Abstract

We previously demonstrated that detectable BK virus (BKV) replication in donor urine pre- transplant was significantly associated with post-transplant recipient BKV viremia. In this 4-year prospective study, we assessed whether recipient BKV replication pre-transplant was associated with post-transplant viremia/BKV nephropathy. We studied 220 primary adult and pediatric organ transplant recipients for 490 person-years and 2100 clinical visits. BKV viruria was detectable in 28 (16%), 26 adults and 2 children; and viremia in none pre- transplant. Post-transplant viruria occurred in all recipients with pre-transplant BKV viruria; significantly more than in recipients without pre-transplant viruria on univariate (p <0.005) and multivariate analysis including type of organ transplanted and immunosuppression type (p 0.008). Time to post-transplant viruria was significantly shorter in recipients with pre-transplant viruria (p 0.01). By univariate and multivariate analysis, BKV viruria in recipients pre-transplant did not impact post-transplant BKV viremia (p=0.97 and 0.97 respectively) even when stratified by type of organ transplant (kidney p=0.6; liver p=0.5). The peak serum and urine BKV PCR post-transplant was not significantly different in patients with pre-transplant BKV viruria and no one developed BK nephropathy. In conclusion, recipient BKV viruria prior to transplant predicts post-transplant viruria but not viremia or BKV nephropathy.

Introduction

The BK virus (BKV), a human renotropic polyoma virus, was discovered in 1971 (1) and since then has been identified as a significant cause of renal allograft dysfunction and loss with the first documented case of BKV nephropathy being published in 1995 (2). Infections with BKV are highly prevalent and after primary infection, which occurs most commonly in childhood, the viruses persist in renal tubular and uroepithelial cells that serve as reservoirs for reactivation (3). BKV nephropathy is more common in kidney transplant recipients but can also occur in other immunocompromised transplant recipients (4–7) and BKV infection even without overt nephropathy has been shown to be associated with renal impairment in kidney, liver (8), lung (9) and heart (10) transplant recipients.

We previously showed that donor BKV viruria was associated with increased recipient BKV viremia post-transplant (11). The role of pre-transplant recipient BKV replication on subsequent post-transplant BKV infection is less defined. While pre-transplant BK viral replication has been postulated to be a risk factor for post-transplant infection (12), other studies negate this (13–15). We conducted a 4-year prospective study of recipient viral replication in the urine, oral wash and blood before and after pediatric and adult transplant to study the incidence and role of pre-transplant recipient BKV replication on post-transplant recipient BKV outcomes.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

All subjects receiving an organ transplant at the University of Minnesota were consecutively enrolled just prior to transplant and followed for as long as 4 years. Donors and recipients were studied 1–7 days prior to transplant; then recipients were studied approximately every 3 months after transplantation for quantitative viral shedding of BKV in oral washes, urine, and ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) anti-coagulated whole blood. All recipients received antiviral prophylaxis with valganciclovir (450mg daily if creatinine clearance was 40–60mL/min; 900mg daily if clearance was >60mL/min; or 15mg/kg in children with maximum dose of 900mg daily depending on creatinine clearance) for at least 3 months. All recipients received thymoglobulin induction immunosuppression and maintenance therapy with a calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus/FK or cyclosporine/CSA) and an anti-metabolite (azathioprine/AZA or mycophenolate/MMF) with or without prednisone. A few recipients had immunosuppression protocols that included transition to sirolimus (n=43).

Demographic and clinical data on infections, graft and subject outcomes were obtained from the database of prospectively recorded demographics and outcomes data for all transplants performed at the University of Minnesota. This study was approved by the Research Subjects Protection Program of the University of Minnesota (IRB # 0804M31463) and informed consent was obtained from recipients before participation.

Quantitative viral DNA assays

Viral DNA was extracted from the samples using the QIAamp® DNA minikit (QIAGEN, Inc, Valencia, CA). The matrix tested was either anti-coagulated whole blood or urine. BKV viral loads were measured by real-time quantitative TaqMan PCR assays, all of which have been developed and validated in our Clinical Virology Research Laboratory in collaboration with the University of Minnesota Medical Center-Fairview Clinical Virology Laboratory. The assays were run on either an ABI 7000 or an ABI 7700 oligonucleotide sequence detector. The primers and probes were designed and optimized using Primer Express® software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The probe was: 5′-(FAM) ACC CGT GCA AGT GCC AAA ACT ACT AAT AAA AGG (TAM)-3′. The forward primer was 5′-GCA GC CCC AAA AAG CCA AAT-3′. The reverse primer was 5′-CTG GGT TTA GGA AGC ATT CTA-3′.

