failure and stroke at age 45 to 85 years according to physical activity levels based on the WHO recommendation, ARIC, 1987–2012

We also ran models after combining men and women and obtained similar results. [See Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease and total cancer according to physical activity levels among men and women. See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, lifetime risk estimates of cardiovascular disease and total cancer according to physical activity levels based on the WHO recommendation among men and women. See Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease according to physical activity levels, stratified by several factors among men and women. See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 4, lifetime risk estimates of coronary heart disease, heart failure and stroke according to physical activity levels based on the WHO recommendation among men and women.]

DISCUSSION

In this population-based prospective study in the U.S., we estimated the remaining lifetime risk of incident CVD and total cancer according to baseline physical activity levels based on WHO recommendation. Compared with people who were inactive, men meeting the WHO-recommended physical activity level had 7% lower lifetime risk of CVD from age 45 to age 85 years (46% vs. 53%) and women had 11% lower risk (31% vs. 42%). The lifetime risks of total cancer were approximately 41% for men and 30% for women regardless of physical activity levels. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the lifetime risk of incident CVD and total cancer in both men and women according to physical activity levels.

Lifetime risk reductions were similar when projected from index ages of 45, 55 or 65 years, and the pattern was similar after stratifying by race, smoking status, healthy diet score, and with or without lung diseases. A previous study, which examined lifetime risk of CVD in relation to cardiovascular fitness, but not physical activity, showed a comparable reduction in the lifetime risk of CVD (about 9%) among men with a high level of cardiovascular fitness compared to those with a low level (6). The WHO recommended level of physical activity was associated with a reduced lifetime risk of CVD, but those who met WHO recommendation still had a substantial lifetime risk of CVD. Thus, people must avoid additional risk factors such as smoking and unhealthy diet to further reduce their lifetime risk of CVD.

The Framingham Study, which started in 1948, reported lifetime risks of coronary heart disease which were approximately 50% for men and 30% for women (15), lifetime risks of heart failure in absence of antecedent myocardial infarction which were approximately 20% for both men and women (16), and lifetime risks of stroke which were approximately 15% for men and 20% for women (34). In the ARIC cohort of 45–64 year olds at baseline starting in 1987, we found overall lifetime risks of coronary heart disease and stroke were lower than for the Framingham cohort. ARIC estimates of lifetime risk of heart failure were higher than Framingham, but our estimate did not exclude heart failure with antecedent coronary heart disease. Lower lifetime risks of CVD in a younger cohort are expected given the decline in CVD in the U.S. over the past three decades.

The National Cancer Institute has reported lifetime risks of invasive cancer at age 40 years through death in the U.S. are approximately 42% for men and 37% for women (23). We observed a similar lifetime risk at age 45 through 85 for men (about 41%). We observed a slightly lower lifetime risk at age 45 through 85 for women (about 30%); this could be due, in part, to the relatively higher proportion of African American participants in ARIC as compared to the United States. While lifetime risk of invasive cancer is comparable for men by race, it is slightly lower among African American women than white women. In contrast to CVD, cancer showed no clear difference in lifetime risks across physical activity levels, even though a previous study have reported higher relative risks of certain cancers for physically inactive compared with active adults (20). In addition, physical activity is also associated with reduced risk of cancer mortality (26), and greater gains in life expectancy among cancer survivors (21). Generally, the association between physical activity and the most common cancers in ARIC has been weak. For example, in ARIC physical activity was not associated with breast cancer during early follow-up (19), although other studies have reported a relatively strong inverse association regardless of menopausal status (25). Among ARIC men, the most common cancers are prostate and lung, neither of which are strongly associated with physical activity. Thus, although the present study did not show an inverse association between physical activity and lifetime cancer risk, there may be beneficial effects of physical activity on certain cancers.

Generally speaking, it is difficult to achieve the recommended level of physical activity for health benefits during work alone. Leisure-time physical activities, sports, and exercise have consistently been reported to be associated with health benefits (2, 27, 33). In addition, even individuals performing all their exercise in 1 or 2 sessions per week like “weekend warriors” appear to have decreased risk of mortality (27). In contrast, whether domestic physical activities convey health benefits appears controversial (33, 36). This discrepancy may be partially because sports and exercises offer more aerobic activity. Thus, it may be most practical to recommend leisure-time physical activities in order to achieve health benefits.

Some limitations of our study need to be addressed. First, estimates of lifetime risks of CVD and total cancer should be carefully interpreted, as they may be to some degree confounded by other risk factors, such as smoking and diet, though we showed similar patterns within strata of smoking and healthy diet score. Nonetheless, these estimates of lifetime risk may be helpful from a policy perspective to determine where public health resources should be allocated. Second, physical activity levels were measured via a questionnaire, and are subject to measurement error. Misclassification of physical activity would tend to attenuate the estimated difference in lifetime risks between active and inactive adults. Third, as pointed out above, estimates of lifetime risk are subject to birth cohort effects and therefore can change over time. Fourth, the estimates of lifetime risk that we present are conditional on survival to the baseline ARIC survey without the event of interest and are computed to age 85. Fifth, we used data on physical activity only at baseline. Thus, we cannot negate the possibility that changes of physical activity during follow-up might have affected our results. Finally, we estimated lifetime risk of total cancer but not site-specific cancers, because site-specific cancer data are not available yet in ARIC. Physical activity may be associated with a lower lifetime risk of certain cancers, such as colorectal and breast cancer. Thus, further studies will be needed for the association between physical activity and lifetime risks of site-specific cancers.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, in the prospective population-based ARIC cohort, the WHO-recommended level of physical activity was associated with lower lifetime risk of CVD, but not total cancer, compared with intermediate or poor levels of activity.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1, lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease and total cancer according to physical activity levels among men and women

Supplemental Digital Content 2, lifetime risk estimates of cardiovascular disease and total cancer according to physical activity levels based on the WHO recommendation among men and women

Supplemental Digital Content 3, lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease according to physical activity levels, stratified by several factors among men and women

Supplemental Digital Content 4, lifetime risk estimates of coronary heart disease, heart failure and stroke according to physical activity levels based on the WHO recommendation among men and women

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

The results of the study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation

The Nippon Foundation provided grants to support Dr. Kubota’s fellowship at School of Public Health, University of Minnesota. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) supported ARIC via contracts HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C. Studies on cancer in ARIC are also supported by the National Cancer Institute (U01 CA164975). The content of this work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Cancer incidence data have been provided by the Maryland Cancer Registry, Center for Cancer Surveillance and Control, Department of Mental Health and Hygiene, 201 W. Preston Street, Room 400, Baltimore, MD 21201. We acknowledge the State of Maryland, the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund, and the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for the funds that helped support the availability of the cancer registry data.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