Data gathering, data coordination, and statistics

The following data were evaluated:

Recipient serial measurements of BKV viral loads were treated as categorical variables. A positive viral load was defined as BKV, ≥500 copies/mL of sample.

All physician-initiated treatment of viral disease was recorded. Viral shedding, BKV viruria, viremia and disease definitions were as follows: Viral shedding was defined as a positive BKV viral load in any specimen; BKV viruria was detection of BKV DNA in a specimen of urine; BKV DNAemia or viremia was detection of BKV DNA in a specimen of whole blood and BKV disease was a pathologic diagnosis of BKV nephropathy from a renal biopsy.

Donor and recipient demographics (age, race and gender) and virology data were analyzed. Pearsons χ2 test of association was used to assess the association between recipient viral shedding and post-transplant recipient viral shedding for BKV. Multivariate analysis including type of organ transplanted and immunosuppression type was also done to assess the association between recipient viral shedding and post-transplant recipient viral shedding for BKV. Actuarial BKV viremia-free survival rates were computed by the Kaplan-Meier method. Viremia-free survival was compared for subjects with and without recipients shedding BK virus pre-transplant using log-rank analysis. Since 48 recipients did not have pre-transplant urinary specimens due to anuric/oliguric renal failure, the analysis was repeated in the remaining 172 recipients. Statistical significance was set at a p value <0.05, two sided. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 11.0 software (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

In this 4 year prospective study, we studied 220 primary organ transplant recipients for 490 person-years. We conducted 2,100 clinical visits (2–20 visits/recipient) and collected and tested 9,081 samples of blood, urine and oral washes for the quantitative measurement of BKV in primary solid-organ transplant recipients and their donors beginning 1–7 days before the transplant [Table 1].

TABLE 1.

Demographics of 220 Transplant Recipients Enrolled in the Prospective Transplant Viral Monitoring Study Performed at the University of Minnesota

| Characteristic | Number of Subjects or Mean Value |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Kidney | 111 (51%) |

| Liver | 67 (31%) |

| Kidney-Liver | 3 (1%) |

| Kidney-pancreas | 8 (4%) |

| Lung | 28 (12%) |

| Pancreas | 3 (1%) |

|

| |

| Pediatric Transplants | 28 (13%) |

| Female | 11 |

| Age | 8+/6.1 (6m–17.9y) |

| Organ | 21 Kidney; 7 Liver |

|

| |

| Recipient | |

| Mean age in years (range) | 46.6+/−19 (6 mo–79 yrs) |

| Females | 81 (37%) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 186 (85%) |

| African American | 17 (8%) |

|

| |

| Donor | |

| Deceased/LRD/LURD | 125 (57%)/50 (23%)/45 (20%) |

| Donor age | 38+/−15.4 (0.47–72.8) |

| Female | 107 (49%) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 201 (91%) |

| African American | 8 (4%) |

|

| |

| Total number of subject visits | 2100 |

|

| |

| Mean number of clinic visits/recipient (range) | 9.5 (2–20) |

|

| |

| Total number of recipient samples | 9081 |

|

| |

| Mean follow-up in days/recipient: mean (range) | 818 (41–1551) |

|

| |

| Failed transplant | 14 |

The majority of recipients included were kidney (51%) and liver (31%) recipients. The mean age of recipients was 46.6 years; 28 were pediatric recipients; 37% were female; 85% were Caucasian and 57% were deceased donor recipients. All recipients were noted to receive thymoglobulin induction and maintenance immunosuppression varied as noted in Table 2. Donors were mostly Caucasian and female.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of recipients with and without pre-transplant (tx) BK viruria

| Pre-transplant BK viruria | Positive (n=28) | Negative (n=192) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Female | 12 (42.9%) | 69 | 0.5 |

|

| |||

| Age | 51.8 ± 15.8 [15.5–78.7] |

45.8 ±19.4 [0.5–73.3] |

0.5 |

|

| |||

| Organ: | 0.4 | ||

| Kidney | 15 (53.6%) | 96 (35.9%) | |

| Kidney-Liver | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Kidney-pancreas | 0 | 8 (4.2%) | |

| Liver | 6 (21.5%) | 61 (31.8%) | |

| Lung | 5 (17.9%) | 23 (12%) | |

| Pancreas | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (1%) | |

|

| |||

| Race: | 0.6 | ||

| Caucasian | 26 (92.8%) | 160 (83.3%) | |

| African Amer. | 1 (3.6%) | 16 (8.3%) | |

|

| |||

| Failed Tx | 1 (3.6%) | 13 (6.8%) | 0.5 |

|

| |||

| Maintenance Immunosuppression: | 0.4 | ||

| Mycophenolate+CNI*+Prednisone | 13 (46.4%) | 72 (37.5%)** | |

| Mycophenolate+CNI* | 14 (50%) | 117 (60.9%) | |

| Transition to Sirolimus | 5 (17.9%) | 38 (19.8%) | |

|

| |||

| DD/LRD/LURD | 17(61%)/5(18%)/6(21%) | 108(56%)/45(23%)/39(20%) | 0.8 |

|

| |||

| Post-transplant BKV viremia | 4 (14%) | 27 (29%) | 0.9 |

|

| |||

| Post-transplant BKV viruria | 12 (43%) | 26 (14%) | 0.004 |

CNI = Calcineurin Inhibitor

5 recipients got Azathioprine instead of MMF

Pre-Transplant Recipient BKV Shedding

There was no BK viremia in any recipients prior to transplant. BK virus was also not detectable in the oral specimens of any recipients prior to transplant. BK virus was detectable in the urine of 28 (16%) recipients prior to transplant (including 2 pediatric recipients) but urinary samples were unavailable in 48 recipients. Recipients with and without BK viruria were not significantly different except they were more often kidney recipients [Table 2]. Prevalence of BK viruria in recipients prior to transplant was not significantly different from prevalence of BK viruria in healthy donors (p = 0.1). Urinary BKV titers prior to transplant in recipients ranged from 900 to 1,514,900copies/ml (mean 119,032).

Impact of Pre-Transplant BKV Viruria on Post-transplant BKV Infection/Disease

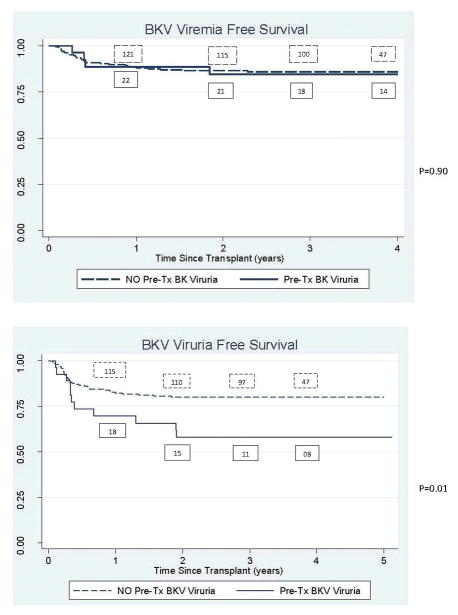

All recipients with pre-transplant BKV viruria had post-transplant viruria; significantly more than observed in recipients that did not have viruria prior to transplant (p <0.005). Both the pediatric recipients with pre-transplant BKV viruria had post-transplant viruria. Time to viruria was also significantly shorter in recipients shedding virus in the urine prior to transplant (p 0.01) [Figure 1]. Even on multivariate analysis, BKV viruria pre-transplant was significantly associated with post-transplant BKV viruria (p 0.008). However, by univariate and multivariate analysis, BKV viruria in recipients pre-transplant did not impact post-transplant BKV viremia (p=0.97 and 0.97 respectively). This observation was consistent when the analysis was stratified by type of organ transplant (kidney p=0.6; liver p=0.5). In fact, only 4 of the 31 recipients to develop post-transplant viremia had pre-transplant BKV viruria. One of the 2 pediatric recipients with pre-transplant viruria did have post-transplant BK viremia with BKV PCR 1500–6000 copies/mL but no evidence of BKV nephropathy. The patient did however develop hemorrhagic cystitis which resolved with immune-reduction. When recipients that did not have pre-transplant urinary specimens were excluded, the results remained unchanged.