References

- 1.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9 Suppl):S498–504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arem H, Moore SC, Patel A, et al. Leisure time physical activity and mortality: a detailed pooled analysis of the dose-response relationship. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):959–67. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36(5):936–42. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beiser A, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Seshadri S, Sullivan LM, Wolf PA. Computing estimates of incidence, including lifetime risk: Alzheimer’s disease in the Framingham Study. The Practical Incidence Estimators (PIE) macro. Stat Med. 2000;19(11–12):1495–522. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000615/30)19:11/12<1495::aid-sim441>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell EJ, Lutsey PL, Windham BG, Folsom AR. Physical activity and cardiovascular disease in African Americans in Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2013;45(5):901–7. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31827d87ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry JD, Willis B, Gupta S, et al. Lifetime risks for cardiovascular disease mortality by cardiorespiratory fitness levels measured at ages 45, 55, and 65 years in men. The Cooper Center Longitudinal Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(15):1604–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Butler J, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC. Association of Physical Activity or Fitness With Incident Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8(5):853–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evenson KR, Rosamond WD, Cai J, et al. Physical activity and ischemic stroke risk. The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Stroke. 1999;30(7):1333–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.7.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folsom AR, Alonso A, Misialek JR, et al. Parathyroid hormone concentration and risk of cardiovascular diseases: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am Heart J. 2014;168(3):296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hambrecht R, Wolf A, Gielen S, et al. Effect of exercise on coronary endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(7):454–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002173420702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs DR, Jr, Ainsworth BE, Hartman TJ, Leon AS. A simultaneous evaluation of 10 commonly used physical activity questionnaires. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25(1):81–91. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koenig W, Sund M, Döring A, Ernst E. Leisure-time physical activity but not work-related physical activity is associated with decreased plasma viscosity. Results from a large population sample. Circulation. 1997;95(2):335–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubota Y, London SJ, Cushman M, et al. Lung function, respiratory symptoms and venous thromboembolism risk: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(12):2394–2401. doi: 10.1111/jth.13525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubota Y, McAdams-DeMarco M, Folsom AR. Serum uric acid, gout, and venous thromboembolism: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Thromb Res. 2016;144:144–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lloyd-Jones DM, Larson MG, Beiser A, Levy D. Lifetime risk of developing coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1999;353(9147):89–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lloyd-Jones DM, Larson MG, Leip EP, et al. Lifetime risk for developing congestive heart failure: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2002;106(24):3068–72. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039105.49749.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lloyd-Jones DM, Leip EP, Larson MG, et al. Prediction of lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease by risk factor burden at 50 years of age. Circulation. 2006;113(6):791–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.548206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loehr LR, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Folsom AR, Chambless LE. Heart failure incidence and survival (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study) Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(7):1016–22. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mertens AJ, Sweeney C, Shahar E, Rosamond WD, Folsom AR. Physical activity and breast cancer incidence in middle-aged women: a prospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97(2):209–14. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore SC, Lee IM, Weiderpass E, et al. Association of Leisure-Time Physical Activity With Risk of 26 Types of Cancer in 1.44 Million Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(6):816–25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore SC, Patel AV, Matthews CE, et al. Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: a large pooled cohort analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):e1001335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mora S, Cook N, Buring JE, Ridker PM, Lee IM. Physical activity and reduced risk of cardiovascular events: potential mediating mechanisms. Circulation. 2007;116(19):2110–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cancer Institute homepage [Internet] USA: [updated 2016 Apr; cited 2016 Nov. 23]. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2012/results_merged/topic_lifetime_risk.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Survey of Stroke. National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke. Stroke. 1981;12(2 Pt 2 Suppl 1):I1–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neilson HK, Farris MS, Stone CR, Vaska MM, Brenner DR, Friedenreich CM. Moderate-vigorous recreational physical activity and breast cancer risk, stratified by menopause status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause. 2017;24(3):322–344. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Donovan G, Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Relationships between exercise, smoking habit and mortality in more than 100,000 adults. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(8):1819–1827. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Donovan G, Lee IM, Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Association of “Weekend Warrior” and Other Leisure Time Physical Activity Patterns With Risks for All-Cause, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer Mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8014. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rasmussen-Torvik LJ, Shay CM, Abramson JG, et al. Ideal cardiovascular health is inversely associated with incident cancer: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities study. Circulation. 2013;127(12):1270–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371(9612):569–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richardson MT, Ainsworth BE, Wu HC, Jacobs DR, Jr, Leon AS. Ability of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC)/Baecke Questionnaire to assess leisure-time physical activity. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;2(4):685–93. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(10):1114–26. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116211. discussion 1127–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Baggett C, et al. Classification of heart failure in the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study: a comparison of diagnostic criteria. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(2):152–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabia S, Dugravot A, Kivimaki M, Brunner E, Shipley MJ, Singh-Manoux A. Effect of intensity and type of physical activity on mortality: results from the Whitehall II cohort study. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(4):698–704. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seshadri S, Beiser A, Kelly-Hayes M, et al. The lifetime risk of stroke: estimates from the Framingham Study. Stroke. 2006;37(2):345–50. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000199613.38911.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah AM, Claggett B, Folsom AR, et al. Ideal Cardiovascular Health During Adult Life and Cardiovascular Structure and Function Among the Elderly. Circulation. 2015;132(21):1979–89. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stamatakis E, Hamer M, Lawlor DA. Physical activity, mortality, and cardiovascular disease: is domestic physical activity beneficial? The Scottish Health Survey -- 1995, 1998, and 2003. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(10):1191–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanasescu M, Leitzmann MF, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB. Exercise type and intensity in relation to coronary heart disease in men. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1994–2000. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. The ARIC Investigators. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization homepage [Internet] Switzerland: [updated 2015 Jan; cited 2016 Nov. 23]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs355/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Geneva (Switzerland): 2010. p. 8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1, lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease and total cancer according to physical activity levels among men and women

Supplemental Digital Content 2, lifetime risk estimates of cardiovascular disease and total cancer according to physical activity levels based on the WHO recommendation among men and women

Supplemental Digital Content 3, lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease according to physical activity levels, stratified by several factors among men and women

Supplemental Digital Content 4, lifetime risk estimates of coronary heart disease, heart failure and stroke according to physical activity levels based on the WHO recommendation among men and women