FIGURE 1.

Survival curves for BK viremia and BK viruria stratified by whether the recipients had detectable BK viruria prior to transplant

The peak serum BKV PCR post-transplant was not significantly different in recipients with (mean +/− standard deviation 1,200+/−587copies/ml) and without (mean +/− standard deviation 13,780+/−9,104copies/ml) viruria pre-transplant (p=0.6). The peak urinary BK PCR post-transplant was not significantly different in recipients with (mean +/− standard deviation 1,445,089+/1,081,444 copies/ml) and without viruria (mean +/− standard deviation 855,480+/−525,338) pre-transplant (p=0.6).

None of the included cases developed BK nephropathy.

Discussion

In the largest prospective study of its kind, we demonstrated that pre-transplant BKV viruria was NOT associated with an increased incidence of post-transplant BKV viremia or BKV nephropathy. BKV related complications are of no less clinical relevance to children and yet, ours is the first study of its kind to include pediatric recipients.

We have previously demonstrated that BKV viremia after transplant is likely of donor origin and is impacted by donor viral replication in the urine prior to transplant (11). This study was done to assess whether active recipient BKV viruria prior to transplant could also play a role in BKV infection and disease development following immunosuppression and organ transplantation. Pre-transplant kidney recipient BKV viruria was independently and significantly associated with post-transplant recipient BKV viruria, but not viremia or BKV nephropathy. Time to viruria was also significantly shorter after transplant in recipients with BK viruria prior to the transplant. We acknowledge that our study does not allow identification of the source of post-transplant BKV in recipients – native kidneys vs. donor kidney, particularly, since the number of recipients that had native nephrectomies at or pre-transplant was small. Since only 32 (14.5%) patients had less than 1 year post-transplant follow up, and loss to follow up was patient death/graft loss in the majority, we believe it is unlikely that a differential biologic effect in the frequency of progression to BKV nephropathy was missed given that BKV nephropathy is largely recognized as an early event occurring within the first year after transplantation (16) (17). BKV viruria in the absence of BKV viremia is not usually associated with an increased risk for BKV disease (18), although in patients with BKV nephropathy, it is often preceded by viruria and then viremia (17). In our patients, viruria did not predict viremia or nephropathy. We conclude that despite the association of recipient BK viruria pre- and post-transplant, the urinary BKV likely represents asymptomatic shedding of no clinical significance. While we were unable to find an association between pre-transplant viruria and post-transplant viremia, it should be acknowledged that BKV viruria is a precursor to BKV viremia, which is a known precursor to BKV nephropathy. Our findings concur with a small 34 recipient study done in Sao Paolo, which demonstrated that pre-transplant BKV viruria had no impact on post-transplant BKV viremia. The Brazilian study only included adult kidney recipients and excluded recipients with death or graft loss. In their study, all recipients developed BKV viruria post-transplant and the prevalence of pre and post-transplant BKV viruria was higher than at our center or in other reports (14). This could reflect geographic differences in BKV strains, an observed phenomenon with this virus (19–23). Our findings are also supported by a small 32 recipient study done in North India (13). Contrary to our findings, in 2008, a study demonstrated an increased risk of post-transplant BKV infection with reactivation of latent BKV; however, the viruria testing in this study was done by detecting decoy cells (24), and therefore, their results cannot be compared to the PCR technique utilized in our study. In addition, none of these previous studies included children and the demographics were not comparable to the North American cohort.

Of the 28 children included in this study, only 2 (7%) had viruria prior to transplant, which is non-significantly less than observed in the 26 (13.5%) adult transplant recipients. This is in keeping with the known high BKV antibody prevalence in adult kidney donors (25, 26). Of the 2 children with viruria prior to transplant, 1 developed post-transplant hemorrhagic cystitis with transient viremia for 3 months and 1 had persistent viruria without viremia or clinical symptoms. The numbers are too small to make a clinically relevant conclusion from this observation.

BKV viruria was identified in 12% of organ recipients and 13% of kidney recipients prior to transplant. This was not significantly different from the prevalence of BKV viruria in healthy donors and is in keeping with other reports of rates of BK viruria in the healthy population (25, 27); therefore, detectable viral replication does not appear to be influenced by organ failure. None of our recipients or donors had detectable BKV in their blood prior to transplant. This contradicts an Italian study that demonstrated that some recipients with renal failure have BKV viremia with an increased risk of subsequent post-transplant BKV infection and disease (12). The differences in their results could be that they utilized a qualitative test to screen for BKV viremia, which cannot be compared to the quantitative PCR test utilized in this study; therefore, the significance of their results are difficult to interpret.

None of the included 220 recipients developed BKV nephropathy, and post-transplant viremia occurred in 14% of recipients, which is less than reported at most other centers (14, 28). Differences for the reduced rate of BKV nephropathy and post-transplant viremia at the University of Minnesota are unclear. Replication of BKV in recipients post-transplant had no significant impact on death-censored graft survival, recipient survival or viral disease free survival.

While the lack of BKV antibody data in our study is unfortunate, BKV antibody testing is not routinely done at most centers including ours. Another limitation is the lack of uniform immunosuppression; however, this allows for better generalizability of the conclusions of this paper. BKV typing to conclusively prove that the post-transplant BKV was recipient vs. donor origin was not done. Limitations include the small size of the pediatric cohort as well as the absence of the calculation of sample size prior to the start of the study.

In conclusion, BKV viruria did occur in adult and pediatric recipients awaiting organ transplantation at a similar rate as healthy donors, but BKV viremia was not confirmed in any recipients awaiting organ transplant. Detectable BKV viral replication, at or before transplant, did not predict post-transplant viremia or BKV nephropathy in kidney or other organ recipients.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by a grants from the National Institutes of Health (2PO1 DK13083), and the University of Minnesota International Center for Antiviral Research and Epidemiology and the University of Minnesota Foundation.

List of Abbreviations

- BKV

BK polyomavirus

- EDTA

Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid

- EIAs

Enzyme immunoassays

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP PAGE

Priya Verghese: Participated in research design, writing of the paper, performance of the research and data analysis

Arthur J. Matas: Participated in research design and performance of the research

David O. Schmeling: Participated in performance of the research

Emma A Filtz: Participated in performance of the research

Henry H. Balfour Jr: Participated in research design, writing of the paper, performance of the research and data analysis

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by Pediatric Transplantation.

References

- 1.Gardner SD, Field AM, Coleman DV, Hulme B. New human papovavirus (B.K.) isolated from urine after renal transplantation. Lancet. 1971 Jun 19;1(7712):1253–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91776-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah KV. Human polyomavirus BKV and renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000 Jun;15(6):754–5. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knowles WA. Discovery and epidemiology of the human polyomaviruses BK virus (BKV) and JC virus (JCV) Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2006;577:19–45. doi: 10.1007/0-387-32957-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verghese PS, Finn LS, Englund JA, Sanders JE, Hingorani SR. BK nephropathy in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Pediatric transplantation. 2009 Nov;13(7):913–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2008.01069.x. Epub 2008/12/11. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barton TD, Blumberg EA, Doyle A, Ahya VN, Ferrenberg JM, Brozena SC, et al. A prospective cross-sectional study of BK virus infection in non-renal solid organ transplant recipients with chronic renal dysfunction. Transpl Infect Dis. 2006 Jun;8(2):102–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2006.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Limaye AP, Smith KD, Cook L, Groom DA, Hunt NC, Jerome KR, et al. Polyomavirus nephropathy in native kidneys of non-renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2005 Mar;5(3):614–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2003.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ducharme-Smith A, Katz BZ, Bobrowski AE, Backer CL, Rychlik K, Pahl E. Prevalence of BK polyomavirus infection and association with renal dysfunction in pediatric heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015 Feb;34(2):222–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loeches B, Valerio M, Perez M, Banares R, Ledesma J, Fogeda M, et al. BK virus in liver transplant recipients: a prospective study. Transplantation proceedings. 2009 Apr;41(3):1033–7. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas LD, Vilchez RA, White ZS, Zanwar P, Milstone AP, Butel JS, et al. A prospective longitudinal study of polyomavirus shedding in lung-transplant recipients. J Infect Dis. 2007 Feb 1;195(3):442–9. doi: 10.1086/510625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loeches B, Valerio M, Palomo J, Bouza E, Munoz P. BK virus in heart transplant recipients: a prospective study. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011 Jan;30(1):109–11. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verghese PS, Schmeling DO, Knight JA, Matas AJ, Balfour HH., Jr The impact of donor viral replication at transplant on recipient infections posttransplant: a prospective study. Transplantation. 2015 Mar;99(3):602–8. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitterhofer AP, Tinti F, Pietropaolo V, Umbro I, Anzivino E, Bellizzi A, et al. Role of BK virus infection in end-stage renal disease patients waiting for kidney transplantation--viral replication dynamics from pre- to post-transplant. Clin Transplant. 2014 Mar;28(3):299–306. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thakur R, Arora S, Nada R, Minz M, Joshi K. Prospective monitoring of BK virus reactivation in renal transplant recipients in North India. Transpl Infect Dis. 2011 Dec;13(6):575–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bicalho CS, Oliveira RR, Pierrotti LC, Fink MC, Urbano PR, Nali LH, et al. Pretransplant shedding of BK virus in urine is unrelated to post-transplant viruria and viremia in kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2016 Apr 21; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmitt C, Raggub L, Linnenweber-Held S, Adams O, Schwarz A, Heim A. Donor origin of BKV replication after kidney transplantation. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2014 Feb;59(2):120–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dall A, Hariharan S. BK virus nephritis after renal transplantation. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2008 Mar;3( Suppl 2):S68–75. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02770707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuppachi S, Kaur D, Holanda DG, Thomas CP. BK polyoma virus infection and renal disease in non-renal solid organ transplantation. Clinical kidney journal. 2016 Apr;9(2):310–8. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirsch HH, Brennan DC, Drachenberg CB, Ginevri F, Gordon J, Limaye AP, et al. Polyomavirus-associated nephropathy in renal transplantation: interdisciplinary analyses and recommendations. Transplantation. 2005 May 27;79(10):1277–86. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000156165.83160.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mengel M, Marwedel M, Radermacher J, Eden G, Schwarz A, Haller H, et al. Incidence of polyomavirus-nephropathy in renal allografts: influence of modern immunosuppressive drugs. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003 Jun;18(6):1190–6. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li RM, Mannon RB, Kleiner D, Tsokos M, Bynum M, Kirk AD, et al. BK virus and SV40 co-infection in polyomavirus nephropathy. Transplantation. 2002 Dec 15;74(11):1497–504. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200212150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang YN, Han SM, Park KK, Jeon DS, Kim HC. BK virus infection in renal allograft recipients. Transplant Proc. 2003 Feb;35(1):275–7. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03954-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahamimov R, Lustig S, Tovar A, Yussim A, Bar-Nathan N, Shaharabani E, et al. BK polyoma virus nephropathy in kidney transplant recipient: the role of new immunosuppressive agents. Transplant Proc. 2003 Mar;35(2):604–5. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maiza H, Fontaniere B, Dijoud F, Pouteil-Noble C. Graft dysfunction and polyomavirus infection in renal allograft recipients. Transplant Proc. 2002 May;34(3):809–11. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)02919-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayat A, Mukhopadhyay R, Radhika S, Sachdeva MS, Nada R, Joshi K, et al. Adverse impact of pretransplant polyoma virus infection on renal allograft function. Nephrology (Carlton) 2008 Apr;13(2):157–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egli A, Infanti L, Dumoulin A, Buser A, Samaridis J, Stebler C, et al. Prevalence of polyomavirus BK and JC infection and replication in 400 healthy blood donors. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2009 Mar 15;199(6):837–46. doi: 10.1086/597126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knowles WA, Pipkin P, Andrews N, Vyse A, Minor P, Brown DW, et al. Population-based study of antibody to the human polyomaviruses BKV and JCV and the simian polyomavirus SV40. Journal of medical virology. 2003 Sep;71(1):115–23. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhong S, Zheng HY, Suzuki M, Chen Q, Ikegaya H, Aoki N, et al. Age-related urinary excretion of BK polyomavirus by nonimmunocompromised individuals. J Clin Microbiol. 2007 Jan;45(1):193–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01645-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirsch HH, Randhawa P Practice ASTIDCo. BK polyomavirus in solid organ transplantation. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2013 Mar;13( Suppl 4):179–88. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]